| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adalberto Santos-Júnior | + 1653 word(s) | 1653 | 2020-10-14 10:14:07 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 1653 | 2020-10-22 09:53:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

The objective of this research is to propose a theoretical model based on studies on residents’ quality of life in smart tourism destinations. Smart tourism destinations are territories based on information and communication technologies (ICT), which improve travelers’ tourist experiences as well as affect the quality of life of residents. To know the context of the relationships between tourism and quality of life, main studies and theories regarding these two phenomena are analyzed. Likewise, the relationship between smart places and quality of life is also studied.

1. Introduction

The close relationship between perceived tourism impacts and the quality of life of residents is increasingly relevant in tourism research [1][2], as well as the relationship between the quality of life and support for tourism development by the population [3][4]. In this sense, numerous studies show that the quality of life of residents of tourist destinations is affected either positively or negatively by the impacts of tourism (economic, sociocultural, and environmental dimensions) [5][6].

Quality of life (QOL) refers to the general well-being of people’s lives and is fundamentally structured through the concepts of objective and subjective well-being [7]. Objective well-being is measured by means of quantitative indicators of quality of life [8][9], while subjective well-being is measured by means of subjective indicators [1][10].

Our main objective is to propose a theoretical model on the quality of life of residents in smart tourism destinations, based on the subjective well-being approach. This model arises from a systematized review of literature, in order to structure the main conceptual contributions of quality of life in categories in the context of tourism and smart places (cities and destinations). Moreover, this study aims to (i) explain the subjective factors of quality of life, (ii) point out the impacts of tourism and its relationship with quality of life, and (iii) reflect on the quality of life in smart tourism destinations.

2. The Quality of Life of Residents in Destinations

Among the various concepts on quality of life, we highlight that of Cummins [11] (p. 700), which defines quality of life as a construct that “is multidimensional and influenced by personal and environmental factors and their interactions, has the same components for all people, has both objective and subjective components, and is enhanced by self-determination, resources, purpose in life, and a sense of belonging”. Following that line of thought, Felce and Perry [12] (p. 54) define quality of life as “a combination of both life conditions and satisfaction” but taking into account “personal values”.

Objective well-being represents the real circumstances of life. This well-being is measured by quantitative and extrinsic indicators (e.g., economic, social, environmental, and health indicators) [9][10][13], such as gross domestic product (GDP), share of the tourism industry in GDP, unemployment rate, poverty rate, level of education, life expectancy, family income, number of hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants, square meters of green areas (parks) or recreational facilities per thousand inhabitants, public security, number of hotel beds, etc.

On the other hand, subjective well-being refers to the personal feelings and perceptions of life, which are constituted as qualitative and intrinsic indicators. These indicators are related to positive affection, negative affection, and life satisfaction [14]. Positive and negative affection refer to the affective component (emotions, feelings), while life satisfaction is linked to the cognitive aspect (perception, judgment) that a person has regarding life [15][14].

It is noted that much of the research on quality of life in destinations, focuses on the assessment of the subjective well-being of residents [2][8][10][13] or tourists [16][17]. In that sense, from the Bottom-up Spillover Theory [2][4][18][19][20][21][22], the quality of life or overall life satisfaction of the local community is determined by the level of their satisfaction with the specific factors of life (e.g., family, work, community life, safety, health, public services, social networks, cultural and leisure life, etc.) which, in turn are affected by the effects of tourism development [1][3].

In addition, it is also perceived that some authors group specific life factors into two dimensions: material well-being and non-material well-being [1][2][3]. Material well-being refers to the sense of well-being with the economic dimension (e.g., well-being of employment and income, and well-being of costs of living), while non-material well-being refers to the sense of well-being with sociocultural and environmental dimensions (e.g., community well-being, emotional well-being, and health and safety well-being, well-being of community services, well-being with lifestyle, etc.).

The combination of objective and subjective indicators of the quality of life of residents [13][23] can help planners and managers of tourist destinations in the development and implementation of effective and sustainable policies [24][25]. As the quality of life of the local community in tourist destinations improves, the greater the support of residents towards the development of tourism [4][13][26][27][28].

