| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 6394 | 2022-10-12 01:35:06 |

Video Upload Options

The class of Sudoku puzzles consists of a partially completed row-column grid of cells partitioned into N regions each of size N cells, to be filled in ("solved") using a prescribed set of N distinct symbols (typically the numbers {1, ..., N}), so that each row, column and region contains exactly one of each element of the set. The properties of Sudoku puzzles and their solutions can be investigated using mathematics and algorithms.

1. Overview

The analysis of Sudoku falls into two main areas: analyzing the properties of (1) completed grids and (2) puzzles. Also studied are computer algorithms to solve Sudokus, and to develop (or search for) new Sudokus. Analysis has largely focused on enumerating solutions, with results first appearing in 2004.[1] There are many Sudoku variants, partially characterized by size (N), and the shape of their regions. Unless noted, discussion in this article assumes classic Sudoku, i.e. N=9 (a 9×9 grid and 3×3 regions). A rectangular Sudoku uses rectangular regions of row-column dimension R×C. Other variants include those with irregularly-shaped regions or with additional constraints (hypercube) or different constraint types (Samunamupure).

A puzzle is a partially completed grid, and the initial values are givens or clues. Regions are also called blocks or boxes. Horizontally adjacent rows are a band, and vertically adjacent columns are a stack. A proper puzzle has a unique solution. See Glossary of Sudoku for other terminology.[2] Solving Sudokus from the viewpoint of a player has been explored in Denis Berthier's book "The Hidden Logic of Sudoku" (2007)[3] which considers strategies such as "hidden xy-chains".

1.1. Mathematical Context

The general problem of solving Sudoku puzzles on n2×n2 grids of n×n blocks is known to be NP-complete.[4] For n=3 (classical Sudoku), however, this result is of little relevance: algorithms such as Dancing Links can solve puzzles in fractions of a second.

A puzzle can be expressed as a graph coloring problem.[5] The aim is to construct a 9-coloring of a particular graph, given a partial 9-coloring. The graph has 81 vertices, one vertex for each cell. The vertices are labeled with ordered pairs (x, y), where x and y are integers between 1 and 9. In this case, two distinct vertices labeled by (x, y) and (x′, y′) are joined by an edge if and only if:

- x = x′ (same column) or,

- y = y′ (same row) or,

- ⌈ x/3 ⌉ = ⌈ x′/3 ⌉ and ⌈ y/3 ⌉ = ⌈ y′/3 ⌉ (same 3×3 cell)

The puzzle is then completed by assigning an integer between 1 and 9 to each vertex, in such a way that vertices that are joined by an edge do not have the same integer assigned to them.

A Sudoku solution grid is also a Latin square.[5] There are significantly fewer Sudoku grids than Latin squares because Sudoku imposes the additional regional constraint. Nonetheless, the number of Sudoku grids was calculated by Bertram Felgenhauer and Frazer Jarvis in 2005 to be 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960[6](sequence A107739 in the OEIS). The number computed by Felgenhauer and Jarvis confirmed a result first identified by QSCGZ in September 2003.[6] This number is equal to 9! × 722 × 27 × 27,704,267,971, the last factor of which is prime. The result was derived through logic and brute force computation. Russell and Jarvis also showed that when symmetries were taken into account, there were 5,472,730,538 solutions[7] (sequence A109741 in the OEIS). The number of grids for 16×16 Sudoku is not known.

The number of minimal Sudokus (Sudokus in which no clue can be deleted without losing uniqueness of the solution) is not precisely known. However, statistical techniques combined with a generator ('Unbiased Statistics of a CSP – A Controlled-Bias Generator'),[8] show that there are approximately (with 0.065% relative error):

- 3.10 × 1037 minimal puzzles,

- 2.55 × 1025 non-essentially-equivalent minimal puzzles.

Other authors used faster methods and calculated additional precise distribution statistics.[9]

1.2. Sudokus from Group Tables

As in the case of Latin squares the (addition- or) multiplication tables (Cayley tables) of finite groups can be used to construct Sudokus and related tables of numbers. Namely, one has to take subgroups and quotient groups into account:

Take for example [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{n}\oplus\mathbb{Z}_{n} }[/math] the group of pairs, adding each component separately modulo some [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. By omitting one of the components, we suddenly find ourselves in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{n} }[/math] (and this mapping is obviously compatible with the respective additions, i.e. it is a group homomorphism). One also says that the latter is a quotient group of the former, because some once different elements become equal in the new group. However, it is also a subgroup, because we can simply fill the missing component with [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] to get back to [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{n}\oplus\mathbb{Z}_{n} }[/math].

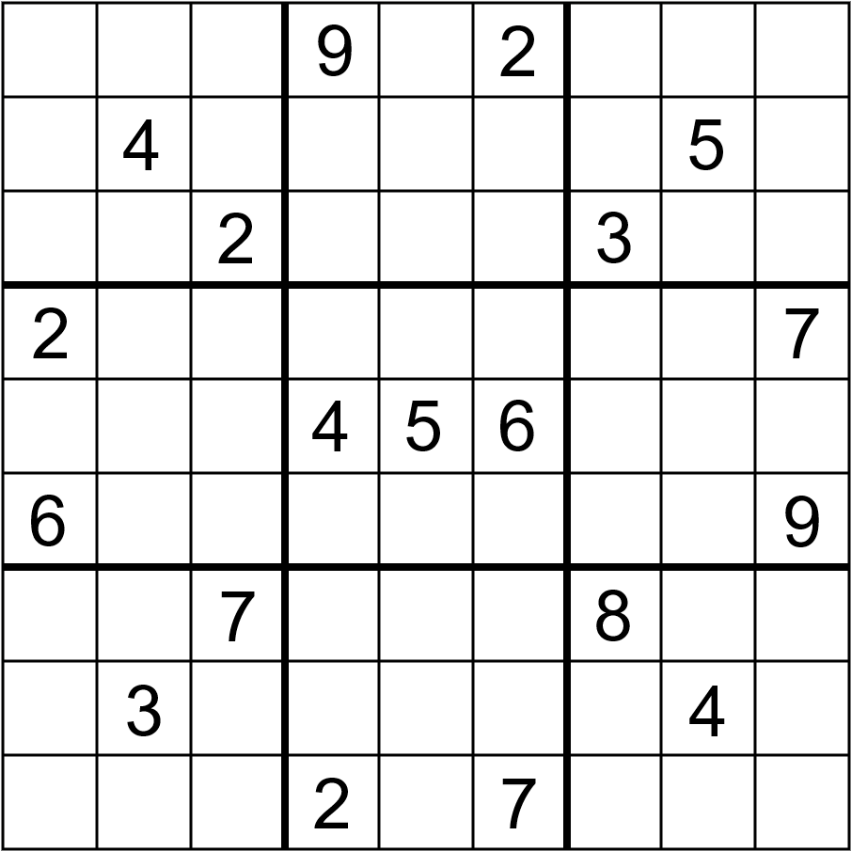

Under this view, we write down the example, Grid 1, for [math]\displaystyle{ n=3 }[/math].

Each Sudoku region looks the same on the second component (namely like the subgroup [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{3} }[/math]), because these are added regardless of the first one. On the other hand, the first components are equal in each block, and if we imagine each block as one cell, these first components show the same pattern (namely the quotient group [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{3} }[/math]). As outlined in the article of Latin squares, this is a Latin square of order [math]\displaystyle{ 9 }[/math].

Now, to yield a Sudoku, let us permute the rows (or equivalently the columns) in such a way, that each block is redistributed exactly once into each block – for example order them [math]\displaystyle{ 1,4,7,2,5,8,3,6,9 }[/math]. This of course preserves the Latin square property. Furthermore, in each block the lines have distinct first component by construction and each line in a block has distinct entries via the second component, because the blocks' second components originally formed a Latin square of order [math]\displaystyle{ 3 }[/math] (from the subgroup [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{3} }[/math]). Thus we arrive at a Sudoku (rename the pairs to numbers 1...9 if you wish). With the example and the row permutation above, we arrive at Grid 2.

For this method to work, one generally does not need a product of two equally-sized groups. A so-called short exact sequence of finite groups of appropriate size already does the job. Try for example the group [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{4} }[/math] with quotient- and subgroup [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}_{2} }[/math]. It seems clear (already from enumeration arguments), that not all Sudokus can be generated this way.

2. Enumerating Sudoku Solutions

The answer to the question 'How many Sudoku grids are there?' depends on the definition of when similar solutions are considered different.

2.1. Enumerating All Possible Sudoku Solutions

For the enumeration of all possible solutions, two solutions are considered distinct if any of their corresponding (81) cell values differ. Symmetry relations between similar solutions are ignored., e.g. the rotations of a solution are considered distinct. Symmetries play a significant role in the enumeration strategy, but not in the count of all possible solutions.

