| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dean Liu | -- | 851 | 2022-10-14 01:37:10 |

Video Upload Options

The Tanpopo mission is an orbital astrobiology experiment investigating the potential interplanetary transfer of life, organic compounds, and possible terrestrial particles in the low Earth orbit. The purpose is to assess the panspermia hypothesis and the possibility of natural interplanetary transport of microbial life as well as prebiotic organic compounds. The collection and exposure phase took place from May 2015 through February 2018 utilizing the Exposed Facility located on the exterior of Kibo, the Japanese Experimental Module of the International Space Station. The mission, designed and performed by Japan, used ultra-low density silica gel (aerogel) to collect cosmic dust by, which is being analyzed for amino acid-related compounds and microorganisms following their return to Earth. The last samples were retrieved in February 2018 and analyses are ongoing. The principal investigator is Akihiko Yamagishi, who heads a team of researchers from 26 universities and institutions in Japan, including JAXA.

1. Mission

The capture and exposure experiments in the Tanpopo mission were designed to confirm the hypothesis that extraterrestrial organic compounds played important roles in the generation of the first terrestrial life, as well as examination of the hypothesis of panspermia. If the Tanpopo mission can detect microbes at the higher altitude of low Earth orbit (400 km), it will support the possible interplanetary migration of terrestrial life.[1][2] The mission was named after the plant dandelion (Tanpopo) because the plant's seeds evoke the image of seeds of lifeforms spreading out through space.

The Tanpopo mission exposures took place at the Exposed Facility located on the exterior of the Kibo module of the ISS from May 2015 through February 2018.[3] It collected cosmic dust and exposed dehydrated microorganisms outside the International Space Station while orbiting 400 km (250 mi) above the Earth. These experiments will test some aspects of panspermia, a hypothesis for an exogenesis origin of life distributed by meteoroids, asteroids, comets and cosmic dust.[4] This mission will also test if terrestrial microbes (e.g., aerosols embedding microbial colonies) may be present, even temporarily and in freeze-dried form in the low Earth orbit altitudes.[4]

Three key microorganisms include Deinococcus species: D. radiodurans, D. aerius and D. aetherius.[5] Containers holding yeast and other microbes were also placed outside the Kibo module to examine whether microbes can survive being exposed to the harsh cold environment of outer space. Also, by evaluating retrieved samples of exposed terrestrial microbes and astronomical organic analogs on the exposure panels, they can investigate their survival and any alterations in the duration of interplanetary transport.

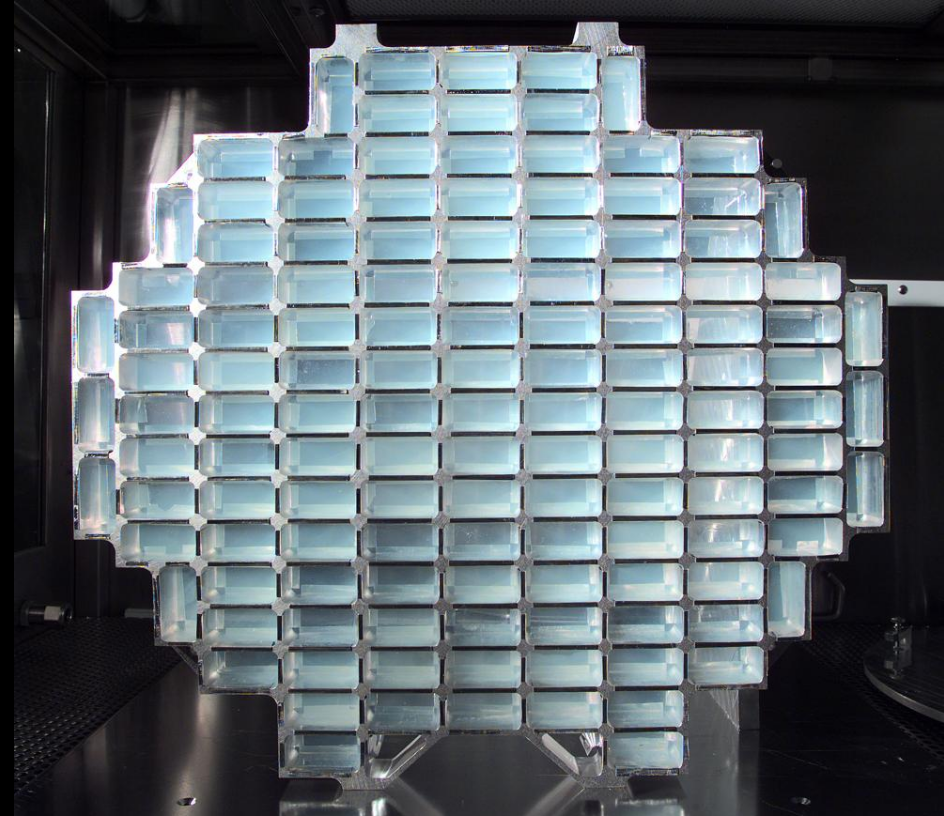

Researchers also aim to capture organic compounds and prebiotic organic compounds — such as aminoacids — drifting in space.[6] The mission collected cosmic dust and other particles for three years by using a two-layer aerogel ultra-low density silica gel collector with a density of 0.01 g/cc (0.0058 oz/cu in) for the upper layer and ~0.03 g/cc (0.017 oz/cu in) for the base layer.[4] Some of the aerogel collectors were replaced every one to two years through February 2018.[3][6]

The official ISS experiment code name is "Astrobiology Japan" representing "Astrobiology exposure and micrometeoroid capture experiments".[7]

2. Objectives

The objectives of Tanpopo lie in following 6 topics:[8]

- Sources of organic compounds to the surface of Earth[9]

