| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camila Xu | -- | 2588 | 2022-10-17 01:30:32 |

Video Upload Options

The 1860 Oxford evolution debate took place at the Oxford University Museum in Oxford, England , on 30 June 1860, seven months after the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Several prominent British scientists and philosophers participated, including Thomas Henry Huxley, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, Benjamin Brodie, Joseph Dalton Hooker and Robert FitzRoy. The debate is best remembered today for a heated exchange in which Wilberforce supposedly asked Huxley whether it was through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed his descent from a monkey. Huxley is said to have replied that he would not be ashamed to have a monkey for his ancestor, but he would be ashamed to be connected with a man who used his great gifts to obscure the truth. One eyewitness suggests that Wilberforce's question to Huxley may have been "whether, in the vast shaky state of the law of development, as laid down by Darwin, any one can be so enamoured of this so-called law, or hypothesis, as to go into jubilation for his great great grandfather having been an ape or a gorilla?", whereas another suggests he may have said that "it was of little consequence to himself whether or not his grandfather might be called a monkey or not." The encounter is often known as the Huxley–Wilberforce debate or the Wilberforce–Huxley debate, although this description is somewhat misleading. Rather than being a formal debate between the two, it was actually an animated discussion that occurred after the presentation of a paper by John William Draper of New York University, on the intellectual development of Europe with relation to Darwin's theory (one of a number of scientific papers presented during the week as part of the British Association's annual meeting). Although Huxley and Wilberforce were not the only participants in the discussion, they were reported to be the two dominant parties. No verbatim account of the debate exists, and there is considerable uncertainty regarding what Huxley and Wilberforce actually said.

1. Background

The idea of transmutation of species was very controversial in the first half of the nineteenth century, seen as contrary to religious orthodoxy and a threat to the social order, but welcomed by Radicals seeking to widen democracy and overturn the aristocratic hierarchy. The scientific community was also wary, lacking a mechanistic theory. The anonymous publication of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in 1844 brought a storm of controversy, but attracted a wide readership and became a bestseller. At the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting at Oxford in May 1847, the Bishop of Oxford Samuel Wilberforce used his Sunday sermon at St. Mary's Church on "the wrong way of doing science" to deliver a stinging attack obviously aimed at its author, Robert Chambers, in a church "crowded to suffocation" with geologists, astronomers and zoologists. The scientific establishment also remained skeptical, but the book had converted a vast popular audience.[1]

Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published on 24 November 1859 to wide debate and controversy. The influential biologist Richard Owen wrote negative anonymous review of the book in the Edinburgh Review,[2] and also coached Wilberforce, who wrote an anonymous 17,000-word review in the Quarterly Review.[3]

Thomas Huxley, who was one of the small group with whom Darwin had shared his theory before publication, emerged as the main champion of evolution. He wrote a favourable review of the Origin in The Times in December 1859,[4] along with several other articles and a lecture at the Royal Institution in February 1860.[5]

The reaction of many orthodox churchmen was hostile, but their attention was diverted in February 1860 by a much greater furor over the publication of Essays and Reviews by seven liberal theologians. Amongst them, the Reverend Baden Powell had already praised evolutionary ideas, and in his essay he commended "Mr. Darwin's masterly volume" for substantiating "the grand principle of the self-evolving powers of nature".[1]

The controversy was at the centre of attention when the British Association for the Advancement of Science (often referred to then simply as "the BA") convened their annual meeting at the new Oxford University Museum of Natural History in June 1860. On Thursday 28 June, Charles Daubeny read a paper "On the final causes of the sexuality in plants, with particular reference to Mr. Darwin's work ..."[6] Owen and Huxley were both in attendance, and a debate erupted over Darwin's theory.[6] Owen spoke of facts which would enable the public to "come to some conclusions ... of the truth of Mr. Darwin's theory", and repeated an anatomical argument which he had first presented in 1857, that "the brain of the gorilla was more different from that of man than from that of the lowest primate particularly because only man had a posterior lobe, a posterior horn, and a hippocampus minor." Huxley was convinced this was incorrect, and had researched its errors. For the first time he spoke publicly on this point, and "denied altogether that the difference between the brain of the gorilla and man was so great" in a "direct and unqualified contradiction" of Owen, citing previous studies as well as promising to provide detailed support for his position.[7]

Wilberforce agreed to address the meeting on Saturday morning, and there was expectation that he would repeat his success at scourging evolutionary ideas as at the 1847 meeting. Huxley was initially reluctant to engage Wilberforce in a public debate about evolution, but, in a chance encounter, Robert Chambers persuaded him not to desert the cause.[6][8] The Reverend Baden Powell would have been on the platform, but he had died of a heart attack on 11 June.[1]

