| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 7147 | 2022-09-28 01:43:48 |

Video Upload Options

Kanner autism, or classic autism, is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by challenges with social communication, and by restricted and repetitive behaviors. It is now considered part of the wider autism spectrum. The term 'autism' was historically used to refer specifically to Kanner autism, which is the convention used in this entry, but it is now more commonly used for the spectrum at large. Parents often notice signs of autism during the first three years of their child's life. These signs often develop gradually, though some autistic children experience regression in their communication and social skills after reaching developmental milestones at a normal pace. Autism has been hypothesized to be associated with a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Risk factors during pregnancy include certain infections, such as rubella, toxins including valproic acid, alcohol, cocaine, pesticides, lead, and air pollution, fetal growth restriction, and autoimmune diseases. Controversies surround other proposed environmental causes; for example, the vaccine hypothesis, which although disproven, continues to hold sway in certain communities. Autism affects information processing in the brain and how nerve cells and their synapses connect and organize; how this occurs is not well understood. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) combines forms of the condition, including high functioning autism (HFA), which was formerly known as Asperger syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) into the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Several interventions have been shown to reduce symptoms and improve the ability of autistic people to function and participate independently in the community. Behavioral, psychological, education, and/or skill-building interventions may be used to assist autistic people to learn life skills necessary for living independently, as well as other social, communication, and language skills. Therapy also aims to reduce challenging behaviors and build upon strengths. Some autistic adults are unable to live independently. An autistic culture has developed, with some individuals seeking a cure and others believing autism should be accepted as a difference to be accommodated instead of cured. Globally, autism is estimated to affect 24.8 million people (As of 2015). In the 2000s, the number of autistic people worldwide was estimated at 1–2 per 1,000 people. In the developed countries, about 1.5% of children are diagnosed with ASD (As of 2017), up from 0.7% in 2000 in the United States. It is diagnosed four to five times more often in males than females. The number of people diagnosed has increased considerably since the 1990s, which may be partly due to increased recognition of the condition.

1. Characteristics

Autism is a highly variable neurodevelopmental disorder[1] whose symptoms first appear during infancy or childhood, and generally follows a steady course without remission.[2] Autistic people may be severely impaired in some respects but average, or even superior, in others.[3] Overt symptoms gradually begin after the age of six months, become established by age two or three years[4] and tend to continue through adulthood, although often in more muted form.[5] It is distinguished by a characteristic triad of symptoms: impairments in social interaction, impairments in communication, and repetitive behavior. Other aspects, such as atypical eating, are also common but are not essential for diagnosis.[6] Individual symptoms of autism occur in the general population and appear not to associate highly, without a sharp line separating pathologically severe from common traits.[7]

1.1. Social Development

Social deficits distinguish autism and the related autism spectrum disorders (ASD; see Classification) from other developmental disorders.[5] Autistic people have social impairments and often lack the intuition about others that many people take for granted. Noted autistic Temple Grandin described her inability to understand the social communication of neurotypicals, or people with typical neural development, as leaving her feeling "like an anthropologist on Mars".[8]

Unusual social development becomes apparent early in childhood. Autistic infants show less attention to social stimuli, smile and look at others less often, and respond less to their own name. Autistic toddlers differ more strikingly from social norms; for example, they have less eye contact and turn-taking, and do not have the ability to use simple movements to express themselves, such as pointing at things.[9] Three- to five-year-old autistic children are less likely to exhibit social understanding, approach others spontaneously, imitate and respond to emotions, communicate nonverbally, and take turns with others. However, they do form attachments to their primary caregivers.[10] Most autistic children display moderately less attachment security than neurotypical children, although this difference disappears in children with higher mental development or less pronounced autistic traits.[11] Older children and adults with ASD perform worse on tests of face and emotion recognition[12] although this may be partly due to a lower ability to define a person's own emotions.[13]

Children with high-functioning autism have more intense and frequent loneliness compared to non-autistic peers, despite the common belief that autistic children prefer to be alone. Making and maintaining friendships often proves to be difficult for autistic people. For them, the quality of friendships, not the number of friends, predicts how lonely they feel. Functional friendships, such as those resulting in invitations to parties, may affect the quality of life more deeply.[14]

There are many anecdotal reports, but few systematic studies, of aggression and violence in individuals with ASD. The limited data suggest that, in children with intellectual disability, autism is associated with aggression, destruction of property, and meltdowns.[15]

1.2. Communication

About one third to half of autistic people do not develop enough natural speech to meet their daily communication needs.[16] Differences in communication may be present from the first year of life, and may include delayed onset of babbling, unusual gestures, diminished responsiveness, and vocal patterns that are not synchronized with the caregiver. In the second and third years, autistic children have less frequent and less diverse babbling, consonants, words, and word combinations; their gestures are less often integrated with words. Autistic children are less likely to make requests or share experiences, and are more likely to simply repeat others' words (echolalia)[17][18] or reverse pronouns.[19] Joint attention seems to be necessary for functional speech, and deficits in joint attention seem to distinguish infants with ASD.[20] For example, they may look at a pointing hand instead of the object to which the hand is pointing,[9][18] and they consistently fail to point at objects in order to comment on or share an experience.[20] Autistic children may have difficulty with imaginative play and with developing symbols into language.[17][18]

In a pair of studies, high-functioning autistic children aged 8–15 performed equally well as, and as adults better than, individually matched controls at basic language tasks involving vocabulary and spelling. Both autistic groups performed worse than controls at complex language tasks such as figurative language, comprehension, and inference. As people are often sized up initially from their basic language skills, these studies suggest that people speaking to autistic individuals are more likely to overestimate what their audience comprehends.[21]

1.3. Repetitive Behavior

Autistic individuals can display many forms of repetitive or restricted behavior, which the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) categorizes as follows.[22]

- Stereotyped behaviors: Repetitive movements, such as hand flapping, head rolling, or body rocking.

- Compulsive behaviors: Time-consuming behaviors intended to reduce the anxiety that an individual feels compelled to perform repeatedly or according to rigid rules, such as placing objects in a specific order, checking things, or handwashing.

- Sameness: Resistance to change; for example, insisting that the furniture not be moved or refusing to be interrupted.

- Ritualistic behavior: Unvarying pattern of daily activities, such as an unchanging menu or a dressing ritual. This is closely associated with sameness and an independent validation has suggested combining the two factors.[22]

- Restricted interests: Interests or fixations that are abnormal in theme or intensity of focus, such as preoccupation with a single television program, toy, or game.

