Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aida A. Abd El-Wahed | -- | 1742 | 2022-10-19 16:59:33 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1742 | 2022-10-20 02:44:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

El-Seedi, H.R.; El-Wahed, A.A.A.; Zhao, C.; Saeed, A.; Zou, X.; Guo, Z.; Hegazi, A.G.; Shehata, A.A.; El-Seedi, H.H.R.; Algethami, A.F.; et al. Egyptian Honeybee. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/30236 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

El-Seedi HR, El-Wahed AAA, Zhao C, Saeed A, Zou X, Guo Z, et al. Egyptian Honeybee. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/30236. Accessed February 07, 2026.

El-Seedi, Hesham R., Aida A. Abd El-Wahed, Chao Zhao, Aamer Saeed, Xiaobo Zou, Zhiming Guo, Ahmed G. Hegazi, Awad A. Shehata, Haged H. R. El-Seedi, Ahmed F. Algethami, et al. "Egyptian Honeybee" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/30236 (accessed February 07, 2026).

El-Seedi, H.R., El-Wahed, A.A.A., Zhao, C., Saeed, A., Zou, X., Guo, Z., Hegazi, A.G., Shehata, A.A., El-Seedi, H.H.R., Algethami, A.F., Naggar, Y.A., Agamy, N.F., Rateb, M.E., Ramadan, M.F.A., Khalifa, S.A.M., & Wang, K. (2022, October 19). Egyptian Honeybee. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/30236

El-Seedi, Hesham R., et al. "Egyptian Honeybee." Encyclopedia. Web. 19 October, 2022.

Copy Citation

The Egyptian honeybee (Apis mellifera lamarckii) is one of the honeybee subspecies known for centuries since the ancient Egypt civilization. The subspecies of the Egyptian honeybee is distinguished by certain traits of appearance and behavior that were well-adapted to the environment and unique in a way that it is resistant to bee diseases, such as the Varroa disease. The subspecies is different than those found in Europe and is native to southern Egypt.

beekeeping

beehives

Egyptian honeybee (Apis mellifera lamarckii)

genetic analysis

1. Introduction

Beekeeping has been conducted for thousands of years; hence, the honeybee and their products have been known in ancient Egypt. Egyptians used bee products in daily life, including honey and wax, as food and in ceremonies. They also recorded their knowledge and practices on templates and tombs [1][2].

The honeybee subspecies Apis mellifera lamarckii is assumed to be the same species as the one discovered during the Pharaohs’ period [3][4]. A. m. lamarckii Cockerell, 1906 is geographically distributed in the Egyptian desert, delta region, Nile valley, and Sudan [5][6][7]. Lamarck’s honeybee was previously known as Apis fasciata Latreille and is considered an offshoot of adansonii. It resembles the lighter, yellow-banded varieties with very dark drones, and the width of the worker cells is identical to that of adansonii from center to center [7]. Lamarck’s bee is described as a good housekeeper but a poor honey producer. Thus, the Carniolan honeybee, which gained popularity because it is peaceful and easy to manage in modern Langstroth hives, thus effectively replaced the A. m. lamarckii in commercial beekeeping in Egypt.

As a result, the native honeybee population in Egypt was suppressed and predominantly centered in the Manfalut area of the Assiut governorate, which was surrounded by hybrids from Europe. A. m. lamarckii was introduced to the Dakhla oasis in 1928, and was utilized there until 1960, when the New Valley Government decided to breed less aggressive bees than A. m. lamarckii [8][9]. A large number of A. m. lamarckii colonies (about 400,000) were found in traditional mud-tube hives in the Assiut Governorate and small populations in isolated oases of Egypt [10]. The A. m. Lamarckii is noticeably smaller and has legs and wings that are shorter. Compared to the European subspecies, its colonies have fewer bees. It does not store food for the winter or form winter clusters, and it does not stop reproducing for practically the entire year. It is viewed as a representative model of the tropical African bees in general [11].

