Video Upload Options

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) has been increasingly important for the discovery of new inhibitors targeting Rat Sarcoma (RAS) and its upstream or downstream signaling pathways. Based on high-resolution 3D apo or complex structures of RAS and its upstream and downstream proteins, structure-based CADD (SB-CADD) is the optimal strategy for successful inhibitor discovery, especially virtual high-throughput screening (vHTS) in combination with molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. In addition, ligand-based CADD (LB-CADD) is also an essential strategy for inhibitor discovery that includes quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) and pharmacophore modeling. More advanced computer algorithms, such as machine learning, are also promising for the discovery of RAS-related inhibitors.

1. Determination of the Target Protein Structure

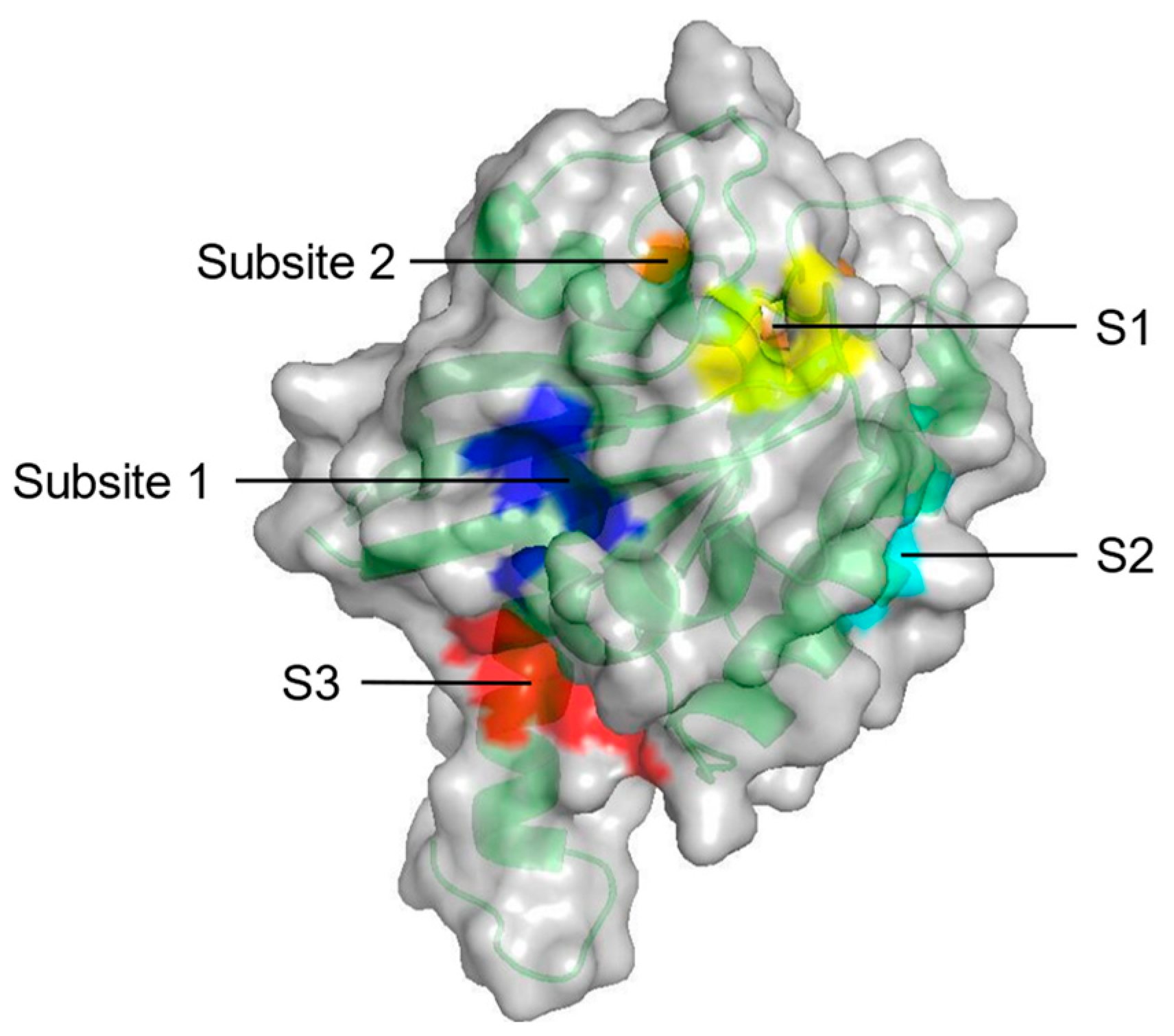

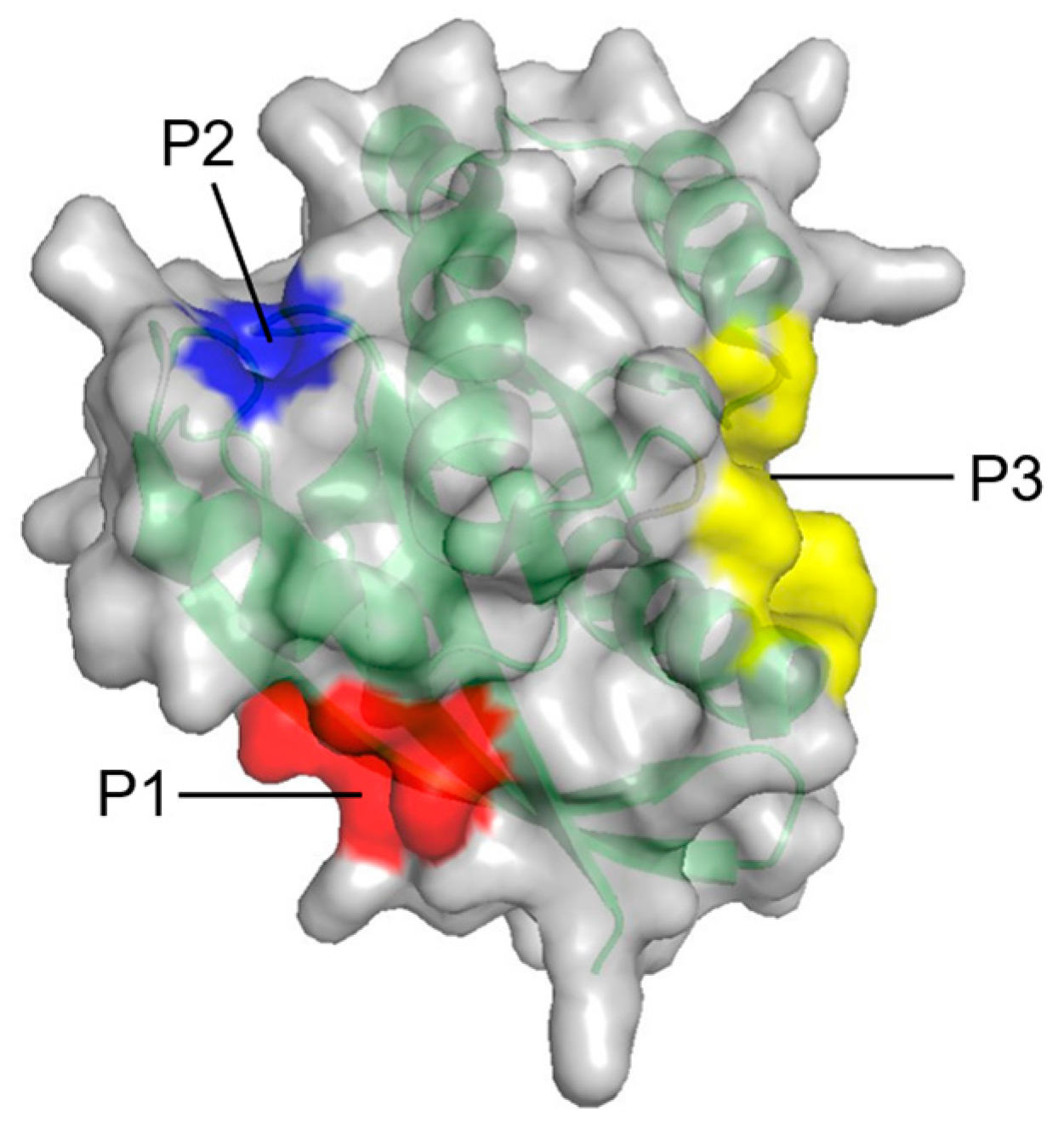

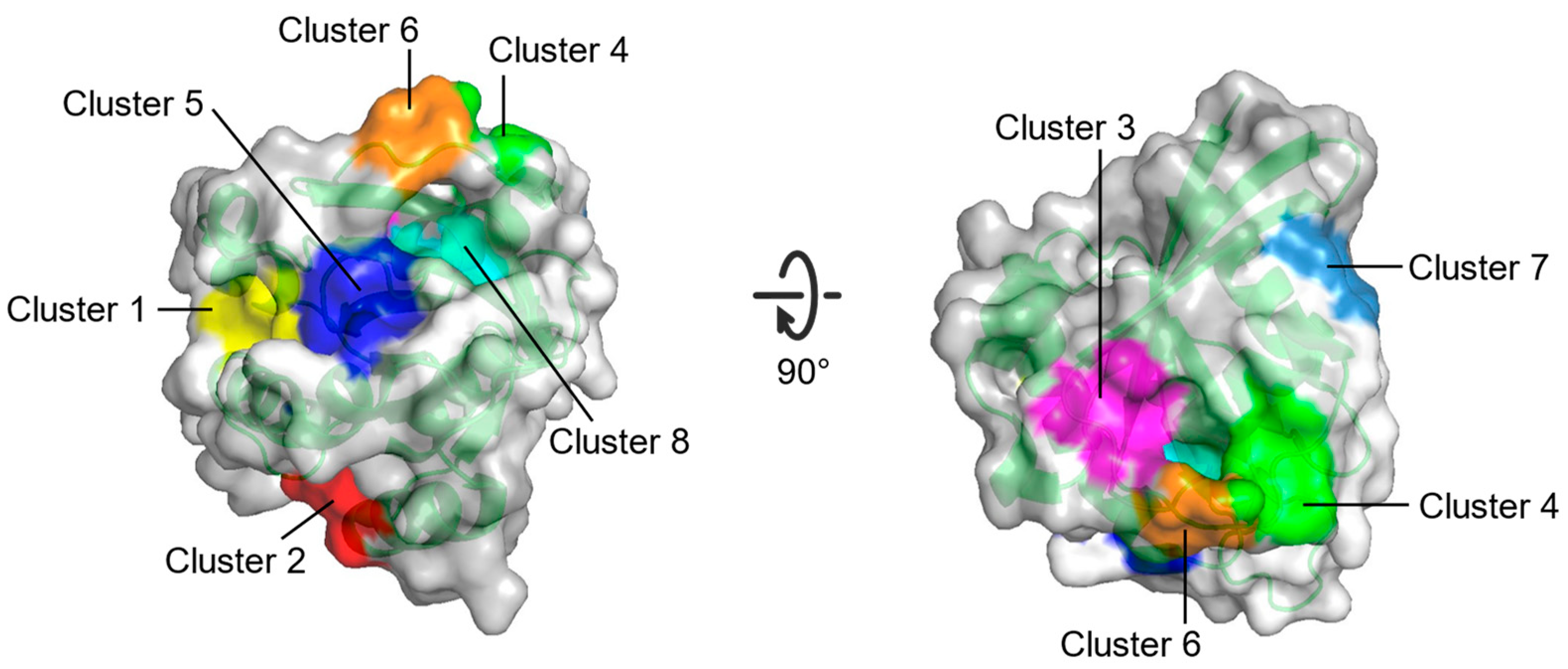

2. Identification of Binding Sites

3. Virtual Screening

4. Molecular Docking Studies

5. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

6. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Study (QSAR)

7. Pharmacophore Modelling

8. Other CADD Applications

References

- Burley, S.K.; Berman, H.M.; Kleywegt, G.J.; Markley, J.L.; Nakamura, H.; Velankar, S. Protein Data Bank (PDB): The Single Global Macromolecular Structure Archive. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1607, 627–641.

