| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Janet Douglas | -- | 2028 | 2022-09-29 17:28:15 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | + 3 word(s) | 2031 | 2022-09-30 03:37:39 | | | | |

| 3 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 2031 | 2022-10-08 10:20:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

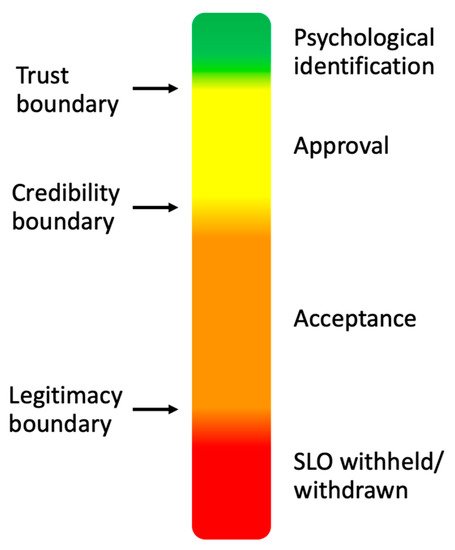

The concept of ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO) is relevant to all animal-use activities. An SLO is an intangible, implicit agreement between the public and an industry/group. Its existence allows that industry/group to pursue its activities with minimal formalised restrictions because such activities have widespread societal approval. In contrast, the imposition of legal restrictions—or even an outright ban—reflect qualified or lack of public support for an activity. The aim herein is to discuss current threats to equestrianism’s SLO and suggest actions that those across the equine sector need to take to justify the continuation of the SLO. The most important of these is earning the trust of all stakeholders, including the public. Trust requires transparency of operations, establishment and communication of shared values, and demonstration of competence. These attributes can only be gained by taking an ethics-based, proactive, progressive, and holistic approach to the protection of equine welfare. Animal-use activities that have faced challenges to their SLO have achieved variable success in re-establishing the approval of society, and equestrianism can learn from the experience of these groups as it maps its future. The associated effort and cost should be regarded as an investment in the future of the sport.

1. Introduction

2. How Is the Social Licence Concept Relevant to Equestrianism?

3. What Underlies the Threat to Equestrianism’s SLO?

4. What Have the Sports’ Regulatory Bodies done to Date to Maintain Equestrianism’s Social Licence?

References

- Gehman, J.; Lefsrud, L.M.; Fast, S. Social license to operate: Legitimacy by another name? Cdn. Public Adm. J. 2017, 60, 293–317.

- Hampton, J.O.; Jones, B.; McGreevy, P.D. Social License and Animal Welfare: Developments from the Past Decade in Australia. Animals 2020, 10, 2237.

- Campbell, M.L.H. Animals, Ethics and Us; 5m Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2019; pp. 69–97.

- Duncan, E.; Graham, R.; McManus, P. ‘No one has even seen… smelt… or sensed a social licence’: Animal geographies and social licence to operate. Geoforum 2018, 96, 318–327.

- Heleski, C.; Stowe, J.; Fiedler, J.; Peterson, M.L.; Brady, C.; Wickens, C.; MacLeod, J.N. Thoroughbred Racehorse Welfare through the Lens of ‘Social License to Operate with an Emphasis on a U.S. Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1706.

- Jones, E. Major Change Needed to Prevent Future Pentathlon Issues. Horse & Hound. 2021. Available online: https://www.horseandhound.co.uk/news/major-change-needed-to-prevent-future-pentathlon-issues-758542?fbclid=IwAR3Zm7ubGEL1iWwetmy-6R7mCXW265v-GX1CjXm3m6QiASaGRFBbn0cdvoU (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Fiedler, J.; Thomas, M.; Ames, K. Informing a social license to operate communication framework: Attitudes to sport horse welfare. In Proceedings of the 15th International Society of Equitation Science Conference, Guelph, ON, Canada, 19–21 August 2019; p. 52.

- Prno, J.; Slocombe, D.S. Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’ in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resour Policy 2012, 37, 346–357.

