| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 3950 | 2022-10-08 05:42:58 |

Video Upload Options

The Phanerozoic Eon is the current geologic eon in the geologic time scale, and the one during which abundant animal and plant life has existed. It covers 541 million years to the present and began with the Cambrian Period when animals first developed hard shells preserved in the fossil record. The time before the Phanerozoic, called the Precambrian, is now divided into the Hadean, Archaean and Proterozoic eons. The time span of the Phanerozoic starts with the sudden appearance of fossilized evidence of a number of animal phyla; the evolution of those phyla into diverse forms; the emergence and development of complex plants; the evolution of fish; the emergence of insects and tetrapods; and the development of modern fauna. Plant life on land appeared in the early Phanerozoic eon. During this time span, tectonic forces caused the continents to move and eventually collect into a single landmass known as Pangaea (the most recent supercontinent), which then separated into the current continental landmasses.

1. Etymology of the Term

Its name was derived from the Ancient Greek words φανερός (phanerós) and ζωή (zōḗ), meaning visible life, since it was once believed that life began in the Cambrian, the first period of this eon. The term "Phanerozoic" was coined in 1930 by the American geologist George Halcott Chadwick (1876–1953).[1][2]

2. Proterozoic-Phanerozoic Boundary

The Proterozoic-Phanerozoic boundary is at 541 million years ago.[3] In the 19th century, the boundary was set at time of appearance of the first abundant animal (metazoan) fossils but several hundred groups (taxa) of metazoa of the earlier Proterozoic era have been identified since the systematic study of those forms started in the 1950s. Most geologists and paleontologists would probably set the Proterozoic-Phanerozoic boundary either at the classic point where the first trilobites and reef-building animals (archaeocyatha) such as corals and others appear; at the first appearance of a complex feeding burrow called Treptichnus pedum; or at the first appearance of a group of small, generally disarticulated, armored forms termed 'the small shelly fauna'. The three different dividing points are within a few million years of each other.

In the older literature, the term Phanerozoic is generally used as a label for the time period of interest to paleontologists, but that use of the term seems to be falling into disuse in more modern literature.

3. Eras of the Phanerozoic

The Phanerozoic is divided into three eras: the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic, which are further subdivided into 12 periods. The Paleozoic features the rise of fish, amphibians and reptiles. The Mesozoic is ruled by the reptiles, and features the evolution of mammals, and more famously, dinosaurs, including birds. The Cenozoic is the time of the mammals, and more recently, humans.

3.1. Paleozoic Era

The Paleozoic is a time in Earth's history when complex life forms evolved, took their first breath of oxygen on dry land, and when the forerunners of all life on Earth began to diversify. There are six periods in the Paleozoic era: Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian.[4]

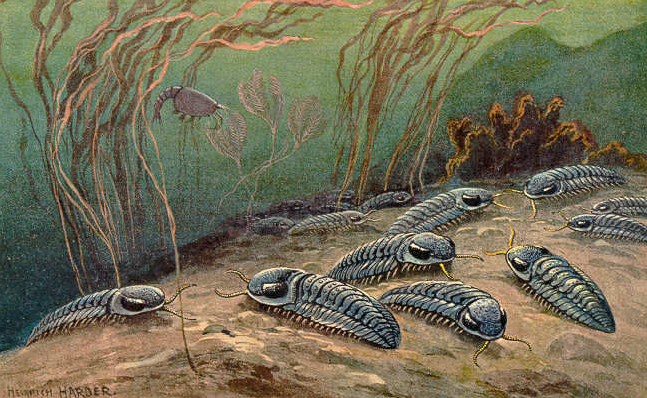

Cambrian Period

The Cambrian is the first period of the Paleozoic Era and ran from 541 to 485 million years ago. The Cambrian sparked a rapid expansion in evolution in an event known as the Cambrian explosion during which the greatest number of creatures evolved in a single period in the history of Earth. Plants like algae evolved, and the fauna was dominated by armored arthropods, such as trilobites. Almost all marine phyla evolved in this period. During this time, the super-continent Pannotia began to break up, most of which later recombined into the super-continent Gondwana.[5]