3. Impacts of Tourism on the Quality of Life of Residents

Tourism is a socio-economic activity that, according to Uysal, Sirgy, Woo, and Kim [13], depends on the infrastructure and resources of the community to be able to develop, which generates impacts that affect the quality of life of residents [7][29][30][31][32][33][34], and the well-being of tourists and other agents involved in destinations [2][8][13][24].

It should be noted that much of the research that analyzes the impacts of tourism on the quality of life of residents relate to the following dimensions [7][23][19][26][31]:

-

(i) Economic (e.g., strengthening the local economy, employment opportunities, rising living standards, investment contribution, creation of new businesses, increased tax revenues, increased cost of living, increased price of goods and services, real estate speculation, etc.).

-

(ii)Sociocultural (e.g., social interactions, cultural exchange, preservation of cultural goods, increased leisure and entertainment activities, community well-being, loss of cultural identity, violence and crime, gentrification, tourism, etc.).

-

(iii)Environmental (e.g., preservation of natural resources, increased environmental awareness, better management of natural resources, increased pollution, environmental degradation, waste management/disposal, etc.).

The perception of residents regarding the impacts of tourism on their quality of life can be either positive or negative, leading to either favorable or unfavorable attitudes towards tourism and their support for tourism-based development [7][35][32][33][34]. In relation to the latter aspect, studies based on the Social Exchange Theory highlight that residents assess the costs and benefits of tourism development and its quality of life [18][28][32][36][37].

Thus, it is generally assumed that the economic impacts of tourism are usually perceived as positive by residents, while social and environmental impacts are perceived as more negative [13]. The support of residents to tourism would be more connected with the perception of the positive effects of tourism, especially the economic ones [27], corroborating the principles of the Social Exchange Theory.

In addition to the economic, sociocultural, and environmental impacts of tourism, it can be emphasized that the political context in which destinations are unfolded has a remarkable role [2][38][39][40], which can also have an impact on the quality of life of the community. The main political factors that promote tourism development and the quality of life of residents are participatory democracy, control of corruption, the rule of law [41][42], the stable political environment [10][41], the formulation and implementation of tourism development policies [43], the social capital [44][45], governance [39][42][46], and trust between the agents of destination [39].

4. Smart Places: Smart Cities and Smart Tourism Destinations

The concept of smart tourism destinations arises in literature from 2010 and is closely related to the concept of smart cities [47][48][49]. Despite there being no consensus in the definition, the smart city is basically understood as a territory that is based on ICT [50][51][52][53][54][55][56] that “must be able to optimize the use and exploitation of tangible and intangible assets” [57] (p. 26) through the participation of multiple stakeholders [58], to promote sustainable development [59][60][61], and be able to increase the quality of life of citizens [62][63].

The tangible assets of the smart city relate to natural resources, services, and urban infrastructure [61][64][65][66][67][68][69], while intangible assets include human capital, intellectual capital (private sector), and organizational capital (public sector) [57].

On the other hand, the tourist destination is configured as smart, when it makes intensive use of the ICTs provided by the smart city, transforming into an innovative tourist territory, which guarantees sustainable development [70][71][72], improves the quality of the tourist experience [73][74][75], and increases the quality of life of residents [76][77].

The dimensions and factors of smart tourism destination include governance, sustainability, technology, innovation, accessibility [77], connectivity and smart sensor networks, information system, smart applications/solutions [49][78][79], social and human capital, entrepreneurship, leadership [73], and cultural heritage and creativity [80].

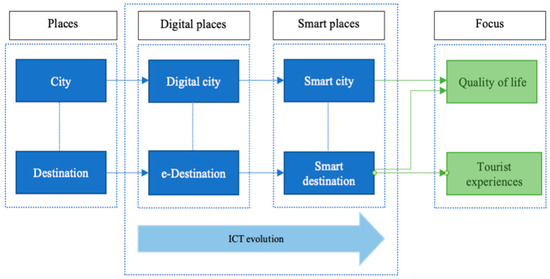

Therefore, it can be considered that both the smart city and the smart tourism destination are urban areas that would be constituted in “smart places” [49][81] through the intensive use of ICTs, which would have as their main purpose the increase in the quality of life of people [62][67], whether residents or tourists (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Purpose of the smart places.