- Arnot, C. Lost in Translation: Learning to Speak “Consumer” in a Way That Builds Trust. 2011. Available online: https://vimeo.com/32552398 (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Raufflet, E.; Baba, S.; Perras, C.; Delannon, N. Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; p. 82.

- Thomson, I.; Boutilier, R.G. Social license to operate. In SME Mining Engineering Handbook; Darling, P., Ed.; Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration: Littleton, CO, USA, 2011; pp. 1779–1796.

- Merriam-Webster. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/equestrianism (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). Welfare of working equids. In Terrestrial Animal Health Code—19/07/2021; Available online: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahc/current/chapitre_aw_working_equids.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Laurence, D. The devolution of the social licence to operate in the Australian mining industry. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100742.

- McHugh, M. Special Commission of Inquiry into the Greyhound Racing Industry in New South Wales: Volume 1. Report, State of NSW, 16 June. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016-07/apo-nid65365_5.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Darimont, C.T.; Hall, H.; Eckert, L.; Mihalik, I.; Artelle, K.; Treves, A.; Paquet, P.C. Large carnivore hunting and the social license to hunt. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1111–1119.

- Hughes, M.; Townend, M. Jockey Club Execs Are Still Hunting for a Cheltenham Gold Cup Sponsor, with the Festival’s Reputation in Tatters over Claims It Was a 2020 COVID Super-Spreader after 250,000 Were Allowed in as the Virus Gripped the UK. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/racing/article-10395831/COVID-hangover-hits-Cheltenhams-Gold-Cup-sponsor-hunt-just-two-months-Festival.html (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Giles, T. Sponsors Drop World Number One Townend after Badminton Whipping Scandal. Inside the Games. Available online: https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/1065083/sponsors-drop-world-number-one-townend-after-badminton-whipping-scandal (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Godfrey, M. NSW Greyhound Racing Industry to Be Shut Down from 2017. Available online: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/nsw-greyhound-racing-industry-to-be-shut-down-from-2017/news-story/3d45e451862a9873d3ae506afdcd8458 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Markwell, K.; Firth, T.; Hing, N. Blood on the race track: An analysis of ethical concerns regarding animal-based gambling. Ann. Leis. Res. 2017, 20, 594–609.

- RSPCA South Australia. Jumps Racing. Available online: https://www.rspcasa.org.au/the-issues/jumps-racing/ (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Davey, L. New South Wales to Ban Greyhound Racing from Next Year after Live-Baiting Scandal. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/jul/07/new-south-wales-to-ban-greyhound-racing-from-next-year-after-cruelty-investigation (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Phillips, C. New South Wales Overturns Greyhound Ban: A Win for the Industry, but a Massive Loss for the Dogs. Available online: https://theconversation.com/new-south-wales-overturns-greyhound-ban-a-win-for-the-industry-but-a-massive-loss-for-the-dogs-66822 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Pittman, C. The Era of Greyhound Racing in the U.S. Is Coming to an End. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/greyhound-racing-decline-united-states (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Michigan State University. Overview of Dog Racing Laws. Available online: https://www.animallaw.info/article/overview-dog-racing-laws (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Benyon, R.H.R. The Defra View. In Proceedings of the 30th National Equine Forum, London, England, 3 March 2022; Parliamentary Under Secretary of State: Defra, UK, 2022.

- Taylor, J. I Can’t Watch Anymore; Epona Media: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; pp. 20–102.