Ordovician Period

The Ordovician spans from 485 million years to 444 million years ago. The Ordovician was a time in Earth's history in which many species still prevalent today evolved, such as primitive fish, cephalopods, and coral. The most common forms of life, however, were trilobites, snails and shellfish. More importantly, the first arthropods crept ashore to colonize Gondwana, a continent empty of animal life. By the end of the Ordovician, Gondwana had moved from the equator to the South Pole, and Laurentia had collided with Baltica, closing the Iapetus Ocean. The glaciation of Gondwana resulted in a major drop in sea level, killing off all life that had established along its coast. Glaciation caused a snowball Earth, leading to the Ordovician–Silurian extinction, during which 60% of marine invertebrates and 25% of families became extinct. This is considered the first mass extinction and the second deadliest in the history of Earth.[6]

Silurian Period

The Silurian spans from 444 million years to 419 million years ago, which saw a warming from snowball Earth. This period saw the mass evolution of fish, as jawless fish became more numerous, jawed fish evolved, and the first freshwater fish evolved, though arthropods, such as sea scorpions, remained the apex predators. Fully terrestrial life evolved, which included early arachnids, fungi, and centipedes. The evolution of vascular plants (Cooksonia) allowed plants to gain a foothold on land. These early terrestrial plants are the forerunners of all plant life on land. During this time, there were four continents: Gondwana (Africa, South America, Australia, Antarctica, India), Laurentia (North America with parts of Europe), Baltica (the rest of Europe), and Siberia (Northern Asia). The recent rise in sea levels provided new habitats for many new species.[7]

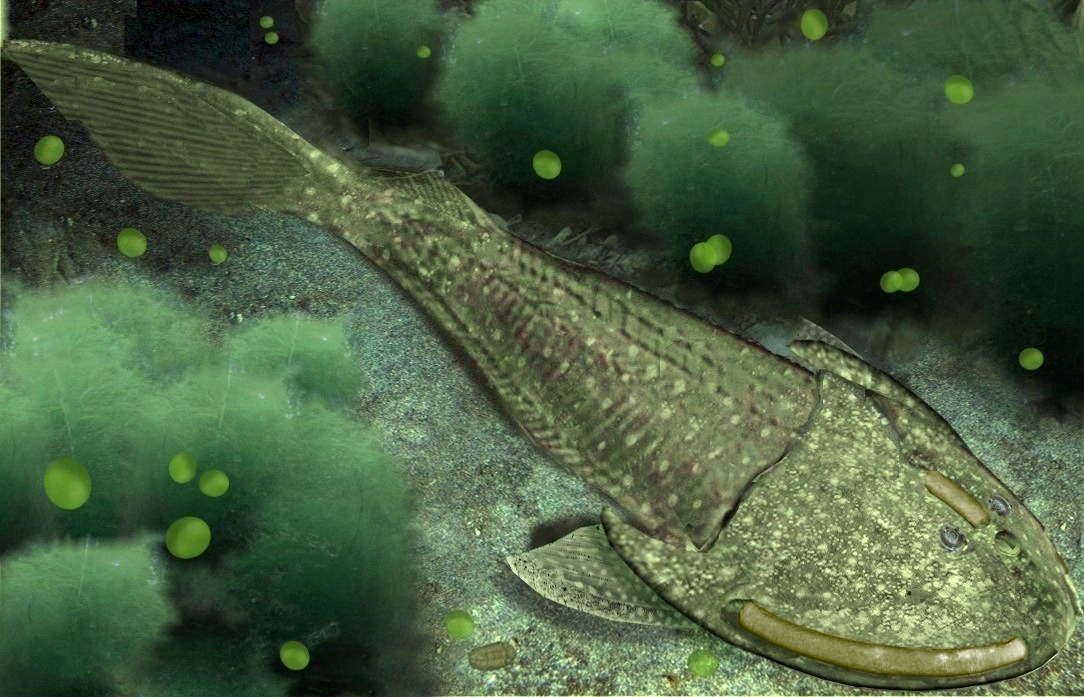

Devonian Period

The Devonian spans from 419 million years to 359 million years ago. Also informally known as the "Age of the Fish", the Devonian features a huge diversification in fish, including armored fish like Dunkleosteus and lobe-finned fish which eventually evolved into the first tetrapods. On land, plant groups diversified; the first trees and seeds evolved. By the Middle Devonian, shrub-like forests of primitive plants existed: lycophytes, horsetails, ferns, and progymnosperm. This event also allowed the diversification of arthropod life as they took advantage of the new habitat. The first amphibians also evolved, and the fish were now at the top of the food chain. Near the end of the Devonian, 70% of all species became extinct in an event known as the Late Devonian extinction, which is the second mass extinction known to have happened.[8]

