| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antonios Koutras | -- | 2279 | 2022-10-18 11:02:00 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | + 2 word(s) | 2281 | 2022-10-18 11:09:41 | | | | |

| 3 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 2281 | 2022-10-21 08:00:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

According to McCormik and Peterson (2018), the most common cancers of reproductive age in women are melanoma, breast cancer (the most common gestational cancer and reaches 20% of cases), thyroid cancer, cervical cancer, and lymphomas (most commonly Hodgkin’s lymphoma). A pregnancy that coexists with cancer is not an ordinary pregnancy and consists of a complex medical condition. In the majority of these cases, various therapeutic and ethical dilemmas arise.

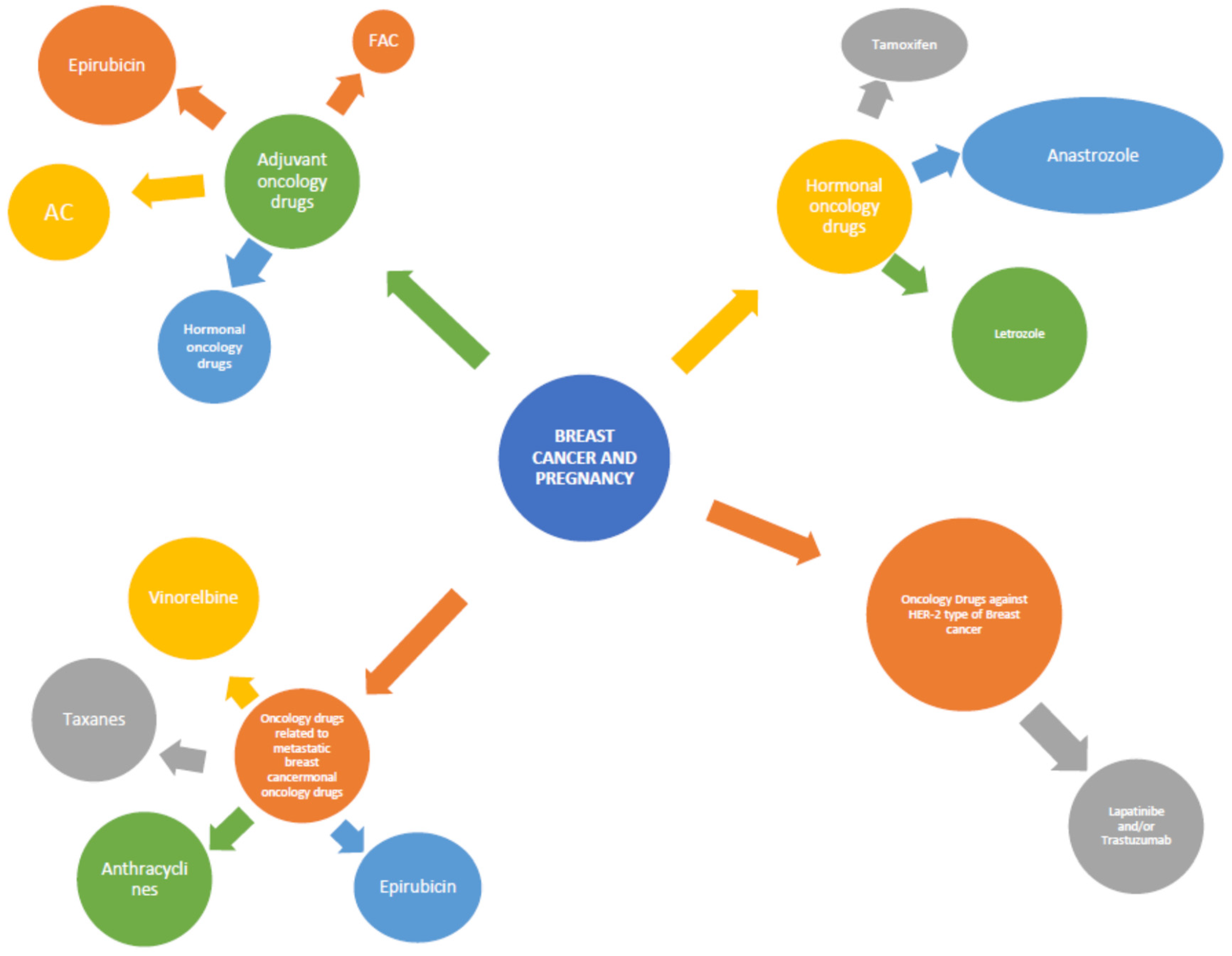

1. Pregnancy and Anticancer Drug Treatment for the Breast Cancer

1.1. The Adjuvant Oncology Drugs

1.2. Hormonal Oncology Drugs

1.3. Oncology Drugs against HER-2 Type Breast Cancer

1.4. Oncology Drugs Related to Metastatic Breast Cancer

2. Pregnancy and Anti-Cancer Drug Treatment for Melanoma

Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer and constitutes one of the most common cancers in pregnant women. Treating melanoma includes surgery and is followed by drug treatment in uncontrolled cases, especially in cases of metastases [15]. The oncology drugs used to treat melanoma are (1) dabrafenib, which is strictly contraindicated during pregnancy, as it has been shown to be teratogenic [15][16] and (2) ipilimumab, which should be administered in accordance with strict protocols, as it is responsible for fetal death and premature birth [15]; (3) imatinib is responsible for a large proportion of congenital malformations [17][18]. (4) Cisplatin has been shown to be responsible for miscarriages and teratogenesis [19]. Finally, (5) dacarbazine, which is considered to be the most effective approach in the treatment of metastatic melanoma and did not appear to be responsible for fetal deaths or fetal malformations. It is usually combined with other chemotherapeutic agents, such as bleomycin, vincristine, and lomustine [20][21][22] (Figure 2).

.

3. Pregnancy and Anti-Cancer Drug Treatment for the Cervix

4. Pregnancy and Anti-Cancer Drug Treatment for Ovarian Cancer

5. Pregnancy and Anti-Cancer Drug Treatment for Thyroid Cancer

6. Pregnancy and Anti-Cancer Drug Treatment of Lymphomas

-

Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP): This therapeutic option does not appear to present significant defects in fetuses if administered after the first three months of gestation [41]. However, it is reported that it can adversely affect the fertility of people of a reproductive age. At the same time, the pregnant woman receiving treatment may experience the following: neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, alopecia, insomnia, fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, etc. Therefore, the treating physician should be suspicious and closely monitor the progress of the patient [42];

