Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elisabetta Albi | -- | 2421 | 2022-10-11 04:02:02 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2421 | 2022-10-11 04:29:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Gizzi, G.; Mazzeschi, C.; Delvecchio, E.; Beccari, T.; Albi, E. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 in Pregnancy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/28780 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Gizzi G, Mazzeschi C, Delvecchio E, Beccari T, Albi E. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 in Pregnancy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/28780. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Gizzi, Giulia, Claudia Mazzeschi, Elisa Delvecchio, Tommaso Beccari, Elisabetta Albi. "Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 in Pregnancy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/28780 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Gizzi, G., Mazzeschi, C., Delvecchio, E., Beccari, T., & Albi, E. (2022, October 11). Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 in Pregnancy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/28780

Gizzi, Giulia, et al. "Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 in Pregnancy." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 October, 2022.

Copy Citation

Pregnancy is generally considered a critical period for women. Pregnancy is associated with dramatic changes in metabolism, hormone production, mood, and the immune system.

COVID-19

pregnant women

confinement

anxiety

depression

1. Introduction

Many studies report that different changes are closely linked to each other and depend on circadian rhythms [1]. The hormonal balance is regulated by the brain in the hypothalamus–pituitary axis. The main hormonal actor in pregnancy is progesterone, which allows implantation of the fertilized egg and silences uterine contractions during the pregnancy period [2]. During late pregnancy, a reduction in progesterone contributes to the progression of parturition and the initiation of lactation [2]. Progesterone influences the cellular metabolism [3] and mood symptoms [4]. Moreover, during pregnancy, estradiol is produced by the placenta, inducing various effects on the immune system and the brain [5]. Notably, estradiol in pregnancy is associated with reduced gray matter volume in the left putamen, with a reduction in cognitive performance and an increase in negative affect symptoms [6]. Additionally, during late pregnancy, prolactin production is responsible for the low anxiety levels in lactating women [7], although anxiety can be experienced in women who have difficulty breastfeeding.

In general, hormonal modifications allow the pregnancy to proceed in a good state of physical–psychological balance, and maternal well-being also includes having a positive childbirth experience [8].

2. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 in Pregnancy

2.1. Stressful Conditions

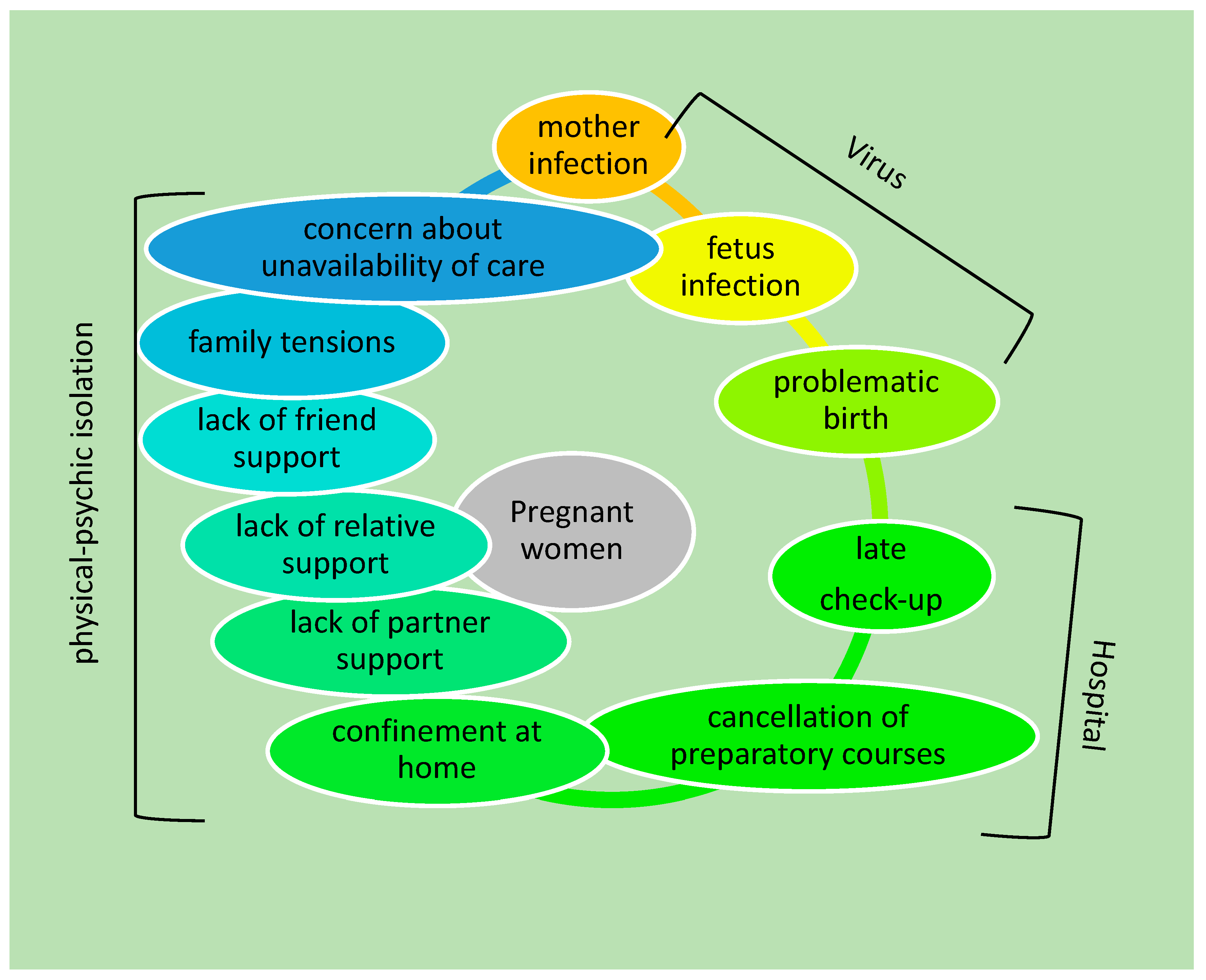

Recent studies have highlighted the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal mental health for stressful conditions linked to (1) virus: the fear of contracting the infection and passing it on to the child, as well as the fear of a problematic birth; (2) hospital: the cancellation of check-ups and pre-birth courses; (3) physical–psychological isolation: confinement accompanied by a lack of family and friend support, increased interpersonal tensions, and concern about the unavailability of care (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the main causes affecting the mental health of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first point had an impact on the mental health of the mothers especially because of they were going through a pregnancy experience or a childbirth experience that did not correspond to their expectations. In fact, in Italy (Udine hospital), a study was conducted on 258 pregnant women with the aim to investigate the reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic by two questions: the first was intended to know if the woman had knowledge about COVID-19, and the second was if the woman knew how to control the possibility of getting infected. Women were aware of COVID-19 and the related problems [9]. In a study conducted in Canada among 1987 pregnant women, the reported symptoms were in part due to concerns with the risk of contracting the virus and its effects on the health of the mother and baby [10]. Similar concerns emerged from a multi-center and cross-sectional study involving 12 provinces of China in which the possibility of contracting the infection and consequently creating problems for oneself and the baby was a prominent concern in many pregnant women [11].

The second point was strictly dependent on the reorganization of the national health system for the pandemic emergency. Part of the hospitals were dedicated to COVID-19 patients, as were doctors and nurses. The consequence was the reduction in follow-up visits and interventions for non-COVID-19 patients. Non-urgent checkups and preparatory courses were canceled for pregnant women to minimize the risk of contagion. Again, pregnant women from different parts of the world were concerned. Italian pregnant women were worried about the cancellation of medical appointments [12]. In March 2020 in Canada, the provinces imposed restrictions with consequent hospital reorganizations. As a result, 4604 English- and French-speaking pregnant Canadians perceived a lack of clinical support [13]. This psychological condition was confirmed by another Canadian study involving 1987 pregnant women who raised concerns about not receiving adequate care [10].

Likewise, in completely different territory, pregnant Chinese women declared a relevant concern if they delayed follow-up visits [11].