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303.

- Eswar, N.; Webb, B.; Marti-Renom, M.A.; Madhusudhan, M.S.; Eramian, D.; Shen, M.Y.; Pieper, U.; Sali, A. Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2007, 50, 2.9.1–2.9.31.

- Donninger, H.; Hesson, L.; Vos, M.; Beebe, K.; Gordon, L.; Sidransky, D.; Liu, J.W.; Schlegel, T.; Payne, S.; Hartmann, A.; et al. The Ras effector RASSF2 controls the PAR-4 tumor suppressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 2608–2620.

- Kanwal, S.; Jamil, F.; Ali, A.; Sehgal, S.A. Comparative Modeling, Molecular Docking, and Revealing of Potential Binding Pockets of RASSF2; a Candidate Cancer Gene. Interdiscip. Sci. 2017, 9, 214–223.

- Collier, T.A.; Piggot, T.J.; Allison, J.R. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2073, 311–327.

- Prakash, P.; Sayyed-Ahmad, A.; Cho, K.J.; Dolino, D.M.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Grant, B.J.; Hancock, J.F.; Gorfe, A.A. Computational and biochemical characterization of two partially overlapping interfaces and multiple weak-affinity K-Ras dimers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40109.

- Bhaskar, B.V.; Rammohan, A.; Babu, T.M.; Zheng, G.Y.; Chen, W.; Rajendra, W.; Zyryanov, G.V.; Gu, W. Molecular insight into isoform specific inhibition of PI3K-alpha and PKC-eta with dietary agents through an ensemble pharmacophore and docking studies. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12150.

- Parca, L.; Mangone, I.; Gherardini, P.F.; Ausiello, G.; Helmer-Citterich, M. Phosfinder: A web server for the identification of phosphate-binding sites on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W278–W282.

- Singh, H.; Srivastava, H.K.; Raghava, G.P. A web server for analysis, comparison and prediction of protein ligand binding sites. Biol. Direct 2016, 11, 14.

- Hernandez, M.; Ghersi, D.; Sanchez, R. SITEHOUND-web: A server for ligand binding site identification in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W413–W416.

- Konc, J.; Skrlj, B.; Erzen, N.; Kunej, T.; Janezic, D. GenProBiS: Web server for mapping of sequence variants to protein binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W253–W259.

- Wang, Y.; Lupala, C.S.; Liu, H.; Lin, X. Identification of Drug Binding Sites and Action Mechanisms with Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 2268–2277.

- Prakash, P.; Hancock, J.F.; Gorfe, A.A. Binding hotspots on K-ras: Consensus ligand binding sites and other reactive regions from probe-based molecular dynamics analysis. Proteins 2015, 83, 898–909.

- Brenke, R.; Kozakov, D.; Chuang, G.Y.; Beglov, D.; Hall, D.; Landon, M.R.; Mattos, C.; Vajda, S. Fragment-based identification of druggable ‘hot spots’ of proteins using Fourier domain correlation techniques. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 621–627.

- Grant, B.J.; Lukman, S.; Hocker, H.J.; Sayyah, J.; Brown, J.H.; McCammon, J.A.; Gorfe, A.A. Novel allosteric sites on Ras for lead generation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25711.

- Mattos, C.; Bellamacina, C.R.; Peisach, E.; Pereira, A.; Vitkup, D.; Petsko, G.A.; Ringe, D. Multiple solvent crystal structures: Probing binding sites, plasticity and hydration. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 357, 1471–1482.

- Buhrman, G.; O’Connor, C.; Zerbe, B.; Kearney, B.M.; Napoleon, R.; Kovrigina, E.A.; Vajda, S.; Kozakov, D.; Kovrigin, E.L.; Mattos, C. Analysis of binding site hot spots on the surface of Ras GTPase. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 413, 773–789.