The phylogenetic analyses of A. m. lamarckii and other subspecies demonstrated a close relationship between A. m. lamarckii and A. m. syriaca (Syrian honeybee) [12]. A. m. lamarckii has various distinctive characteristics, including a higher quality of reared queens [10], A. m. lamarckii exerts high levels of defensive behavior [13]. The Egyptian honeybee exhibits a more combative defensive response when compared to European bees, and the A. m. lamarckii larva develops more quickly; hence, they tolerate Varroa destructor mites, the serious and dangerous pest to Apis mellifera species [9]. Additionally, the biochemical and molecular characterization for three subspecies of honey bee workers explained the high genetic gap of 0.25 separating the Egyptian A. m. lamarckii subspecies from the other two subspecies, A. m. ligustica (Italian), and A. m. carnica (Carniolan) [14].

2. The History of Beekeeping in Egypt and Its Current Situation

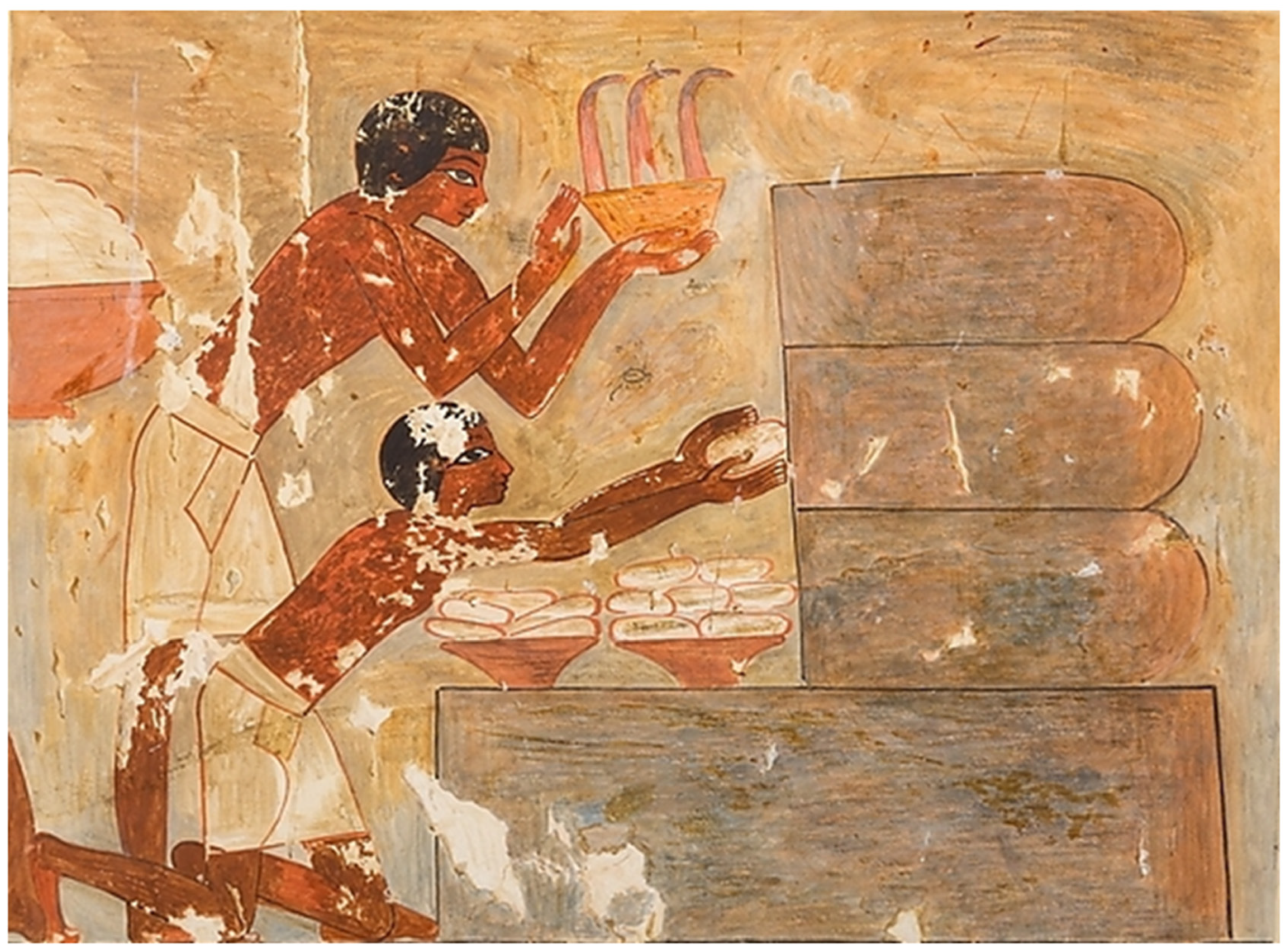

Honey is a natural product produced by bees and used in Egypt not only as a sweetener but also associated with medical practices, and was deemed a poison for ghosts, demons, evil spirits, and the dead, representing a symbol of resurrection [15]. The first crude examples of the honeybee hieroglyphs were carved by the Egyptians of the first dynasty, in approximately 3000 B.C.E [2][3][4][16]. In the Nile Valley region, the bees were used as a source of honey from the earliest years; thus, bees were highly appreciated insects by the ancient Egyptians. In the old kingdom, the earliest inscription exemplifying beekeeping came from the sun temple of pharaoh Newossere in the fifth dynasty and back to 2450 B.C.E. [17]. In the sun temple, a room adjacent to the central obelisk was discovered by Ludwig Borchardt in 1898 and called “The Chamber of the Seasons” as it contains reliefs of activities that happened at particular times of the year, and one of them was found to be the oldest evidence of beekeeping [1][17]. The bas-relief from left to right shows four scenes: (I) a beekeeper working with the beehives; (II) three