Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hassan Ragab El-Ramady | -- | 3073 | 2022-09-21 10:16:08 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -3 word(s) | 3070 | 2022-09-21 10:31:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

El-Ramady, H.; Brevik, E.C.; Fawzy, Z.F.; Elsakhawy, T.; Omara, A.E.; Amer, M.; Faizy, S.E.; Abowaly, M.; El-Henawy, A.; Kiss, A.; et al. Nano-Restoration for Sustaining Soil Fertility. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27424 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

El-Ramady H, Brevik EC, Fawzy ZF, Elsakhawy T, Omara AE, Amer M, et al. Nano-Restoration for Sustaining Soil Fertility. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27424. Accessed February 07, 2026.

El-Ramady, Hassan, Eric C. Brevik, Zakaria F. Fawzy, Tamer Elsakhawy, Alaa El-Dein Omara, Megahed Amer, Salah E.-D. Faizy, Mohamed Abowaly, Ahmed El-Henawy, Attila Kiss, et al. "Nano-Restoration for Sustaining Soil Fertility" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27424 (accessed February 07, 2026).

El-Ramady, H., Brevik, E.C., Fawzy, Z.F., Elsakhawy, T., Omara, A.E., Amer, M., Faizy, S.E., Abowaly, M., El-Henawy, A., Kiss, A., Törős, G., Prokisch, J., & Ling, W. (2022, September 21). Nano-Restoration for Sustaining Soil Fertility. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27424

El-Ramady, Hassan, et al. "Nano-Restoration for Sustaining Soil Fertility." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 September, 2022.

Copy Citation

Soil is a real treasure that humans cannot live without. Therefore, it is very important to sustain and conserve soils to guarantee food, fiber, fuel, and other human necessities. Healthy or high-quality soils that include adequate fertility, diverse ecosystems, and good physical properties are important to allow soil to produce healthy food in support of human health. When a soil suffers from degradation, the soil’s productivity decreases. Soil restoration refers to the reversal of degradational processes.

soil–plant nexus

soil degradation

soil conservation

waterlogged soil

salt-affected soil

1. Introduction

The soil system represents one of the main natural resources that supplies human needs for food, feed, fiber, fuel, and more [1][2]. Agroecosystems are crucial to guaranteeing human life because of the interactions among their compartments, which include soil, water, plants, microbes, humans, and animals [3]. Thus, many studies have focused on the role of agroecosystems in sustaining and restoring soil fertility, or the ability of the soil to provide needed nutrients to crops. The loss of soil fertility may result from degradational processes such as pollution of the soil–plant–water system [4], alkalinity and salinity [5], or antagonisms from other nutrients or elements that may be added during agricultural management [6]. One of the most active portions of an agroecosystem is the soil microbes. These microbes have crucial impacts, mainly in the rhizosphere, through significant reactions in soil–plant–microbial activity, which may enhance soil fertility [7]. Several reactions occur in the rhizosphere that involve the release of root exudates or plant metabolites to support the soil microbial community for transformation of nutrients [7]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to build soil organic content and microbial communities to achieve both soil fertility and sustainable agriculture [3][7][8][9][10].

A number of studies have highlighted factors that are associated with interactions among different compartments of the agroecosystem. The relationship among different nexuses and their link to soil and water has been widely investigated, such the systems of soil–water–climate change [11], water–land–energy–food [12][13], soil–food–environment–health [14], sustainable water–energy–environment [15], water–food–energy–climate [16], water–energy–waste [17], water–energy–food [18][19][20], water–food–land–ecosystem [21], water–energy–carbon [22], soil health–human health [23], and soil–water–plant–human [24]. Photographic or pictorial articles can be highly effective at communicating these complex nexuses [2]. This has led to several recent articles that have used illustrations and/or photographs to highlight topics such as smart agriculture [25], soil and humans [26], management of salt-affected soils [27], the comparison between higher plants and mushrooms [28], nano-farming [29], nano-grafting [30], and the soil–water–plant–human nexus [24].