5. Theoretical Model of Residents’ Quality of Life in Smart Tourism Destinations

Based on the analysis of the documents selected in the systematized review, it was possible to determine some preliminary results. It was observed that the quality of life of residents can be measured through subjective well-being (subjective indicators) and objective well-being (objective indicators) [13][25][82][83]. However, it was noted that much of the studies on quality of life in tourist destinations [1][2][3][10], as well as in smart cities [56][61][67][84][85], focus on measuring the subjective well-being of the community. A few tourism studies, such as those of Meng, Li, and Uysal [9], and Urtasun and Gutiérrez [10], assess the quality of life through objective well-being.

Based on preliminary results and taking subjective well-being as an analysis perspective [1][3][24], we propose a theoretical model of the quality of life of residents in smart tourism destinations (QOL-STD). The model consists of five main elements: perceived tourism impacts, ICT, satisfaction with specific life factors, overall life satisfaction, and support for further smart tourism destination development.

It is established that residents’ overall life satisfaction in the development of the smart tourism destination results from the relationship between perceived tourism impacts [1][7] and satisfaction whit specific life factors. On the other hand, we highlight the important role that ICTs play in this model, as they function as cross-cutting factors that influence the perceived tourism impacts and support for further smart tourism destination development [79].

References

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540.

- Woo, E.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Tourism Impact and Stakeholders’ Quality of Life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 260–286.

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97.

- Yu, C.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C. Resident support for tourism development in rural midwestern (USA) communities: Perceived tourism impacts and community quality of life perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 802.

- Almeida-García, F.; Peláez-Fernández, M.Á.; Balbuena-Vazquez, A.; Cortes-Macias, R. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 259–274.

- Ko, D.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530.

- Uysal, M.; Perdue, R.; Sirgy, M.J. Prologue: Tourism and Quality-of-Life (QOL) Research: The Missing Links. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research: Enhancing the Lives of Tourists and Residents of Host Communities; Uysal, M., Perdue, R., Sirgy, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–5.

- Meng, F.; Li, X.; Uysal, M. Tourism Development and Regional Quality of Life: The Case of China. J. China Tour. Res. 2010, 6, 164–182.

- Urtasun, A.; Gutiérrez, I. Tourism agglomeration and its impact on social welfare: An empirical approach to the Spanish case. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 901–912.

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the Nature of Tourism and Quality of Life Perceptions among Residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 248–260.

- Cummins, R.A. Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 699–706.

- Felce, D.; Perry, J. Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Res. Dev. Disabil. 1995, 16, 51–74.

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261.

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–563.

- Theofilou, P. Quality of Life: Definition and Measurement. Eur. J. Psychol. 2013, 9, 150–162.

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476.

- Carneiro, M.J.; Eusébio, C. Factors influencing the impact of tourism on happiness. Anatolia 2019, 30, 475–496.

- Eslami, S.; Khalifah, Z.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D. Impact of non-economic factors on residents’ support for sustainable tourism development in Langkawi Island, Malaysia. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 181–197.

- Eslami, S.; Khalifah, Z.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Han, H. Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 1061–1079.

- Suess, C.; Baloglu, S.; Busser, J.A. Perceived impacts of medical tourism development on community wellbeing. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 232–245.

- Tokarchuk, O.; Gabriele, R.; Maurer, O. Development of city tourism and well-being of urban residents: A case of German Magic Cities. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 343–359.

- Yu, C.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C. Assessing Community Quality of Life in the Context of Tourism Development. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 147–162.

- Jeon, M.M.; Kang, M.; Desmarais, E. Residents’ Perceived Quality of Life in a Cultural-Heritage Tourism Destination. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 105–123.

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Quality-of-life indicators as performance measures. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 291–300.

- Woo, E.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. What Is the Nature of the Relationship Between Tourism Development and the Quality of Life of Host Communities? In Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management; Campón-Cerro, A., Hernández-Mogollón, J., Folgado-Fernández, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 43–62.

- Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Rural destination development based on olive oil tourism: The impact of residents’ community attachment and quality of life on their support for tourism development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1624.

