Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | George Laliotis | -- | 2303 | 2022-10-17 12:13:12 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 3 word(s) | 2306 | 2022-10-18 03:56:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Lin, P.H.; Laliotis, G. Current Treatment Options of Metastatic Breast Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/29699 (accessed on 03 March 2026).

Lin PH, Laliotis G. Current Treatment Options of Metastatic Breast Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/29699. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Lin, Pauline H., George Laliotis. "Current Treatment Options of Metastatic Breast Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/29699 (accessed March 03, 2026).

Lin, P.H., & Laliotis, G. (2022, October 17). Current Treatment Options of Metastatic Breast Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/29699

Lin, Pauline H. and George Laliotis. "Current Treatment Options of Metastatic Breast Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 October, 2022.

Copy Citation

breast cancer subtypes and classifications are well-characterized and personalized for each patient group. To this extent, given the distinct classification of breast cancer, the therapeutic decision and algorithms of metastatic disease is largely dependent on its molecular subclassification and on HR and HER-2 expression status.

breast

cancer

metastasis

oncology

1. Treatment of Hormone Receptor Positive mBC

The treatment of HR+ mBC is defined by numerous clinical factors. These factors include the menopausal status (pre- or post-) at the time of metastatic disease, the recurrence of metastatic disease, the time interval between each recurrence episode, the status of specific concurrent mutations (e.g., PIK3CA and BRCA mutations), the presence of bone or visceral metastatic disease and the overall performance status. It is also worth mentioning that in clinical practice, de novo metastatic disease, recurrence after more than 12 months of adjuvant therapy and bone metastasis, fall into the endocrine-sensitive subgroups of patients [1]. Lastly, it is important to note that clinicians should obtain clinical tumor samples at baseline and at the treatment naive stage, since the therapeutic decisions depend on Next Generation Sequencing, transcriptomic and mutational characteristics of the tumor. This allows the researchers to compare the biological development of the early stage versus the metastatic tumor, to better guide clinical decisions [2].

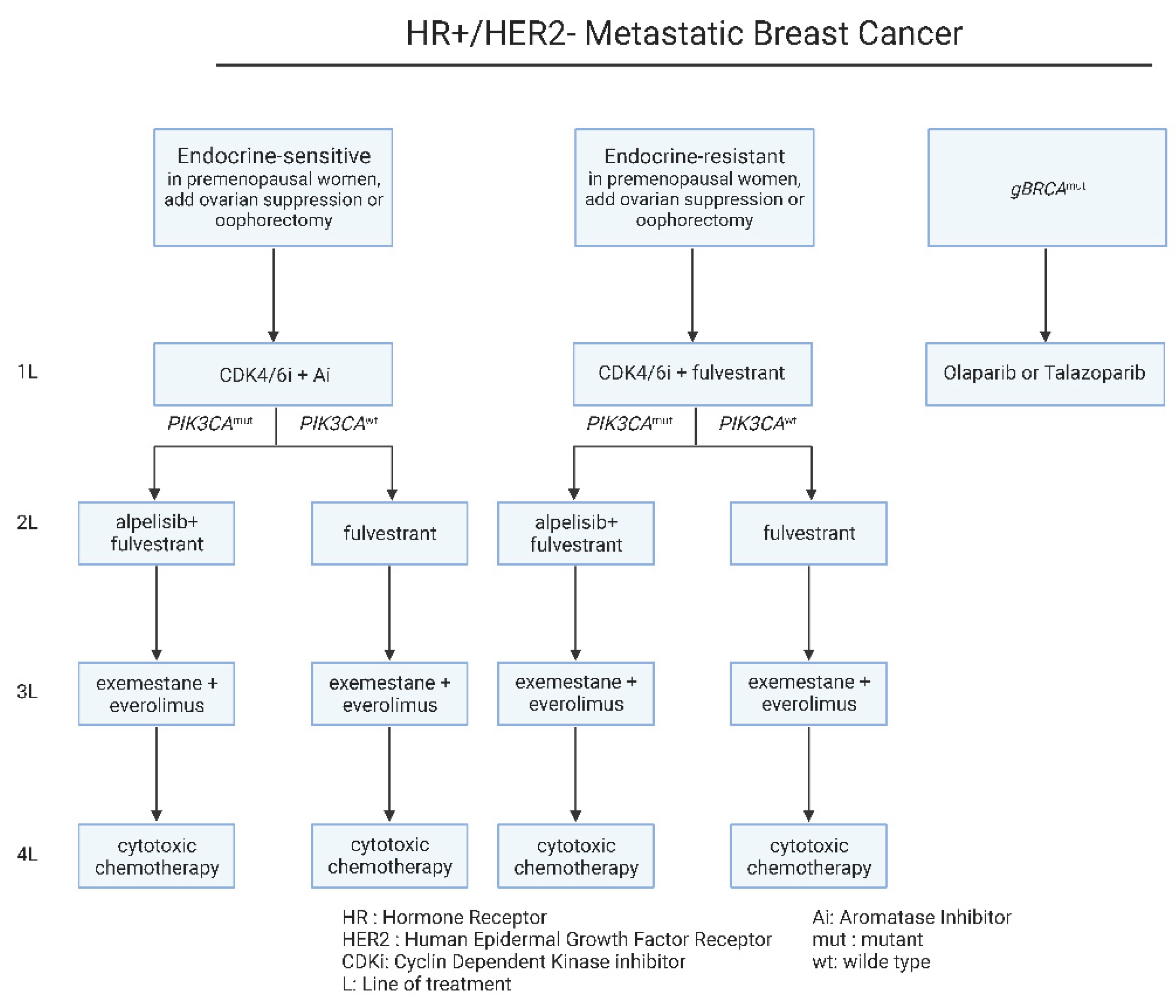

The main clinical first line recommendation depends on the recurrence time interval and the menopausal status (Figure 1). In estrogen-sensitive cases, the administration of CDK4/6 with an aromatase inhibitor, should be considered the standard-of-care option in these patients [3][4]. CDK4/6 inhibitors have been approved more than 6 years ago for metastatic ER+ metastatic disease, based on the findings of PALOMA-1 trial [4]. Furthermore, the combination of CDK4/6i, ribociclib plus estrogen therapy significantly improved overall survival (OS) relative to estrogen therapy alone, according to the important phase III MONALEESA-2, MONALEESA-3, and MONALEESA-7 trials [5]. On the other hand, regarding the estrogen-resistant cases or in cases with no suitability for aromatase inhibitors, CDK4/6 inhibitors should be combined with fulvestrant, an estrogen degrader [6][7][8].