- DW. Tokyo 2020: German Coach Suspended for Punching Horse at Olympics. 2020. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/tokyo-2020-german-coach-suspended-for-punching-horse-at-olympics/a-58790897 (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses. Available online: https://horseracingkills.com/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Peta Asia. Horse ‘Jet Set’ Is Euthanized after Competing at the Tokyo Olympics. Available online: https://www.petaasia.com/news/horse-jet-set-euthanized-tokyo-olympics/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- May, J. Medina Spirit Death: Why Have so Many Horses Died at Santa Anita. Available online: https://en.as.com/en/2021/12/07/other_sports/1638855620_335149.html (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Animal Aid. About Animal Aid. Available online: https://www.animalaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/About-Animal-Aid-factsheet.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Animal Aid. Achievements. Available online: https://www.animalaid.org.uk/about-us/animal-aid-achievements/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- RSPCA. Animal Welfare in Horse Racing. Available online: https://www.rspca.org.au/take-action/animal-welfare-in-horse-racing (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- RSPCA Australia. Charity Details. Available online: https://www.acnc.gov.au/charity/charities/0be192df-38af-e811-a963-000d3ad244fd/profile (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority. Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority. Available online: https://www.hisaus.org/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. FEI Suspends UAE National Federation for Rules Violations. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/media-updates/fei-suspends-uae-national-federation-rules-violations. (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Dombreval, L. Bien-être équin. Recommandations pour lez Jeux Olympiques de Paris 2024. Available online: https://loicdombreval.fr/pour-les-animaux1/rapport-sur-le-bien-etre-des-chevaux/ (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Carpenter, S.C.; Konisky, D.M. The killing of Cecil the Lion as an impetus for policy change. Oryx 2017, 53, 698–706.

- Cuckson, P. Modern Pentathlon: Nothing, Yet Everything, to Do with Us. 2021. Available online: https://horsesport.com/cuckson-report-1/modern-pentathlon-nothing-yet-everything/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Dane, K. Institutionalized horse abuse: The soring of Tennessee Walking Horses. Ky. J. Equine Agric. Nat. Resour. Law 2011, 3, 201–219.

- Cuckson, P. Endurance: No Gain Without Pain, but Who Will Make the Sacrifice? Available online:https://horsesport.com/cuckson-report-1/endurance-no-gain-without-pain-but-who-will-make-the-sacrifice/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Lesté-Lasserre, C. Researcher: Horse Sports Risk Losing ‘Social License. Available online: https://thehorse.com/181926/researcher-horse-sports-risk-losing-social-license/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Reuters. American Showjumper Given 10-Year Ban for Using Electric Spurs on His Horses. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/apr/22/american-showjumper-given-10-year-ban-for-using-electric-spurs-on-his-horses (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- MacIntyre, D. Horse Racing: Thousands of Racehorses Killed in Slaughterhouses. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-57881979 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- ABC News. The Dark Side of Australia’s Horse RACING industry. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zp-ALoBRW20 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Horsetalk.co.nz. Strongest Sanctions in FEI History Imposed in Fatal Endurance Case. Available online: https://www.horsetalk.co.nz/2020/06/09/strongest-sanctions-fei-history-fatal-endurance/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Hampton, J.O.; Teh-White, K. Animal welfare, social license, and wildlife use industries. J. Wildl. Manag. 2018, 83, 12–21.

- Mkono, M.; Holder, A. The future of animals in tourism recreation: Social media as spaces of collective moral reflexivity. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 1–8.

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1870.

- Scanes, C.G. Animals and Human Society; Elsevier: London, UK, 2018; pp. 240–243.

- Bryant, C.J. We Can’t Keep Meating Like This: Attitudes Towards Vegetarian and Vegan Diets in the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6844.

- Cuckson, P. Dressage Olympian Banned Three Years for Abusing Daughter’s Pony. 2021b. Available online: https://horsesport.com/horse-news/dressage-olympian-banned-three-years-abusing-daughters-pony/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Wood, G. Gordon Elliott’s Horrific Dead Horse Photo Has Left the Racing World Numb with Shock. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/mar/01/gordon-elliott-horrific-dead-horse-photo-racing-comment (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Bhati, A.; McDonnell, D. Success in an online giving day: The role of social media in fundraising. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2020, 49, 74–92.

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs and the Rt Hon Lord Goldsmith. Animals to be formally recognised as sentient beings in domestic law. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/animals-to-be-formally-recognised-as-sentient-beings-in-domestic-law (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- European Commission. Animal Welfare. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/animals/animal-welfare_en (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Walker, M.; Diez-Leon, M.; Mason, G. Animal Welfare Science: Recent Publication Trends and Future Research Priorities. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2014, 27, 80–100.

