| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rita Xu | -- | 4562 | 2022-10-12 01:33:08 |

Video Upload Options

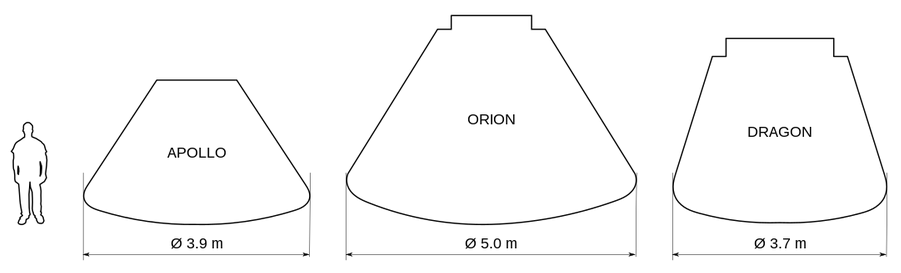

Dragon, also known as Dragon 1 or Cargo Dragon, was a class of partially reusable cargo spacecraft developed by SpaceX, an American private space transportation company. Dragon was launched into orbit by the company's Falcon 9 launch vehicle to resupply the International Space Station (ISS). During its maiden flight in December 2010, Dragon became the first commercially built and operated spacecraft to be recovered successfully from orbit. On 25 May 2012, a cargo variant of Dragon became the first commercial spacecraft to successfully rendezvous with and attach to the ISS. SpaceX is contracted to deliver cargo to the ISS under NASA's Commercial Resupply Services program, and Dragon began regular cargo flights in October 2012. With the Dragon spacecraft and the Orbital ATK Cygnus, NASA seeks to increase its partnerships with domestic commercial aviation and aeronautics industry. On 3 June 2017, the C106 capsule, largely assembled from previously flown components from the CRS-4 mission in September 2014, was launched again for the first time on CRS-11, with the hull, structural elements, thrusters, harnesses, propellant tanks, plumbing and many of the avionics reused, while the heat shield, batteries and components exposed to sea water upon splashdown for recovery were replaced. SpaceX developed a second version called Dragon 2, which is capable of transporting humans. Flight testing was completed in 2019, after a delay caused by a test pad anomaly in April 2019, which resulted in the loss of a Dragon 2 capsule. The first flight of astronauts on Dragon 2 occurred on the Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission in May 2020. The last flight of the first version of the Dragon spacecraft (Dragon 1) launched 7 March 2020 (UTC); it was a cargo resupply mission (CRS-20) to International Space Station (ISS). This mission was the last mission of SpaceX of the first Commercial Resupply Services (CRS-1) program, and marked the retirement of the Dragon 1 fleet. Further SpaceX commercial resupply flights to ISS under the second Commercial Resupply Services (CRS-2) program use the cargo-carrying variant of the SpaceX Dragon 2 spacecraft.

1. Name

SpaceX's CEO, Elon Musk, named the spacecraft after the 1963 song "Puff, the Magic Dragon" by Peter, Paul and Mary, reportedly as a response to critics who considered his spaceflight projects impossible.[1]

2. History

SpaceX began developing the Dragon space capsule in late 2004, making a public announcement in 2006 with a plan of entering service in 2009.[2] Also in 2006, SpaceX won a contract to use the Dragon space capsule for commercial resupply services to the International Space Station for the American federal space agency, NASA.[3]

2.1. NASA ISS Resupply Contract

Commercial Orbital Transportation Services

In 2005, NASA solicited proposals for a commercial ISS resupply cargo vehicle to replace the then-soon-to-be-retired Space Shuttle, through its Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) development program. The Dragon space capsule was a part of SpaceX's proposal, submitted to NASA in March 2006. SpaceX's COTS proposal was issued as part of a team, which also included MD Robotics, the Canadian company that had built the ISS's Canadarm2.

On 18 August 2006, NASA announced that SpaceX had been chosen, along with Kistler Aerospace, to develop cargo launch services for the ISS.[3] NASA later re-awarded Kistler's contract to Orbital Sciences Corporation.[4][5]

Commercial Resupply Services Phase 1

On 23 December 2008, NASA awarded a US$1.6 billion Commercial Resupply Services (CRS-1) contract to SpaceX, with contract options that could potentially increase the maximum contract value to US$3.1 billion.[6] The contract called for 12 flights, with an overall minimum of 20,000 kilograms (44,000 lb) of cargo to be carried to the ISS.[6]

On 23 February 2009, SpaceX announced that its chosen phenolic-impregnated carbon ablator heat shield material, PICA-X, had passed heat stress tests in preparation for Dragon's maiden launch.[7][8] The primary proximity-operations sensor for the Dragon spacecraft, the DragonEye, was tested in early 2009 during the STS-127 mission, when it was mounted near the docking port of the Space Shuttle Endeavour and used while the Shuttle approached the International Space Station. The DragonEye's lidar and thermography (thermal imaging) abilities were both tested successfully.[9][10] The COTS UHF Communication Unit (CUCU) and Crew Command Panel (CCP) were delivered to the ISS during the late 2009 STS-129 mission.[11] The CUCU allows the ISS to communicate with Dragon and the CCP allows ISS crew members to issue basic commands to Dragon.[11] In summer 2009, SpaceX hired former NASA astronaut Ken Bowersox as vice president of their new Astronaut Safety and Mission Assurance Department, in preparation for crews using the spacecraft.[12]

As a condition of the NASA CRS contract, SpaceX analyzed the orbital radiation environment on all Dragon systems, and how the spacecraft would respond to spurious radiation events. That analysis and the Dragon design – which uses an overall Fault tolerance triple redundant computer architecture, rather than individual radiation hardening of each computer processor – was reviewed by independent experts before being approved by NASA for the cargo flights.[13]

During March 2015, it was announced that SpaceX had been awarded an additional three missions under Commercial Resupply Services Phase 1.[14] These additional missions are SpaceX CRS-13, SpaceX CRS-14 and SpaceX CRS-15 and would cover the cargo needs of 2017. On 24 February 2016, SpaceNews disclosed that SpaceX had been awarded a further five missions under Commercial Resupply Services Phase 1.[15] This additional tranche of missions had SpaceX CRS-16 and SpaceX CRS-17 manifested for FY2017 while SpaceX CRS-18, SpaceX CRS-19 and SpaceX CRS-20 and were notionally manifested for FY2018.

Commercial Resupply Services Phase 2

The Commercial Resupply Services-2 (CRS-2) contract definition and solicitation period commenced in 2014. In January 2016, NASA awarded contracts to SpaceX, Orbital ATK, and Sierra Nevada Corporation for a minimum of six launches each, with missions planned until at least 2024. The maximum potential value of all the contracts was announced as US$14 billion, but the minimum requirements would be considerably less.[16] No further financial information was disclosed.

CRS-2 launches began in late 2019.

Demonstration Flights

The first flight of the Falcon 9, a private flight, occurred in June 2010 and launched a stripped-down version of the Dragon capsule. This Dragon Spacecraft Qualification Unit had initially been used as a ground test bed to validate several of the capsule's systems. During the flight, the unit's primary mission was to relay aerodynamic data captured during the ascent.[17][18] It was not designed to survive re-entry, and did not.

