| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vivi Li | -- | 7849 | 2022-10-20 01:35:41 |

Video Upload Options

Islamist Shi'ism (Persian: تشیع اخوانی) is a denomination of Twelver Shia Islam greatly inspired by the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood ideologies and politicized version of Ibn Arabi's mysticism. It sees Islam as a political system and differs from the other mainstream Usuli and Akhbari groups in favoring the idea of formation of Islamist state in occultation of the twelfth Imam. Hadi Khosroshahi was the first person to identify himself as ikhwani (Islamist) Shia. Because of the concept of the hidden Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, Shia Islam is inherently secular in the age of occultation, so islamist Shi'ites had to borrow ideas from Sunni islamists and adjust them with Shi'i outlook. Islamism (Persian: اخوانی گری) (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern states and regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, economic and judicial terms, in accordance with what is conceived as a revival or a return to authentic Islamic practice in its totality. Ideologies dubbed Islamist may advocate a "revolutionary" strategy of Islamizing society through exercise of state power, or alternately a "reformist" strategy to re-Islamizing society through grassroots social and political activism. Islamists may emphasize the implementation of sharia, pan-Islamic political unity, the creation of Islamic states, or the outright removal of non-Muslim influences; particularly of Western or universal economic, military, political, social, or cultural nature in the Muslim world; that they believe to be incompatible with Islam and a form of Western neocolonialism. Some analysts such as Graham E. Fuller describe it as a form of identity politics, involving "support for (Muslim) identity, authenticity, broader regionalism, revivalism, (and) revitalization of the community." The term itself is not popular among many Islamists who believe it inherently implies violent tactics, human rights violations, and political extremism when used by Western mass media. Some authors prefer the term "Islamic activism", while Islamist political figures such as Rached Ghannouchi use the term "Islamic movement" rather than Islamism. Central and prominent figures in 20th-century Islamism include Sayyid Rashid Rida, Hassan al-Banna, Sayyid Qutb, Abul A'la Maududi, Hasan al-Turabi,and Ruhollah Khomeini.

1. Terminology

Islamism is a modern phenomenon but the term Islamism first appeared in the English language as Islamismus in 1696, and as Islamism in 1712, to describe the religion of Islam.[1] The term appears in the U.S. Supreme Court decision in In Re Ross (1891). By the turn of the twentieth century the shorter and purely Arabic term "Islam" had begun to displace it, and by 1938, when Orientalist scholars completed The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Islamism seems to have virtually disappeared from English usage.[2]

The term "Islamism" acquired its contemporary connotations in French academia in the late 1970s and early 1980s. From French, it began to migrate to the English language in the mid-1980s, and in recent years has largely displaced the term Islamic fundamentalism in academic circles.[2]

The new use of the term "Islamism" at first functioned as "a marker for scholars more likely to sympathize" with new Islamic movements; however, as the term gained popularity it became more specifically associated with political groups such as the Taliban or the Algerian Armed Islamic Group, as well as with highly publicized acts of violence.[2]

1.1. Definitions

Islamism has been defined as:

- "the belief that Islam should guide social and political as well as personal life",[3]

- a form of "religionized politics" and an instance of religious fundamentalism,[4]

- "the ideology that guides society as a whole and that [teaches] law must be in conformity with the Islamic sharia".[5]

2. History

2.1. Pre-Modern Background

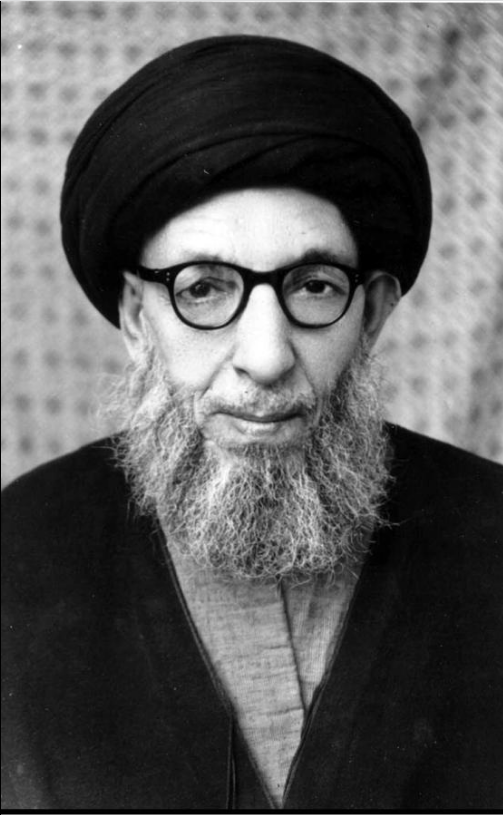

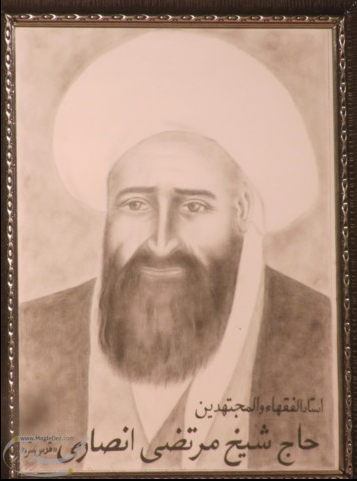

The idea that during the period of occultation of Imam Mahdi, clerics could rule as his deputies can be traced back to the 19th century Shia scholar Mullah Ahmad Naraqi (Persian: ملا احمد نراقی;1771 – 1829). His was a period of epic Usuli-Akhbari schism on one hand and the spread of Shaykhi Sufism on the other hand, which was based on Shaikh Ahmad Ahsai's neo-platonic ideas about the Perfect Shia. Naraqi's idea of jurist as the perfect leader was influenced by both debates.[6] He insisted on the absolute guardianship of the jurist over all aspects of a believer's personal life, but he did not claim jurist's authority on public affairs and did not present Islam as a modern nation-state system. He did not pose any challenge to Fath Ali Shah Qajar, and upon his order declared Jihad against Russia, which Iran lost.[6] Naraqi's most famous student, the great Shi'ite jurist Ayatullah Shaykh Murtaza Ansari, argued against the idea of jurist's absolute authority over all affairs of a believer's life.[6]

Around the same time in 1827, a Sunni cleric-cum-military commander Syed Ahmad Barelvi (Urdu: سيد احمد بن عرفان بریلوی; 1786–1831) established a religious emirate in Peshawar, now a metropolitan city in Pakistan . Born in Rae Bareli in 1786, Sayyid Ahmad received his religious education under Sunni polemicist Shah Abdul Aziz Dehlavi. He joined the militia of Amir Khan, a military expeditionary who only fought to loot and plunder, at the age of 25. In 1817, after the Third Anglo-Maratha War, Amir Khan received a large stipend from the British and disbanded his militia. Syed Ahmad, now unemployed, formed a Jihad movement and decided to become a power player.[7] Syed Ahmad had called upon Sunni muslims of North India to strictly abide by the tenets of the shariah (Islamic law) by following the Qur'an and the Sunnah. The most prominent feature of Sayyid Ahmad's teachings was his warning to avoid shirk (polytheism), bid'ah (religious innovations); and re-assertion of Tawhid (montheism).[8] Sayyid Ahmad visited numerous towns of Awadh, Bihar and Bengal between 1818 to 1821 and incited hundreds of missionaries to preach against Shia beliefs and practices. Syed Ahmad repeatedly destroyed tazias, an act that resulted in subsequent riots and chaos.[9] Sayyid Ahmad is reported to have organized burning of thousands of taziyas, replicas of shrines of Shia Imams.[10]

Arriving in Peshawar valley in late 1826, Syed Ahmad called upon the local Pashtun tribes to wage Jihad, and demanded that they renounce their tribal customs and adopt the Sharia (Islamic law). He sent an ultimatum to the ruler of Punjab, Ranjit Singh, demanding:

"either become a Muslim, pay Jizyah or fight and remember that in case of war, Yaghistan supports the Indians".[11]

Around 8,000 Mujahideen (holy-warriors) accompanied him, mostly consisting of clergymen and poor people. The mujahideen also chanted several Islamic anthems. One such popular anthem has survived, known as "Risala Jihad". It goes as follows:

"War against the Infidel is incumbent on all Musalmans;

make provisions for all things.

