| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beatrix Zheng | -- | 2564 | 2022-10-18 01:33:03 |

Video Upload Options

The Schwarzschild solution describes spacetime under the influence of a massive, non-rotating, spherically symmetric object. It is considered by some to be one of the simplest and most useful solutions to the Einstein field equations.

1. Assumptions and Notation

Working in a coordinate chart with coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ \left(r, \theta, \phi, t \right) }[/math] labelled 1 to 4 respectively, we begin with the metric in its most general form (10 independent components, each of which is a smooth function of 4 variables). The solution is assumed to be spherically symmetric, static and vacuum. For the purposes of this article, these assumptions may be stated as follows (see the relevant links for precise definitions):

- A spherically symmetric spacetime is one that is invariant under rotations and taking the mirror image.

- A static spacetime is one in which all metric components are independent of the time coordinate [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] (so that [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac\partial{\partial t}g_{\mu \nu}=0 }[/math]) and the geometry of the spacetime is unchanged under a time-reversal [math]\displaystyle{ t \rightarrow -t }[/math].

- A vacuum solution is one that satisfies the equation [math]\displaystyle{ T_{ab}=0 }[/math]. From the Einstein field equations (with zero cosmological constant), this implies that [math]\displaystyle{ R_{ab}=0 }[/math] since contracting [math]\displaystyle{ R_{ab}-\tfrac{R}{2} g_{ab}=0 }[/math] yields [math]\displaystyle{ R = 0 }[/math].

- Metric signature used here is (+,+,+,−).

2. Diagonalising the Metric

The first simplification to be made is to diagonalise the metric. Under the coordinate transformation, [math]\displaystyle{ (r, \theta, \phi, t) \rightarrow (r, \theta, \phi, -t) }[/math], all metric components should remain the same. The metric components [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\mu 4} }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ \mu \ne 4 }[/math]) change under this transformation as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\mu 4}'=\frac{\partial x^{\alpha}}{\partial x^{'\mu}} \frac{\partial x^{\beta}}{\partial x^{'4}} g_{\alpha \beta}= -g_{\mu 4} }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ \mu \ne 4 }[/math])

But, as we expect [math]\displaystyle{ g'_{\mu 4}= g_{\mu 4} }[/math] (metric components remain the same), this means that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\mu 4}=\, 0 }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ \mu \ne 4 }[/math])

Similarly, the coordinate transformations [math]\displaystyle{ (r, \theta, \phi, t) \rightarrow (r, \theta, -\phi, t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (r, \theta, \phi, t) \rightarrow (r, -\theta, \phi, t) }[/math] respectively give:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\mu 3}=\, 0 }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ \mu \ne 3 }[/math])

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\mu 2}=\, 0 }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ \mu \ne 2 }[/math])

Putting all these together gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\mu \nu }=\, 0 }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ \mu \ne \nu }[/math])

and hence the metric must be of the form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ ds^2=\, g_{11}\,d r^2 + g_{22} \,d \theta ^2 + g_{33} \,d \phi ^2 + g_{44} \,dt ^2 }[/math]

where the four metric components are independent of the time coordinate [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] (by the static assumption).

3. Simplifying the Components

On each hypersurface of constant [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math], constant [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] and constant [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] (i.e., on each radial line), [math]\displaystyle{ g_{11} }[/math] should only depend on [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] (by spherical symmetry). Hence [math]\displaystyle{ g_{11} }[/math] is a function of a single variable:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{11}=A\left(r\right) }[/math]

A similar argument applied to [math]\displaystyle{ g_{44} }[/math] shows that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{44}=B\left(r\right) }[/math]

On the hypersurfaces of constant [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] and constant [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math], it is required that the metric be that of a 2-sphere:

- [math]\displaystyle{ dl^2=r_{0}^2 (d \theta^2 + \sin^2 \theta\, d \phi^2) }[/math]

Choosing one of these hypersurfaces (the one with radius [math]\displaystyle{ r_{0} }[/math], say), the metric components restricted to this hypersurface (which we denote by [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{g}_{22} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{g}_{33} }[/math]) should be unchanged under rotations through [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] (again, by spherical symmetry). Comparing the forms of the metric on this hypersurface gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{g}_{22}\left(d \theta^2 + \frac{\tilde{g}_{33}}{\tilde{g}_{22}} \,d \phi^2 \right) = r_{0}^2 (d \theta^2 + \sin^2 \theta \,d \phi^2) }[/math]

which immediately yields:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{g}_{22}=r_{0}^2 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{g}_{33}=r_{0}^2 \sin ^2 \theta }[/math]

But this is required to hold on each hypersurface; hence,

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{22}=\, r^2 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ g_{33}=\, r^2 \sin^2 \theta }[/math]

An alternative intuitive way to see that [math]\displaystyle{ g_{22} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ g_{33} }[/math] must be the same as for a flat spacetime is that stretching or compressing an elastic material in a spherically symmetric manner (radially) will not change the angular distance between two points.