NASA contracted for three test flights from SpaceX, but later reduced that number to two. The first Dragon spacecraft launched on its first mission – contracted to NASA as COTS Demo Flight 1 – on 8 December 2010, and was successfully recovered following re-entry to Earth's atmosphere. The mission also marked the second flight of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle.[19] The DragonEye sensor flew again on STS-133 in February 2011 for further on-orbit testing.[20] In November 2010, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) had issued a re-entry license for the Dragon capsule, the first such license ever awarded to a commercial vehicle.[21]

The second Dragon flight, also contracted to NASA as a demonstration mission, launched successfully on 22 May 2012, after NASA had approved SpaceX's proposal to combine the COTS 2 and 3 mission objectives into a single Falcon 9/Dragon flight, renamed COTS 2+.[22][23] Dragon conducted orbital tests of its navigation systems and abort procedures, before being grappled by the ISS' Canadarm2 and successfully berthing with the station on 25 May 2012 to offload its cargo.[24][25][26][27][28] Dragon returned to Earth on 31 May 2012, landing as scheduled in the Pacific Ocean, and was again successfully recovered.[29][30]

On 23 August 2012, NASA Administrator Charles Bolden announced that SpaceX had completed all required milestones under the COTS contract, and was cleared to begin operational resupply missions to the ISS.[31]

Returning Research Materials from Orbit

Dragon spacecraft can return 3,500 kilograms (7,700 lb) of cargo to Earth, which can be all unpressurized disposal mass, or up to 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb) of pressurized cargo, from the ISS,[32] and is the only current spacecraft capable of returning to Earth with a significant amount of cargo. Other than the Russian Soyuz crew capsule, Dragon is the only currently operating spacecraft designed to survive re-entry. Because Dragon allows for the return of critical materials to researchers in as little as 48 hours from splashdown, it opens the possibility of new experiments on ISS that can produce materials for later analysis on ground using more sophisticated instrumentation. For example, CRS-12 returned mice that have spent time in orbit which will help give insight into how microgravity impacts blood vessels in both the brain and eyes, and in determining how arthritis develops.[33]

Operational Flights

Dragon was launched on its first operational CRS flight on 8 October 2012,[34] and completed the mission successfully on 28 October 2012.[35] NASA initially contracted SpaceX for 12 operational missions, and later extended the CRS contract with 8 more flights, bringing the total to 20 launches until 2019. In 2016, a new batch of 6 missions under the CRS-2 contract was assigned to SpaceX; those missions are scheduled to be launched between 2020 and 2024.

Reuse of Previously-Flown Capsules

CRS-11, SpaceX's eleventh CRS mission, was successfully launched on 3 June 2017 from Kennedy Space Center LC-39A, being the 100th mission to be launched from that pad. This mission was the first to re-fly a previously flown Dragon capsule. This mission delivered 2,708 kilograms[36] of cargo to the International Space Station, including Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER).[37] The first stage of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle landed successfully at Landing Zone 1. This mission launched for the first time a refurbished Dragon capsule,[38] serial number C106, which had flown in September 2014 on the CRS-4 mission,[39] and was the first time since 2011 a reused spacecraft arrived at the ISS.[40] Gemini SC-2 capsule is the only other reused capsule, but it was only reflown suborbitally in 1966.

CRS-12, SpaceX's twelfth CRS mission, was successfully launched on the first "Block 4" version of the Falcon 9 on 14 August 2017 from Kennedy Space Center LC-39A at the first attempt. This mission delivered 2,349 kilograms (5,179 lb) of pressurized mass and 961 kilograms (2,119 lb) unpressurized. The external payload manifested for this flight was the CREAM cosmic-ray detector. Last flight of a newly built Dragon capsule; further missions will use refurbished spacecraft.[41]

CRS-13, SpaceX's thirteenth CRS mission, was the second use of a previously-flown Dragon capsule, but the first time in concordance with a reused first-stage booster. It was successfully launched on 15 December 2017 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 40 at the first attempt. This was the first launch from SLC-40 since the Amos-6 pad anomaly. The booster was the previously-flown core from the CRS-11 mission. This mission delivered 1,560 kilograms (3,440 lb) of pressurized mass and 645 kilograms (1,422 lb) unpressurized. It returned from orbit and splashdown on 13 January 2018, making it the first space capsule to be reflown to orbit more than once.[42]

CRS-14, SpaceX's fourteenth CRS mission, was the third reuse of a previously-flown Dragon capsule. It was successfully launched on 2 April 2018 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station SLC-40. It was successfully berthed to the ISS on 4 April 2018 and remained berthed for a month before returning cargo and science experiments back to Earth.

CRS-15, CRS-16, CRS-17, CRS-18, CRS-19, and CRS-20 were all flown with previously flown capsules.

2.2. Crewed Development Program

In 2006, Elon Musk stated that SpaceX had built "a prototype flight crew capsule, including a thoroughly tested 30-man-day life-support system".[2] A video simulation of the launch escape system's operation was released in January 2011.[43] Musk stated in 2010 that the developmental cost of a crewed Dragon and Falcon 9 would be between US$800 million and US$1 billion.[44] In 2009 and 2010, Musk suggested on several occasions that plans for a crewed variant of the Dragon were proceeding and had a two-to-three-year timeline to completion.[45][46] SpaceX submitted a bid for the third phase of CCDev, CCiCap.[47][48]

3. Development Funding

In 2014, SpaceX released the total combined development costs for both the Falcon 9 launch vehicle and the Dragon capsule. NASA provided US$396 million while SpaceX provided over US$450 million to fund both development efforts.[49]

4. Production

In December 2010, the SpaceX production line was reported to be manufacturing one new Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 rocket every three months. Elon Musk stated in a 2010 interview that he planned to increase production turnover to one Dragon every six weeks by 2012.[50] Composite materials are extensively used in the spacecraft's manufacture to reduce weight and improve structural strength.[51]

By September 2013, SpaceX total manufacturing space had increased to nearly 1,000,000 square feet (93,000 m2) and the factory had six Dragons in various stages of production. SpaceX published a photograph showing the six, including the next four NASA Commercial Resupply Services (CRS-1) mission Dragons (CRS-3, CRS-4, CRS-5, CRS-6) plus the drop-test Dragon, and the pad-abort Dragon weldment for commercial crew program.[52]