- Broomhead, N.K.; Soliman, M.E. Can We Rely on Computational Predictions To Correctly Identify Ligand Binding Sites on Novel Protein Drug Targets? Assessment of Binding Site Prediction Methods and a Protocol for Validation of Predicted Binding Sites. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 75, 15–23.

- Long, P.Q.; Quan, P.M. Virtual screening stategies in drug discovery–A brief overview. Vietnam. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 59, 415–440.

- Vázquez, J.; López, M.; Gibert, E.; Herrero, E.; Luque, F.J. Merging ligand-based and structure-based methods in drug discovery: An overview of combined virtual screening approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 4723.

- Qin, T.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.S.; Xia, J.; Wu, S. Computational representations of protein–ligand interfaces for structure-based virtual screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 1175–1192.

- Hunter, J.C.; Manandhar, A.; Carrasco, M.A.; Gurbani, D.; Gondi, S.; Westover, K.D. Biochemical and Structural Analysis of Common Cancer-Associated KRAS Mutations. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 1325–1335.

- Pantsar, T.; Rissanen, S.; Dauch, D.; Laitinen, T.; Vattulainen, I.; Poso, A. Assessment of mutation probabilities of KRAS G12 missense mutants and their long-timescale dynamics by atomistic molecular simulations and Markov state modeling. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006458.

- Hashemi, S.; Sharifi, A.; Zareei, S.; Mohamedi, G.; Biglar, M.; Amanlou, M. Discovery of direct inhibitor of KRAS oncogenic protein by natural products: A combination of pharmacophore search, molecular docking, and molecular dynamic studies. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 15, 226–240.

- Bhagat, R.T.; Butle, S.R.; Khobragade, D.S.; Wankhede, S.B.; Prasad, C.C.; Mahure, D.S.; Armarkar, A.V. Molecular Docking in Drug Discovery. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 33, 46–58.

- Mezei, M. A new method for mapping macromolecular topography. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2003, 21, 463–472.

- Desta, I.T.; Porter, K.A.; Xia, B.; Kozakov, D.; Vajda, S. Performance and Its Limits in Rigid Body Protein-Protein Docking. Structure 2020, 28, 1071–1081.e3.

- Koshland, D.E., Jr.; Neet, K.E. The catalytic and regulatory properties of enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1968, 37, 359–410.

- Pagadala, N.S.; Syed, K.; Tuszynski, J. Software for molecular docking: A review. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 91–102.

- Monticelli, L.; Tieleman, D.P. Force fields for classical molecular dynamics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 924, 197–213.

- Moore, A.R.; Rosenberg, S.C.; McCormick, F.; Malek, S. RAS-targeted therapies: Is the undruggable drugged? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 533–552.

- Ho, C.L.; Wang, J.L.; Lee, C.C.; Cheng, H.Y.; Wen, W.C.; Cheng, H.H.; Chen, M.C. Antroquinonol blocks Ras and Rho signaling via the inhibition of protein isoprenyltransferase activity in cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2014, 68, 1007–1014.

- Luo, C.; Xie, P.; Marmorstein, R. Identification of BRAF inhibitors through in silico screening. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6121–6127.

- Hansson, T.; Oostenbrink, C.; van Gunsteren, W. Molecular dynamics simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002, 12, 190–196.

- Garrido Torres, J.A.; Jennings, P.C.; Hansen, M.H.; Boes, J.R.; Bligaard, T. Low-Scaling Algorithm for Nudged Elastic Band Calculations Using a Surrogate Machine Learning Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 156001.

- Husic, B.E.; Pande, V.S. Markov State Models: From an Art to a Science. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2386–2396.

- Bucher, D.; Pierce, L.C.; McCammon, J.A.; Markwick, P.R. On the Use of Accelerated Molecular Dynamics to Enhance Configurational Sampling in Ab Initio Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 890–897.

