| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adina Frum | -- | 3853 | 2022-09-16 14:25:30 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | -4 word(s) | 3849 | 2022-09-19 07:49:13 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3849 | 2022-09-19 07:49:59 | | | | |

| 4 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3849 | 2022-09-19 07:52:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

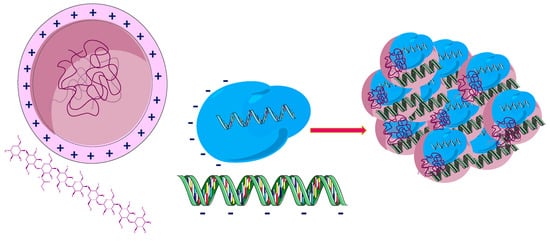

Cancer represents a major public health issue, a substantial economic issue, and a burden for society. Limited by numerous disadvantages, conventional chemotherapy is being replaced by new strategies targeting tumor cells. In this context, therapies based on biopolymer prodrug systems represent a promising alternative for improving the pharmacokinetic and pharmacologic properties of drugs and reducing their toxicity. The polymer-directed enzyme prodrug therapy is based on tumor cell targeting and release of the drug using polymer–drug and polymer–enzyme conjugates. In addition, current trends are oriented towards natural sources. They are biocompatible, biodegradable, and represent a valuable and renewable source. Drug–polymer conjugates based on natural polymers such as chitosan (CTS), hyaluronic acid (HA), dextran (DEX), pullulan (PL), silk fibroin (SF), centyrins (CTR), heparin (HEP), and polysaccharides from Auricularia auricula (AAP) are presented.

1. Chitosan

2. Hyaluronic Acid

- -

-

the use of lipid NPs with adequate HA coating as carriers of biocompatible drugs is an effective means of delivering the drug and at the same time significantly reduce side effects;

- -

-

improved distribution;

- -

-

improved release of drugs in cancer cells due to its high potential of targeted chemotherapy for tumors with increased CD44 receptor expression;

- -

3. Dextran

4. Pullulan

PL is a natural polysaccharide, an exopolysaccharide, composed of maltotriose units, biocompatible biopolymer, biodegradable, non-toxic, nonmutagenic, and noncarcinogenic [121]. It is a product of aerobic metabolism of a species of fungus Aureobasidium pullulans [122]. Structurally, this linear natural polymer consists of three units of glucose, linked by an α-1,4 glycosidic bond, the units of maltotriose thus formed being linked by an α-1,6 glycosidic bond. PL is obtained naturally from starch under the action of the polymorphic fungal species Aureobasidium pullulans [123][124].

PL is a natural polysaccharide, an exopolysaccharide, composed of maltotriose units, biocompatible biopolymer, biodegradable, non-toxic, nonmutagenic, and noncarcinogenic [121]. It is a product of aerobic metabolism of a species of fungus Aureobasidium pullulans [122]. Structurally, this linear natural polymer consists of three units of glucose, linked by an α-1,4 glycosidic bond, the units of maltotriose thus formed being linked by an α-1,6 glycosidic bond. PL is obtained naturally from starch under the action of the polymorphic fungal species Aureobasidium pullulans [123][124].

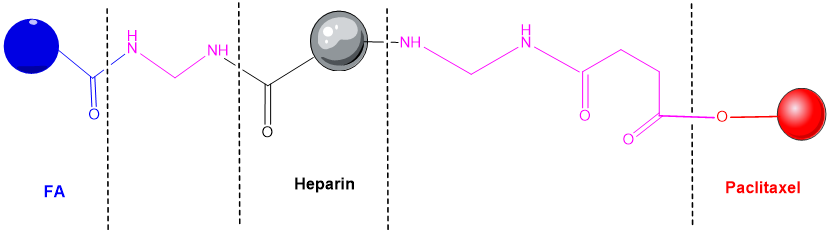

5. Heparin

HEP is a natural polymer and could be considered an alternative for drug delivery in cancer cells. A HEP-FA-PTX conjugate was synthetized. In this conjugate, PTX is attached by covalent bond to FA and HEP (Figure 3). It was used in experiments on tumor xenografts of human cells cultured subcutaneously or on laboratory animals [125]. This polymeric conjugate can self-assemble into spherical mycelium in the aqueous medium by binding PTX to HEP by hydroxyl grouping and a pH sensitive linker. Cytotoxicity tests have shown that this conjugate possesses significant cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 tumor cells, and FA enhances the targeting of the compound [126]. Cell absorption and intracellular distribution was studied by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) [127].

Figure 3. Heparin - folic acid - PTX conjugate [125].

