| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roberto Piergentili | + 3196 word(s) | 3196 | 2020-10-26 04:48:14 |

Video Upload Options

Y RNA are a class of small non-coding RNA that are largely conserved. Although their discovery was almost 40 years ago, their function is still under investigation. This is evident in cancer biology, where their role was first studied just a dozen years ago. Since then, only a few contributions were published, mostly scattered across different tumor types and, in some cases, also suffering from methodological limitations. Nonetheless, these sparse data may be used to make some estimations and suggest routes to better understand the role of Y RNA in cancer formation and characterization.

1. Introduction

The discovery of Y RNA goes back to 1981 [1], when Lerner and collaborators isolated them in patients affected by systemic lupus erythematosus using specific autoantibodies; this finding was subsequently confirmed in other autoimmune pathologies. The identified targets in these diseases include the soluble ribonucleoproteins (RNP) RO60 (also known as SSA or TROVE2—TROVE domain family, member 2) [2][3] and SSB (small RNA-binding exonuclease protection factor—also known as La) [4]. RNP are complex molecules that include both proteins and RNAs; in RO60 RNP, the RNA component is represented by Y RNA [1][5] which are small non-coding RNAs (sncRNA) that, like other sncRNA, are transcribed by RNA Polymerase III (Pol III) [5][6]. In humans, four genes (RNY1, RNY3, RNY4, and RNY5) encode for Y RNA; they are clustered on chromosome 7q36.1 [7][8] and their transcripts are named hY1 (112 nucleotides (nt)), hY3 (101 nt), hY4 (93 nt), and hY5 (83 nt), respectively.

The Y RNA family is not limited to the transcripts of the four canonical genes described above; there are other 966 hY RNA pseudogenes (368 for hY1, 442 for hY3, 148 for hY4, and 8 for hY5) scattered on all human chromosomes [9], with at least 878 predicted transcripts. Their distribution is generally proportional to the chromosome length, with the notable exceptions of chromosomes 1, 12, and 17 (excess) and Y (only one pseudogene, possibly because of its peculiar structure and content [10]. Interestingly, no pseudogene sequence is 100% identical to the corresponding hY functional RNA and, notably, although most sequence changes are randomly distributed along Y RNA entire sequence, there is a specific enrichment at specific positions [9], suggesting that these changes are not random, at least in some sequences.

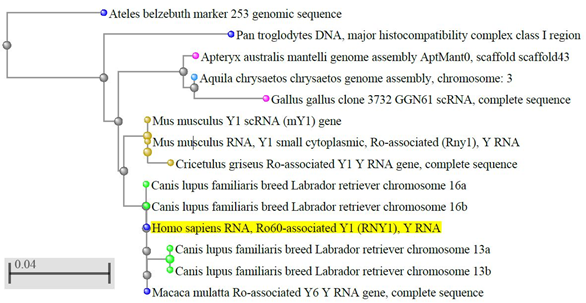

Y RNA are conserved molecules [11][12][13][14][15] (Figure 1) and, in vertebrates, also their clustering is conserved [15][16][17]. A BLAST search shows that the sequence identity is higher than 90% in most vertebrates. Instead, in some non-vertebrate organisms and microorganisms, the sequence similarity with the vertebrate Y RNA is only partial [18] and in plants and fungi they have not been identified yet, thus their evolution is still debated.

Figure 1. Evolutionary conservation of Y RNA in vertebrates. The dendrogram shows the conservation of human hY1 in monkeys, dogs, rodents, and birds; only best matches (identity >95%) were selected. The tree was obtained through the NCBI BLAST website (URL: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on April 2020), using default settings. Out of the 100 results displayed, we selected only those coming from genome sequences, thus excluding predicted sequences, human pseudogenes, bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones, and other constructs. The color codes, set by default by the NCBI website, are as follows: yellow highlight: query sequence; light blue dots: hawks and eagles; pink dots: birds; brown dots: rodents; blue dots: primates; green dots: carnivores; grey dots: nodes.

2. Y RNA Structure and Function

2.1. Y RNA Structure

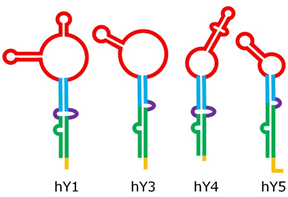

Despite their relatively short length, Y RNA have a complex 3-D structure, including both double-helix rigid stems and single-strand flexible loops [19]; their structure can be roughly split into five major regions, represented by different colors in Figure 2. These regions are responsible for the binding activity of Y RNA with proteins, such as the above mentioned RO60 (which binds the lower stem and the bulge) and SSB (which recognizes the polyU tail). It was shown that the tail may be a variable portion of Y RNA, at least in hY1 and hY3, and that this might influence their intracellular stability, it being a target of exonucleases [20]. The upper stem domain is important for DNA replication, while the loop domain performs different tasks, such as modulation of chromatin association, protein binding, and cleavage for the formation of YsRNA (Y RNA-derived small RNAs) [19][21][22].

Figure 2. Structure of human Y RNA. The structure was retrieved from the literature [19][21][22], but alternative structures with minor differences have been reported as well [23][24]. The domains are the poly-U tail (yellow), the lower stem (green), the bulge (violet), the upper stem (blue), and the loop (red).

2.2. Y RNA Interacting Proteins

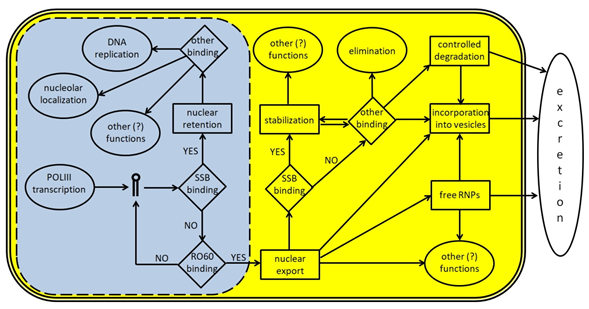

To date, several proteins have been identified that directly interact with either the entire Y RNA or Y RNA-derived fragments; the current knowledge about these interactions is summarized in Table 1, while the main steps in the life cycle of Y RNA are schematically depicted in Figure 3. It is likely that each Y RNA binds at the same time at least two proteins, one of which is a ‘core protein’ bound on the stem domain or the poly-U tail (such as RO60 or SSB) and another on the loop domain. Indeed, experiments using gel filtration show that Y-linked RNP range from 150 to 550 kDa (see [23] and references therein); this ample size variation likely reflects an equally ample variability in their composition. As shown in Table 1, the enrichment of RNA-processing/stabilizing proteins, including both sncRNA and mRNA is evident; this suggests that Y RNA have, potentially, multiple functions inside the cells, including the control of gene expression. This makes them promising potential targets for cancer therapy.