men pouring honey into containers; (III) two men processing honey (this scene is mostly missing); (IV) a beekeeper sealing honey in a vessel for storage [1]. By the end of the old kingdom and during the sixth dynasty, honey production increased to the level of trading [16]. During the time of the new kingdom, there were many tombs with images illustrating the practices involved in the treatment using bees and their products [18]. In the tomb of the 18th Dynasty vizier Rekhmire, there were inscriptions demonstrating honeycombs gathering from large horizontal hives, as shown in Figure 1, pouring the honey into large vessels, the successive honey sealing in diamond-shaped containers, and comb pulverizing [1]. During the 26th dynasty, the tomb of Pabasa demonstrated one of the most famous beekeeping reliefs in Egypt, where a beekeeper is facing a group of honeybee and a series of horizontal hives with his hands held up in praise. These horizontal hives were similar to the carved hives of the old kingdom from Newossere Any’s sun temple, as shown in Figure 2. They also authenticated the continued value of the honey and the honeybee in the ancient Egyptian times and the progress of hives types throughout the time [1][19][20].

Figure 1. Honey combs gathering from large horizontal hives in Rekhmira tomb.

Figure 2. Beekeeping reliefs from the tomb of Pabasa and Karnak Temple (Photography by Aida Abd El-Wahed).

In the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.E.), the state taxed bee keeping and the bee derived products. In the Nile Valley, beekeeping processes and breeding programs were established, as honey was fundamental to the people’s food [15]. The Egyptian mud hives (traditional bee hives) were placed in piles that could reach hundreds and were combined by pouring mortar in-between [21][22]. In 1918, modern beekeeping started in Egypt using wooden Langstroth frames. In 1920, the first association of beekeepers was established to improve beekeeping process and develop its marketing. Since, then traditional beekeeping methods were used in parallel with modern ones.