2. Soil and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

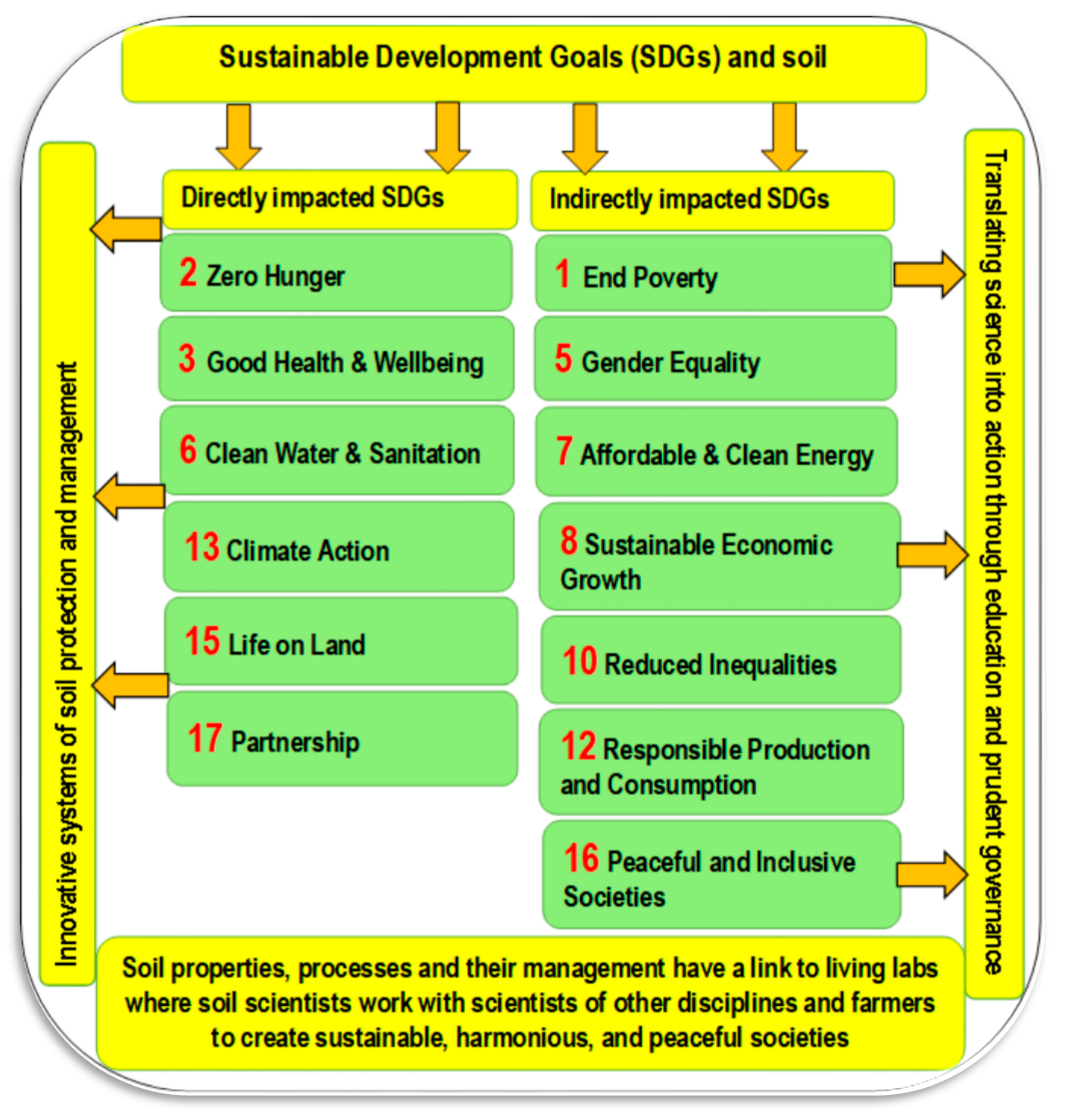

The need to feed around 10 billion people by 2050 represents a great challenge for the entire world. This necessitates an increase in agricultural production of ~70% by 2050 [31]. Soil is a major factor in this production. Soil is central to many of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [32], as seen in Figure 1. The SDGs were announced by the United Nations and have direct and indirect impacts on managing soil functions [33]. Many of the SDGs can be directly (SDGs 2, 3, 6, 13, 15, and 17) or indirectly (SDGs 1, 5, 6, 8, 10, and 16) affected by soil quality and management [34].

Figure 1. Sustainable Development Goals and their relationships with soil management (Sources: Lal et al. [32]).

Thus, the quality and persistence of soil functions and their achievement for these goals mainly rely on soil health [35]. In line with these goals, there is an urgent need for continuous support of soil ecosystem services [33]. Any progress in achieving the SDGs requires sustainable management of soils, because many SDGs are directly influenced by the properties and processes of soils [32].

Soil restoration is a crucial approach to achieve the goal of zero hunger [36][37] (Figure 2). Soil restoration is a process in which the reduced soil fertility or soil health/quality of degraded soil is reversed through management practices to restore ecosystem functions and services. The main things that need to be restored include (1) physical degradation (e.g., compaction, erosion, sealing, loss of structure), (2) chemical degradation (e.g., salt-affected soils, pollution, acidification), (3) biological degradation (loss of soil biodiversity, low soil organic matter), and (4) ecological degradation (loss of nutrients and carbon, inhibited in the denaturing of pollutants) [31]. There is a strong relationship between soil fertility and its management (from one side) and SDG 2 (zero hunger), from the other. Zero hunger is strongly connected to global issues represented in food security, malnutrition, and sustainable agriculture. These issues mainly depend on soil fertility and its management through the ecological management of nutrients, which is needed to overcome environmental obstacles such as soil degradation, water pollution, and climate change [38].