Table 1. Y RNA binding proteins. Data inside parentheses indicate unconfirmed data or minor effects. Protein names (column 1) are those approved by the HUGO (Human Genome Organization) Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC). Proteins are listed in alphabetical order according to data in column 1. References (refs) indicate the works that illustrate the protein binding to Y RNA (i.e., not the protein function). Y RNA between parentheses indicate weak or unconfirmed data; 1-3-4-5 is for hY1-hY3-hY4-hY5, respectively.

|

Protein (HGNC) |

Synonym(s) |

Interacting Y RNA |

Y RNA Domain Involved |

Protein Function |

Refs |

|

AGO1 |

EIF2C1, AGO |

unknown |

unknown |

gene silencing through RNAi |

[25] |

|

APOBEC3F |

ARP8 |

(1), (3), (4), (5) |

unknown |

antiviral activity |

|

|

APOBEC3G |

CEM15 |

1, 3, 4, 5 |

unknown |

antiviral activity |

|

|

CALR |

CR, CRT |

1, 3, 4, 5 |

unknown |

formation of the RO60 RNP complex, calcium-binding chaperone |

[28] |

|

CPSF1 |

CPSF160 |

1, 3 |

loop |

mRNA poly-adenylation |

[29] |

|

CPSF2 |

CPSF100 |

1, 3 |

loop |

mRNA poly-adenylation |

[29] |

|

CPSF4 |

NEB1 |

1, 3 |

loop |

histone pre-mRNA processing |

[29] |

|

DIS3 |

EXOSC11 |

(1), (3) |

polyU tail |

Y RNA stabilization |

[20] |

|

DIS3L |

DIS3L1 |

1, 3 |

polyU tail |

Y RNA degradation and turnover |

[20] |

|

EXOSC10 |

PMSCL2 |

1, 3, 4, 5 |

polyU tail |

Y RNA trimming, stabilization |

[20] |

|

ELAVL1 |

HuR |

3 |

unknown |

mRNA stabilization |

[29] |

|

ELAVL4 |

HuD |

3 |

loop |

mRNA stabilization, mRNA translation |

[30] |

|

FIP1L1 |

FIP1-like 1 |

1, 3 |

loop |

mRNA poly-adenylation |

[29] |

|

HNRNPK |

HNRPK |

1, 3 |

loop |

pre-mRNA binding |

[31] |

|

IFIT5 |

RI58 |

5 |

unknown |

innate immunity |

[32] |

|

MATR3 |

VCPDM |

1, 3 |

upper and lower stem |

nuclear matrix, transcription, RNA-editing |

|

|

MOV10 |

gb110, KIAA1631 |

unknown |

unknown |

microRNA-guided mRNA cleavage |

[34] |

|

NCL |

nucleolin, C23 |

1, 3 |

loop |

association with intranucleolar chromatin |

[35] |

|

PARN |

DAN |

1, 3, 4, 5 |

polyU tail |

Y RNA trimming, stabilization |

[20] |

|

PTBP1 |

hnRNP I, PTB |

1, 3 |

loop |

pre-mRNA splicing |

[31] |

|

PUF60 |

RoBPI, FIR |

(1), (3), 5 |

(loop) |

pre-mRNA splicing, apoptosis, transcription regulation |

|

|

RNASEL |

PRCA1, RNS4 |

1, (3), 4, 5 |

loop |

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis |

[37] |

|

RO60 |

TROVE2, SSA |

1, 3, 4, 5 |

lower stem |

stabilization, nuclear export, RNA quality control |

|

|

RPL5 |

L5 |

5 |

loop |

5S rRNA quality control |

[32] |

|

SSB |

La, LARP3 |

1, 3, 4, 5 |

polyU tail |

nuclear localization, protection of 3′ ends of pol-III transcripts |

[39] |

|

SYMPK |

SYM, SPK |

1, 3, (4), (5) |

loop |

mRNA poly-adenylation, histone pre-mRNA processing |

[29] |

|

TENT4B |

PAPD5 |

1, 3, 4, 5 |

polyU tail |

Y RNA oligoadenylation, degradation |

[20] |

|

TOE1 |

PCH7 |

1, (3) |

polyU tail |

Y RNA degradation and turnover |

[20] |

|

YBX1 |

NSEP1 |

1, 3, 4, (5) |

unknown |

mRNA transcription, splicing, translation, stability |

|

|

YBX3 |

DBPA |

unknown |

unknown |

cold-shock domain protein; DNA-binding domain protein |

[34] |

|

ZBP1 |

C20ORF183, IGF2BP1 |

(1), 3 |

loop |

nuclear export of RO60 and Y3 |

Figure 3. A schematic representation of Y RNA life cycle. The light blue area represents the nucleus (the dotted line indicates the presence of nuclear pores) and the molecular events occurring inside it; the yellow area represents the cytoplasm; the white space represents the surrounding extracellular environment. Y RNA are transcribed by POLIII and, if bound by SSB/La, may remain inside the nucleus to perform specific tasks like promoting DNA replication or other functions, upon binding to specific proteins such as those reported in Table 1. In many cases, these additional functions are not fully understood, since Y RNA binding companions are known, but not their role. If Y RNA are bound by RO60 inside the nucleus, they can be exported into the cytoplasm with the help of specific carrier proteins. Once there, Y RNA may perform several tasks, either alone or in RNP complexes. Y RNA may be stabilized through their binding to SSB, RO60, or other proteins, and they may contribute to the stabilization of several target molecules. Moreover, they may also be excreted in the extracellular environment either as free and complete RNA, or as free RNP complexes, or inside micro vesicles. Y RNA excretion may also occur after a specific cleavage, that generates the YsRNA. Once in the extracellular environment, Y RNA may be internalized by target cells to perform additional tasks.