Carboniferous Period

The Carboniferous spans from 359 million to 299 million years ago. During this period, average global temperatures were exceedingly high: the early Carboniferous averaged at about 20 degrees Celsius (but cooled to 10 degrees during the Middle Carboniferous).[9] Tropical swamps dominated the Earth, and the large amounts of trees created much of the carbon that became coal deposits (hence the name Carboniferous). The high oxygen levels caused by these swamps allowed massive arthropods, normally limited in size by their respiratory systems, to proliferate. Perhaps the most important evolutionary development of the time was the evolution of amniotic eggs, which allowed amphibians to move farther inland and remain the dominant vertebrates throughout the period. Also, the first reptiles and synapsids evolved in the swamps. Throughout the Carboniferous, there was a cooling pattern, which eventually led to the glaciation of Gondwana as much of it was situated around the south pole, in an event known as the Permo-Carboniferous glaciation or the Carboniferous rainforest collapse.[10]

Permian Period

The Permian spans from 299 million to 252 million years ago and was the last period of the Paleozoic era. At its beginning, all continents came together to form the super-continent Pangaea, surrounded by one ocean called Panthalassa. The Earth was very dry during this time, with harsh seasons, as the climate of the interior of Pangaea wasn't regulated by large bodies of water. Reptiles and synapsids flourished in the new dry climate. Creatures such as Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus ruled the new continent. The first conifers evolved, then dominated the terrestrial landscape. Nearing the end of the period, Scutosaurus and gorgonopsids filled the arid landmass. Eventually, they disappeared, along with 95% of all life on Earth in an event simply known as "the Great Dying", the world's third mass extinction event and the largest in its history.[11][12]

3.2. Mesozoic Era

The Mesozoic ranges from 252 million to 66 million years ago. Also known as "the age of the dinosaurs", the Mesozoic features the rise of reptiles on their 150-million-year conquest of the Earth on the land, in the seas, and in the air. There are three periods in the Mesozoic: Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous.

Triassic Period

The Triassic ranges from 252 million to 201 million years ago. The Triassic is a transitional time in Earth's history between the Permian Extinction and the lush Jurassic Period. It has three major epochs: Early Triassic, Middle Triassic and Late Triassic.[13]

The Early Triassic lasted between 252 million to 247 million years ago, and was dominated by deserts as Pangaea had not yet broken up, thus the interior was arid. The Earth had just witnessed a massive die-off in which 95% of all life became extinct. The most common life on Earth were Lystrosaurus, labyrinthodonts, and Euparkeria along with many other creatures that managed to survive the Great Dying. Temnospondyli flourished during this time and were dominant predators for much of the Triassic.[14]