- Self-injury: Behaviors such as eye-poking, skin-picking, hand-biting and head-banging.[20]

No single repetitive or self-injurious behavior seems to be specific to autism, but autism appears to have an elevated pattern of occurrence and severity of these behaviors.[23]

1.4. Other Symptoms

Autistic individuals may have symptoms that are independent of the diagnosis, but that can affect the individual or the family.[6] An estimated 0.5% to 10% of individuals with ASD show unusual abilities, ranging from splinter skills such as the memorization of trivia to the extraordinarily rare talents of prodigious autistic savants.[24] Many individuals with ASD show superior skills in perception and attention, relative to the general population.[25] Sensory abnormalities are found in over 90% of autistic people, and are considered core features by some,[26] although there is no good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate autism from other developmental disorders.[27] Differences are greater for under-responsivity (for example, walking into things) than for over-responsivity (for example, distress from loud noises) or for sensation seeking (for example, rhythmic movements).[28] An estimated 60–80% of autistic people have motor signs that include poor muscle tone, poor motor planning, and toe walking;[26][29] deficits in motor coordination are pervasive across ASD and are greater in autism proper.[30] Unusual eating behavior occurs in about three-quarters of children with ASD, to the extent that it was formerly a diagnostic indicator. Selectivity is the most common problem, although eating rituals and food refusal also occur.[31]

There is tentative evidence that gender dysphoria occurs more frequently in autistic people (see Autism and LGBT identities).[32][33] As well as that, a 2021 anonymized online survey of 16-90 year-olds revealed that autistic males are more likely to be bisexual, while autistic females are more likely to be homosexual.[34]

Gastrointestinal problems are one of the most commonly co-occurring medical conditions in autistic people.[35] These are linked to greater social impairment, irritability, behavior and sleep problems, language impairments and mood changes.[35][36]

Parents of children with ASD have higher levels of stress.[9] Siblings of children with ASD report greater admiration of and less conflict with the affected sibling than siblings of unaffected children and were similar to siblings of children with Down syndrome in these aspects of the sibling relationship. However, they reported lower levels of closeness and intimacy than siblings of children with Down syndrome; siblings of individuals with ASD have greater risk of negative well-being and poorer sibling relationships as adults.[37]

2. Causes

It has long been presumed that there is a common cause at the genetic, cognitive, and neural levels for autism's characteristic triad of symptoms.[38] However, there is increasing suspicion that autism is instead a complex disorder whose core aspects have distinct causes that often co-occur.[38][39]

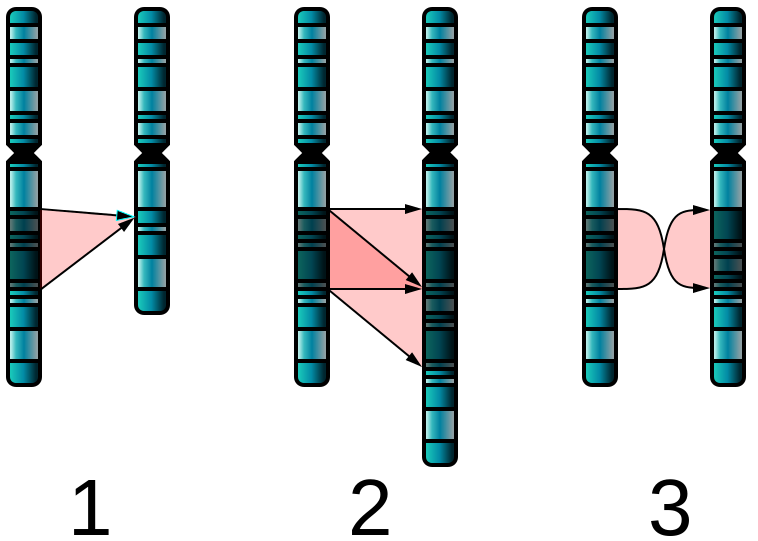

Autism has a strong genetic basis, although the genetics of autism are complex and it is unclear whether ASD is explained more by rare mutations with major effects, or by rare multigene interactions of common genetic variants.[41][42] Complexity arises due to interactions among multiple genes, the environment, and epigenetic factors which do not change DNA sequencing but are heritable and influence gene expression.[5] Many genes have been associated with autism through sequencing the genomes of affected individuals and their parents.[43] Studies of twins suggest that heritability is 0.7 for autism and as high as 0.9 for ASD, and siblings of those with autism are about 25 times more likely to be autistic than the general population.[26] However, most of the mutations that increase autism risk have not been identified. Typically, autism cannot be traced to a Mendelian (single-gene) mutation or to a single chromosome abnormality, and none of the genetic syndromes associated with ASDs have been shown to selectively cause ASD.[41] Numerous candidate genes have been located, with only small effects attributable to any particular gene.[41] Most loci individually explain less than 1% of cases of autism.[44] The large number of autistic individuals with unaffected family members may result from spontaneous structural variation—such as deletions, duplications or inversions in genetic material during meiosis.[45][46] Hence, a substantial fraction of autism cases may be traceable to genetic causes that are highly heritable but not inherited: that is, the mutation that causes the autism is not present in the parental genome.[40] Autism may be underdiagnosed in women and girls due to an assumption that it is primarily a male condition,[47] but genetic phenomena such as imprinting and X linkage have the ability to raise the frequency and severity of conditions in males, and theories have been put forward for a genetic reason why males are diagnosed more often, such as the imprinted brain hypothesis and the extreme male brain theory.[48][49][50]

Maternal nutrition and inflammation during preconception and pregnancy influences fetal neurodevelopment. Intrauterine growth restriction is associated with ASD, in both term and preterm infants.[51] Maternal inflammatory and autoimmune diseases may damage fetal tissues, aggravating a genetic problem or damaging the nervous system.[52]

Exposure to air pollution during pregnancy, especially heavy metals and particulates, may increase the risk of autism.[53][54] Environmental factors that have been claimed without evidence to contribute to or exacerbate autism include certain foods, infectious diseases, solvents, PCBs, phthalates and phenols used in plastic products, pesticides, brominated flame retardants, alcohol, smoking, illicit drugs, vaccines,[55] and prenatal stress. Some, such as the MMR vaccine, have been completely disproven.[56][57][58][59]

Parents may first become aware of autistic symptoms in their child around the time of a routine vaccination. This has led to unsupported theories blaming vaccine "overload", a vaccine preservative, or the MMR vaccine for causing autism.[60] The latter theory was supported by a litigation-funded study that has since been shown to have been "an elaborate fraud".[61] Although these theories lack convincing scientific evidence and are biologically implausible,[60] parental concern about a potential vaccine link with autism has led to lower rates of childhood immunizations, outbreaks of previously controlled childhood diseases in some countries, and the preventable deaths of several children.[62][63]

3. Mechanism

Autism's symptoms result from maturation-related changes in various systems of the brain. How autism occurs is not well understood. Its mechanism can be divided into two areas: the pathophysiology of brain structures and processes associated with autism, and the neuropsychological linkages between brain structures and behaviors.[64] The behaviors appear to have multiple pathophysiologies.[7]

There is evidence that gut–brain axis abnormalities may be involved.[35][36][65] A 2015 review proposed that immune dysregulation, gastrointestinal inflammation, malfunction of the autonomic nervous system, gut flora alterations, and food metabolites may cause brain neuroinflammation and dysfunction.[36] A 2016 review concludes that enteric nervous system abnormalities might play a role in neurological disorders such as autism. Neural connections and the immune system are a pathway that may allow diseases originated in the intestine to spread to the brain.[65]

Several lines of evidence point to synaptic dysfunction as a cause of autism.[66] Some rare mutations may lead to autism by disrupting some synaptic pathways, such as those involved with cell adhesion.[67] Gene replacement studies in mice suggest that autistic symptoms are closely related to later developmental steps that depend on activity in synapses and on activity-dependent changes.[68] All known teratogens (agents that cause birth defects) related to the risk of autism appear to act during the first eight weeks from conception, and though this does not exclude the possibility that autism can be initiated or affected later, there is strong evidence that autism arises very early in development.[69]

4. Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on behavior, not cause or mechanism.[7][70] Under the DSM-5, autism is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across multiple contexts, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These deficits are present in early childhood, typically before age three, and lead to clinically significant functional impairment.[71] Sample symptoms include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with unusual objects. The disturbance must not be better accounted for by Rett syndrome, intellectual disability or global developmental delay.[71] ICD-10 uses essentially the same definition.[2]

Several diagnostic instruments are available. Two are commonly used in autism research: the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) is a semistructured parent interview, and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)[72] uses observation and interaction with the child. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) is used widely in clinical environments to assess severity of autism based on observation of children.[9] The Diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders (DISCO) may also be used.[73]