The third point opened the door to a general problem concerning all the circumstances in which individuals found themselves in a condition of confinement. Solitary confinement has been found to have a variety of negative effects dependent on the duration and conditions [14]. A Spanish study conducted in Valencia on 97 pregnant women found that confinement inevitably led to a reduction in physical activity and an increase in sedentary lifestyle, with consequent repercussions on the mood of expectant mothers [15]. This condition was aggravated by the difficulty of interpersonal relationships due to confinement, as well as by family tensions due to the change in lifestyle and, again, by the inability of the partner to attend the birth or be with the future mother in the first days after the birth. The difficulty of interpersonal relationships, studied by the Social Support Effectiveness Questionnaire (SSEQ), was highlighted by the Canadian study reported above [10]. The importance in Canada of social support for pregnant women during the pandemic was also shown by Khoury et al. [16].

A condition of suffering due to physical absence and/or the absence of support from one’s partner in the perinatal period was detected in an Italian study conducted on 575 pregnant women [17]. Moreover, 114 pregnant English-speaking American women, residents of Sedgwick County, adopted strategies for self-care, to avoid the risk of contamination, and for a good family organization [18]. The authors reported that a quarter of patients complained of a decrease in support from family, friends, coworkers, and support services. Additionally, negative behaviors attributed to the pandemic were reported, such as a decrease in physical activity and an increase in tobacco and alcohol consumption [18]. In a Chinese study, pregnant women recruited before and after the COVID-19 pandemic were questioned about their families via the Family Environment Scale (FES). From the analysis of the data, reduced family cohesion and an increased level of conflict were highlighted [19].