6. Auricularia auricula polysaccharides

A promising drug-delivery system based on a polysaccharide biopolymer was isolated from the medicinal fungus Auricularia auricula. An experimental study concluded that a lectin containing four peptides inhibited the A549 cells proliferation by regulating the expression of some cancer-related genes [128], such as JUN an oncogenic transcription factor [129], TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4) expressed on immune cells and also on tumor cells [130], and MYD88 (myeloid differentiation factor 88) that promotes colorectal cancer cells [131]. NPs containing polysaccharide polymers from Auricularia auricula (AAP) and CTS were very efficient for DOX entrapping and penetrating in tumor cells. Thus, AAP represents a promising option as an antineoplastic drug carrier [132].

7. Protein-drug conjugates and peptide-drug conjugates

7.1. Silk Fibroin

Silk fibroin (SF) produced from the cocoon of Bombyx mori silkworm is widely used and has various biomedical applications, including the controlled release of drugs. Silk fiber derived from other insect species has also been investigated. Silk fibroin consists mainly of fibroin and sericin [133][134][135].

Silk-based delivery systems have excellent properties and can be used to deliver many therapeutic substances for cancer treatment, such as: (i) chemotherapeutics, (ii) nucleic acids, peptides or proteins, (iii) inorganic compounds, (iv) photosensitive molecules, (v) plant derivatives. It has been reported that intracellular degradation of SF NPs is dependent on lysosomal enzymatic function. Therefore, these SF-based nanocarriers perform a critical function, represented by the degradation of the release system, and can be considered a safe in vivo drug delivery systems [134][136].

7.2. Centyrins

Centyrins (CTRs) are non-antibody, small size proteins that are engineered from the human protein Tanascin C (found in extracellular matrix). There are some CTRs’ properties (the lack of disulfide bonds, the small molecular size, increased stability, low immunogenicity, improved tissue penetration, simple drug conjugation, etc) which make these molecules the perfect candidates for targeted delivery applications. CTRs can be conjugated with small interfering ribonucleic acids and an increase in efficiency of gene target modulation was observed [137][138][139].

References

- Ali, M.; Pharm Sci, P.J.; Shakeel, M.; Mehmood, K. Extraction and characterization of high purity chitosan by rapid and simple techniques from mud crabs taken from Abbottabad Enzyme inhibition assays View project Extraction and characterization of high purity chitosan by rapid and simple techniques from mud crabs taken from Abbottabad. Artic. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 32, 171–175.

- Xu, Q.; Wang, C.-H.; Pack, D.W. Polymeric Carriers for Gene Delivery: Chitosan and Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 2350.

- Mohammed, M.A.; Syeda, J.T.M.; Wasan, K.M.; Wasan, E.K. An overview of chitosan nanoparticles and its application in non-parenteral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 53.

- Fatullayeva, S.; Tagiyev, D.; Zeynalov, N.; Mammadova, S.; Aliyeva, E. Recent advances of chitosan-based polymers in biomedical applications and environmental protection. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 259.

- Li, W.; Tan, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Y. Folate chitosan conjugated doxorubicin and pyropheophorbide acid nanoparticles (FCDP–NPs) for enhance photodynamic therapy. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 44426–44437.

- Bergamini, A.; Ferrero, S.; Leone Roberti Maggiore, U.; Scala, C.; Pella, F.; Vellone, V.G.; Petrone, M.; Rabaiotti, E.; Cioffi, R.; Candiani, M.; et al. Folate receptor alpha antagonists in preclinical and early stage clinical development for the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2016, 25, 1405–1412.

- Scaranti, M.; Cojocaru, E.; Banerjee, S.; Banerji, U. Exploiting the folate receptor α in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 349–359.

- Appelbaum, J.S.; Pinto, N.; Orentas, R.J. Promising Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Non-B-Cell Hematological Malignancies, Pediatric Solid Tumors, and Carcinomas. In Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapies Cancer; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 137–163.

- Holm, J.; Hansen, S.I. Characterization of soluble folate receptors (folate binding proteins) in humans. Biological roles and clinical potentials in infection and malignancy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Proteins Proteom. 2020, 1868, 140466.

- Chen, C.; Ke, J.; Zhou, X.E.; Yi, W.; Brunzelle, J.S.; Li, J.; Yong, E.L.; Xu, H.E.; Melcher, K. Structural basis for molecular recognition of folic acid by folate receptors. Nature 2013, 500, 486–489.

- Salazar, M.D.A.; Ratnam, M. The folate receptor: What does it promise in tissue-targeted therapeutics? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007, 26, 141–152.

- Lu, Y.; Wheeler, L.W.; Cross, V.A.; Westrick, E.M.; Lloyd, A.M.; Johnson, T.P.; Parker, N.L.; Leamon, C.P. Abstract 4574: Combinatorial strategies of folate receptor-targeted chemotherapy guided by improved understanding of tumor microenvironment and immunomodulation. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4574.

- Fernández, M.; Javaid, F.; Chudasama, V. Advances in targeting the folate receptor in the treatment/imaging of cancers. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 790–810.