Thus, the metric can be put in the form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ ds^2=A\left(r\right)dr^2+r^2\,d \theta^2+r^2 \sin^2 \theta \,d \phi^2 + B\left(r\right) dt^2 }[/math]

with [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] as yet undetermined functions of [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math]. Note that if [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is equal to zero at some point, the metric would be singular at that point.

4. Calculating the Christoffel Symbols

Using the metric above, we find the Christoffel symbols, where the indices are [math]\displaystyle{ (1,2,3,4)=(r,\theta,\phi,t) }[/math]. The sign [math]\displaystyle{ ' }[/math] denotes a total derivative of a function.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma^1_{ik} = \begin{bmatrix} A'/\left( 2A \right) & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & -r/A & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & -r \sin^2 \theta /A & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -B'/\left( 2A \right) \end{bmatrix} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma^2_{ik} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1/r & 0 & 0\\ 1/r & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & -\sin\theta\cos\theta & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma^3_{ik} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1/r & 0\\ 0 & 0 & \cot\theta & 0\\ 1/r & \cot\theta & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma^4_{ik} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & B'/\left( 2B \right)\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ B'/\left( 2B \right) & 0 & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix} }[/math]

5. Using the Field Equations to Find A(r) and B(r)

To determine [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math], the vacuum field equations are employed:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_{\alpha\beta}=\, 0 }[/math]

Hence:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\Gamma^\rho_{\beta\alpha,\rho}} - \Gamma^\rho_{\rho\alpha,\beta} + \Gamma^\rho_{\rho\lambda} \Gamma^\lambda_{\beta\alpha} - \Gamma^\rho_{\beta\lambda}\Gamma^\lambda_{\rho\alpha}=0\,, }[/math]

where a comma is used to set off the index that is being used for the derivative. Only three of these equations are nontrivial and upon simplification become:

- [math]\displaystyle{ 4 A' B^2 - 2 r B'' AB + r A' B'B + r B' ^2 A=0\,, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ r A'B + 2 A^2 B - 2AB - r B' A=0\,, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ - 2 r B'' AB + r A' B'B + r B' ^2 A - 4B' AB=0 }[/math]

(the fourth equation is just [math]\displaystyle{ \sin^2 \theta }[/math] times the second equation), where the prime means the r derivative of the functions. Subtracting the first and third equations produces:

- [math]\displaystyle{ A'B +A B'=0 \Rightarrow A(r)B(r) =K }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is a non-zero real constant. Substituting [math]\displaystyle{ A(r)B(r) \, =K }[/math] into the second equation and tidying up gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ r A' =A(1-A) }[/math]

which has general solution:

- [math]\displaystyle{ A(r)=\left(1+\frac{1}{Sr}\right)^{-1} }[/math]

for some non-zero real constant [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]. Hence, the metric for a static, spherically symmetric vacuum solution is now of the form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ ds^2=\left(1+\frac{1}{S r}\right)^{-1}dr^2+r^2(d \theta^2 + \sin^2 \theta d \phi^2)+K \left(1+\frac{1}{S r}\right)dt^2 }[/math]

Note that the spacetime represented by the above metric is asymptotically flat, i.e. as [math]\displaystyle{ r \rightarrow \infty }[/math], the metric approaches that of the Minkowski metric and the spacetime manifold resembles that of Minkowski space.

6. Using the Weak-field Approximation to Find K and S

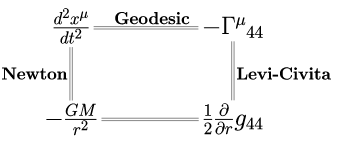

The geodesics of the metric (obtained where [math]\displaystyle{ ds }[/math] is extremised) must, in some limit (e.g., toward infinite speed of light), agree with the solutions of Newtonian motion (e.g., obtained by Lagrange equations). (The metric must also limit to Minkowski space when the mass it represents vanishes.)

