| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beatrix Zheng | -- | 2650 | 2022-09-27 02:50:38 |

Video Upload Options

Philippine Hokkien (Chinese: 咱儂話; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lán-lâng-ōe; literally: 'our people's language'), is the variant of Hokkien as spoken by about 98.7% of the ethnic Chinese population of the Philippines. A mixed version that involves this language with Tagalog and English is Hokaglish.

1. Terminology

The term Philippine Hokkien is used when differentiating the variety of Hokkien spoken in the Philippines from those spoken in Taiwan, China, and other Southeast Asian countries. There are various terms that native to the speaker itself used:

- 咱儂話 (Hokkien: lán-lâng-ōe [lán-lâng-uē]; Mandarin: zánrénhuà) -- literally means "our own people's speech", it mostly refers to Philippine Hokkien.

- 閩南語 (Hokkien: bân-lâm-gí; Mandarin: mǐnnányǔ) -- literally means "Southern Min language" or "Ban Lam Gi" or "Minnan language", this refers to the variant spoken in Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Xiamen and Taiwan (in Taiwan and Mainland China).

- 台語 (Hokkien: tâi-gí; Mandarin: tái-yǔ) and 台灣話 (Hokkien: tâi-oân-ōe [tâi-uân-uē]; Mandarin: táiwanhuà) -- literally means "Taiwanese language", this refers to Taiwanese Hokkien.

- 厦門話 (Hokkien: ē-mn̂g-ōe [ē-mn̂g-uē]; Mandarin: xiamenhua)--literally means Xiamen Speech refers to Min Nan spoken in Xiamen City in Fujian, Mainland China.

- 泉州話 (Hokkien: choân-chiu-ōe [tsuân-chiu-uē] ; Mandarin: quánzhōuhuà)--literally means Quanzhou Speech refers to Min Nan spoken in Quanzhou City and other City Like Shishi City, Nan-an City,An-xi City Jinjiang City, Hui-an City, Ying-chun City, Dehua City and Tong-an City in Fujian, Mainland China.

- 漳州話 (Hokkien: chiang-chiu-ōe [tsiang-chiu-uē]; Mandarin: zhāngzhōuhuà)--literally means Zhangzhou Speech refers to Min Nan spoken in Zhangzhou City and other City Like Longyan City, Zhangping City, and Dongshan City in Fujian, Mainland China.

- 福建話 (Hokkien: hok-kiàn-ōe [hok-kiàn-uē]; Mandarin: fújiànhuà) -- literally means "Fujianese language", this refers to all Fujianese varieties in Taiwan and Mainland China, however this term is a misnomer because in Fujian, China there are many other languages like Min Dong and Min Zhong.

In the Philippines, all terms are used interchangeably to refer to Philippine Hokkien.

2. Classification

Philippine Hokkien is generally similar to the Hokkien dialect spoken in Jinjiang and Quanzhou, however, the Hokkien dialect spoken in Xiamen, also known as Amoy (Chinese: 廈門話), is considered the standard and prestigious form of Hokkien. Minor differences with other Hokkien dialects in Taiwan, China, or throughout Southeast Asia only occur in terms of vocabulary.

3. Geographic Spread

Hokkien is spoken by ethnic Chinese throughout the Philippines . Major metropolitan areas that have a significant number of Chinese include Metro Manila, Metro Cebu and Metro Davao. Other cities which also substantial Chinese populations in Angeles City, Bacolod City, Cagayan de Oro, Dagupan City, Dumaguete City, Ilagan, Iloilo City, Legaspi, Naga City, Tacloban City, Vigan and Zamboanga City.

Provinces with a large Chinese population include Albay, Bataan, Batangas, Bohol, Cagayan, Camarines Sur, Cavite, Cebu, Compostela Valley, Davao, Davao del Sur, Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur, Iloilo, Isabela, Laguna, La Union, Leyte, Misamis Occidental and Misamis Oriental, Negros Occidental and Negros Oriental, Palawan, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Quezon, Rizal, South Cotabato, Surigao del Norte, Tarlac and Zamboanga del Sur.