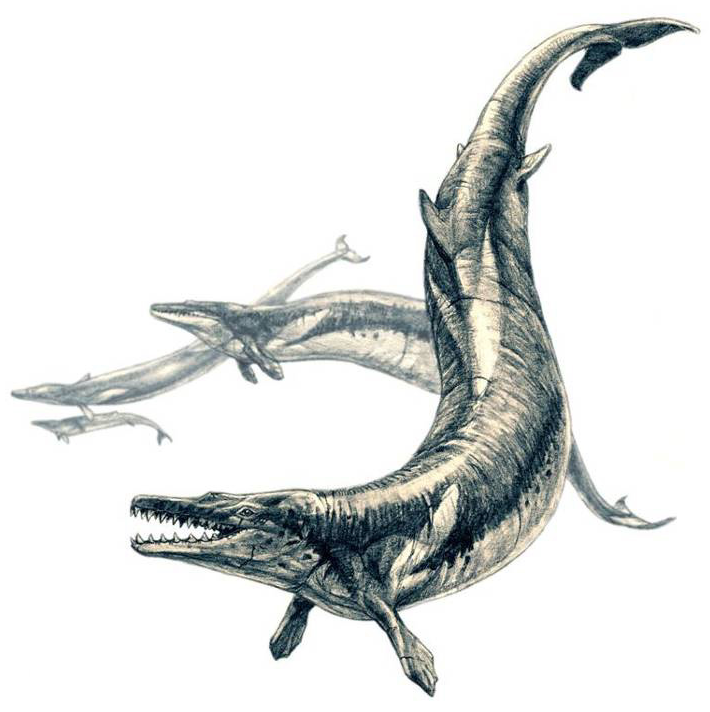

The Middle Triassic spans from 247 million to 237 million years ago. The Middle Triassic featured the beginnings of the breakup of Pangaea, and the beginning of the Tethys Sea. The ecosystem had recovered from the devastation of the Great Dying. Phytoplankton, coral, and crustaceans all had recovered, and the reptiles began increasing in size. New aquatic reptiles, such as ichthyosaurs and nothosaurs, proliferated in the seas. Meanwhile, on land, pine forests flourished, as well as mosquitoes and fruit flies. The first ancient crocodilians evolved, which sparked competition with the large amphibians that had long ruled the freshwater world.[15]

The Late Triassic spans from 237 million to 201 million years ago. Following the bloom of the Middle Triassic, the Late Triassic featured frequent rises of temperature, as well as moderate precipitation (10 to 20 inches per year). The recent warming led to a boom of reptilian evolution on land as the first true dinosaurs evolved, as well as pterosaurs. By the end of the period the first gigantic dinosaurs had evolved and advanced pterosaurs colonised Pangaea's deserts.[16][17] The climactic change, however, resulted in a large die-out known as the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, in which all archosaurs (excluding ancient crocodiles and dinosaurs), most synapsids, and almost all large amphibians became extinct, as well as 34% of marine life in the fourth mass extinction event. The extinction's cause is debated.[18][19]

Jurassic Period

The Jurassic ranges from 201 million to 145 million years ago, and features three major epochs: Early Jurassic, Middle Jurassic, and Late Jurassic.[20]

The Early Jurassic Epoch spans from 201 million to 174 million years ago.[20] The climate was much more humid than the Triassic, and as a result, the world was very tropical. In the oceans, plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and ammonites dominated the seas. On land, dinosaurs and other reptiles dominated the land, with species such as Dilophosaurus at the apex. The first true crocodiles evolved, pushing the large amphibians to near extinction. The reptiles rose to rule the world. Meanwhile, the first true mammals evolved, but never exceeded the height of a shrew.[21]

The Middle Jurassic Epoch spans from 174 million to 163 million years ago.[20] During this epoch, dinosaurs flourished as huge herds of sauropods, such as Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, filled the fern prairies of the Middle Jurassic. Many other predators rose as well, such as Allosaurus. Conifer forests made up a large portion of the world's forests. In the oceans, plesiosaurs were quite common, and ichthyosaurs were flourishing. This epoch was the peak of the reptiles.[22]

The Late Jurassic Epoch spans from 163 million to 145 million years ago.[20] The Late Jurassic featured a massive extinction of sauropods and ichthyosaurs due to the separation of Pangaea into Laurasia and Gondwana in an extinction known as the Jurassic-Cretaceous extinction. Sea levels rose, destroying fern prairies and creating shallows. Ichthyosaurs became extinct whereas sauropods, as a whole, did not; in fact, some species, like Titanosaurus, lived until the K–T extinction.[23] The increase in sea-levels opened up the Atlantic sea way which would continue to get larger over time. The divided world would give opportunity for the diversification of new dinosaurs.

Cretaceous Period

The Cretaceous is the Phanerozoic's longest period, and the last period of the Mesozoic. It spans from 145 million to 66 million years ago, and is divided into two epochs: Early Cretaceous, and Late Cretaceous.[24]

The Early Cretaceous Epoch spans from 145 million to 100 million years ago.[24] The Early Cretaceous saw the expansion of seaways, and as a result, the decline and extinction of sauropods (except in South America). Many coastal shallows were created, and that caused ichthyosaurs to die out. Mosasaurs evolved to replace them as apex species of the seas. Some island-hopping dinosaurs, like Eustreptospondylus, evolved to cope with the coastal shallows and small islands of ancient Europe. Other dinosaurs, such as Carcharodontosaurus and Spinosaurus, rose to fill the empty space that the Jurassic-Cretaceous extinction had created. Of the most successful would be the Iguanodon which spread to every continent. Seasons came back into effect and the poles grew seasonally colder. Dinosaurs such as the Leaellynasaura inhabited the polar forests year-round, while many dinosaurs, such as the Muttaburrasaurus, migrated there during summer . Since it was too cold for crocodiles, it was the last stronghold for large amphibians, such as the Koolasuchus. In this epoch Pterosaurs reached their maximum diversity and grew larger, as species like Tapejara and Ornithocheirus took to the skies. The first true birds evolved, possibly sparking competition between them and the pterosaurs.