A pediatrician commonly performs a preliminary investigation by taking developmental history and physically examining the child. If warranted, diagnosis and evaluations are conducted with help from ASD specialists, observing and assessing cognitive, communication, family, and other factors using standardized tools, and taking into account any associated medical conditions.[74] A pediatric neuropsychologist is often asked to assess behavior and cognitive skills, both to aid diagnosis and to help recommend educational interventions.[75] A differential diagnosis for ASD at this stage might also consider intellectual disability, hearing impairment, and a specific language impairment[74] such as Landau–Kleffner syndrome.[76] The presence of autism can make it harder to diagnose coexisting psychiatric disorders such as depression.[77]

Clinical genetics evaluations are often done once ASD is diagnosed, particularly when other symptoms already suggest a genetic cause.[78] Although genetic technology allows clinical geneticists to link an estimated 40% of cases to genetic causes,[79] consensus guidelines in the US and UK are limited to high-resolution chromosome and fragile X testing.[78] A genotype-first model of diagnosis has been proposed, which would routinely assess the genome's copy number variations.[80] As new genetic tests are developed several ethical, legal, and social issues will emerge. Commercial availability of tests may precede adequate understanding of how to use test results, given the complexity of autism's genetics.[81] Metabolic and neuroimaging tests are sometimes helpful, but are not routine.[78]

ASD can sometimes be diagnosed by age 14 months, although diagnosis becomes increasingly stable over the first three years of life: for example, a one-year-old who meets diagnostic criteria for ASD is less likely than a three-year-old to continue to do so a few years later.[82] In the UK the National Autism Plan for Children recommends at most 30 weeks from first concern to completed diagnosis and assessment, though few cases are handled that quickly in practice.[74] Although the symptoms of autism and ASD begin early in childhood, they are sometimes missed; years later, adults may seek diagnoses to help them or their friends and family understand themselves, to help their employers make adjustments, or in some locations to claim disability living allowances or other benefits.

Signs of autism may be more challenging for clinicians to detect in females.[83] Autistic females have been shown to engage in masking more frequently than autistic males.[83] Masking may include making oneself perform normative facial expressions and eye contact.[84] A notable percentage of autistic females may be misdiagnosed, diagnosed after a considerable delay, or not diagnosed at all.[83]

Conversely, the cost of screening and diagnosis and the challenge of obtaining payment can inhibit or delay diagnosis.[85] It is particularly hard to diagnose autism among the visually impaired, partly because some of its diagnostic criteria depend on vision, and partly because autistic symptoms overlap with those of common blindness syndromes or blindisms.[86]

4.1. Classification

Autism is one of the five pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), which are characterized by widespread abnormalities of social interactions and communication, severely restricted interests, and highly repetitive behavior.[2] These symptoms do not imply sickness, fragility, or emotional disturbance.[5]

Of the five PDD forms, Asperger syndrome is closest to autism in signs and likely causes; Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder share several signs with autism, but may have unrelated causes; PDD not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS; also called atypical autism) is diagnosed when the criteria are not met for a more specific disorder.[87] Unlike with autism, people with Asperger syndrome have no substantial delay in language development.[88] The terminology of autism can be bewildering, with autism, Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS often called the autism spectrum disorders (ASD)[89] or sometimes the autistic disorders,[90] whereas autism itself is often called autistic disorder, childhood autism, or infantile autism. In this article, autism refers to the classic autistic disorder; in clinical practice, though, autism, ASD, and PDD are often used interchangeably.[78] ASD, in turn, is a subset of the broader autism phenotype, which describes individuals who may not have ASD but do have autistic-like traits, such as avoiding eye contact.[91]

Research into causes has been hampered by the inability to identify biologically meaningful subgroups within the autistic population[92] and by the traditional boundaries between the disciplines of psychiatry, psychology, neurology and pediatrics.[93] Newer technologies such as fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging can help identify biologically relevant phenotypes (observable traits) that can be viewed on brain scans, to help further neurogenetic studies of autism;[94] one example is lowered activity in the fusiform face area of the brain, which is associated with impaired perception of people versus objects.[66] It has been proposed to classify autism using genetics as well as behavior.[95] (For more, see Brett Abrahams, geneticist and neuroscientist)

Spectrum

Autism has long been thought to cover a wide spectrum, ranging from individuals with severe impairments—who may be silent, developmentally disabled, and prone to frequent repetitive behavior such as hand flapping and rocking—to high functioning individuals who may have active but distinctly odd social approaches, narrowly focused interests, and verbose, pedantic communication.[96] Because the behavior spectrum is continuous, boundaries between diagnostic categories are necessarily somewhat arbitrary.[26]

5. Screening

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child's unusual behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months.[82] According to an article, failure to meet any of the following milestones "is an absolute indication to proceed with further evaluations. Delay in referral for such testing may delay early diagnosis and treatment and affect the long-term outcome".[6]

- No response to name (or eye-to-eye gaze) by 6 months.[97]

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force in 2016 found it was unclear if screening was beneficial or harmful among children in whom there is no concern.Template:Unbalanced inline[98] The Japanese practice is to screen all children for ASD at 18 and 24 months, using autism-specific formal screening tests. In contrast, in the UK, children whose families or doctors recognize possible signs of autism are screened. It is not known which approach is more effective.[66] Screening tools include the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire, and the First Year Inventory; initial data on M-CHAT and its predecessor, the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT), on children aged 18–30 months suggests that it is best used in a clinical setting and that it has low sensitivity (many false-negatives) but good specificity (few false-positives).[82] It may be more accurate to precede these tests with a broadband screener that does not distinguish ASD from other developmental disorders.[99] Screening tools designed for one culture's norms for behaviors like eye contact may be inappropriate for a different culture.[100] Although genetic screening for autism is generally still impractical, it can be considered in some cases, such as children with neurological symptoms and dysmorphic features.[101]

Some authors suggest that automatic motor assessment could be useful to screen the children with ASD[102] for instance with behavioural motor and emotionals reactions during smartphone watching.[103]

6. Prevention

While infection with rubella during pregnancy causes fewer than 1% of cases of autism,[104] vaccination against rubella can prevent many of those cases.[105]

7. Management

The main goals when treating autistic children are to lessen associated deficits and family distress, and to increase quality of life and functional independence. In general, higher IQs are correlated with greater responsiveness to treatment and improved treatment outcomes.[107][108] No single treatment is best and treatment is typically tailored to the child's needs.[89] Families and the educational system are the main resources for treatment.[66] Services should be carried out by behavior analysts, special education teachers, speech pathologists, and licensed psychologists. Studies of interventions have methodological problems that prevent definitive conclusions about efficacy.[109] However, the development of evidence-based interventions has advanced in recent years.[107] Although many psychosocial interventions have some positive evidence, suggesting that some form of treatment is preferable to no treatment, the methodological quality of systematic reviews of these studies has generally been poor, their clinical results are mostly tentative, and there is little evidence for the relative effectiveness of treatment options.[110] Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life can help children acquire self-care, communication, and job skills,[89] and often improve functioning and decrease symptom severity and maladaptive behaviors;[111] claims that intervention by around age three years is crucial are not substantiated.[112] While medications have not been found to help with core symptoms, they may be used for associated symptoms, such as irritability, inattention, or repetitive behavior patterns.[113]