3. Restoration of Degraded Soils

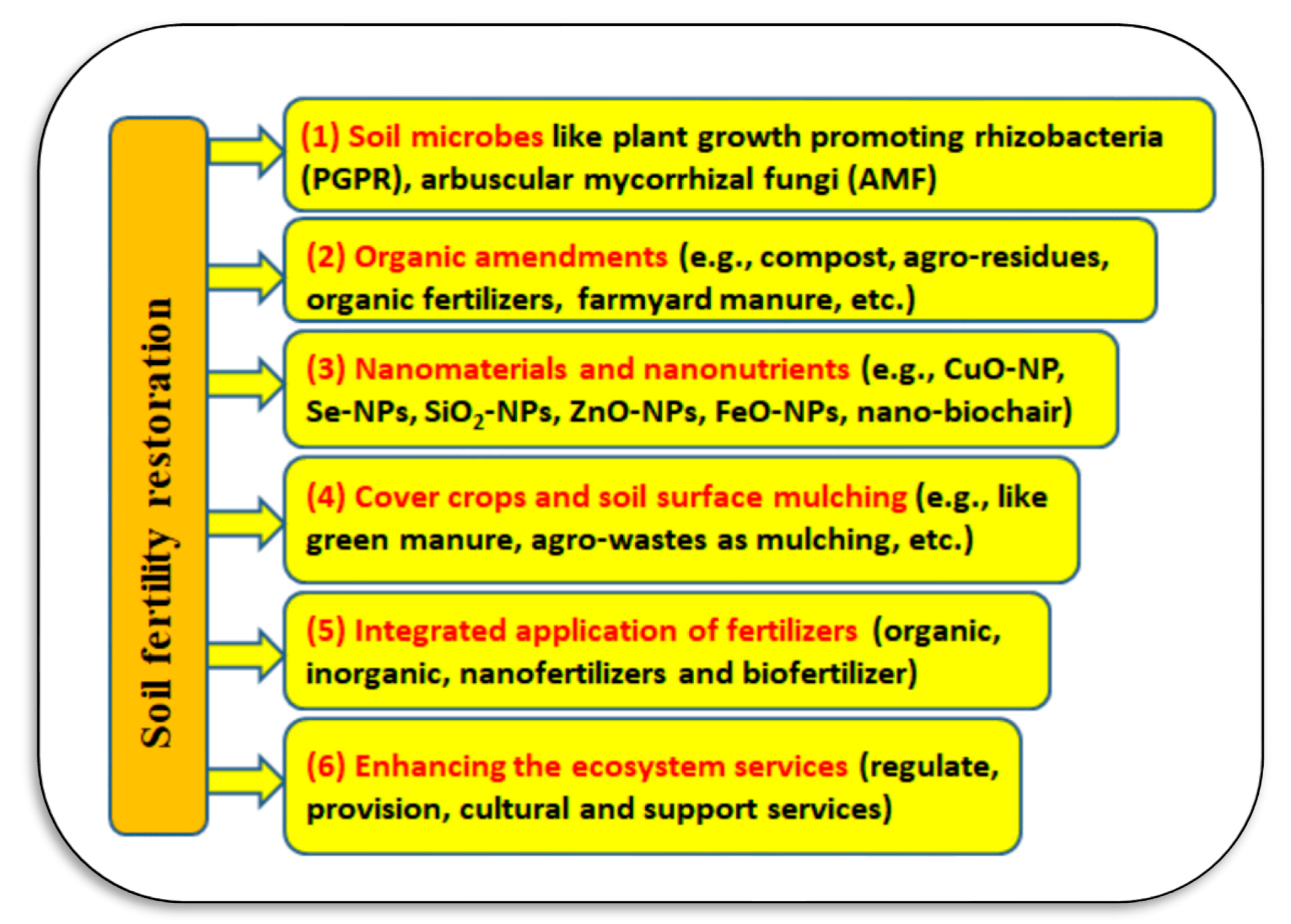

Soil degradation can be defined as “a change in the soil health status resulting in a diminished capacity of the ecosystem to provide goods and services for its beneficiaries” [40]. Soil degradation includes losses in soil biodiversity, productivity, and fertility. The main causes of soil degradation are pollution resulting from industrial, agricultural, and commercial activities, loss of arable lands due to overgrazing, urban sprawl/expansion, climatic changes, and unsustainable agricultural practices. Restoration of soil fertility can be achieved through sustainable management of degraded lands, such as climate change mitigation through the cultivation of bioenergy crops, production of animal proteins through intensive rotational grazing, and restoration of biodiversity by converting degraded croplands into conservation plantings [38]. Soil fertility can be restored by applying different approaches as presented in Figure 3, which may include using plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, applying organic amendments, inorganic fertilization, nanomaterials and nano-nutrients, cover crops and soil surface mulching, preventing hardening or compaction of the soil, integrated application of fertilizers to include organic, inorganic and biofertilizer, perennialization of cropping systems, and enhancing the sources of ecosystem services [38][39]. Several kinds of degraded soils are well-known, such as sandy soils in arid regions, waterlogged soils, polluted soils, mined soils, and salt-affected soils. In the following sub-sections, a certain concern will focus on two common types of degraded soils (i.e., saline sandy and saline–sodic soils).

3.1. Saline Sandy Soils

Restoration of saline sandy soils especially in arid regions depends on the main problem of these soils (i.e., salinity level in soil, low content of organic matter and nutrients, low ability to hold water). Applying the organic amendments like compost or organic fertilizers or green manure are the most common practices in sandy soils (Figure 4). Under water stress conditions, foliar application using salicylic acid (150 mg L−1), and ascorbic acid (100 mg L−1) can support the productivity of olive trees grown in Matrouh, Egypt [41]. The integrated inoculation of pearl millet by mycorrhizae fungi, with combined application of humic acid (38.4 kg ha−1) and phosphoric acid (1.5 mL L−1) improved the availability of nutrient status of sandy calcareous soil in Mariout, southwest of Alexandria, Egypt [42]. Integrated management of K-additives (apply Amphora extract of algae, biochar, and compost) to improve Zucchini productivity grown on sandy soil [43]. The combined amending sandy soils with mixed organic and mineral as N-sources and irradiating seeds of faba bean to increase the crop productivity was reported by Farid et al. [44]. The microbial mixtures (Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas flourescens, Pleurotus ostreatus, and mycorrhizeen®) modified soil physio-chemical properties and its fertility, and consequently increased productivity of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. in sandy soil [45].

Figure 4. Cultivation of sandy soils is a great challenge facing the arid and semi-arid regions because of low fertility and low ability to hold water. These photos represent cultivation of sandy soil with different horticultural crops in Egypt, including citrus, grapes (higher photo left from saline sandy and right), mango (middle photos, which represent saline sandy soils), and banana (lower photo left). Photos by El-Ramady.

Soil microbes (biofertilizers) can increase soil fertility through enhancing solubility and uptake of nutrients in soil by cultivated plants, and then increase productivity and its yield [46]. The tripartite interaction among soil–plant–microbes is very important for soil fertility and sustainable agriculture. The reason represents in the nature of this relationship between plant and microbes, which lead to converting the unavailable nutrients in soil into available and uptakeable by plants [47]. Besides the acquisition of nutrients and due to the beneficial activities of soil–nutrient–microbe–plant interactions, soil microbes can also inhibit plant pathogens and induce plant defense response [47]. Under the circular economy, using agri-based organic wastes in producing bio-organic fertilizer and compost via soil beneficial microbes at the farm level are a crucial approach for a sustainable design of new cropping systems, and for increasing soil natural suppressiveness to soil-borne plant pathogens [48].