The Late Cretaceous Epoch spans from 100 million to 66 million years ago.[24] The Late Cretaceous featured a cooling trend that would continue into the Cenozoic Era. Eventually, tropical ecology was restricted to the equator and areas beyond the tropic lines featured extreme seasonal changes of weather. Dinosaurs still thrived as new species such as Tyrannosaurus, Ankylosaurus, Triceratops and Hadrosaurs dominated the food web. Whether or not Pterosaurs went into a decline as birds radiated is debated; however, many families survived until the end of the Cretaceous, alongside new species such as the gigantic Quetzalcoatlus.[25] Marsupials evolved within the large conifer forests as scavengers. In the oceans, Mosasaurs ruled the seas to fill the role of the ichthyosaurs, and huge plesiosaurs, such as Elasmosaurus, evolved. Also, the first flowering plants evolved. At the end of the Cretaceous, the Deccan Traps and other volcanic eruptions were poisoning the atmosphere. As this was continued, it is thought that a large meteor smashed into Earth, creating the Chicxulub Crater creating the event known as the K–T extinction, the fifth and most recent mass extinction event, during which 75% of life on Earth became extinct, including all non-avian dinosaurs. Every living thing with a body mass over 10 kilograms became extinct, and the age of the dinosaurs came to an end.[26][27]

3.3. Cenozoic Era

The Cenozoic featured the rise of mammals as the dominant class of animals, as the end of the age of the dinosaurs left significant evolutionary vacuums. There are three divisions of the Cenozoic: Paleogene, Neogene and Quaternary.

Paleogene Period

The Paleogene spans from the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, some 66 million years ago, to the dawn of the Neogene 23 million years ago. It features three epochs: Paleocene, Eocene and Oligocene.

The Paleocene Epoch began with the K–T extinction event caused by the impact of a meteorite in the area of present-day Yucatan Peninsula and caused the destruction of 75% of all species on Earth. The Early Paleocene saw the recovery of the Earth from that event. The continents began to take their modern shape, but all continents (and India) were separated from each other. Afro-Eurasia was separated by the Tethys Sea, and the Americas were separated by the strait of Panama, as the Isthmus of Panama had not yet formed. This epoch featured a general warming trend, and jungles eventually reached the poles. The oceans were dominated by sharks as the large reptiles that had once ruled became extinct. Archaic mammals, such as creodonts and early primates that evolved during the Mesozoic filled the world. Mammals were still quite small, meanwhile enormous crocodiles and snakes like Titanoboa radiated to fill the niche of top predator.

The Eocene Epoch ranged from 56 million to 34 million years ago. In the early Eocene, most land mammals were small and living in cramped jungles, much like the Paleocene. Among them were early primates, whales and horses along with many other early forms of mammals. At the top of the food chains were huge birds, such as Gastornis. Carnivorous flightless birds continued to be top predators for much of the rest of the Cenozoic, until their extinction in the Quaternary period. The temperature was 30 degrees Celsius with little temperature gradient from pole to pole. In the Middle Eocene Epoch, the circum-Antarctic current between Australia and Antarctica formed which disrupted ocean currents worldwide, resulting in global cooling, and caused the jungles to shrink. This allowed mammals to grow; some such as whales to mammoth proportions, which were, by now, almost fully aquatic. Mammals like Andrewsarchus were now at the top of the food-chain and sharks were replaced by Basilosaurus, whales, as rulers of the seas. The late Eocene Epoch saw the rebirth of seasons, which caused the expansion of savanna-like areas, along with the evolution of grass.[28][29] At the transition between the Eocene and Oligocene epochs there was a significant extinction event, the cause of which is debated.