The first known solution to complete enumeration was posted by QSCGZ [Guenter Stertenbrink] to the rec.puzzles newsgroup in 2003,[6][10][11] obtaining 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 (6.67×1021) distinct solutions.

In a 2005 study, Felgenhauer and Jarvis[12] analyzed the permutations of the top band used in valid solutions. Once the Band1 symmetries and equivalence classes for the partial grid solutions were identified, the completions of the lower two bands were constructed and counted for each equivalence class. Summing completions over the equivalence classes, weighted by class size, gives the total number of solutions as 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960, confirming the value obtained by QSCGZ. The value was subsequently confirmed numerous times independently. A second enumeration technique based on band generation was later developed that is significantly less computationally intensive.

2.2. Enumerating Essentially Different Sudoku Solutions

Two valid grids are essentially the same if one can be derived from the other. The following operations are Sudoku preserving symmetries and always translate a valid grid into another valid grid:

- Relabeling symbols (9!)

- Band permutations (3!)

- Row permutations within a band (3!3)

- Stack permutations (3!)

- Column permutations within a stack (3!3)

- Reflection, transposition and rotation (2). (Given any transposition or quarter-turn rotation in conjunction with the above permutations, any combination of reflections, transpositions and rotations can be produced, so these operations only contribute a factor of 2.)

These operations define a symmetry relation between equivalent grids. Excluding relabeling, and with respect to the 81 grid cell values, the operations form a subgroup of the symmetric group S81, of order 3!8×2 = 3,359,232. Applying the above operations on majority of the grids results in 3!8×2×9! essentially equivalent grids. Exceptions are Automorphic Sudokus which due to additional non-trivial symmetry generate fewer grids.

The number of distinct solutions can also be identified with Burnside's Lemma. For a solution, the set of equivalent solutions which can be reached using these operations (excluding relabeling), form an orbit of the symmetric group. The number of essentially different solutions is then the number of orbits, which can be computed using Burnside's lemma. The Burnside fixed points are solutions that differ only by relabeling. Using this technique, Jarvis/Russell[7] computed the number of essentially different (symmetrically distinct) solutions as 5,472,730,538.

3. Enumeration Results

Enumeration results for many Sudoku variants have been calculated: these are summarised below.

3.1. Sudoku with Rectangular Regions

In the table, "Dimensions" are those of the regions (e.g. 3x3 in normal Sudoku). The "Rel Err" column indicates how a simple approximation, using the generalised method of Kevin Kilfoil,[13] compares to the true grid count: it is an underestimate in all cases evaluated so far.

| Dimensions | Nr Grids | Attribution | Verified? | Rel Err |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1x? | see Latin squares | n/a | ||

| 2×2 | 288 | various[14][15] | Yes | -11.1% |

| 2×3 | 28200960 = c. 2.8×107 | Pettersen[16] | Yes | -5.88% |

| 2×4 | 29136487207403520 = c. 2.9×1016 | Russell[17] | Yes | -1.91% |

| 2×5 | 1903816047972624930994913280000 = c. 1.9×1030 | Pettersen[18] | Yes | -0.375% |

| 2×6 | 38296278920738107863746324732012492486187417600000 = c. 3.8×1049 | Pettersen[19] | No | -0.238% |

| 3×3 | 6670903752021072936960 = c. 6.7×1021 | Felgenhauer/Jarvis[6][14] | Yes | -0.207% |

| 3×4 | 81171437193104932746936103027318645818654720000 = c. 8.1×1046 | Pettersen / Silver[20] | No | -0.132% |

| 3×5 | unknown, estimated c. 3.5086×1084 | Silver[21] | n/a | |

| 4×4 | unknown, estimated c. 5.9584×1098 | Silver[22] | n/a | |

| 4×5 | unknown, estimated c. 3.1764×10175 | Silver[23] | n/a | |

| 5×5 | unknown, estimated c. 4.3648×10308 | Silver / Pettersen[24] | n/a | |

3.2. Sudoku Bands

For large (R,C), the method of Kevin Kilfoil[25] (generalised method:[13]) is used to estimate the number of grid completions. The method asserts that the Sudoku row and column constraints are, to first approximation, conditionally independent given the box constraint. Omitting a little algebra, this gives the Kilfoil-Silver-Pettersen formula:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{Number of Grids} \simeq \frac{b_{R,C}^C \times b_{C,R}^R}{(RC)!^{RC}} }[/math]

where bR,C is the number of ways of completing a Sudoku band[2] of R horizontally adjacent R×C boxes. Petersen's algorithm,[26] as implemented by Silver,[27] is currently the fastest known technique for exact evaluation of these bR,C.

The band counts for problems whose full Sudoku grid-count is unknown are listed below. As in the previous section, "Dimensions" are those of the regions.

| Dimensions | Nr Bands | Attribution | Verified? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2×C | (2C)! (C!)2 | (obvious result) | Yes |

| 3×C | [math]\displaystyle{ (3C)! (C!)^6 \sum_{k=0}^C {C \choose k}^3 }[/math] | Pettersen[16] | Yes |

| 4×C | (long expression: see below) | Pettersen[28] | Yes[29] |

| 4×4 | 16! × 4!12 × 1273431960 = c. 9.7304×1038 | Silver[22] | Yes |

| 4×5 | 20! × 5!12 × 879491145024 = c. 1.9078×1055 | Russell[30] | Yes |

| 4×6 | 24! × 6!12 × 677542845061056 = c. 8.1589×1072 | Russell[30] | Yes |

| 4×7 | 28! × 7!12 × 563690747238465024 = c. 4.6169×1091 | Russell[30] | Yes |

| (calculations up to 4×100 have been performed by Silver,[31] but are not listed here) | |||

| 5×3 | 15! × 3!20 × 324408987992064 = c. 1.5510×1042 | Silver[23] | Yes# |

| 5×4 | 20! × 4!20 × 518910423730214314176 = c. 5.0751×1066 | Silver[23] | Yes# |

| 5×5 | 25! × 5!20 × 1165037550432885119709241344 = c. 6.9280×1093 | Pettersen / Silver[24] | No |

| 5×6 | 30! × 6!20 × 3261734691836217181002772823310336 = c. 1.2127×10123 | Pettersen / Silver[24] | No |

| 5×7 | 35! × 7!20 × 10664509989209199533282539525535793414144 = c. 1.2325×10154 | Pettersen / Silver[32] | No |

| 5×8 | 40! × 8!20 × 39119312409010825966116046645368393936122855616 = c. 4.1157×10186 | Pettersen / Silver[27] | No |

| 5×9 | 45! × 9!20 × 156805448016006165940259131378329076911634037242834944 = c. 2.9406×10220 | Pettersen / Silver[27] | No |

| 5×10 | 50! × 10!20 × 674431748701227492664421138490224315931126734765581948747776 = c. 3.2157×10255 | Pettersen / Silver[27] | No |

- # : same author, different method

The expression for the 4×C case is: [math]\displaystyle{ (4C)!(C!)^{12}\sum_{a, b, c} {\left( \frac{C!^2}{a! b! c!} \cdot \sum_{k_{12},k_{13},k_{14},\atop k_{23},k_{24},k_{34}} {{a\choose k_{12}}{b\choose k_{13}}{c \choose k_{14}}{c \choose k_{23}}{b \choose k_{24}}{a \choose k_{34}} } \right)^2 } }[/math]

where:

- the outer summand is taken over all a,b,c such that 0<=a,b,c and a+b+c=2C

- the inner summand is taken over all k12,k13,k14,k23,k24,k34 ≥ 0 such that

- k12,k34 ≤ a and

- k13,k24 ≤ b and

- k14,k23 ≤ c and

- k12+k13+k14 = a-k12+k23+k24 = b-k13+c-k23+k34 = c-k14+b-k24+a-k34 = C

3.3. Sudoku with Additional Constraints

The following are all restrictions of 3x3 Sudokus. The type names have not been standardised: click on the attribution links to see the definitions.

| Type | Nr Grids | Attribution | Verified? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quasi-Magic Sudoku | 248832 | Jones, Perkins and Roach[33] | Yes |

| 3doku | 104015259648 | Stertenbrink[34] | Yes |

| Disjoint Groups | 201105135151764480 | Russell[35] | Yes |

| Hypercube | 37739520 | Stertenbrink[36] | Yes |

| Magic Sudoku | 5971968 | Stertenbrink[37] | Yes |

| Sudoku X | 55613393399531520 | Russell[38] | Yes |

| NRC Sudoku | 6337174388428800 | Brouwer[39] | Yes |

A Sudoku will remain valid under the actions of the Sudoku preserving symmetries (see also Jarvis[7]). Some Sudokus are special in that some operations merely have the effect of relabelling the digits; several of these are listed below.

| Transformation | Nr Grids | Verified? |

|---|---|---|

| Transposition | 10980179804160 | Indirectly |

| Quarter Turn | 4737761280 | Indirectly |

| Half Turn | 56425064693760 | Indirectly |

| Band cycling | 5384326348800 | Indirectly |

| Within-band row cycling | 39007939461120 | Indirectly |

Further calculations of this ilk combine to show that the number of essentially different Sudoku grids is 5,472,730,538, for example as demonstrated by Jarvis / Russell[7] and verified by Pettersen.[40] Similar methods have been applied to the 2x3 case, where Jarvis / Russell[41] showed that there are 49 essentially different grids (see also the article by Bailey, Cameron and Connelly[42]), to the 2x4 case, where Russell[43] showed that there are 1,673,187 essentially different grids (verified by Pettersen[44]), and to the 2x5 case where Pettersen[45] showed that there are 4,743,933,602,050,718 essentially different grids (not verified).