7.1. Education

Educational interventions often used include applied behavior analysis (ABA), developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, social skills therapy, and occupational therapy and cognitive behavioral interventions in adults without intellectual disability to reduce depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[89][114] Among these approaches, interventions either treat autistic features comprehensively, or focalize treatment on a specific area of deficit.[107] The quality of research for early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI)—a treatment procedure incorporating over thirty hours per week of the structured type of ABA that is carried out with very young children—is currently low, and more vigorous research designs with larger sample sizes are needed.[115] Two theoretical frameworks outlined for early childhood intervention include structured and naturalistic ABA interventions, and developmental social pragmatic models (DSP).[107] One interventional strategy utilizes a parent training model, which teaches parents how to implement various ABA and DSP techniques, allowing for parents to disseminate interventions themselves.[107] Various DSP programs have been developed to explicitly deliver intervention systems through at-home parent implementation. Despite the recent development of parent training models, these interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in numerous studies, being evaluated as a probable efficacious mode of treatment.[107] File:Code of practice on provision of autism services.webm

Early, intensive ABA therapy has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing communication and adaptive functioning in preschool children;[89][116] it is also well-established for improving the intellectual performance of that age group.[89][111][116] Similarly, a teacher-implemented intervention that utilizes a more naturalistic form of ABA combined with a developmental social pragmatic approach has been found to be beneficial in improving social-communication skills in young children, although there is less evidence in its treatment of global symptoms.[107] Neuropsychological reports are often poorly communicated to educators, resulting in a gap between what a report recommends and what education is provided.[75] It is not known whether treatment programs for children lead to significant improvements after the children grow up,[111] and the limited research on the effectiveness of adult residential programs shows mixed results.[117] The appropriateness of including children with varying severity of autism spectrum disorders in the general education population is a subject of current debate among educators and researchers.[118]

7.2. Medication

Medications may be used to treat ASD symptoms that interfere with integrating a child into home or school when behavioral treatment fails.[119] They may also be used for associated health problems, such as ADHD or anxiety.[119] More than half of US children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics.[120][121] The atypical antipsychotic drugs risperidone and aripiprazole are FDA-approved for treating associated aggressive and self-injurious behaviors.[5][113][122] However, their side effects must be weighed against their potential benefits, and autistic people may respond atypically.[113] Side effects, for example, may include weight gain, tiredness, drooling, and aggression.[113] SSRI antidepressants, such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, have been shown to be effective in reducing repetitive and ritualistic behaviors, while the stimulant medication methylphenidate is beneficial for some children with co-morbid inattentiveness or hyperactivity.[89] There is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD. No known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments. Experiments in mice have reversed or reduced some symptoms related to autism by replacing or modulating gene function, suggesting the possibility of targeting therapies to specific rare mutations known to cause autism.[123]

7.3. Alternative Medicine

Although many alternative therapies and interventions are available, few are supported by scientific studies.[12] Treatment approaches have little empirical support in quality-of-life contexts, and many programs focus on success measures that lack predictive validity and real-world relevance.[14] Some alternative treatments may place the child at risk. The preference that autistic children have for unconventional foods can lead to reduction in bone cortical thickness with this being greater in those on casein-free diets, as a consequence of the low intake of calcium and vitamin D; however, suboptimal bone development in ASD has also been associated with lack of exercise and gastrointestinal disorders.[124] In 2005, botched chelation therapy killed a five-year-old child with autism.[125][126] Chelation is not recommended for autistic people since the associated risks outweigh any potential benefits.[127] Another alternative medicine practice with no evidence is CEASE therapy, a mixture of homeopathy, supplements, and 'vaccine detoxing'.

Although popularly used as an alternative treatment for autistic people, as of 2018 there is no good evidence to recommend a gluten- and casein-free diet as a standard treatment.[128][129][130] A 2018 review concluded that it may be a therapeutic option for specific groups of children with autism, such as those with known food intolerances or allergies, or with food intolerance markers. The authors analyzed the prospective trials conducted to date that studied the efficacy of the gluten- and casein-free diet in children with ASD (4 in total). All of them compared gluten- and casein-free diet versus normal diet with a control group (2 double-blind randomized controlled trials, 1 double-blind crossover trial, 1 single-blind trial). In two of the studies, whose duration was 12 and 24 months, a significant improvement in ASD symptoms (efficacy rate 50%) was identified. In the other two studies, whose duration was 3 months, no significant effect was observed.[128] The authors concluded that a longer duration of the diet may be necessary to achieve the improvement of the ASD symptoms.[128] Other problems documented in the trials carried out include transgressions of the diet, small sample size, the heterogeneity of the participants and the possibility of a placebo effect.[130][131] In the subset of people who have gluten sensitivity there is limited evidence that suggests that a gluten-free diet may improve some autistic behaviors.[132][133][134]

Results of a systematic review on interventions to address health outcomes among autistic adults found emerging evidence to support mindfulness-based interventions for improving mental health. This includes decreasing stress, anxiety, ruminating thoughts, anger, and aggression.[114] There is tentative evidence that music therapy may improve social interactions, verbal communication, and non-verbal communication skills.[135] There has been early research looking at hyperbaric treatments in children with autism.[136] Studies on pet therapy have shown positive effects.[137]

8. Prognosis

There is no known cure for autism.[66][89] The degree of symptoms can decrease, occasionally to the extent that people lose their diagnosis of ASD;[138] this occurs sometimes after intensive treatment and sometimes not. It is not known how often this outcome happens;[111] reported rates in unselected samples have ranged from 3% to 25%.[138] Most autistic children acquire language by age five or younger, though a few have developed communication skills in later years.[139] Many autistic children lack social support, future employment opportunities or self-determination.[14] Although core difficulties tend to persist, symptoms often become less severe with age.[5]

Few high-quality studies address long-term prognosis. Some adults show modest improvement in communication skills, but a few decline; no study has focused on autism after midlife.[140] Acquiring language before age six, having an IQ above 50, and having a marketable skill all predict better outcomes; independent living is unlikely with severe autism.[141]

Many autistic people face significant obstacles in transitioning to adulthood.[142] Compared to the general population autistic people are more likely to be unemployed and to have never had a job. About half of people in their 20s with autism are not employed.[143]

Autistic people tend to face increased stress levels related to psychosocial factors, such as stigma, which may increase the rates of mental health issues in the autistic population.[144]

9. Epidemiology

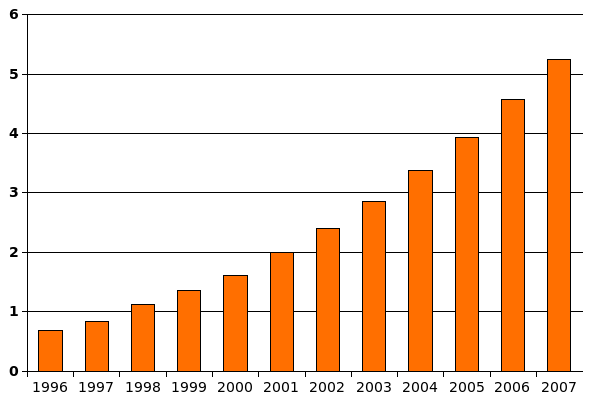

As of 2007, reviews estimate a prevalence of 1–2 per 1,000 for autism and close to 6 per 1,000 for ASD.[55] A 2016 survey in the United States reported a rate of 25 per 1,000 children for ASD.[145] Globally, autism affects an estimated 24.8 million people (As of 2015), while Asperger syndrome affects a further 37.2 million.[146] In 2012, the NHS estimated that the overall prevalence of autism among adults aged 18 years and over in the UK was 1.1%.[147] Rates of PDD-NOS's has been estimated at 3.7 per 1,000, Asperger syndrome at roughly 0.6 per 1,000, and childhood disintegrative disorder at 0.02 per 1,000.[148] CDC estimates about 1 out of 59 (1.7%) for 2014, an increase from 1 out of every 68 children (1.5%) for 2010.[149]