The Oligocene Epoch spans from 34 million to 23 million years ago. The Oligocene was an important transitional period between the tropical world of the Eocene and more modern ecosystems. This period featured a global expansion of grass which had led to many new species to take advantage, including the first elephants, cats, dogs, marsupials and many other species still prevalent today. Many other species of plants evolved during this epoch also, such as the evergreen trees. The long term cooling continued and seasonal rains patterns established. Mammals continued to grow larger. Paraceratherium, the largest land mammal to ever live evolved during this epoch, along with many other perissodactyls.

Neogene Period

The Neogene spans from 23.03 million to 2.58 million years ago. It features 2 epochs: the Miocene, and the Pliocene.[30]

The Miocene spans from 23.03 to 5.333 million years ago and is a period in which grass spread further across, effectively dominating a large portion of the world, diminishing forests in the process. Kelp forests evolved, leading to the evolution of new species, such as sea otters. During this time, perissodactyla thrived, and evolved into many different varieties. Alongside them were the apes, which evolved into 30 species. Overall, arid and mountainous land dominated most of the world, as did grazers. The Tethys Sea finally closed with the creation of the Arabian Peninsula and in its wake left the Black, Red, Mediterranean and Caspian Seas. This only increased aridity. Many new plants evolved, and 95% of modern seed plants evolved in the mid-Miocene.[31]

The Pliocene lasted from 5.333 to 2.58 million years ago. The Pliocene featured dramatic climactic changes, which ultimately led to modern species and plants. The Mediterranean Sea dried up for several thousand years in the Messinian salinity crisis. Along with these major geological events, Australopithecus evolved in Africa, beginning the human branch. The isthmus of Panama formed, and animals migrated between North and South America, wreaking havoc on the local ecology. Climatic changes brought savannas that are still continuing to spread across the world, Indian monsoons, deserts in East Asia, and the beginnings of the Sahara desert. The Earth's continents and seas moved into their present shapes. The world map has not changed much since, save for changes brought about by the glaciations of the Quaternary, such as the Great Lakes.[32][33]

Quaternary Period

The Quaternary spans from 2.58 million years ago to present day, and is the shortest geological period in the Phanerozoic Eon. It features modern animals, and dramatic changes in the climate. It is divided into two epochs: the Pleistocene and the Holocene.

The Pleistocene lasted from 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago. This epoch was marked by ice ages as a result of the cooling trend that started in the Mid-Eocene. There were at least four separate glaciation periods marked by the advance of ice caps as far south as 40 degrees N latitude in mountainous areas. Meanwhile, Africa experienced a trend of desiccation which resulted in the creation of the Sahara, Namib, and Kalahari deserts. Many animals evolved including mammoths, giant ground sloths, dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, and most famously Homo sapiens. One hundred thousand years ago marked the end of one of the worst droughts of Africa, and led to the expansion of primitive human. As the Pleistocene drew to a close, a major extinction wiped out much of the world's megafauna, including some of the hominid species, such as Neanderthals. All the continents were affected, but Africa to a lesser extent. That continent retains many large animals, such as hippos. The extent to which Homo Sapiens were involved in this extinction is debated.[34]

The Holocene began 11,700 years ago and lasts until the present day. All recorded history and "the Human history" lies within the boundaries of the Holocene epoch.[35] Human activity is blamed for a mass extinction that began roughly 10,000 years ago, though the species becoming extinct have only been recorded since the Industrial Revolution. This is sometimes referred to as the "Sixth Extinction". More than 322 species have become extinct due to human activity since the Industrial Revolution.[36][37]

