| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deirdre Prischmann-Voldseth | -- | 1109 | 2022-09-08 21:56:08 | | | |

| 2 | Deirdre Prischmann-Voldseth | -3 word(s) | 1106 | 2022-09-08 22:02:06 | | | | |

| 3 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1106 | 2022-09-09 03:32:13 | | |

Video Upload Options

Fireflies are well-known bioluminescent beetles (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) of great cultural significance, especially in Japan. This study examined artistic representations of fireflies and depictions of how people interacted with these insects from a historical perspective, with a focus on Japanese woodprint prints from the Edo, Meiji, and Taishō periods. Visual information from the artwork was summarized, highlighting themes and connections to firefly biology and cultural entomology. The artwork highlights the complex interactions between fireflies and humans. Insect-related art can contribute to education and conservation efforts, particularly for dynamic insects such as fireflies that are facing global population declines.

1. Introduction

2. Focus on Fireflies

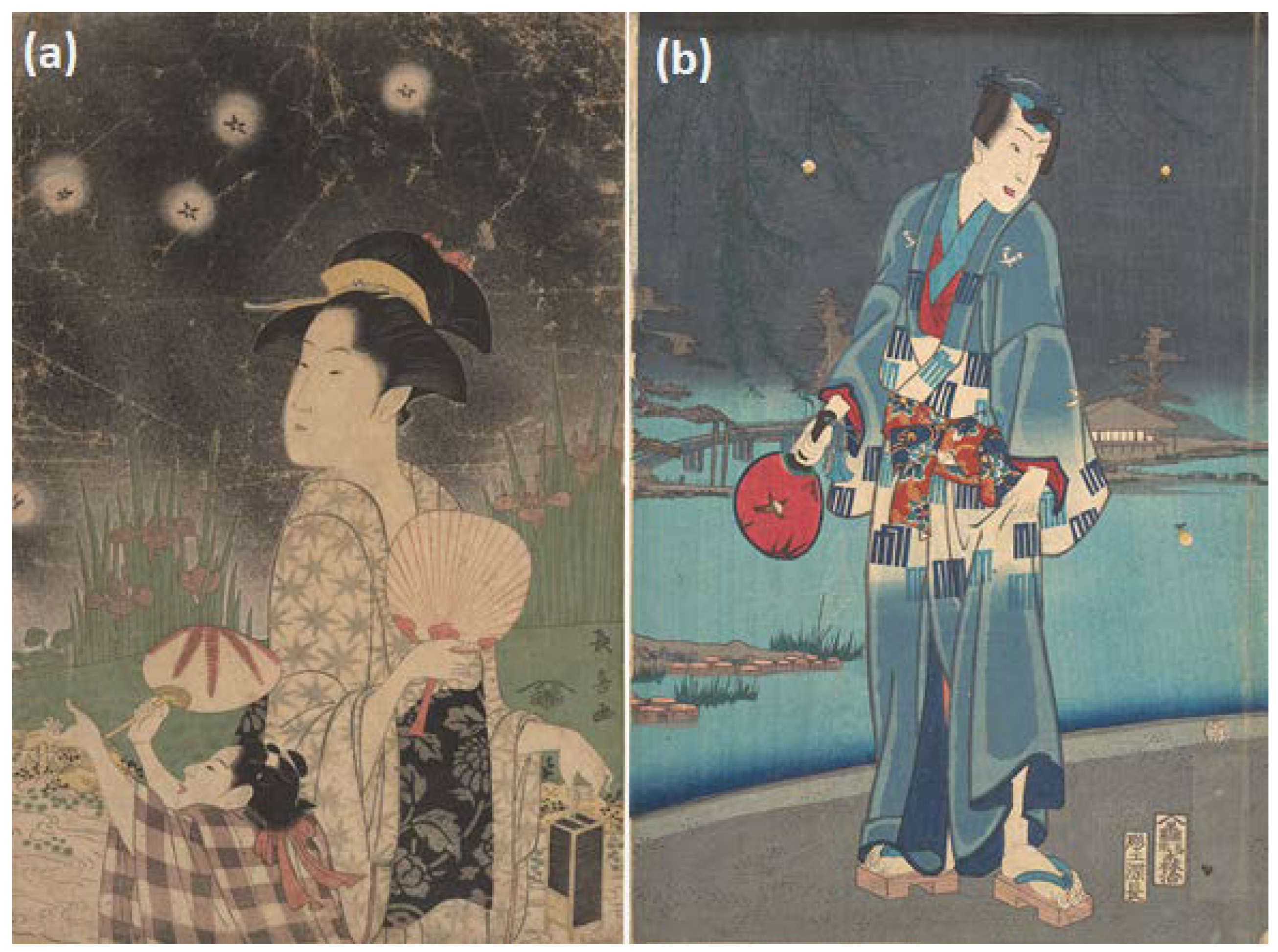

Information and websites for images referenced in this study are listed in the associated article published in Insects (https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13090775), with each work given a unique identification number. Artists depicted adult fireflies in the absence or presence of people. Representations of adults were diverse, whether free-ranging or contained within cages, and ranged from realistic-looking insects to yellow-colored or golden dots. Some fireflies appeared to be generalized insects or resembled butterflies, or were more abstract, such as a blotch or the letter ‘X’. However, in other pieces the insects were clearly fireflies. In general, the more accurate depictions of fireflies tended to be on artwork lacking people or on objects. Images of fireflies interacting with other animals were rare. Two-dimensional artwork focused solely on the insects fell into two broad categories. Several pieces, including multiple works by Zeshin, had a few non-glowing fireflies flying or at rest, usually outdoors in the daytime surrounded by white space or in still-lifes. A second group of paintings and prints depicted fireflies—often dozens of them—at night near water. These night scenes had muted gray or black color palettes, which highlighted the fireflies’ reddish body parts and luminescence (Figure 1).