He who from his heart gives one farthing to the cause,

shall hereafter receive seven hundredfold from God.

He who shall equip a warrior in this cause of God,

shall hereafter obtain a martyr's reward;

His children dread not the trouble of the grave,

nor the last trump, not the Day of Judgement.

Cease to be crowded; join the divine leader, and smite the Infidel.

I give thanks to God that a great leader has been born,

in the thirteenth of the Hijra".[12]

Defending his claim to Caliphate, Sayyid Ahmad writes:

"We thank and praise God, the real master and the true king, who bestowed upon his humble, recluse and helpless servant the title of Caliphate, first through occult gestures and revelations, in which there is no room for doubt, and then by guiding the hearts of the believers towards me. This way God appointed me as the Imam (leader)... the person who sincerely confesses to my position is special in the eyes of God, and the one who denies it is, of course sinful. My opponents who deny me of this position will be humiliated and disgraced".[7]

Excommunicating the opponents of his Jihad movement as apostates and obliging all Muslims to fight them, Shah Ismail Dehlvi, the faithful disciple of Sayyid Ahmad, wrote:

"..obedience to Syed Ahmad is obligatory on all Muslims. Whoever does not accept the leadership of His Excellency or rejects it after accepting it, is an apostate and mischievous, and killing him is part of the jihad as is the killing of the disbelievers. Therefore, the appropriate response to opponents is that of the sword and not the pen".[7]

The decisive moments for Syed Ahmad came in 1830. The Pashtuns rose against him and around two hundred Mujahidin were killed in the Peshawar valley which compelled him to migrate and try his luck in Kashmir.[13] On 6 May 1831, on the day of Jumu'ah 23 Zulqa'da 1246 AH, Syed Ahmad Barelvi was killed at Balakot, under a joint Sikh-Muslim attack, after Pashtuns had made an alliance with Sikh Empire.[14]

2.2. A New Age

End of nineteenth century marked the end of the middle ages. New technological advances in printing press, telegraph and railways, etc., along with political reforms brought major social changes and the institution of nation-state started to take shape. Barbara Metcalf and Thomas Metcalf explain the new social life in India as:

The decades that spanned the turn of the twentieth century marked the apogee of the British imperial system, whose institutional framework had been set after 1857. At the same time, these decades were marked by a rich profusion and elaboration of voluntary organizations; a surge in publication of newspapers, pamphlets and posters; and the writing of fiction and poetry as well as political, philosophical, and historical non-fiction. With this activity, a new level of public life emerged, ranging from meetings and processions to politicized street theatre, riots, and terrorism. The vernacular languages, patronized by the government, took new shape as they were used for new purposes, and they became more sharply distinguished by the development of standardized norms. The new social solidarities forged by these activities, the institutional experience they provided, and the redefinitions of cultural values they embodied were all formative for the remainder of the colonial era, and beyond."[17]

Denis Hermann writes about how these changes affected the Shia world:

Akhund Khurasani was one of the first great mujtahids and marja'-i taqlid who, thanks to new technological advances such as the development of the telegraph and the expansion of the press, was able to address the Shi'ite masses regularly. In fact, it was partly thanks to the telegraph that Sayyid Muhammad Hasan Shirazi (d. 1312H/1894CE) had been able to mobilize the Iranian population against the tobacco concession so easily in 1890-91.[18]

2.3. First Democratic Revolution in Asia and Usuli-Islamist Controversy

Islamist Shi'ism started to take shape during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution when Sheikh Fazlullah Nouri (Persian: فضلالله نوری) a rich court official responsible for conducting marriages and contracts changed his political stance towards the revolution after coronation of Muhammad Ali Shah Qajar, who unlike his father Mozaffar al-Din Shah, opposed the idea of democratic reform and decided to use the religion card.[19] [20] Nuri was opposed to the very foundations of the institution of parliament. He lead a large group of followers and began a round-the-clock sit-in in the Shah Abdul Azim shrine on June 21, 1907, which lasted till September 16, 1907. He generalized the idea of religion as a complete code of social life to push for his own agenda. He believed democracy will allow for “teaching of chemistry, physics and foreign languages”, that would result in spread of Atheism.[21] [20] He bought a printing press and launched a newspaper of his own for propaganda purposes, “Ruznamih-i-Shaikh Fazlullah”, and published leaflets.[22] [20] He said:

Shari'a covers all regulations of government, and specifies all obligations and duties, so the needs of the people of Iran in matters of law are limited to the business of government, which, by reason of universal accidents, has become separated from Shari'a. . . .Now the people have thrown out the law of the Prophet and have set up their own law instead.[23]

Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi, the enlightened Thiqa tul-islam from Tabriz, wrote a treatise “Lalan”(Persian: لالان).[24] He opposed Nouri saying that only the opinion of the sources of emulation is worthy of consideration in the matters of faith.[25]

He wrote:

Let us consider the idea that the constitution is against Sharia law: all oppositions of this kind are in vain because the hujjaj al-islam of the atabat, who are today the models (marja') and the refuge (malija) of all Shiites, have issued clear fatwas that uphold the necessity of the Constitution. Aside from their words, they have also shown this by their actions. They see in Constitution the support for splendour of Islam.[24]

Nouri said that an imitator should not follow the jurist if he supports democracy:

If a thousand jurists write that this parliament is founded on the command to do good and prohibit evil . . . then you are witness that this is not the case and they have erred . . . (exactly as if they were to say) this animal is a sheep, and you know it is a dog, you have to say, 'You are mistaken, it is unclean'.[26]

Nouri believed that the King was accountable to no institution other than God and people have no right to limit the powers or question the conduct of the King. He declared that those who supported democratic form of government were faithless and corrupt, and apostates.[27] [28] He hated the idea of female education and said that girls schools were brothels.[29] Alongside his vicious propaganda against women education, he also opposed allocation of funds for modern industry, modern ways of governance, equal rights for all citizens irrespective of their religion and freedom of press. He believed that people were cattle, but paradoxically, he wanted to “awaken the muslim brethren”.[30]

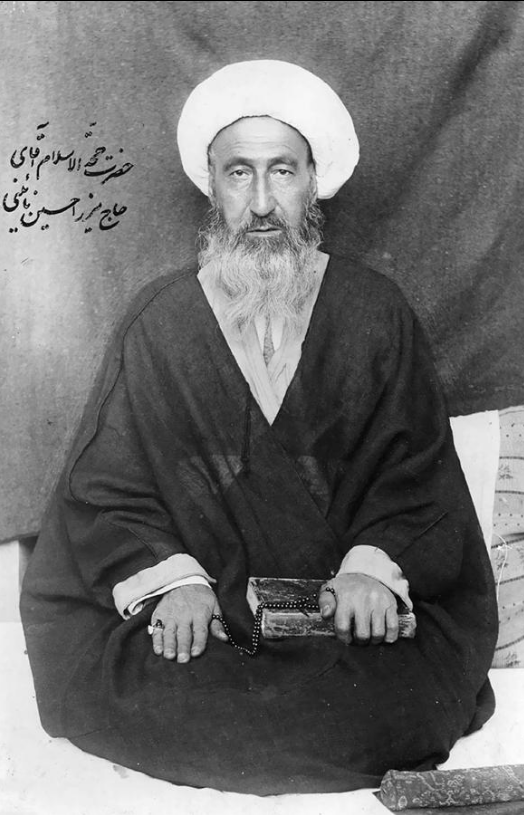

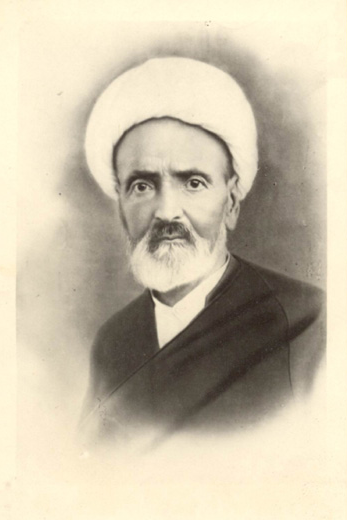

This attempt to present democracy as anti-Islam project failed because of the intervention of Usuli Marja's, Akhund Khurasani, Mirza Husayn Tehrani and Abdallah Mazandarani.[31] Akhund Khurasani was consulted on the matter by the parliament and in a letter dated December 30, 1907, the three Marja's said:[32]

Persian:چون نوری مخل آسائش و مفسد است، تصرفش در امور حرام است.