Figure 1. Current therapeutic algorithm for the management of HR+/HER-2− mBC. Proposed therapeutic algorithm for patients with HR+/HER-2− metastatic breast cancer [9]. The abbreviations of the terms used in the figure are outlined in the lower part of the algorithm.

Following disease progression upon first-line treatment, in the case of the estrogen-resistant groups, PIK3CA mutational status defines the therapeutic decisions. In patients harboring PIK3CA mutations, fulvestrant can be combined with alpelisib, a PIK3α specific inhibitor [10]. Alpelisib has been approved as a combination therapy with fulvestrant for PIK3CA mutated ER+/HER-2− metastatic breast cancer, upon the findings of SOLAR-1 clinical trial [11]. On the other hand, the estrogen-sensitive patients with recurrence on CDK4/6 inhibitors, can be treated with an aromatase inhibitor in combination with the mTOR inhibitor, everolimus [10] (Figure 1). Beyond these therapeutic strategies, subsequent lines of therapy include cytotoxic chemotherapy for all patients [12][13][14] (Figure 1). On a different note, the administration of the same chemotherapeutic regimen upon recurrence, is not recommended, with the exemption of taxanes that can be used upon early and metastatic disease [1][12][13].

2. Treatment of HER-2 Positive mBC

Traditionally, the HER-2+ breast cancer has been a more aggressive clinical subtype compared to the HR+ subtype, with poorer clinical outcomes [15][16]. Nevertheless, due to advancements in drug development and introduction of HER-2 targeting therapies, such as trastuzumab and trastuzumab-emtansine (T-DM1), the median survival of these patients has been increased to 5 years, and up to 8 years in 30–40% of the cases [16][17].