- Lu, S.; Ni, D.; Wang, C.; He, X.; Lin, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. Deactivation Pathway of Ras GTPase Underlies Conformational Substates as Targets for Drug Design. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 7188–7196.

- Lu, S.; Jang, H.; Zhang, J.; Nussinov, R. Inhibitors of Ras-SOS Interactions. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 814–821.

- Wittinghofer, A.; Vetter, I.R. Structure-function relationships of the G domain, a canonical switch motif. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 943–971.

- Kano, Y.; Gebregiworgis, T.; Marshall, C.B.; Radulovich, N.; Poon, B.P.K.; St-Germain, J.; Cook, J.D.; Valencia-Sama, I.; Grant, B.M.M.; Herrera, S.G.; et al. Tyrosyl phosphorylation of KRAS stalls GTPase cycle via alteration of switch I and II conformation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 224.

- Wang, Y.; Ji, D.; Lei, C.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Ni, D.; Pu, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Mechanistic insights into the effect of phosphorylation on Ras conformational dynamics and its interactions with cell signaling proteins. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1184–1199.

- Pantsar, T. KRAS(G12C)-AMG 510 interaction dynamics revealed by all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11992.

- Khrenova, M.G.; Kulakova, A.M.; Nemukhin, A.V. Proof of concept for poor inhibitor binding and efficient formation of covalent adducts of KRAS(G12C) and ARS compounds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 3069–3081.

- Muratcioglu, S.; Chavan, T.S.; Freed, B.C.; Jang, H.; Khavrutskii, L.; Freed, R.N.; Dyba, M.A.; Stefanisko, K.; Tarasov, S.G.; Gursoy, A.; et al. GTP-Dependent K-Ras Dimerization. Structure 2015, 23, 1325–1335.

- Ambrogio, C.; Kohler, J.; Zhou, Z.W.; Wang, H.; Paranal, R.; Li, J.; Capelletti, M.; Caffarra, C.; Li, S.; Lv, Q.; et al. KRAS Dimerization Impacts MEK Inhibitor Sensitivity and Oncogenic Activity of Mutant KRAS. Cell 2018, 172, 857–868.e15.

- Sarkar-Banerjee, S.; Sayyed-Ahmad, A.; Prakash, P.; Cho, K.J.; Waxham, M.N.; Hancock, J.F.; Gorfe, A.A. Spatiotemporal Analysis of K-Ras Plasma Membrane Interactions Reveals Multiple High Order Homo-oligomeric Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13466–13475.

- Lu, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, J. Allosteric Methods and Their Applications: Facilitating the Discovery of Allosteric Drugs and the Investigation of Allosteric Mechanisms. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 492–500.

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Cao, Y.; Wu, G.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shi, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. ASD: A comprehensive database of allosteric proteins and modulators. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D663–D669.

- Lu, S.; He, X.; Ni, D.; Zhang, J. Allosteric Modulator Discovery: From Serendipity to Structure-Based Design. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 6405–6421.

- Feng, L.; Lu, S.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, K.; Xue, H.; Jin, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; et al. Identification of an allosteric hotspot for additive activation of PPARγ in antidiabetic effects. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 1559–1570.

- Ni, D.; Wei, J.; He, X.; Rehman, A.U.; Li, X.; Qiu, Y.; Pu, J.; Lu, S.; Zhang, J. Discovery of cryptic allosteric sites using reversed allosteric communication by a combined computational and experimental strategy. Chem. Sci. 2020, 12, 464–476.

- Lu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhao, M.; Ni, D.; He, X.; Zhang, J. Mechanism of allosteric activation of SIRT6 revealed by the action of rationally designed activators. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1355–1361.

- Li, X.; Dai, J.; Ni, D.; He, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S. Insight into the mechanism of allosteric activation of PI3Kα by oncoprotein K-Ras4B. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 643–655.

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Peng, T.; Chai, Z.; Ni, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, T.; Lu, S. Atomic-scale insights into allosteric inhibition and evolutional rescue mechanism of Streptococcus thermophilus Cas9 by the anti-CRISPR protein AcrIIA6. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 6108–6124.