- [math]\displaystyle{ 0=\delta\int\frac{ds}{dt}dt=\delta\int(KE+PE_g)dt }[/math]

(where [math]\displaystyle{ KE }[/math] is the kinetic energy and [math]\displaystyle{ PE_g }[/math] is the Potential Energy due to gravity) The constants [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] are fully determined by some variant of this approach; from the weak-field approximation one arrives at the result:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{44}=K\left(1 +\frac{1}{Sr}\right) \approx -c^2+\frac{2Gm}{r} = -c^2 \left(1-\frac{2Gm}{c^2 r} \right) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] is the gravitational constant, [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is the mass of the gravitational source and [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] is the speed of light. It is found that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ K=\, -c^2 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{S}=-\frac{2Gm}{c^2} }[/math]

Hence:

- [math]\displaystyle{ A(r)=\left(1-\frac{2Gm}{c^2 r}\right)^{-1} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B(r)=-c^2 \left(1-\frac{2Gm}{c^2 r}\right) }[/math]

So, the Schwarzschild metric may finally be written in the form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ ds^2=\left(1-\frac{2Gm}{c^2 r}\right)^{-1}dr^2+r^2(d \theta^2 +\sin^2 \theta d \phi^2)-c^2 \left(1-\frac{2Gm}{c^2 r}\right)dt^2 }[/math]

Note that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{2Gm}{c^2}=r_s }[/math]

is the definition of the Schwarzschild radius for an object of mass [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math], so the Schwarzschild metric may be rewritten in the alternative form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ ds^2=\left(1-\frac{r_s}{r}\right)^{-1}dr^2+r^2(d\theta^2 +\sin^2\theta d\phi^2)-c^2\left(1-\frac{r_s}{r}\right)dt^2 }[/math]

which shows that the metric becomes singular approaching the event horizon (that is, [math]\displaystyle{ r \rightarrow r_s }[/math]). The metric singularity is not a physical one (although there is a real physical singularity at [math]\displaystyle{ r=0 }[/math]), as can be shown by using a suitable coordinate transformation (e.g. the Kruskal–Szekeres coordinate system).

7. Alternate Derivation Using Known Physics in Special Cases

The Schwarzschild metric can also be derived using the known physics for a circular orbit and a temporarily stationary point mass.[1] Start with the metric with coefficients that are unknown coefficients of [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ -c^2 = \left ( {ds \over d\tau} \right )^2 = A(r)\left ( {dr \over d\tau} \right )^2 + r^2\left ( {d\phi \over d\tau} \right )^2 + B(r)\left( {dt \over d\tau} \right)^2. }[/math]

Now apply the Euler-Lagrange equation to the arc length integral [math]\displaystyle{ { J=\int_{\tau_1}^{\tau_2} \sqrt{-\left(\text{d}s/\text{d}\tau\right)^2 }\, \text{d}\tau. } }[/math] Since [math]\displaystyle{ ds/d\tau }[/math] is constant, the integrand can be replaced with [math]\displaystyle{ (\text{d}s/\text{d}\tau)^2, }[/math] because the E-L equation is exactly the same if the integrand is multiplied by any constant. Applying the E-L equation to [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] with the modified integrand yields:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{lcl} A'(r)\dot{r}^2 + 2r\dot{\phi}^2 + B'(r)\dot{t}^2 & = & 2A'(r)\dot{r}^2 + 2A(r)\ddot{r} \\ 0 & = & 2r\dot{r}\dot{\phi} + r^2\ddot{\phi} \\ 0 & = & B'(r)\dot{r}\dot{t} + B(r)\ddot{t} \end{array} }[/math]

where dot denotes differentiation with respect to [math]\displaystyle{ \tau. }[/math]

In a circular orbit [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{r}=\ddot{r}=0, }[/math] so the first E-L equation above is equivalent to

- [math]\displaystyle{ 2r\dot{\phi}^2 + B'(r)\dot{t}^2 = 0 \Leftrightarrow B'(r) = -2r\dot{\phi}^2/\dot{t}^2 = -2r(d\phi/dt)^2. }[/math]

Kepler's third law of motion is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{T^2}{r^3} = \frac{4\pi^2}{G(M+m)}. }[/math]