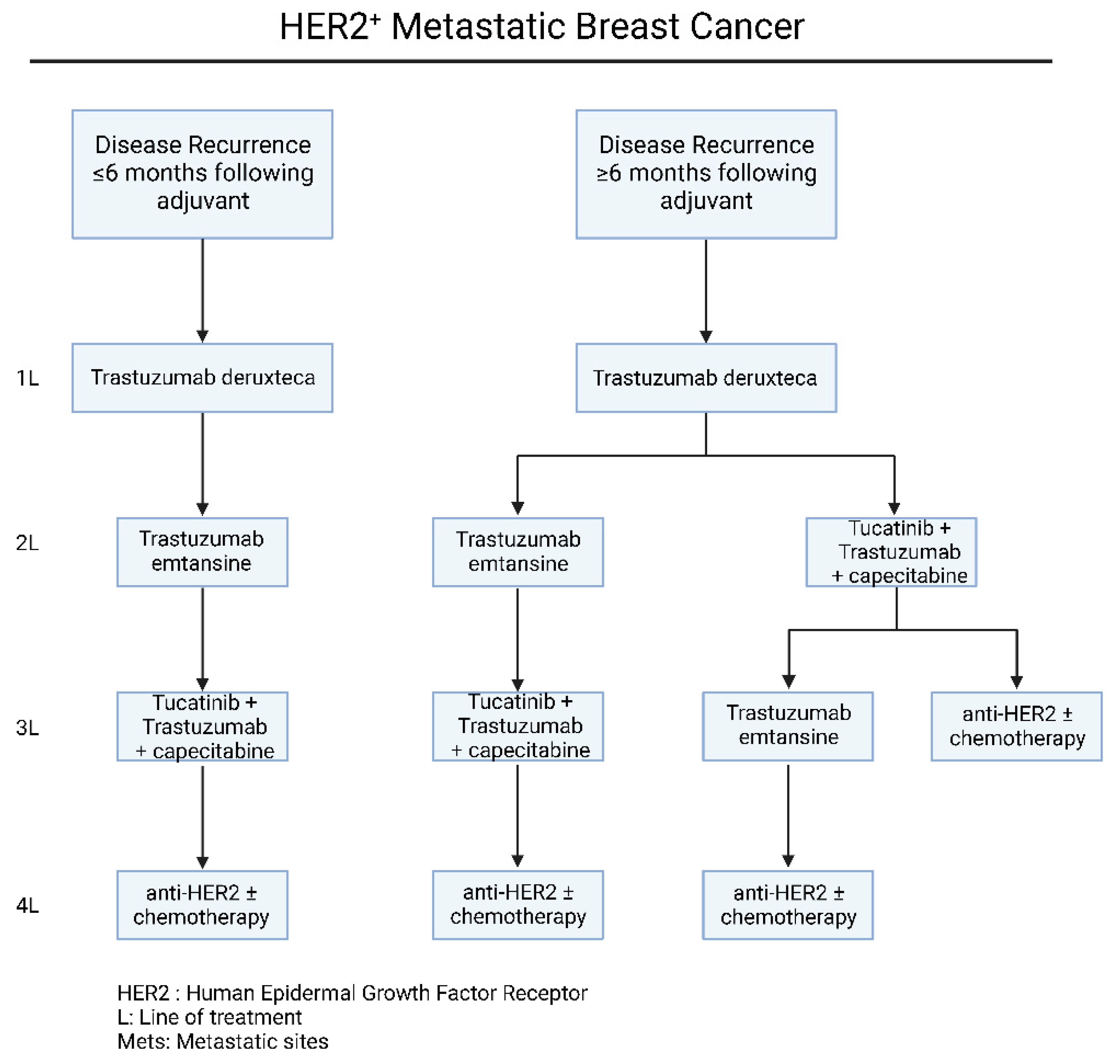

As far as the therapeutic strategies of HER-2+ metastatic breast cancer are concerned, the main clinical factor that determines the first-line therapy option is the time of recurrence after adjuvant therapy (Figure 2). To begin with, based on recent guidelines and experts’ opinion, the combination of trastuzumab and pertuzumab with a single chemotherapeutic reagent, should be considered as the first-line of treatment in patients with recurrence after 6 months of adjuvant treatment [18] (Figure 2). The usage of pertuzumab with the widely used trastuzumab, has been validated through the large phase III CLEOPARTA trial, which compared the addition of pertuzumab versus placebo, in HER-2+ mBC patients that have received trastuzumab, and docetaxel [19][20]. Specifically for CLEOPATRA trial, the OS in the pertuzumab receiving group was 56.5 months (95% CI, 49.3 to not reached), compared to 40.8 months (95% CI, 35.8 to 48.3) in the group receiving the placebo combination (HR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.84; p < 0.001) [19][20]. The therapeutic regimen of pertuzumab, is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the dimerization of HER-2 by binding the extracellular domain II of the protein [21]. Due to its targeting of HER-2, the trastuzumab-pertuzumab combination provides a multi-level inhibition against these tumors, radically increasing therapeutic responses [22][23][24].

Figure 2. Current therapeutic algorithm for the management of HER-2+ mBC. Proposed therapeutic algorithm for patients with HER-2+ metastatic breast cancer [16]. The abbreviations of the terms used in the figure are outlined in the lower part of the algorithm.

For patients that were presented with a recurrence in less than 6 months or progressed on trastuzumab and/or pertuzumab-based chemotherapy, the administration of T-DM1 should be considered as the second-line of choice (Figure 2). The FDA-approved T-DM1 regiment consists of the anti-HER-2 antibody trastuzumab, stably linked with microtubule-inhibitory agent DM1, in a 1:3.5 ratio [25][26]. This chemical structure allows specific drug delivery to HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells intracellularly. The efficacy and safety profiling of T-DM1, is based on the results of EMILIA [25] and TH3RESA [26][27] phase III clinical trials, which compared T-DM1 with lapatinib plus capecitabine or chemotherapy plus trastuzumab, respectively.

Beyond targeted anti-HER-2 therapies, there are several drug regimens that have been FDA approved for patients that have progressed upon trastuzumab, pertuzumab and T-DM1. Nevertheless, there is no definite clinical algorithm for the management of these patients and the optimal sequence of drug administration remains largely unclear, depending mainly on the clinical characteristics, site of progression and toxicity profile. As far as these therapeutic regimens are concerned, tucatinib is a Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) with biochemical high specificity against HER-2 kinase domain [28]. The efficacy of tucatinib in combination with trastuzumab and capecitabine, was addressed in the phase II HER2CLIMB trial [29][30], leading to approval of this combination in 2020, for patients with advanced or metastatic HER-2+ mBC and have previously received anti-HER-2 based therapies. Notably, based on the results of this trial, on the arm of patients with brain metastasis, the 1-year PFS was 24.9%, compared to 0% in the placebo group [31][32], with subsequent increase in the reported quality of life [33], making this combination preferred for the brain metastatic disease (Figure 2). At this point, it is important to mention the recent developments in HER-2 low mBC. HER-2 low expression is generally defined as a IHC score of 1+ or as an IHC score of 2+ with negative results on in situ hybridization [32]. Based on the DESTINY-Breast04 clinical phase III trial, trastuzumab deruxtecan was compared with chemotherapy of physician’s choice. In this cohort, the PFS in the trastuzumab deruxtecan group was 9.9 months and 5.1 months in the physician’s choice group (HR = 0.50; p < 0.001), while the OS was 23.4 months and 16.8 months, respectively (HR = 0.64; p = 0.001) [33][34]. Based on these results, trastuzumab deruxtecan has been approved for the treatment of HER2-Low mBC. Furthermore, based on a recent clinical phase III trial, DESTINY-Breast03, trastuzumab deruxtecan achieved significantly longer progression free survival compared to trastuzumab emtansine (TDM-1) (HR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.86), in HER-2+ mBC patient who progressed following treatment with anti-HER2 antibodies and a taxane [35][36].

Another FDA-approved oral TKI, neratinib, irreversibly inhibits HER-1, HER-2 and HER-4, promoting cell death through ferroptosis induction [37]. NALA phase III clinical trial addresses the combination of neratinib with capecitabine with lapatinib plus capecitabine [38][39]. Overall, the neratinib plus capecitabine treatment significantly prolonged PFS and reduced the percentage of patients with brain metastatic disease that required CNS intervention [38][39]. Based on these results, neratinib plus capecitabine combination is approved for patients with advanced or metastatic HER-2+ mBC after two or more anti-HER-2 lines of therapy. Nevertheless, neratinib was characterized from grade 3 diarrhea, even though the patients received mandatory anti-diarrheal prophylaxis during the research. More importantly, the researchers need to mention that this clinical observation has been radically improved with the new dose escalation approaches, based on the CONTROL trial [40]. Last but not least, lapatinib is another FDA-approved oral TKI, reversibly inhibiting HER-1, HER-2 and EGFR. The results of a phase III clinical trial assessing the efficacy of lapatinib plus capecitabine compared to capecitabine alone, demonstrated that lapatinib treatment prolongs the progression interval, without increasing the observed side effects [41]. These results led to the FDA approval of lapatinib plus capecitabine for patients with HER-2+ mBC who had progressed upon treatment with anthracycline, taxanes, and trastuzumab (Figure 2).