4. Sociolinguistics

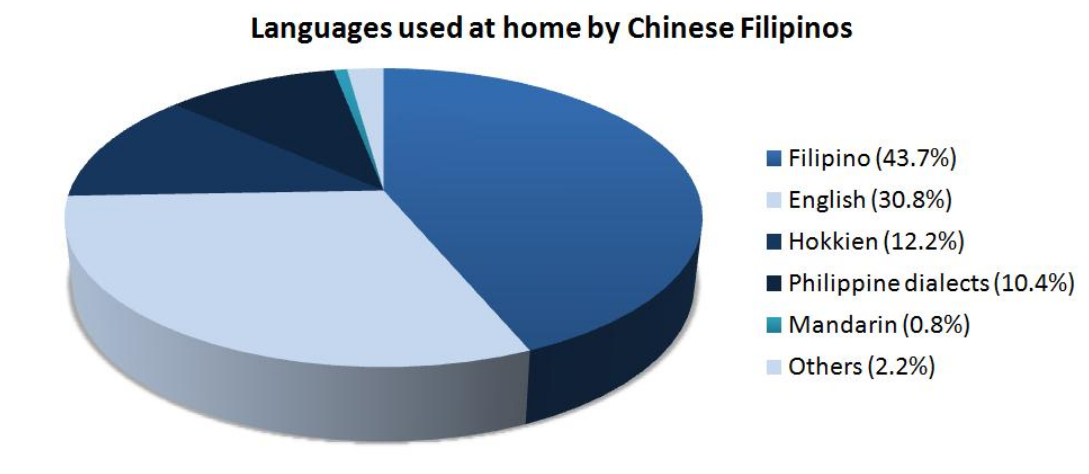

Only 12.2% of all ethnic Chinese have a varieties of Chinese as their mother tongue. Nevertheless, the vast majority (77%) still retain the ability to understand and speak Hokkien as a second or third language.[1]

Prior to the emergence of China as a regional power in the late 1990s, speaking Hokkien, Mandarin, Cantonese and other Chinese varieties was seen as old-fashioned and awkward, with the younger generation of Chinese Filipinos opting to use either English, Filipino or various other regional languages as their first languages.

Recent developments showing the rise of a politically and economically stronger China eventually led to the newly found elegance and style now associated with speaking Hokkien and other Chinese varieties. Hence, there is a stronger clamour for instructors who can produce students fluent in Hokkien and Mandarin. Many young parents are also shifting to using Hokkien at home as their children's first language.

5. Education

Around 120 Chinese Filipino educational institutions exist throughout the Philippines, with the vast majority being concentrated in Metro Manila. These schools primarily differ from others in the Philippines with the presence of Chinese-language subjects.

These schools were previously under direct supervision of the Republic of China (Taiwan) Ministry of Education until 1976 when Presidential Decree 176 of 1973 (sometimes called the "Filipinization" decree) of former President Ferdinand Marcos placed all foreign schools under the authority of the Department of Education. The decree effectively halved the time allotted for Chinese subjects, while Tagalog became a required subject, and the medium of instruction shifted from Mandarin Chinese to English.

5.1. Curriculum

Chinese Filipino primary and secondary schools typically feature Chinese subjects added to the standard curriculum prescribed by the Department of Education. The three core Chinese subjects are Chinese Grammar (Chinese: 華語; pinyin: huáyǔ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: hoâ-gí; literally: 'Mandarin'), Chinese Composition (Chinese: 綜合; pinyin: zònghé; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: chong-ha̍p), and Chinese Mathematics (Chinese: 數學; pinyin: shùxué; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: sò͘-ha̍k). Other schools may offer additional subjects such as Chinese calligraphy (Chinese: 毛筆; pinyin: máobǐ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: mô͘-pit), history, geography, and culture, all integrated in all the three core Chinese subjects in accordance with PD № 176. All Chinese subjects are taught in Mandarin Chinese, and in some schools, students are prohibited from speaking English, Filipino, or even Hokkien during these classes.

Presently, the Ateneo de Manila University, under their Chinese Studies Programme offers Hokkien 1 (Chn 8) and Hokkien 2 (Chn 9) as electives.[2]

On the other hand, Chiang Kai Shek College offers Fookien Classes in their CKS College Language Center.[3]

6. History and Formation

Philippine Hokkien developed during successive centuries of the Chinese Filipinos being in the Philippines.

Starting from the early 19th century, Chinese migrants from Fujian province, specifically from Quanzhou eventually eclipsed those from Guangdong province, establishing Hokkien as the primary variety of Chinese spoken in the Philippines.