4. Minimum Number of Givens

Ordinary Sudokus (proper puzzles) have a unique solution. A minimal Sudoku is a Sudoku from which no clue can be removed leaving it a proper Sudoku. Different minimal Sudokus can have a different number of clues. This section discusses the minimum number of givens for proper puzzles.

4.1. Ordinary Sudoku

A Sudoku with 24 clues, dihedral symmetry (symmetry on both orthogonal axis, 90° rotational symmetry, 180° rotational symmetry, and diagonal symmetry) is known to exist, and is also automorphic. Again here, it is not known if this number of clues is minimal for this class of Sudoku.[48][57] The fewest clues in a Sudoku with two-way diagonal symmetry is believed to be 18, and in at least one case such a Sudoku also exhibits automorphism.

4.2. Sudokus of Other Sizes

- 4×4(2×2) Sudoku: The fewest clues in any 4×4 Sudoku is 4, of which there are 13 non-equivalent puzzles. (The total number of non-equivalent minimal Sudokus of this size is 36).[58]

- 6×6(2×3) Sudoku: The fewest clues is 8.[59]

- 8×8(2×4) Sudoku: The fewest clues is 14.[59]

- 10×10(2×5) Sudoku: At least one puzzle with 22 clues has been created.[60] It is not known if this is the fewest possible.

- 12×12(2×6) Sudoku: At least one puzzle with 32 clues has been created.[60] It is not known if this is the fewest possible.

- 12×12(3×4) Sudoku: At least one puzzle with 30 clues has been created.[60] It is not known if this is the fewest possible.

- 15×15(3×5) Sudoku: At least one puzzle with 48 clues has been created.[60] It is not known if this is the fewest possible.

- 16×16(4×4) Sudoku: At least one puzzle with 55 clues has been created.[60] It is not known if this is the fewest possible.

- 25×25(5×5) Sudoku: A puzzle with 151 clues has been created.[61] It is not known if this is the fewest possible.

4.3. Sudoku with Additional Constraints

Additional constraints (here, on 3×3 Sudokus) lead to a smaller minimum number of clues.

- 3doku: no results for this variant

- Disjoint Groups: some 12-clue puzzles[62] have been demonstrated by Glenn Fowler. Later also 11-clue puzzles are found. It is not known if this is the best possible.

- Hypercube: various 8-clue puzzles[63] (the best possible) have been demonstrated by Guenter Stertenbrink.

- Magic Sudoku: a 7-clue example[64] has been provided by Guenter Stertenbrink. It is not known if this is the best possible.

- Sudoku X: a list of 7193 12-clue puzzles[65] has been collected by Ruud van der Werf. It is not known if this is the best possible.

- NRC Sudoku: an 11-clue example[39] has been provided by Andries Brouwer. It is not known if this is the best possible.

- 2-Quasi-Magic Sudoku: a 4-clue example[66] has been provided by Tony Forbes. It is suspected that this is the best possible.

4.4. Sudoku with Irregular Regions

"Du-sum-oh"[67] (a.k.a. "geometry number place") puzzles replace the 3×3 (or R×C) regions of Sudoku with irregular shapes of a fixed size. Bob Harris has proved[68] that it is always possible to create (N − 1)-clue du-sum-ohs on an N×N grid, and has constructed several examples. Johan de Ruiter has proved[69] that for any N>3 there exist polyomino tilings that can not be turned into a Sudoku puzzle with N irregular shapes of size N.

4.5. Sum Number Place ("Killer Sudoku")

In sum number place (Samunampure), the regions are of irregular shape and various sizes. The usual constraints of no repeated value in any row, column or region apply. The clues are given as sums of values within regions (e.g. a 4-cell region with sum 10 must consist of values 1,2,3,4 in some order). The minimum number of clues for Samunampure is not known, nor even conjectured. A variant on Miyuki Misawa's web site[70] replaces sums with relations: the clues are symbols =, < and > showing the relative values of (some but not all) adjacent region sums. She demonstrates an example with only eight relations. It is not known whether this is the best possible.

5. Maximum Number of Givens

The most clues for a minimal Sudoku is believed to be 40, of which only two are known. If any clue is removed from either of these Sudokus, the puzzle would have more than one solution (and thus not be a proper Sudoku). These two Sudokus were discovered in 2014, more than four years after at least one programmer expressed doubts that a 40-clue minimal Sudoku would exist. In the work to find these Sudokus, other high-clue puzzles were catalogued, including more than 6,500,000,000 minimal puzzles with 36 clues. About 2600 minimal Sudokus with 39 clues were also found.[71]

If dropping the requirement for the uniqueness of the solution, 41-clue minimal pseudo-puzzles are known to exist, but they can be completed to more than one solution grid. Removal of any clue increases the number of the completions and from this perspective none of the 41 clues is redundant. With slightly more than half the grid filled with givens (41 of 81 cells), the uniqueness of the solution constraint still dominates over the minimality constraint.[72]

As for the most clues possible in a Sudoku while still not rendering a unique solution, it is four short of a full grid (77). If two instances of two numbers each are missing and the cells they are to occupy are the corners of an orthogonal rectangle, and exactly two of these cells are within one region, there are two ways the last digits can be added (two solutions).