3. Treatment of Triple Negative mBC

Compared to the two latter subtypes of breast cancer, Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) is characterized with significantly high risk of recurrence after treatment. Even though the majority of the patients presented with metastatic manifestations over the course of the disease in the past, in recent years the approval of new emerging therapies has significantly prolonged the survival and the pathological complete response (pCR) in this subgroup [42]. To begin with, the researchers need to mention several recent landmark clinical trials that have shaped the clinical management of TNBC mBC. Firstly, based on the ASCENT clinical trials [43] for the treatment of TNBC mBC, patients were treated with sacituzumab govitecan versus single-agent chemotherapy of the physician’s choice (eribulin, vinorelbine, capecitabine, or gemcitabine). Sacituzumab govitecan is an antibody–drug conjugate composed of SN-38 (topoisomerase I inhibitor) and an antibody targeting the human trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (Trop-2), coupled through a linker. Based on this research, the median progression-free survival in patients treated with sacituzumab govitecan was 5.6 months (95% CI, 4.3 to 6.3) and 1.7 months (95% CI, 1.5 to 2.6) compared with those treated with chemotherapy alone (HR = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.32 to 0.52; p < 0.001) [43].

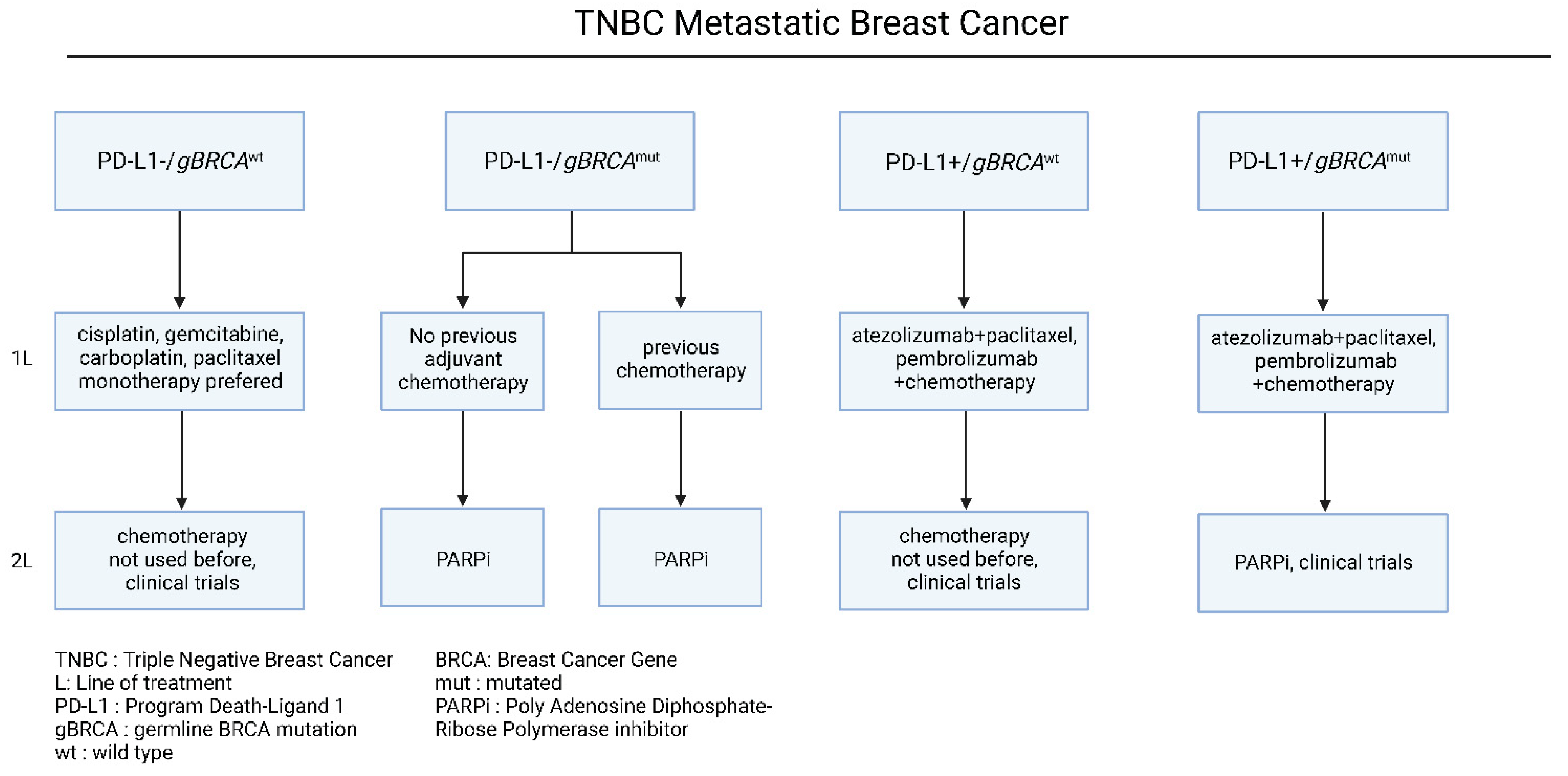

Nevertheless, TNBC is also characterized by extensive chemo-sensitivity with high rates of pathological complete response after chemotherapy among the other breast cancer subtypes [14]. Based on recent advancements in molecular target identification, Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and germline Breast Cancer gene (gBRCA) mutational status have been identified as main determinants of therapeutic approaches (Figure 3). To begin with, in patients with negative PD-L1 expression and wild type BRCA status, cytotoxic chemotherapy agents are considered the treatment of choice [44][45][46], especially in patients who have not received this chemotherapy class before [44][45][46]. Even though chemotherapy is associated with higher clinical response rates, and it is preferred in patients with extensive visceral disease, it has not been proved to prolong the overall and progression-free survival [12][13].