As ethnic Chinese began to associate with Filipinos and learn Tagalog and English, they began to use native terms used to refer to items that are found only in the Philippine milieu. Also, since most Chinese migrants from Fujian are businessmen and merchants, many have been using colloquialisms and slang words, rather than grammatically correct scholarly jargon. Both result to the current preponderance of English, Tagalog, and Fujian colloquialisms in Philippine Hokkien.

7. Orthography

In some situations, Philippine Hokkien is written in the Latin alphabet. The Chinese Congress on World Evangelization –Philippines, an international organization of Overseas Chinese Christian churches, use a romanization system based predominantly on the Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ) system. The origins of this system and its extensive use in the Christian community have led to it being known by some modern writers as "Church Romanization" (Kàu-hōe Lô-má-jī; 教會羅馬字); often abbreviated to Kàu-lô (教羅). There is some debate on whether "Pe̍h-ōe-jī" or "Church Romanization" is the more appropriate name. During the 19th century, Pe̍h-ōe-jī was used extensively in Chinese Filipino churches and as a result, many Chinese Filipinos were literate in this system. Since 2006, the Taiwanese Romanization System also known as "Tâi-lô", which is derived from Pe̍h-ōe-jī has been officially promoted by Taiwan's Ministry of Education. Due to the extensive Taiwanese influence on Chinese education in the Philippines such as the use of Taiwanese textbooks and materials which contain traditional Chinese characters, Chinese Filipinos and ethnic Filipinos alike who formally study the language nowadays may use a version of Tâi-lô.

8. Phonology

8.1. Initials

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | ||

| Nasal | m [m] ㄇ 名 (miâ) |

n [n] ㄋ 耐 (nāi) |

ng [ŋ] ㄫ 硬 (ngǐ) |

|||||||

| Plosive | Unaspirated | p [p] ㄅ 邊 (pian) |

b [b] ㆠ 文 (bûn) |

t [t] ㄉ 地 (tē) |

d [d] |

k [k] ㄍ 求 (kiû) |

g [g] ㆣ 牛 (gû) |

ʔ [ʔ] 音 (im) |

||

| Aspirated | ph [pʰ] ㄆ 波 (pho) |

th [tʰ] ㄊ 他 (thaⁿ) |

kh [kʰ] ㄎ 去 (khì) |

|||||||

| Affricate | Unaspirated | ch [ts] ㄗ 曾 (chan) |

j [dz] ㆡ 熱 (joa̍h [jua̍h]) |

chi [tɕ] ㄐ 祝 (chiok) |

ji [dʑ] ㆢ 入 (ji̍p) |

|||||

| Aspirated | chh [tsʰ] ㄘ 出 (chhut) |

chhi [tɕʰ] ㄑ 手 (chhiú) |

||||||||

| Fricative | s [s] ㄙ 衫 (saⁿ) |

si [ɕ] ㄒ 心 (sim) |

h [h] ㄏ 火 (hé) |

|||||||

| Lateral | l [l] ㄌ 柳 (liú) |

|||||||||

8.2. Vowels

[5]

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

8.3. Code Endings

|

|

8.4. Tones

| Tones | 平 | 上 | 去 | 入 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 陰平 | 陽平 | 陰上 | 陽上 | 陰去 | 陽去 | 陰入 | 陽入 | ||

| Tone Number | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 8 | |

| 調值 | Xiamen, Fujian | 44 | 24 | 53 | - | 21 | 22 | 32 | 4 |

| - | |||||||||

| Taipei, Taiwan | 44 | 24 | 53 | - | 11 | 33 | 32 | 4 | |

| - | |||||||||

| Tainan, Taiwan | 44 | 23 | 41 | - | 21 | 33 | 32 | 44 | |

| - | |||||||||

| Zhangzhou, Fujian | 34 | 13 | 53 | - | 21 | 22 | 32 | 121 | |

| - | |||||||||

| Quanzhou, Fujian Manila, Philippines |

33 | 24 | 554 | 22 | 41 | 5 | 24 | ||

| 東 taŋ1 | 銅 taŋ5 | 董 taŋ2 | 重 taŋ6 | 凍 taŋ3 | 動 taŋ7 | 觸 tak4 | 逐 tak8 | ||

In general, Min Nan has 7 to 9 tones, and tone sandhi is extensive. There are minor variations between the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou tone systems. Taiwanese tones follow the schemes of Amoy or Quanzhou, depending on the area of Taiwan. Both Amoy and Taiwanese Min Nan typically has 7 tones; the 9th tone is used only in special or foreign loan words. Quanzhou is the only Min Nan dialect with 8 tones, of which the 6th tone is present. The Philippine Min Nan dialect follows the 8 tones and tone sandhi of Quanzhou because many of the Chinese Filipino who speak Min Nan in the Philippines have ancestors from Quanzhou (Fujian) in China .