5. Design

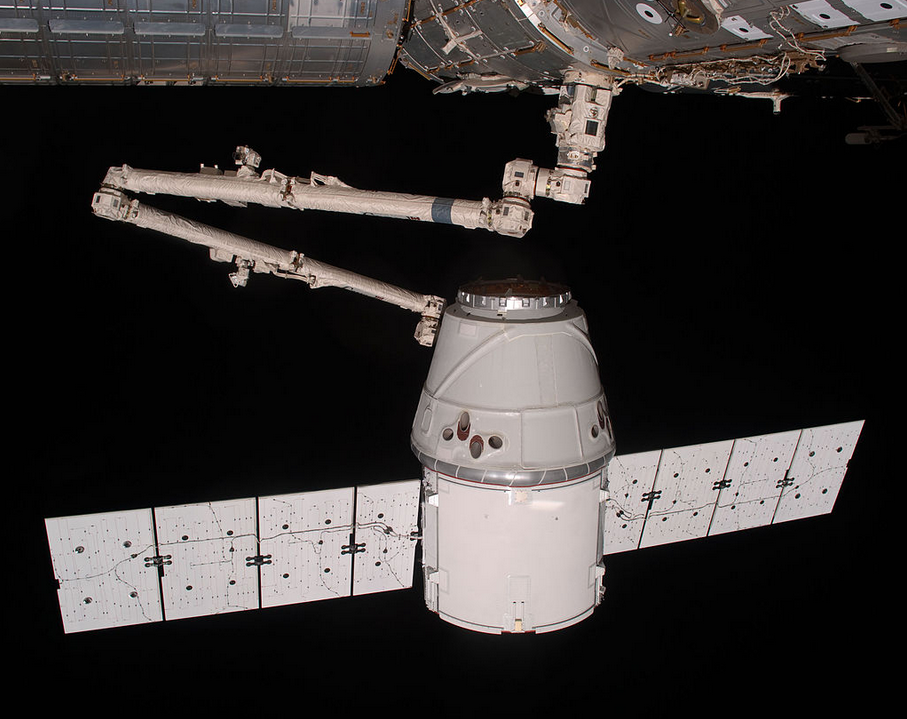

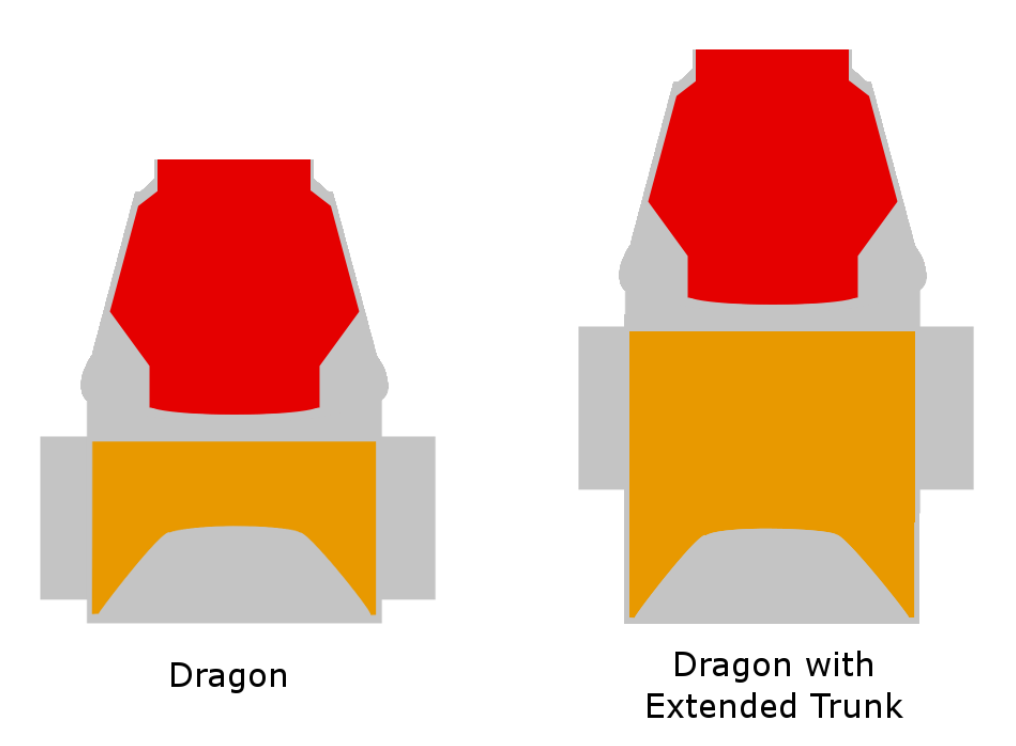

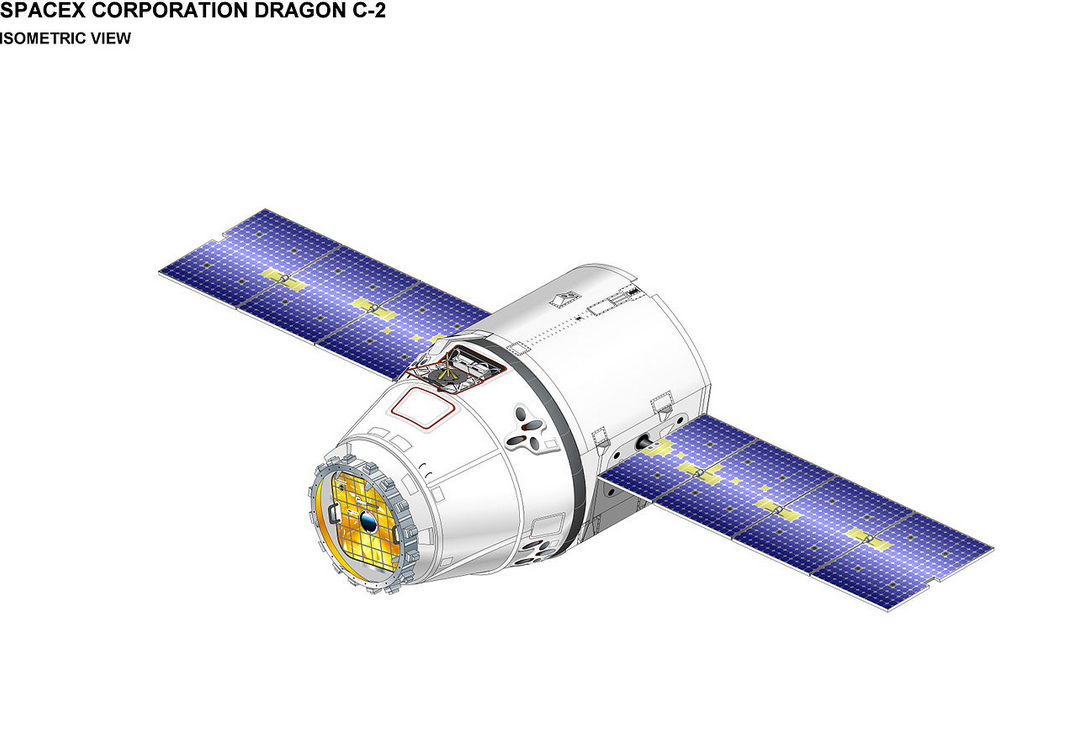

The Dragon spacecraft consists of a nose-cone cap, a conventional blunt-cone ballistic capsule, and an unpressurized cargo-carrier trunk equipped with two solar arrays.[53] The capsule uses a PICA-X heat shield, based on a proprietary variant of NASA's Phenolic impregnated carbon ablator (PICA) material, designed to protect the capsule during Earth atmospheric entry, even at high return velocities from Lunar and Martian missions.[54][55][56] The Dragon capsule is re-usable, and can fly multiple missions.[53] The trunk is not recoverable; it separates from the capsule before re-entry and burns up in Earth's atmosphere.[57] The trunk section, which carries the spacecraft's solar panels and allows the transport of unpressurized cargo to the ISS, was first used for cargo on the SpaceX CRS-2 mission.

The spacecraft is launched atop a Falcon 9 booster.[58] The Dragon capsule is equipped with 16 Draco thrusters.[55] During its initial cargo and crew flights, the Dragon capsule will land in the Pacific Ocean and be returned to the shore by ship.[59]

For the ISS Dragon cargo flights, the ISS's Canadarm2 grapples its Flight-Releasable Grapple Fixture and berths Dragon to the station's US Orbital Segment using a Common Berthing Mechanism (CBM).[60] The CRS Dragon does not have an independent means of maintaining a breathable atmosphere for astronauts and instead circulates in fresh air from the ISS.[61] For typical missions, Dragon is planned to remain berthed to the ISS for about 30 days.[62]

The Dragon capsule can transport 3,310 kilograms (7,300 lb) of cargo, which can be all pressurized, all unpressurized, or a combination thereof. It can return to Earth 3,310 kilograms (7,300 lb), which can be all unpressurized disposal mass, or up to 3,310 kilograms (7,300 lb) of return pressurized cargo, driven by parachute limitations. There is a volume constraint of 14 cubic metres (490 cu ft) trunk unpressurized cargo and 11.2 cubic metres (400 cu ft) of pressurized cargo (up or down).[63] The trunk was first used operationally on the Dragon's CRS-2 mission in March 2013.[64] Its solar arrays produce a peak power of 4 kW.[65]

The design was modified beginning with the fifth Dragon flight on the SpaceX CRS-3 mission to the ISS in March 2014. While the outer mold line of the Dragon was unchanged, the avionics and cargo racks were redesigned to supply substantially more electrical power to powered cargo devices, including the GLACIER freezer module and MERLIN freezer module freezer modules for transporting critical science payloads.[66]

6. Variants and Derivatives

6.1. DragonLab

SpaceX planned to fly the Dragon spacecraft in a free-flying configuration, known as DragonLab.[53] Its subsystems include propulsion, power, thermal and environmental control (ECLSS), avionics, communications, thermal protection, flight software, guidance and navigation systems, and entry, descent, landing, and recovery gear.[67] It has a total combined upmass of 6,000 kilograms (13,000 lb) upon launch, and a maximum downmass of 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb) when returning to Earth.[67] In November 2014, there were two DragonLab missions listed on the SpaceX launch manifest: one in 2016 and another in 2018.[68] However, these missions were removed from the manifest in early 2017, with no official SpaceX statement.[69] The American Biosatellites once performed similar uncrewed payload-delivery functions, and the Russian Bion satellites still continue to do so.