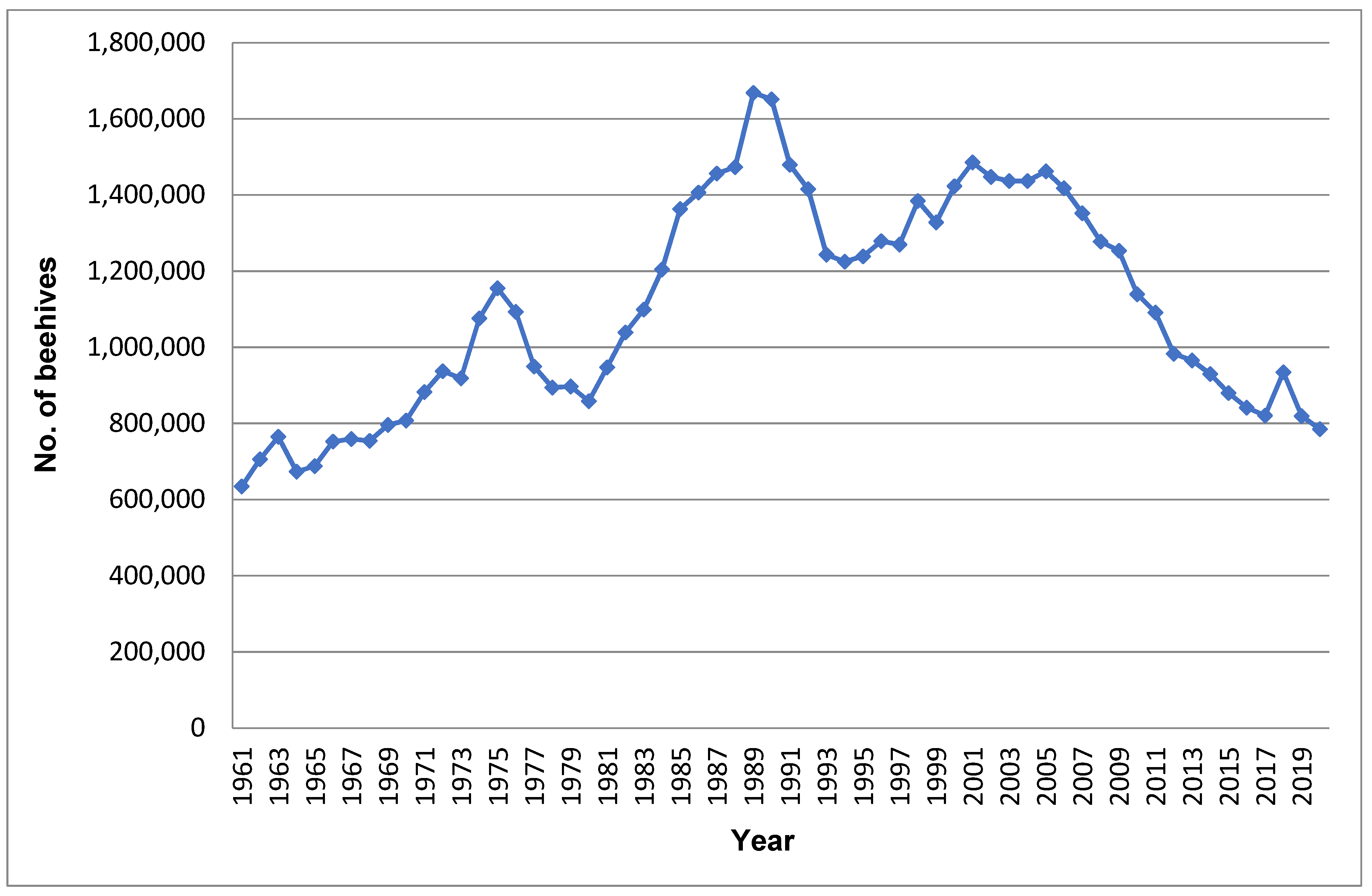

The modern beekeeping represents 99% of the used practices in Egypt [9]. Figure 3 illustrates the difference between the Egyptian mud traditional hives (A1-3) and the modern wooden ones (B). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), statistics on the number of beehives in Egypt between 1961–2020 have been fluctuating, as represented in Figure 4. The number of beehives demonstrated noticeable increases between 1964–1972, 1980–1990, and 1999–2001, reaching 937,000, 1,651,000, and 1,485,000 hives, respectively, at the end of each period. In contrast, they demonstrated noticeable decreases in 1980, 1994, and 2017, reaching 858,000, 1,225,000, and 820,516 hives, respectively [9].

Figure 3. The Egyptian mud traditional hives (A1–A3) and modern ones (B). (Photo A1–A3: Dahy M. Mostafa and used with permission).

Figure 4. Beehives stocks in Egypt within the period (1961–2020) according to FAO (Data source: www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL, accessed on 29 July 2022).

Honey bees are given special attention in Egypt because of their importance in pollination and their impact on the economy [23]. The pollination is mainly conducted using the Egyptian clover blooming during June, cotton flowering during August–September, and a minor contribution of citrus in April [21][22]. In the future, thermal stress on the Egyptian honey bee colonies will be a significant problem for beekeepers, especially during summer [24][25].