2.3. Role of Y RNA in RO60 Function

A special consideration, among Y RNA interacting proteins, should be given to RO60. This protein is a ring-shaped polypeptide [42] that specifically uses Y RNA as a scaffolding element [43]. Once assembled, this RNP complex fulfills several intracellular tasks, such as RNA quality control [32][44], intracellular transport of RNA-binding proteins [45], and response to environmental stress (reviewed in [22][24]). RO60 is highly conserved [44][46], and its functions include the binding of aberrant or mis-folded non-coding RNAs (ncRNA) such as 5S rRNA or U2 snRNA [47][48]. Due to the very high binding affinity of Y RNA for RO60, some authors hypothesize that Y RNA might act as RO60 repressors [42][49], although some evidence supports the hypothesis that these molecules (or, at least, hY5) might also enhance the recognition of mis-folded ncRNA [32]. Data show that the assembly of Ro RNP protects the particle itself from degradation in several organisms [50]. In addition, RO60 intracellular localization (nucleus/cytoplasm) is also driven by its binding to Y RNA [38][44], possibly through its interaction with other proteins such as nucleolin (NCL), polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins (PTB), and Z-DNA binding protein 1 (ZBP1) [23].

2.4. Role of Y RNA in DNA Replication

The role of—at least some—Y RNA in the initiation of DNA replication and cell cycle progression is well established. RNA-mediated depletion (RNAi) has been successfully used to knock down the intracellular amount of hY1, hY3, and hY4, demonstrating that this treatment on any of those is sufficient to halt or strongly reduce both processes, while the artificial re-expression of any of them in the same cells is sufficient to restore a pre-treatment situation [51][52][53][54]. Similar results were achieved by Y RNA inactivation mediated by antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) micro-injected in vertebrate and worm embryos, causing their death [53][55]. The role of Y RNA in DNA replication is uncoupled from that of RO60 RNP; immuno-depletion in human cells of either RO60 or SSB is not sufficient to inhibit DNA replication [56] and the same happens in case of mutations deleting either the RO60 or SSB binding site inside Y RNA [18][57]. The additional finding that this process is driven by the upper stem domain of Y RNA [18] further supports the fact that Y RNA accomplish DNA replication independently of both RO60 and SSB, which have different binding sites (Table 1); moreover, it suggests that the initiation of DNA replication depends on different, yet currently unknown, binding proteins [57].

The different results obtained for hY5 (no effect on DNA replication upon RNAi treatment) may be explained in at least two ways. Some authors hypothesize that this Y RNA is just refractory to RNA-mediated depletion [51][52]. Alternatively, hY5 might play a marginal role in this process; this is suggested by its different intranuclear localization: hY1, hY3, and hY4 co-localize on early-replicating euchromatin, while hY5 is mostly localized inside nucleoli [58].

The role of Y RNA in promoting the initiation of DNA replication is in good agreement with their overexpression in various human solid tumors [52] (see also Section 3).

2.5. Y RNA Derivatives and Fragments

During the apoptosis, the RNA component of Ro RNP is partly degraded, generating the Y RNA-derived small RNAs (YsRNA); however, Dicer is not involved in their formation, thus their origin and function is not related to those of micro-RNAs [59][60]. These shorter fragments are specifically, abundantly, and rapidly generated from all four Y RNA through the action of caspases [61], yet their causal role in these phenomena (apoptosis and miR biogenesis), if any, is currently unclear [61][62]. These fragments remain bound to the RO60 protein and, in part, also to the SSB protein [61] suggesting their formation occurs early during the apoptotic process. YsRNA have been identified both in healthy tissues [33][59] and in cancer cells. These fragments—especially those derived from hY4—are particularly abundant in plasma, serum [63][64][65], and other biofluids [66][67], where they circulate either as free complexes with a mass between 100 and 300 kDa, or in exosomes and microvesicles [63], collectively called ‘extracellular vesicles’ (EV). Some authors suggest that Y RNA and their derivatives might also fulfill a signaling [63] or a gene regulation [68] function and act also on distant targets.

3. Y RNA and Human Cancer

The first comprehensive report about Y RNA quantification in human cancers was published by Christov and collaborators in 2008 [52] and, to date, it is still a major reference in this field. The examined solid tumors were carcinomas and adenocarcinomas of the lung, kidney, bladder, prostate, colon, and cervix. As a general rule, the authors showed that all four Y RNA are overexpressed, with a range between 4- and 13-fold (for hY4 and hY1, respectively). Despite its importance, the results of this work have been challenged by some authors in the last years, especially as for bladder and prostate cancers, while in other cases the results were only partially replicated. The major points of contrast are the choice of proliferation biomarkers, the missing differentiation of subtypes of cancer samples, the low numbers of tumor and control samples and the lack of distinction between the intracellular and extracellular—either free or embedded inside EV—amount of Y RNA. However, there are some points that have been lately confirmed by other studies, thus supporting the validity of this study [52], at least as a pilot. First, in all tumors analyzed and reported below, Y RNA expression is altered. Second, expression levels of Y RNA vary with tissue type, and there are patterns of mis-expression that are tissue-specific. Third, while the expression of hY1, hY3, and hY4 RNA are to some extent linked, the expression of hY5 RNA is somehow unlinked to the others, at least in some cancer types.

In 2010 Meiri and collaborators further analyzed the sncRNA profile of several solid tumor types [62]. In addition, this work suffers from evident limitations, the most important being the low sample number (in many cases this number is not reported), the non-fresh sources used for RNA quantification (23 human formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples), and the poor characterization of tumor histology (some samples, like lung, are a mix of various tumor types). Consequently, the study of Meiri et al. [62] should be considered a pilot study, similarly to [52].

Table 2 summarizes the present knowledge about Y RNA expression and tumor types/subtypes.

Table 2. Expression levels of Y RNA in various cancer types. Cancers are listed in alphabetical order according to the affected organ, irrespective of their histology, for which we refer the reader to the main text; KS means Kaposi’s sarcoma, a multi-organ cancer. The word ‘serum’ is used for short to indicate blood serum. An arrow pointing upward means overexpression; an arrow pointing downward means under-expression; a horizontal, double-headed arrow indicates no significant change; arrows between parentheses indicate weak evidence; mix indicates a complex situation with up- and down-regulation at the same time. N/A means that no data are available. Refs indicates bibliographic references, while ref gene indicates the gene(s) used for quantitative comparison. See the text for further details. Notes to Table2. FFPE are formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor cells from stored samples of various ages; PE are paraffin-embedded cells from fresh samples. qRT-PCR is quantitative Real Time PCR; HTS is high throughput sequencing. (a): the authors used simultaneously three methods (high throughput sequencing, microarray analysis and qRT-PCR) and compared the obtained results. 1: differences between EV and cancer cells; 2: differential up- and down-regulation (see text); 3: differences between blood serum and cells.