-

Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and adriamycin (CHOP): This scheme has proven to be safe if administered after the first trimester but not earlier [41];

7. Pregnancy and Other Cancers

8. Pregnancy and Lung Cancer

9. Pregnancy and Brain Tumors

10. Pregnancy and Leukemia

11. Pregnancy and Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia

References

- Peccatori, F.A.; Azim, H.A.; Orecchia, R.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Pavlidis, N.; Kesic, V.; Pentheroudakis, G. Cancer, Pregnancy and Fertility: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, vi160–vi170.

- Azim, H.A.; Peccatori, F.A.; Pavlidis, N. Treatment of The Pregnant Mother with Cancer: A Systematic Review on The Use of Cytotoxic, Endocrine, Targeted Agents and Immunotherapy during Pregnancy. Part I: Solid Tumors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2010, 36, 101–109.

- Peccatori, F.A.; Azim, H.A.; Scarfone, G.; Gadducci, A.; Bonazzi, C.; Gentilini, O.; Galimberti, V.; Intra, M.; Locatelli, M.; Acaia, B.; et al. Weekly Epirubicin in The Treatment of Gestational Breast Cancer (GBC). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008, 115, 591–594.

- Hahn, K.M.E.; Johnson, P.H.; Gordon, N.; Kuerer, H.; Middleton, L.; Ramirez, M.; Yang, W.; Perkins, G.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Theriault, R.L. Treatment of Pregnant Breast Cancer Patients and Outcomes of Children Exposed to Chemotherapy in Utero. Cancer 2006, 107, 1219–1226.

- Pereg, D.; Lishner, M. Maternal and Fetal Effects of Systemic Therapy in The Pregnant Woman with Cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2008, 178, 21–38.

- Sharma, G.N.; Dave, R.; Sanadya, J.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, K.K. Various types and management of breast cancer: An overview. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2010, 1, 109–126.

- Braems, G.; Denys, H.; De Wever, O.; Cocquyt, V.; Van den Broecke, R. Use of Tamoxifen Before and during Pregnancy. Oncologist 2011, 16, 1547–1551.

- Drugs.com, 2020. Retrieved 2021. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/anastrozole.html (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Gill, S.K.; Moretti, M.; Koren, G. Is the use of letrozole to induce ovulation teratogenic? Can. Fam. Physician. 2008, 54, 353–354.

- Beltrame, D.; di Salle, E.; Giavini, E.; Gunnarsson, K.; Brughera, M. Reproductive Toxicity of Exemestane, An Antitumoral Aromatase Inactivator, in Rats and Rabbits. Reprod. Toxicol. 2001, 15, 195–213, Erratum in Reprod. Toxicol. 2001, 15, 601–602.

- Kharb, R.; Haider, K.; Neha, K.; Yar, M.S. Aromatase Inhibitors: Role in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. Arch. Pharm. 2020, 353, 2000081.

