| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Molika Sinha | -- | 1566 | 2022-10-19 00:01:09 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | -3 word(s) | 1563 | 2022-10-19 04:30:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

It is well-established that cancer and normal cells can be differentiated based on the altered sequence and expression of specific proteins. There are only a few examples, showing that cancer and normal cells can be differentiated based on the altered distribution of proteins within intracellular compartments. there are available data on shifts in the intracellular distribution of two proteins, the membrane associated beta-catenin and the actin-binding protein CapG. Both proteins show altered distributions in cancer cells compared to normal cells. These changes are noted (i) in steady state and thus can be visualized by immunohistochemistry—beta-catenin shifts from the plasma membrane to the cell nucleus in cancer cells; and (ii) in the dynamic distribution that can only be revealed using the tools of quantitative live cell microscopy—CapG shuttles faster into the cell nucleus of cancer cells. Both proteins may play a role as prognosticators in gynecologic malignancies: beta-catenin in endometrial cancer and CapG in breast and ovarian cancer. Thus, both proteins may serve as examples of altered intracellular protein distribution in cancer and normal cells.

1. Introduction

2. Beta-Catenin

2.1. Beta-Catenin and Cancer

2.2. Change of the Steady-State Distribution of Beta-Catenin in Endometrial Cancer

3. CapG

3.1. CapG and Cancer

3.2. Change in the Dynamic Distribution of CapG in Breast Cancer

References

- Albuquerque, C.; Breukel, C.; van der Luijt, R.; Fidalgo, P.; Lage, P.; Slors, F.J.; Leitao, C.N.; Fodde, R.; Smits, R. The ‘just-right’ signaling model: APC somatic mutations are selected based on a specific level of activation of the beta-catenin signaling cascade. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 1549–1560.

- Segditsas, S.; Rowan, A.J.; Howarth, K.; Jones, A.; Leedham, S.; Wright, N.A.; Gorman, P.; Chambers, W.; Domingo, E.; Roylance, R.R.; et al. APC and the three-hit hypothesis. Oncogene 2009, 28, 146–155.

- Nusse, R.; Varmus, H.E. Many tumors induced by the mouse mammary tumor virus contain a provirus integrated in the same region of the host genome. Cell 1982, 31, 99–109.

- Wellenstein, M.D.; Coffelt, S.B.; Duits, D.E.M.; van Miltenburg, M.H.; Slagter, M.; de Rink, I.; Henneman, L.; Kas, S.M.; Prekovic, S.; Hau, C.S.; et al. Loss of p53 triggers WNT-dependent systemic inflammation to drive breast cancer metastasis. Nature 2019, 572, 538–542.

- Luga, V.; Zhang, L.; Viloria-Petit, A.M.; Ogunjimi, A.A.; Inanlou, M.R.; Chiu, E.; Buchanan, M.; Hosein, A.N.; Basik, M.; Wrana, J.L. Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell 2012, 151, 1542–1556.

- Harper, K.L.; Sosa, M.S.; Entenberg, D.; Hosseini, H.; Cheung, J.F.; Nobre, R.; Avivar-Valderas, A.; Nagi, C.; Girnius, N.; Davis, R.J.; et al. Mechanism of early dissemination and metastasis in Her2(+) mammary cancer. Nature 2016, 540, 588–592.

- Xu, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Evert, M.; Calvisi, D.F.; Chen, X. Beta-Catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e154515.

- Aguilera, K.Y.; Dawson, D.W. WNT Ligand Dependencies in Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 671022.

- Kandoth, C.; Schultz, N.; Cherniack, A.D.; Akbani, R.; Liu, Y.; Shen, H.; Robertson, A.G.; Pashtan, I.; Shen, R. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013, 497, 67–73.

- Wright, K.; Wilson, P.; Morland, S.; Campbell, I.; Walsh, M.; Hurst, T.; Ward, B.; Cummings, M.; Chenevix-Trench, G. beta-catenin mutation and expression analysis in ovarian cancer: Exon 3 mutations and nuclear translocation in 16% of endometrioid tumours. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 82, 625–629.