In the UK, from 1998 to 2018, the autism diagnoses increased by 787%.[150] This increase is largely attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, referral patterns, availability of services, age at diagnosis, and public awareness[148][151][152] (particularly among women),[150] though unidentified environmental risk factors cannot be ruled out.[153] The available evidence does not rule out the possibility that autism's true prevalence has increased;[148] a real increase would suggest directing more attention and funding toward psychosocial factors and changing environmental factors instead of continuing to focus on genetics.[154] It has been established that vaccination is not a risk factor for autism and is not behind any increase in autism prevalence rates, if any change in the rate of autism exists at all.[155]

Males are at higher risk for ASD than females. The sex ratio averages 4.3:1 and is greatly modified by cognitive impairment: it may be close to 2:1 with intellectual disability and more than 5.5:1 without.[55] Several theories about the higher prevalence in males have been investigated, but the cause of the difference is unconfirmed;[156] one theory is that females are underdiagnosed.[157]

Although the evidence does not implicate any single pregnancy-related risk factor as a cause of autism, the risk of autism is associated with advanced age in either parent, and with diabetes, bleeding, and use of psychiatric drugs in the mother during pregnancy.[156][158] The risk is greater with older fathers than with older mothers; two potential explanations are the known increase in mutation burden in older sperm, and the hypothesis that men marry later if they carry genetic liability and show some signs of autism.[1] Most professionals believe that race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background do not affect the occurrence of autism.[159]

Several other conditions are common in children with autism.[66] They include:

- Genetic disorders. About 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndrome,[160] and ASD is associated with several genetic disorders.[161]

- Intellectual disability. The percentage of autistic individuals who also meet criteria for intellectual disability has been reported as anywhere from 25% to 70%, a wide variation illustrating the difficulty of assessing intelligence of individuals on the autism spectrum.[162] In comparison, for PDD-NOS the association with intellectual disability is much weaker,[163] and by definition, the diagnosis of Asperger's excludes intellectual disability.[164]

- Anxiety disorders are common among children with ASD; there are no firm data, but studies have reported prevalences ranging from 11% to 84%. Many anxiety disorders have symptoms that are better explained by ASD itself, or are hard to distinguish from ASD's symptoms.[165]

- Epilepsy, with variations in risk of epilepsy due to age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder.[166]

- Several metabolic defects, such as phenylketonuria, are associated with autistic symptoms.[167]

- Minor physical anomalies are significantly increased in the autistic population.[168]

- Preempted diagnoses. Although the DSM-IV rules out the concurrent diagnosis of many other conditions along with autism, the full criteria for Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Tourette syndrome, and other of these conditions are often present and these co-occurrent conditions are increasingly accepted.

- Sleep problems affect about two-thirds of individuals with ASD at some point in childhood. These most commonly include symptoms of insomnia such as difficulty in falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and early morning awakenings. Sleep problems are associated with difficult behaviors and family stress, and are often a focus of clinical attention over and above the primary ASD diagnosis.[169]

10. History

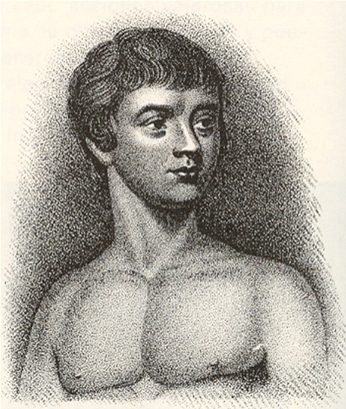

A few examples of autistic symptoms and treatments were described long before autism was named. The Table Talk of Martin Luther, compiled by his notetaker, Mathesius, contains the story of a 12-year-old boy who may have been severely autistic.[171] The earliest well-documented case of autism is that of Hugh Blair of Borgue, as detailed in a 1747 court case in which his brother successfully petitioned to annul Blair's marriage to gain Blair's inheritance.[172] The Wild Boy of Aveyron, a feral child caught in 1798, showed several signs of autism; the medical student Jean Itard treated him with a behavioral program designed to help him form social attachments and to induce speech via imitation.[170]

The New Latin word autismus (English translation autism) was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1910 as he was defining symptoms of schizophrenia. He derived it from the Greek word autós (αὐτός, meaning "self"), and used it to mean morbid self-admiration, referring to "autistic withdrawal of the patient to his fantasies, against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance".[173] A Soviet child psychiatrist, Grunya Sukhareva, described a similar syndrome that was published in Russian in 1925, and in German in 1926.[174]

10.1. Clinical Development and Diagnoses

The word autism first took its modern sense in 1938 when Hans Asperger of the Vienna University Hospital adopted Bleuler's terminology autistic psychopaths in a lecture in German about child psychology.[175] Asperger was investigating an ASD now known as Asperger syndrome, though for various reasons it was not widely recognized as a separate diagnosis until 1981.[170] Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital first used autism in its modern sense in English when he introduced the label early infantile autism in a 1943 report of 11 children with striking behavioral similarities.[19] Almost all the characteristics described in Kanner's first paper on the subject, notably "autistic aloneness" and "insistence on sameness", are still regarded as typical of the autistic spectrum of disorders.[39] It is not known whether Kanner derived the term independently of Asperger.[176]

Kanner's reuse of autism led to decades of confused terminology like infantile schizophrenia, and child psychiatry's focus on maternal deprivation led to misconceptions of autism as an infant's response to "refrigerator mothers". Starting in the late 1960s autism was established as a separate syndrome.[177]

10.2. Terminology and Distinction from Schizophrenia

As late as the mid-1970s there was little evidence of a genetic role in autism, while in 2007 it was believed to be one of the most heritable psychiatric conditions.[178] Although the rise of parent organizations and the destigmatization of childhood ASD have affected how ASD is viewed,[170] parents continue to feel social stigma in situations where their child's autistic behavior is perceived negatively,[179] and many primary care physicians and medical specialists express some beliefs consistent with outdated autism research.[180]

It took until 1980 for the DSM-III to differentiate autism from childhood schizophrenia. In 1987, the DSM-III-R provided a checklist for diagnosing autism. In May 2013, the DSM-5 was released, updating the classification for pervasive developmental disorders. The grouping of disorders, including PDD-NOS, autism, Asperger syndrome, Rett syndrome, and CDD, has been removed and replaced with the general term of Autism Spectrum Disorders. The two categories that exist are impaired social communication and/or interaction, and restricted and/or repetitive behaviors.[181]

The Internet has helped autistic individuals bypass nonverbal cues and emotional sharing that they find difficult to deal with, and has given them a way to form online communities and work remotely.[182] Societal and cultural aspects of autism have developed: some in the community seek a cure, while others believe that autism is simply another way of being.[183][184]

11. Society and Culture

An autistic culture has emerged, accompanied by the autistic rights and neurodiversity movements.[185][186][187] Events include World Autism Awareness Day, Autism Sunday, Autistic Pride Day, Autreat, and others.[188][189][190][191] Social-science scholars study those with autism in hopes to learn more about "autism as a culture, transcultural comparisons ... and research on social movements."[192] Many autistic individuals have been successful in their fields.[193][194][195]

11.1. Autism Rights Movement

The autism rights movement is a social movement within the context of disability rights that emphasizes the concept of neurodiversity, viewing the autism spectrum as a result of natural variations in the human brain rather than a disorder to be cured.[187] The autism rights movement advocates for including greater acceptance of autistic behaviors; therapies that focus on coping skills rather than on imitating the behaviors of those without autism, and the recognition of the autistic community as a minority group.[196] Autism rights or neurodiversity advocates believe that the autism spectrum is genetic and should be accepted as a natural expression of the human genome. This perspective is distinct from fringe theories that autism is caused by environmental factors such as vaccines.[187] A common criticism against autistic activists is that the majority of them are "high-functioning" or have Asperger syndrome and do not represent the views of "low-functioning" autistic people.[196]

11.2. Employment

About half of autistic people are unemployed, and one third of those with graduate degrees may be unemployed.[197] Among those who find work, most are employed in sheltered settings working for wages below the national minimum.[198] While employers state hiring concerns about productivity and supervision, experienced employers of autistic people give positive reports of above average memory and detail orientation as well as a high regard for rules and procedure in autistic employees.[197] A majority of the economic burden of autism is caused by decreased earnings in the job market.[199] Some studies also find decreased earning among parents who care for autistic children.[200][201]

References

- "Autism: many genes, common pathways?". Cell 135 (3): 391–395. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.016. PMID 18984147. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2756410

- "F84. Pervasive developmental disorders". World Health Organization. 2007. http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/?gf80.htm+f84.