- Organic compounds on micrometeorites are being exposed to the space environment before return to Earth for analyses

- Possibility for terrestrial microbe detection at the ISS orbital altitude due to the processes of volcanic eruptions, thunderstorms, meteorite impacts, and electromagnetic fields around the Earth

- Survival of some species of microbes in the space environment

- Capture of artificial micro-particles (space debris) by aerogel

- Two aerogel densities to capture particles moving at high velocity

3. Analyses

The aerogels were placed and retrieved by using the robotic arm outside Kibo. The first year samples were returned to Earth in mid-2016,[9] panels from the second year were brought back in late 2017, and the last set ended exposure in February 2018.[3] The last aerogels were placed inside the 'landing & return capsule' in early 2018 and ejected toward Earth for retrieval.[4] After retrieving the aerogels, scientists are investigating the captured microparticles and tracks formed, followed by microbiological, organochemical and mineralogical analyses. Particles potentially containing microbes will be used for PCR amplification of rRNA genes followed by DNA sequencing.[10]

Early mission results from the first sample show evidence that some clumps of microorganism can survive for at least one year in space.[11] This may support the idea that clumps greater than 0.5 millimeters of microorganisms could be one way for life to spread from planet to planet.[11] It was also noted that glycine's decomposition was less than expected, while hydantoin's recovery was much lower than glycine.[12]

In August 2020, scientists reported that bacteria from Earth, particularly Deinococcus radiodurans bacteria, which is highly resistant to environmental hazards, were found to survive for three years in outer space, based on studies conducted on the International Space Station. These findings support the notion of panspermia, the hypothesis that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed in various ways, including space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, planetoids or contaminated spacecraft.[13][14]

References

- Microbe space exposure experiment at International Space Station (ISS) proposed in "Tanpopo" mission. Research Gate, July 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241270775_Microbe_space_exposure_experiment_at_International_Space_Station_(ISS)_proposed_in_Tanpopo_mission

- In-orbit operation and initial sample analysis and curation results for the first year collection samples of the Tanpopo project. H. Yano, S. Sasaki, J. Imani, D. Horikawa, A. Yamagishi8, et al. Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2017/pdf/3040.pdf

- Tanpopo - Expedition Duration. Published by NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/experiments/2201.html

- "Tanpopo Experiment for Astrobiology Exposure and Micrometeoroid Capture Onboard the ISS-JEM Exposed Facility." (PDF) H. Yano, A. Yamagishi, H. Hashimoto1, S. Yokobori, K. Kobayashi, H. Yabuta, H. Mita, M. Tabata H., Kawai, M. Higashide, K. Okudaira, S. Sasaki, E. Imai, Y. Kawaguchi, Y. Uchibori11, S. Kodaira and the Tanpopo Project Team. 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014). http://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2014/pdf/2934.pdf

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Kawashiri, N.; Shiraishi, K.; Takasu, M.; Narumi, I.; Satoh, K.; Hashimoto, H. et al. (2013). "The possible interplanetary transfer of microbes: assessing the viability of Deinococcus spp. under the ISS Environmental conditions for performing exposure experiments of microbes in the Tanpopo mission". Orig Life Evol Biosph 43 (4–5): 411–28. doi:10.1007/s11084-013-9346-1. PMID 24132659. Bibcode: 2013OLEB...43..411K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11084-013-9346-1

- Tanpopo mission to search space for origins of life. The Japan News, April 16, 2015. http://the-japan-news.com/news/article/0002066967

- Space as a Tool for Astrobiology: Review and Recommendations for Experimentations in Earth Orbit and Beyond. Space Science Reviews. Hervé Cottin, et al. July 2017, Volume 209, Issue 1–4, pp 83–181 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11214-017-0365-5

- Astrobiology Exposure and Micrometeoroid Capture Experiments (Tanpopo). 18 October 2017. Hideyuki Watanabe. JAXA. Published by NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/experiments/2201.html

- Kawaguchi, Yuko (13 May 2016). "Investigation of the Interplanetary Transfer of Microbes in the Tanpopo Mission at the Exposed Facility of the International Space Station". Astrobiology 16 (5): 363–376. doi:10.1089/ast.2015.1415. PMID 27176813. Bibcode: 2016AsBio..16..363K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1089%2Fast.2015.1415

- Tanpopo mission: Astrobiology exposure and capture experiments of microbes and micrometeoroid. (PDF) Yuko Kawaguchi. 2014. http://www.dlr.de/me/en/Portaldata/25/Resources/dokumente/institut_me/institutsseminar/abstracts_2014/abstract_kawaguchi_y_09102014.pdf

- Early Tanpopo mission results show microbes can survive in space. American Geophysical Union - Geospace. Larry O'Hanlon. 19 May 2017. http://blogs.agu.org/geospace/2017/05/19/early-tanpopo-mission-results-show-microbes-can-survive-space/

- Current State of Organics Exposure Experiments In the Tanpopo Mission (PDF). K. Kobayashi, H. Mita, H. Y. Kebukawa, K. Nakagawa, E. Imai, H. Yano, H. Hashimoto, S. Yokobori, A. Yamagishi. JAXA. January 2017. https://repository.exst.jaxa.jp/dspace/bitstream/a-is/609841/1/SA6000060153.pdf

- Strickland, Ashley (26 August 2020). "Bacteria from Earth can survive in space and could endure the trip to Mars, according to new study". CNN News. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/26/world/earth-mars-bacteria-space-scn/index.html.

- Kawaguchi, Yuko (26 August 2020). "DNA Damage and Survival Time Course of Deinococcal Cell Pellets During 3 Years of Exposure to Outer Space". Frontiers in Microbiology 11: 2050. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.02050. PMID 32983036. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7479814