2.2. Psychological Symptoms

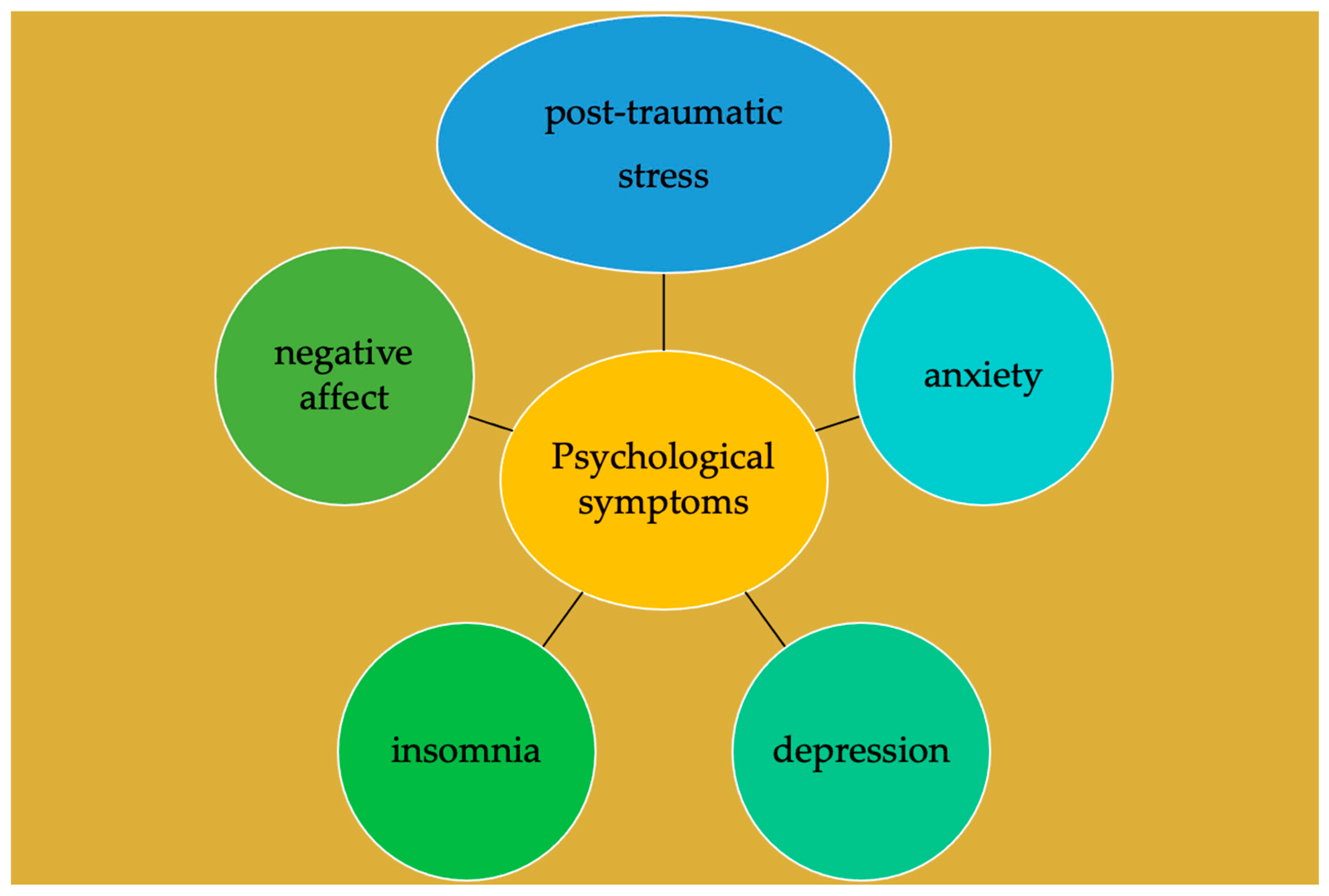

Interestingly, from European and extra-European studies emerged many symptoms triggered by one or more of the above causes (Figure 2). The studies were conducted either by analyzing the symptoms that appeared during the COVID-19 period or by comparing the symptoms between the COVID-19 period and the non-COVID-19 period.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the main mental disorders in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic induced by causes reported in Figure 1.

2.2.1. COVID-19 Period

In order to understand the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of pregnant women, numerous studies have been conducted in different countries around the world. Most of them concern European, American, and Asian countries. The main causes that led to mental disorders were the decrease in the perception of general support, family economic difficulties and the possible state of unemployment, a tendency to disobey the rules of isolation, and a low level of education [20].

European Countries

In Italy, the impaired mental health linked to the COVID-19 pandemic has been demonstrated in several studies. Two of these were carried out at Udine hospital, demonstrating an association between the COVID-19 pandemic and clinical symptoms of anxiety and depression [9][21] and obsessive compulsive disorder [22]. In the first study, 258 pregnant women were analyzed by the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), and an obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) screening [9]. In the second study, 232 pregnant women were analyzed by the Italian version of the Pandemic-Related Pregnancy Stress Scale (PREPS), the Revised Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (NuPDQ), the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) [21].

The high level of depressive symptoms was confirmed by an online anonymous survey prepared by the University of Roma (Central Italy) administered for 6–8 weeks to 286 women who had given birth during the COVID-19 pandemic [22]. The results showed that 64 women had SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and consequently were separated from the newborn, with low probability of breastfeeding. The Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale showed that postnatal depression was relatively common in the whole cohort, but the likelihood of being affected by this mental disorder was higher in women with COVID-19 [22]. The fact that the COVID-19 period was demanding and stressful for pregnant women, with a significant impact on their well-being, was confirmed by another online study. It was organized by the University of Milan and performed with 575 pregnant Italian women by the administration of self-assessment questionnaires concerning the presence of anxiety disorders, depressive symptoms, and post-traumatic stress disorder [17]. The possibility that anxiety in pregnant women during the COVID-19 period could negatively affect prenatal attachment was demonstrated with an online study conducted by a group of researchers from the University of Cosenza (Southern Italy) with self-assessment questionnaires aimed at analyzing socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics, psychological distress (form STAI Y-1-2 and BDI-II), and prenatal attachment (PAI) [23].

In other European countries, the effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of pregnant women were not very different from those found in Italy.