3. People Represented in Artwork

References

- Hogue, C.L. Cultural entomology. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1987, 32, 181–199.

- Capinera, J.L. Insects in art and religion: The American southwest. Am. Entomol. 1993, 39, 221–230.

- Dicke, M. Insects in Western art. Am. Entomol. 2000, 46, 228–237.

- Dicke, M. From Venice to Fabre: Insects in western art. Proc. Neth. Entomol. Soc. Meet. 2004, 15, 9–15.

- Kritsky, G.; Mader, D.; Smith, J.J. Surreal entomology: The insect imagery of Salvador Dalí. Am. Entomol. 2013, 59, 28–37.

- Prischmann-Voldseth, D.A. Insects in art in the age of industry. In A Cultural History of Insects, Volume 5: A Cultural History of Insects in the Age of Industry; Anelli, C., Fisher, S., Kritsky, G., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, (accepted; in press).

- Wang, Y.D. Bioluminescence and 16th-Century Caravaggism: The Glowing Intersection between Art and Science; National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, University of Buffalo: Buffalo, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.nsta.org/ncss-case-study/bioluminescence-and-16th-century-caravaggism (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Tanabashi, S. STEAM education using sericulture ukiyo-e: Object-based learning through original artworks collected at a science university museum in Japan. IJESE 2021, 17, e2248.

- Klein, B.A.; Brosius, T. Insects in art during an age of environmental turmoil. Insects 2022, 13, 448.

- Lewis, S.M.; Wong, C.H.; Owens, A.; Fallon, C.; Jepsen, S.; Thancharoen, A.; Wu, C.; De Cock, R.; Novák, M.; López-Palafox, T.; et al. A global perspective on firefly extinction threats. BioScience 2020, 70, 157–167.

- Fallon, C.E.; Walker, A.C.; Lewis, S.; Cicero, J.; Faust, L.; Heckscher, C.M.; Pérez-Hernández, C.X.; Pfeiffer, B.; Jepsen, S. Evaluating firefly extinction risk: Initial red list assessments for North America. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259379.

- Ferreira, V.S.; Keller, O.; Branham, M.A. Multilocus phylogeny support the non-bioluminescent firefly Chespirito as a new subfamily in the Lampyridae (Coleoptera: Elateroidea). Insect Syst. Divers. 2020, 4, 2.