3.2. Saline–Sodic Soils

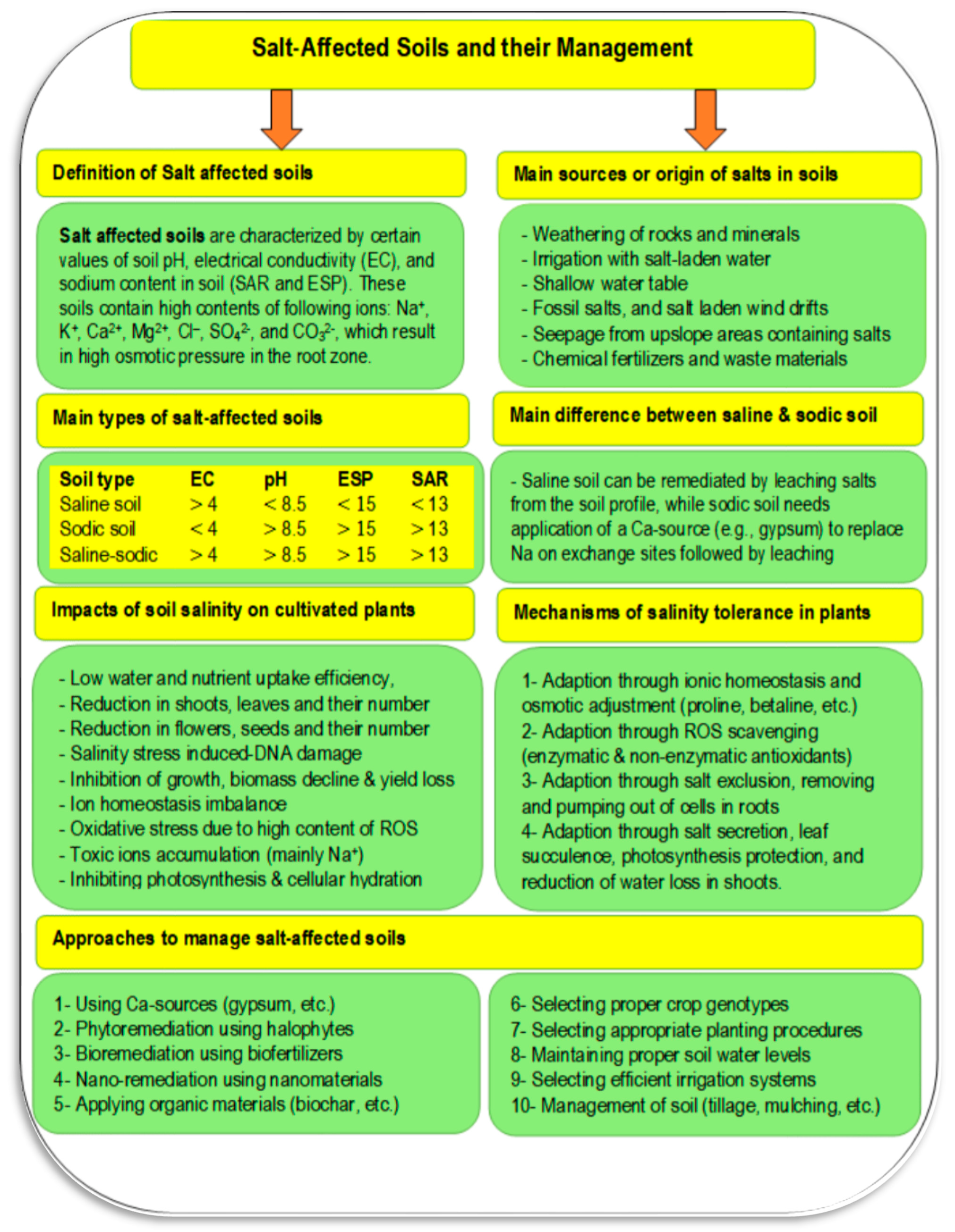

Salt-affected soils are a common problem. Salts are a major constraint for high crop productivity on about 1125 million hectares globally and are especially problematic in arid and semi-arid regions [49]. These soils are formed by both anthropogenic activities and natural causes. Natural causes include fossil salt deposits, the weathering of salty parent materials, deposition of salts by water or wind, and the tidal flow of sea water or groundwater inflow in coastal lands. Anthropogenic activities that lead to degradation through salinization may include irrigation with saline water, poor drainage and irrigation management, replacement of perennial vegetation with annual crops (which changes water relationships), seepage of canal water, over-extraction of groundwater, over-use of agrochemicals, and using waste effluents in irrigation systems [50][51]. The type of soil salinity is indicated by measures including electrical conductivity (EC), soil pH, and soil sodium content. Sodium content is given as either sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), a measure of how much sodium is on the soil exchange sites relative to calcium and magnesium, and exchangeable sodium percent (ESP), a measure of how much of the total cation exchange sites are occupied by sodium. Salt affected soils have distinguishing features, such as the accumulation of salts on the soil surface, poor structure due to dispersion of clays, and others, as presented in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 6. Some common features of saline-alkaline soils at the experimental farm of Kafrelsheikh Uni. (Egypt), which represent in sabkha on the soil surface and growing the purslane plants (the first higher 2 photos beside the middle photo left), the accumulation of salts during rice growing in saline soil in the middle photo right, and the lower photos (left) general view to saline soil during cultivating lettuce under drip irrigation and deep cracks due to heavy clay content (the lower right photo). Photos by El-Ramady.

Figure 7. Production of horticultural crops under arid climatic zones and salinity stress in salt-affected soils at the experimental farm of Kafrelsheikh University (Egypt). Many crops physiological and nutritional problems (mainly nutrient imbalances, dehydration, disease pressure due to decreased resistance) can be seen on the cultivated crops from top to bottom; lettuce, sugar-apple tree (top photos), persimmon (the middle photos), and citrus (lower photos). Photos by El-Ramady.

Figure 8. Salt-affected soils have general characteristics, including the accumulation of salts on the surface of the soil, missing plants due to high soil salinity in the field or under greenhouse conditions, high water table content due to poor drainage, especially in traditional greenhouses, and high temperature, which increases evaporation from the soil surface and thus accumulation of salts on the soil surface. Photos by El-Ramady.

Salt-affected soils can be classified geographically into coastal and inland salt-affected soils based on the Indian approach. Coastal saline soils are classified as saline soils and acid–saline soils based mainly on soil pH and EC, whereas inland salt-affected soils are classified into saline, sodic, and saline–sodic based on the values of soil pH, EC, and SAR or ESP [53]. The major areas that have salt-affected soils globally include Asia (mainly China, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan), Africa (mainly in the north of Africa including Egypt, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia), North and Central of America (e.g., the western USA and Canada, and Mexico), South America (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Paraguay), Europe (mainly in Hungary, France, and Romania), and Australia [53]. The main features of saline/alkaline soils may include the growth of halophyte plants like purslane, the accumulation of salts on the soil surface, nutrient deficiency due to nutrient imbalances, plant dehydration, disease pressure due to decreased resistance, etc.

Salt-affected soils have several impacts on both soil and cultivated plants. Salinity stress is a complex process that negatively influences nearly all of a plant’s biochemical and physiological processes. As a result, crop productivity is decreased due to inhibition of plant growth, reduced biomass, and its yield, decline in shoots, leaves, flowers, and seeds, low water and nutrient uptake efficiency, induced-DNA damage, oxidative stress due to a high content of reactive oxygen species (ROS), inhibition of photosynthesis and cellular hydration, and accumulation of toxic ions, mainly Na+ [52][53][56][57][58][59]. Impacts on the soil itself include loss of structure, dispersion of organic matter, antagonism of nutrient update, increased soil erosion rate (due to high soil dispersibility and decrease shear stress), increased flooding rate (due to higher runoff because of low soil permeability), ecological imbalances (due to changes in vegetation including halophytes, bushes, mesophytes, and trees), and may cause problems for human health because of frequent malaria outbreak and other diseases [53][60][61]. Under salinized environments, many mechanisms could be adapted to make plants more tolerant to salinity, including (1) adaption through ionic homeostasis and osmotic adjustment (proline, betaine, etc.), (2) adaption through ROS scavenging (enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants), (3) adaption through salt exclusion, removing and pumping salt out of root cells, and (4) adaption through salt secretion, leaf succulence, photosynthesis protection, and reduction of water loss in shoots [55].

Salt-affected soils can negatively affect crop productivity causing huge losses in both yield and its economic value. Thus, proper management strategies must be adopted to reduce stressful conditions on cultivated crops and to protect the soils from the devastating and deleterious impacts of this stress using combinations of the following approaches (Table 1):

-

Application of Ca-sources like gypsum [53],

-

Application of biofertilizers [64],

-

Nano-remediation using nanomaterials [65],

-

Using integrated fertilization [70],

-

Maintaining soil water level by using proper fertilization/irrigation [71],

-

Selecting efficient irrigation systems [72], and

-

Soil management through techniques like tillage and mulching [73].

It is essential to utilize sustainable approaches to reduce the deleterious impacts of salinity stress, as reported by several published articles such as El Sabagh et al. [74]; Farid et al. [75]; Leal et al. [76]; Naz et al. [77]; Khan et al. [78] (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Table 1. Some published studies on managing salt-affected soils using different nanomaterials and biofertilizers.