- Lu, Y.; Low, P.S. Folate-mediated delivery of macromolecular anticancer therapeutic agents. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 342–352.

- Birrer, M.J.; Betella, I.; Martin, L.P.; Moore, K.N. Is Targeting the Folate Receptor in Ovarian Cancer Coming of Age? Oncologist 2019, 24, 425–429.

- Cortez, A.J.; Tudrej, P.; Kujawa, K.A.; Lisowska, K.M. Advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 81, 17–38.

- Moore, K.N.; Borghaei, H.; O’Malley, D.M.; Jeong, W.; Seward, S.M.; Bauer, T.M.; Perez, R.P.; Matulonis, U.A.; Running, K.L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Phase 1 dose-escalation study of mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853), a folate receptor α-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with solid tumors. Cancer 2017, 123, 3080–3087.

- Ledermann, J.A.; Canevari, S.; Thigpen, T. Targeting the folate receptor: Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to personalize cancer treatments. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2034–2043.

- Hilgenbrink, A.R.; Low, P.S. Folate Receptor-Mediated Drug Targeting: From Therapeutics to Diagnostics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 2135–2146.

- Li, Y.L.; Van Cuong, N.; Hsieh, M.F. Endocytosis Pathways of the Folate Tethered Star-Shaped PEG-PCL Micelles in Cancer Cell Lines. Polymers 2014, 6, 634–650.

- Xiang, G.; Wu, J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lee, R.J. Synthesis and evaluation of a novel ligand for folate-mediated targeting liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 356, 29–36.

- Zhao, R.; Diop-Bove, N.; Visentin, M.; Goldman, I.D. Mechanisms of Membrane Transport of Folates into Cells and Across Epithelia. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2011, 31, 177–201.

- Yang, S.J.; Lin, F.H.; Tsai, K.C.; Wei, M.F.; Tsai, H.M.; Wong, J.M.; Shieh, M.J. Folic Acid-Conjugated Chitosan Nanoparticles Enhanced Protoporphyrin IX Accumulation in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2010, 21, 679–689.

- Ran, R.; Sun, Q.; Baby, T.; Wibowo, D.; Middelberg, A.P.J.; Zhao, C.X. Multiphase microfluidic synthesis of micro- and nanostructures for pharmaceutical applications. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 169, 78–96.

- Meng, F.; Sun, Y.; Lee, R.J.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Y.; Yan, G.; Wang, Y.; Deng, W.; et al. Folate Receptor-Targeted Albumin Nanoparticles Based on Microfluidic Technology to Deliver Cabazitaxel. Cancers 2019, 11, 1571.

- Kumar, P.; Huo, P.; Liu, B. Formulation Strategies for Folate-Targeted Liposomes and Their Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 381.

- Nogueira, D.R.; Scheeren, L.E.; Macedo, L.B.; Marcolino, A.I.P.; Pilar Vinardell, M.; Mitjans, M.; Rosa Infante, M.; Farooqi, A.A.; Rolim, C.M.B. Inclusion of a pH-responsive amino acid-based amphiphile in methotrexate-loaded chitosan nanoparticles as a delivery strategy in cancer therapy. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 157–168.

- Mangaiyarkarasi, R.; Chinnathambi, S.; Aruna, P.; Ganesan, S. Synthesis and formulation of methotrexate (MTX) conjugated LaF3:Tb3+/chitosan nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 69, 170–178.

- Li, J.; Cai, C.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Sun, T.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Yu, G. Chitosan-Based Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery. Molecules 2018, 23, 2661.

- Hsiao, M.H.; Mu, Q.; Stephen, Z.R.; Fang, C.; Zhang, M. Hexanoyl-chitosan-PEG copolymer coated iron oxide nanoparticles for hydrophobic drug delivery. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 403–407.

- Bhavsar, C.; Momin, M.; Gharat, S.; Omri, A. Functionalized and graft copolymers of chitosan and its pharmaceutical applications. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 1189–1204.

- Wang, Z.; Luo, T.; Cao, A.; Sun, J.; Jia, L.; Sheng, R. Morphology-Variable Aggregates Prepared from Cholesterol-Containing Amphiphilic Glycopolymers: Their Protein Recognition/Adsorption and Drug Delivery Applications. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 136.

- Ferji, K.; Venturini, P.; Cleymand, F.; Chassenieux, C.; Six, J.L. In situ glyco-nanostructure formulation via photo-polymerization induced self-assembly. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 2868–2872.

- Ghaffarian, R.; Pérez-Herrero, E.; Oh, H.; Raghavan, S.R.; Muro, S. Chitosan-Alginate Microcapsules Provide Gastric Protection and Intestinal Release of ICAM-1-Targeting Nanocarriers, Enabling GI Targeting In Vivo. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3382–3393.