In patients harboring germline BRCA mutations, the therapeutic approach includes the usage of platins-based chemotherapy and/or PARP inhibitors. The BRCA genes (BRCA1, BRCA2) encode proteins that participate in the DNA double-stranded breaks and homologous recombination, with their mutations to induce significant impairment in the DNA repair system [47]. On the one hand, platin-based chemotherapy introduces multiple single-stranded breaks in DNA, leading to synthetic lethality and apoptosis in gBRCAmut tumors, due to their inability to repair DNA breaks [47]. On the other hand, Polyadenosine Diphosphate-Ribose Polymerase (PARP) complex maintains cellular homeostasis through a plethora of biological functions, that include the DNA repair system [48]. Similar to platins, PARP inhibitors interfere with the DNA damage response, leading to synthetic lethality in gBRCAmut patients [49][50]. The effectiveness of platinum-based chemotherapy in HR+/HER-2− and TNBC patients was proved in the TNT phase III clinical trial, in which carboplatin significantly enhanced the response rates (68% vs. 33%) and prolonged the PFS (6.8 vs. 4.4 months), compared to docetaxel [51]. In the case of PARP inhibitors, two large phase III clinical trials, namely the OLYMPIAD and EMBRACA studies, demonstrated significantly prolonged PFS in the PARP inhibitor group, compared to chemotherapy (7.0 vs. 4.2 months in OLYMPIAD and 8.6 vs. 5.6 months in EMBRACA) [52][53]. Notably, in both trials, PARP inhibition was associated with grade 3 hematological toxicities. These studies led to the FDA approval of talazoparib and olaparib for patients with gBRCAmut/HER-2− metastatic breast cancer in 2018.

On the other hand, due to its unique biological background, TNBC is considered highly immunogenic, a characteristic linked with its high tumor mutational burden (TMB), among the other breast cancer subtypes [54]. To this extent, given that high TMB is associated with the generation of neoantigens and immune cell infiltration in the tumor-microenvironment [55], the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the clinical outcomes of TNBC patients has been previously investigated. In the large stage III clinical trial Impassion 130, the combination of nab-paclitaxel with atezolizumab was compared to nab-paclitaxel alone in patients with metastatic TNBC. Based on the results of this trial, the atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel combination significantly prolonged the PFS compared to nab-paclitaxel alone (7.2 vs. 5.5 months, HR = 0.8, p = 0.002), without demonstrating any benefit in the OS (21.3 vs. 17.6 months, HR = 0.84, p = 0.08) [56]. Notably, specifically in the PD-L1+ patient subgroup, the investigated combination achieved prolonged PFS (7.5 vs. 5.0 months, HR = 0.62, p < 0.001) and OS (25.0 vs. 15.5 months, HR = 0.62, p < 0.001), compared to monotherapy, with parallel toxicity profiling [56][57]. It is important to mention that regardless of these results, the atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel combination approval for metastatic TNBC has been withdrawn by the FDA. More importantly, according to the KEYNOTE-355 clinical phase III, the addition of pembrolizumab to chemotherapy led to significantly longer PFS than chemotherapy alone, in patients with PD-L1+ (CPS > 10) mBC TNBC (HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55 to 0.95; p = 0.0185) [57][58]. Further clinical studies with a larger patient cohort are needed to address its effectiveness in PD-L1+ TNBC patients [58] (Figure 3). Given that TNBC has a higher frequency metastasizing in the brain, a summary of proposed therapeutic choices and indications for brain metastasis mBC are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Brain Metastasis Treatment.

| Indication | Therapy |

|---|---|

| Single, surgically accessible metastasis with favorable prognosis | Surgical resection [59][60][61][62][63][64] Whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) [65] |

| Single, surgically inaccessible metastasis with favorable prognosis | Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS) with WBRT [66][67][68][69] |

| Multiple < 3 cm brain metastases, with favorable prognosis | SRS alone [70] Adjunctive WBRT [71] |

| Poor prognosis/PS | WBRT vs. SRS [72][73] |

| Patients with progressive extracranial disease or no feasible local therapy option | Systemic therapy based on subtypes [74] |

References

- McAndrew, N.P.; Finn, R.S. Clinical review on the management of hormone receptor–positive metastatic breast cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, 319–327.

- Giuliano, M.; Schettini, F.; Rognoni, C.; Milani, M.; Jerusalem, G.; Bachelot, T.; De Laurentiis, M.; Thomas, G.; De Placido, P.; Arpino, G.; et al. Endocrine treatment versus chemotherapy in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1360–1369.

- Taylor, C.W.; Green, S.; Dalton, W.S.; Martino, S.; Rector, D.; Ingle, J.N.; Robert, N.J.; Budd, G.T.; Paradelo, J.C.; Natale, R.B.; et al. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of goserelin versus surgical ovariectomy in premenopausal patients with receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: An intergroup study. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 994–999.

- Carey, L.A.; Solovieff, N.; Andre, F.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Cameron, A.; Janni, W.; Sonke, G.; Yap, Y.; Yardley, D.; Zarate, J.; et al. Correlative analysis of overall survival by intrinsic subtype across the MONALEESA-2, -3, and -7 studies of ribociclib + endocrine therapy in patients with HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer. In Proceedings of the 2021 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), San Antonio, TX, USA, 7–10 December 2021.

- Finn, R.S.; Crown, J.P.; Lang, I.; Boer, K.; Bondarenko, I.M.; Kulyk, S.O.; Ettl, J.; Patel, R.; Pinter, T.; Schmidt, M.; et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): A randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 25–35.

- Mehta, R.S.; Barlow, W.E.; Albain, K.S.; Vandenberg, T.A.; Dakhil, S.R.; Tirumali, N.R.; Lew, D.L.; Hayes, D.F.; Gralow, J.R.; Linden, H.M.; et al. Overall Survival with Fulvestrant plus Anastrozole in Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1226–1234.