| Cancer | hY1 | hY3 | hY4 | hY5 | Refs | Sample Type | Sample Number | Control Number | Method | Ref Gene | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bladder | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | (↑) | [52] | cell cultures | 4 | 4 | qRT-PCR | Ki-67, HPRT1 | |

| ↑ | ↑ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | 5 | 1 | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [69] | FFPE | 88 | 30 | qRT-PCR | SNORD43, RNU6-2 | ||

| blood | N/A | N/A | N/A | ↑ | [70] | K562 cells EV | N/A | N/A | RNA-seq | N/A | 1 |

| (↑) | N/A | ↑ | N/A | [71] | plasma EV | N/A | N/A | RNA-seq | N/A | 1 | |

| brain | ↑ | ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | [72] | cell culture EV, free RNP | N/A | N/A | RNA-seq | N/A | |

| breast | ↑ | ↑ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | 5 | N/A | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | |

| mix | mix | mix | mix | [73] | serum | 5 | 5 | RNA-seq | N/A | 2 | |

| N/A | N/A | ↑ | N/A | [74] | cell culture EV, free RNP | N/A | N/A | RNA-seq | N/A | ||

| ↑ | N/A | ↑ | ↑ | [75] | cell lines | 26 | N/A | RNA-seq | N/A | ||

| cervix | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [52] | cell cultures | 4 | 4 | qRT-PCR | Ki-67, HPRT1 | |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | ↑ | [59] | HeLa cells | N/A | N/A | northern blotting | N/A | ||

| ↑ | (↑) | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | N/A | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | ||

| colon | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [52] | cell cultures | 8 | 4 | qRT-PCR | Ki-67, HPRT1 | |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | ↑ | [59] | HeLa cells | N/A | N/A | northern blotting | N/A | ||

| ↑ | ↔ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | 7 | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | ||

| N/A | N/A | ↑ | N/A | [76] | PE | 96 | N/A | HTS | miR-128a-3p, miR-92a-3p, miR-151a-3p |

||

| esophagus | (↑) | ↔ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | N/A | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | |

| head/neck | mix | mix | mix | mix | [77] | serum | N/A | N/A | RNA-seq | N/A | 2 |

| mix | mix | mix | mix | [78] | serum, tumor tissue | 5+2 | 5+2 | qRT-PCR | β2-microglobulin | 2 | |

| kidney | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [52] | cell cultures | 15 | 4 | qRT-PCR | Ki-67, HPRT1 | 3 |

| ↔ | ↔ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | N/A | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | ||

| ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | [79] | tissue, serum | 30+88 | 15+59 | qRT-PCR | SNORD43 | ||

| liver | ↑ | ↔ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | 3 | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | |

| lymphatic system | N/A | N/A | ↑ | N/A | [80] | fresh, cell lines | 20+5+44 | 5+19 | RNA-seq | N/A | |

| lung | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | ↑ | [52] | cell cultures | 6 | 4 | qRT-PCR | Ki-67, HPRT1 | 1 |

| ↑ | ↑ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | 6 | 4 | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | 1 | |

| N/A | N/A | ↑ | N/A | [81] | plasma EV, cell cultures | 44+31 | 17 | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR | U6 snRNA | ||

| ovary | ↑ | ↔ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | N/A | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | |

| pancreas | ↑ | ↑ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | N/A | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | |

| prostate | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | (↑) | [52] | cell cultures | 5 | 4 | qRT-PCR | Ki-67, HPRT1 | |

| ↔ | ↑ | N/A | N/A | [62] | FFPE | N/A | N/A | (a) | hsa-miR-200b | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [82] | FFPE | 56 | 36+28 | qRT-PCR | SNORD43, RNU6-2 | ||

| skin | ↑ | (↑) | ↑ | ↑ | [83] | MML-1 cells | N/A | N/A | RNA-seq | N/A | 1 |

| ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N/A | [84] | plasma EV | 118 | 99 | RNA-seq, ddPCR | N/A | 1 | |

| KS | ↑ | (↑) | ↑ | ↑ | [85] | plasma EV | 8+28 | 19 | RNA-seq | N/A | 1 |

| ↑ | N/A | ↑ | N/A | [86] | plasma EV | N/A | N/A | RNA-Seq | N/A | 1 |

4. Conclusions

The differential expression of Y RNA among different tissues, across different tumors and, sometimes, also between tumor cells and their released EV (Table 2) support their possible use in the identification and characterization of tumors, often without the use of invasive biopsies, but through a simple analysis of bodily fluids. However, this potential diagnostic strength is balanced by the complexity of Y RNA quantification demonstrated by the available literature, where several different approaches have been used to address this topic (Table 2). Further analysis of these elusive molecules in larger cohorts and the use of robust protocols may shed a new light in our understanding of Y RNA function in human cancers.

References

- M. Lerner; J. Boyle; J. Hardin; J. Steitz; Two novel classes of small ribonucleoproteins detected by antibodies associated with lupus erythematosus. Science 1981, 211, 400-402, 10.1126/science.6164096.

- S. L. Deutscher; J. B. Harley; J. D. Keene; Molecular analysis of the 60-kDa human Ro ribonucleoprotein.. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1988, 85, 9479-9483, 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9479.

- E Ben-Chetrit; B J Gandy; E M Tan; Kevin F. Sullivan; Isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding the 60-kD component of the human SS-A/Ro ribonucleoprotein autoantigen.. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1989, 83, 1284-1292, 10.1172/jci114013.

- J C Chambers; D Kenan; B J Martin; J D Keene; Genomic structure and amino acid sequence domains of the human La autoantigen.. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1988, 263, 18043-51.

- J P Hendrick; Sandra L. Wolin; J Rinke; M R Lerner; J A Steitz; Ro small cytoplasmic ribonucleoproteins are a subclass of La ribonucleoproteins: further characterization of the Ro and La small ribonucleoproteins from uninfected mammalian cells.. Molecular and Cellular Biology 1981, 1, 1138-1149, 10.1128/mcb.1.12.1138.

- Sandra L. Wolin; Joan A. Steitz; Genes for two small cytoplasmic Ro RNAs are adjacent and appear to be single-copy in the human genome. Cell 1983, 32, 735-744, 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90059-4.

- Richard J. Maraia; Gene encoding human Ro-associated autoantigen Y5 RNA. Nucleic Acids Research 1996, 24, 3552-3559, 10.1093/nar/24.18.3552.

- Richard J. Maraia; Noriko Sasaki-Tozawa; Claire T. Driscoll; Eric D. Green; Gretchen J. Darlington; The human Y4 small cytoplasmic RNA gene is controlled by upstream elements and resides on chromosome 7 with all other hY scRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research 1994, 22, 3045-3052, 10.1093/nar/22.15.3045.