- Gan, Q.; Dai, D.; Yuan, Y.; Qian, J.; Sha, S.; Shi, J.; Liu, C. Effect of size on the cellular endocytosis and controlled release of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for intracellular delivery. Biomed. Microdevices 2012, 14, 259–270.

- El-Sawy, H.S.; Al-Abd, A.M.; Ahmed, T.A.; El-Say, K.M.; Torchilin, V.P. Stimuli-Responsive Nano-Architecture Drug-Delivery Systems to Solid Tumor Micromilieu: Past, Present, and Future Perspectives. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10636–10664.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cao, D. Nanoparticle hardness controls the internalization pathway for drug delivery. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 2758–2769.

- Akagi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Kim, H.; Akashi, M. Stabilization of polyion complex nanoparticles composed of poly(amino acid) using hydrophobic interactions. Langmuir 2010, 26, 2406–2413.

- Barclay, T.G.; Day, C.M.; Petrovsky, N.; Garg, S. Review of polysaccharide particle-based functional drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 221, 94–112.

- Ranjbari, J.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Alibakhshi, A.; Tabarzad, M.; Hejazi, M.; Ramezani, M. Anti-Cancer Drug Delivery Using Carbohydrate-Based Polymers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 23, 6019–6032.

- Dheer, D.; Arora, D.; Jaglan, S.; Rawal, R.K.; Shankar, R. Polysaccharides based nanomaterials for targeted anti-cancer drug delivery. J. Drug Target. 2017, 25, 1–16.

- Zamboulis, A.; Michailidou, G.; Koumentakou, I.; Bikiaris, D.N. Polysaccharide 3D Printing for Drug Delivery Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 145.

- Chen, G.; Svirskis, D.; Lu, W.; Ying, M.; Huang, Y.; Wen, J. N-trimethyl chitosan nanoparticles and CSKSSDYQC peptide: N-trimethyl chitosan conjugates enhance the oral bioavailability of gemcitabine to treat breast cancer. J. Control. Release 2018, 277, 142–153.

- Hsu, K.Y.; Hao, W.H.; Wang, J.J.; Hsueh, S.P.; Hsu, P.J.; Chang, L.C.; Hsu, C.S. In vitro and in vivo studies of pharmacokinetics and antitumor efficacy of D07001-F4, an oral gemcitabine formulation. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 379–388.

- Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, L.; Pan, D.; Gong, Q.; Gu, Z.; Luo, K. Enzyme-sensitive biodegradable and multifunctional polymeric conjugate as theranostic nanomedicine. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 11, 207–218.

- Fang, C.; Zhang, M. Nanoparticle-based theragnostics: Integrating diagnostic and therapeutic potentials in nanomedicine. J. Control. Release 2010, 146, 2.

- Chuan, D.; Jin, T.; Fan, R.; Zhou, L.; Guo, G. Chitosan for gene delivery: Methods for improvement and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 268, 25–38.

- Bano, S.; Afzal, M.; Waraich, M.M.; Alamgir, K.; Nazir, S. Paclitaxel loaded magnetic nanocomposites with folate modified chitosan/carboxymethyl surface; a vehicle for imaging and targeted drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 513, 554–563.

- Das, M.; Wang, C.; Bedi, R.; Mohapatra, S.S.; Mohapatra, S. Magnetic micelles for DNA delivery to rat brains after mild traumatic brain injury. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2014, 10, 1539–1548.

- Min, H.S.; You, D.G.; Son, S.; Jeon, S.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S.; Kwon, I.C.; Kim, K. Echogenic Glycol Chitosan Nanoparticles for Ultrasound-Triggered Cancer Theranostics. Theranostics 2015, 5, 1402.

- Roy, K.; Kanwar, R.K.; Kanwar, J.R. LNA aptamer based multi-modal, Fe3O4-saturated lactoferrin (Fe3O4-bLf) nanocarriers for triple positive (EpCAM, CD133, CD44) colon tumor targeting and NIR, MRI and CT imaging. Biomaterials 2015, 71, 84–99.

- Sahoo, A.K.; Banerjee, S.; Ghosh, S.S.; Chattopadhyay, A. Simultaneous RGB emitting Au nanoclusters in chitosan nanoparticles for anticancer gene theranostics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 712–724.

- Nivethaa, E.A.K.; Dhanavel, S.; Narayanan, V.; Vasu, C.A.; Stephen, A. An in vitro cytotoxicity study of 5-fluorouracil encapsulated chitosan/gold nanocomposites towards MCF-7 cells. RSC Adv. 2014, 5, 1024–1032.

- Smith, T.; Affram, K.; Bulumko, E.; Agyare, E.; Author Edward Agyare, C.; Martin Luther, S. Evaluation of in-vitro cytotoxic effect of 5-FU loaded-chitosan nanoparticles against spheroid models. J. Nat. Sci. 2018, 4, e535.