In Spain, it was demonstrated by the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90-R) that for 131 pregnant women, stress and insomnia were predictive variables of anxiety and depressive symptoms related to COVID-19 [24]. In France, a relevant state of anxiety/depression during pregnancy in the COVID-19 period was highlighted by a socio-demographic questionnaire, the Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [25]. Moreover, postpartum anxiety and depression were evaluated with the City Birth Trauma Scale, the Interpersonal Emotional Regulation Questionnaire, and the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory [25].

American Countries

The COVID-19 pandemic has also affected the mental health of pregnant women in America. In a Canadian study (North America) performed with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EPDS), it was shown that more than half of pregnant women during the COVID-19 period had clinically relevant depression symptoms, and more than a third had anxiety symptoms [26]. In Colombia (Southern America), a study that involved seven cities indicated the psychological consequences of the pandemic as anxiety, insomnia, and depression in more pregnant women than those who had actually been affected by the virus [27].

Asian Countries

The situation was no different in Asia. Of note, in China, a depressive state that affected more than a quarter of pregnant women during the COVID-19 period was shown by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [11].

2.2.2. COVID-19 Period Versus Non-COVID-19 Period

Several studies have been carried out with the aim of comparing the mental conditions of pregnant women during the COVID-19 period compared to the non-COVID-19 period.

Differences in Countries

It is known that stressful conditions can be encountered in women during pregnancy for different causes, such as ethnicity, socio-economic status, marital status, employment activity, and cultural level, as well as relationships with parents, partners, and friends [23], with consequences on the health of the child. In fact, it has been reported that stressful maternal conditions can induce the possible onset of emotional problems, cognitive disorders, attention deficit, and hyperactivity in the child [28]. Prenatal stress was particularly high in twin pregnancies. This involved approximately 44% of women in early pregnancy and 51% in late pregnancy, indicating that the stressful condition increased as pregnancy progressed. In the study, it was demonstrated that the premature rupture of the membranes was attributable to the condition of terminal stress. Interestingly, the stressful condition correlated with the women’s BMI and education level [29]. Therefore, numerous studies have been conducted to highlight the difference in the mental health of pregnant women in the non-COVID-19 period and the COVID-19 period. Certainly, demographic factors influence the mental condition of pregnant women both in the non-COVID-19 period and the COVID-19 period [21][30]. However, problems related to the pandemic such as job difficulties resulting in low income, especially for single women, as well as the loss of relatives made the situation much more difficult for pregnant women during the COVID-19 period [31].

European Countries

In Italy, the link between the high levels of anxiety, depression, and hostility of women in the third trimester of pregnancy and the COVID-19 pandemic was demonstrated with the Profile of Mood States and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support by comparing the results with those of pregnant women in the non-COVID-19 period [32].

American Countries

The differences in mental health in pregnant women during the non-COVID-19 period and the COVID-19 period have also been demonstrated in America. To assess the differences between two groups of Boston women in relation to childbirth stress, maternal bonding, and breastfeeding, 1611 women who gave birth during the pandemic and 640 women who gave birth in the non-COVID-19 period were studied with an anonymous internet survey. The results showed that mothers exposed to COVID-19 were found to have a much more acute stress response with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder related to childbirth and breastfeeding problems with subsequent mother–baby bond problems compared to mothers in the non-COVID-19 period [33]. The differences between the two periods were also revealed with the Cambridge Concern Scale (CWS), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS). Moreover, among 303 pregnant women from Ontario, Canada, more than half of the patients had a high level of depression, more than a third had a high level of worry, and more than a fifth had a high level of insomnia during the COVID-19 period in comparison with the non-COVID-19 period [16]. Additionally, higher levels of anxiety, depression, dissociation, post-traumatic stress disorder, and negative affect symptoms were demonstrated in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the non-COVID-19 period in Quebec, Canada, evaluated with the Kessler Distress Scale (K10), the Post-traumatic Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II), and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [34].