6.2. Dragon 2: Crew and Cargo

A successor of Dragon called SpaceX Dragon 2 has been developed by SpaceX, designed to carry passengers and crew. It has been designed to be able to carry up to seven astronauts, or some mix of crew and cargo, to and from low Earth orbit.[70] The Dragon 2 heat shield is designed to withstand Earth re-entry velocities from Lunar and Martian spaceflights.[54] SpaceX undertook several U.S. Government contracts to develop the Dragon 2 crewed variant, including a Commercial Crew Development 2 (CCDev 2) - funded Space Act Agreement in April 2011, and a Commercial Crew integrated Capability (CCiCap) - funded space act agreement in August 2014.[71] The phase 2 of the CRS contract uses the Dragon 2 Cargo variant lacking cockpit controls, seats and life support systems.[72]

6.3. Red Dragon

Red Dragon was a cancelled version of the Dragon spacecraft that had been previously proposed to fly farther than Earth orbit and transit to Mars via interplanetary space. In addition to SpaceX's own privately funded plans for an eventual Mars mission, NASA Ames Research Center had developed a concept called Red Dragon: a low-cost Mars mission that would use Falcon Heavy as the launch vehicle and trans-Martian injection vehicle, and the SpaceX Dragon 2-based capsule to enter the atmosphere of Mars. The concept was originally envisioned for launch in 2018 as a NASA Discovery mission, then alternatively for 2022, but was never formally submitted for funding within NASA.[73] The mission would have been designed to return samples from Mars to Earth at a fraction of the cost of NASA's own sample-return mission, which was projected in 2015 to cost US$6 billion.[73]

On 27 April 2016, SpaceX announced its plan to go ahead and launch a modified Dragon lander to Mars in 2018.[74][75] However, Musk canceled the Red Dragon program in July 2017 to focus on developing the Starship system instead.[76][77] The modified Red Dragon capsule would have performed all entry, descent and landing (EDL) functions needed to deliver payloads of 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) or more to the Martian surface without using a parachute. Preliminary analysis showed that the capsule's atmospheric drag would slow it enough for the final stage of its descent to be within the abilities of its SuperDraco retro-propulsion thrusters.[78][79]

6.4. Dragon XL

On 27 March 2020, SpaceX revealed the Dragon XL resupply spacecraft to carry pressurized and unpressurized cargo, experiments and other supplies to NASA's planned Lunar Gateway under a Gateway Logistics Services (GLS) contract.[80][81] The equipment delivered by Dragon XL missions could include sample collection materials, spacesuits and other items astronauts may need on the Gateway and on the surface of the Moon, according to NASA. It will launch on SpaceX Falcon Heavy rockets from LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The Dragon XL will stay at the Gateway for 6 to 12 months at a time, when research payloads inside and outside the cargo vessel could be operated remotely, even when crews are not present.[82] Its payload capacity is expected to be more than 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb) to lunar orbit.[83] There is no requirement for a return to Earth. At the end of the mission the Dragon XL must be able to undock and dispose of the same mass it can bring to the Gateway, by moving the spacecraft to a heliocentric orbit.[84]

7. List of Vehicles

| Serial | Name | Type | Status | Flights | Time in flight | Notes | Cat. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C101 | N/A | Prototype | Retired | 1 | 3h, 19m | On display at SpaceX's headquarters. | |

| C102 | N/A | Production | Retired | 1 | 9d, 7h, 57m | On display at Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex. | |

| C103 | N/A | Production | Retired | 1 | 20d, 18h, 47m | . | |

| C104 | N/A | Production | Retired | 1 | 25d, 1h, 24m | . | |

| C105 | N/A | Production | Retired | 1 | 29d, 23h, 38m | . | |

| C106 | N/A | Production | Retired | 3 | 97d, 3h, 2m | . | |

| C107 | N/A | Production | Retired | 1 | 31d, 14h, 56m | Used for CRS-5. | |

| C108 | N/A | Production | Retired | 3 | 98d, 18h, 50m | . | |

| C109 | N/A | Production | Destroyed | 1 | 2m, 19s | Destroyed upon impact with the ocean after the in-flight explosion of the Falcon 9 first stage during CRS-7. | |

| C110 | N/A | Production | Retired | 2 | 65d, 20h, 20m | . | |

| C111 | N/A | Production | Retired | 2 | 74d, 23h, 38m | . | |

| C112 | N/A | Production | Retired | 3 | 99d, 1h | . | |

| C113 | N/A | Production | Retired | 2 | 64d, 12h, 4m | Final Dragon 1 capsule produced. Used twice for CRS-12 and CRS-17. |

8. List of Missions

Launch dates are listed in UTC.

| Mission | Patch | Capsule No.[85] | Launch date (UTC) | Remarks | Time at ISS (dd:hh:mm) |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpX-C1 | SpX-C1 Patch | C101[86] | 8 December 2010 [87] | First Dragon mission, second Falcon 9 launch. Mission tested the orbital maneuvering and reentry of the Dragon capsule. After recovery, the capsule was put on display at SpaceX's headquarters.[86] | N/A | Success |

| SpX-C2+ | SpX-C2+ Patch | C102 | 22 May 2012 [22] | 5d 17h 47m | Success [29] | |

| CRS-1 |  |

C103 | 8 October 2012 [88] | First Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) mission for NASA, first non-demo mission. Falcon 9 rocket suffered a partial engine failure during launch but was able to deliver Dragon into orbit.[34] However, a secondary payload did not reach its correct orbit.[89][90][91] | 17d 22h 16m | Success; launch anomaly [35] |

| CRS-2 |  |

C104 | 1 March 2013 [92][93] | First launch of Dragon using trunk section to carry cargo.[64] Launch was successful, but anomalies occurred with the spacecraft's thrusters shortly after liftoff. Thruster function was later restored and orbit corrections were made,[92] but the spacecraft's rendezvous with the ISS was delayed from its planned date of 2 March until 3 March 2013, when it was successfully berthed with the Harmony module.[94][95] Dragon splashed down safely in the Pacific Ocean on 26 March 2013.[96] | 22d 18h 14m | Success; spacecraft anomaly[92] |

| CRS-3 |  |

C105 | 18 April 2014 [97][98] | First launch of the redesigned Dragon: same outer mold line with the avionics and cargo racks redesigned to supply substantially more electric power to powered cargo devices, including additional cargo freezers (GLACIER freezer module (GLACIER), Minus Eighty Degree Laboratory Freezer for ISS (MERLIN)) for transporting critical science payloads.[66] Launch rescheduled for 18 April 2014 due to a helium leak. | 27d 21h 49m | Success [99] |

| CRS-4 |  |

C106[100] | 21 September 2014 [101] | First launch of a Dragon with living payload, in the form of 20 mice which are part of a NASA experiment to study the physiological effects of long-duration spaceflight.[102] | 31d 22h 41m | Success [103] |