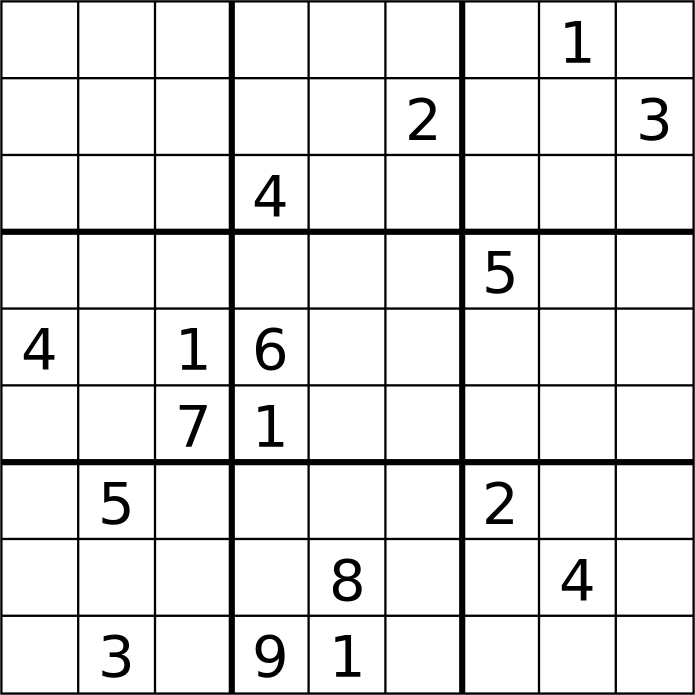

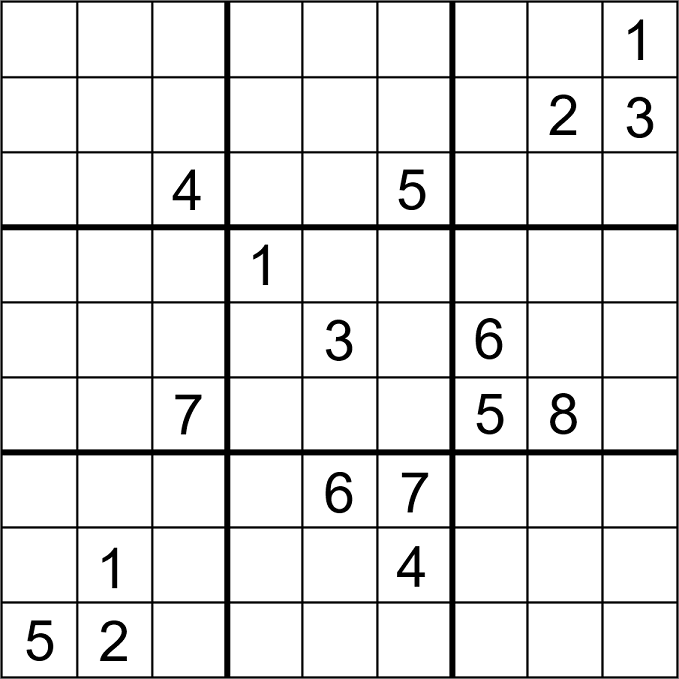

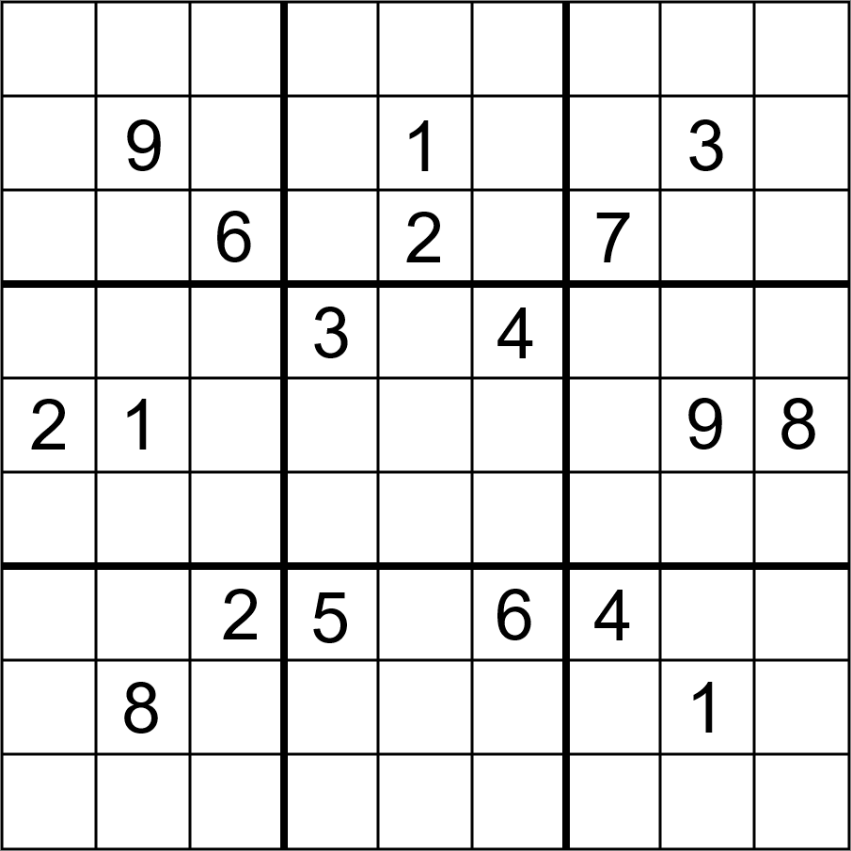

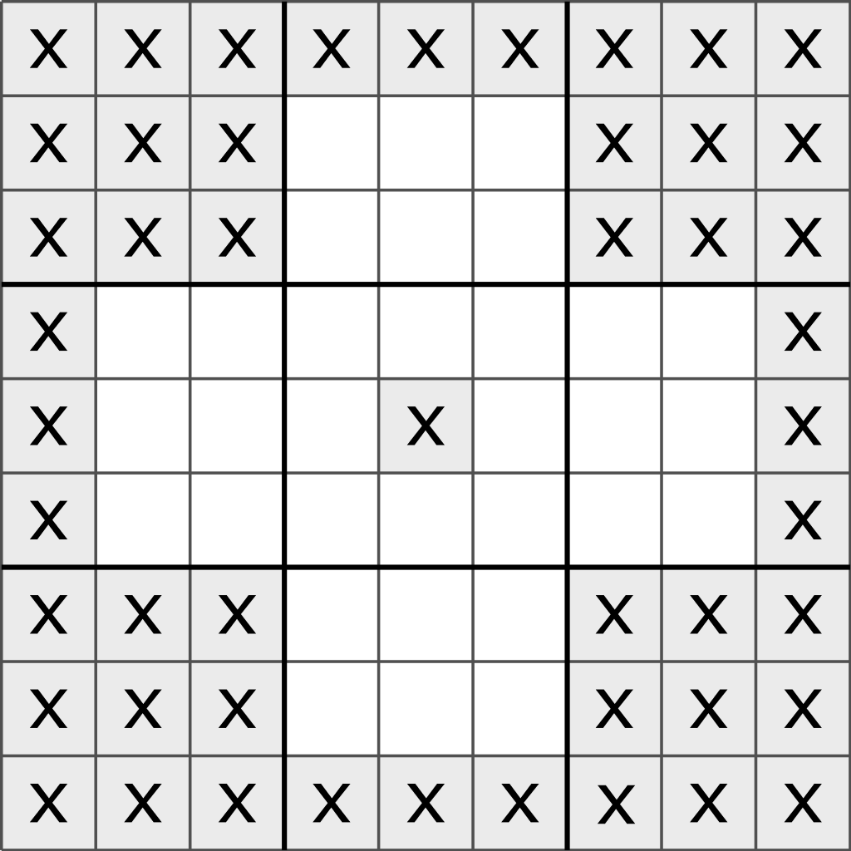

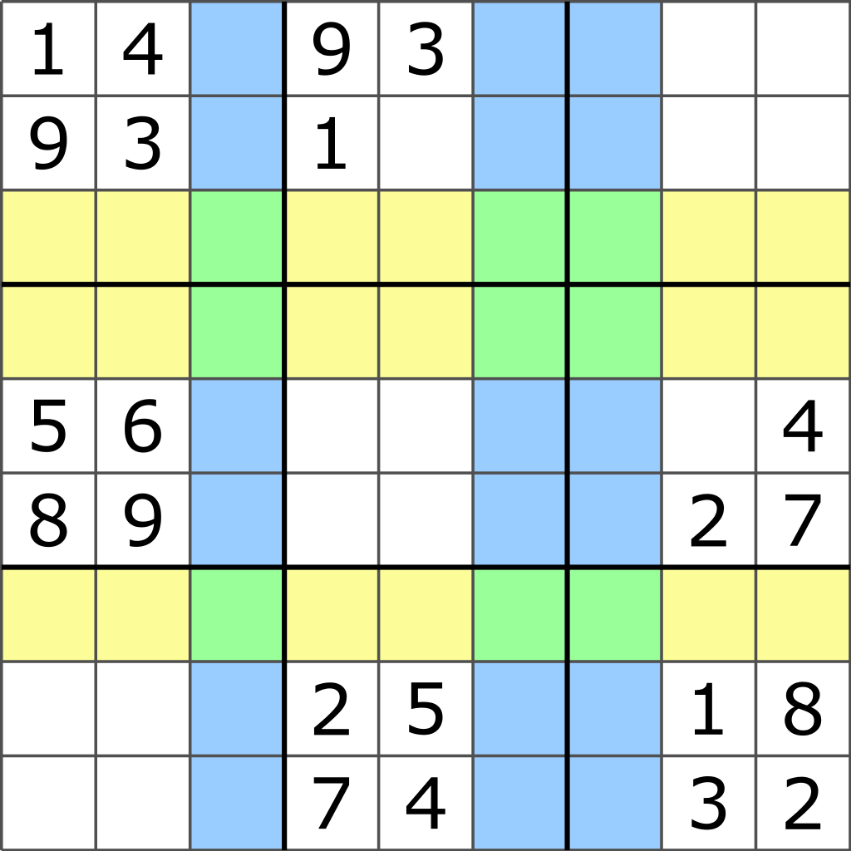

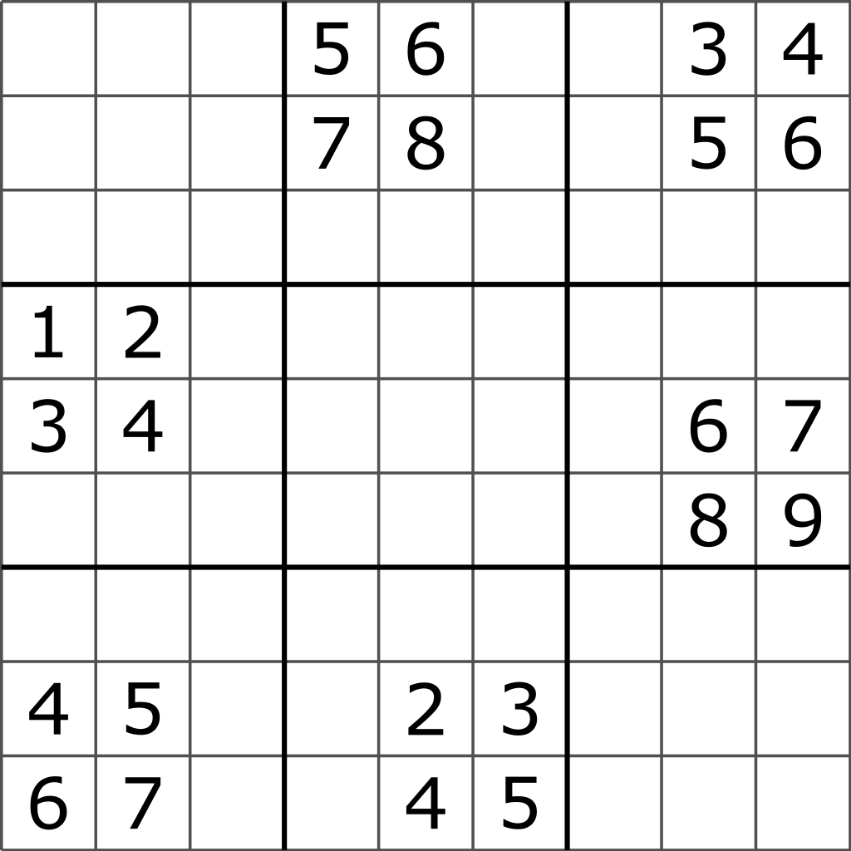

6. Constraints of Clue Geometry

|

|

|

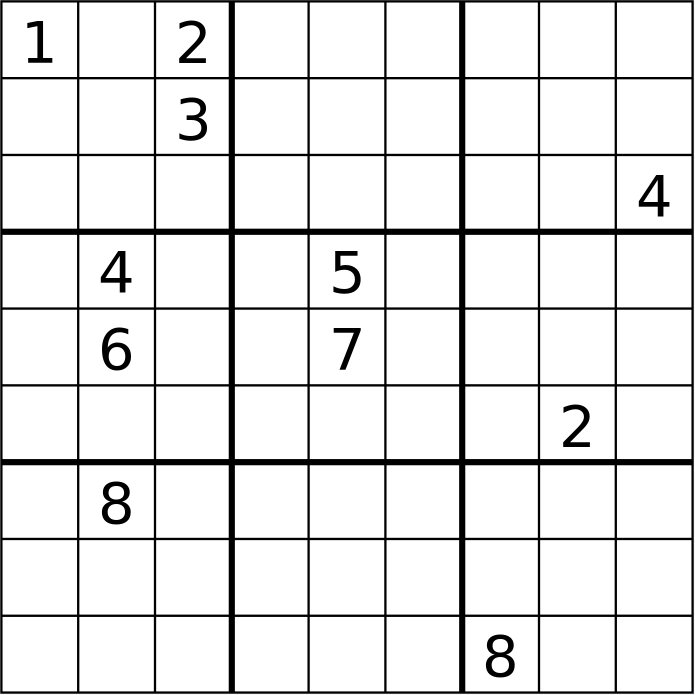

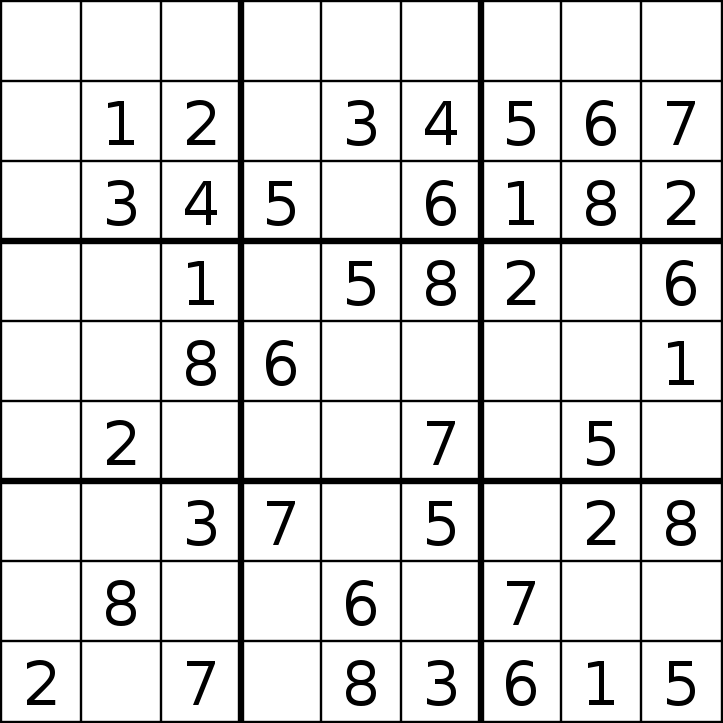

It has been conjectured that no proper Sudoku can have clues limited to the range of positions in the pattern above (first image).[73] The largest rectangular orthogonal "hole" (region with no clues) in a proper Sudoku is believed to be a rectangle of 30 cells (a 5 x 6 rectangular area).[74][75] One example is a Sudoku with 22 clues (second image). The largest total number of empty groups (rows, columns, and boxes) in a Sudoku is believed to be nine. One example is a Sudoku with 3 empty rows, 3 empty columns, and 3 empty boxes (third image).[76][77]