محمد حسین (نجل) میرزا خلیل، محمد کاظم خراسانی، عبدالله مازندرانی [33]

“Because Nuri is causing trouble and sedition, his interfering in any affair is forbidden.”

—Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

However, Nuri continued his activities and a few weeks later Akhund Khurasani and his fellow Marja's argued for his expulsion from Tehran:[34]

Persian:رفع اغتشاشات حادثه و تبعید نوری را عاجلاً اعلام.

الداعی محمد حسین نجل المرحوم میرزا خلیل، الداعی محمد کاظم الخراسانی، عبدالله المازندرانی [35]

“Restore peace and expel Nuri as quickly as possible.”

—Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

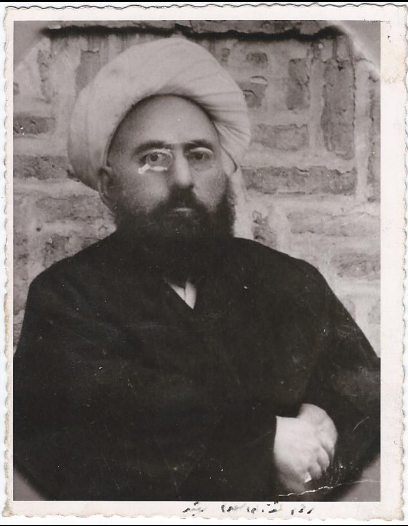

Like his mentor Ayatullah Murtaza Ansari, Akhund believed that a jurist was not different from ordinary people in the matters of politics, as Shia school of thought didn't allow for special political status of jurists. Rather, he believed that scholars could act as "warning voices in society" and criticize the officials who were not doing their responsibilities correctly.[36] When new technologies entered the Muslim world,[37] Akhund Khurasani as a pragmatic jurist supported the idea of nation-state as unity of people and government.(Persian: اتحاد دولت و ملت).[38][39] He believes that an Islamic system of governance can not be established without the infallible Imam leading it. Thus the clergy and modern scholars have concluded that a proper legislation can help reduce the state tyranny and maintain peace and security. He said:[40]

Persian: سلطنت مشروعه آن است کہ متصدی امور عامه ی ناس و رتق و فتق کارهای قاطبه ی مسلمین و فیصل کافه ی مهام به دست شخص معصوم و موید و منصوب و منصوص و مأمور مِن الله باشد مانند انبیاء و اولیاء و مثل خلافت امیرالمومنین و ایام ظهور و رجعت حضرت حجت، و اگر حاکم مطلق معصوم نباشد، آن سلطنت غیرمشروعه است، چنان کہ در زمان غیبت است و سلطنت غیرمشروعه دو قسم است، عادله، نظیر مشروطه کہ مباشر امور عامه، عقلا و متدینین باشند و ظالمه و جابره است، مثل آنکه حاکم مطلق یک نفر مطلق العنان خودسر باشد. البته به صریح حکم عقل و به فصیح منصوصات شرع «غیر مشروعه ی عادله» مقدم است بر «غیرمشروعه ی جابره». و به تجربه و تدقیقات صحیحه و غور رسی های شافیه مبرهن شده که نُه عشر تعدیات دوره ی استبداد در دوره ی مشروطیت کمتر میشود و دفع افسد و اقبح به فاسد و به قبیح واجب است.[41]

English: “According to Shia doctrine, only the infallible Imam has the right to govern, to run the affairs of the people, to solve the problems of the Muslim society and to make important decisions. As it was in the time of the prophets or in the time of the caliphate of the commander of the faithful, and as it will be in the time of the reappearance and return of Muhammad al-Mahdi. If the absolute guardianship is not with the infallible then it will be a non-islamic government. Since this is a time of occultation, there can be two types of non-islamic regimes: the first is a just democracy in which the affairs of the people are in the hands of faithful and educated men, and the second is a government of tyranny in which a dictator has absolute powers. Therefore, both in the eyes of the Sharia and reason what is just prevails over the unjust. From human experience and careful reflection it has become clear that democracy reduces the tyranny of state and it is obligatory to give precedence to the lesser evil.”

—Muhammad Kazim Khurasani

As “sanctioned by sacred law and religion”, Akhund believes, a theocratic government can only be formed by the infallible Imam.[42] Aqa Buzurg Tehrani also quoted Akhund Khurasani saying that if there was a possibility of establishment of a truly legitimate Islamic rule in any age, God must end occultation of the Imam of Age. Hence, he refuted the idea of absolute guardianship of jurist.[43] [44] Therefore, according to Akhund, Shia jurists must support the democratic reform. He prefers collective wisdom (Persian: عقل جمعی) over individual opinions, and limits the role of jurist to provide religious guidance in personal affairs of a believer.[45] He defines democracy as a system of governance that enforces a set of “limitations and conditions” on the head of state and government employees so that they work within “boundaries that the laws and religion of every nation determines”. Akhund believes that modern secular laws complement traditional religion. He asserts that both religious rulings and the laws outside the scope of religion confront “state despotism”.[46] Constitutionalism is based on the idea of defending the “nation’s inherent and natural liberties”, and as absolute power corrupts, a democratic distribution of power would make it possible for the nation to live up to its full potential.[47]

His close associate and student, who later rose to the rank of Marja, Muhammad Hussain Naini, wrote a book, “Tanbih al-Ummah wa Tanzih al-Milla”(Persian: تنبیه الامه و تنزیه المله), to counter the propaganda of Nuri group.[49] [42] [50] He devoted many pages to distinguish between tyrannical and democratic regimes. In democracies, power is distributed and limited through constitution.[42] He maintained that in the absence of Imam Mahdi, all governments are doomed to be imperfect and unjust, and therefore people had to prefer the bad over the worse. Hence, the constitutional democracy was the best option to help improve the condition of the society as compared to absolutism, and run the worldly affairs with consultation and better planning. he saw the elected members of the parliament as representatives of the people, not deputies of the Imam, hence they didn't need a religious justification for their authority. He said that both the “tyrannical Ulema” and the radical societies who promoted majoritarianism were a threat to both Islam and democracy. The people should avoid the destructive, corrupt and divisive forces and maintain national unity.[49][51] He devoted large section of his book to definition and condemnation of religious tyranny. He then went on to defend people's freedom of opinion and expression, equality of all citizens in eyes of the nation-state regardless of their religion, separation of the legislative, executive and judicial powers, accountability of the King, people's right to share power.[49] [52] Another student of Akhund who too raised to the rank of Marja, Shaykh Isma'il Mahallati, wrote a treatise “al-Liali al-Marbuta fi Wajub al-Mashruta”(Persian: اللئالی المربوطه فی وجوب المشروطه).[42] In his view, during the occultation of the twelfth Imam, the governments can either be imperfectly just or oppressive. Since it was duty of a believer to actively fight injustice, it was necessary to strengthen democratic process.[53] he insisted on the need for reforming the economic system, modernizing the military, installing a functional education system, and guaranteeing the rights of civilians.[53] He said:

‘constitutional’ and ‘oppressive’ are both only adjectives that describe different governments. If the sovereign appropriates all power to himself, for his own personal benefit, then the government is a tyrannical one; if, on the other hand, the sovereign’s power is limited by the people, then the government is constitutional. This distinction has nothing to do with religion. Whatever the religion of the inhabitants of a nation, whether they be monotheistic or polytheistic, Muslims or unbelievers, their government could be either constitutional or tyrannical.[45]