| CRS-5 |  |

C107 | 10 January 2015 [101] | Cargo manifest change due to Cygnus CRS Orb-3 launch failure.[104] Carried the Cloud Aerosol Transport System experiment. | 29d 3h 17m | Success |

| CRS-6 |  |

C108[100] | 14 April 2015 | The robotic SpaceX Dragon capsule splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on 21 May 2015. | 33d 20h | Success |

| CRS-7 |  |

C109 | 28 June 2015 [105] | This mission was supposed to deliver the first of two International Docking Adapters (IDA) to modify Russian APAS-95 docking ports to the newer international standard. The payload was lost due to an in-flight explosion of the carrier rocket. The Dragon capsule survived the blast; it could have deployed its parachutes and performed a splashdown in the ocean, but its software did not take this situation into account.[106] | N/A | Failure |

| CRS-8 |  |

C110 | 8 April 2016 [107] | Delivered the Bigelow Aerospace Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) module in the unpressurized cargo trunk.[108] First stage landed for the first time successfully on sea barge. A month later, the Dragon capsule was recovered, carrying a downmass containing astronaut's Scott Kelly biological samples from his year-long mission on board of ISS.[109] | 30d 21h 3m | Success [110] |

| CRS-9 |  |

C111 | 18 July 2016 [111] | Delivered docking adapter International Docking Adapter (IDA-2) to modify the ISS docking port Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA-2) for Commercial Crew spacecraft.

Longest time a Dragon Capsule was in space. |

36d 6h 57m | Success |

| CRS-10 |  |

C112 | 19 February 2017 [112] | First launch from Kennedy Space Center LC-39A since STS-135 in mid-2011. Berthing to the ISS was delayed by a day due to software incompatibilities.[113] | 23d 8h 8m | Success [114] |

| CRS-11 |  |

C106.2 ♺ [100] | 3 June 2017 | The first mission to re-fly a recovered Dragon capsule (previously flown on SpaceX CRS-4). | 27d 1h 53m | Success [115] |

| CRS-12 |  |

C113 | 14 August 2017 | Last mission to use a new Dragon 1 spacecraft. | 31d 6h | Success |

| CRS-13 |  |

C108.2 ♺[100] | 15 December 2017 [116] | Second reuse of Dragon capsule. First NASA mission to fly aboard reused Falcon 9.[116] First reuse of this specific Dragon spacecraft. | 25d 21h 21m | Success |

| CRS-14 |  |

C110.2 ♺ | 2 April 2018 | Third reuse of a Dragon capsule, only necessitated replacing its heatshield, trunk, and parachutes.[117] Returned over 4000 pounds of cargo.[118] First reuse of this specific Dragon spacecraft. | 30d 16h | Success |

| CRS-15 |  |

C111.2 ♺[119] | 29 June 2018 [120] | Fourth reuse. First reuse of this specific Dragon spacecraft. | 32d 45m | Success [121] |

| CRS-16 |  |

C112.2 ♺[122] | 5 December 2018 [123] | Fifth reuse. First reuse of this specific Dragon spacecraft. The first-stage booster landing failed due to a grid fin hydraulic pump stall on reentry.[123] | 36d 4h | Success [124] |

| CRS-17 |  |

C113.2 ♺[125] | 4 May 2019 [125] | Sixth reuse. First reuse of this specific Dragon spacecraft. | 27d 23h 2m | Success [126] |

| CRS-18 |  |

C108.3 ♺[127] | 24 July 2019 [128] | Seventh reuse. First capsule to make a third flight. | 30d 20h 24m | Success |

| CRS-19 | C106.3 ♺[129] | 5 December 2019 [130] | Eighth reuse. Second capsule to make a third flight. | 29d 19h 54m | Success | |

| CRS-20 |  |

C112.3 ♺[131] | 7 March 2020 [132] | Ninth reuse. Third capsule to make a third flight. Final launch of this Dragon version (Dragon 1), with following launches using SpaceX Dragon 2.[133] |

28d 22h 12m | Success |

9. Specifications

9.1. DragonLab

The following specifications are published by SpaceX for the non-NASA, non-ISS commercial flights of the refurbished Dragon capsules, listed as "DragonLab" flights on the SpaceX manifest. The specifications for the NASA-contracted Dragon Cargo were not included in the 2009 DragonLab datasheet.[67]

Pressure Vessel

- 10 cubic metres (350 cu ft) interior pressurized, environmentally controlled, payload volume.[67]

- Onboard environment: 10–46 °C (50–115 °F); relative humidity 25~75%; 13.9~14.9 psia air pressure (958.4~1027 hPa).[67]

Unpressurized Sensor Bay (Recoverable Payload)

- 0.1 cubic metres (3.5 cu ft) unpressurized payload volume.

- Sensor bay hatch opens after orbit insertion to allow full sensor access to the outer space environment, and closes before Earth atmosphere re-entry.[67]

Unpressurized Trunk (Non-Recoverable)

- 14 cubic metres (490 cu ft) payload volume in the 2.3 metres (7 ft 7 in) trunk, aft of the pressure vessel heat shield, with optional trunk extension to 4.3 metres (14 ft) total length, payload volume increases to 34 cubic metres (1,200 cu ft).[67]

- Supports sensors and space apertures up to 3.5 metres (11 ft) in diameter.[67]

Power, Communication and Command Systems

- Power: twin solar panels providing 1500 watts average, 4000 watts peak, at 28 and 120 VDC.[67]

- Spacecraft communication: commercial standard RS-422 and military standard 1553 serial I/O, plus Ethernet communications for IP-addressable standard payload service.

- Command uplink: 300 kbit/s.[67]

- Telemetry/data downlink: 300 Mbit/s standard, fault-tolerant S-band telemetry and video transmitters.[67]

9.2. Radiation Tolerance

Including the flight computers, Dragon employs 18 triply-redundant processing units, for a total of 54 processors.[13]

References

- "5 Fun Facts About Private Rocket Company SpaceX". Space.com. 21 May 2012. http://www.space.com/15799-spacex-dragon-capsule-fun-facts.html.

- Berger, Brian (8 March 2006). "SpaceX building reusable crew capsule". NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/11699810.

- "NASA selects crew, cargo launch partners". Spaceflight Now. 18 August 2006. http://www.spaceflightnow.com/news/n0608/18cots/.

- error

- Bergin, Chris (19 February 2008). "Orbital beat a dozen competitors to win NASA COTS contract". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2008/02/orbital-beat-a-dozen-competitors-to-win-nasa-cots-contract/.

- "F9/Dragon Will Replace the Cargo Transport Function of the Space Shuttle after 2010" (Press release). SpaceX. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090721083827/http://www.spacex.com/press.php?page=20081223

- "SpaceX Manufactured Heat Shield Material Passes High Temperature Tests Simulating Reentry Heating Conditions of Dragon Spacecraft" (Press release). SpaceX. 23 February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2009.(original link is dead; see version at businesswire (accessed 1 September 2015) http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20090223005140/en/SpaceX-Manufactured-Heat-Shield-Material-Passes-High

- Chaikin, Andrew (January 2012). "1 visionary + 3 launchers + 1,500 employees = ? : Is SpaceX changing the rocket equation?". Air and Space Smithsonian. http://www.airspacemag.com/space-exploration/Visionary-Launchers-Employees.html?c=y&page=2.

- "UPDATE: Wednesday, 23 September 2009" (Press release). SpaceX. 23 September 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20120419063103/http://www.spacex.com/updates_archive.php?page=2009_2

- Update: 23 September 2009 . SpaceX.com. Retrieved 9 November 2012. http://www.spacex.com/updates.php

- Bergin, Chris (28 March 2010). "SpaceX announce successful activation of Dragon's CUCU onboard ISS". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2010/03/spacex-activation-dragons-cucu-onboard-iss/.