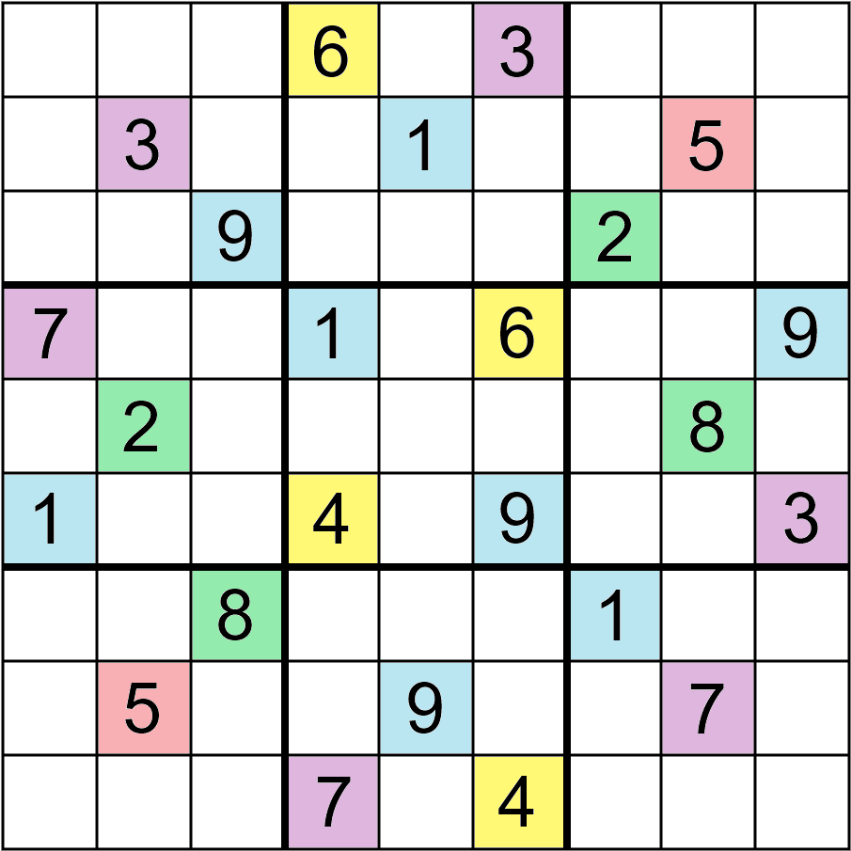

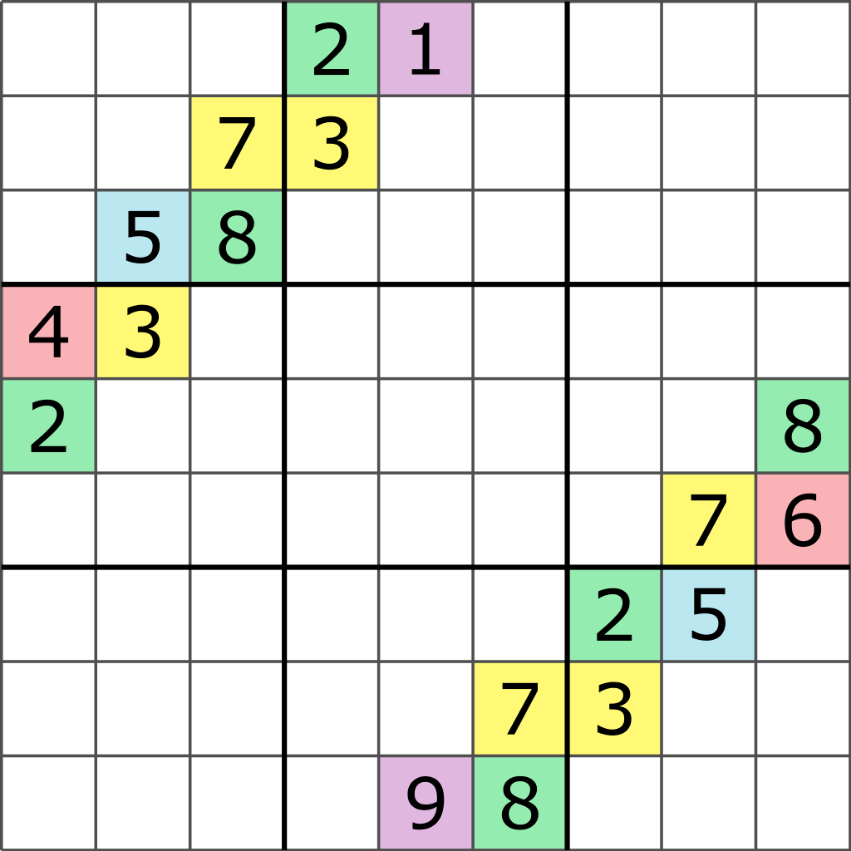

7. Automorphic Sudokus

A Sudoku grid is automorphic if it can be transformed in a way that leads back to the original grid, when that same transformation would not otherwise lead back to the original grid. One example of a grid which is automorphic would be a grid which can be rotated 180 degrees resulting in a new grid where the new cell values are a permutation of the original grid. Automorphic Sudokus are Sudoku puzzles which solve to an automorphic grid. Two examples of automorphic Sudokus, and an automorphic grid are shown below.

|

|

|

| Automorphisms | Nr Grids | Automorphisms | Nr Grids |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5472170387 | 18 | 85 |

| 2 | 548449 | 27 | 2 |

| 3 | 7336 | 36 | 15 |

| 4 | 2826 | 54 | 11 |

| 6 | 1257 | 72 | 2 |

| 8 | 29 | 108 | 3 |

| 9 | 42 | 162 | 1 |

| 12 | 92 | 648 | 1 |

In the first two examples, notice that if the Sudoku is rotated 180 degrees, and the clues relabeled with the permutation (123456789) -> (987654321), it returns to the same Sudoku. Expressed another way, these Sudokus have the property that every 180 degree rotational pair of clues (a, b) follows the rule (a) + (b) = 10.

Since these Sudokus are automorphic, so too their solutions grids are automorphic. Furthermore, every cell which is solved has a symmetrical partner which is solved with the same technique (and the pair would take the form a + b = 10). Notice that in the second example, the Sudouku also exhibits translational (or repetition) symmetry; clues are clustered in groups, with the clues in each group ordered sequentially (i.e., n, n+1, n+2, and n+3).

The third image is the Most Canonical solution grid.[80] This grid has 648 automorphisms and contributes to all ~6.67×1021 solution grids by factor of 1/648 compared to any non-automorphic grid.

In these examples the automorphisms are easy to identify, but in general automorphism is not always obvious. The table at right shows the number of the essentially different Sudoku solution grids for all existing automorphisms.[81]

8. Details of Enumerating Distinct Grids (9×9)

An enumeration technique based on band generation was developed that is significantly less computationally intensive. The strategy begins by analyzing the permutations of the top band used in valid solutions. Once the Band1 symmetries and equivalence class for the partial solutions are identified, the completions of the lower two bands are constructed and counted for each equivalence class.

8.1. Counting the Top Band Permutations

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7 | 8 | 9 |

The Band1 algorithm proceeds as follows:

- Choose a canonical labeling of the digits by assigning values for B1 (see grid), and compute the rest of the Band1 permutations relative B1.

- Compute the permutations of B2 by partitioning the B1 cell values over the B2 row triplets. From the triplet combinations compute the B2 permutations. There are k=0..3 ways to choose the:

- B1 r11 values for B2 r22, the rest must go to r16,

- B1 r12 values for B2 r23, the rest must go to r16,

- B1 r13 values for B2 r21, the rest must go to r16, i.e.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{N combinations for B2} = \sum_{k=0..3}{{3 \choose k}^3} }[/math]

(This expression may be generalized to any R×3 box band variant. (Pettersen[16]). Thus B2 contributes 56 × 63 permutations.

- The choices for B3 triplets are row-wise determined by the B1 B2 row triplets. B3 always contributes 63 permutations.

The permutations for Band1 are 9! × 56 × 66 = 9! × 2612736 ~ 9.48×1011.

Band1 permutation details

Template:Sudoku 3x9 band The permutations of B1 are the number of ways to relabel the 9 digits, 9! = 362880. Counting the permutations for B2 is more complicated, because the choices for B2 depend on the values in B1. (This is a visual representation of the expression given above.) The conditional calculation needs a branch (sub-calculation) for each alternative. Fortunately, there are just 4 cases for the top B2 triplet (r21): it contains either 0, 1, 2, or 3 of the digits from the B1 middle row triplet(r12). Once this B2 top row choice is made, the rest of the B2 combinations are fixed. The Band1 row triplet labels are shown on the right.

(Note: Conditional combinations becomes an increasingly difficult as the computation progresses through the grid. At this point the impact is minimal.) Template:Sudoku 3x9 band Case 0: No Overlap. The choices for the triplets can be determined by elimination.

- r21 can't be r11 or r12 so it must be = r13; r31 must be = r12 etc.

The Case 0 diagram shows this configuration, where the pink cells are triplet values that can be arranged in any order within the triplet. Each triplet has 3! = 6 permutations. The 6 triplets contribute 66 permutations.

Case 3: 3 Digits Match: triplet r21 = r12. The same logic as case 0 applies, but with a different triplet usage. Triplet r22 must be = r13, etc. The number of permutations is again 66 (Felgenhauer/Jarvis).[12] Call the cases 0 and 3 the pure match case. Template:Sudoku 3x9 band Case 1: 1 Match for r21 from r12

In the Case 1 diagram, B1 cells show canonical values, which are color-coded to show their row-wise distribution in B2 triplets. Colors reflect distribution but not location or values. For this case: the B2 top row triplet (r21) has 1 value from B1 middle triplet, the other colorings can now be deduced. E.g. the B2 bottom row triplet (r23) coloring is forced by r21: the other 2 B1 middle values must go to bottom, etc. Fill in the number of B2 options for each color, 3..1, beginning top left. The B3 color-coding is omitted since the B3 choices are row-wise determined by B1, B2. B3 always contributes 3! permutations per row triplet, or 63 for the block.

For B2, the triplet values can appear in any position, so a 3! permutation factor still applies, for each triplet. However, since some of the values were paired relative to their origin, using the raw option counts would overcount the number of permutations, due to interchangeability within the pairing. The option counts need to be divided by the permuted size of their grouping (2), here 2!.= 2 (See n Choose k) The pair in each row cancels the 2s for the B2 option counts, leaving a B2 contribution of 33 × 63. The B2×B3 combined contribution is 33 × 66. Template:Sudoku 3x9 band Case 2: 2 Matches for r21 from r12. The same logic as case 1 applies, but with the B2 option count column groupings reversed. Case 3 also contributes 33×66 permutations.

Totaling the 4 cases for Band1 B1..B3 gives 9! × 2 × (33 + 1) × 66 = 9! 56 × 66 permutations.

8.2. Band1 Symmetries and Equivalence Classes

Symmetries are used to reduce the computational effort to enumerate the Band1 permutations. A symmetry is an operation that preserves a quality of an object. For a Sudoku grid, a symmetry is a transformation whose result is also a valid grid. The following symmetries apply independently for the top band:

- Block B1 values may be relabeled, giving 9! permutations

- Blocks B1..3 may be interchanged, with 3!=6 permutations

- Rows 1..3 may be interchanged, with 3!=6 permutations

- Within each block, the 3 columns may be interchanged, giving 3!3 = 63 permutations.

Combined, the symmetries give 9! × 65 = 362880 × 7776 equivalent permutations for each Band1 solution.

A symmetry defines an equivalence relation, here, between the solutions, and partitions the solutions into a set of equivalence classes. The Band1 row, column and block symmetries divide the 56*6^6 permutations into (not less than) 336 (56×6) equivalence classes with (up to) 65 permutations in each, and 9! relabeling permutations for each class. (Min/Max caveats apply since some permutations may not yield distinct elements due to relabeling.)