Nuri interpreted Sharia in a self-serving and shallow way, unlike Akhund Khurasani who, as a well received source of emulation, viewed the adherence to religion in a society beyond one person or one interpretation.[54] While Nuri confused Sharia with written constitution of a modern society, Akhund Khurasani understood the difference and the function of the two.[55] Nuri founded his arguments on myths and reached illogical conclusion. He had a narrow understanding of modernity and had no alternative to offer.[56] He perceived the new social contract as a threat to his own prestige and lavish lifestyle.[57] Fazlullah Nouri was hanged by the constitutional revolutionaries on 31 July 1909 (in Toopkhaneh) as a traitor, for playing pivotal role in coup d'état of Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar in 1908. The Shah had fled to Russia. Syed Abdullah Behbahani, a pro-democracy Shi'a jurist, member of Parliament and close associate of Akhund Khurasani. On Friday 15 July 1910, four gunmen associated with the communist leader Haydar Khan Amo-oghli entered his home and killed him.[58]

2.4. Debate on Revival of Caliphate

The abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on 1 November 1922 ended the Ottoman Empire, which had lasted since 1299. On 11 November 1922, at the Conference of Lausanne, the sovereignty of the Grand National Assembly exercised by the Government in Angora (now Ankara) over Turkey was recognized. The last sultan, Mehmed VI, departed the Ottoman capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul), on 17 November 1922. The legal position was solidified with the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1923. In March 1924, the Caliphate was abolished, marking the end of Ottoman influence. This shocked the Sunni clerical world, and some felt the need to present Islam not as a traditional religion but as an innovative socio-political ideology of a modern nation-state.[59] The success of the October Revolution, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin in 1917 was a source of inspiration.[60][61] In British India, the Khilafat movement (1919–24) following World War I was led by Shaukat Ali, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Abul Kalam Azad as a expression of this desperation. The reaction to new realities of the modern world gave birth to Islamist ideologues like Rashid Rida and Abul A'la Maududi and organizations such as Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam in India. Rashid Rida was a prominent Salafi theologian of Egypt who called for the revival of Hadith studies in Sunni seminaries and a pioneering theoretician of Islamism in the modern age.[62] During 1922–1923, Rida would publish a series of articles in Al-Manar titled “The Caliphate or the Supreme Imamate”. In this highly influential treatise, Rida advocates for the restoration of Caliphate ruled by muslim jurists and proposes gradualist measures of education, reformation and purification through the efforts of Salafiyya reform movements across the globe.[63] Ayatullah Khomeini's book government of the jurist is greatly influenced by this book, so is his call to the pure Islam (Persian: اسلام ناب) and his analysis of the post-colonial Muslim world.[64] Sayyid Rashid Rida, a student of Muhammad Abduh, had visited India in 1912 and was impressed by the Deoband and Nadwatul Ulama seminaries.[65] These seminaries carried the legacy of Syed Ahmad Barelvi and his pre-modern Islamic emirate.[66] Maududi was an Islamist ideologue and Hanafi Sunni scholar active in Hyderabad Deccan and later in Pakistan . Maududi was born to a clerical family and got his early education at home. At the age of eleven, he was admitted to a public school in Aurangabad. In 1919, he joined the Khilafat Movement and got closer to the scholars of Deoband.[67] He commenced the dars-i nizami education under supervision of Deobandi seminary at the Fatihpuri mosque in Delhi.[59] In 1925, he wrote a book on Jihad, al-Jihad fil-Islam(Arabic: الجهاد في الاسلام), that can be regarded as his first contribution to islamism.[68] He was a prolific writer and wrote many books.[69] His writings had a profound impact on Sayyid Qutb.[70]

2.5. Fada'ian-e Islam

Sayyid Mojtaba Mir-Lohi (Persian: سيد مجتبی میرلوحی, c. 1924 – 18 January 1956), more commonly known as Navvab Safavi (Persian: نواب صفوی), emerged on political scene. He was born in Tehran in 1924 and raised by his maternal uncle who sent him to public schools for elementary education and then to the German Technical High School in Tehran. He found a job as a metalworker in Abadan in 1943, but the next year left for Najaf to get religious education in the Hawza. In 1945, after two years of study, he left the seminaries and returned to Tehran.[71]}} He founded the Fada'iyan-e Islam terror group by recruiting the frustrated youth from suburbs of Tehran. In a 1945 declaration, he said:

We are alive and God, the revengeful, is alert. The blood of the destitute has long been dripping from the fingers of the selfish pleasure seekers, who are hiding, each with a different name and in a different colour, behind black curtains of oppression, thievery and crime. Once in a while the divine retribution puts them in their place, but the rest of them do not learn a lesson . . . Damn you! You traitors, imposters, oppressors! You deceitful hypocrites! We are free, noble and alert. We are knowledgeable, believers in God and fearless.[72]

Under the Pahlavi regime, the Usuli idea of democracy was suppressed and Shi'i Islamism found the space for revival. In 1950, at 26 years of age, he presented his idea of an Islamic State in a treatise, Barnameh-ye Inqalabi-ye Fada'ian-i Islam, which reflects his simplistic and naïve understanding of politics, history and society.[73] After the 1953 coup against Iran's prime minister Muhammad Musaddiq,[74] Navvab Safavi congratulated the Shah and said:

The country was saved by Islam and with the power of faith . . . The Shah and prime minister and ministers have to be believers in and promoters of, shi'ism, and the laws that are in opposition to the divine laws of God . . . must be nullified . . . The intoxicants, the shameful exposure and carelessness of women, and sexually provocative music . . . must be done away with and the superior teachings of Islam . . . must replace them. With the implementation of Islam's superior economic plan, the deprivation of the Muslim people of Iran, and the dangerous class difference would end.[75]

In the years to follow, he enjoyed a close association with the government. In 1954, he attended the Islamic Conference in Jordan and traveled to Egypt. There he learned about Hasan al-Banna, the founder of Muslim Brotherhood (Arabic: الإخوان المسلمين), who was killed by Egyptian government in 1949, and met Sayyid Qutb.[76] [77] The Shia Marja, Ayatullah Hossein Borujerdi, rejected the ideas of Navvab Safavi and his radical group. He questioned him about the robberies that his organization committed on gun point, Safavi replied:

Fada'ian-e Islam launched a campaign of character assassination against the Marja and called for excommunication of Borujerdi and the defrocking of religious scholars who opposed Shi'i Islamism, a practice realized after establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran for Ayatullah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari and other clerics through Special Clerical Court.[80] Navvab safavi didn't like Broujerdi's idea of Shia-Sunni rapprochement (Persian: تقریب), he advocated Shia-Sunni unification (Persian: وحدت) under Islamist agenda.[81] Fada'ian-e Islam carried out assassinations of Abdolhossein Hazhir, Haj Ali Razmara and Ahmad Kasravi. On 22 November 1955, after an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Hosein Ala', Navvab Safavi was arrested and sentenced to death on 25 December 1955 under terrorism charges, along with three other comrades, by the same military court that ordered the execution of communists.[76] The organization dispersed but after the death of Ayatullah Borujerdi, the Fada'ian-e Islam sympathizers found a new leader in Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini who appeared on political horizon through the June 1963 riots in Qom.[82] In 1965, prime minister Hassan Ali Mansur was assassinated by the group.[83]