3. Apis mellifera lamarckii Morphology

The Egyptian A. m. lamarckii is considered an offshoot of adansonii. [7]. Some morphometric characteristics of Egyptian A. m. lamarckii, African Apis mellifera scutellata, and Apis mellifera jemenitica were reported where these subspecies were very close to A. m. lamarckii, as mentioned in Table 1, using different techniques such as an electron microscope [7][11][26][27][28][29][30]. Otherwise, the average length of the honeybee forewing in difference races was reported. The highest average was 10.700 mm in A. m. florea, while the lowest average was 8.275 mm in A. m. lamarckii. The average head length on different races in adult gave the highest average of 5.575 mm in A. m. lamarckii, while the lowest average was 3.750 mm in A. mellifera ligustica [29]. The mean body mass of the European (Apis mellifera Carnica) bee amounted to 120 mg, while the Egyptian bee to 78 mg. This shows that the Egyptian bee is much smaller than the European one, with only 65% of its mass. Similar results related to the thorax masses of both subspecies differ significantly (33 mg vs. 24 mg) for the European and Egyptian bee, respectively. The Egyptian bee is characterized with shorter wing size (45 mm) compared to the European bee (55 mm). The Egyptian honeybee A. m. lamarckii is significantly smaller, slimmer, and has shorter wings and legs. Moreover, the wing load was 17 and 21 Nm−2 for the Egyptian and European bee, respectively [11].

Table 1. Morphological characters of Apis mellifera lamarckii compared to African Apis mellifera scutellata and Apis mellifera jemenitica.

| Morphology Characteristics | Apis mellifera lamarckii | African Apis mellifera scutellata | Apis mellifera jemenitica | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Lighter yellow-banded varieties with very dark drones | - | - | [7] |

| Width of worker cells | 4.8 mm | - | - | [7] |

| Average head width | 4.550 mm | - | - | [28] |

| Bodyweight | 78 mg | - | 87.65 mg | [11][31] |

| Body size | 56.82 mm | 55.04 mm | 54.07 mm | [32] |

| Thorax mass | 24 mg | - | - | [11] |

| Wing load | 17 Nm−2 | - | - | [11] |

| Wing size | 45 mm2 | - | - | [11] |

| Average length of forewing | 5.575 mm | - | - | [28] |

| Forewing width | 2.78–2.96 mm | 2.71–3.03 mm | 2.44, 3.20–3.03 and 2.77–3.23 mm | [26][27][33][34][35] |

| Leg size | 7.39 mm | - | - | [27] |

| Forewing length | 8.23 and 8.74 mm | 8.48–9.01 mm | 7.94, 7.53–9.01, 7.94, and 7.55–9.39 mm | [26][27][31][33][34][35][36][37] |

| Tongue length | 5.75 mm | - | - | [26] |

| Hindwing length | 6.11 mm | 4.02–4.24 mm | 5.85 mm | [26][31][32][33][36] |

| Hindwing width | 1.76 mm | 1.52–168 mm | 1.67 mm | [26][33] |

| Femur length | 2.24 mm | 2.44–1.63 mm | 2.44, 2.39–1.63 mm | [26][33][34] |

| Tibia length | 2.82 mm | 3.05–3.23 mm | 2.55, 2.69–3.23 mm | [26][31][33][34] |

| Tibia width | - | - | 1.12 mm | [31] |

| Basitarsus length | 2.13 mm | 1.81–2.02 mm | - | [26][33] |

| Basitarsus width | 1.10 mm | 1.05–1.15 mm | - | [26][33] |

| Cubital index | 2.33 and 2.94 mm | 1.77–2.86 & 2.33 mm | 2.10–2.86 and 2.36 mm | [26][32][33][34][37] |

| Number of hooks | 20.34 | - | - | [26] |

| Lengths of the workers flagella | 2.60–2.80 mm | - | 2.29–2.80 mm | [29][34] |

| Lengths of the queens flagella | 2.60 mm | - | - | [29] |

| Lengths of the half-queen flagella | 2.48–2.60 mm | - | - | [29] |

| Length waxmirror | 1.11 mm | 1.16–1.32 mm | - | [27][33] |

| Waxmirror index | 0.55 mm | - | - | [27] |

| Hair length | 21.49 mm | 20.88 mm | 22.55 mm | [32] |

| Length of hind leg | 738.09 mm | 741.10 mm | 717.71 mm | [32][34] |

| Wing angle J16 | 98.42 | - | - | [32] |

| Proboscis length | 5.65–570 mm | - | 5.28, 5.30 and 4.84–5.74 mm | [31][34][36] |