- Bergh, J.; Jönsson, P.E.; Lidbrink, E.K.; Trudeau, M.; Eiermann, W.; Brattström, D.; Lindemann, J.P.; Wiklund, F.; Henriksson, R. FACT: An open-label randomized phase III study of fulvestrant and anastrozole in combination compared with anastrozole alone as first-line therapy for patients with receptor-positive postmenopausal breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1919–1925.

- Mauri, D.; Pavlidis, N.; Polyzos, N.P.; Ioannidis, J.P. Survival with aromatase inhibitors and inactivators versus standard hormonal therapy in advanced breast cancer: Meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 1285–1291.

- Ye, Z.; Wang, C.; Wan, S.; Mu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Abu-Khalaf, M.M.; Fellin, F.M.; Silver, D.P.; Neupane, M.; Jaslow, R.J.; et al. Association of clinical outcomes in metastatic breast cancer patients with circulating tumour cell and circulating cell-free DNA. Eur. J Cancer 2019, 106, 133–143.

- Kornblum, N.; Zhao, F.; Manola, J.; Klein, P.; Ramaswamy, B.; Brufsky, A.; Stella, P.J.; Burnette, B.; Telli, M.; Makower, D.F.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Fulvestrant Plus Everolimus or Placebo in Postmenopausal Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer Resistant to Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy: Results of PrE0102. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1556–1563.

- André, F.; Ciruelos, E.; Rubovszky, G.; Campone, M.; Loibl, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Iwata, H.; Conte, P.; Mayer, I.A.; Kaufman, B.; et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1929–1940.

- Piccart-Gebhart, M.J.; Burzykowski, T.; Buyse, M.; Sledge, G.; Carmichael, J.; Lück, H.-J.; Mackey, J.R.; Nabholtz, J.-M.; Paridaens, R.; Biganzoli, L.; et al. Taxanes alone or in combination with anthracyclines as first-line therapy of patients with metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 1980–1986.

- Chan, S.; Romieu, G.; Huober, J.; Delozier, T.; Tubiana-Hulin, M.; Schneeweiss, A.; Lluch, A.; Llombart, A.; du Bois, A.; Kreienberg, R.; et al. Phase III study of gemcitabine plus docetaxel compared with capecitabine plus docetaxel for anthracycline-pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 1753–1760.

- Thomas, E.S. Ixabepilone plus capecitabine for metastatic breast cancer progressing after anthracycline and taxane treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2223.

- Clark, G.M.; Sledge, G.W., Jr.; Osborne, C.K.; McGuire, W.L. Survival from first recurrence: Relative importance of prognostic factors in 1,015 breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 1987, 5, 55–61.

- Martínez-Sáez, O.; Prat, A. Current and future management of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, 594–604.

- Swain, S.M.; Baselga, J.; Kim, S.B.; Ro, J.; Semiglazov, V.; Campone, M.; Ciruelos, E.; Ferrero, J.M.; Schneeweiss, A.; Heeson, S.; et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 724–734.

- Gobbini, E.; Ezzalfani, M.; Dieras, V.; Bachelot, T.; Brain, E.; Debled, M.; Jacot, W.; Mouret-Reynier, M.A.; Goncalves, A.; Dalenc, F.; et al. Time trends of overall survival among metastatic breast cancer patients in the real-life ESME cohort. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 96, 17–24.

- Baselga, J.; Swain, S.M. CLEOPATRA: A phase III evaluation of pertuzumab and trastuzumab for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2010, 10, 489–491.

- Scheuer, W.; Friess, T.; Burtscher, H.; Bossenmaier, B.; Endl, J.; Hasmann, M. Strongly enhanced antitumor activity of trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination treatment on HER2-positive human xenograft tumor models. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 9330–9336.

- Hao, Y.; Yu, X.; Bai, Y.; McBride, H.J.; Huang, X. Cryo-EM Structure of HER2-trastuzumab-pertuzumab complex. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216095.

- Bachelot, T.; Ciruelos, E.; Schneeweiss, A.; Puglisi, F.; Peretz-Yablonski, T.; Bondarenko, I.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Wardley, A.; Merot, J.L.; Du Toit, Y.; et al. Preliminary safety and efficacy of first-line pertuzumab combined with trastuzumab and taxane therapy for HER2-positive locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer (PERUSE). Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 766–773.

- Perez, E.A.; L’opez-Vega, J.M.; Petit, T.; Zamagni, C.; Easton, V.; Kamber, J.; Restuccia, E.; Andersson, M. Safety and efficacy of vinorelbine in combination with pertuzumab and trastuzumab for first-line treatment of patients with HER2-positive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: VELVET cohort 1 final results. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 126.

- Verma, S.; Miles, D.; Gianni, L.; Krop, I.E.; Welslau, M.; Baselga, J.; Pegram, M.; Oh, D.Y.; Diéras, V.; Guardino, E.; et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1783–1791.

- Diéras, V.; Miles, D.; Verma, S.; Pegram, M.; Welslau, M.; Baselga, J.; Krop, I.E.; Blackwell, K.; Hoersch, S.; Xu, J.; et al. Trastuzumab emtansine versus capecitabine plus lapatinib in patients with previously treated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (EMILIA): A descriptive analysis of final overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 732–742.

- Krop, I.E.; Kim, S.B.; González-Martín, A.; LoRusso, P.M.; Ferrero, J.M.; Smitt, M.; Yu, R.; Leung, A.C.; Wildiers, H. Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physician’s choice for pretreated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (TH3RESA): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 689–699.

- Krop, I.E.; Kim, S.B.; Martin, A.G.; LoRusso, P.M.; Ferrero, J.M.; Badovinac-Crnjevic, T.; Hoersch, S.; Smitt, M.; Wildiers, H. Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with previously treated HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (TH3RESA): Final overall survival results from a randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 743–754.