- Liu, B.Y.; He, X.Y.; Xu, C.; Xu, L.; Ai, S.L.; Cheng, S.X.; Zhuo, R.X. A Dual-Targeting Delivery System for Effective Genome Editing and in Situ Detecting Related Protein Expression in Edited Cells. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 2957–2968.

- Zhang, B.C.; Wu, P.Y.; Zou, J.J.; Jiang, J.L.; Zhao, R.R.; Luo, B.Y.; Liao, Y.Q.; Shao, J.W. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 gene-chemo synergistic cancer therapy via a stimuli-responsive chitosan-based nanocomplex elicits anti-tumorigenic pathway effect. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124688.

- Kim, D.; Le, Q.V.; Wu, Y.; Park, J.; Oh, Y.K. Nanovesicle-Mediated Delivery Systems for CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1233.

- Eoh, J.; Gu, L. Biomaterials as vectors for the delivery of CRISPR–Cas9. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 1240–1261.

- Meyer, K.; Palmer, J.W. The Polysaccharide of the Vitreous Humor. J. Biol. Chem. 1934, 107, 629–634.

- Juncan, A.M.; Moisă, D.G.; Santini, A.; Morgovan, C.; Rus, L.L.; Vonica-țincu, A.L.; Loghin, F. Advantages of Hyaluronic Acid and Its Combination with Other Bioactive Ingredients in Cosmeceuticals. Molecules 2021, 26, 4429.

- Lapčík, L.; Lapčík, L.; De Smedt, S.; Demeester, J.; Chabreček, P. Hyaluronan: Preparation, Structure, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 2663–2684.

- Lokeshwar, V.B.; Mirza, S.; Jordan, A. Targeting hyaluronic acid family for cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Adv. Cancer Res. 2014, 123, 35–65.

- Mattheolabakis, G.; Milane, L.; Singh, A.; Amiji, M.M. Hyaluronic acid targeting of CD44 for cancer therapy: From receptor biology to nanomedicine. J. Drug Target. 2015, 23, 605–618.

- Cai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Y.; Cong, F. Hyaluronan-Inorganic Nanohybrid Materials for Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 1677–1696.

- Zhang, M.; Xu, C.; Wen, L.; Han, M.K.; Xiao, B.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Viennois, E.; Merlin, D. A Hyaluronidase-Responsive Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery System for Targeting Colon Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 7208–7218.

- Dosio, F.; Arpicco, S.; Stella, B.; Fattal, E. Hyaluronic acid for anticancer drug and nucleic acid delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 97, 204–236.

- Choi, K.Y.; Saravanakumar, G.; Park, J.H.; Park, K. Hyaluronic acid-based nanocarriers for intracellular targeting: Interfacial interactions with proteins in cancer. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 99, 82–94.

- Lu, B.; Xiao, F.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; Pan, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J. Redox-Sensitive Hyaluronic Acid Polymer Prodrug Nanoparticles for Enhancing Intracellular Drug Self-Delivery and Targeted Cancer Therapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 4106–4115.

- Salari, N.; Mansouri, K.; Valipour, E.; Abam, F.; Jaymand, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Dokaneheifard, S.; Mohammadi, M. Hyaluronic acid-based drug nanocarriers as a novel drug delivery system for cancer chemotherapy: A systematic review. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 29, 439–447.

- Hu, J.; Ni, Z.; Zhu, H.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Shang, Y.; Chen, D.; Liu, H. A novel drug delivery system—Drug crystallization encapsulated liquid crystal emulsion. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 607, 121007.

- Shrestha, S.; Cho, W.; Stump, B.; Imani, J.; Lamattina, A.M.; Louis, P.H.; Pazzanese, J.; Rosas, I.O.; Visner, G.; Perrella, M.A.; et al. FK506 induces lung lymphatic endothelial cell senescence and downregulates LYVE-1 expression, with associated decreased hyaluronan uptake. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 75.

- Misra, S.; Hascall, V.C.; Markwald, R.R.; Ghatak, S. Interactions between Hyaluronan and Its Receptors (CD44, RHAMM) Regulate the Activities of Inflammation and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 201.

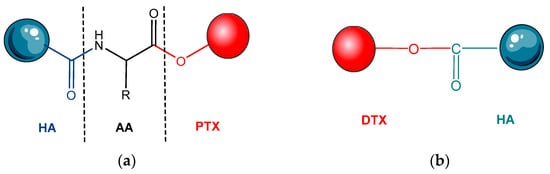

- Shabani Ravari, N.; Goodarzi, N.; Alvandifar, F.; Amini, M.; Souri, E.; Khoshayand, M.R.; Hadavand Mirzaie, Z.; Atyabi, F.; Dinarvand, R. Fabrication and biological evaluation of chitosan coated hyaluronic acid-docetaxel conjugate nanoparticles in CD44+ cancer cells. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 24, 21.