9. Differences from Other Hokkien Variants

Philippine Hokkien is largely derived from the Hokkien dialect spoken in Quanzhou. However, it gradually absorbed influences from both Standard Amoy and Zhangzhou variants.

Although Philippine Hokkien is generally mutually comprehensible with any Hokkien variant, including Taiwanese Hokkien, the numerous English and Filipino loanwords as well as the extensive use of colloquialisms (even those which are now unused in China) can result in confusion among Hokkien speakers from outside of the Philippines. In Cebu and Dumaguete for example, instead of Tagalog, Cebuano words are incorporated. In Iloilo and Bacolod, Hiligaynon words are incorporated. While in Central Luzon, Kapampangan and Pangasinan words are incorporated.

9.1. Similarities With Either Quanzhou and Zhangzhou Variants

Most speakers of Philippine Hokkien have their origins in Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, hence the influence of the Hokkien variants spoken in these areas.

- The use of -iak suffix where other variants have -ek [-ik], e.g. 色 siak or sek [sik], 綠色 lia̍k-siak or lia̍k-sek [lia̍k-sik], etc.

- The use of -i suffix where other variants have -u, e.g. 語 gí/gú, 做菜 chí/chú [tsí/tsú], etc.

- The use of -uiⁿ [-uinn] suffix where other variants have -eng [-ing] or -oaiⁿ [-uainn], e.g. 最先 suiⁿ [suinn], 高 kûiⁿ [kûinn], etc.

- The use of -oang [-uang] suffix where other variants have -ong, e.g. 風 hoang [huang], etc.

9.2. Similarities With Standard Xiamen (Amoy) Variant

Since the Standard Xiamen (Amoy) variant is considered the most prestigious variant of Hokkien and is the spoken variant of the educated residents of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, elements of this variant occasionally seep into Philippine Hokkien, such as the following:

- The use of -ng suffix where other variants have -uiⁿ [-uinn], e.g. 門 mng, 飯 png, 酸 sng, etc.

- The use of -e suffix where other variants have -oe, e.g. 火 he, 未 be, 地 tē, 細 sè.

- The use of -oe [-ue] suffix where other variants have -oa [-ua], e.g. 話 ōe [ūe], 花 hoe [hue], 瓜 koe [kue].

- The use of -iuⁿ [-iunn] suffix where other variants have -iauⁿ [iaunn]), e.g. 羊 iûⁿ [iûnn], 丈 tiūⁿ [tiūnn], 想 siuⁿ [siunn].

- The use of -iong suffix where other variants have -iang, e.g. 上 siāng, 香 hiang.

9.3. Use of Colloquialisms

Philippine Hokkien (as well as Southeast Asian Hokkien) uses a disproportionately large amount of colloquial words as compared to the Hokkien variants used in China and Taiwan. Many of the colloquialisms are themselves considered dated (specifically, pre-World War II) in China but are still in use among Hokkien-speaking Chinese Filipinos.

- am-cham [am-tsam] (骯髒): dirty. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "lāu-siông".

- chha-thâu [tshia-thâu] (車頭): chauffeur (literally, "car head", but used in China to refer to a headstock). Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "chhia-hu [tshia-hu]" (車夫).

- chhiáⁿ-thâu-lō͘ [tshiánn-thâu-lōo] (請頭路): to work, to get employed. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "chòe-kang [tsuè-kang]" (揣工).

- chhiú-siak [tshiú-siak] (首饰): jewelry. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "chu-pó [tsu-pó]" (珠寶).

- khan-chhiú [khan-tshiú] (牽手): to marry. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "kiat-hun" (結婚).

- liām-chúi [liām-tsúi](淋水): to baptise. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "sóe-lé [sué-lé]" (洗禮).

- pēⁿ-chhù/pīⁿ-chhù [pēnn-tshù/pīnn-tshù] (病厝): hospital (literally, "sick house"). Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "i-ìⁿ [i-ìnn]" (醫院).

- pēⁿ-īⁿ/pīⁿ-īⁿ [pēnn-īnn/pīnn-īnn] (病院): hospital (literally, "sick house"). Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "i-ìⁿ [i-ìnn]" (醫院).