- Nussinov, R.; Tsai, C.J.; Jang, H. Does Ras Activate Raf and PI3K Allosterically? Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1231.

- Lu, S.; He, X.; Yang, Z.; Chai, Z.; Zhou, S.; Wang, J.; Rehman, A.U.; Ni, D.; Pu, J.; Sun, J.; et al. Activation pathway of a G protein-coupled receptor uncovers conformational intermediates as targets for allosteric drug design. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4721.

- Gorfe, A.A. Mechanisms of allostery and membrane attachment in Ras GTPases: Implications for anti-cancer drug discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 1–9.

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ni, D.; Huang, Z.; Wei, J.; Feng, L.; Su, J.C.; Wei, Y.; Ning, S.; Yang, X.; et al. Targeting a cryptic allosteric site of SIRT6 with small-molecule inhibitors that inhibit the migration of pancreatic cancer cells. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 876–889.

- Ni, D.; Song, K.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S. Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Dynamic Network Analysis Reveal the Allosteric Unbinding of Monobody to H-Ras Triggered by R135K Mutation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2249.

- Polanski, J. Receptor dependent multidimensional QSAR for modeling drug—Receptor interactions. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 3243–3257.

- Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E.N.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y.C.; Todeschini, R.; et al. QSAR modeling: Where have you been? Where are you going to? J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4977–5010.

- Jilek, R.J.; Cramer, R.D. Topomers: A validated protocol for their self-consistent generation. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1221–1227.

- Seidel, T.; Schuetz, D.A.; Garon, A.; Langer, T. The Pharmacophore Concept and Its Applications in Computer-Aided Drug Design. Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 2019, 110, 99–141.

- Wermuth, C.G.; Ganellin, C.R.; Lindberg, P.; Mitscher, L.A. Glossary of terms used in medicinal chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1998). Pure Appl. Chem. 1998, 70, 1129–1143.

- Yang, S.Y. Pharmacophore modeling and applications in drug discovery: Challenges and recent advances. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 444–450.

- Wei, D.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; He, C.; Yang, K.; Liu, Y.; Pei, J.; Lai, L. Discovery of multitarget inhibitors by combining molecular docking with common pharmacophore matching. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7882–7888.

- Parate, S.; Kumar, V.; Hong, J.C.; Lee, K.W. Investigation of marine-derived natural products as Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP)-binding ligands. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 581.

- Xie, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, X.; Qiu, K.; Fu, J. A combined pharmacophore modeling, 3D QSAR and virtual screening studies on imidazopyridines as B-Raf inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 12307–12323.

- Dou, J.; Vorobieva, A.A.; Sheffler, W.; Doyle, L.A.; Park, H.; Bick, M.J.; Mao, B.; Foight, G.W.; Lee, M.Y.; Gagnon, L.A.; et al. De novo design of a fluorescence-activating beta-barrel. Nature 2018, 561, 485–491.

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Xiong, P.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H. De novo sequence redesign of a functional Ras-binding domain globally inverted the surface charge distribution and led to extreme thermostability. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 2031–2042.

- Song, L.F.; Merz, K.M., Jr. Evolution of Alchemical Free Energy Methods in Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 5308–5318.

- Wang, E.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.Z.H.; Hou, T. End-Point Binding Free Energy Calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: Strategies and Applications in Drug Design. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9478–9508.

- Mortier, J.; Friberg, A.; Badock, V.; Moosmayer, D.; Schroeder, J.; Steigemann, P.; Siegel, F.; Gradl, S.; Bauser, M.; Hillig, R.C.; et al. Computationally Empowered Workflow Identifies Novel Covalent Allosteric Binders for KRAS(G12C). ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 827–832.

- Melville, J.L.; Burke, E.K.; Hirst, J.D. Machine learning in virtual screening. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2009, 12, 332–343.

- Eckert, H.; Bajorath, J. Molecular similarity analysis in virtual screening: Foundations, limitations and novel approaches. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 225–233.