- Xin, D.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, J. The use of amino acid linkers in the conjugation of paclitaxel with hyaluronic acid as drug delivery system: Synthesis, self-assembled property, drug release, and in vitro efficiency. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 380–389.

- Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W. Topological indices of hyaluronic acid-paclitaxel conjugates’ molecular structure in cancer treatment. Open Chem. 2019, 17, 81–87.

- Huang, G.; Huang, H. Application of hyaluronic acid as carriers in drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 766–772.

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Mirzaei, S.; Gholami, M.H.; Hashemi, F.; Zabolian, A.; Raei, M.; Hushmandi, K.; Zarrabi, A.; Voelcker, N.H.; Aref, A.R.; et al. Hyaluronic acid-based nanoplatforms for Doxorubicin: A review of stimuli-responsive carriers, co-delivery and resistance suppression. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118491.

- Parveen, S.; Arjmand, F.; Tabassum, S. Clinical developments of antitumor polymer therapeutics. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 24699–24721.

- Huang, Y.; Song, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Fan, Q.; Wang, L.; Huang, W. Cationic Conjugated Polymer/Hyaluronan-Doxorubicin Complex for Sensitive Fluorescence Detection of Hyaluronidase and Tumor-Targeting Drug Delivery and Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 21529–21537.

- Naguib, Y.W.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Li, X.; Hursting, S.D.; Williams, R.O.; Cui, Z. Solid Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations of DocetaxelPrepared with High Melting Point Triglycerides: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1239.

- Pooja, D.; Kulhari, H.; Adams, D.J.; Sistla, R. Formulation and dosage of therapeutic nanosuspension for active targeting of docetaxel (WO 2014210485A1). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016, 26, 745–749.

- Seifu, M.F.; Nath, L.K.; Dutta, D. Hyaluronic acid-docetaxel conjugate loaded nanoliposomes for targeting tumor cells. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2020, 12, 88–99.

- Banella, S.; Quarta, E.; Colombo, P.; Sonvico, F.; Pagnoni, A.; Bortolotti, F.; Colombo, G. Orphan Designation and Cisplatin/Hyaluronan Complex in an Intracavitary Film for Malignant Mesothelioma. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 362.

- Liu, E.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Cai, Z. Cisplatin loaded hyaluronic acid modified TiO2 nanoparticles for neoadjuvant chemotherapy of ovarian cancer. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 390358.

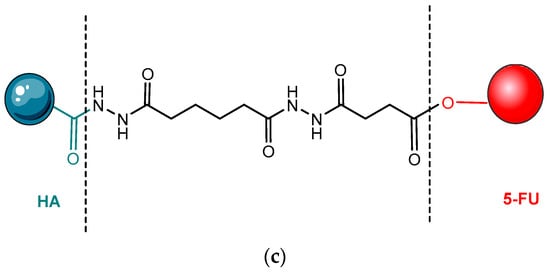

- Dong, Z.; Zheng, W.; Xu, Z.; Yin, Z. Improved stability and tumor targeting of 5-fluorouracil by conjugation with hyaluronan. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 130, 927–932.

- Mero, A.; Campisi, M. Hyaluronic Acid Bioconjugates for the Delivery of Bioactive Molecules. Polymers 2014, 6, 346–369.

- Zhang, R.; Ru, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Mao, S. Layer-by-layer nanoparticles co-loading gemcitabine and platinum (IV) prodrugs for synergistic combination therapy of lung cancer. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2017, 11, 2631.

- Liu, L.; Cao, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Leng, X.; Song, C.; Kong, D.; et al. Hyaluronic Acid-Modified Cationic Lipid-PLGA Hybrid Nanoparticles as a Nanovaccine Induce Robust Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 11969–11979.

- Pramanik, N.; Ranganathan, S.; Rao, S.; Suneet, K.; Jain, S.; Rangarajan, A.; Jhunjhunwala, S. A Composite of Hyaluronic Acid-Modified Graphene Oxide and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery and Magnetothermal Therapy. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 9284–9293.

- Lee, J.E.; Yin, Y.; Lim, S.Y.; Kim, E.S.; Jung, J.; Kim, D.; Park, J.W.; Lee, M.S.; Jeong, J.H. Enhanced Transfection of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Using a Hyaluronic Acid/Calcium Phosphate Hybrid Gene Delivery System. Polymers 2019, 11, 798.

- Fang, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Du, F.; Wang, W.; Shi, R.; Gao, D. Hyaluronic acid-modified mesoporous silica-coated superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 5785–5797.

- Gao, Z.; Li, Z.; Yan, J.; Wang, P. Irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil-co-loaded, hyaluronic acid-modified layer-by-layer nanoparticles for targeted gastric carcinoma therapy. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2017, 11, 2595.