- Jean-Pierre Perreault; Jean-François Noël; Francis Brière; Benoit Cousineau; Jean-François Lucier; Gilles Boire; Retropseudogenes derived from the human Ro/SS-A autoantigen-associated hY RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2005, 33, 2032-2041, 10.1093/nar/gki504.

- Fabrizio Signore; Caterina Gulìa; Raffaella Votino; Vincenzo De Leo; Simona Zaami; Lorenza Putignani; Silvia Gigli; Edoardo Santini; Luca Bertacca; Alessandro Porrello; et al.Roberto Piergentili The Role of Number of Copies, Structure, Behavior and Copy Number Variations (CNV) of the Y Chromosome in Male Infertility. Genes 2019, 11, 40, 10.3390/genes11010040.

- Jonathan Perreault; Jean-Pierre Perreault; Gilles Boire; Ro-Associated Y RNAs in Metazoans: Evolution and Diversification. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2007, 24, 1678-1689, 10.1093/molbev/msm084.

- Ilenia Boria; Andreas R. Gruber; Andrea Tanzer; Stephan H. F. Bernhart; Ronny Lorenz; Michael M. Mueller; Ivo L. Hofacker; Peter F. Stadler; Nematode sbRNAs: Homologs of Vertebrate Y RNAs. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2010, 70, 346-358, 10.1007/s00239-010-9332-4.

- Francisco Ferreira Duarte Junior; Paulo Sérgio Alves Bueno; Sofia L. Pedersen; Fabiana Dos Santos Rando; José Renato Pattaro Júnior; Daniel Caligari; Anelise Cardoso Ramos; Lorena Gomes Polizelli; Ailson Francisco Dos Santos Lima; Quirino Alves De Lima Neto; et al.T. KrudeFlavio Augusto Vicente SeixasMaria Aparecida Fernandez Identification and characterization of stem-bulge RNAs in Drosophila melanogaster. RNA Biology 2019, 16, 330-339, 10.1080/15476286.2019.1572439.

- Francisco Ferreira Duarte Junior; Quirino Alves De Lima Neto; Fabiana Rando; Douglas Vinícius Bassalobre De Freitas; José Renato Pattaro Júnior; Lorena Gomes Polizelli; Roxelle Ethienne Ferreira Munhoz; Flavio Augusto Vicente Seixas; M. A. Fernandez; Identification and molecular structure analysis of a new noncoding RNA, a sbRNA homolog, in the silkworm Bombyx mori genome. Mol. BioSyst. 2015, 11, 801-808, 10.1039/c4mb00595c.

- Axel Mosig; Meng Guofeng; Bärbel M. R. Stadler; Peter F Stadler; Evolution of the vertebrate Y RNA cluster. Theory in Biosciences 2007, 126, 9-14, 10.1007/s12064-007-0003-y.

- A.Darise Farris; Joanne K. Gross; Jay S. Hanas; John B. Harley; Genes for murine Y1 and Y3 Ro RNAs have Class 3 RNA polymerase III promoter structures and are unlinked on mouse chromosome 6. Gene 1996, 174, 35-42, 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00279-x.

- C. A. O'brien; K. Margelot; Sandra L. Wolin; Xenopus Ro ribonucleoproteins: members of an evolutionarily conserved class of cytoplasmic ribonucleoproteins.. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 7250-7254, 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7250.

- Timothy J. Gardiner; Christo P. Christov; Alexander R. Langley; T. Krude; A conserved motif of vertebrate Y RNAs essential for chromosomal DNA replication. RNA 2009, 15, 1375-1385, 10.1261/rna.1472009.

- S. W. M. Teunissen; Conserved features of Y RNAs: a comparison of experimentally derived secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28, 610-619, 10.1093/nar/28.2.610.

- Siddharth Shukla; Roy Parker; PARN Modulates Y RNA Stability and Its 3′-End Formation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2017, 37, e00264-17, 10.1128/mcb.00264-17.

- Celia W. G. Van Gelder; José P.H.M. Thijssen; Erik C.J. Klaassen; Christine Sturchler; Alain Krol; J. Van Walther; Ger J.M. Pruijn; Common structural features of the Ro RNP associated hY1 and hY5 RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 1994, 22, 2498-2506, 10.1093/nar/22.13.2498.

- Madzia P. Kowalski; Torsten Krude; Functional roles of non-coding Y RNAs. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2015, 66, 20-29, 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.07.003.

- Marcel Köhn; Nikolaos Pazaitis; Stefan Hüttelmaier; Why YRNAs? About Versatile RNAs and Their Functions. Biomolecules 2013, 3, 143-156, 10.3390/biom3010143.

- Marco Boccitto; Sandra L. Wolin; Ro60 and Y RNAs: Structure, Functions and Roles in Autoimmunity. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2019, 54, 133-152, 10.1080/10409238.2019.1608902.

- Daniel W. Thomson; Katherine A. Pillman; Matthew L. Anderson; David M. Lawrence; John Toubia; Gregory Goodall; Cameron Bracken; Assessing the gene regulatory properties of Argonaute-bound small RNAs of diverse genomic origin.. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 43, 470-81, 10.1093/nar/gku1242.

- Sarah Gallois-Montbrun; Rebecca K. Holmes; Chad M. Swanson; Mireia Fernández-Ocaña; Helen L. Byers; Malcolm A Ward; Michael H. Malim; Comparison of Cellular Ribonucleoprotein Complexes Associated with the APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G Antiviral Proteins. Journal of Virology 2008, 82, 5636-5642, 10.1128/jvi.00287-08.

- Tao Wang; Chunjuan Tian; Wenyan Zhang; Kun Luo; Phuong Thi Nguyen Sarkis; Lillian Yu; Bindong Liu; Yunkai Yu; Xiao-Fang Yu; 7SL RNA Mediates Virion Packaging of the Antiviral Cytidine Deaminase APOBEC3G. Journal of Virology 2007, 81, 13112-13124, 10.1128/jvi.00892-07.

- S T Cheng; T Q Nguyen; Y S Yang; J D Capra; R D Sontheimer; Calreticulin binds hYRNA and the 52-kDa polypeptide component of the Ro/SS-A ribonucleoprotein autoantigen.. The Journal of Immunology 1996, 156, 4484-4491.