- "Former astronaut Bowersox Joins SpaceX as vice president of Astronaut Safety and Mission Assurance" (Press release). SpaceX. 18 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120118115539/http://www.spacex.com/press.php?page=20090618

- error

- Bergin, Chris (3 March 2015). "NASA lines up four additional CRS missions for Dragon and Cygnus". NASA SpaceFlight. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/03/nasa-crs-missions-dragon-cygnus/.

- de Selding, Peter B. (24 February 2016). "SpaceX wins 5 new space station cargo missions in NASA contract estimated at US$700 million". Space News. http://spacenews.com/spacex-wins-5-new-space-station-cargo-missions-in-nasa-contract-estimated-at-700-million/.

- "Sierra Nevada Corp. joins SpaceX and Orbital ATK in winning NASA resupply contracts". The Washington Post. 14 January 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2016/01/14/nasa-expected-to-soon-announce-contracts-to-resupply-the-international-space-station/.

- Guy Norris (20 September 2009). "SpaceX, Orbital Explore Using Their Launch Vehicles To Carry Humans". Aviation Week. http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story.jsp?id=news/COTS09209.xml&channel=awst.

- "SpaceX Achieves Orbital Bullseye With Inaugural Flight of Falcon 9 Rocket: A major win for NASA's plan to use commercial rockets for astronaut transport". SpaceX. 7 June 2010. http://www.spacex.com/press.php?page=20100607.

- "Private space capsule's maiden voyage ends with a splash". BBC News. 8 December 2010. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11948329.

- "STS-133: SpaceX's DragonEye set for late installation on Discovery". NASASpaceflight.com. 19 July 2010. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2010/07/sts-133-spacexs-dragoneye-late-installation-discovery/.

- "NASA Statements on FAA Granting Reentry License To SpaceX" (Press release). 22 November 2010. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2010/nov/10-298_NASA_Statements.html

- "SpaceX Launches Private Capsule on Historic Trip to Space Station". Space.com. 22 May 2012. http://www.space.com/15805-spacex-private-capsule-launches-space-station.html.

- Ray, Justin (9 December 2011). "SpaceX demo flights merged as launch date targeted". Spaceflight Now. http://www.spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/003/111209dates/.

- "SpaceX's Dragon captured by ISS, preparing for historic berthing". NASASpaceflight.com. 25 May 2012. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/05/spacexs-dragon-historic-attempt-berth-with-iss/.

- "ISS welcomes SpaceX Dragon" Wired 25 May 2012 Retrieved 13 September 2012 https://www.wired.com/autopia/2012/05/spacex-docking/

- "SpaceX's Dragon already achieving key milestones following Falcon 9 ride". NASASpaceflight.com. 22 May 2012. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/05/spacexs-dragon-achieving-milestones-falcon-9-ride/.

- "NASA ISS On-Orbit Status 22 May 2012". NASA via SpaceRef.com. 22 May 2012. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=40906.

- Pierrot Durand (28 May 2012). "Cargo Aboard Dragon Spacecraft to Be Unloaded On May 28". French Tribune. http://frenchtribune.com/teneur/1211418-cargo-aboard-dragon-spacecraft-be-unloaded-may-28.

- "Splashdown for SpaceX Dragon spacecraft". BBC. 31 May 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-18273811.

- "SpaceX Dragon Capsule opens new era". Reuters via BusinessTech.co.za. 28 May 2012. http://businesstech.co.za/news/general/13755/spacex-dragon-capsule-opens-new-era/.

- "NASA Administrator Announces New Commercial Crew And Cargo Milestones" NASA 23 August 2012 Retrieved 4 September 2012 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. http://www.nasa.gov/exploration/commercial/crew-cargo-milestones.html

- "SpaceX Dragon specs". http://www.spacex.com/dragon.

- "SpaceX CRS-12 mission comes to a close with Dragon's splashdown". SpaceFlight Insider. 18 September 2017. https://www.spaceflightinsider.com/organizations/space-exploration-technologies/spacex-crs-12-mission-comes-close-dragon-splashdown/.

- "Liftoff! SpaceX Dragon Launches 1st Private Space Station Cargo Mission". Space.com. 8 October 2012. http://www.space.com/17943-spacex-dragon-capsule-space-cargo-launch.html.

- "SpaceX capsule returns with safe landing in Pacific Ocean". BBC. 28 October 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-20118963.

- Clark, Stephen. "Cargo manifest for SpaceX's 11th resupply mission to the space station". Spaceflight Now. https://spaceflightnow.com/2017/06/03/cargo-manifest-for-spacexs-11th-resupply-mission-to-the-space-station/.

- "The Neutron star Interior Composition ExploreR Mission". NASA. https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/nicer/. "Previously scheduled for a December 2016 launch on SpaceX-12, NICER will now fly to the International Space Station with two other payloads on SpaceX Commercial Resupply Services (CRS)-11, in the Dragon vehicle's unpressurized Trunk."

- Foust, Jeff (14 October 2016). "SpaceX to reuse Dragon capsules on cargo missions". SpaceNews. http://spacenews.com/spacex-to-reuse-dragon-capsules-on-cargo-missions/.

- Gebhardt, Chris (28 May 2017). "SpaceX static fires CRS-11 Falcon 9 Sunday ahead of ISS mission". NASASpaceFlight.com. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2017/05/spacex-static-fire-crs-11-falcon-9/.

- "SpaceX's CRS-11 Dragon captured by Station for a second time". NASASpaceFlight.com. 5 June 2017. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2017/06/spacexs-crs-11-dragon-station-arrival/.

- Gebhardt, Chris (26 July 2017). "TDRS-M given priority over CRS-12 Dragon as launch dates realign". NASASpaceFlight. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2017/07/tdrs-priority-crs-12-dragon-launch-dates-realign/.

- Bergin, Chris; Gebhardt, Chris (13 January 2018). "SpaceX's CRS-13 Dragon returns home". NASASpaceFlight.com. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2018/01/spacexs-crs-13-dragon-home/.

- "SpaceX – Commercial Crew Development (CCDEV)" (video). 19 June 2015. 3:48. http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2ulp6g.

- "NASA expects a gap in commercial crew funding" Spaceflightnow.com 11 October 2010 Retrieved 28 February 2011 http://spaceflightnow.com/news/n1010/11commercialcrew/

- "This Week in Space interview with Elon Musk". Spaceflight Now. 24 January 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifwFa5DtIps.

- "Elon Musk's SpaceX presentation to the Augustine panel". YouTube. June 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O81Zq02eStg.

- Rosenberg, Zach (30 March 2012). "Boeing details bid to win NASA shuttle replacement". FlightGlobal. http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/boeing-details-bid-to-win-nasa-shuttle-replacement-370213/.

- "Commercial Crew Integrated Capability". NASA. 23 January 2012. https://www.fbo.gov/index?s=opportunity&mode=form&id=230715a3035c3af460f542da1ad80562&tab=core&_cview=0. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Shotwell, Gwynne (4 June 2014). Discussion with Gwynne Shotwell, President and COO, SpaceX. Atlantic Council. Event occurs at 12:20–13:10. Archived from the original on 2014-06-05. Retrieved 8 June 2014. NASA ultimately gave us about $396 million; SpaceX put in over $450 million ... [for an] EELV-class launch vehicle ... as well as a capsule https://web.archive.org/web/20140605154442/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYocHwhfFDc&gl=US&hl=en

- Chow, Denise (8 December 2010). "Q & A with SpaceX CEO Elon Musk: Master of Private Space Dragons". Space.com. http://www.space.com/10443-spacex-ceo-elon-musk-master-private-space-dragons.html.