- Biopsychology (8th ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson. 2011. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-205-03099-6. OCLC 1085798897. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1085798897

- "What are infant siblings teaching us about autism in infancy?". Autism Res 2 (3): 125–137. 2009. doi:10.1002/aur.81. PMID 19582867. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2791538

- "Autism: definition, neurobiology, screening, diagnosis". Pediatric Clinics of North America 55 (5): 1129–1146, viii. October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2008.07.005. PMID 18929056. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.pcl.2008.07.005

- "The screening and diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders". J Autism Dev Disord 29 (6): 439–484. 1999. doi:10.1023/A:1021943802493. PMID 10638459. This paper represents a consensus of representatives from nine professional and four parent organizations in the US. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FA%3A1021943802493

- "The role of the neurobiologist in redefining the diagnosis of autism". Brain Pathol 17 (4): 408–411. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00103.x. PMID 17919126. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=8095627

- An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales. New York: Knopf. 1995. ISBN 978-0-679-43785-7. OCLC 34359253. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/34359253

- Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Volume Two: Assessment, Interventions, and Policy. 2 (4th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. 2014. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-118-28220-5. OCLC 946133861. https://books.google.com/books?id=4yzqAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA301. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Early detection of core deficits in autism". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 10 (4): 221–233. 2004. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20046. PMID 15666338. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fmrdd.20046

- "Autism and attachment: a meta-analytic review". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 45 (6): 1123–1134. September 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00305.x. PMID 15257669. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00305.x

- "Autism from developmental and neuropsychological perspectives". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2: 327–355. 2006. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095210. PMID 17716073. https://dx.doi.org/10.1146%2Fannurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095210

- "Mixed emotions: the contribution of alexithymia to the emotional symptoms of autism". Translational Psychiatry 3 (7): e285. July 2013. doi:10.1038/tp.2013.61. PMID 23880881. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3731793

- "Quality of life for people with autism: raising the standard for evaluating successful outcomes". Child and Adolescent Mental Health 12 (2): 80–86. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00432.x. PMID 32811109. http://kingwoodpsychology.com/recent_publications/camh_432.pdf. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Assessing challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review". Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (6): 567–579. November 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2006.08.001. PMID 16973329. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ridd.2006.08.001

- "The ComFor: an instrument for the indication of augmentative communication in people with autism and intellectual disability". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 50 (9): 621–632. 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00807.x. PMID 16901289. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/handle/123456789/216355.

- "Early communication development and intervention for children with autism". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 13 (1): 16–25. 2007. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20134. PMID 17326115. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fmrdd.20134

- "Language disorders: autism and other pervasive developmental disorders". Pediatr Clin North Am 54 (3): 469–481. 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.02.011. PMID 17543905. https://www.academia.edu/19351942.

- "Autistic disturbances of affective contact". Nerv Child 2 (4): 217–250. 1943. PMID 4880460. Reprinted in "Autistic disturbances of affective contact". Acta Paedopsychiatr 35 (4): 100–136. 1968. PMID 4880460. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4880460

- "Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics 120 (5): 1183–1215. 2007. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2361. PMID 17967920. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/120/5/1183.

- "Neuropsychologic functioning in children with autism: further evidence for disordered complex information-processing". Child Neuropsychol 12 (4–5): 279–298. 2006. doi:10.1080/09297040600681190. PMID 16911973. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1803025

- "The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders". J Autism Dev Disord 37 (5): 855–866. 2007. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0213-z. PMID 17048092. https://www.academia.edu/14013119.

- "Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: comparisons to mental retardation". J Autism Dev Disord 30 (3): 237–243. 2000. doi:10.1023/A:1005596502855. PMID 11055459. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FA%3A1005596502855

- "The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 364 (1522): 1351–1357. 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0326. PMID 19528017. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2677584

- "Perception and apperception in autism: rejecting the inverse assumption". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 364 (1522): 1393–1398. 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0001. PMID 19528022. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2677593

- "Advances in autism". Annu Rev Med 60: 367–380. 2009. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.053107.121225. PMID 19630577. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3645857

- "Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence". J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46 (12): 1255–1268. 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x. PMID 16313426. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1469-7610.2005.01431.x

- "A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders". J Autism Dev Disord 39 (1): 1–11. 2009. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3. PMID 18512135. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10803-008-0593-3

- Gargot, Thomas; Archambault, Dominique; Chetouani, Mohamed; Cohen, David; Johal, Wafa; Anzalone, Salvatore Maria (2022-01-10). "Automatic Assessment of Motor Impairments in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review". Cognitive Computation. doi:10.1007/s12559-021-09940-8. ISSN 1866-9964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-021-09940-8. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- "Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis". J Autism Dev Disord 40 (10): 1227–1240. 2010. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-0981-3. PMID 20195737. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10803-010-0981-3

- "Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment". Res Dev Disabil 28 (2): 145–162. 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2006.02.003. PMID 16581226. https://www.academia.edu/19351952.

- "Gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder: A narrative review". International Review of Psychiatry 28 (1): 70–80. 2016. doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1111199. PMID 26753812. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109%2F09540261.2015.1111199

- "Gender Dysphoria and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Sexual Medicine Reviews 4 (1): 3–14. January 2016. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2015.10.003. PMID 27872002. https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/20811.

- Weir, Elizabeth; Allison, Carrie; Baron-Cohen, Simon (27 August 2021). "The sexual health, orientation, and activity of autistic adolescents and adults". Autism Research 14 (11): 2342–2354. doi:10.17863/CAM.74771. PMID 34536071. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/327322.

- "Serotonin as a link between the gut-brain-microbiome axis in autism spectrum disorders.". Pharmacol Res 132: 1–6. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2018.03.020. PMID 29614380. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6368356

- "Gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorder: links and risks - a possible new overlap syndrome.". Pediatric Health Med Ther 6: 153–166. 2015. doi:10.2147/PHMT.S85717. PMID 29388597. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5683266

- "Siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders across the life course". Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 13 (4): 313–320. 2007. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20171. PMID 17979200. http://www.waisman.wisc.edu/family/pubs/Autism/2007%20siblings_autism_life-course.pdf.