| Used Nanomaterials/Amendment | Cultivated Plant | Properties of Used Soil | Main Findings | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Applied nanomaterials | ||||

| Nano-Zn, nano-Si (30, 25 nm and 50, 2.5 mg L−1, resp.) | Rice (Oryza sativa, L.), var. Giza 178 | Clayey, EC = 7.6 dS m−1, SAR = 14, ESP = 22.5% | Improved saline sodic soil by integrated management of both nano-Zn, and nano-Si in addition to using straw-filled ditches | [79] |

| Nano-ZnO at levels of 1 and 2 g·L−1 (40–50 nm) | Faba bean (Vicia faba L.), var. Sakha 1 | Clayey, pH = 8.43, EC = 7.48 dS m−1, SAR = 16.2, ESP = 18.6 | Application of nano-ZnO compost and S was integrated to reclaim saline–sodic soils | [80] |

| Green nano-silica (150 and 300 mg L−1) | Banana (Musa spp.) | Sandy irrigated with groundwater (EC = 4.12 dS m−1) | Green nano-silica improved the productivity and quality in sandy soil with saline irrigation | [81] |

| MgO-NP at 50 and 100 µg ml−1 as foliar application | Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) cv. Beauregard | Sandy loam, EC = 7.56 dS m−1, pH = 7.65, ESP = 10.66% | Co-applied effective micro-organisms and/or MgO-NPs improved plant tolerant to osmotic stress by increase osmolytes level, K+ content | [65] |

| Nanoparticles (Si-Zn-NPs) and plant growth-promoting microbes (PGPMs) | Soybean (Glycine max L.) cv. Giza 111 | Clayey, pH = 8.23, EC = 5.52 dS m−1, ESP = 16% | PGPMs and nanoparticles (Si-Zn-NPs) promoted soybean productivity, and seed quality under water deficit stress | [82] |

| Foliar NPs-Si (12.5 mg L−1) and bio-Se-NPs (6.25 mg L−1) | Rice (Oryza sativa L.), Giza 177 and Giza 178 | Clayey, pH = 8.20, EC = 7.20 dS m−1, SOM = 1.62% | Applied nano-nutrients (NPs-Si and NPs-Se) improved the yield components and mitigated harmful salinity stress | [83] |

| II. Applied biofertilizers/organic fertilizers | ||||

| Extracts of moringa leaves, licorice roots, ginger (2.0%) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), cv. Misr 1 | Clayey, pH = 8.13, EC = 13.20 dS m−1, ESP = 15.08% | Proline and enzymatic antioxidants (CAT, SOD) after treating with vermicompost and sprayed with moringa extract | [84] |

| PGPR, some strains of both Rhizobium and Bacillus | Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.), cv. 716 | Clayey, pH = 8.24, EC = 5.52 dS m−1, SOM = 1.19%, ESP = 20% | Foliar PGPR and potassium silicate maintain soil quality and increased productivity of plants irrigated with saline water (3.5 dS m−1) | [85] |

| PGPR, namely some strains of Azospirillum and Bacillus | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), cv. Misr 1 | Clay loam, pH = 8.58, EC = 9.09 dS m−1, SOM = 1.48%, ESP = 18% | Collaborative impact of PGPR and compost on soil properties, and physiological–biochemical attributes of wheat under water deficit stress | [86] |

| Bacterial inoculation (plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria) | Maize (Zea mays L.) cv. HSC 10 | Clayey, pH = 8.22, EC = 7.33 dS m−1, ESP = 21.27% | Phosphor-gypsum and PGPR are effective approach for ameliorating the negative stress of salinity on maize plants | [87] |

| Foliar spray of folic acid (FA), ascorbic acid (AA), and salicylic acid (SA) | Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cv. Spunta | Loam, pH = 7.71, EC = 7.14 dS m−1, SOM = 0.79% | Foliar AA (200 mg L−1) was most effective in enhancing plant tolerance to salinity stress | [88] |

| Gypsum and mycorrhizal fungi inoculation (AMF) | Wheat (T. aestivum L.), cv. Sakha 94; maize (Z. mays L.), cv. Hybrid 368 | Heavy clay, pH = 8.32, EC = 7.09 dS m−1, ESP = 19.35%, SOM = 1.16% | Combination of applied gypsum and AMF inoculation was an effective approach to ameliorate and alleviate the hazardous effects of soil salinity and sodicity on cultivated plants | [89] |

| PGPR (Azospirillum brasilense and Bacillus circulans); potassium silicate | Wheat (T. aestivum L.), cv. Misr 1, Gemmeza 12, and Sakha 95 | Clayey texture, pH = 8.28, EC = 7.71 dS m−1, SOM = 1.75% | Combined application activated soil enzymes (i.e., urease and dehydrogenase); boosted soil microbial activity; enhanced plant growth at studied stress | [90] |

| Biochar (husks of rice and maize) and foliar applied potassium humate | Onion (Allium cepa L.), cv. Giza 20 | Clay loam, pH = 8.35, EC = 11.14 dS m−1, SOM = 1.51% | Dual application of biochar and K-humate was sustainable, an effective, eco-friendly strategy under water stress | [91] |

Figure 9. Saline–sodic soils in Kafrelsheikh, Egypt, could be managed using the application of gypsum (seen as the white spots on the soils in the photos). Cleaning the agricultural canals and/or drains is common at the experimental farm of Kafrelsheikh University to avoid harmful impact of Na in such soils, which is necessary to provide good drainage and reduce anthropogenically-induced salinization of the soils. Photos by El-Ramady.

Figure 10. Cultivation of paddy rice is very important in managing salt-affected soils in the Kafr El-Sheikh region (Egypt), which depends on the flooding irrigation to overcome soil salinity in this area. Photos by El-Ramady.

References

- Brevik, E.C.; Pereg, L.; Pereira, P.; Steffan, J.J.; Burgess, L.C.; Gedeon, C. Shelter, clothing, and fuel: Often overlooked links between soils, ecosystem services, and human health. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 134–142.

- El-Ramady, H.; Hajdú, P.; Törős, G.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Kiss, A.; Abdalla, N.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Elsakhawy, T.; Elbasiouny, H.; et al. Plant Nutrition for Human Health: A Pictorial Review on Plant Bioactive Compounds for Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8329.

- Shayanthan, A.; Ordoñez, P.A.C.; Oresnik, I.J. The Role of Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynCom) in Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 896307.

- Gonçalves, R.G.D.M.; dos Santos, C.A.; Breda, F.A.D.F.; Lima, E.S.A.; Carmo, M.G.F.D.; Souza, C.D.C.B.D.; Sobrinho, N.M.B.D.A. Cadmium and lead transfer factors to kale plants (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) grown in mountain agroecosystem and its risk to human health. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 366.

- Zhang, J.; Dolfing, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, R.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Feng, Y. Beyond the snapshot: Identification of the timeless, enduring indicator microbiome informing soil fertility and crop production in alkaline soils. Environ. Microbiome 2022, 17, 25.

- Pereg, L.; Steffan, J.J.; Gedeon, C.; Thomas, P.; Brevik, E.C. Medical Geology of Soil Ecology. In Practical Applications of Medical Geology; Siege, M., Selinus, O., Finkelman, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 343–401.

- Yadav, R.H. Soil-plant-microbial interactions for soil fertility management and sustainable agriculture. In Microbes in Land Use Change Management; Singh, J.S., Tiwari, S., Singh, C., Singh, A.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 341–362.

- Page, K.L.; Dang, Y.P.; Dalal, R.C. The Ability of Conservation Agriculture to Conserve Soil Organic Carbon and the Subsequent Impact on Soil Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties and Yield. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 31.

- Castellini, M.; Diacono, M.; Gattullo, C.; Stellacci, A. Sustainable Agriculture and Soil Conservation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4146.