- Baruah, R.; Maina, N.H.; Katina, K.; Juvonen, R.; Goyal, A. Functional food applications of dextran from Weissella cibaria RBA12 from pummelo (Citrus maxima). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 242, 124–131.

- Chen, F.; Huang, G.; Huang, H. Preparation and application of dextran and its derivatives as carriers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 827–834.

- Thomas, T.J.; Tajmir-Riahi, H.A.; Pillai, C.K.S. Biodegradable Polymers for Gene Delivery. Molecules 2019, 24, 3744.

- Sood, A.; Gupta, A.; Agrawal, G. Recent advances in polysaccharides based biomaterials for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100067.

- Lix, K.; Tran, M.V.; Massey, M.; Rees, K.; Sauvé, E.R.; Hudson, Z.M.; Russ Algar, W. Dextran Functionalization of Semiconducting Polymer Dots and Conjugation with Tetrameric Antibody Complexes for Bioanalysis and Imaging. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2020, 3, 432–440.

- Mayder, D.M.; Tonge, C.M.; Nguyen, G.D.; Tran, M.V.; Tom, G.; Darwish, G.H.; Gupta, R.; Lix, K.; Kamal, S.; Algar, W.R.; et al. Polymer Dots with Enhanced Photostability, Quantum Yield, and Two-Photon Cross-Section using Structurally Constrained Deep-Blue Fluorophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16976–16992.

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Q.; Dai, X.; Ling, P.; Gao, F. Engineering fluorescent semiconducting polymer nanoparticles for biological applications and beyond. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 1989–2004.

- Pasut, G. Polymers for Protein Conjugation. Polymers 2014, 6, 160–178.

- Cheung, R.Y.; Ying, Y.; Rauth, A.M.; Marcon, N.; Wu, X.Y. Biodegradable dextran-based microspheres for delivery of anticancer drug mitomycin C. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5375–5385.

- Feng, Q.; Tong, R. Anticancer nanoparticulate polymer-drug conjugate. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2016, 1, 277–296.

- Ferreira Soares, D.C.; Oda, C.M.R.; Monteiro, L.O.F.; de Barros, A.L.B.; Tebaldi, M.L. Responsive polymer conjugates for drug delivery applications: Recent advances in bioconjugation methodologies. J. Drug Target. 2019, 27, 355–366.

- Pang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhai, G. Polymer-drug conjugates: Recent progress on administration routes. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 1075–1086.

- Duncan, R. The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 347–360.

- Jain, R.K.; Stylianopoulos, T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 653–664.

- Xie, J.; Lee, S.; Chen, X. Nanoparticle-based theranostic agents. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 1064–1079.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zheng, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Fallon, J.K.; Fu, Q.; Haynes, M.T.; Lin, G.; et al. Disulfide bond bridge insertion turns hydrophobic anticancer prodrugs into self-assembled nanomedicines. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5577–5583.

- Kanwal, S.; Naveed, M.; Arshad, A.; Arshad, A.; Firdous, F.; Faisal, A.; Yameen, B. Reduction-Sensitive Dextran-Paclitaxel Polymer-Drug Conjugate: Synthesis, Self-Assembly into Nanoparticles, and in Vitro Anticancer Efficacy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2021, 32, 2516–2529.

- Abdulrahman, L.; Oladapo Bakare, M.A. The Chemical Approach of Methotrexate Targeting. Front. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 1, 50–73.

- Park, K.B.; Jeong, Y.I.; Choi, K.C.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, H.K. Adriamycin-incorporated nanoparticles of deoxycholic acid-conjugated dextran: Antitumor activity against CT26 colon carcinoma. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011, 11, 4240–4249.

- Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, R.; Li, S.; Hu, H.; Xiao, C.; Wu, H.; Zhu, L.; Ming, J.; Chu, Z.; et al. Self-assembly of folic acid dextran conjugates for cancer chemotherapy. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 17265–17274.

- Ghadiri, M.; Vasheghani-Farahani, E.; Atyabi, F.; Kobarfard, F.; Mohamadyar-Toupkanlou, F.; Hosseinkhani, H. Transferrin-conjugated magnetic dextran-spermine nanoparticles for targeted drug transport across blood-brain barrier. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2017, 105, 2851–2864.

- Peng, M.; Li, H.; Luo, Z.; Kong, J.; Wan, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, H.; Vermorken, A.; Van De Ven, W.; et al. Dextran-coated superparamagnetic nanoparticles as potential cancer drug carriers in vivo. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11155–11162.

- Zhang, J.; Misra, R.D.K. Magnetic drug-targeting carrier encapsulated with thermosensitive smart polymer: Core–shell nanoparticle carrier and drug release response. Acta Biomater. 2007, 3, 838–850.