- sio̍k (俗): cheap, economical. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "piān-gî" (便宜).

- siong-hó (相好): friend (literally, "good acquaintance"). Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "pêng-iú [pîng-iú]" (朋友).

- Tn̂g-soaⁿ [Tn̂g-suann] (唐山): China, derived from the term Tangshan. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "Tiong-kok" (中國).

- tōa-o̍h [tuā-o̍h] (大學): university or college. Also found in Penang Hokkien. Its equivalent in the Standard Xiamen dialect is "tāi-ha̍k" (大學).

9.4. Loanwords from English, Spanish, Portuguese and Philippine Languages

Philippine Hokkien, like other Southeast Asian variants of Hokkien (e.g. Singaporean Hokkien, Penang Hokkien, Johor Hokkien and Medan Hokkien) absorbed several indigenous and English words and phrases which are usually only found (or are more important) in its new milieu. These "borrowed" words are never used in written Hokkien, for which Mandarin characters are used.

- ba-su: cup

- chhe-ke [tshe-ke]: check

- ka-mú-ti: sweet potato

- o-pi-sin: office

- pan-sit: stir-fried noodles in Chinese Filipino cuisine

- sap-bûn (雪文): soap (though this sounds similar to the Tagalog sabón, is not borrowed from that language. In Taiwanese, which is a variant of Hokkien that is not influenced by Tagalog, it is pronounced as sap-bûn. Etymologically speaking, perhaps both Taiwanese and Tagalog ultimately derive sap-bûn/sabon from the Romance languages that had brought the concept of soap to them, such as Portuguese sabão and Spanish jabón respectively).

10. Sample Phrases

- Everyday Phrases

- good morning - hó-chá-khí [hó-tsá-khí] (好早起)

- good afternoon - hó-ē-po͘ [hó-ē-poo] (好下埔)

- good evening - hó-àm-mî (好暗暝)

- How are you? - Dí-hó--bô? (你好無?)

- Fine, thank you. - hó, to-siā. (好,多謝。)

- And you? - Dí-nì? (你呢?)

- you're welcome - m-bián kheh-khì (毋免客氣)

- sorry - tùi-put-chū [tùi-put-tsū] (對不住)

- Congratulations! - Kiong-hí! (恭喜!)

- My surname is Tsua/Tsai/Tsai/Kai. - Góa sìⁿ Chhòa. [Gúa sìnn Tshuà.] (我姓蔡。)

- I do not know - Goá m̄ chai-iáⁿ. [Gúa m̄ tsai-iann.] (我毋知影。)

- Do you speak Philippine Hokkien? - Dí ē-hiáu kóng Lán-lâng-ōe mâ? [Dí ē-hiáu kóng Lán-lâng-uē mâ?] (你會曉講咱儂話嗎?)

- Common Pronouns

- this - che [tse] (這, 即), chit-ê [tsit-ê] (這個, 即個)

- that - he (許, 彼), hit-ê (彼個)

- here - chia [tsia] (者), hia/hiâ (遮, 遐), chit-tau [tsit-tau] (這兜)

- there - hia (許, 遐), hit-tau (彼兜)

- what - siáⁿ-mih [siánn-mih] (啥物), sīm-mi̍h (甚物), sīm-mô͘ [sīm-môo](甚麼)

- when - tī-sî (底時), kī-sî (幾時), tang-sî (當時), sīm-mi̍h-sî-chūn [sīm-mi̍h-sî-tsūn] (甚麼時陣)

- where - tó-lo̍h (佗落, 倒落), tó-ūi [tó-uī] (倒位, 佗位, 叨位)

- who - siáⁿ-lâng [siánn-lâng] (啥人) or siáⁿ-nga̍h [siánn-nga̍h] (啥nga̍h) or siáⁿ [siánn] (啥)

- why - ūi-siáⁿ-mi̍h [ūi-siánn-mi̍h] (為啥物), ka-nà (ka哪)

- how - án-chóaⁿ [án-tsuánn]" (按怎), chóaⁿ [tsuánn] (怎)

References

- Teresita Ang-See, "Chinese in the Philippines", 1997, Kaisa, pg. 57.

- http://www.admu.edu.ph/ls/soss/chinese-studies

- https://www.cksc.edu.ph/language-center-footer

- http://www.gitl.ntu.edu.tw/files/publish/11_a05f144a.pdf]

- Chang, Principles of POJ, p. 33.