- Scagliola, M.; Valentinuzzi, F.; Mimmo, T.; Cesco, S.; Crecchio, C.; Pii, Y. Bioinoculants as Promising Complement of Chemical Fertilizers for a More Sustainable Agricultural Practice. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 622169.

- Koriem, M.; Gaheen, S.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J.; Brevik, E. Global Soil Science Education to Address the Soil—Water-Climate Change Nexus. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 27–39.

- Psomas, A.; Vryzidis, I.; Spyridakos, A.; Mimikou, M. MCDA approach for agricultural water management in the context of water–energy–land–food nexus. Oper. Res. 2021, 21, 689–723.

- Wolde, Z.; Wei, W.; Ketema, H.; Yirsaw, E.; Temesegn, H. Indicators of Land, Water, Energy and Food (LWEF) Nexus Resource Drivers: A Perspective on Environmental Degradation in the Gidabo Watershed, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5181.

- Gu, B.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y.; Vitousek, P.; Zhu, Y.-G. Soil-Food-Environment-Health Nexus for Sustainable Development. Research 2021, 2021, 9804807.

- Wan, R.; Ni, M. Sustainable water–energy–environment nexus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 40049–40052.

- Adebiyi, J.A.; Olabisi, L.S.; Liu, L.; Jordan, D. Water–food–energy–climate nexus and technology productivity: A Nigerian case study of organic leafy vegetable production. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 6128–6147.

- Misrol, M.A.; Alwi, S.R.W.; Lim, J.S.; Manan, Z.A. Optimization of energy-water-waste nexus at district level: A techno-economic approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111637.

- Bian, Z.; Liu, D. A Comprehensive Review on Types, Methods and Different Regions Related to Water–Energy–Food Nexus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8276.

- de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.; Berchin, I.I.; Garcia, J.; da Silva Neiva, S.; Jonck, A.V.; Faraco, R.A.; de Amorim, W.S.; Ribeiro, J.M.P. A literature-based study on the water-energy-food nexus for sustainable development. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 95–116.

- Yuan, M.-H.; Lo, S.-L. Principles of food-energy-water nexus governance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111937.

- Shi, X.; Matsui, T.; Machimura, T.; Haga, C.; Hu, A.; Gan, X. Impact of urbanization on the food–water–land–ecosystem nexus: A study of Shenzhen, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152138.

- Yu, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Dong, S.; Zhao, W.; Tran, L.-S.P.; Sun, Y.; et al. Effects of agricultural activities on energy-carbon-water nexus of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129995.

- Rekik, F.; van Es, H.M. The soil health–human health nexus: Mineral thresholds, interlinkages and rice systems in Jhar-khand, India. In Advances in Agronomy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021.

- Brevik, E.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Elsakhawy, T.A.; Amer, M.M.; Abdalla, Z.F.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J. The Soil-Water-Plant-Human Nexus: A Call for Photographic Review Articles. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 117–131.

- Abdalla, Z.F.; El-Ramady, H. Applications and Challenges of Smart Farming for Developing Sustainable Agriculture. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 81–90.

- Elramady, H.; Brevik, E.C.; Elsakhawy, T.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Amer, M.M.; Abowaly, M.; El-Henawy, A.; Prokisch, J. Soil and Humans: A Comparative and A Pictorial Mini-Review. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 62, 101–115.

- El-Ramady, H.; Faizy, S.; Amer, M.M.; Elsakhawy, T.A.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Eid, Y.; Brevik, E. Management of Salt-Affected Soils: A Photographic Mini-Review. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 61–79.

- El-Ramady, H.; Törős, G.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Hajdú, P.; El-Mahrouk, M.E.; Abdalla, N.; Prokisch, J. A Comparative Photographic Review on Higher Plants and Macro-Fungi: A Soil Restoration for Sustainable Production of Food and Energy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7104.

- Abdalla, Z.F.; El-Ramady, H.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Elsakhawy, T.A.; Bayoumi, Y.; Shalaby, T.; Prokisch, J. From Farm-to-Fork: A pictorial Mini Review on Nano-Farming of Vegetables. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 149–163.

- Bayoumi, Y.; Shalaby, T.; Abdalla, Z.F.; Shedeed, S.H.; Abdelbaset, N.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J. Grafting of Vegetable Crops in the Era of Nanotechnology: A photographic Mini Review. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 133–148.

- Lal, R. Restoring Soil Quality to Mitigate Soil Degradation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5875–5895.

- Lal, R.; Bouma, J.; Brevik, E.; Dawson, L.; Field, D.J.; Glaser, B.; Hatano, R.; Hartemink, A.E.; Kosaki, T.; Lascelles, B.; et al. Soils and sustainable development goals of the United Nations: An International Union of Soil Sciences perspective. Geoderma Reg. 2021, 25, e00398.

- Löbmann, M.T.; Maring, L.; Prokop, G.; Brils, J.; Bender, J.; Bispo, A.; Helming, K. Systems knowledge for sustainable soil and land management. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153389.

- Elsakhawy, T.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Abowaly, M.; El-Ramady, H.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Törős, G.; Hajdú, P.; Prokisch, J. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms: A Crucial Dimension for Sustainable Soil Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4328.

- Lal, R.; Horn, R.; Kosaki, T. Soil and Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.schweizerbart.de/publications/detail/isbn/9783510654253/Soil_and_Sustainable_Development_Goals (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Vogliano, C.; Murray, L.; Coad, J.; Wham, C.; Maelaua, J.; Kafa, R.; Burlingame, B. Progress towards SDG 2: Zero hunger in Melanesia—A state of data scoping review. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 29, 100519.

- Pingali, P.; Plavšić, M. Hunger and environmental goals for Asia: Synergies and trade-offs among the SDGs. Environ. Chall. 2022, 7, 100491.

- Mosier, S.; Córdova, S.C.; Robertson, G.P. Restoring Soil Fertility on Degraded Lands to Meet Food, Fuel, and Climate Security Needs via Perennialization. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 706142.

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, J.; Gonzalez-Ollauri, A.; Yang, Y.; Chen, F. Soil microbes-mediated enzymes promoted the secondary succession in post-mining plantations on the Loess Plateau, China. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2022, 1–15.

- Pereira, P.; Brevik, E.C.; Muñoz-Rojas, M.; Miller, B.A.; Smetanova, A.; Depellegrin, D.; Misiune, I.; Novara, A.; Cerdà, A. Soil Mapping and Processes Modeling for Sustainable Land Management. In Soil Mapping and Process Modeling for Sustainable Land Use Management; Pereira, P., Brevik, E., Muñoz-Rojas, M., Miller, B., Smetanova, A., Depellegrin, D., Misiune, I., Novara, A., Cerda, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 29–60.