Asian Countries

The comparison of the mental conditions of pregnant women between the COVID-19 period and the non-COVID-19 period was also carried out in Asia. At Wuhan Children’s Hospital of China, the data obtained from the Novel Coronavirus-Pregnancy Cohort (NCP) study that included 531 participants and the Healthy Baby Cohort (HBC) study that included 2352 participants were compared. Women analyzed during the pandemic had a higher level of depression but a lower risk of stress than non-COVID-19 women [35]. The authors commented that the stress reduction could be related to the fact that the women participating in the study did not have to travel to the workplace, reducing work-related stress. An increased level of depression but also of somatization, anxiety, hostility, and sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 period compared to the non-COVID-19 period was demonstrated in a Chinese study conducted at Zhejiang Hospital and Shanghai University using the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL90-R) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaires [18].

In addition to all the symptoms listed above, a case of delirium was found at a Mumbai hospital (India) in a woman in the 30th week of pregnancy affected by COVID-19 with already diagnosed anemia and preeclampsia. A premature birth followed, and the episode occurred again 4 days after delivery. Symptoms subsequently improved and the patient was discharged [36].

References

- Albers, H.E.; Gerall, A.A.; Axelson, J.F. Effect of reproductive state on circadian periodicity in the rat. Physiol. Behav. 1981, 26, 21–25.

- Bhurke, A.S.; Bagchi, I.C.; Bagchi, M.K. Progesterone-Regulated Endometrial Factors Controlling Implantation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 75, 237–245.

- Kalkhoff, R.K. Metabolic effects of progesterone. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982, 142, 735–738.

- Standeven, L.R.; McEvoy, K.O.; Osborne, L.M. Progesterone, reproduction, and psychiatric illness. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 69, 108–126.

- Finch, C.L.; Zhang, A.; Kosikova, M.; Kawano, T.; Pasetti, M.F.; Ye, Z.; Ascher, J.R.; Xie, H. Pregnancy level of estradiol attenuated virus-specific humoral immune response in H5N1-infected female mice despite inducing anti-inflammatory protection. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1146–1156.

- Rehbein, E.; Kogler, L.; Kotikalapudi, R.; Sattler, A.; Krylova, M.; Kagan, K.O.; Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Derntl, B. Pregnancy and brain architecture: Associations with hormones, cognition and affect. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 34, e13066.

- Asher, I.; Kaplan, B.; Modai, I.; Neri, A.; Valevski, A.; Weizman, A. Mood and hormonal changes during late pregnancy and puerperium. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 22, 321–325.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Colli, C.; Penengo, C.; Garzitto, M.; Driul, L.; Sala, A.; Degano, M. Prenatal Stress and Psychiatric Symptoms During Early Phases of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. Int. J. Women’s Health 2021, 13, 653–662.

- Lebel, C.; MacKinnon, A.; Bagshawe, M.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 5–13.

- Bo, H.X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.Y. Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms Among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in China During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychosom. Med. 2021, 83, 345–350.

- Cardwell, M.S. Stress: Pregnancy considerations. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2013, 68, 119–129.

- Glover, V. Maternal depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy and child outcome; what needs to be done. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 28, 25–35.

- Arrigo, B.A.; Bullock, J.L. The psychological effects of solitary confinement on prisoners in supermax units: Reviewing what we know and recommending what should change. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2008, 52, 622–640.

- Biviá-Roig, G.; La Rosa, V.L.; Gómez-Tébar, M.; Serrano-Raya, L.; Amer-Cuenca, J.J.; Caruso, S. Analysis of the impact of the confinement resulting from COVID-19 on the lifestyle and psychological wellbeing of Spanish pregnant women: An Internet-based cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5933.

- Khoury, J.E.; Atkinson, L.; Bennett, T.; Jack, S.M.; Gonzalez, A. COVID-19 and mental health during pregnancy: The importance of cognitive appraisal and social support. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1161–1169.

- Molgora, S.; Accordini, M. Motherhood in the Time of Coronavirus: The Impact of the Pandemic Emergency on Expectant and Postpartum Women’s Psychological Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567155.

- Ahlers-Schmidt, C.R.; Hervey, A.M.; Neil, T.; Kuhlmann, S.; Kuhlmann, Z. Concerns of women regarding pregnancy and childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2578–2582.

- Xie, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Alteration in the psychologic status and family environment of pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 153, 71–75.