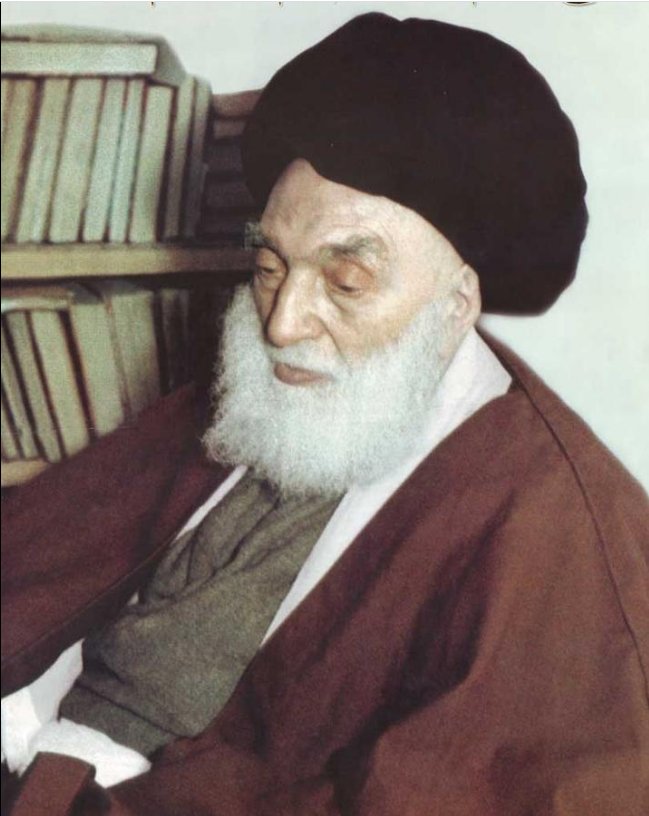

Ruhollah Khomeini, an ambitious cleric, used to deliver public speeches on gnosis and moral steadfastness. He had studied Ibn Arabi's gnosis and Mulla Sadra's theosophy, and taught and wrote books on it.[84] His keen interest in Plato's ideas, especially those of a Utopian society, had an impact on his political thought as well.[85] Khomeini also saw Fazlollah Nuri, the imperial court's cleric sentenced to death during Iran's constitutional revolution, as a "heroic figure", and his own objections to constitutionalism and a secular government derived from Nuri's objections to the 1907 constitution.[86][87][88] However the clergy in Qom didn't support the teaching of mysticism, and some even considered Khomeini impure. He reflected on it later in life:

They considered my son religiously impure simply because I was teaching theosophy and mysticism. [89]

2.6. Cold War Literature

Iran was undergoing a fast societal change through urbanization. In 1925 Iran was a thinly populated country with a population of 12 millions, 21% living in urban centers and Tehran was a walled city of 200,000 inhabitants. Pahlavi dynasty started major projects of converting the capital into a metropolis.[90] Between 1956 and 1966, the rapid industrialization coupled with land reforms and improved health systems, building of dams and roads, released some three million peasants from countryside into the cities.[91] This resulted in rapid changes in their lives, decline of traditional feudal values, and industrialization, changing the socio-political atmosphere and created new questions.[92] By 1976, 47% of Iran's total population was concentrated in large cities. Between 42 to 50 % of the population of Tehran lived on rent, 10% owned private car and 82.7% of all national companies were registered in the Capital.[93] Rapid urbanization in Iran had created a middle class and some writers started to critricize traditional interpretations of religion. In one of his first books, Kashf al-Asrar, Khomeini argued that liberal critics and writers were stupid and treacherous and believers must ‘smash in the teeth of this brainless lot with their iron fist’ and ‘trample upon their heads with courageous strides’.[94] He said:

Government can only be legitimate when it accepts the rule of God and the rule of God means the implementation of the Sharia. All laws that are contrary to the Sharia must be dropped because only the law of God will stay valid and immutable in the face of changing times. [94]

During the cold war, a massive translation of Muslim Brotherhood thinkers started in Iran. The books of Sayyid Qutb and Abul A'la Al-Maududi were promoted through Muslim World League by Saudi patronage to confront communist propaganda in the Muslim world.[95] The Shah regime in Iran tolerated the Muslim Brotherhood literature because not only it weakened the democratic Usulis but also, being in western camp, Shah understood that this was the main ideological response of West to penetrating Soviet communism in Muslim world.[96] Soviet reports of the time indicate that Persian translations of this literature were smuggled to Afghanistan too, where western block intended to use Islamists against the communists.[97] Khaled Abou el-Fadl thinks that Sayyid Qutb was inspired by the German fascist Carl Schmidt.[98] He embodied a mixture of Wahhabism and Fascism and alongside Maududi, theorized the ideology of Islamism. The writings of Maududi and other Pakistani and Indian Islamists were translated into Persian and alongside the literature of Muslim Brotherhood, shaped the ideology of Shi'i Islamists.[80] [99] Maududi appreciated the power of modern state and its coercive potential that could be used for moral policing. He saw Islam as a nation-state that sought to mould its citizens and control every private and public expression of their lives, like fascists and communist states.[100] Iranian Shi'i Islamists had close links with Maududi's Jamaat-e-Islami, and after the 1963 riots in Qom, the Jamaat's periodical Tarjuman ul-Quran published a piece criticizing the Shah and supporting the Islamist currents in Iran.[101] Sayyid Qutb's works were translated by Iranian Islamists into Persian and enjoyed remarkable popularity both before and after the revolution. Prominent figures such as current Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his brother Muhammad Khamenei, Aḥmad Aram, Hadi Khosroshahi, etc. translated Qutb's works into Persian.[102][103] Hadi Khosroshahi was the first person to identify himself as Akhwani Shia.[104] Muhammad Khamenei is currently head of Sadra Islamic Philosophy Research Institute, and holds positions at Al-Zahra University and Allameh Tabataba'i University.[105] According to the National Library and Archives of Iran, 19 works of Sayyid Qutb and 17 works of his brother Muhammad Qutb were translated to Persian and widely circulated in 1960's.[106] Reflecting on this import of ideas, Ali Khamenei said:

The newly emerged Islamic movement . . . had a pressing need for codified ideological foundations . . . Most writings on Islam at the time lacked any direct discussions of the ongoing struggles of the Muslim people . . . Few individuals who fought in the fiercest skirmishes of that battlefield made up their minds to compensate for this deficiency . . . This text was translated with this goal in mind. [107]

In 1952, Qutb had coined the term “American Islam”, he said:

The Islam that America and its allies desire in the Middle East does not resist colonialism and tyranny, but rather resists Communism only. They do not want Islam to govern and can not abide it to rule because when Islam governs, it will raise a different breed of humans and will teach people that it is their duty to develop their power and expel the colonialists . . . American Islam is consulted on the issued of birth control, the entry of women into Parliament, and on matters that impair ritual ablutions. However, it is jot consulted on the matter of our social and economic affairs and fiscal system, nor is it consulted on political and national affairs and our connections with colonialism.[108]

This term was adapted by Ayatullah Khomeini after the Islamist revolution in Iran.[109] In 1984 the Iranian authorities honoured Sayyid Qutb by issuing a postage stamp showing him behind the bars during trial.[110]

But Ayatullah Hadi Milani, the influential Usuli Marja in Mashhad during the 1970's, had issued a fatwa prohibiting his followers from reading Ali Shariati's books and islamist literature produced by young clerics. This fatwa was followed by similar fatwas from Ayatullah Mar'ashi Najafi, Ayatullah Muhammad Rouhani, Ayatullah Hasan Qomi and others. Ayatullah Khomeini refused to comment.[111] Ali Shariati, a bitter critic of traditional Usuli clergy, was also greatly influenced by anti-democratic Islamist ideas of Muslim Brotherhood thinkers in Egypt and he tried to meet Muhammad Qutb while visiting Saudi Arabia in 1969.[112] Shariati criticized Ayatullah Hadi al-Milani and other Usuli Marja's for not being revolutionary.[113] A chain smoker, Shariati died of a heart attack while in self-imposed exile in Southampton, on June 18, 1977.[114]

Meanwhile in Iraq, the Sunni dynasty of Hashemites founded by the British colonialism in 1921 fell after a successful military coup in 1958, led by the pro-soviet General Abd al-Karim Qasim. The religious learning centers came under immense pressure from the communist propaganda and government's attempts to curb religion as an obstacle to modernity and progress. Ayatollah Mohsin al-Hakim issued fatwa against communism.[115] Meanwhile a young cleric, Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr started to produce islamist literature and wrote books like Our Philosophy and Our Economy, and with some colleagues established the Islamic Dawa Party, with similar goals to that of Muslim Brotherhood, but left it after two years to focus on writing. Ayatullah Mohsin al-Hakim disapproved of his activities and ideas.[116] Qasim was overthrown on 8 February 1963, by a coalition of Ba'athists, army units, and other pan-Arabist groups. Abdul Salam Arif had previously been selected as the leader of the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council and after the coup he was elected president of Iraq. In 1968, the Ba'ath Party gained power after a coup of 1968, later called the 17 July Revolution. In the coup's aftermath, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr was elected the chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council and the president. Saddam Hussein, the Ba'ath Party's deputy, became the deputy chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council and vice president, and was responsible for Iraq's security services. The party started crackdown on Shi'i religious centers, closing periodicals and seminaries, expelling non-Iraqi students from Najaf. Ayatullah Mohsin al-Hakim called Shias to protest. This helped Baqir al-Sadr's rise to prominence as he visited Lebanon and sent telegrams to different international figures, including Abul A'la Maududi.[117]