- Porras-Bueno, N.; Plaza-Mejía, M.Á.; Vargas-Sánchez, A. Quality of Life and Perception of the Effects of Tourism: A Contingent Approach. In Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management; Campón-Cerro, A., Hernández-Mogollón, J., Folgado-Fernández, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 109–132.

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of personal benefits from, and support of, tourism development: The role of relational quality and quality-of-life. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 433–454.

- Matarrita-Cascante, D. Changing communities, community satisfaction, and quality of life: A view of multiple perceived indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 98, 105–127.

- Chancellor, C.; Yu, C.S.; Cole, S.T. Exploring quality of life perceptions in rural midwestern (USA) communities: An application of the core-periphery concept in a tourism development context. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 496–507.

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Vogt, C.A.; Knopf, R.C. A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 483–502.

- Nunkoo, R.; So, K.K.F. Residents’ Support for Tourism: Testing Alternative Structural Models. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 847–861.

- Olya, H.G.T.; Gavilyan, Y. Configurational Models to Predict Residents’ Support for Tourism Development. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 893–912.

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J. Effects of Destination Social Responsibility and Tourism Impacts on Residents’ Support for Tourism and Perceived Quality of Life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1039–1057.

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ satisfaction with community attributes and support for tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2011, 35, 171–190.

- Lin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Filieri, R. Resident-tourist value co-creation: The role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 436–442.

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49.

- Butler, R.; Suntikul, W. Political impacts of tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Impacts: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives; Gursoy, D., Nunkoo, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 353–364.

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Rethinking The Role of Power and Trust in Tourism Planning. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 512–522.

- Schenkel, E.; Almeida García, F. La política turística y la intervención del Estado: El caso de Argentina. Perf. Latinoam. 2015, 23, 197–221.

- Wu, H.; Kim, S.; Wong, A.K.F. Residents’ perceptions of desired and perceived tourism impact in Hainan Island. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 583–601.

- Sirgy, M.J. Effects of socioeconomic, political, cultural, and other macro factors on QOL. In The Psychology of Quality of Life; Sirgy, M.J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 63–79.

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination Competitiveness and Its Implications for Host-Community QOL. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research: Enhancing the Lives of Tourists and Residents of Host Communities; Uysal, M., Perdue, R., Sirgy, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 491–513.

- Moscardo, G.; Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; McGehee, N.G.; Schurmann, A. Linking tourism to social capital in destination communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 286–295.

- Moscardo, G.; Murphy, L. There is no such thing as sustainable tourism: Re-conceptualizing tourism as a tool for sustainability. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2538–2561.

- Park, D.; Nunkoo, R.; Yoon, Y. Rural residents’ attitudes to tourism and the moderating effects of social capital. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 112–133.

- Koo, C.; Shin, S.; Gretzel, U.; Hunter, W.C.; Chung, N. Conceptualization of smart tourism destination competitiveness. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 26, 561–576.

- Khan, M.S.; Woo, M.; Nam, K.; Chathoth, P.K. Smart City and Smart Tourism: A Case of Dubai. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2279.

- Invat.tur (Instituto Valenciano de Tecnologías Turísticas). Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes: Manual Iperativo Para la Configuración de Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes. Universidad de Alicante, Instituto Universitario de Investigaciones Turísticas (IUIT). 2015. Available online: http://www.thinktur.org/media/Manual-de-destinos-tur%C3%ADsticos-inteligentes.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2019).

- Abdullah Almaqashi, S.; Lomte, S.S.; Almansob, S.; Al-Rumaim, A.; Jalil, A.A.A. The impact of icts in the development of smart city: Opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 1285–1289.

- Al-Thani, S.K.; Skelhorn, C.P.; Amato, A.; Koc, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Smart Technology Impact on Neighborhood Form for a Sustainable Doha. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4764.

- De Filippi, F.; Coscia, C.; Guido, R. From smart-cities to smart-communities: How can we evaluate the impacts of innovation and inclusive processes in urban context? Int. J. E Plan. Res. 2019, 8, 24–44.

- Lim, Y.; Edelenbos, J.; Gianoli, A. Identifying the results of smart city development: Findings from systematic literature review. Cities 2019, 95.

- Picatoste, J.; Pérez-Ortiz, L.; Ruesga-Benito, S.M.; Novo-Corti, I. Smart cities for wellbeing: Youth employment and their skills on computers. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2018, 9, 227–241.