- Costigan, D.C.; Dong, F.; Nucci, M.R.; Howitt, B.E. Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Correlates of CTNNB1 Mutated Endometrial Endometrioid Carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2020, 39, 119–127.

- Kurnit, K.C.; Kim, G.N.; Fellman, B.M.; Urbauer, D.L.; Mills, G.B.; Zhang, W.; Broaddus, R.R. CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) mutation identifies low grade, early stage endometrial cancer patients at increased risk of recurrence. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 1032–1041.

- Southwick, F.S.; DiNubile, M.J. Rabbit alveolar macrophages contain a Ca2+-sensitive, 41,000-dalton protein which reversibly blocks the “barbed” ends of actin filaments but does not sever them. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 14191–14195.

- Yu, F.X.; Johnston, P.A.; Sudhof, T.C.; Yin, H.L. gCap39, a calcium ion- and polyphosphoinositide-regulated actin capping protein. Science 1990, 250, 1413–1415.

- Akin, O.; Mullins, R.D. Capping protein increases the rate of actin-based motility by promoting filament nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Cell 2008, 133, 841–851.

- Silacci, P.; Mazzolai, L.; Gauci, C.; Stergiopulos, N.; Yin, H.L.; Hayoz, D. Gelsolin superfamily proteins: Key regulators of cellular functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 2614–2623.

- Sun, H.Q.; Kwiatkowska, K.; Wooten, D.C.; Yin, H.L. Effects of CapG overexpression on agonist-induced motility and second messenger generation. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 129, 147–156.

- Van Impe, K.; De Corte, V.; Eichinger, L.; Bruyneel, E.; Mareel, M.; Vandekerckhove, J.; Gettemans, J. The Nucleo-cytoplasmic actin-binding protein CapG lacks a nuclear export sequence present in structurally related proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 17945–17952.

- Pellieux, C.; Desgeorges, A.; Pigeon, C.H.; Chambaz, C.; Yin, H.; Hayoz, D.; Silacci, P. Cap G, a gelsolin family protein modulating protective effects of unidirectional shear stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 29136–29144.

- Dahl, E.; Sadr-Nabavi, A.; Klopocki, E.; Betz, B.; Grube, S.; Kreutzfeld, R.; Himmelfarb, M.; An, H.X.; Gelling, S.; Klaman, I.; et al. Systematic identification and molecular characterization of genes differentially expressed in breast and ovarian cancer. J. Pathol. 2005, 205, 21–28.

- Glaser, J.; Neumann, M.H.; Mei, Q.; Betz, B.; Seier, N.; Beyer, I.; Fehm, T.; Neubauer, H.; Niederacher, D.; Fleisch, M.C. Macrophage capping protein CapG is a putative oncogene involved in migration and invasiveness in ovarian carcinoma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 379847.

- Lovero, D.; D’Oronzo, S.; Palmirotta, R.; Cafforio, P.; Brown, J.; Wood, S.; Porta, C.; Lauricella, E.; Coleman, R.; Silvestris, F. Correlation between targeted RNAseq signature of breast cancer CTCs and onset of bone-only metastases. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126, 419–429.

- Westbrook, J.A.; Cairns, D.A.; Peng, J.; Speirs, V.; Hanby, A.M.; Holen, I.; Wood, S.L.; Ottewell, P.D.; Marshall, H.; Banks, R.E.; et al. CAPG and GIPC1: Breast Cancer Biomarkers for Bone Metastasis Development and Treatment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djv360.

- Da Costa, G.G.; Gomig, T.H.; Kaviski, R.; Santos Sousa, K.; Kukolj, C.; De Lima, R.S.; De Andrade Urban, C.; Cavalli, I.J.; Ribeiro, E.M. Comparative Proteomics of Tumor and Paired Normal Breast Tissue Highlights Potential Biomarkers in Breast Cancer. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2015, 12, 251–261.