- Stanger-Hall, K.F.; Lloyd, J.E.; Hillis, D.M. Phylogeny of North American fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae): Implications for the evolution of light signals. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 45, 33–49.

- Lloyd, J.E. Firefly mating ecology, selection and evolution. In Evolution of Mating Systems in Insects and Arachnids; Choe, J.C., Crespi, B.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1997; pp. 184–192.

- Lloyd, J.E. Aggressive mimicry in Photuris: Firefly femmes fatales. Science 1965, 149, 653–654.

- Lloyd, J.E. Aggressive mimicry in Photuris fireflies: Signal repertoires by femmes fatales. Science 1975, 187, 452–453.

- Ohba, N. Flash communication systems of Japanese fireflies. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2004, 44, 225–233.

- Buschman, L.L. Light organs of immature fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) as eye-spot/false-head displays. Coleopt. Bull. 1988, 42, 94–97.

- Koji, S.; Nakamura, A.; Nakamura, K. Demography of the Heike firefly Luciola lateralis (Coleoptera: Lampyridae), a representative species of Japan’s traditional agricultural landscape. J. Insect Conserv. 2012, 16, 819–827.

- Laurent, E.L.; Ono, K. The firefly and the trout: Recent shifts regarding the relationship between people and other animals in Japanese culture. Anthrozoös 1999, 12, 149–156.

- Takeda, M.; Amano, T.; Katoh, K.; Higuchi, H. The habitat requirement of the Genji-firefly Luciola cruciata (Coleoptera: Lampyridae), a representative endemic species of Japanese rural landscapes. In Arthropod Diversity and Conservation; Hawksworth, D.L., Bull, A.T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 177–189.

- Haugan, E.B. Homeplace of the Heart: Fireflies, Tourism and Town-Building in Rural Japan. Master’s Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2019.

- Takada, K. Japanese interest in “Hotaru” (fireflies) and “Kabuto-Mushi” (Japanese rhinoceros beetles) corresponds with seasonality in visible abundance. Insects 2012, 3, 424–431.

- Hoshina, H. Cultural coleopterology in modern Japan, II: The firefly in Akihabara Culture. Ethnoentomol. 2018, 2, 14–19.

- Hoshina, H. The mythology of insect-loving Japan. Insects 2022, 13, 234.

- Takada, K. Popularity of different lampyrid species in Japanese culture as measured by Google search volume. Insects 2011, 2, 336–342.

- Oba, Y.; Branham, M.A.; Fukatsu, T. The terrestrial bioluminescent animals of Japan. Zool. Sci. 2011, 28, 771–789.

- Hearn, L. Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs; The Macmillan Company: London, UK, 1903.

- Hosaka, T.; Kurimoto, M.; Numata, S. An overview of insect-related events in modern Japan: Their extent and characteristics. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2016, 62, 228–234.

- Laurent, E.L. Mushi: For youngsters in Japan, the study of insects has been both a fad and a tradition. Nat. Hist. 2001, 110, 70–75.

- Kawahara, A.Y. Thirty-foot telescopic nets, bug-collecting video games, and beetle pets: Entomology in modern Japan. Am. Entomol. 2007, 53, 160–172.

- Kawahara, A.Y. Entomology in modern Japan: Pension Suzuran, the Japanese bug hotel. Am. Entomol. 2019, 65, 196–200.

- Folsom, J.W. Entomology: With Special Reference to Its Ecological Aspects, 3rd ed.; P. Blakiston’s Son & Co., Inc.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1922.

- Goldman, M. Fireflies. Mass. Rev. 1965, 6, 485–490.

- Maxim, G.W. Let the fun begin!: Dynamic social studies for the elementary school classroom. Child. Educ. 2003, 80, 2–5.

- Waldbauer, G. Fireflies, Honey, and Silk; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009.

- Lewis, S. Silent Sparks: The Wondrous World of Fireflies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016.

- Harris, F. Ukiyo-e: The Art of the Japanese Print; Tuttle Publishing: North Clarendon, VT, USA, 2010.

- Varley, H.P. Japanese Culture: A Short History; Praeger Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1977.