- Trencher, G.; Karvonen, A. Stretching “smart”: Advancing health and well-being through the smart city agenda. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 610–627.

- Yeh, H. The effects of successful ICT-based smart city services: From citizens’ perspectives. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 556–565.

- Neirotti, P.; De Marco, A.; Cagliano, A.C.; Mangano, G.; Scorrano, F. Current trends in smart city initiatives: Some stylised facts. Cities 2014, 38, 25–36.

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 65–82.

- Capdevila, I.; Zarlenga, M.I. Smart city or smart citizens? The Barcelona case. J. Strategy Manag. 2015, 8, 266–282.

- Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Raman, K.R. Smart cities: Advances in research—An information systems perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 88–100.

- Macke, J.; Rubim Sarate, J.A.; de Atayde Moschen, S. Smart sustainable cities evaluation and sense of community. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 239.

- Pencarelli, T. The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2019.

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding Smart Cities: An Integrative Framework. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 2289–2297.

- Appio, F.P.; Lima, M.; Paroutis, S. Understanding Smart Cities: Innovation ecosystems, technological advancements, and societal challenges. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 1–14.

- Belanche-Gracia, D.; Casaló-Ariño, L.V.; Pérez-Rueda, A. Determinants of multi-service smartcard success for smart cities development: A study based on citizens’ privacy and security perceptions. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 154–163.

- Li, R.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Zheng, B.; Liu, H. Factors affecting smart community service adoption intention: Affective community commitment and motivation theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019.

- Lin, C.; Zhao, G.; Yu, C.; Wu, Y.J. Smart city development and residents’ well-being. Sustainability 2019, 11, 676.

- Schaffers, H.; Ratti, C.; Komninos, N. Special issue on smart applications for smart cities—New approaches to innovation: Guest editors’ introduction. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 7.

- Wirtz, B.W.; Müller, W.M.; Schmidt, F. Public Smart Service Provision in Smart Cities: A Case-Study-Based Approach. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019.

- Shafiee, S.; Ghatari, A.R.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Jahanyan, S. Developing a model for sustainable smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 287–300.

- Perles Ribes, J.F.; Ivars-Baidal, J. Smart sustainability: A new perspective in the sustainable tourism debate. J. Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 151–170.

- Romão, J.; Neuts, B. Territorial capital, smart tourism specialization and sustainable regional development: Experiences from Europe. Habitat Int. 2017, 68, 64–74.

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Conceptualising smart tourism destination dimensions. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 391–403.

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through personalisation of services. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 377–389.

- Huang, C.D.; Goo, J.; Nam, K.; Yoo, C.W. Smart tourism technologies in travel planning: The role of exploration and exploitation. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 757–770.

- López de Ávila, A.; García, S. Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes. Econ. Ind. 2015, 395, 61–69.

- SEGITTUR. Libro Blanco de Los Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes. 2015. Available online: https://www.thinktur.org/media/Libro-Blanco-Destinos-Tursticos-Inteligentes-construyendo-el-futuro.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Neuhofer, B. Smart tourism experiences: Conceptualisation, key dimensions and research agenda. J. Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 129–150.

- Ivars-Baidal, J.; Celdrán Bernabénu, M.A.; Femenia-Serra, F. Guía de Implantación de Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes de la Comunitat Valenciana. 2017. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/74386/4/2017_Ivars-Baidal_etal_Guia-de-implantacion-DTI-CV.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- European Commission. European Capital of Smart Tourism. 2018. Available online: https://smarttourismcapital.eu (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 108–124.

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Kalasek, R.; Pichler-Milanović, N.; Meijers, E. Smart Cities: Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities. Centre of Regional Science, Vienna University of Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2007. Available online: http://www.smart-cities.eu/download/smart_cities_final_report.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2010).

- OECD. How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020.

- Benita, F.; Bansal, G.; Tunçer, B. Public spaces and happiness: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Health Place 2019, 56, 9–18.

- Macke, J.; Casagrande, R.M.; Sarate, J.A.R.; Silva, K.A. Smart city and quality of life: Citizens’ perception in a Brazilian case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 717–726.