- Wang, H.; Zhu, W.; Liu, J.; Dong, Z.; Liu, Z. pH-Responsive Nanoscale Covalent Organic Polymers as a Biodegradable Drug Carrier for Combined Photodynamic Chemotherapy of Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 14475–14482.

- Wu, Y.; Kuang, H.; Xie, Z.; Chen, X.; Jing, X.; Huang, Y. Novel hydroxyl-containing reduction-responsive pseudo-poly(aminoacid) via click polymerization as an efficient drug carrier. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 4488–4498.

- Feng, J.; Wen, W.; Jia, Y.G.; Liu, S.; Guo, J. pH-Responsive Micelles Assembled by Three-Armed Degradable Block Copolymers with a Cholic Acid Core for Drug Controlled-Release. Polymers 2019, 11, 511.

- Xue, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Xu, B.; Chen, Z.; Li, T. pH and Reduction Dual-Responsive Bi-Drugs Conjugated Dextran Assemblies for Combination Chemotherapy and In Vitro Evaluation. Polymers 2021, 13, 1515.

- Wu, H.; Jin, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ruan, H.; Sun, L.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Qin, W.; Wang, C. Synergistic Cisplatin/Doxorubicin Combination Chemotherapy for Multidrug-Resistant Cancer via Polymeric Nanogels Targeting Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 9426–9436.

- Sharma, A.K.; Keservani, R.K.; Kesharwani, R.K. (Eds.) Nanobiomaterials: Applications in Drug Delivery; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781774636442.

- Sugumaran, K.R.; Ponnusami, V. Review on production, downstream processing and characterization of microbial pullulan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 173, 573–591.

- Singh, R. Pullulan, the Magical Polysaccharide; LAP Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2015; ISBN 3659764213.

- Rekha, M.R.; Sharma, C.P. Pullulan as a promising biomaterial for biomedical applications: A perspective-Document-Gale Academic OneFile. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs. 2007, 20, 116–121.

- Meng, Z.; Lv, Q.; Lu, J.; Yao, H.; Lv, X.; Jiang, F.; Lu, A.; Zhang, G. Prodrug Strategies for Paclitaxel. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 796.

- Li, Q.; Gan, L.; Tao, H.; Wang, Q.; Ye, L.; Zhang, A.; Feng, Z. The synthesis and application of heparin-based smart drug carrier. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 140, 260–268.

- Li, Q.; Ye, L.; Zhang, A.; Feng, Z. The preparation and morphology control of heparin-based pH sensitive polyion complexes and their application as drug carriers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 211, 370–379.

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Xue, B.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, X. A New Lectin from Auricularia auricula Inhibited the Proliferation of Lung Cancer Cells and Improved Pulmonary Flora. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5597135.

- Vogt, P.K. Fortuitous convergences: The beginnings of JUN. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 465–469.

- Li, J.; Yang, F.; Wei, F.; Ren, X. The role of toll-like receptor 4 in tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 66656.

- Zhu, G.; Cheng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Yang, S.; Lin, C.; Ye, J. MyD88 mediates colorectal cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion via NF-κB/AP-1 signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 131.

- Xiong, W.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Pan, W.; Yang, X. Design and evaluation of a novel potential carrier for a hydrophilic antitumor drug: Auricularia auricular polysaccharide-chitosan nanoparticles as a delivery system for doxorubicin hydrochloride. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 511, 267–275.

- Pandey, V.; Haider, T.; Jain, P.; Gupta, P.N.; Soni, V. Silk as a leading-edge biological macromolecule for improved drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 101294.

- Florczak, A.; Grzechowiak, I.; Deptuch, T.; Kucharczyk, K.; Kaminska, A.; Dams-Kozlowska, H. Silk Particles as Carriers of Therapeutic Molecules for Cancer Treatment. Materials 2020, 13, 4946.

- Craig, C.L. Evolution of arthropod silks. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1997, 42, 231–267.

- Seib, F.P.; Seib, F.P. Silk nanoparticles—An emerging anticancer nanomedicine. AIMS Bioeng. 2017, 4, 239–258.

- Centyrin Platform|Aro Biotherapeutics. Available online: https://www.arobiotx.com/centyrin-platform (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Klein, D.; Goldberg, S.; Theile, C.S.; Dambra, R.; Haskell, K.; Kuhar, E.; Lin, T.; Parmar, R.; Manoharan, M.; Richter, M.; et al. Centyrin ligands for extrahepatic delivery of siRNA. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2053–2066.

- Goldberg, S.D.; Cardoso, R.M.F.; Lin, T.; Spinka-Doms, T.; Klein, D.; Jacobs, S.A.; Dudkin, V.; Gilliland, G.; O’Neil, K.T. Engineering a targeted delivery platform using Centyrins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2016, 29, 563–572.