Since the solution for any member of an equivalence class can be generated from the solution of any other member, we only need to enumerate the solutions for a single member in order to enumerate all solutions over all classes. Let

- sb : be a valid permutation of the top band

- Sb = [sb] : be an equivalence class, relative to sb and some equivalence relation

- Sb.z = |Sb| : the size of Sb, be the number of sb elements (permutations) in [sb]

- Sb.n : be the number of Band2,3 completions for (any) sb in Sb

- {Sb} : be the set of all Sb equivalence classes relative to the equivalence relation

- {Sb}.z = |{Sb}| : be the number of equivalence classes

The total number of solutions N is then:

- [math]\displaystyle{ N = \sum_{\{Sb\}} \mbox{Sb.z} \times \mbox{Sb.n} }[/math]

Solution and counting permutation symmetry

The Band1 symmetries (above) are solution permutation symmetries defined so that a permuted solution is also a solution. For the purpose of enumerating solutions, a counting symmetry for grid completion can be used to define band equivalence classes that yield a minimal number of classes.

Counting symmetry partitions valid Band1 permutations into classes that place the same completion constraints on lower bands; all members of a band counting symmetry equivalence class must have the same number of grid completions since the completion constraints are equivalent. Counting symmetry constraints are identified by the Band1 column triplets (a column value set, no implied element order). Using band counting symmetry, a minimal generating set of 44 equivalence classes[82] was established.

The following sequence demonstrates mapping a band configuration to a counting symmetry equivalence class. Begin with a valid band configuration (1). Build column triplets by ordering the column values within each column. This is not a valid Sudoku band, but does place the same constraints on the lower bands as the example (2). Construct an equivalence class ID from the B2, B3 column triplet values. Use column and box swaps to achieve the lowest lexicographical ID. The last figure shows the column and box ordering for the ID: 124 369 578 138 267 459. All Band1 permutations with this counting symmetry ID will have the same number of grid completions as the original example. An extension of this process can be used to build the largest possible band counting symmetry equivalence classes (3).

Note, while column triplets are used to construct and identify the equivalence classes, the class members themselves are the valid Band1 permutations: class size (Sb.z) reflects column triplet permutations compatible with the One Rule solution requirements. Counting symmetry is a completion property and applies only to a partial grid (band or stack). Solution symmetry for preserving solutions can be applied to either partial grids (bands, stacks) or full grid solutions. Lastly note, counting symmetry is more restrictive than simple numeric completion count equality: two (distinct) bands belong to the same counting symmetry equivalence class only if they impose equivalent completion constraints.

Band 1 reduction details

Symmetries group similar object into equivalence classes. Two numbers need to be distinguished for equivalence classes, and band symmetries as used here, a third:

- the number of equivalence classes ({Sb}.n).

- the cardinality, size or number of elements in an equivalence class, which may vary by class (Sb.z)

- the number of Band2,3 completions compatible with a member of a Band1 equivalence class (Sb.n)

The Band1 (65) symmetries divide the (56×66) Band1 valid permutations into (not less than) 336 (56×6) equivalence classes with (up to) 6^5 permutations each. The not less than and up to caveats are necessary, since some combinations of the transformations may not produce distinct results, when relabeling is required (see below). Consequently, some equivalence classes may contain less than 65 distinct permutations and the theoretical minimum number of classes may not be achieved.

Each of the valid Band1 permutations can be expanded (completed) into a specific number of solutions with the Band2,3 permutations. By virtue of their similarity, each member of an equivalence class will have the same number of completions. Consequently, we only need to construct the solutions for one member of each equivalence class and then multiply the number of solutions by the size of the equivalence class. We are still left with the task of identifying and calculating the size of each equivalence class. Further progress requires the dexterous application of computational techniques to catalogue (classify and count) the permutations into equivalence classes.

Felgenhauer/Jarvis[12] catalogued the Band1 permutations using lexicographical ordered IDs based on the ordered digits from blocks B2,3. Block 1 uses a canonical digit assignment and is not needed for a unique ID. Equivalence class identification and linkage uses the lowest ID within the class.

Application of the (2×62) B2,3 symmetry permutations produces 36288 (28×64) equivalence classes, each of size 72. Since the size is fixed, the computation only needs to find the 36288 equivalence class IDs. (Note: in this case, for any Band1 permutation, applying these permutations to achieve the lowest ID provides an index to the associated equivalence class.)

Application of the rest of the block, column and row symmetries provided further reduction, i.e. allocation of the 36288 IDs into fewer, larger equivalence classes. When the B1 canonical labeling is lost through a transformation, the result is relabeled to the canonical B1 usage and then catalogued under this ID. This approach generated 416 equivalence classes, somewhat less effective than the theoretical 336 minimum limit for a full reduction. Application of counting symmetry patterns for duplicate paired digits achieved reduction to 174 and then to 71 equivalence classes. The introduction of equivalence classes based on band counting symmetry (subsequent to Felgenhauer/Jarvis by Russell[82]) reduced the equivalence classes to a minimum generating set of 44.

The diversity of the ~2.6×106, 56×66 Band1 permutations can be reduced to a set of 44 Band1 equivalence classes. Each of the 44 equivalence classes can be expanded to millions of distinct full solutions, but the entire solution space has a common origin in these 44. The 44 equivalence classes play a central role in other enumeration approaches as well, and speculation will return to the characteristics of the 44 classes when puzzle properties are explored later.

8.3. Band 2-3 Completion and Results

Enumerating the Sudoku solutions breaks into an initial setup stage and then into two nested loops. Initially all the valid Band1 permutations are grouped into equivalence classes, who each impose a common constraint on the Band2,3 completions. For each of the Band1 equivalence classes, all possible Band2,3 solutions need to be enumerated. An outer Band1 loop iterates over the 44 equivalence classes. In the inner loop, all lower band completions for each of the Band1 equivalence class are found and counted.

The computation required for the lower band solution search can be minimised by the same type of symmetry application used for Band1. There are 6! (720) permutations for the 6 values in column 1 of Band2,3. Applying the lower band (2) and row within band (6×6) permutations creates 10 equivalence classes of size 72. At this point, completing 10 sets of solutions for the remaining 48 cells with a recursive descent, backtracking algorithm is feasible with 2 GHz class PC so further simplification is not required to carry out the enumeration. Using this approach, the number of ways of filling in a blank Sudoku grid has been shown to be 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 (6.67×1021).[12]

The result, as confirmed by Russell,[82] also contains the distribution of solution counts for the 44 equivalence classes. The listed values are before application of the 9! factor for labeling and the two 72 factors (722 = 5184) for each of Stack 2,3 and Band2,3 permutations. The number of completions for each class is consistently on the order of 100,000,000, while the number of Band1 permutations covered by each class however varies from 4 – 3240. Within this wide size range, there are clearly two clusters. Ranked by size, the lower 33 classes average ~400 permutations/class, while the upper 11 average ~2100. The disparity in consistency between the distributions for size and number of completions or the separation into two clusters by size is yet to be examined.

9. Variants

Sudoku regions are polyominoes. Although the classic 9×9 Sudoku is made of square nonominoes, it is possible to apply the rules of Sudoku to puzzles of other sizes – the 2×2 and 4×4 square puzzles, for example. Only N2×N2 Sudoku puzzles can be tiled with square polyominoes. Another popular variant is made of rectangular regions – for example, 2×3 hexominoes tiled in a 6×6 grid. The following notation is used for discussing this variant.

- R×C denotes a rectangular region with R rows and C columns.

- The implied grid configuration has:

- C blocks per band,

- R blocks per stack,

- C×R bands×stacks,

- an arrangement of C×R regions, and

- grid dimensions N×N, where N = R×C.

Puzzles of size N×N, where N is prime can only be tiled with irregular N-ominoes. Each N×N grid can be tiled multiple ways with N-ominoes. Before enumerating the number of solutions to a Sudoku grid of size NxN, it is necessary to determine how many N-omino tilings exist for a given size (including the standard square tilings, as well as the rectangular tilings).

The size ordering of Sudoku puzzle can be used to define an integer series, e.g. for square Sudoku, the integer series of possible solutions (sequence A107739 in the OEIS). Sudoku with square N×N regions are more symmetrical than immediately obvious from the One Rule. Each row and column intersects N regions and shares N cells with each. The number of bands and stacks also equals N. Rectangular Sudoku do not have these properties. The "3×3" Sudoku is additionally unique: N is also the number of row-column-region constraints from the One Rule (i.e. there are N=3 types of units). See the Glossary of Sudoku for an expanded list of variants.

References

- Lin, Keh Ying (2004), "Number Of Sudokus", Journal of Recreational Mathematics 33 (2): 120–24 .