2.7. Usuli-Islamist Clash in 1970's

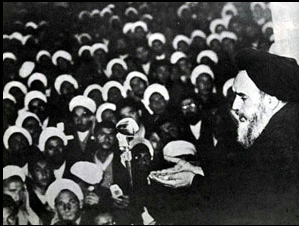

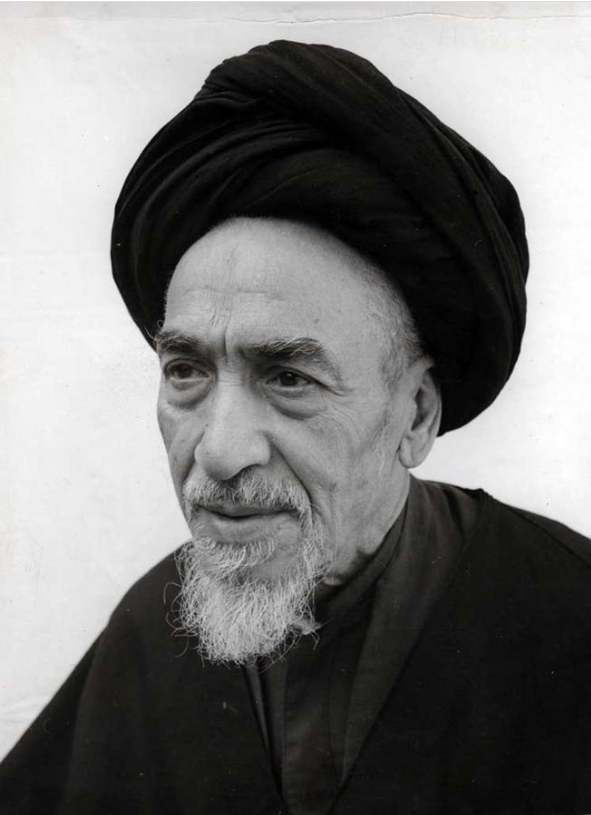

After his arrest in Iran following the 1963 riots, leading Ayatullahs had issued a statement that Ayatullah Khomeini was a legitimate Marja too, which saved his life and he was exiled.[118] While in exile in Iraq in the holy city of Najaf, Khomeini took advantage of the Iraq-Iran conflict and launched a campaign against the Pahlavi regime in Iran. Saddam Hussein gave him access to the Persian broadcast of Radio Baghdad to address Iranians and made it easier for him to receive visitors.[119] He gave a series of 19 lectures to a group of his students from January 21 to February 8, 1970, on Islamic Government, and elevated Naraqi's idea of Jurist's absolute authority over imitator's personal life to all aspects of social life. Notes of the lectures were soon made into a book that appeared under three different titles: The Islamic Government, Authority of the Jurist, and A Letter from Imam Musavi Kashef al-Gita[120] (to deceive Iranian censors). Khomeini The small book (fewer than 150 pages) was smuggled into Iran and "widely distributed" to Khomeini supporters before the revolution.[121] The response from high-level Shi'a clerics to his idea of absolute guardianship of jurist was negative. Grand Ayatollah Abul-Qassim Khoei, the leading Shia ayatollah at the time the book was published rejected Khomeini's argument on the grounds that the authority of jurist is limited to the guardianship of orphans and social welfare and could not be extended to the political sphere.[122] Al-Khoei elaborates on the role of a well-qualified Shia Jurist in the age of occultation of the Infallible Imam, which has been traditionally endorsed by the Usuli Shia scholars, as follows:

Arabic:أما الولاية على الأمور الحسبية كحفظ أموال الغائب واليتيم إذا لم يكن من يتصدى لحفظها كالولي أو نحوه، فهي ثابتة للفقيه الجامع للشرائط وكذا الموقوفات التي ليس لها متولي من قبل الواقف والمرافعات، فإن فصل الخصومة فيها بيد الفقيه وأمثال ذلك، وأما الزائد على ذلك فالمشهور بين الفقهاء على عدم الثبوت، والله العالم[123]

English: “As for wilayah (guardianship) of omour al-hesbiah (non-litigious affairs) such as the maintenance of properties of the missing and the orphans, if they are not addressed to preservation by a wali (guardian) or so, it is proven for the faqih jame'a li-sharaet and likewise waqf properties that do not have a mutawalli (trustee) on behalf of waqif (donor of waqf) and continuance pleadings, the judgement regarding litigation is in his hand and similar authorities, but with regards to the excess of that (guardianship) the most popular (opinion) among the jurists is on absence of its evidence, Allah knows best.”

Ayatullah Khoei showed great flexibility and tolerance, for example he considered non-Muslims as equal citizens of the nation-state, stopped the harsh punishments like stoning and favored the use of holy books other than Quran for oaths taken from non-Muslims.[124] In Isfahan, Ayatullah Khoei's representative Syed Abul Hasan Shamsabadi gave sermons criticizing the Islamist interpretation of Shi'i theology, he was abducted and killed by the notorious group called Target Killers (Persian: هدفی ها) headed by Mehdi Hashmi.[125][126] At Qom, the major Marja Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari was at odds with Khomeini's interpretation of the concept of the "Leadership of Jurists" (Wilayat al-faqih), according to which clerics may assume political leadership if the current government is found to rule against the interests of the public. Contrary to Khomeini, Shariatmadari adhered to the traditional Twelver Shiite view, according to which the clergy ought to serve society and remain aloof from politics. Furthermore, Shariatmadari strongly believed that no system of government can be coerced upon a people, no matter how morally correct it may be. Instead, people need to be able to freely elect a government. He believed a democratic government where the people administer their own affairs is perfectly compatible with the correct interpretation of the Leadership of the Jurists.[127] Before the revolution, Shariatmadari wanted a return to the system of constitutional monarchy that was enacted in the Iranian Constitution of 1906.[128] He encouraged peaceful demonstrations to avoid bloodshed.[129] According to such a system, the Shah's power was limited and the ruling of the country was mostly in the hands of the people through a parliamentary system. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the then Shah of Iran, and his allies, however, took the pacifism of clerics such as Shariatmadari as a sign of weakness. The Shah's government declared a ban on Muharram commemorations hoping to stop revolutionary protests. After a series of severe crack downs on the people and the clerics and the killing and arrest of many, Shariatmadari criticized the Shah's government and declared it non-Islamic, tacitly giving support to the revolution hoping that a democracy would be established in Iran.[130]

Meanwhile in Iraq, since 1972, The Ba'ath regime in Iraq had started arresting and killing members of the Dawa party. Ayatullah Khoei, Baqir al-Sadr and Khomeini condemned the act. Sadr issued a fatwa forbidding students of religious schools and clerics from joining any political party. In 1977, the Iraqi government banned the annual Azadari commemorations in Karbala.[131]

2.8. The 1979 Islamist Revolution

In 1977, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi appointed Jamshid Amouzegar as the new prime minister. Little did people know that the Shah was suffering from cancer and he wanted a younger, more energetic prime minister to run the affairs of the state. On 6 January 1978, an article appeared in the daily Ettela'at newspaper, insulting Ayatullah Khomeini. Frustrated youth in Qom took to the streets, six were killed. On 40th day of deaths in Qom, Tabriz saw uprising and death. The chain-reaction started and led to uprisings in all cities. Seizing the moment, Khomeini gave an interview to the French newspaper Le Monde and demanded that the regime should be overthrown. He started giving interviews to western media in which he appeared as a changed man, spoke of a ‘progressive islam’ and did not mention the idea of ‘guardianship of the jurist’. On 10th and 11th of December 1978, the days of Tasu'a and Ashura, millions marched on the streets of Tehran, chanting ‘Death to Shah’. On 16 Januray 1979, Shah fled the country.[132] After the success of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the major Iranian Usuli Marja Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari criticized Khomeini's system of government as not being compatible with Islam or representing the will of the Iranian people. He severely criticized the way in which a referendum was conducted to establish Khomeini's system of government. In response, Khomeini put him under house arrest and imprison his family members. This resulted in mass protests in Tabriz which were quashed toward the end of January 1980, when under the orders of Khomeini tanks and the army moved into the city.[133] Murtaza Mutahhari was a moderate islamist and believed that a jurist only had a supervisory role and was not supposed to govern.[134][135] In a 1978 treatise on modern Islamic movements, he warned against the ideas of Qutb brothers and Iqbal.[136] Soon after the 1979 revolution, he was killed by a rival group, Furqan, in Tehran.