- Marcel Köhn; Christian Ihling; Andrea Sinz; Knut Krohn; Stefan Hüttelmaier; The Y3** ncRNA promotes the 3′ end processing of histone mRNAs. Genes & Development 2015, 29, 1998-2003, 10.1101/gad.266486.115.

- Toma Tebaldi; Paola Zuccotti; Daniele Peroni; Marcel Köhn; Lisa Gasperini; Valentina Potrich; Veronica Bonazza; Tatiana Dudnakova; Annalisa Rossi; Guido Sanguinetti; et al.Luciano ContiPaolo MacchiVito D’AgostinoGabriella VieroDavid TollerveyStefan HüttelmaierAlessandro Quattrone HuD Is a Neural Translation Enhancer Acting on mTORC1-Responsive Genes and Counteracted by the Y3 Small Non-coding RNA.. Molecular Cell 2018, 71, 256-270.e10, 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.06.032.

- Gustáv Fabini; Reinout Raijmakers; Silvia Hayer; Michael A. Fouraux; Ger J. M. Pruijn; G Steiner; The Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoproteins I and K Interact with a Subset of the Ro Ribonucleoprotein-associated Y RNAsin Vitroandin Vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 20711-20718, 10.1074/jbc.m101360200.

- J. Robert Hogg; Kathleen Collins; Human Y5 RNA specializes a Ro ribonucleoprotein for 5S ribosomal RNA quality control. Genes & Development 2007, 21, 3067-3072, 10.1101/gad.1603907.

- Fumiyoshi Yamazaki; Hyun Hee Kim; Pierre Lau; Christopher K. Hwang; P. Michael Iuvone; David C. Klein; Samuel J. Clokie; pY RNA1-s2: A Highly Retina-Enriched Small RNA That Selectively Binds to Matrin 3 (Matr3). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88217, 10.1371/journal.pone.0088217.

- Soyeong Sim; Jie Yao; David E. Weinberg; Sherry Niessen; John R. Yates; Sandra L. Wolin; The zipcode-binding protein ZBP1 influences the subcellular location of the Ro 60-kDa autoantigen and the noncoding Y3 RNA. RNA 2011, 18, 100-110, 10.1261/rna.029207.111.

- Michael A. Fouraux; Philippe Bouvet; Sjoerd Verkaart; Walther J. Van Venrooij; Ger J. M. Pruijn; Nucleolin Associates with a Subset of the Human Ro Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Journal of Molecular Biology 2002, 320, 475-488, 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00518-1.

- Pascal Bouffard; Elie Barbar; Francis Brière; Gilles Boire; Interaction cloning and characterization of RoBPI, a novel protein binding to human Ro ribonucleoproteins. RNA 2000, 6, 66-78, 10.1017/s1355838200990277.

- Jesse Donovan; Sneha Rath; David Kolet-Mandrikov; Alexei Korennykh; Rapid RNase L–driven arrest of protein synthesis in the dsRNA response without degradation of translation machinery. RNA 2017, 23, 1660-1671, 10.1261/rna.062000.117.

- Soyeong Sim; David E. Weinberg; Gabriele Fuchs; Keum Choi; Jina Chung; Sandra L. Wolin; The Subcellular Distribution of an RNA Quality Control Protein, the Ro Autoantigen, Is Regulated by Noncoding Y RNA Binding. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2009, 20, 1555-1564, 10.1091/mbc.e08-11-1094.

- F H Simons; S A Rutjes; W J Van Venrooij; G J Pruijn; The interactions with Ro60 and La differentially affect nuclear export of hY1 RNA.. RNA 1996, 2, 264-273.

- Saskia A. Rutjes; Elsebet Lund; Annemarie Van Der Heijden; Christian Grimm; Walther J. Van Venrooij; Ger J. M. Pruijn; Identification of a novel cis-acting RNA element involved in nuclear export of hY RNAs.. RNA 2001, 7, 741-752, 10.1017/s1355838201002503.

- Marcel Köhn; Marcell Lederer; Kristin Wächter; Stefan Hüttelmaier; Near-infrared (NIR) dye-labeled RNAs identify binding of ZBP1 to the noncoding Y3-RNA. RNA 2010, 16, 1420-1428, 10.1261/rna.2152710.

- Adam J. Stein; Gabriele Fuchs; Chunmei Fu; Sandra L. Wolin; Karin M. Reinisch; Structural insights into RNA quality control: the Ro autoantigen binds misfolded RNAs via its central cavity.. Cell 2005, 121, 529-539, 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.009.

- Hendrik Täuber; Stefan Hüttelmaier; Marcel Köhn; POLIII-derived non-coding RNAs acting as scaffolds and decoys. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology 2019, 11, 880-885, 10.1093/jmcb/mjz049.

- Soyeong Sim; Sandra L. Wolin; Emerging roles for the Ro 60-kDa autoantigen in noncoding RNA metabolism. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 2011, 2, 686-699, 10.1002/wrna.85.

- Aurélia Belisova; Katharina Semrad; Oliver Mayer; Grazia Kocian; Elisabeth Waigmann; Renée Schroeder; G Steiner; RNA chaperone activity of protein components of human Ro RNPs. RNA 2005, 11, 1084-1094, 10.1261/rna.7263905.

- Sandra L. Wolin; C. Belair; Marco Boccitto; Xinguo Chen; Soyeong Sim; David W Taylor; Hong-Wei Wang; Non-coding Y RNAs as tethers and gates. RNA Biology 2013, 10, 1602-1608, 10.4161/rna.26166.

- Xinguo Chen; James D. Smith; Hong Shi; Derek D. Yang; Richard A. Flavell; Sandra L. Wolin; The Ro Autoantigen Binds Misfolded U2 Small Nuclear RNAs and Assists Mammalian Cell Survival after UV Irradiation. Current Biology 2003, 13, 2206-2211, 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00870-4.

- C A O'brien; S L Wolin; A possible role for the 60-kD Ro autoantigen in a discard pathway for defective 5S rRNA precursors.. Genes & Development 1994, 8, 2891-2903, 10.1101/gad.8.23.2891.

- Gabriele Fuchs; Adam J Stein; Chunmei Fu; Karin M Reinisch; Sandra L. Wolin; Structural and biochemical basis for misfolded RNA recognition by the Ro autoantigen. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2006, 13, 1002-1009, 10.1038/nsmb1156.

- Xinguo Chen; Sandra L. Wolin; The Ro 60�kDa autoantigen: insights into cellular function and role in autoimmunity. Journal of Molecular Medicine 2004, 82, 232-239, 10.1007/s00109-004-0529-0.