- Pheneger, T.; Bouhana, K.; Anderson, D.; Garrus, J.; Ahrendt, K.; Allen, S. In vitro and in vivo activity of ARRY-380: A potent, small molecule inhibitor of ErbB2. In Proceedings of the American Association for Cancer Research, Denver, CO, USA, 18–22 April 2009.

- Murthy, R.K.; Loi, S.; Okines, A.; Paplomata, E.; Hamilton, E.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Lin, N.U.; Borges, V.; Abramson, V.; Anders, C.; et al. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 597–609.

- Lin, N.U.; Borges, V.; Anders, C.; Murthy, R.K.; Paplomata, E.; Hamilton, E.; Hurvitz, S.; Loi, S.; Okines, A.; Abramson, V.; et al. Intracranial efficacy and survival with tucatinib plus trastuzumab and capecitabine for previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer with brain metastases in the HER2CLIMB trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2610.

- Wardley, A.; Mueller, V.; Paplomata, E.; Crouzet, L.; Iqbal, N.; Aithal, S.; Block, M.; Cold, S.; Hahn, O.; Poosarla, T.; et al. Abstract PD13-04: Impact of tucatinib on health-related quality of life in patients with HER2 metastatic breast cancer with stable and active brain metastases. In Proceedings of the 2020 San Antonio Breast Cancer Virtual Symposium, San Antonio, TX, USA, 8–11 December 2020.

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 9–20.

- Cortés, J.; Kim, S.B.; Chung, W.P.; Im, S.A.; Park, Y.H.; Hegg, R.; Kim, M.H.; Tseng, L.M.; Petry, V.; Chung, C.F.; et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1143–1154.

- Balduzzi, S.; Mantarro, S.; Guarneri, V.; Tagliabue, L.; Pistotti, V.; Moja, L.; D’Amico, R. Trastuzumab-containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD006242.

- Baselga, J.; Cortés, J.; Kim, S.B.; Im, S.-A.; Hegg, R.; Im, Y.-H.; Roman, L.; Pedrini, J.L.; Pienkowski, T.; Knott, A.; et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 109–119.

- Modi, S.; Saura, C.; Yamashita, T.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, S.-B.; Tamura, K.; Andre, F.; Iwata, H.; Ito, Y.; Tsurutani, J.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 610–621.

- Nagpal, A.; Redvers, R.P.; Ling, X.; Ayton, S.; Fuentes, M.; Tavancheh, E.; Diala, I.; Lalani, A.; Loi, S.; David, S.; et al. Neoadjuvant neratinib promotes ferroptosis and inhibits brain metastasis in a novel syngeneic model of spontaneous HER2+ve breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 94.

- Saura, C.; Oliveira, M.; Feng, Y.H.; Dai, M.S.; Chen, S.W.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Kim, S.B.; Moy, B.; Delaloge, S.; Gradishar, W.; et al. Neratinib plus capecitabine versus lapatinib plus capecitabine in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer previously treated with ≥2 HER2-directed regimens: Phase III NALA trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3138.

- Isakoff, S.J.; Baselga, J. Trastuzumab-DM1: Building a chemotherapy-free road in the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 351–354.

- Barcenas, C.H.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Di Palma, J.A.; Bose, R.; Chien, A.J.; Iannotti, N.; Marx, G.; Brufsky, A.; Litvak, A.; Ibrahim, E.; et al. Improved tolerability of neratinib in patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer: The CONTROL trial. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1223–1230.

- Geyer, C.E.; Forster, J.; Lindquist, D.; Chan, S.; Romieu, C.G.; Pienkowski, T.; Jagiello-Gruszfeld, A.; Crown, J.; Chan, A.; Kaufman, B.; et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2733–2743.

- Caparica, R.; Lambertini, M.; de Azambuja, E. How I treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. ESMO Open 2019, 4, e000504.

- Bardia, A.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Loirat, D.; Punie, K.; Oliveira, M.; Brufsky, A.; Sardesai, S.D.; Kalinsky, K.; Zelnak, A.B.; et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1529–1541.

- Won, K.A.; Spruck, C. Triple negative breast cancer therapy: Current and future perspectives. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 1245–1261.

- Adel, N.G. Current treatment landscape and emerging therapies for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Am. J. Manag. Care 2021, 27 (Suppl. 5), S87–S96.

- Zeichner, S.B.; Terawaki, H.; Gogineni, K. A review of systemic treatment in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2016, 10, BCBCR-S32783.

- Kieffer, S.R.; Lowndes, N.F. Immediate-Early, Early, and Late Responses to DNA Double Stranded Breaks. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 793884.

- Richard, I.A.; Burgess, J.T.; O’Byrne, K.J.; Bolderson, E. Beyond PARP1: The Potential of Other Members of the Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Family in DNA Repair and Cancer Therapeutics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 801200.

- Dhillon, K.K.; Bajrami, I.; Taniguchi, T.; Lord, C.J. Synthetic lethality: The road to novel therapies for breast cancer. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2016, 23, T39–T55.

- Ashworth, A.; Lord, C.J. Synthetic lethal therapies for cancer: What’s next after PARP inhibitors? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 564–576.

- Tutt, A.; Tovey, H.; Cheang, M.C.U.; Kernaghan, S.; Kilburn, L.; Gazinska, P.; Owen, J.; Abraham, J.; Barrett, S.; Barrett-Lee, P.; et al. Carboplatin in BRCA1/2-mutated and triple-negative breast cancer BRCAness subgroups: The TNT Trial. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 628–637.

- Litton, J.K.; Rugo, H.S.; Ettl, J.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Gonçalves, A.; Lee, K.-H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Yerushalmi, R.; Mina, L.A.; Martin, M.; et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 753–763.