| Metatarsus length | 1.88–1.91 mm | - | 2.03, 2.22 and 1.94–2.26 mm | [31][34][36] |

| Metatarsus width | 1.05–1.08 mm | - | 1.10, 1.01 and 0,97–1.16 mm | [31][34][36] |

| Wax mirror width | - | - | 2.00 mm | [34] |

| Total length of antenna | 3.92 mm | - | 3.64 mm | [31][36] |

(-): No reported.

The Egyptian honeybee A. m. lamarckii neither forms winter clusters nor stores food for overwintering and breed nearly throughout the year. A. m. lamarckii is forced to form winter clusters and to store food for unfavorable periods [11].

References

- Kritsky, G. The quest for the perfect hive: Ancient Mediterranean origins. In Beekeeping in the Mediterranean from Antiquity to the Resent; Agricultural Organization “Demeter” Athens: Athens, Greece, 2017; pp. 50–56.

- Kuropatnicki, A.K.; Kłósek, M.; Kucharzewski, M. Honey as medicine: Historical perspectives. J. Apic. Res. 2018, 57, 113–118.

- Sheppard, W.S.; Shoukry, A.K.S. The Nile honey bee—The bee of ancient Egypt in modern times. Am. Bee J. 2001, 14, 260–263.

- Abushady, A.Z. Races of bees. In The Hive and the Honey Bee; Dadant & Sons: Hamilton, NY, USA, 1949; pp. 11–20.

- Abdullah, I.; Gary, S.R.; Marla, S. Field trial of honey bee colonies bred for mechanisms of resistance against Varroa destructor. Apidologie 2007, 38, 67–76.

- Fasasi, K.A.; Malaka, S.L.O.; Amund, O.O. Studies on the life cycle and morphometrics of honeybees, Apis mellifera adansonii (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in a Mangrove area of Lagos, Nigeria. Ife J. Sci. 2011, 13, 103–109.

- Smith, F.G. The races of honeybees in Africa. Bee World 1961, 42, 255–260.

- Simonthomas, R.T.; Simonthomas, A.M.J. Philanthus triangulum and its recent eruption as a predator of honeybees in an Egyptian oasis. Bee World 1980, 61, 97–107.

- Al Naggar, Y.; Codling, G.; Giesy, J.P.; Safer, A. Beekeeping and the need for pollination from an agricultural perspective in Egypt. Bee World 2018, 95, 107–112.

- Masry, S.H.D.; Ebadah, I.M.A.; Abd El-Wahab, T.E. Impact of honey bee colonies of different races on rearing Apis mellifera lamarckii queen larvae. Egypt. J. plant Prot. 2013, 8, 28–35.

- Schmolz, E.; Dewitz, R.; Schricker, B.; Lamprecht, I. Energy metabolism of European (Apis mellifera Carnica) and Egyptian (A. m. lamarckii) honeybees. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2001, 65, 131–140.

- Abou-Shaara, H.F.; Eid, K.S.A.; Bayoumi, S.R. Insights into the mtDNA of the Egyptian honey bees, Apis mellifera lamarckii using different analytical tools. J. Entomol. Res. 2020, 44, 575–580.

- Kamel, S.M.; Strange, J.P.; Sheppard, W.S. A scientific note on hygienic behavior in Apis mellifera lamarckii and A. m. carnica in Egypt. Apidologie 2003, 34, 189–190.

- El-Bermawy, S.M.; Ahmed, K.S.; Al-Gohary, H.Z.; Bayomy, A.M. Biochemical and molecular characterization for three subspecies of honey bee worker, Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Egypt. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. A Entomol. 2012, 5, 103–115.

- Bunson, M. Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt; Infobase Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 1438109970.

- Kritsky, G. The Tears of Re: Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; ISBN 0199361398.

- Kritsky, G. Beekeeping from antiquity through the middle ages. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 249–264.