- Doherty, O. ISES Council Officer Reports (2020–2021). Available online: https://equitationscience.com/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Marlin, D. Dr. David Marlin. Available online: https://drdavidmarlin.com/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Duffy, M. The Internet as a Research and Dissemination Resource. Health Promot. Intl. 2000, 15, 349–353.

- Anonymous. Early Days. In The Daily Telegraph Chronicle of Horse Racing; Barrett, N., Ed.; Guinness Publishing: Enfield, Middlesex, UK, 1995; p. 8.

- British Horseracing Authority. “A Life Well-Lived”—British Racing’s Horse Welfare Board Publishes Five-Year Welfare Strategy. Available online: https://www.britishhorseracing.com/press_releases/a-life-well-lived-british-racings-horse-welfare-board-publishes-five-year-welfare-strategy/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- British Horseracing Authority. ‘The Horse Comes First’ Campaign. Available online: https://www.britishhorseracing.com/press_releases/british-racing-comes-together-to-promote-the-sports-commitment-to-welfare-through-the-horse-comes-first-campaign/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- New Zealand Thoroughbred Racing. Thoroughbred Welfare Assessment Guidelines. Available online: https://loveracing.nz/OnHorseFiles/NZTR%20Thoroughbred%20Welfare%20Guidelines%202020%20Final.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- International Federation of Horseracing Authorities. IFHA Minimum Horse Welfare Standards. Available online: https://www.ifhaonline.org/resources/IFHA_Minimum_Welfare_Standards.PDF (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. FEI Code of Conduct for the Welfare of the Horse. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/sites/default/files/Code_of_Conduct_Welfare_Horse_1Jan2013.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Louisiana State Legislature. HB384. Available online: http://www.legis.la.gov/legis/BillInfo.aspx?i=236200 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Thoroughbred Aftercare Welfare Working Group. A Framework for Thoroughbred Welfare. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e3788c2c2cd171e7c97ba5b/t/619eae9486659c7cf2342ff9/1637789384277/TWI_The+Most+Important+Participant (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Poncet, P.-A.; Bachmann, I.; Burkhardt, R.; Ehrbar, B.; Herrmann, R.; Friedli, K.; Leuenberger, H.; Lüth, A.; Montavon, S.; Pfammatter, M.; et al. Ethical Reflections on the Dignity and Welfare of Horses and Other Equids—Pathways to Enhanced Protection. Summary Report. Available online: https://www.cofichev.ch/fr/Publications.html (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority. 2000 Safety Racetrack Program. Available online: https://www.hisausregs.org/promulgated-regulations (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- The Racing Foundation and Horse Welfare Board. Aftercare Funding Review. Available online: http://media.britishhorseracing.com/bha/welfare/HWB/Aftercare_Funding_Review_March_2021.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- The Horse Trust. Our Healthiest Body Condition Rosettes Are Rolled out UK Wide. Available online: https://horsetrust.org.uk/best-body-condition-rosettes-are-uk-wide/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. FEI Endurance Rules. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/sites/default/files/FEI%20Endurance%20Rules%20-%201%20July%202020%20-%2016.12.2019%20-%20Clean.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- The Jockey Club. Winners of the 2019 Randox Health Grand National Best-Shod Horse Award. Available online: https://www.thejockeyclub.co.uk/aintree/media/news/2019/04/winners-of-the-2019-randox-health-grand-national--best-shod-horse-award/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Retraining of Racehorses. Retraining of Racehorses. Available online: https://www.ror.org.uk/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- British Horseracing Authority. Making Horseracing Safer. Available online: https://www.britishhorseracing.com/regulation/making-horseracing-safer/ (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. Deformable & Frangible Devices. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/fei/disc/eventing/risk-management/devices (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- British Eventing. Rules and Safety. Available online: https://www.britisheventing.com/compete/rules-and-safety (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- GrandNational.org.uk. Grand National Fences and Course. Available online: https://www.grandnational.org.uk/fences.php (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Eldridge, T.A.; Fadahunsi, L.; Goody, N.; Ioannilli, B.; Unwin, H.J.; Uthayakumar, P.; Wimshurst, A. Safer Horse Racing Hurdles, University of Southampton Group Design Project (Mechanical Engineering); University of Southampton: Southampton, Hampshire, UK, April 2014; unpublished work.