Shortly after assuming power, Khomeini began calling for Islamic revolutions across the Muslim world, including Iran's Arab neighbor Iraq,[137] the one large state besides Iran with a Shia majority population. At the same time Saddam Hussein, Iraq's secular Arab nationalist Ba'athist leader, was eager to take advantage of Iran's weakened military and (what he assumed was) revolutionary chaos, and in particular to occupy Iran's adjacent oil-rich province of Khuzestan, and to undermine Iranian Islamic revolutionary attempts to incite the Shi'a majority of his country.

While Khomeini was in Paris, Baqir al-Sadr in Iraq issued a long statement to the Iranians praising their uprising. After the 1979 revolution, he sent his students to Iran to show support and called on Arabs to support the newly born Islamist state. He published a collection of six essays titled al-Islam Yaqud al-Hayat (Islam Governs Life), and declared that joining Ba'ath party was prohibited.[119] Khomeini responding by issuing public statements supporting his cause, that resulted in an uprising in Iraq. Sadr told his followers to call off demonstrations as he sensed the Sunni dominated Ba'ath party's preparations for a crackdown. The crackdown began by his arrest, in response to which the demonstrations spread nation-wide and the government had to release him the next day. The Ba'athists started to arrest and execute the second layer of leadership and killed 258 members of the Dawa party.[138] Dawa party responded by violence and threw a bomb at Tariq Aziz, killing his bodyguards.[139]

Saddam Hussain had become the fifth president of Iraq in 16 July 1979, and after publicly killing 22 members of Ba'ath party during the televised 1979 Ba'ath Party Purge, established firm control over the government.[140] Those spared were given weapons and directed to execute their comrades.[141][142] On 31 March 1980, the government passed a law sentencing all present and past members of the Dawa party to death. Sadr called on people to uprising. He and his vocal sister were arrested on 5 April 1980 and killed three days later.[139]

In September 1980, Iraq launched a full-scale invasion of Iran, beginning the Iran–Iraq War (September 1980 – August 1988). A combination of fierce resistance by Iranians and military incompetence by Iraqi forces soon stalled the Iraqi advance and, despite Saddam's internationally condemned use of poison gas, Iran had by early 1982 regained almost all of the territory lost to the invasion. The invasion rallied Iranians behind the new regime, enhancing Khomeini's stature and allowing him to consolidate and stabilize his leadership. After this reversal, Khomeini refused an Iraqi offer of a truce, instead demanding reparations and the toppling of Saddam Hussein from power.[143][144][145]

References

- "Islamism, n.". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/99982.

- Coming to Terms, Fundamentalists or Islamists? Martin Kramer originally in Middle East Quarterly (Spring 2003), pp. 65–77. http://www.meforum.org/541/coming-to-terms-fundamentalists-or-islamists

- Berman, Sheri (2003). "Islamism, Revolution, and Civil Society". Perspectives on Politics 1 (2): 258. doi:10.1017/S1537592703000197. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS1537592703000197

- Bassam Tibi (2012). Islamism and Islam. Yale University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0300160147. https://books.google.com/books?id=HyEyLXcIXgUC&pg=PA22.

- Shepard, W. E. Sayyid Qutb and Islamic Activism: A Translation and Critical Analysis of Social Justice in Islam. Leiden, New York: E.J. Brill. (1996). p. 40

- Mangol 1991, p. 13.

- Dr. Mubarak Ali, "Almiyah-e-Tarikh", Chapter 11, pp.107-121, Fiction House, Lahore (2012). https://todayspointonline.com/syed-ahmed-barelvi-and-his-jihad-movement/

- Hedayetullah, Muhammad (1968). Sayyid Ahmad: a Study of the Religious Reform Movement of Sayyid Ahmad of Ra'e Bareli. Montreal, Canada: Mcgill University. pp. 113, 115, 134. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/hq37vs57f.

- Andreas Rieck, "The Shia's of Pakistan", p. 16, Oxford University Press (2016).

- B. Metcalf, "Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860–1900", p. 58, Princeton University Press (1982). "A second group of abuses Syed Ahmad held were those that originated from Shi’i influence. He particularly urged Muslims to give up the keeping of ta’ziyahs. [...] Sayyid Ahmad himself is said, no doubt with considerable exaggeration, to have torn down thousands of imambaras, the building that house the taziyahs".

- Altaf Qadir, "Sayyid Ahmad Barailvi", p. 63, SAGE, London (2015).

- Charles Allen, "God's Terrorists: The Wahhabi Cult and the Hidden Roots of Modern Jihad", p. 86, Abacus (2006).

- Qadir, Altaf, "Sayyid Ahmad Barailvi: His Movement and Legacy from the Pukhtun Perspective, Sage Publications India, 2015| http://www.sagepub.in/books/Book244992?siteId=sage-india&prodTypes=any&q=Sayyid+Ahmad+Barailvi&pageTitle=productsSearch

- Altaf Qadir, "Sayyid Ahmad Barailvi", p. 150, SAGE, London (2015).

- Esposito, John,The Oxford Dictionary of Islam,(2003) p. 21

- Pāyā, ʻAlī; Esposito, John L. (2011) (in en). Iraq, Democracy and the Future of the Muslim World. Taylor & Francis. pp. 69. ISBN 978-0-415-58228-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=-eUf-NrqIqcC&pg=PA69.

- B. D. Metcalf and T. R. Metcalf, "A Concise History of Modern India", p. 123, Cambridge (2012). https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/concise-history-of-modern-india/civil-society-colonial-constraints-18851919/96A7AE049281D89791BCFF1E798AF2A9

- Hermann 2013, pp. 430, 431.

- Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=IQci1YIffjYC&pg=PA48

- Martin 1986, p. 182.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 196.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 197.

- Martin 1986, p. 183.

- Hermann 2013, p. 439.

- Hermann 2013, p. 438.

- Martin 1986, p. 191.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 198.

- Martin 1986, p. 185.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 199.

- Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=IQci1YIffjYC&pg=PA51

- Mangol 1991, pp. 181, 232.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 212.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص۱۷۷، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- Hermann 2013, p. 437.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص١٨٠، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 143.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 131.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 156.

- Kadivar 2008, pp. 159, 160.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 162.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص ۲۱۴-۲۱۵، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء https://kadivar.com/1253/

- Hermann 2013, p. 434.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 220.

- آخوند خراسانی، حاشیة المکاسب، ص 92 تا 96، وزارت ثقافت وارشاد اسلامی، تہران، ۱۴۰۶ ہجری قمری https://lib.eshia.ir/13025/1/92

- Hermann 2013, p. 436.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 166.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 167.

- Hermann 2013, p. 440.

- Nouraie 1975.

- Mangol 1991, p. 256.

- Mangol 1991, p. 257.

- Mangol 1991, p. 258.

- Hermann 2013, pp. 435.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 200.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 201.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 204.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 205.

- Sheikholeslami, Alireza. "ḤAYDAR KHAN ʿAMU-OḠLI". iranicaonline. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/haydar-khan-amu-ogli. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Rahnema 2005, p. 101.

- Rahnema 2005, p. x1vi.