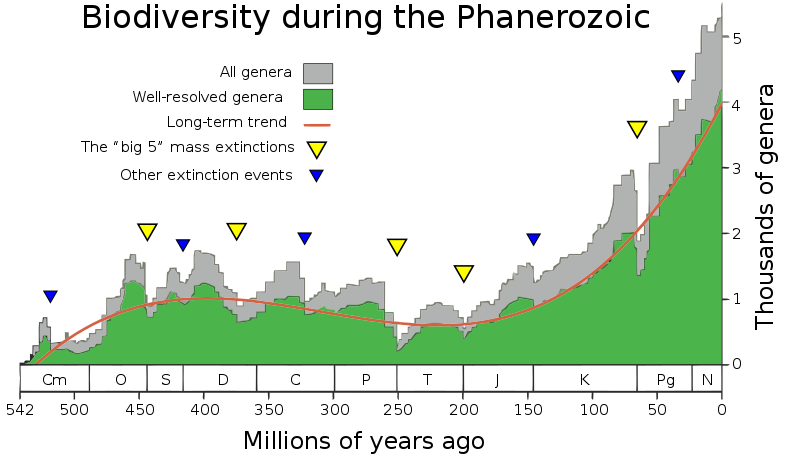

4. Biodiversity

It has been demonstrated that changes in biodiversity through the Phanerozoic correlate much better with the hyperbolic model (widely used in demography and macrosociology) than with exponential and logistic models (traditionally used in population biology and extensively applied to fossil biodiversity as well). The latter models imply that changes in diversity are guided by a first-order positive feedback (more ancestors, more descendants) or a negative feedback that arises from resource limitation, or both. The hyperbolic model implies a second-order positive feedback. The hyperbolic pattern of the human population growth arises from a second-order positive feedback, caused by the interaction of the population size and the rate of technological growth.[38] The character of biodiversity growth in the Phanerozoic Eon can be similarly accounted for by a feedback between the diversity and community structure complexity. It is suggested that the similarity between the curves of biodiversity and human population probably comes from the fact that both are derived from the superposition on the hyperbolic trend of cyclical and random dynamics.[38]

References

- Chadwick, G.H. (1930). "Subdivision of geologic time". Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 41: 47–48.

- Harland, B., ed (1990). A geologic timescale 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-521-38361-7. https://archive.org/details/geologictimescal00camb/page/30.

- "Phanerozoic Eon | geochronology" (in en). Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. https://web.archive.org/web/20180317234516/https://www.britannica.com/science/Phanerozoic-Eon.

- University of California. "Paleozoic". University of California. Archived from the original on 2015-05-02. https://web.archive.org/web/20150502123522/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/paleozoic/paleozoic.php.

- University of California. "Cambrian". University of California. Archived from the original on 2012-05-15. https://web.archive.org/web/20120515190500/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cambrian/cambrian.php.

- University of California. "Ordovician". University of California. Archived from the original on 2015-05-02. https://web.archive.org/web/20150502201732/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/ordovician/ordovician.php.

- University of California. "Silurian". University of California. Archived from the original on 2017-06-16. https://web.archive.org/web/20170616141804/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/silurian/silurian.php.

- University of California. "Devonian". University of California. Archived from the original on 2012-05-11. https://web.archive.org/web/20120511155551/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/devonian/devonian.php.

- Monte Hieb. "Carboniferous Era". unknown. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. https://web.archive.org/web/20141220004649/http://www.geocraft.com/WVFossils/Carboniferous_climate.html.

- University of California. "Carboniferous". University of California. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. https://web.archive.org/web/20120210070913/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/carboniferous/carboniferous.php.

- Natural History Museum. "The Great Dying". Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. https://web.archive.org/web/20150420192109/http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/life/dinosaurs-other-extinct-creatures/mass-extinctions/end-permian-mass-extinction/.

- University of California. "Permian Era". University of California. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. https://web.archive.org/web/20170704140229/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/permian/permian.php.

- Alan Logan. "Triassic". University of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on 2015-04-26. https://web.archive.org/web/20150426165804/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/604667/Triassic-Period/225842/Economic-significance-of-Triassic-deposits.

- Alan Kazlev. "Early Triassic". unknown. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. https://web.archive.org/web/20150427233440/http://palaeos.com/mesozoic/triassic/earlytrias.htm.

- Rubidge. "Middle Triassic". unknown. Archived from the original on 2015-04-29. https://web.archive.org/web/20150429191835/http://palaeos.com/mesozoic/triassic/midtrias.html.

- "Giant bones get archaeologists rethinking Triassic dinosaurs" (in en). The National. https://www.thenational.ae/world/the-americas/giant-bones-get-archaeologists-rethinking-triassic-dinosaurs-1.748676.