- Robson, M.; Im, S.A.; Senkus, E.; Xu, B.; Domchek, S.M.; Masuda, N.; Delaloge, S.; Li, W.; Tung, N.; Armstrong, A.; et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 523–533.

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X. A comprehensive immunologic portrait of triple-negative breast cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 311–329.

- Denkert, C.; von Minckwitz, G.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Lederer, B.; Heppner, B.I.; Weber, K.E.; Budczies, J.; Huober, J.; Klauschen, F.; Furlanetto, J.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: A pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 40–50.

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.A.; Shaw Wright, G.; et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2108–2121.

- Kwapisz, D. Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 607–617.

- Cortes, J.; Rugo, H.S.; Cescon, D.W.; Im, S.A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Perez-Garcia, J.; Iwata, H.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 217–226.

- Rostami, R.; Mittal, S.; Rostami, P.; Tavassoli, F.; Jabbari, B. Brain metastasis in breast cancer: A comprehensive literature review. J. Neurooncol. 2016, 127, 407–414.

- Lockman, P.R.; Mittapalli, R.K.; Taskar, K.S.; Rudraraju, V.; Gril, B.; Bohn, K.A.; Adkins, C.E.; Roberts, A.; Thorsheim, H.R.; Gaasch, J.A.; et al. Heterogeneous blood–tumor barrier permeability determines drug efficacy in experimental brain metastases of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5664–5678.

- Mills, M.N.; Figura, N.B.; Arrington, J.A.; Yu, H.H.M.; Etame, A.B.; Vogelbaum, M.A.; Soliman, H.; Czerniecki, B.J.; Forsyth, P.A.; Han, H.S.; et al. Management of brain metastases in breast cancer: A review of current practices and emerging treatments. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 180, 279–300.

- Soffietti, R.; Abacioglu, U.; Baumert, B.; Combs, S.E.; Kinhult, S.; Kros, J.M.; Marosi, C.; Metellus, P.; Radbruch, A.; Villa Freixa, S.S.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of brain metastases from solid tumors: Guidelines from the European Association of Neuro-Oncology (EANO). Neuro-Oncology 2017, 19, 162–174.

- Patel, K.R.; Burri, S.H.; Asher, A.L.; Crocker, I.R.; Fraser, R.W.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Kandula, S.; Zhong, J.; Press, R.H.; et al. Comparing preoperative with postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery for resectable brain metastases: A multi-institutional analysis. Neurosurgery 2016, 79, 279–285.

- Brown, P.D.; Pugh, S.; Laack, N.N.; Wefel, J.S.; Khuntia, D.; Meyers, C.; Choucair, A.; Fox, S.; Suh, J.H.; Roberge, D.; et al. Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro-Oncology 2013, 15, 1429–1437.

- Gondi, V.; Deshmukh, S.; Brown, P.D.; Wefel, J.S.; Tome, W.A.; Bruner, D.W.; Bovi, J.A.; Robinson, C.G.; Khuntia, D.; Grosshans, D.R.; et al. Preservation of neurocognitive function (NCF) with conformal avoidance of the hippocampus during whole-brain radiotherapy (HA-WBRT) for brain metastases: Preliminary results of phase III trial NRG oncology CC001. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 102, 1607.

- Brown, P.D.; Ballman, K.V.; Cerhan, J.H.; Anderson, S.K.; Carrero, X.W.; Whitton, A.C.; Greenspoon, J.; Parney, I.F.; Laack, N.N.; Ashman, J.B.; et al. Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery compared with whole brain radiotherapy for resected metastatic brain disease (NCCTG N107C/CEC·3): A multicentre, randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1049–1060.

- Kayama, T.; Sato, S.; Sakurada, K.; Mizusawa, J.; Nishikawa, R.; Narita, Y.; Sumi, M.; Miyakita, Y.; Kumabe, T.; Sonoda, Y.; et al. Effects of surgery with salvage stereotactic radiosurgery versus surgery with whole-brain radiation therapy in patients with one to four brain metastases (JCOG0504): A phase III, noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3282–3289.

- Yamamoto, M.; Serizawa, T.; Shuto, T.; Akabane, A.; Higuchi, Y.; Kawagishi, J.; Yamanaka, K.; Sato, Y.; Jokura, H.; Yomo, S.; et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901): A multi-institutional prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 387–395.

- Sahgal, A.; Aoyama, H.; Kocher, M.; Neupane, B.; Collette, S.; Tago, M.; Shaw, P.; Beyene, J.; Chang, E.L. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 91, 710–717.

- Sawaya, R.; Hammoud, M.; Schoppa, D.; Hess, K.R.; Wu, S.Z.; Shi, W.-M.; WiIdrick, D.M. Neurosurgical outcomes in a modern series of 400 craniotomies for treatment of parenchymal tumors. Neurosurgery 1998, 42, 1044–1056.

- Patchell, R.A.; Tibbs, P.A.; Regine, W.F.; Dempsey, R.J.; Mohiuddin, M.; Kryscio, R.J.; Markesbery, W.R.; Foon, K.A.; Young, B. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: A randomized trial. JAMA 1998, 280, 1485–1489.

- Fuentes, R.; Osorio, D.; Expósito Hernandez, J.; Simancas-Racines, D.; Martinez-Zapata, M.J.; Bonfill Cosp, X. Surgery versus stereotactic radiotherapy for people with single or solitary brain metastasis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD012086.

- Mekhail, T.; Sombeck, M.; Sollaccio, R. Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: Results of the EORTC 22952-26001 study. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 13, 255–258.

- Chernov, M.F.; Nakaya, K.; Izawa, M.; Hayashi, M.; Usuba, Y.; Kato, K.; Muragaki, Y.; Iseki, H.; Hori, T.; Takakura, K. Outcome after radiosurgery for brain metastases in patients with low Karnofsky performance scale (KPS) scores. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007, 67, 1492–1498.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

879

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Oct 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No