- El Refaey, A.; Mohamed, Y.I.; El-Shazly, S.M.; El Salam, A.A.A. Effect of Salicylic and Ascorbic Acids Foliar Application on Picual Olive Trees Growth under Water Stress Condition. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 62, 1–16.

- Habib, A. Response of Pearl Millet to Fertilization by Mineral Phosphorus, Humic Acid and Mycorrhiza under Calcareous Soil Conditions. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 61, 399–411.

- Tolba, M.; Farid, I.M.; Siam, H.; Abbas, M.H.; Mohamed, I.; Mahmoud, S.; El-Sayed, A.E.-K. Integrated management of K -additives to improve the productivity of zucchini plants grown on a poor fertile sandy soil. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 61, 255–365.

- Farid, I.M.; El-Nabarawy, A.; Abbas, M.H.; Morsy, A.; Afifi, M.; Abbas, H.; Hekal, M. Implications of seed irradiation with γ-rays on the growth parameters and grain yield of faba bean. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 61, 175–186.

- Gaafar, D.E.S.M.; Baka, Z.A.M.; Abou-Dobara, M.I.; Shehata, H.S.; El-Tapey, H.M.A. Microbial impact on growth and yield of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. and sandy soil fertility. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 61, 259–274.

- Vishwakarma, K.; Kumar, N.; Shandilya, C.; Mohapatra, S.; Bhayana, S.; Varma, A. Revisiting Plant–Microbe Interactions and Microbial Consortia Application for Enhancing Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 560406.

- Das, P.P.; Singh, K.R.; Nagpure, G.; Mansoori, A.; Singh, R.P.; Ghazi, I.A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, J. Plant-soil-microbes: A tripartite interaction for nutrient acquisition and better plant growth for sustainable agricultural practices. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113821.

- De Corato, U. Effect of value-added organic co-products from four industrial chains on functioning of plant disease suppressive soil and their potentiality to enhance soil quality: A review from the perspective of a circular economy. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104221.

- Hossain, M.S. Present scenario of global salt affected soils, its management and importance of salinity research. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 1, 1–3.

- Kumar, P.; Sharma, P.K. Soil Salinity and Food Security in India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 174.

- Rani, A.; Kumar, N.; Sinha, N.K.; Kumar, J. Identification of salt-affected soils using remote sensing data through random forest technique: A case study from India. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 381.

- Otlewska, A.; Migliore, M.; Dybka-Stępień, K.; Manfredini, A.; Struszczyk-Świta, K.; Napoli, R.; Białkowska, A.; Canfora, L.; Pinzari, F. When Salt Meddles Between Plant, Soil, and Microorganisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 553087.

- Chhabra, R. Salt-Affected Soils and Marginal Waters Global Perspectives and Sustainable Management; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–48.

- Stavi, I.; Thevs, N.; Priori, S. Soil Salinity and Sodicity in Drylands: A Review of Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Restoration Measures. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 712831.

- Guo, J.; Shan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Han, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B. Mechanisms of Salt Tolerance and Molecular Breeding of Salt-Tolerant Ornamental Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 854116.

- Dustgeer, Z.; Seleiman, M.F.; Khan, I.; Chattha, M.U.; Ali, E.F.; Alhammad, B.A.; Jalal, R.S.; Refay, Y.; Hassan, M.U. Glycine-betaine induced salinity tolerance in maize by regulating the physiological attributes, antioxidant defense system and ionic homeostasis. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49, 12248.

- Mohanavelu, A.; Naganna, S.R.; Al-Ansari, N. Irrigation Induced Salinity and Sodicity Hazards on Soil and Groundwater: An Overview of Its Causes, Impacts and Mitigation Strategies. Agriculture 2021, 11, 983.

- Sultan, I.; Khan, I.; Chattha, M.U.; Hassan, M.U.; Barbanti, L.; Calone, R.; Ali, M.; Majid, S.; Ghani, M.A.; Batool, M.; et al. Improved salinity tolerance in early growth stage of maize through salicylic acid foliar application. Ital. J. Agron. 2021, 16, 1810.

- Monsur, M.B.; Datta, J.; Rohman, M.D.M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Hossain, A.; Islam, M.S. Salt-Induced Toxicity and Antioxidant Response in Oryza sativa: An Updated Review. In Managing Plant Production Under Changing Environmen; Hasanuzzaman, M., Ahammed, G.J., Nahar, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022.

- Kamran, M.; Parveen, A.; Ahmar, S.; Malik, Z.; Hussain, S.; Chattha, M.S.; Saleem, M.H.; Adil, M.; Heidari, P.; Chen, J.-T. An Overview of Hazardous Impacts of Soil Salinity in Crops, Tolerance Mechanisms, and Amelioration through Selenium Supplementation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 148.

- Seleiman, M.F.; Aslam, M.T.; Alhammad, B.A.; Hassan, M.U.; Maqbool, R.; Chattha, M.U.; Khan, I.; Gitari, H.I.; Uslu, O.S.; Rana, R.; et al. Salinity stress in wheat: Effects, mechanisms and management strategies. Phyton 2022, 91, 667–694.

- Munir, N.; Hanif, M.; Dias, D.A.; Abideen, Z. The role of halophytic nanoparticles towards the remediation of degraded and saline agricultural lands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 60383–60405.

- Song, U.; Kim, B.W.; Rim, H.; Bang, J.H. Phytoremediation of nanoparticle-contaminated soil using the halophyte plant species Suaeda glauca. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102626.

- Hussien, E.A.A.; Ahmed, B.M.; Elbaalawy, A.M. Efficiency of Azolla and Biochar Application on Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Productivity in Salt-Affected Soil. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 60, 277–288.

- El-Mageed, T.A.A.; Gyushi, M.A.H.; Hemida, K.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; El-Mageed, S.A.A.; Abdalla, H.; AbuQamar, S.F.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Abdelkhalik, A. Coapplication of Effective Microorganisms and Nanomagnesium Boosts the Agronomic, Physio-Biochemical, Osmolytes, and Antioxidants Defenses Against Salt Stress in Ipomoea batatas. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 883274.

- Gunarathne, V.; Senadeera, A.; Gunarathne, U.; Biswas, J.K.; Almaroai, Y.A.; Vithanage, M. Potential of biochar and organic amendments for reclamation of coastal acidic-salt affected soil. Biochar 2020, 2, 107–120.

- Yao, R.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Zhu, W.; Yin, C.; Wang, X.; Xie, W.; Zhang, X. Combined application of biochar and N fertilizer shifted nitrification rate and amoA gene abundance of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in salt-affected anthropogenic-alluvial soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 171, 104348.

- Das, S.; Christopher, J.; Apan, A.; Choudhury, M.R.; Chapman, S.; Menzies, N.W.; Dang, Y.P. UAV-Thermal imaging and agglomerative hierarchical clustering techniques to evaluate and rank physiological performance of wheat genotypes on sodic soil. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 173, 221–237.