- University of Exeter. Racing Looks through Eyes of Horses to Help Deliver Improved Safety at All British Jump Courses. Available online: https://www.exeter.ac.uk/news/research/title_899819_en.html (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- The Jockey Club. Welfare at the Racecourse. Available online: https://www.thejockeyclub.co.uk/aintree/horse-welfare/horse-welfare-racing-and-facilities (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. FEI Stewards Manual—Dressage. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/sites/default/files/Dressage%20Stewards%20Manual%202019_clean_update10.11.21.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Dansk Ride Forbund. Fælles Bestemmelser. Available online: https://rideforbund.dk/Files/Files/PDF-filer/Reglement/F%C3%A6lles%20Bestemmelser%202022%20uden%20synlige%20rettelser.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. FEI Stewards Manual—Eventing. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/sites/default/files/Stewards%20Manual%20%20Eventing_January%202019.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. Horse Form Index (HFI). Available online: https://inside.fei.org/fei/disc/eventing/risk-management/hfi (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Marlin, D.; Misheff, M.; Whitehead, P. Preparation for and Management of Horses and Athletes during Equestrian Events Held in Thermally Challenging Environments. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/system/files/PREPARATION%20FOR%20AND%20MANAGEMENT%20DURING%20EQUESTRIAN%20EVENTS%20HELD%20IN%20THERMALLY%20CHALLENGING%20ENVIRONMENTS%20Final.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. 2022 Veterinary Regulations. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/sites/default/files/Veterinary%20Regulations%202022%20Clean%20version.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Jones, E. Untouched Whiskers ‘Becoming the Norm’ as Major Show Bans Trimming. Available online: https://www.horseandhound.co.uk/news/untouched-whiskers-becoming-the-norm-as-major-show-bans-trimming-769954 (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Great Yorkshire Show. Equine Schedule. 2022. Available online: https://greatyorkshireshow.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/equine-schedule-2022-v4.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Equestrian Australia. Guide to Horse Capacity—Size of Athlete. Available online: https://www.equestrian.org.au/sites/default/files/Guide%20to%20Horse%20Capacity%20-%20Size%20of%20Athlete%20_20%20January%202022.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. Blood during Competition. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/system/files/VET_BLOOD_DURING_COMPETITION.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Scargill, P. Sweden Bans Use of Whip for Encouragement from New Season in April. Available online: https://www.racingpost.com/news/sweden-bans-use-of-whip-for-encouragement-from-new-season-in-april/534662 (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Jones, B.; Goodfellow, J.; Yeates, J.; McGreevy, P.D. A Critical Analysis of the British Horseracing Authority’s Review of the Use of the Whip in Horseracing. Animals 2015, 5, 138–150.

- Dansk Travsports Centralforbund. Travkalender: Vedtægter. Available online: https://www.trav.dk/media/2121/travkalender_1_2022_webversion-3.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Dansk Galop. Skandinavisk Reglement for Galopløb SRG. Available online: https://danskgalop.dk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Skandinavisk-reglement-SRG-18.04.2022.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- British Horseracing Authority. The Whip. Available online: https://www.britishhorseracing.com/regulation/the-whip-2/ (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Congress.gov. H.R.693—PAST Act. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/693?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22tennessee+walker+past+soring%22%2C%22tennessee%22%2C%22walker%22%2C%22past%22%2C%22soring%22%5D%7D&s=3&r=1 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Furtado, T.; Preshaw, L.; Hockenhull, J.; Wathan, J.; Douglas, J.; Horseman, S.; Smith, R.; Pollard, D.; Pinchbeck, G.; Rogers, J.; et al. How Happy Are Equine Athletes? Stakeholder Perceptions of Equine Welfare Issues Associated with Equestrian Sport. Animals 2021, 11, 3228.