In a circular orbit, the period [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] equals [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi / (d\phi/dt), }[/math] implying

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left( {d\phi \over dt} \right)^2 = GM/r^3 }[/math]

since the point mass [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is negligible compared to the mass of the central body [math]\displaystyle{ M. }[/math] So [math]\displaystyle{ B'(r) = -2GM/r^2 }[/math] and integrating this yields [math]\displaystyle{ B(r) = 2GM/r + C, }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is an unknown constant of integration. [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] can be determined by setting [math]\displaystyle{ M=0, }[/math] in which case the space-time is flat and [math]\displaystyle{ B(r)=-c^2. }[/math] So [math]\displaystyle{ C = -c^2 }[/math] and

- [math]\displaystyle{ B(r) = 2GM/r - c^2 = c^2(2GM/c^2/r - 1) = c^2(r_s/r - 1). }[/math]

When the point mass is temporarily stationary, [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{r}=0 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{\phi}=0. }[/math] The original metric equation becomes [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{t}^2 = -c^2/B(r) }[/math] and the first E-L equation above becomes [math]\displaystyle{ A(r) = B'(r)\dot{t}^2 / (2\ddot{r}). }[/math] When the point mass is temporarily stationary, [math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{r} }[/math] is the acceleration of gravity, [math]\displaystyle{ -MG/r^2. }[/math] So

- [math]\displaystyle{ A(r) = \left(\frac{-2MG}{r^2}\right) \left(\frac{-c^2}{2MG/r - c^2}\right) \left(-\frac{r^2}{2MG}\right) = \frac{1}{1 - 2MG/(rc^2)} = \frac{1}{1 - r_s/r}. }[/math]

8. Alternative Form in Isotropic Coordinates

The original formulation of the metric uses anisotropic coordinates in which the velocity of light is not the same in the radial and transverse directions. Arthur Eddington gave alternative forms in isotropic coordinates.[2] For isotropic spherical coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ r_1 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math], coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] are unchanged, and then (provided [math]\displaystyle{ r \geq \frac{2 Gm}{c^2} }[/math])[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ r = r_1 \left(1+\frac{Gm}{2c^2 r_1}\right)^{2} }[/math] , [math]\displaystyle{ dr = dr_1 \left(1-\frac{(Gm)^2}{4c^4 r_1^2}\right) }[/math] , and

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(1-\frac{2Gm}{c^2 r}\right) = \left(1-\frac{Gm}{2c^2 r_1}\right)^{2}/\left(1+\frac{Gm}{2c^2 r_1}\right)^{2} }[/math]

Then for isotropic rectangular coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ x = r_1\, \sin(\theta)\, \cos(\phi) \quad, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ y = r_1\, \sin(\theta)\, \sin(\phi) \quad, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ z = r_1\, \cos(\theta) }[/math]

The metric then becomes, in isotropic rectangular coordinates:

- [math]\displaystyle{ ds^2= \left(1+\frac{Gm}{2c^2 r_1}\right)^{4}(dx^2+dy^2+dz^2) -c^2 dt^2 \left(1-\frac{Gm}{2c^2 r_1}\right)^{2}/\left(1+\frac{Gm}{2c^2 r_1}\right)^{2} }[/math]

9. Dispensing with the Static Assumption - Birkhoff's Theorem

In deriving the Schwarzschild metric, it was assumed that the metric was vacuum, spherically symmetric and static. In fact, the static assumption is stronger than required, as Birkhoff's theorem states that any spherically symmetric vacuum solution of Einstein's field equations is stationary; then one obtains the Schwarzschild solution. Birkhoff's theorem has the consequence that any pulsating star which remains spherically symmetric cannot generate gravitational waves (as the region exterior to the star must remain static).

References

- Brown, Kevin. "Reflections on Relativity". http://www.mathpages.com/rr/s5-05/5-05.htm.

- A S Eddington, "Mathematical Theory of Relativity", Cambridge UP 1922 (2nd ed.1924, repr.1960), at page 85 and page 93. Symbol usage in the Eddington source for interval s and time-like coordinate t has been converted for compatibility with the usage in the derivation above. https://books.google.com/books?id=Hhg0AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA93

- Buchdahl, H. A. (1985). "Isotropic coordinates and Schwarzschild metric". International Journal of Theoretical Physics 24 (7): 731–739. doi:10.1007/BF00670880. Bibcode: 1985IJTP...24..731B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF00670880