- Islam, A.T.; Koedsuk, T.; Ullah, H.; Tisarum, R.; Jenweerawat, S.; Cha-Um, S.; Datta, A. Salt tolerance of hybrid baby corn genotypes in relation to growth, yield, physiological, and biochemical characters. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 147, 808–819.

- Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Tao, J.; Yao, R. Integrated application of inorganic fertilizer with fulvic acid for improving soil nutrient supply and nutrient use efficiency of winter wheat in a salt-affected soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 170, 104255.

- Yao, R.; Li, H.; Zhu, W.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, C.; Jing, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xie, W. Biochar and potassium humate shift the migration, transformation and redistribution of urea-N in salt-affected soil under drip fertigation: Soil column and incubation experiments. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 267–282.

- Devkota, K.P.; Devkota, M.; Rezaei, M.; Oosterbaan, R. Managing salinity for sustainable agricultural production in salt-affected soils of irrigated drylands. Agric. Syst. 2022, 198, 103390.

- Garcia-Franco, N.; Wiesmeier, M.; Hurtarte, L.C.C.; Fella, F.; Martínez-Mena, M.; Almagro, M.; Martínez, E.G.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Pruning residues incorporation and reduced tillage improve soil organic matter stabilization and structure of salt-affected soils in a semi-arid Citrus tree orchard. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105129.

- EL Sabagh, A.; Islam, M.S.; Skalicky, M.; Raza, M.A.; Singh, K.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, A.; Mahboob, W.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ratnasekera, D.; et al. Salinity Stress in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in the Changing Climate: Adaptation and Management Strategies. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 661932.

- Farid, I.; Hashem, A.N.; El-Aty, A.; Esraa, A.M.; Abbas, M.H.; Ali, M. Integrated approaches towards ameliorating a saline sodic soil and increasing the dry weight of barley plants grown thereon. Environ. Biodiv. Soil Secur. 2020, 4, 31–46.

- Leal, L.D.S.G.; Pessoa, L.G.M.; de Oliveira, J.P.; Santos, N.A.; Silva, L.F.D.S.; Júnior, G.B.; Freire, M.B.G.D.S.; de Souza, E.S. Do applications of soil conditioner mixtures improve the salt extraction ability of Atriplex nummularia at early growth stage? Int. J. Phytoremediation 2020, 22, 482–489.

- Naz, T.; Iqbal, M.M.; Tahir, M.; Hassan, M.M.; Rehmani, M.I.A.; Zafar, M.I.; Ghafoor, U.; Qazi, M.A.; EL Sabagh, A.; Sakran, M.I. Foliar Application of Potassium Mitigates Salinity Stress Conditions in Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) through Reducing NaCl Toxicity and Enhancing the Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 566.

- Khan, I.; Muhammad, A.; Chattha, M.U.; Skalicky, M.; Ayub, M.A.; Anwar, M.R.; Soufan, W.; Hassan, M.U.; Rahman, A.; Brestic, M.; et al. Mitigation of Salinity-Induced Oxidative Damage, Growth, and Yield Reduction in Fine Rice by Sugarcane Press Mud Application. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 840900.

- Kheir, A.M.S.; Abouelsoud, H.M.; Hafez, E.M.; Ali, O.A.M. Integrated effect of nano-Zn, nano-Si, and drainage using crop straw–filled ditches on saline sodic soil properties and rice productivity. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 471.

- El-Sharkawy, M.; El-Aziz, M.A.; Khalifa, T. Effect of nano-zinc application combined with sulfur and compost on saline-sodic soil characteristics and faba bean productivity. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1178.

- Ding, Z.; Zhao, F.; Zhu, Z.; Ali, E.F.; Shaheen, S.M.; Rinklebe, J.; Eissa, M.A. Green nanosilica enhanced the salt-tolerance defenses and yield of Williams banana: A field trial for using saline water in low fertile arid soil. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 197, 104843.

- Osman, H.; Gowayed, S.; Elbagory, M.; Omara, A.; El-Monem, A.; El-Razek, U.A.; Hafez, E. Interactive Impacts of Beneficial Microbes and Si-Zn Nanocomposite on Growth and Productivity of Soybean Subjected to Water Deficit under Salt-Affected Soil Conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 1396.

- Badawy, S.A.; Zayed, B.A.; Bassiouni, S.M.A.; Mahdi, A.H.A.; Majrashi, A.; Ali, E.F.; Seleiman, M.F. Influence of Nano Silicon and Nano Selenium on Root Characters, Growth, Ion Selectivity, Yield, and Yield Components of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) under Salinity Conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 1657.

- Awwad, E.A.; Mohamed, I.R.; El-Hameedb, A.A.; Zaghloul, E.A. The Co-Addition of Soil Organic Amendments and Natural Bio-Stimulants Improves the Production and Defenses of the Wheat Plant Grown under the Dual stress of Salinity and Alkalinity. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 62, 137–153.

- Hafez, E.; Osman, H.; El-Razek, U.; Elbagory, M.; Omara, A.; Eid, M.; Gowayed, S. Foliar-Applied Potassium Silicate Coupled with Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Improves Growth, Physiology, Nutrient Uptake and Productivity of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) Irrigated with Saline Water in Salt-Affected Soil. Plants 2021, 10, 894.

- Omara, A.E.-D.; Hafez, E.M.; Osman, H.S.; Rashwan, E.; El-Said, M.A.A.; Alharbi, K.; El-Moneim, D.A.; Gowayed, S.M. Collaborative Impact of Compost and Beneficial Rhizobacteria on Soil Properties, Physiological Attributes, and Productivity of Wheat Subjected to Deficit Irrigation in Salt Affected Soil. Plants 2022, 11, 877.

- Khalifa, T.; Elbagory, M.; Omara, A.E.-D. Salt Stress Amelioration in Maize Plants through Phosphogypsum Application and Bacterial Inoculation. Plants 2021, 10, 2024.

- Selem, E.; Hassan, A.A.S.A.; Awad, M.F.; Mansour, E.; Desoky, E.-S.M. Impact of Exogenously Sprayed Antioxidants on Physio-Biochemical, Agronomic, and Quality Parameters of Potato in Salt-Affected Soil. Plants 2022, 11, 210.

- Khalifa, T.H. Effectiveness of gypsum application and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation on ameliorating saline-sodic soil characteristics and their productivity. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 165–180.

- El-Nahrawy, S.M. Potassium Silicate and Plant Growth-promoting Rhizobacteria Synergistically Improve Growth Dynamics and Productivity of Wheat in Salt-affected Soils. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 9–25.

- Abdelrasheed, K.G.; Mazrou, Y.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Osman, H.S.; Nehela, Y.; Hafez, E.M.; Rady, A.M.S.; El-Moneim, D.A.; Alowaiesh, B.F.; Gowayed, S.M. Soil Amendment Using Biochar and Application of K-Humate Enhance the Growth, Productivity, and Nutritional Value of Onion (Allium cepa L.) under Deficit Irrigation Conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 2598.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

972

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Sep 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No