- Christo P. Christov; Timothy J. Gardiner; Dávid Szüts; T. Krude; Functional Requirement of Noncoding Y RNAs for Human Chromosomal DNA Replication. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2006, 26, 6993-7004, 10.1128/MCB.01060-06.

- C P Christov; E Trivier; T. Krude; Noncoding human Y RNAs are overexpressed in tumours and required for cell proliferation. British Journal of Cancer 2008, 98, 981-988, 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604254.

- Clara Collart; Christo P. Christov; James C. Smith; T. Krude; The Midblastula Transition Defines the Onset of Y RNA-Dependent DNA Replication in Xenopus laevis ▿. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2011, 31, 3857-3870, 10.1128/MCB.05411-11.

- T. Krude; Christo P. Christov; Olivier Hyrien; Kathrin Marheineke; Y RNA functions at the initiation step of mammalian chromosomal DNA replication. Journal of Cell Science 2009, 122, 2836-2845, 10.1242/jcs.047563.

- Madzia P. Kowalski; Howard A. Baylis; T. Krude; Non-coding stem-bulge RNAs are required for cell proliferation and embryonic development in C. elegans.. Journal of Cell Science 2015, 128, 2118-29, 10.1242/jcs.166744.

- Alexander R. Langley; Helen Chambers; Christo P. Christov; T. Krude; Ribonucleoprotein Particles Containing Non-Coding Y RNAs, Ro60, La and Nucleolin Are Not Required for Y RNA Function in DNA Replication. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13673, 10.1371/journal.pone.0013673.

- Iren Wang; Madzia P. Kowalski; Alexander R. Langley; Raphaël Rodriguez; Shankar Balasubramanian; Shang-Te Danny Hsu; Torsten Krude; Nucleotide Contributions to the Structural Integrity and DNA Replication Initiation Activity of Noncoding Y RNA. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 5848-5863, 10.1021/bi500470b.

- Alice Tianbu Zhang; Alexander R. Langley; Christo P. Christov; Eyemen Kheir; Thomas Shafee; Timothy J. Gardiner; T. Krude; Dynamic interaction of Y RNAs with chromatin and initiation proteins during human DNA replication.. Journal of Cell Science 2011, 124, 2058-69, 10.1242/jcs.086561.

- Francisco Esteban Nicolas; Adam E. Hall; Tibor Csorba; Carly Turnbull; Tamas Dalmay; Biogenesis of Y RNA-derived small RNAs is independent of the microRNA pathway. FEBS Letters 2012, 586, 1226-1230, 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.026.

- David Langenberger; M. Volkan Çakir; Steve Hoffmann; Peter F. Stadler; Dicer-Processed Small RNAs: Rules and Exceptions. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 2012, 320, 35-46, 10.1002/jez.b.22481.

- Saskia A. Rutjes; Annemarie Van Der Heijden; Paul J. Utz; W J Van Venrooij; Ger J. M. Pruijn; Rapid nucleolytic degradation of the small cytoplasmic Y RNAs during apoptosis.. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 24799-24807, 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24799.

- Eti Meiri; Asaf Levy; Hila Benjamin; Miriam Ben-David; Lahav Cohen; Avital Dov; Nir Dromi; Eran Elyakim; Noga Yerushalmi; Orit Zion; et al.Gila Lithwick-YanaiEinat Sitbon Discovery of microRNAs and other small RNAs in solid tumors. Nucleic Acids Research 2010, 38, 6234-6246, 10.1093/nar/gkq376.

- Joseph M. Dhahbi; Stephen R. Spindler; Hani Atamna; Dario Boffelli; Patricia Mote; David I. K. Martin; 5′-YRNA fragments derived by processing of transcripts from specific YRNA genes and pseudogenes are abundant in human serum and plasma. Physiological Genomics 2013, 45, 990-998, 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00129.2013.

- Ashish Yeri; Amanda Courtright; Rebecca Reiman; Elizabeth Carlson; Taylor Beecroft; Alex Janss; Ashley Siniard; Ryan Richholt; Chris Balak; Joel Rozowsky; et al.Robert KitchenElizabeth HutchinsJoseph WinartaRoger McCoyMatthew AnastasiSeungchan KimMatthew HuentelmanKendall Van Keuren-Jensen Total Extracellular Small RNA Profiles from Plasma, Saliva, and Urine of Healthy Subjects. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, srep44061, 10.1038/srep44061.

- Sinan Uğur Umu; Hilde Langseth; Cecilie Bucher-Johannessen; Bastian Fromm; Andreas Keller; Eckart Meese; Marianne Lauritzen; Magnus Leithaug; Robert Lyle; Trine B. Rounge; et al. A comprehensive profile of circulating RNAs in human serum. RNA Biology 2017, 15, 242-250, 10.1080/15476286.2017.1403003.

- Paula M. Godoy; Nirav R. Bhakta; Andrea J. Barczak; Hakan Cakmak; Susan Fisher; Tippi C. MacKenzie; Tushar Patel; Richard W. Price; James F. Smith; Prescott G. Woodruff; et al.David J. Erle Large Differences in Small RNA Composition Between Human Biofluids. Cell Reports 2018, 25, 1346-1358, 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.014.

- Lucia Vojtech; Sangsoon Woo; Sean Hughes; Claire Levy; Lamar Ballweber; Renan P. Sauteraud; Johanna Strobl; Katharine Westerberg; Raphael Gottardo; Muneesh Tewari; et al.Florian Hladik Exosomes in human semen carry a distinctive repertoire of small non-coding RNAs with potential regulatory functions. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, 7290-7304, 10.1093/nar/gku347.

- Bas W. M. Van Balkom; Almut S. Eisele; D. Michiel Pegtel; Sander Bervoets; Marianne C. Verhaar; Quantitative and qualitative analysis of small RNAs in human endothelial cells and exosomes provides insights into localized RNA processing, degradation and sorting. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2015, 4, 26760, 10.3402/jev.v4.26760.

- Yuri Tolkach; Anna Franziska Stahl; Eva-Maria Niehoff; Chenming Zhao; Glen Kristiansen; Stefan Müller; J. Ellinger; YRNA expression predicts survival in bladder cancer patients.. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 749, 10.1186/s12885-017-3746-y.

- Sudipto K. Chakrabortty; Ashwin Prakash; Gal Nechooshtan; Stephen Hearn; Thomas R. Gingeras; Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of processed and functional RNY5 RNA.. RNA 2015, 21, 1966-79, 10.1261/rna.053629.115.