- Thompson, C.C.; Ashcroft, F.J.; Patel, S.; Saraga, G.; Vimalachandran, D.; Prime, W.; Campbell, F.; Dodson, A.; Jenkins, R.E.; Lemoine, N.R.; et al. Pancreatic cancer cells overexpress gelsolin family-capping proteins, which contribute to their cell motility. Gut 2007, 56, 95–106.

- Bahrami, S.; Gheysarzadeh, A.; Sotoudeh, M.; Bandehpour, M.; Khabazian, R.; Zali, H.; Hedayati, M.; Basiri, A.; Kazemi, B. The Association Between Gelsolin-like Actin-capping Protein (CapG) Overexpression and Bladder Cancer Prognosis. Urol. J. 2020, 18, 186–193.

- Van Ginkel, P.R.; Gee, R.L.; Walker, T.M.; Hu, D.N.; Heizmann, C.W.; Polans, A.S. The identification and differential expression of calcium-binding proteins associated with ocular melanoma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1448, 290–297.

- Chen, Z.F.; Huang, Z.H.; Chen, S.J.; Jiang, Y.D.; Qin, Z.K.; Zheng, S.B.; Chen, T. Oncogenic potential of macrophagecapping protein in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 1.

- Nader, J.S.; Boissard, A.; Henry, C.; Valo, I.; Verriele, V.; Gregoire, M.; Coqueret, O.; Guette, C.; Pouliquen, D.L. Cross-Species Proteomics Identifies CAPG and SBP1 as Crucial Invasiveness Biomarkers in Rat and Human Malignant Mesothelioma. Cancers 2020, 12, 2430.

- Lal, A.; Lash, A.E.; Altschul, S.F.; Velculescu, V.; Zhang, L.; McLendon, R.E.; Marra, M.A.; Prange, C.; Morin, P.J.; Polyak, K.; et al. A public database for gene expression in human cancers. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 5403–5407.

- Fu, Q.; Shaya, M.; Li, S.; Kugeluke, Y.; Dilimulati, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Q. Analysis of clinical characteristics of macrophage capping protein (CAPG) gene expressed in glioma based on TCGA data and clinical experiments. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 1344–1350.

- Yun, D.P.; Wang, Y.Q.; Meng, D.L.; Ji, Y.Y.; Chen, J.X.; Chen, H.Y.; Lu, D.R. Actin-capping protein CapG is associated with prognosis, proliferation and metastasis in human glioma. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 1011–1022.

- Xing, W.; Zeng, C. An integrated transcriptomic and computational analysis for biomarker identification in human glioma. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 7185–7192.

- Kimura, K.; Ojima, H.; Kubota, D.; Sakumoto, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Tomonaga, T.; Kosuge, T.; Kondo, T. Proteomic identification of the macrophage-capping protein as a protein contributing to the malignant features of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Proteom. 2013, 78, 362–373.

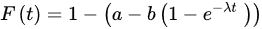

- Renz, M.; Betz, B.; Niederacher, D.; Bender, H.G.; Langowski, J. Invasive breast cancer cells exhibit increased mobility of the actin-binding protein CapG. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 1476–1482.

- Axelrod, D.; Koppel, D.E.; Schlessinger, J.; Elson, E.; Webb, W.W. Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 1976, 16, 1055–1069.

- Edidin, M.; Zagyansky, Y.; Lardner, T.J. Measurement of membrane protein lateral diffusion in single cells. Science 1976, 191, 466–468.

- Ellenberg, J.; Siggia, E.D.; Moreira, J.E.; Smith, C.L.; Presley, J.F.; Worman, H.J.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Nuclear membrane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: Targeting of an inner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 138, 1193–1206.

- Soumpasis, D.M. Theoretical analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery experiments. Biophys. J. 1983, 41, 95–97.