- Kamran, Tahir (2013-10-01). "Majlis-i-Ahrar-i-Islam: religion, socialism and agitation in action". South Asian History and Culture 4 (4): 465–482. doi:10.1080/19472498.2013.824678. ISSN 1947-2498. https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2013.824678.

- Olidort, Jacob (2015). "A New Curriculum: Rashīd Riḍā and Traditionalist Salafism". In Defense of Tradition: Muḥammad Nāșir AL-Dīn Al-Albānī and the Salafī Method. Princeton, NJ, U.S.A: Princeton University. pp. 52–62. ""Rashīd Riḍā presented these core ideas of Traditionalist Salafism, especially the purported interest in ḥadīth of the early generations of Muslims, as a remedy for correcting Islamic practice and belief during his time.""

- Willis, John (2010). "Debating the Caliphate: Islam and Nation in the Work of Rashid Rida and Abul Kalam Azad". The International History Review 32 (4): 711–732. doi:10.1080/07075332.2010.534609. ISSN 0707-5332. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25762122.

- Khalaji 2009, p. 72.

- Allāh, ‘Abd (2012-02-29). "Shaykh Rashid Rida on Dar al-'Ulum Deoband" (in en). https://friendsofdeoband.wordpress.com/2012/02/29/rashid-rida-and-dar-al-ulum-deoband/.

- B. Metcalf, "Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860–1900", p. 50-60, Princeton University Press (1982).

- Rahnema 2005, p. 100.

- Rahnema 2005, p. 102.

- Rahnema 2005, pp. 104-110.

- Calvert 2010, pp. 213-217.

- Behdad 1997, pp. 40, 41.

- Behdad 1997, p. 45.

- Behdad 1997, p. 52.

- Behdad 1997, p. 46.

- Behdad 1997, p. 50.

- Behdad 1997, p. 51.

- Syed Viqar Salahuddin, Islam, peace, and conflict: based on six events in the year 1979, which were harbingers of the present day conflicts in the Muslim world, Pentagon Press (2008), p. 5

- Khalaji 2009, pp. 70-71.

- رسول جعفریان، ”جریان ها و سازمان های مذهبی سیاسی ایران“، ص٢٧١ ، ١٣٩٤ شمسی

- Khalaji 2009, p. 71.

- Bohdan 2020, p. 247.

- Behdad 1997, p. 60.

- Behdad 1997, p. 61.

- Rahnema 2005, pp. 69-70.

- Martin, Vanessa (1996). "A Comparison Between Khumainī's "Government of the Jurist" and "The Commentary on Plato's Republic" of Ibn Rushd". Journal of Islamic Studies 7 (1): 16–31. doi:10.1093/jis/7.1.16. ISSN 0955-2340. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26195475.

- Rahnema 2005, pp. 81.

- Con Coughlin (20 February 2009). Khomeini's Ghost: Iran since 1979. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-74310-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=AJ6i2-s7hoQC&q=khomeini+pepsi+roast+in+the+fires+of+hell&pg=PT107.

- Michael Axworthy. Revolutionary Iran: A History of the Islamic Republic. Oxford University Press. p. 138.

- Rahnema 2005, p. 77.

- Mashayekhi 2015, pp. 103, 107.

- Mashayekhi 2015, pp. 108-109.

- Mashayekhi 2015, p. 105.

- Mashayekhi 2015, p. 115.

- Rahnema 2005, p. 80.

- Adams, Charles J. (1983). "Maududi and the Islamic State". in Esposito, John L.. Voices of Resurgent Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503340-3. https://archive.org/details/voicesofresurgen00hcen.

- Bohdan 2020, p. 252.

- Bohdan 2020, p. 254.

- Abou el-Fadl, Khaled (2005). The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extremists. Harper. pp. 83.

- Bohdan 2020, p. 255.

- Fuchs 2021, p. 336.

- Fuchs 2021, p. 348.

- Unal, Yusuf (November 2016). "Sayyid Quṭb in Iran: Translating the Islamist Ideologue in the Islamic Republic". Journal of Islamic and Muslim Studies. Indiana University Press. 1 (2): 35–60. doi:10.2979/jims.1.2.04. JSTOR 10.2979/jims.1.2.04. S2CID 157443230 – via JSTOR.

- Bohdan 2020.

- "اخوانی گوشهنشین" (in fa). 2020-03-01. https://plus.irna.ir/news/83696140/اخوانی-گوشه-نشین.

- "President of Sadra Islamic Philosophy Research Institute". http://www.mullasadra.org/new_site/English/About%20Us/President.htm.

- Bohdan 2020, p. 249.

- Bohdan 2020, p. 250.

- Calvert 2010, pp. 165, 166.

- Keddie, Nikki R.; Matthee, Rudolph P.; Matthee, Unidel Distinguished Professor of History Rudi (2002) (in en). Iran and the Surrounding World: Interactions in Culture and Cultural Politics. University of Washington Press. pp. 281. ISBN 978-0-295-98206-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=MCXJxrOol1oC.

- Calvert 2010, p. 3.

- Rahnema 2000, pp. 274-276.

- Bohdan 2020, p. 256.

- Rahnema 2000, pp. 123-124.

- Rahnema 2000, p. 368.

- Aziz 1993, pp. 208-209.

- Aziz 1993, pp. 209-210.

- Aziz 1993, pp. 211-212.

- Aziz 1993, p. 213.

- Aziz 1993, p. 215.

- Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, 1993: p.437

- Moin, Khomeini, 1999: p.157

- Moin, Baqer (1999). Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. 158.

- "صراط النجاة - التبريزي، الميرزا جواد - کتابخانه مدرسه فقاهت" (in fa). http://shiaonlinelibrary.com/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D8%AA%D8%A8/777_%D8%B5%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B7-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%AC%D8%A7%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%B2%D8%A7-%D8%AC%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%A8%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%B2%D9%8A-%D8%AC-%D9%A1/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D9%81%D8%AD%D8%A9_9.

- Sayej 2018, p. 107.

- Ervand Abrahamian (1999). Tortured Confessions: Prisons and Public Recantations in Modern Iran. University of California Press. pp. 162–166. ISBN 978-0-520-21623-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=-QJgbEeoLfEC&pg=PA165

- Pace, Eric (1976-05-12). "A Mystery in Iran: Who Killed the Mullah?" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1976/05/12/archives/a-mystery-in-iran-who-killed-the-mullah.html.

- Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, p. 154

- Kraft, Joseph (18 December 1978). "Letter from Iran". The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1978/12/18/1978_12_18_138_TNY_CARDS_000324558?currentPage=all. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. 194–202

- Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. 194–195

- Aziz 1993, pp. 212-214.

- Rahnema 2005, pp. 89-90.

- Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. 221–222

- Ghobadzadeh, Naser; Qubādzādah, Nāṣir (1 December 2014). Religious Secularity: A Theological Challenge to the Islamic State. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199391172. https://books.google.com/books?id=b7upBAAAQBAJ.

- مطهری, مرتضی (in fa), سخنان شهید مطهری در مورد ولایت فقیه, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v3ATMTEzFuw, retrieved 2022-05-07

- Bohdan 2020, p. 257.

- 1980 April 8 – Broadcast call by Khomeini for the pious of Iraq to overthrow Saddam Hussein and his regime. Al-Dawa al-Islamiya party in Iraqi is the hoped for catalyst to start rebellion. From: Mackey, The Iranians, (1996), p.317

- Aziz 1993, p. 216.

- Aziz 1993, pp. 217-218.

- "Iraq executes coup plotters". The Salina Journal: p. 12. August 8, 1979. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/19551595/iraq_executes_coup_plotters/.

- Bay Fang. "When Saddam ruled the day." U.S. News & World Report. 11 July 2004. https://www.usnews.com/usnews/news/articles/040719/19iraq.htm

- Edward Mortimer. "The Thief of Baghdad." New York Review of Books. 27 September 1990, citing Fuad Matar. Saddam Hussein: A Biography. Highlight. 1990. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/3519

- Wright, In the Name of God (1989), p.126

- Smith, William E. (14 June 1982). "The $150 Billion Question". Time. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,950688,00.html.

- John Pike. "The Iran–Iraq War: Strategy of Stalemate". Globalsecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1985/SRE.htm.