- "Fibersim helps SpaceX manufacture composite parts for Dragon spacecraft". ReinforcedPlastics.com. 15 June 2012. http://www.reinforcedplastics.com/view/26038/fibersim-helps-spacex-manufacture-composite-parts-for-dragon-spacecraft/.

- "Production at SpaceX". SpaceX. 24 September 2013. http://www.spacex.com/news/2013/09/24/production-spacex.

- "Dragon Overview". SpaceX. http://www.spacex.com/dragon.php.

- Clark, Stephen (16 July 2010). "Second Falcon 9 rocket begins arriving at the Cape". Spaceflight Now. http://www.spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/002/100716firststage/.

- "SpaceX Updates". SpaceX. 10 December 2007. http://www.spacex.com/updates_archive.php.

- "Second Falcon 9 rocket begins arriving at the Cape". Spaceflight Now. 16 July 2010. http://spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/002/100716firststage/.

- "SpaceX CRS-2 Dragon return timeline". Spaceflight Now. 26 March 2013. http://spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/005/returntimeline.html. "The unpressurized trunk section of the Dragon spacecraft separates. The trunk is designed to burn up on re-entry, while the pressurized capsule returns to Earth intact."

- Jones, Thomas D. (December 2006). "Tech Watch — Resident Astronaut". Popular Mechanics 183 (12): 31. ISSN 0032-4558. http://www.worldcat.org/issn/0032-4558

- "SpaceX • COTS Flight 1 Press Kit". SpaceX. 6 December 2010. http://www.spacex.com/downloads/cots1-20101206.pdf.

- Bergin, Chris (12 April 2012). "ISS translates robotic assets in preparation to greet SpaceX's Dragon". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/04/iss-robotic-arm-preparation-greet-spacexs-dragon/.

- "SpaceX Dragon Air Circulation System". SpaceX / American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. 2011. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20110014250_2011013540.pdf. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "NASA Advisory Council Space Operations Committee". NASA. July 2010. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/483771main_Space_Ops_Committee_Report_July_2010.pdf. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "The ISS CRS contract (signed 23 December 2008)" This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/johnson/pdf/418857main_sec_nnj09ga04b.pdf

- Bergin, Chris (19 October 2012). "Dragon enjoying ISS stay, despite minor issues – Falcon 9 investigation begins". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/10/dragon-iss-stay-minor-issues-falcon-9-investigation/. "CRS-2 will debut the use of Dragon's trunk section, capable of delivering unpressurized cargo, prior to the payload being removed by the ISS' robotic assets after berthing."

- "The Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2012". Federal Aviation Administration. February 2012. http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/media/The_Annual_Compendium_of_Commercial_Space_Transporation_2012.pdf.

- Gwynne Shotwell (21 March 2014). Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell (audio file). The Space Show. Event occurs at 18:35–19:10. 2212. Archived from the original (mp3) on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014. looks the same on the outside... new avionics system, new software, and new cargo racking system http://www.thespaceshow.com/detail.asp?q=2212

- "DragonLab datasheet". SpaceX. 8 September 2009. http://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/files/pdf/DragonLabFactSheet.pdf.

- "Launch Manifest". SpaceX. 2011. http://www.spacex.com/launch_manifest.php.

- "Launch Manifest". SpaceX. 11 December 2014. http://www.spacex.com/launch_manifest.php.

- "Space Exploration Technologies Corporation". 2012-05-03. http://www.spacex.com/press.php?page=20111020.

- Bergin, Chris (16 September 2014). "Dream Chaser misses out on CCtCAP – Dragon and CST-100 win through". NASA SpaceFlight. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2014/09/dream-chaser-misses-out-cctcap-dragon-cst-100-win/.

- Clark, Stephen (2019-08-02). "SpaceX to begin flights under new cargo resupply contract next year". https://spaceflightnow.com/2019/08/02/spacex-to-begin-flights-under-new-cargo-resupply-contract-next-year/.

- Wall, Mike (10 September 2015). ""Red Dragon" Mars Sample-Return Mission Could Launch by 2022". Space.com. http://www.space.com/30504-spacex-red-dragon-mars-sample-return.html.

- @SpaceX (27 April 2016). "Planning to send Dragon to Mars as soon as 2018. Red Dragons will inform overall Mars architecture, details to come". https://twitter.com/SpaceX/status/725351354537906176.

- Newmann, Dava. "Exploring Together". http://blogs.nasa.gov/newman/2016/04/27/exploring-together/. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Berger, Eric (19 July 2017). "SpaceX appears to have pulled the plug on its Red Dragon plans". https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/07/spacex-appears-to-have-pulled-the-plug-on-its-red-dragon-plans/.

- Grush, Loren (19 July 2017). "Elon Musk suggests SpaceX is scrapping its plans to land Dragon capsules on Mars". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2017/7/19/15999384/elon-musk-spacex-dragon-capsule-mars-mission.

- Wall, Mike (31 July 2011). ""Red Dragon" Mission Mulled as Cheap Search for Mars Life". Space.com. http://www.space.com/12489-nasa-mars-life-private-spaceship-red-dragon.html.

- "NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL (NAC) – Science Committee Report". NASA Ames Research Center. 1 November 2011. https://science.nasa.gov/media/medialibrary/2012/01/23/NAC_Science_Meeting_ReportOctober_31-November_1_2011-finalTAGGED.pdf. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Potter, Sean (27 March 2020). "NASA Awards Artemis Contract for Gateway Logistics Services". http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-awards-artemis-contract-for-gateway-logistics-services. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Foust, Jeff (27 March 2020). "SpaceX wins NASA commercial cargo contract for lunar Gateway". https://spacenews.com/spacex-wins-nasa-commercial-cargo-contract-for-lunar-gateway/.

- Clark, Stephen. "NASA picks SpaceX to deliver cargo to Gateway station in lunar orbit". Spaceflight Now. https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/03/27/nasa-picks-spacex-to-deliver-cargo-to-gateway-station-in-lunar-orbit/.

- "Dragon XL revealed as NASA ties SpaceX to Lunar Gateway supply contract". 27 March 2020. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2020/03/dragon-xl-nasa-spacex-lunar-gateway-supply-contract/.

- "NASA delays starting contract with SpaceX for Gateway cargo services". 15 April 2021. https://spacenews.com/nasa-delays-starting-contract-with-spacex-for-gateway-cargo-services/.

- "Dragon C2, CRS-1,... CRS-20 (SpX 1,... 20)". https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/dragon.htm.

- "Dragon C1". https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/dragon-c1.htm.

- "SpaceX Launches Success with Falcon 9/Dragon Flight". NASA. 9 December 2010. http://www.nasa.gov/offices/c3po/home/spacexfeature.html. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Falcon 9 undergoes pad rehearsal for October launch". Spaceflight Now. 31 August 2012. http://spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/004/120831wdr/.

- "Falcon 9 Drops Orbcomm Satellite in Wrong Orbit". Aviation Week. 8 October 2012. http://www.aviationweek.com/Blogs.aspx?plckBlogId=Blog:04ce340e-4b63-4d23-9695-d49ab661f385&plckPostId=Blog%3A04ce340e-4b63-4d23-9695-d49ab661f385Post%3Afdf0d27c-fdf2-4efb-a71f-8272017dbfc3.

- "Worldwide Launch Schedule". Spaceflight Now. 7 September 2012. http://spaceflightnow.com/tracking/.

- "Private Spacecraft to Launch Space Station Cargo on 7 October 2012". LiveScience. 25 September 2012. http://www.livescience.com/23444-spacex-dragon-space-station-cargo-mission.html.