- Lambertini, M.; Viglietti, G. Pregnancies in Young Women with Diagnosis and Treatment of HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 803–804.

- Goodyer, M.J.; Ismail, J.R.; O’Reilly, S.P.; Moylan, E.J.; Ryan, C.A.M.; Hughes, P.A.; O’Connor, A. Safety of Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) during Pregnancy: Two Case Reports. Cases J. 2009, 2, 9329.

- Azim, H.A.; Peccatori, F.A. Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancer during Pregnancy: We Need to Talk! Breast 2008, 17, 426–428.

- Still, R.; Brennecke, S. Melanoma in Pregnancy. Obstet. Med. 2017, 10, 107–112.

- Grunewald, S.; Jank, A. New systemic agents in dermatology with respect to fertility, pregnancy, and lactation. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2015, 13, 277–290.

- Pye, S.M.; Cortes, J.; Ault, P.; Hatfield, A.; Kantarjian, H.; Pilot, R.; Rosti, G.; Apperley, J.F. The Effects of Imatinib on Pregnancy Outcome. Blood 2008, 111, 5505–5508.

- Ali, R.; Ozkalemkas, F.; Ozcelik, T.; Ozkocaman, V.; Ozkan, A. Imatinib and Pregnancy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 3812–3813.

- Dipaola, R.S.; Goodin, S.; Ratzell, M.; Florczyk, M.; Karp, G.; Ravikumar, T. Chemotherapy for Metastatic Melanoma during Pregnancy. Gynecol. Oncol. 1997, 66, 526–530.

- Pagès, C.; Robert, C.; Thomas, L.; Maubec, E.; Sassolas, B.; Granel-Brocard, F.; Chevreau, C.; De Raucourt, S.; Leccia, M.; Fichet, D.; et al. Management and Outcome of Metastatic Melanoma during Pregnancy. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009, 162, 274–281.

- Vuoristo, M.-S.; Hahka-Kemppinen, M.; Parvinen, L.-M.; Pyrhönen, S.; Seppä, H.; Korpela, M.; Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P. Randomized Trial of Dacarbazine Versus Bleomycin, Vincristine, Lomustine and Dacarbazine (BOLD) Chemotherapy Combined with Natural Or Recombinant Interferon-α in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2005, 15, 291–296.

- Jhaveri, M.B.; Driscoll, M.S.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Melanoma in Pregnancy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 54, 537–545.

- Beharee, N.; Shi, Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Cervical Cancer in Pregnant Women. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 5425–5430.

- Amant, F.; Van Calsteren, K.; Halaska, M.J.; Beijnen, J.; Lagae, L.; Hanssens, M.; Heyns, L.; Lannoo, L.; Ottevanger, N.P.; Vanden Bogaert, W.; et al. Gynecologic Cancers in Pregnancy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2009, 19, S1–S12.

- Fruscio, R.; de Haan, J.; Van Calsteren, K.; Verheecke, M.; Mhallem, M.; Amant, F. Ovarian Cancer in Pregnancy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 41, 108–117.

- Pujade-Lauraine, E. New Treatments in Ovarian Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, viii57–viii60.

- Méndez, L.E.; Mueller, A.; Salom, E.; González-Quintero, V.H. Paclitaxel and Carboplatin Chemotherapy Administered during Pregnancy for Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 102, 1200–1202.

- Mir, O.; Berveiller, P.; Ropert, S.; Goffinet, F.; Goldwasser, F. Use of Platinum Derivatives during Pregnancy. Cancer 2008, 113, 3069–3074.

- Serkies, K.; Węgrzynowicz, E.; Jassem, J. Paclitaxel and Cisplatin Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer during Pregnancy: Case Report and Review of The Literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 283, 97–100.

- Ghaemmaghami, F.; Abbasi, F.; Abadi, A.G.N. A Favorable Maternal and Neonatal Outcome Following Chemotherapy with Etoposide, Bleomycin, and Cisplatin for Management of Grade 3 Immature Teratoma of The Ovary. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 20, 257–259.

- Sema, Y.; Aysun, F.; Abdullah, Y.; Ethem, U. The Follow-Up of Thyroid Disease in 188 Pregnant Women According to The Guidelines of ATA (American Thyroid Association) 2017. Reprod. Med. Int. 2020, 3.

- Khaled, H.; Al Lahloubi, N.; Rashad, N. A Review on Thyroid Cancer during Pregnancy: Multitasking Is Required. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 565–570.

- Filetti, S.; Durante, C.; Hartl, D.; Leboulleux, S.; Locati, L.; Newbold, K.; Papotti, M.; Berruti, A. Thyroid Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1856–1883.