2. Debate

Word spread that Bishop Wilberforce, known as "Soapy Sam" (from a comment by Benjamin Disraeli that the Bishop's manner was "unctuous, oleaginous, saponaceous"), would speak against Darwin's theory at the meeting on Saturday 30 June 1860. Wilberforce was one of the greatest public speakers of his day[9] and, according to Bryson, "more than a thousand people crowded into the chamber; hundreds more were turned away."[10] Darwin himself was too sick to attend.[6]

The discussion was chaired by John Stevens Henslow, Darwin's former mentor from Cambridge. It has been suggested that Owen arranged for Henslow to chair the discussion "hoping to make the expected defeat of Darwin the more complete".[6] The main focus of the meeting was supposed to be a lecture by New York University's John William Draper, "On the Intellectual Development of Europe, considered with reference to the views of Mr. Darwin and others, that the progression of organisms is determined by law".[6] By all accounts, Draper's presentation was long and boring.[6][10] After Draper had finished, Henslow called on several other speakers, including Benjamin Brodie, the President of the Royal Society, before it was Wilberforce's turn.[6]

In a letter to his brother Edward, the ornithologist Alfred Newton wrote:

In the Nat. Hist. Section we had another hot Darwinian debate ... After [lengthy preliminaries] Huxley was called upon by Henslow to state his views at greater length, and this brought up the Bp. of Oxford ... Referring to what Huxley had said two days before, about after all its not signifying to him whether he was descended from a Gorilla or not, the Bp. chafed him and asked whether he had a preference for the descent being on the father's side or the mother's side? This gave Huxley the opportunity of saying that he would sooner claim kindred with an Ape than with a man like the Bp. who made so ill a use of his wonderful speaking powers to try and burke, by a display of authority, a free discussion on what was, or was not, a matter of truth, and reminded him that on questions of physical science 'authority' had always been bowled out by investigation, as witness astronomy and geology. A lot of people afterwards spoke ... the feeling of the meeting was very much against the Bp.[11]

According to Lucas, "Wilberforce, contrary to the central tenet of the legend, did not prejudge the issue",[12] but he is in a minority on this, as Jensen makes clear.[13] Wilberforce criticised Darwin's theory on ostensibly scientific grounds, arguing that it was not supported by the facts, and he noted that the greatest names in science were opposed to the theory.[12] Nonetheless, Wilberforce's speech is generally only remembered today for his inquiry as to whether it was through his grandmother or his grandfather that Huxley considered himself descended from a monkey.

According to a letter written 30 years later to Francis Darwin,[14] when Huxley heard this he whispered to Brodie, "The Lord hath delivered him into mine hands".[15] This quotation first appears more than thirty years later, and is almost certainly a later insertion to the story. Huxley's own contemporary account, in a letter to Henry Dyster on September 9, 1860, makes no mention of this remark. Huxley rose to defend Darwin's theory, finishing his speech with the now-legendary assertion that he was not ashamed to have a monkey for his ancestor, but he would be ashamed to be connected with a man who used great gifts to obscure the truth.[12] Again, later retellings indicate that this had a tremendous effect on the audience, and Lady Brewster is said to have fainted.[6]

More reliable accounts indicate that although Huxley did respond with the "monkey" retort, the remainder of his speech was unremarkable. Balfour Stewart, a prominent scientist and director of the Kew Observatory, wrote afterward that, "I think the Bishop had the best of it."[16] Joseph Dalton Hooker, Darwin's friend and botanical mentor, noted in a letter to Darwin that Huxley had been largely inaudible in the hall:

Well, Sam Oxon got up and spouted for half an hour with inimitable spirit, ugliness and emptiness and unfairness ... Huxley answered admirably and turned the tables, but he could not throw his voice over so large an assembly nor command the audience ... he did not allude to Sam's weak points nor put the matter in a form or way that carried the audience.[17]

It is likely that the main point is accurate, that Huxley was not effective in speaking to the large audience. He was not yet an accomplished speaker and wrote afterward that he had been inspired as to the value of oration by what he witnessed in that meeting.

Next, Henslow called upon Admiral Robert FitzRoy, who had been Darwin's captain and companion on the voyage of the Beagle twenty-five years earlier. FitzRoy denounced Darwin's book and, "lifting an immense Bible first with both hands and afterwards with one hand over his head, solemnly implored the audience to believe God rather than man". He was believed to have said: "I believe that this is the Truth, and had I known then what I know now, I would not have taken him [Darwin] aboard the Beagle."[18]

The last speaker of the day was Hooker. According to his own account, it was he and not Huxley who delivered the most effective reply to Wilberforce's arguments: "Sam was shut up—had not one word to say in reply, and the meeting was dissolved forthwith"[19] Ruse claims that "everybody enjoyed himself immensely and all went cheerfully off to dinner together afterwards".[20]

It is said that during the debate, two Cambridge dons happened to be standing near Wilberforce, one of whom was Henry Fawcett, the recently blinded economist. Fawcett was asked whether he thought the bishop had actually read the Origin of Species. "Oh no, I would swear he has never read a word of it", Fawcett reportedly replied loudly. Wilberforce swung round to him scowling, ready to recriminate, but stepped back and bit his tongue on noting that the protagonist was the blind economist. (See p. 126 of Janet Browne (2003) Charles Darwin: The Power of Place.)