- Allon, N. The Tears of Re: Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt. J. Am. Orient. Soc. 2019, 139, 775–777.

- Hammad, M. Bees and beekeeping in ancient Egypt (a historical study) ancient Egyptian bee and its nature. J. Assoc. Arab Univ. Tour. Hosp. 2018, 15, 1–16.

- Leek, F.F. Some evidence of bees and honey in ancient Egypt. Bee World 1975, 56, 141–163.

- Gupta, R.K.; Khan, M.S.; Srivastava, R.M.; Goswami, V. History of beekeeping in developing world. In Beekeeping for Poverty Alleviation and Livelihood Security; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3–62.

- Hussein, M.H. A review of beekeeping in Arab countries. Bee World 2000, 81, 56–71.

- Amro, A.M. Pollinators and pollination effects on three canola (Brassica napus L.) cultivars: A case study in Upper Egypt. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101240.

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Elshafiey, E.H.; Shetaia, A.A.; El-Wahed, A.A.A.; Algethami, A.F.; Musharraf, S.G.; Alajmi, M.F.; Zhao, C.; Masry, S.H.D.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; et al. Overview of bee pollination and its economic value for crop production. Insects 2021, 12, 688.

- Abou-Shaara, H.F. Expectations about the potential impacts of climate change on honey bee colonies in Egypt. J. Apic. 2016, 31, 157–164.

- Abou-Shaara, H.F.I. Morphometrical, Biological and Behavioral Studies on Some Honey Bee Races at El-Beheira Governorate. Doctoral Dissertation, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt, 2009.

- Shaibi, T.; Fuchs, S.; Moritz, R.F.A. Morphological study of honeybees (Apis mellifera) from Libya. Apidologie 2009, 40, 97–105.

- Rukhosh, J.R. The morphometrical study of some honeybee (Apis mellifera L.)(Hymenoptera: Apidae) races in Sulaimani-Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Euphrates J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 13, 23–41.

- Zeid, A.S.A.; Schricker, B. Antennal sensilla of the queen, half-queen and worker of the Egyptian honey bee, Apis mellifera lamarckii. J. Apic. Res. 2001, 40, 53–58.

- Ahmed, K.-A.; El-Bermawy, S.; El-Gohary, H.; Bayomy, A. Electron microscope study on workers antennae and sting lancets of three subspecies of honey bee Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and its bearing on their phylogeny. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. A Entomol. 2015, 8, 105–124.

- Al-Kahtani, S.N.; Taha, E.K.A. Morphometric study of Yemeni (Apis mellifera jemenitica) and Carniolan (A. m. carnica) honeybee workers in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247262.

- Meixner, M.D.; Leta, M.A.; Koeniger, N.; Fuchs, S. The honey bees of Ethiopia represent a new subspecies of Apis mellifera—Apis mellifera simensis n. ssp. Apidologie 2011, 42, 425–437.

- Buco, S.M.; Collins, A.M.; Rinderer, T.E.; Lancaster, V.A.; Sylvester, H.A.; Crewe, R.M.; Davis, G.L. Morphometric differences between south American Africanized and South African Scutellata ) honey bees. Apidologie 1987, 18, 217–222.

- Alabdali, E.A.; Ghramh, H.A.; Ibrahim, E.H.; Ahmad, Z.; Asiri, A.N. Characterization of the native honey bee (Apis mellifera jemenitica) in the south western region of Saudi Arabia using morphometric and genetic (mtDNA COI) characteristics. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2278–2284.

- Alqarni, A.S.; Hannan, M.A.; Owayss, A.A.; Engel, M.S. The indigenous honey bees of Saudi Arabia (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Apis mellifera jemenitica Ruttner): Their natural history and role in beekeeping. Zookeys 2011, 134, 83–98.

- Elfeel, M.A.M. Studies on the Egyptian Honeybee Race Apis mellifera lamarckii Cockerel in Siwa Oasis as a New Isolated Region; Cairo University: Cairo, Egypt, 2008.

- Alburaki, A. Morphometrical study on Syrian honeybee (Apis mellifera syriaca) introduction important social insects known in the honeybee evolutionary lineages (Ruttner, 1978). Biometrical studies were also done on other honeybee species Abd. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2008, 20, 89–93.

More

Information

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Oct 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No