- "Basic terms : About the New Sudoku Players' Forum". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. 16 May 2006. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/viewtopic.php?t=4120. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Berthier, Denis (November 2007). The Hidden Logic of Sudoku (Second, revised and extended ed.). Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-84799-214-7. http://denis.berthier.pagesperso-orange.fr/HLS/index.html. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- "NP complete – Sudoku". Imai.is.su-tokyo.ac.jp. http://www-imai.is.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~yato/data2/SIGAL87-2.pdf. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Lewis, R. A Guide to Graph Colouring: Algorithms and Applications. Springer International Publishers, 2015.

- "Sudoku enumeration problems". Afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk. http://www.afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk/sudoku. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "Sudoku enumeration: the symmetry group". Afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk. 7 September 2005. http://www.afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk/sudoku/sudgroup.html. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Berthier, Denis (4 December 2009). "Unbiased Statistics of a CSP – A Controlled-Bias Generator". http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00641955. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- "Counting minimal puzzles: subsets, supersets, etc.". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. 2013-06-11. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/counting-minimal-puzzles-subsets-supersets-etc-t31190.html. Retrieved 2017-04-18.

- "Google Discussiegroepen". Groups.google.com. https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/rec.puzzles/A7pi7S12oFI. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "6670903752021072936960 is old hat : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/6670903752021072936960-is-old-hat-t5871.html. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- Felgenhauer, Bertram; Jarvis, Frazer (June 20, 2005), Enumerating possible Sudoku grids, http://www.afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk/sudoku/sudoku.pdf .

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 36". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post15920.html#p15920. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- Sloane, N. J. A., ed. "Sequence A107739 (Number of (completed) sudokus (or Sudokus) of size n^2 X n^2)". OEIS Foundation. https://oeis.org/A107739. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Sudoku maths - can mortals work it out for the 2x2 square ? : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post2992.html#p2992. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 28". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post11444.html#p11444. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 29". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post11874.html#p11874. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 29". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post12191.html#p12191. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "6x2 counting : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/viewtopic.php?p=37761#p37761. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "4x3 Sudoku counting : General - Page 2". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post25773.html#p25773. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 38". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post17768.html#p17768. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 36". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post15909.html#p15909. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 38". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post17750.html#p17750. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "RxC Sudoku band counting algorithm : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post19318.html#p19318. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 3". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post788.html#p788. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "RxC Sudoku band counting algorithm : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post18161.html#p18161. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "RxC Sudoku band counting algorithm : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post20867.html#p20867. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 37". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post16169.html#p16169. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "RxC Sudoku band counting algorithm : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post18396.html#p18396. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 37". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post16071.html#p16071. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "RxC Sudoku band counting algorithm : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post21245.html#p21245. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "RxC Sudoku band counting algorithm : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post19416.html#p19416. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Properties, isomorphisms and enumeration of 2-Quasi-Magic Sudoku grids". Discrete Mathematics 311: 1098–1110. 2011-07-06. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2010.09.026. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012365X10003778. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 27". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post11088.html#p11088. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 13". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post2536.html#p2536. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 27". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post11216.html#p11216. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Sudoku Programmers :: View topic - Number of "magic sudokus" (and random generation)". Setbb.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120206221359/http://www.setbb.com/phpbb/viewtopic.php?t=366&mforum=sudoku. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Calling all sudoku experts : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post3366.html#p3366. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "NRC Sudokus". Homepages.cwi.nl. http://homepages.cwi.nl/~aeb/games/sudoku/nrc.html. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Su-Doku's maths : General - Page 31". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post13388.html#p13388. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Sudoku enumeration 2x3: the symmetry group". Afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk. http://www.afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk/sudoku/sud23gp.html. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "Sudoku". Maths.qmul.ac.uk. http://www.maths.qmul.ac.uk/~pjc/preprints/sudoku.pdf. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Sudoku enumeration 2x4: the symmetry group". Afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk. http://www.afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk/sudoku/sud24gp.html. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "Number of essentially different Sudoku grids : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post29983.html#p29983. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Number of essentially different Sudoku grids : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post32483.html#p32483. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Symmetrical 17 Clue Puzzle" Symmetrical 17 Clue Puzzle. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/2599486458

- "Raphael - 18 Clue Symmetrical" Raphael - an 18 clue Sudoku with orthogonal symmetry. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/3029170798

- "Total symmetry" Total symmetry - a 24 clue Sudoku with total symmetry. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/2828956005

- "Tourmaline - 19 Clue Two-Way Symmetry" Tourmaline - a 19 clue Sudoku with two-way orthogonal symmetry. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/3339872043

- "プログラミングパズル雑談コーナー". .ic-net.or.jp. http://www2.ic-net.or.jp/~takaken/auto/guest/bbs46.html. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "Minimum Sudoku". Csse.uwa.edu.au. http://www.csse.uwa.edu.au/~gordon/sudokumin.php. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Yirka, Bob (6 January 2012). "Mathematicians Use Computer to Solve Minimum Sudoku Solution Problem". PhysOrg. http://www.physorg.com/news/2012-01-mathematicians-minimum-sudoku-solution-problem.html. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- McGuire, Gary (1 January 2012). There is no 16-Clue Sudoku: Solving the Sudoku Minimum Number of Clues Problem. http://www.math.ie/checker.html.

- G. McGuire, B. Tugemann, G. Civario. "There is no 16-Clue Sudoku: Solving the Sudoku Minimum Number of Clues Problem". Arxiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1201.0749

- H.H. Lin, I-C. Wu. "No 16-clue Sudoku puzzles by sudoku@vtaiwan project" , September, 2013. http://sudoku.nctu.edu.tw

- "Symmetrically-clued 17s". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/symmetrically-clued-17s-t3570.html. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- "Taking Sudoku seriously", Math Horizons 15 (1): 5–9, 2007 . See in particular Figure 7, p. 7.

- http://forum.enjoysudoku.com The New Sudoku Players' Forum. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/my-4-year-old-is-doing-sudoku-t30643.html#p219790

- [1] Minimal number of clues for Sudokus

- http://forum.enjoysudoku.com Minimum givens on larger puzzles. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/minimum-givens-on-larger-puzzles-t4801.html

- とん (January 2015) (in japanese) (2 ed.). 暗黒通信団. ISBN 978-4873102238. http://mikaka.org/~kana/.

- "Minimum number of clues in Sudoku DG : Sudoku variants". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post22062.html#p22062. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "100 randomized minimal sudoku-like puzzles with 6 constraints". Magictour.free.fr. http://magictour.free.fr/sudoku6. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Number of "magic sudokus" (and random generation) : General - Page 2". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post13320.html#p13320. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Minimum Sudoku-X Collection". Sudocue.net. http://www.sudocue.net/minx.php. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Download Attachment". Anthony.d.forbes.googlepages.com. http://anthony.d.forbes.googlepages.com/M215qm.pdf. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Du-Sum-Oh Puzzles". Bumblebeagle.org. http://www.bumblebeagle.org/dusumoh/9x9/index.html. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Du-Sum-Oh Puzzles". Bumblebeagle.org. http://www.bumblebeagle.org/dusumoh/proof/index.html. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Universiteit Leiden Opleiding Informatica : Internal Report 2010-4 : March 2010". Liacs.nl. http://www.liacs.nl/assets/Bachelorscripties/10-04-JohandeRuiter.pdf. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- [2]

- http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/high-clue-tamagotchis High clue tamagotchis (forum: pages 1-14; 40 clue minimal: page 10). http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/high-clue-tamagotchis-t30020-135.html

- http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/high-clue-tamagotchis High clue tamagotchis (forum: page 5). http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/high-clue-tamagotchis-t30020.html

- "Ask for some patterns that they don't have puzzles. : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/viewtopic.php?t=5384&postdays=0&postorder=asc&start=0. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Largest 'hole' in a Sudoku; Largest 'emtpy space' : General". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/viewtopic.php?t=4209. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Large Empty Space | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 2008-05-06. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/2471768905/. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Largest number of empty groups? : General - Page 2". Forum.enjoysudoku.com. http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post7486.html#p7486. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Clues Bunched in Clusters | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 2008-03-25. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/2361922691/. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "18 Clue Automorphic Sudoku" 18 Clue Automorphic Sudoku. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/2691474926

- "Six Dots with 5 x 5 Empty Hole | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 2008-07-01. https://www.flickr.com/photos/npcomplete/2629305621/. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- http://sudopedia.enjoysudoku.com/Canonical_Form "Canonical Form". http://sudopedia.enjoysudoku.com/Canonical_Form.html

- Fowler, Glenn (2007-02-15). "Number of automorphisms for any grid". http://forum.enjoysudoku.com/post41438.html#p41438. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- "Summary of method and results". Afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk. http://www.afjarvis.staff.shef.ac.uk/sudoku/ed44.html. Retrieved 20 October 2013.