- "Dragon Spacecraft Glitch Was "Frightening", SpaceX Chief Elon Musk Says". Space.com. 1 March 2013. http://www.space.com/20035-spacex-dragon-glitch-elon-musk.html.

- "Dragon Mission Report". Spaceflight Now. http://www.spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/004/121114anomalies/.

- "NASA says SpaceX Dragon is safe to dock with the International Space Station on Sunday". The Verge. 2 March 2013. https://www.theverge.com/2013/3/2/4057394/nasa-clears-spacex-dragon-iss-dock.

- "SpaceX hits snag; Dragon capsule won't dock with space station on schedule". WKMG TV. 1 March 2013. http://www.clickorlando.com/news/SpaceX-hits-snag-Dragon-capsule-won-t-dock-with-space-station-on-schedule/-/1637132/19119852/-/2mcd1p/-/index.html.

- "SpaceX Dragon cargo ship splashes into Pacific". Boston Globe. 26 March 2013. http://www.boston.com/news/science/2013/03/26/spacex-dragon-cargo-ship-splashes-into-pacific/tm355lhjaaPX6zknTiOSNN/story.html.

- "Range Realigns – SpaceX CRS-3 mission targets April 14". NASASpaceflight.com. 4 April 2014. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2014/04/range-realigns-spacex-crs-3-april/.

- "CRS-3 Update". http://new.livestream.com/spacex/events/2833937/statuses/48058415.

- "[SpaceX Launch of SpaceX's Dragon CRS-3 Spacecraft on Falcon 9v1.1 Rocket"]. SpaceVids.tv. 18 April 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65zDaDSvIww.

- "SpaceX's CRS-13 Dragon returns home". 13 January 2018. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2018/01/spacexs-crs-13-dragon-home/.

- "Spaceflight Now Tracking Station". spaceflightnow.com. http://spaceflightnow.com/tracking/index.html.

- "SpaceX Dragon Flying Mice in Space and More for NASA". Space.com. 18 September 2014. http://www.space.com/27172-spacex-space-rats-nasa-science-infographic.html.

- "Space X Dragon capsule returns to Earth – CRS-4 Mission ends with a splash!". http://globalaviationreport.com/2014/10/26/space-x-dragon-capsule-splashes-down-crs-4-mission-ends.

- "Launch of SpaceX's CRS-5 mission slips to 16 December 2014". Spaceflight Insider. 22 November 2014. http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/missions/commercial/launch-spacexs-crs-5-mission-iss-slips-dec-16/.

- "Launch Schedule". http://spaceflightnow.com/launch-schedule/.

- Bergin, Chris (27 July 2015). "Saving Spaceship Dragon – Software to provide contingency chute deploy". NASASpaceFlight.com. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/07/saving-spaceship-dragon-contingency-chute/.

- Cooper, Ben. "Launch Viewing Guide for Cape Canaveral". http://www.launchphotography.com/Delta_4_Atlas_5_Falcon_9_Launch_Viewing.html.

- Lindsey, Clark (16 January 2013). "NASA and Bigelow release details of expandable module for ISS". NewSpace Watch. http://www.newspacewatch.com/articles/nasa-and-bigelow-release-details-of-expandable-module-for-iss.html.

- Clark, Stephen. "Cargo-carrying Dragon spaceship returns to Earth – Spaceflight Now". https://spaceflightnow.com/2016/05/11/cargo-carrying-dragon-spaceship-returns-to-earth/.

- "Dragon Splashdown" (Press release). SpaceX. 11 May 2016. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016. http://www.spacex.com/news/2016/05/11/dragon-splashdown

- "Worldwide Launch Schedule". SpaceflightNow. http://spaceflightnow.com/launch-schedule/.

- Garcia, Mark. "Dragon Launches to Station, Arrives Wednesday". https://blogs.nasa.gov/spacestation/2017/02/19/dragon-launches-to-station-arrives-wednesday/. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Tweet". https://twitter.com/13ericralph31/status/989732014407368704. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- Clark, Stephen. "SpaceX's Dragon supply carrier wraps up 10th mission to space station". Spaceflight Now. https://spaceflightnow.com/2017/03/19/spacexs-dragon-supply-carrier-wraps-up-10th-mission-to-space-station/.

- Etherington, Darrell (3 July 2017). "SpaceX's first re-flown Dragon capsule successfully returns to Earth". Tech Crunch. https://techcrunch.com/2017/07/03/spacexs-first-re-flown-dragon-capsule-successfully-returns-to-earth/.

- Graham, William (14 December 2017). "Flight proven Falcon 9 launches previously flown Dragon to ISS". NASASpaceFlight.com. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2017/12/flight-proven-falcon-9-launch-flown-dragon-iss/.

- Ralph, Eric (2 April 2018). "SpaceX continues water landing test in latest Space Station resupply mission". https://www.teslarati.com/spacex-experimental-water-landing-falcon-9-test/.

- "Dragon Splashes Down in Pacific With NASA Research and Cargo – Space Station". https://blogs.nasa.gov/spacestation/2018/05/05/dragon-splashes-down-in-pacific-with-nasa-research-and-cargo/.

- "Tweet". https://twitter.com/SpaceX/status/1010644009964920832. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- Cooper, Ben (2 April 2018). "Launch Viewing Guide for Cape Canaveral". http://www.launchphotography.com/Delta_4_Atlas_5_Falcon_9_Launch_Viewing.html.

- Clark, Stephen (3 August 2018). "SpaceX cargo capsule comes back to Earth from space station". Spaceflight Now. https://spaceflightnow.com/2018/08/03/spacex-cargo-capsule-comes-back-to-earth-from-space-station/.

- "SpaceX CRS-16 Dragon Resupply Mission". SpaceX. December 2018. https://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/files/crs16_press_kit_12_3.pdf.

- Lewin, Sarah (5 December 2018). "SpaceX Launches Dragon Cargo Ship to Space Station, But Misses Rocket Landing". Space.com. https://www.space.com/42629-spacex-dragon-launch-missed-landing-crs16.html.

- Bergin, Chris (14 January 2019). "CRS-16 Dragon returns to Earth following ISS departure". NASA SpaceflightNow. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2019/01/crs-16-dragon-departs-iss-return-journey/.

- Ralph, Eric (4 May 2019). "SpaceX gives infrared glimpse of Falcon 9 landing after successful Dragon launch". https://www.teslarati.com/spacex-falcon-9-infrared-landing-cargo-dragon/.

- Bergin, Chris (3 June 2019). "CRS-17 Dragon returns home from ISS mission". NASA SpaceflightNow. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2019/06/crs-17-dragon-eom-homecoming/.

- @SpaceX (19 July 2019). "The Dragon spacecraft supporting this mission previously visited the @space_station in April 2015 and December 2017". https://twitter.com/SpaceX/status/1152361282982465536.

- "Launch Schedule". Spaceflight Now. 19 July 2019. https://spaceflightnow.com/launch-schedule/.

- @SpaceX (27 November 2019). "The Dragon spacecraft supporting this mission previously flew in support of our fourth and eleventh commercial resupply missions". https://twitter.com/SpaceX/status/1199463905258590208.

- "Launch Schedule". Spaceflight Now. 5 December 2019. https://spaceflightnow.com/launch-schedule/.

- @SpaceX (1 March 2020). "The Dragon spacecraft supporting this mission previously flew in support of our tenth and sixteenth commercial resupply missions – this will be the third Dragon to fly on three missions". https://twitter.com/SpaceX/status/1234151642863243265.

- "Launch Schedule". Spaceflight Now. https://spaceflightnow.com/launch-schedule/.

- "Falcon 9 launches final first-generation Dragon". 7 March 2020. https://spacenews.com/falcon-9-launches-final-first-generation-dragon/.