Notably, all three major participants felt they had had the best of the debate. Wilberforce wrote that, "On Saturday Professor Henslow ... called on me by name to address the Section on Darwin's theory. So I could not escape and had quite a long fight with Huxley. I think I thoroughly beat him."[21] Huxley claimed "[I was] the most popular man in Oxford for a full four & twenty hours afterwards." Hooker wrote that "I have been congratulated and thanked by the blackest coats and whitest stocks in Oxford."[6] Wilberforce and Darwin remained on good terms after the debate.

3. Legacy

Summary reports of the debate were published in The Manchester Guardian, The Athenaeum and Jackson's Oxford Journal.[6] A more detailed report was published by the Oxford Chronicle.[22] Both sides immediately claimed victory, but the majority opinion has always been that the debate represented a major victory for the Darwinians.[13]

Though the debate is frequently depicted as a clash between religion and science, the British Association at the time had a number of clergymen occupying high positions (including Presidents of two of its seven sections)[23] In his speech to open the annual event, the President of the Association (Lord Wrottesley) concluded his talk by saying "Let us ever apply ourselves to the task, feeling assured that the more we thus exercise, and by exercising improve our intellectual faculties, the more worthy shall we be, the better shall we be fitted to come nearer to our God."[24] Therefore, a case could be made for saying that for the many clerics in the audience, the underlying conflict was between traditional Anglicanism (Wilberforce) and liberal Anglicanism (Essays and Reviews). On the other hand, Oxford academic Dr Diane Purkiss says the debate "was really the first time Christianity had ever been asked to square off against science in a public forum in the whole of its history".[14]

Many of the opponents of Darwin's theory were respected men of science: Owen was one of the most influential British biologists of his generation; Adam Sedgwick was a leading geologist; Wilberforce was a Fellow of the Royal Society (though at that time about half of the Fellows were well-placed amateurs). While Darwin himself was a gentleman scholar of independent financial means, key disciples like Huxley and Hooker were professionals, and they concentrated on the advance of scientific knowledge, and were determined not to be baulked by religious authority. Their kind of science was to grow and flourish, and ultimately to become autonomous from religious tradition.

The debate has been called "one of the great stories of the history of science"[8] and it is often regarded as a key moment in the acceptance of evolution. However, at the time it received only a few passing references in newspapers,[25] and Brooke argues that "the event almost completely disappeared from public awareness until it was resurrected in the 1890s as an appropriate tribute to a recently deceased hero of scientific education".[8] Note also that the contemporary accounts of the participants were largely replaced by a somewhat embellished version (see the much later insertion of Huxley's remark to Brodie, for example). The great popularity of the anecdote in the 20th century was largely due to shifting attitudes towards evolution and anachronistic re-interpretation of the actual events.

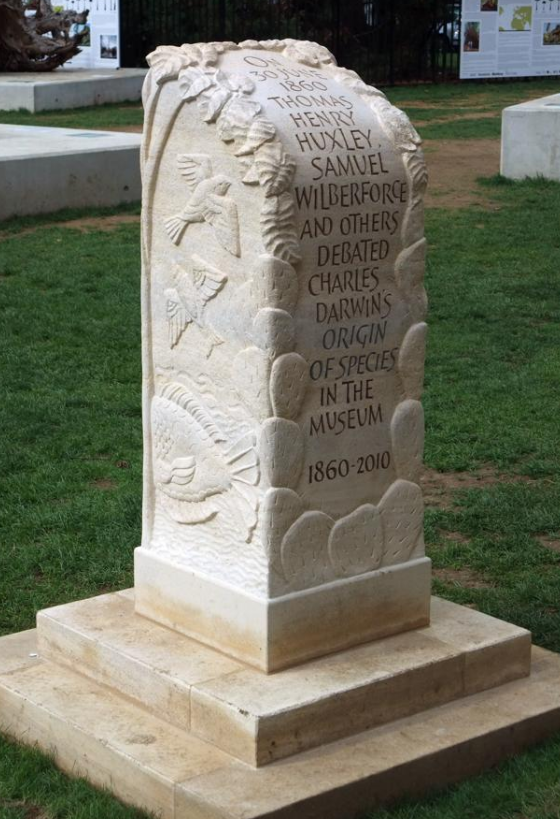

The debate marked the beginning of a bitter three-year dispute between Owen and Huxley over human origins, satirised by Charles Kingsley as the "Great Hippocampus Question", which concluded with the defeat of Owen and his backers.[7] The debate was the inspiration for, and is referenced in, the play Darwin in Malibu by Crispin Whittell. A commemorative pillar marks the 150th anniversary of the debate.[14]

References

- Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1991). Darwin. London: Michael Joseph, Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-7181-3430-3.