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, K.; Huang, M.; Qiu, C. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265021.

- Penengo, C.; Colli, C.; Garzitto, M.; Driul, L.; Sala, A.; Degano, M. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Pandemic-Related Pregnancy Stress Scale (PREPS) and its correlation with anxiety and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 48–53.

- Buonsenso, D.; Malorni, W.; Turriziani Colonna, A.; Morini, S.; Sbarbati, M.; Solipaca, A.; Di Mauro, A.; Carducci, B.; Lanzone, A.; Moscato, U.; et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Pregnant Women. Front. Pediatrics 2022, 10, 790518.

- Craig, F.; Gioia, M.C.; Muggeo, V.; Cajiao, J.; Aloi, A.; Martino, I. Effects of maternal psychological distress and perception of COVID-19 on prenatal attachment in a large sample of Italian pregnant women. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 665–672.

- Romero-Gonzalez, B.; Puertas-Gonzalez, J.A.; Mariño-Narvaez, C.; Peralta-Ramirez, M.I. Confinement variables by COVID-19 predictors of anxious and depressive symptoms in pregnant women. Med. Clínica 2021, 156, 172–176.

- Gonzalez-Garcia, V.; Exertier, M.; Denis, A. Anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and emotion regulation: A longitudinal study of pregnant women having given birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2021, 5, 100225.

- Moyer, C.A.; Compton, S.D.; Kaselitz, E.; Muzik, M. Pregnancy-related anxiety during COVID-19: A nationwide survey of 2740 pregnant women. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2020, 23, 757–765.

- Parra-Saavedra, M.; Villa-Villa, I.; Pérez-Olivo, J.; Guzman-Polania, L.; Galvis-Centurion, P.; Cumplido-Romero, A. Attitudes and collateral psychological effects of COVID-19 in pregnant women in Colombia. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 151, 203–208.

- Groulx, T.; Bagshawe, M.; Giesbrecht, G.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Hetherington, E.; Lebel, C.A. Prenatal care disruptions and associations with maternal mental health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2021, 2, 648428.

- Wang, W.; Wen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Tong, C.; et al. Maternal prenatal stress and its effects on primary pregnancy outcomes in twin pregnancies. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 41, 198–204.

- Onwuzurike, C.; Diouf, K.; Meadows, A.R.; Nour, N.M. Racial and ethnic disparities in severity of COVID-19 disease in pregnancy in the United States. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 151, 293–295.

- Yassin, A.; Al-Mistarehi, A.H.; El-Salem, K.; Karasneh, R.A.; Al-Azzam, S.; Qarqash, A.A.; Khasawneh, A.G.; Anas, M.; Zein Alaabdin, A.M.Z.; Soudah, O. Prevalence Estimates and Risk Factors of Anxiety among Healthcare Workers in Jordan over One Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 24, 2615.

- Smorti, M.; Ponti, L.; Ionio, C.; Gallese, M.; Andreol, A.; Bonassi, L. Becoming a mother during the COVID-19 national lockdown in Italy: Issues linked to the wellbeing of pregnant women. Int. J. Psychol. 2022, 57, 146–152.

- Mayopoulos, G.A.; Ein-Dor, T.; Dishy, G.A.; Nandru, R.; Chan, S.J.; Hanley, L.E.; Kaimal, A.J.; Dekel, S. COVID-19 is associated with traumatic childbirth and subsequent mother-infant bonding problems. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 122–125.

- Berthelot, N.; Lemieux, R.; Garon-Bissonnette, J.; Drouin-Maziade, C.; Martel, E.; Maziade, M. Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstet. Et Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 848–855.

- Mei, H.; Li, N.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhou, A. Depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychosom Res. 2021, 149, 110586.

- Mahajan, N.N.; Gajbhiye, R.K.; Pednekar, R.R.; Pophalkar, M.P.; Kesarwani, S.N.; Bhurke, A.V. Delirium in a pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection in India. Indian J. Psychiatry 2021, 55, 102513.

More

Information

Subjects:

Psychology, Social

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

954

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 Oct 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No