- "The 'fractionable autism triad': a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research". Neuropsychol Rev 18 (4): 287–304. 2008. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. PMID 18956240. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11065-008-9076-8

- "Time to give up on a single explanation for autism". Nature Neuroscience 9 (10): 1218–1220. 2006. doi:10.1038/nn1770. PMID 17001340. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnn1770

- "Autism: highly heritable but not inherited". Nature Medicine 13 (5): 534–536. May 2007. doi:10.1038/nm0507-534. PMID 17479094. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnm0507-534

- "Advances in autism genetics: on the threshold of a new neurobiology". Nature Reviews. Genetics 9 (5): 341–355. May 2008. doi:10.1038/nrg2346. PMID 18414403. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2756414

- "Multiple rare variants in the etiology of autism spectrum disorders". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 11 (1): 35–43. 2009. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/jdbuxbaum. PMID 19432386. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3181906

- "Insights into Autism Spectrum Disorder Genomic Architecture and Biology from 71 Risk Loci". Neuron 87 (6): 1215–1233. September 2015. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.016. PMID 26402605. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4624267

- "Autism genetics". Behavioural Brain Research 251: 95–112. August 2013. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2013.06.012. PMID 23769996. https://www.academia.edu/27774685.

- "Copy-number variations associated with neuropsychiatric conditions". Nature 455 (7215): 919–923. October 2008. doi:10.1038/nature07458. PMID 18923514. Bibcode: 2008Natur.455..919C. https://www.academia.edu/12729917.

- "Frequency and Complexity of De Novo Structural Mutation in Autism". American Journal of Human Genetics 98 (4): 667–679. April 2016. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.018. PMID 27018473. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4833290

- "Thousands of autistic girls and women 'going undiagnosed' due to gender bias". The Guardian. 14 September 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/sep/14/thousands-of-autistic-girls-and-women-going-undiagnosed-due-to-gender-bias.

- "Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain". The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 31 (3): 241–61; discussion 261–320. June 2008. doi:10.1017/S0140525X08004214. PMID 18578904. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/21571/1/Psychosis%20and%20autism%20as%20diametrical%20disorders%20of%20the%20social%20brain%20%28LSERO%29.pdf.

- "Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (Suppl 1): 1736–41. January 2010. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906080106. PMID 19955444. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..107.1736C. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2868282

- "Sex differences in the brain: implications for explaining autism". Science 310 (5749): 819–23. November 2005. doi:10.1126/science.1115455. PMID 16272115. Bibcode: 2005Sci...310..819B. http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/2710/1/219535_PubSub1971_Belmonte.pdf.

- "Neurodevelopment: The Impact of Nutrition and Inflammation During Preconception and Pregnancy in Low-Resource Settings". Pediatrics 139 (Suppl 1): S38–S49. 2017. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2828F. PMID 28562247. https://dx.doi.org/10.1542%2Fpeds.2016-2828F

- "Pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorders: revisiting gastrointestinal involvement and immune imbalance.". World J Gastroenterol 20 (29): 9942–9951. 2014. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.9942. PMID 25110424. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4123375

- "Maternal lifestyle and environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders". International Journal of Epidemiology 43 (2): 443–464. April 2014. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt282. PMID 24518932. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3997376

- "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Multiple Airborne Pollutants and Autism Spectrum Disorder". PLOS ONE 11 (9): e0161851. 2016. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161851. PMID 27653281. Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1161851L. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5031428

- "The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Annual Review of Public Health 28: 235–258. 2007. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. PMID 17367287. https://dx.doi.org/10.1146%2Fannurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007

- "Prenatal stress and risk for autism". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 32 (8): 1519–1532. October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.004. PMID 18598714. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2632594

- "The Anti-vaccination Movement: A Regression in Modern Medicine". Cureus 10 (7): e2919. July 2018. doi:10.7759/cureus.2919. PMID 30186724. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6122668

- "Vaccine Adverse Events: Separating Myth from Reality". American Family Physician 95 (12): 786–794. June 2017. PMID 28671426. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28671426

- Di Pietrantonj, Carlo; Rivetti, Alessandro; Marchione, Pasquale; Debalini, Maria Grazia; Demicheli, Vittorio (2021-11-22). "Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11: CD004407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 34806766. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=8607336

- "Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses". Clin Infect Dis 48 (4): 456–461. 2009. doi:10.1086/596476. PMID 19128068. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2908388

- "Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent". BMJ 342: c7452. 2011. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7452. PMID 21209060. http://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7452.full.

- Vaccines and autism: "Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature". Can J Neurol Sci 33 (4): 341–346. 2006. doi:10.1017/s031716710000528x. PMID 17168158. "Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses". Clin Infect Dis 48 (4): 456–461. 2009. doi:10.1086/596476. PMID 19128068. "A broken trust: lessons from the vaccine–autism wars". PLOS Biol 7 (5): e1000114. 2009. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000114. PMID 19478850. "Parents ask: am I risking autism if I vaccinate my children?". J Autism Dev Disord 39 (6): 962–963. 2009. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0739-y. PMID 19363650. http://works.bepress.com/rhea_paul/50. "The Age-Old Struggle against the Antivaccinationists". N Engl J Med 364 (2): 97–99. 13 January 2011. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1010594. PMID 21226573.

- "Measles outbreak in Dublin, 2000". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22 (7): 580–584. 2003. doi:10.1097/00006454-200307000-00002. PMID 12867830. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2F00006454-200307000-00002

- "Neurobiological correlates of autism: a review of recent research". Child Neuropsychol 12 (1): 57–79. 2006. doi:10.1080/09297040500253546. PMID 16484102. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F09297040500253546

- "The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13 (9): 517–528. September 2016. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.107. PMID 27435372. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5005185

- "Autism". Lancet 374 (9701): 1627–1638. 2009. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61376-3. PMID 19819542. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2863325

- "The emerging role of synaptic cell-adhesion pathways in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders". Trends Neurosci 32 (7): 402–412. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.04.003. PMID 19541375. http://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-00401195/en/.

- "Autism and brain development". Cell 135 (3): 396–400. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.015. PMID 18984148. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2701104

- "The teratology of autism". Int J Dev Neurosci 23 (2–3): 189–199. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001. PMID 15749245. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ijdevneu.2004.11.001

- "Diagnosis of autism". BMJ 327 (7413): 488–493. 2003. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7413.488. PMID 12946972. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=188387

- Autism Spectrum Disorder, 299.00 (F84.0). In: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- "A replication of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) revised algorithms". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 47 (6): 642–651. June 2008. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816bffb7. PMID 18434924. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3057666

- "[Autism spectrum disorders in adults]". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 152 (24): 1365–1369. June 2008. PMID 18664213. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18664213

- "How to diagnose autism". Arch Dis Child 92 (6): 540–545. 2007. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.086280. PMID 17515625. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2066173

- "Diagnostic and assessment findings: a bridge to academic planning for children with autism spectrum disorders". Neuropsychol Rev 18 (4): 367–384. 2008. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9072-z. PMID 18855144. https://www.academia.edu/14769718.

- "Autistic regression and Landau–Kleffner syndrome: progress or confusion?". Dev Med Child Neurol 42 (5): 349–353. 2000. doi:10.1017/S0012162200210621. PMID 10855658. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0012162200210621

- "Cormorbidity: diagnosing comorbid psychiatric conditions". Psychiatr Times 26 (4). 2009. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/display/article/10168/1403043.