- Britt, Brooks B.; Dalla Vecchia, Fabio M.; Chure, Daniel J.; Engelmann, George F.; Whiting, Michael F.; Scheetz, Rodney D. (2018-08-13). "Caelestiventus hanseni gen. et sp. nov. extends the desert-dwelling pterosaur record back 65 million years" (in En). Nature Ecology & Evolution 2 (9): 1386–1392. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0627-y. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 30104753. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fs41559-018-0627-y

- Graham Ryder; David Fastovsky; Stefan Gartner (1996-01-01). Late Triassic Extinction. ISBN 9780813723075. https://books.google.com/books?id=kAup0TOL09gC&pg=PA19#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Enchanted Learning. "Late Triassic life". Enchanted Learning. Archived from the original on 2015-02-28. https://web.archive.org/web/20150228065410/http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/dinosaurs/mesozoic/triassic/lt.shtml.

- Carol Marie Tang. "Jurassic Era". California Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 2015-05-06. https://web.archive.org/web/20150506035157/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/308541/Jurassic-Period/257903/Major-subdivisions-of-the-Jurassic-System.

- Alan Kazlev. "Early Jurassic". unknown. Archived from the original on 2015-06-01. https://web.archive.org/web/20150601013323/http://palaeos.com/mesozoic/jurassic/earlyjura.html.

- Enchanted Learning. "Middle Jurassic". Enchanted Learning. Archived from the original on 2015-02-28. https://web.archive.org/web/20150228092248/http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/dinosaurs/mesozoic/jurassic/mj.shtml.

- Bob Strauss. "Cretaceous sauropods". author. Archived from the original on 2015-03-19. https://web.archive.org/web/20150319105452/http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/typesofdinosaurs/a/titanosaurs.htm.

- Carl Fred Koch. "Cretaceous". Old Dominion University. Archived from the original on 2015-05-14. https://web.archive.org/web/20150514211348/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/142729/Cretaceous-Period/257709/Major-subdivisions-of-the-Cretaceous-System.

- "Pterosaurs More Diverse at the End of the Cretaceous than Previously Thought" (in en-US). Everything Dinosaur Blog. https://blog.everythingdinosaur.co.uk/blog/_archives/2018/03/15/pterosaurs-more-diverse-at-the-end-of-the-cretaceous-than-previously-thought.html.

- University of California. "Cretaceous". University of California. Archived from the original on 2017-06-11. https://web.archive.org/web/20170611021416/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/mesozoic/cretaceous/cretaceous.php.

- Elizabeth Howell. "K-T Extinction event". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 2015-05-05. https://web.archive.org/web/20150505160632/http://www.universetoday.com/36697/the-asteroid-that-killed-the-dinosaurs/.

- University of California. "Eocene Climate". University of California. Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. https://web.archive.org/web/20150420031850/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/tertiary/eocene.php.

- National Geographic Society. "Eocene". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2015-05-08. https://web.archive.org/web/20150508115651/http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/prehistoric-world/paleogene.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Neogene". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2015-05-02. https://web.archive.org/web/20150502193553/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/408872/Neogene-Period.

- University of California. "Miocene". University of California. Archived from the original on 2015-05-04. https://web.archive.org/web/20150504035928/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/tertiary/miocene.php.

- University of California. "Pliocene". University of California. Archived from the original on 2015-04-29. https://web.archive.org/web/20150429052833/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/tertiary/pliocene.php.

- Jonathan Adams. "Pliocene climate". Oak Ridge National Library. Archived from the original on 2015-02-25. https://web.archive.org/web/20150225011508/http://www.esd.ornl.gov/projects/qen/pliocene.html.

- University of California. "Pleistocene". University of California. Archived from the original on 2014-08-24. https://web.archive.org/web/20140824111711/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/quaternary/pleistocene.php.

- University of California. "Holocene". University of California. Archived from the original on 2015-05-02. https://web.archive.org/web/20150502160331/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/quaternary/holocene.php.

- Scientific American. "Sixth Extinction extinctions". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2014-07-27. https://web.archive.org/web/20140727234806/http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/fact-or-fiction-the-sixth-mass-extinction-can-be-stopped/.

- IUCN. "Sixth Extinction". IUCN. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. https://web.archive.org/web/20120729102308/http://iucn.org/?4143%2FExtinction-crisis-continues-apace.

- See, e. g., Markov, A.; Korotayev, A. (2008). "Hyperbolic growth of marine and continental biodiversity through the Phanerozoic and community evolution". Zhurnal Obshchei Biologii (Journal of General Biology) 69 (3): 175–194. Archived from the original on 2009-12-25. https://web.archive.org/web/20091225000305/http://elementy.ru/genbio/abstracts?artid=177.