- Owen, Richard (1860). "Review of Darwin's Origin of Species". Edinburgh Review 3 (April 1860): 487–532. Archived from the original on 6 August 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100806060548/http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=A30&viewtype=text&pageseq=1. . Published anonymously.

- Wilberforce, Samuel (1860). "(Review of) On the Origin of Species". Quarterly Review 108 (215): 225–264. Archived from the original on 6 August 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100806051419/http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=A19&viewtype=text&pageseq=1. . Published anonymously.

- Huxley, Thomas Henry (1893–94). Collected essays: vol 2 Darwiniana. London: Macmillan. pp. 1–20.

- Foster, Michael; Lankester, E. Ray (2007). The scientific memoirs of Thomas Henry Huxley. 4 vols and supplement. London: Macmillan (published 1898–1903). p. 400. ISBN 978-1-4326-4011-8.

- Thomson, Keith Stewart (2000). "Huxley, Wilberforce and the Oxford Museum". American Scientist 88 (3): 210. doi:10.1511/2000.3.210. http://www.americanscientist.org/issues/pub/2000/5/huxley-wilberforce-and-the-oxford-museum.

- Gross, Charles G. (1993). "Hippocampus minor and man's place in nature: a case study in the social construction of neuroanatomy". Hippocampus 3 (4): 407–413. doi:10.1002/hipo.450030403. PMID 8269033. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fhipo.450030403

- Brooke, John Hedley (2001). "Darwinism & Religion: a Revisionist View of the Wilberforce-Huxley Debate". Lecture delivered at Emmanuel College, Cambridge on 26 February 2001. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20081211074654/http://www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk/cis/brooke/. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- Natural History Museum. Samuel Wilberforce. Retrieved on 1 June 2011. http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/evolution/how-did-evol-theory-develop/evol-samuel-wilberforce/index.html

- Bryson, Bill (2003). A Short History of Nearly Everything. London: Doubleday. pp. 348–349. ISBN 978-0-7679-0817-7.

- Wollaston, A. F. R. (1921). Life of Alfred Newton: late Professor of Comparative Anatomy, Cambridge University 1866–1907, with a Preface by Sir Archibald Geikie OM. New York: Dutton. pp. 118–120.

- Lucas, J. R. (1979). "Wilberforce and Huxley: a legendary encounter". The Historical Journal 22 (2): 313–330. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00016848. PMID 11617072. http://users.ox.ac.uk/~jrlucas/legend.html.

- Jensen, J. Vernon (1991). ""Debate" with Bishop Wilberforce, 1860". Thomas Henry Huxley: communicating for science. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses. pp. 63–86. ISBN 978-0-87413-379-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=GINeLJUueCoC&pg=PA63. [This chapter is an excellent survey, and its notes gives references to all the eyewitness accounts except Newton. The great majority of these accounts do accord with the traditional version.]

- Flood, Alison (10 September 2010). "Plinth commemorates Huxley-Wilberforce evolution debate". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/sep/10/plinth-huxley-wilberforce-evolution-debate. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- Huxley, Leonard (1900). The Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley. 1. London: Macmillan. p. 202.

- Balfour Stewart, letter to David Forbes, July 4, 1860.

- "Letter 2852 — Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., 2 July 1860". Darwin Correspondence Project. http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-2852. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- Green, Vivian H. H. (1996). A New History of Christianity. New York: Continuum. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8264-1227-0.

- Huxley L. 1918. Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM, GCSI. 2 vols, I pp. 522–525 (letter to Darwin, July 2nd 1860).

- Ruse, Michael (2001). Can a Darwinian be a Christian? The Relationship between Science and Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-63716-9. https://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambridge%20University%20Press

- Samuel Wilberforce, letter to Sir Charles Anderson, July 3, 1860.

- England, Richard (June 28, 2017). "Censoring Huxley and Wilberforce: A new source for the meeting that the Athenaeum 'wisely softened down'". Notes and Records 71 (4): 20160058. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2016.0058. ISSN 0035-9149. https://dx.doi.org/10.1098%2Frsnr.2016.0058

- Jackson's Oxford Journal, 23 June 1860.

- Jackson's Oxford Journal, 30 June 1860.

- E.g., Liverpool Mercury, 5 July 1860.