- "Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers". Arch Dis Child 93 (6): 518–523. 2008. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.115337. PMID 18305076. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136%2Fadc.2006.115337

- "Genetics evaluation for the etiologic diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders". Genet Med 10 (1): 4–12. 2008. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815efdd7. PMID 18197051. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FGIM.0b013e31815efdd7

- "Cytogenetic technology—genotype and phenotype". N Engl J Med 359 (16): 1728–1730. 2008. doi:10.1056/NEJMe0806570. PMID 18784093. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMe0806570

- "Genetic counseling and ethical issues for autism". American Journal of Medical Genetics 142C (1): 52–57. 2006. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30082. PMID 16419100. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fajmg.c.30082

- "Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in the first 3 years of life". Nat Clin Pract Neurol 4 (3): 138–147. 2008. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0731. PMID 18253102. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fncpneuro0731

- "Brief Report: Sex/Gender Differences in Symptomology and Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 49 (6): 2597–2604. June 2019. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03998-y. PMID 30945091. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6753236

- ""Putting on My Best Normal": Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47 (8): 2519–2534. August 2017. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5. PMID 28527095. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5509825

- "Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 13 (2): 129–135. 2007. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20143. PMID 17563895. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fmrdd.20143

- "Visual impairment and autism: current questions and future research". Autism 2 (2): 117–138. 1998. doi:10.1177/1362361398022002. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F1362361398022002

- "Autism and autism spectrum disorders: diagnostic issues for the coming decade". J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50 (1–2): 108–115. 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02010.x. PMID 19220594. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1469-7610.2008.02010.x

- "Diagnostic criteria for 299.00 Autistic Disorder". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. 2000. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. OCLC 768475353. http://cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/hcp-dsm.html.

- "Management of children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics 120 (5): 1162–1182. November 2007. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2362. PMID 17967921. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/120/5/1162.

- "The genetics of autistic disorders and its clinical relevance: a review of the literature". Molecular Psychiatry 12 (1): 2–22. January 2007. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001896. PMID 17033636. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fsj.mp.4001896

- "Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families". Am J Psychiatry 154 (2): 185–190. 1997. doi:10.1176/ajp.154.2.185. PMID 9016266. https://dx.doi.org/10.1176%2Fajp.154.2.185

- "Autism and the environment: challenges and opportunities for research". Pediatrics 121 (6): 1225–1229. 2008. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3000. PMID 18519493. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/121/6/1225.

- "Childhood developmental disorders: an academic and clinical convergence point for psychiatry, neurology, psychology and pediatrics". J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50 (1–2): 87–98. 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02046.x. PMID 19220592. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5756732

- "Neural systems approaches to the neurogenetics of autism spectrum disorders". Neuroscience 164 (1): 247–256. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.054. PMID 19482063. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neuroscience.2009.05.054

- "Unraveling autism". American Journal of Human Genetics 82 (1): 7–9. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.003. PMID 18179879. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2253980

- "Understanding assets and deficits in autism: why success is more interesting than failure". Psychologist 12 (11): 540–547. 1999. http://www.thepsychologist.org.uk/archive/archive_home.cfm/volumeID_12-editionID_46-ArticleID_133-getfile_getPDF/thepsychologist/psy_11_99_p540-547_happe.pdf.

- "Autism case training part 1: A closer look – key developmental milestones". CDC.gov. 18 August 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/autism/case-modules/early-warning-signs/03-closer-look.html#tabs-1-1.

- "Screening for Autism Spectrum Disorder in Young Children: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA 315 (7): 691–696. February 2016. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0018. PMID 26881372. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.2016.0018

- "Validation of the Infant-Toddler Checklist as a broadband screener for autism spectrum disorders from 9 to 24 months of age". Autism 12 (5): 487–511. September 2008. doi:10.1177/1362361308094501. PMID 18805944. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2663025

- "The challenge of screening for autism spectrum disorder in a culturally diverse society". Acta Paediatrica 97 (5): 539–540. May 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00720.x. PMID 18373717. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1651-2227.2008.00720.x

- "Autistic phenotypes and genetic testing: state-of-the-art for the clinical geneticist". Journal of Medical Genetics 46 (1): 1–8. January 2009. doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.060871. PMID 18728070. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2603481

- Gargot, Thomas; Archambault, Dominique; Chetouani, Mohamed; Cohen, David; Johal, Wafa; Anzalone, Salvatore Maria (2022-01-10). "Automatic Assessment of Motor Impairments in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review". Cognitive Computation. doi:10.1007/s12559-021-09940-8. ISSN 1866-9964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-021-09940-8. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- {Egger, Helen L.; Dawson, Geraldine; Hashemi, Jordan; Carpenter, Kimberly L. H.; Espinosa, Steven; Campbell, Kathleen; Brotkin, Samuel; Schaich-Borg, Jana et al. (2018-06-01). "Automatic emotion and attention analysis of young children at home: a ResearchKit autism feasibility study". npj Digital Medicine 1 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1038/s41746-018-0024-6. ISSN 2398-6352. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-018-0024-6. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- "Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 59 (1): 27–43, ix–x. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.10.003. PMID 22284791. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.pcl.2011.10.003

- "Rubella". Lancet 385 (9984): 2297–2307. 7 January 2015. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60539-0. PMID 25576992. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4514442

- "Opening a window to the autistic brain". PLOS Biol 2 (8): E267. 2004. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020267. PMID 15314667. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=509312

- "Evidence Base Update for Autism Spectrum Disorder". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 44 (6): 897–922. 2 November 2015. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1077448. PMID 26430947. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F15374416.2015.1077448

- "Meta-analysis of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention for children with autism". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 38 (3): 439–450. May 2009. doi:10.1080/15374410902851739. PMID 19437303. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F15374410902851739

- "Behavioural and developmental interventions for autism spectrum disorder: a clinical systematic review". PLOS ONE 3 (11): e3755. 2008. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003755. PMID 19015734. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.3755O. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2582449

- "Systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions for autism: an umbrella review". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 51 (2): 95–104. February 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03211.x. PMID 19191842. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1469-8749.2008.03211.x

- "Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 37 (1): 8–38. January 2008. doi:10.1080/15374410701817808. PMID 18444052. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2943764

- "Systematic review of early intensive behavioral interventions for children with autism". American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 114 (1): 23–41. January 2009. doi:10.1352/2009.114:23-41. PMID 19143460. https://dx.doi.org/10.1352%2F2009.114%3A23-41

- "An update on pharmacotherapy for autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents". Current Opinion in Psychiatry 28 (2): 91–101. March 2015. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000132. PMID 25602248. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FYCO.0000000000000132

- "Interventions to address health outcomes among autistic adults: A systematic review". Autism 24 (6): 1345–1359. August 2020. doi:10.1177/1362361320913664. PMID 32390461. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7787674

- "Early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5 (10): CD009260. May 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009260.pub3. PMID 29742275. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6494600

- "Outcome of comprehensive psycho-educational interventions for young children with autism". Res Dev Disabil 30 (1): 158–178. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.02.003. PMID 18385012. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ridd.2008.02.003

- "Effects of a model treatment approach on adults with autism". J Autism Dev Disord 33 (2): 131–140. 2003. doi:10.1023/A:1022931224934. PMID 12757352. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FA%3A1022931224934

- "Inclusion of Learners with Autism Spectrum Disorders in General Education Settings". Topics in Language Disorders 23 (2): 116–133. 2003. doi:10.1097/00011363-200304000-00005. http://www.nursingcenter.com/pdf.asp?AID=520301.

- "Autism Spectrum Disorder: Primary Care Principles". American Family Physician 94 (12): 972–979. December 2016. PMID 28075089. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28075089

- "Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 17 (3): 348–355. June 2007. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.17303. PMID 17630868. https://dx.doi.org/10.1089%2Fcap.2006.17303

- "Pharmacologic treatments for the behavioral symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders across the lifespan". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 14 (3): 263–279. September 2012. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.3/cdoyle. PMID 23226952. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3513681

- "Pharmacological treatment options for autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents". Harvard Review of Psychiatry 16 (2): 97–112. 2008. doi:10.1080/10673220802075852. PMID 18415882. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F10673220802075852