- Østensen, M.; Khamashta, M.; Lockshin, M.; Parke, A.; Brucato, A.; Carp, H.; Doria, A.; Rai, R.; Meroni, P.L.; Cetin, I.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs and reproduction. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 2006, 8, 209.

- Imran, S.A.; Rajaraman, M. Management of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer in Pregnancy. J. Thyroid. Res. 2011, 2011, 549609.

- Pereg, D.; Koren, G.; Lishner, M. The Treatment of Hodgkin’s and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Pregnancy. Haematologica 2007, 92, 1230–1237.

- Bachanova, V.; Connors, J.M. Hodgkin Lymphoma in Pregnancy. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2013, 8, 211–217.

- Wolters, V.; Heimovaara, J.; Maggen, C.; Cardonick, E.; Boere, I.; Lenaerts, L.; Amant, F. Management of pregnancy in women with cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 314–322.

- Cotteret, C.; Pham, Y.-V.; Marcais, A.; Driessen, M.; Cisternino, S.; Schlatter, J. Maternal ABVD Chemotherapy for Hodgkin Lymphoma in a Dichorionic Diamniotic Pregnancy: A Case Report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 231.

- Avilés, A.; Neri, N. Hematological Malignancies and Pregnancy: A Final Report of 84 Children Who Received Chemotherapy in Utero. Clin. Lymphoma 2001, 2, 173–177.

- Moshe, Y.; Bentur, O.S.; Lishner, M.; Avivi, I. The Management of Hodgkin Lymphomas in Pregnancies. Eur. J. Haematol. 2017, 99, 385–391.

- Marcus, R.; Imrie, K.; Belch, A.; Cunningham, D.; Flores, E.; Catalano, J.; Solal-Celigny, P.; Offner, F.; Walewski, J.; Raposo, J.; et al. CVP Chemotherapy Plus Rituximab Compared with CVP As First-Line Treatment for Advanced Follicular Lymphoma. Blood 2005, 105, 1417–1423.

- Dawson, A.L.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; Reefhuis, J.; Arena, J.F.; the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Maternal Exposure to Methotrexate and Birth Defects: A Population-Based Study. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2014, 164, 2212–2216.

- Mantilla-Rivas, E.; Brennan, A.; Goldrich, A.; Bryant, J.R.; Oh, A.K.; Rogers, G.F. Extremity Findings of Methotrexate Embryopathy. Hand 2019, 15, NP14–NP21.

- Yates, R.; Zhang, J. Lung Cancer in Pregnancy: An Unusual Case of Complete Response to Chemotherapy. Cureus 2015, 7, e440.

- Mitrou, S.; Petrakis, D.; Fotopoulos, G.; Zarkavelis, G.; Pavlidis, N. Lung Cancer during Pregnancy: A Narrative Review. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 571–574.

- Van Calsteren, K.; Heyns, L.; De Smet, F.; Van Eycken, L.; Gziri, M.M.; Van Gemert, W.; Halaska, M.; Vergote, I.; Ottevanger, N.; Amant, F. Cancer during Pregnancy: An Analysis of 215 Patients Emphasizing The Obstetrical and The Neonatal Outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 683–689.

- Blumenthal, D.T.; Parreño, M.G.H.; Batten, J.; Chamberlain, M.C. Management of Malignant Gliomas during Pregnancy. Cancer 2008, 113, 3349–3354.

- Nolan, S.; Czuzoj-Shulman, N.; Abenhaim, H.A. Pregnancy Outcomes among Leukemia Survivors: A Population-Based Study on 14.5 Million Births. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2019, 34, 2283–2289.

- Webb, M.J.; Jafta, D. Imatinib Use in Pregnancy. Turk. J. Haematol. 2012, 29, 405–408.

- Abruzzese, E.; Trawinska, M.M.; De Fabritiis, P.; Perrotti, A.P. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and pregnancy. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 6, e2014028.

- Fracchiolla, N.S.; Sciumè, M.; Dambrosi, F.; Guidotti, F.; Ossola, M.W.; Chidini, G.; Gianelli, U.; Merlo, D.; Cortelezzi, A. Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Pregnancy: Clinical Experience from a Single Center and a Review of The Literature. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 442.

- Santolaria, A.; Perales, A.; Montesinos, P.; Sanz, M.A. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of The Literature. Cancers 2020, 12, 968.

- Verma, V.; Giri, S.; Manandhar, S.; Pathak, R.; Bhatt, V. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia during Pregnancy: A Systematic Analysis of Outcome. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 57, 616–622.

- Hoffman, M.A.; Wiernik, P.H.; Kleiner, G.J. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia and Pregnancy. a Case Report. Cancer 1995, 76, 2237–2241.

- Sham, R.L. All-Trans Retinoic Acid-Induced Labor in a Pregnant Patient with Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 1996, 53, 145.