- Franziska Haderk; Ralph Schulz; Murat Iskar; Laura Llaó Cid; Thomas Worst; Karolin V. Willmund; Angela Schulz; Uwe Warnken; Jana Seiler; Axel Benner; et al.Michelle NesslingThorsten ZenzMaria GöbelJan DürigSven DiederichsJérôme PaggettiEtienne MoussayStephan StilgenbauerMarc ZapatkaPeter LichterMartina Seiffert Tumor-derived exosomes modulate PD-L1 expression in monocytes. Science Immunology 2017, 2, eaah5509, 10.1126/sciimmunol.aah5509.

- Zhiyun Wei; Arsen O. Batagov; Sergio Schinelli; Jintu Wang; Yang Wang; Rachid El Fatimy; Rosalia Rabinovsky; Leonora Balaj; Clark C. Chen; Fred Hochberg; et al.Bob CarterXandra O. BreakefieldAnna M. Krichevsky Coding and noncoding landscape of extracellular RNA released by human glioma stem cells. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 1-15, 10.1038/s41467-017-01196-x.

- Joseph M. Dhahbi; Stephen R. Spindler; Hani Atamna; Dario Boffelli; David I.K. Martin; Deep Sequencing of Serum Small RNAs Identifies Patterns of 5′ tRNA Half and YRNA Fragment Expression Associated with Breast Cancer. Biomarkers in Cancer 2014, 6, BIC.S20764-47, 10.4137/bic.s20764.

- Juan Pablo Tosar; Fabiana Gámbaro; Julia Sanguinetti; Braulio Bonilla; Kenneth W. Witwer; Alfonso Cayota; Assessment of small RNA sorting into different extracellular fractions revealed by high-throughput sequencing of breast cell lines. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43, 5601-5616, 10.1093/nar/gkv432.

- Yan Guo; Hui Yu; Jing Wang; Quanhu Sheng; Shilin Zhao; Ying-Yong Zhao; Brian D. Lehmann; The Landscape of Small Non-Coding RNAs in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Genes 2018, 9, 29, 10.3390/genes9010029.

- Robin Mjelle; Kjersti Sellæg; Pål Sætrom; Liv Thommesen; Wenche Sjursen; Eva Hofsli; Identification of metastasis-associated microRNAs in serum from rectal cancer patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 90077-90089, 10.18632/oncotarget.21412.

- Berta Victoria Martinez; Joseph M. Dhahbi; Yury O. Nunez Lopez; Katarzyna Lamperska; Paweł Golusinski; Lukasz Luczewski; Tomasz Kolenda; Hani Atamna; Stephen R. Spindler; Wojciech Golusinski; et al.Michal M. Masternak Circulating small non coding RNA signature in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 19246-19263, 10.18632/oncotarget.4266.

- Joseph M Dhahbi; Yury O. Nunez Lopez; Augusto Schneider; Berta Victoria; Tatiana Saccon; Krish Bharat; Thaddeus McClatchey; Hani Atamna; Wojciech Scierski; Pawel Golusinski; et al.Wojciech GolusinskiMichal M. Masternak Profiling of tRNA Halves and YRNA Fragments in Serum and Tissue From Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients Identify Key Role of 5′ tRNA-Val-CAC-2-1 Half. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9, 959, 10.3389/fonc.2019.00959.

- Malin Nientiedt; Doris Schmidt; Glen Kristiansen; Stefan C. Müller; Jörg Ellinger; YRNA Expression Profiles are Altered in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. European Urology Focus 2018, 4, 260-266, 10.1016/j.euf.2016.08.004.

- Federica Lovisa; Piero Di Battista; Enrico Gaffo; Carlotta C. Damanti; Anna Garbin; Ilaria Gallingani; Elisa Carraro; Marta Pillon; Alessandra Biffi; Stefania Bortoluzzi; et al.Lara Mussolin RNY4 in Circulating Exosomes of Patients With Pediatric Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: An Active Player?. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10, 238, 10.3389/fonc.2020.00238.

- Chuang Li; Fang Qin; Fen Hu; Hui Xu; Guihong Sun; Guang Han; Tao Wang; Mingxiong Guo; Characterization and selective incorporation of small non-coding RNAs in non-small cell lung cancer extracellular vesicles. Cell & Bioscience 2018, 8, 2, 10.1186/s13578-018-0202-x.

- Yuri Tolkach; Eva-Maria Niehoff; Anna Franziska Stahl; Chenming Zhao; Glen Kristiansen; Stefan C. Müller; J. Ellinger; YRNA expression in prostate cancer patients: diagnostic and prognostic implications. World Journal of Urology 2018, 36, 1073-1078, 10.1007/s00345-018-2250-6.

- Taral R Lunavat; Lesley Cheng; Dae-Kyum Kim; Joydeep Bhadury; Su Chul Jang; Cecilia Lässer; Robyn A Sharples; Marcela Dávila López; Jonas Nilsson; Yong Song Gho; et al.Andrew F HillJan Lötvall Small RNA deep sequencing discriminates subsets of extracellular vesicles released by melanoma cells – Evidence of unique microRNA cargos. RNA Biology 2015, 12, 810-823, 10.1080/15476286.2015.1056975.

- Carla Solé; Daniela Tramonti; Maike Schramm; Ibai Goicoechea; María Armesto; Luiza I. Hernandez; Lorea Manterola; Marta Fernandez-Mercado; Karmele Mujika; Anna Tuneu; et al.Ane JakaMaitena TellaetxeMarc R. FriedländerXavier EstivillPaolo PiazzaPablo L. Ortiz-RomeroMark R. MiddletonCharles H. Lawrie The Circulating Transcriptome as a Source of Biomarkers for Melanoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 70, 10.3390/cancers11010070.

- Minako Ikoma; Soren Gantt; Corey Casper; Yuko Ogata; Qing Zhang; Ryan Basom; Michael R. Dyen; Timothy M. Rose; Serge Barcy; KSHV oral shedding and plasma viremia result in significant changes in the extracellular tumorigenic miRNA expression profile in individuals infected with the malaria parasite. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192659, 10.1371/journal.pone.0192659.

- Kehinde Babatunde; Smart Mbagwu; María Andrea Hernández-Castañeda; Swamy Rakesh Adapa; Michael Walch; Luis Filgueira; Laurent Falquet; Rays H. Y. Jiang; Ionita Ghiran; Pierre-Yves Mantel; et al. Malaria infected red blood cells release small regulatory RNAs through extracellular vesicles. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 884, 10.1038/s41598-018-19149-9.