Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sigrid A Langhans | -- | 2456 | 2022-08-29 18:17:30 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 2456 | 2022-08-31 03:05:36 | | | | |

| 3 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 2456 | 2022-08-31 03:06:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Nikam, R.M.; Yue, X.; Kaur, G.; Kandula, V.; Khair, A.; Kecskemethy, H.H.; Averill, L.W.; Langhans, S.A. Pediatric Brain Tumors. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26634 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Nikam RM, Yue X, Kaur G, Kandula V, Khair A, Kecskemethy HH, et al. Pediatric Brain Tumors. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26634. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Nikam, Rahul M., Xuyi Yue, Gurcharanjeet Kaur, Vinay Kandula, Abdulhafeez Khair, Heidi H. Kecskemethy, Lauren W. Averill, Sigrid A. Langhans. "Pediatric Brain Tumors" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26634 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Nikam, R.M., Yue, X., Kaur, G., Kandula, V., Khair, A., Kecskemethy, H.H., Averill, L.W., & Langhans, S.A. (2022, August 29). Pediatric Brain Tumors. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26634

Nikam, Rahul M., et al. "Pediatric Brain Tumors." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 August, 2022.

Copy Citation

Central nervous system tumors are the most common pediatric solid tumors; they are also the most lethal. Unlike adults, childhood brain tumors are mostly primary in origin and differ in type, location and molecular signature. Tumor characteristics (incidence, location, and type) vary with age. Pediatric brain tumors are the most common solid tumors in children. Traditionally classified by location, age at presentation, and histological type, advances in molecular biology and genetics have allowed for more refined subgrouping within major tumor types.

pediatrics

brain tumor

imaging

1. Overview of Pediatric Brain Tumors

Given the major implications of molecular subgrouping for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, in 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a new framework for the classification of CNS tumors by integrating molecular and genetic profiling into diagnosis (Table 1) [1][2][3][4][5]. The fifth edition of the WHO classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System was recently published in 2021 and represents the sixth version of the international standard for the classification of brain and spinal cord tumors [6]. Similarly, the increasing ability of radiogenomics to correlate imaging features with underlying disease biology and the advent of deep machine learning are expected to significantly contribute to improving the accuracy of diagnosis, the prediction of disease outcomes, and therapeutic decision-making for children diagnosed with brain tumors.

Table 1. Pediatric brain tumors—an overview.

| Family | Tumor Type | Additional Subtyping Based on Molecular Alterations | Frequent Molecular Alterations (*) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS embryonal tumors | |||

| Medulloblastomas | WNT-activated | CTNNB1; often in conjunction with monosomy chromosome 6, DDX3X, SMARCA4, and TP53 mutations | |

| SHH-activated (wildtype TP53) | SHH-1, SHH-2, SHH-4 | PTCH1, SUFU, SMO | |

| SHH-activated with mutant TP53 | SHH-3 | TP53, MYCN amplification, GLI2 amplification | |

| Non-WNT/non-SHH (Group 3 and Group 4) | Subtypes 1-8 | MYC or MYC/MYCN amplification, GFI/GFI1B alterations, OTX2, CDK6 or SNCAP1 amplifications; isochromosome 17; PRDM6, KBDBD4 mutations | |

| Atypical teratoid/ rhabdoid tumors | ATRT-TYR, ATRT-SHH, ATRT-MYC | SMARCB1, SHH, NOTCH, loss of 22q, tyrosinase overexpression, MYC activation, HOXC | |

| Gliomas, glioneuronal and neuronal tumors | |||

| Diffuse high-grade gliomas |

Diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27-altered | H3.3 K27-mutant; H3.1 or H3.2 K27-mutant; H3 wildtype with EZHIP overexpression; EGFR (and H3 K27) mutant | Histone 3 mutations, TP53, PPM1D, PDGFRA, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, PTEN mutations, EZHIP overexpression, EGFR mutations |

| Diffuse hemispheric glioma, H3 G34-mutant | Histone 3 mutation, TP53, ATRX mutations | ||

| Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype | RTK1; RTK2; MYCN | Enriched for PDGFRA, EGFR or MYCN amplification | |

| Infant-type hemispheric glioma | NTRK-altered; ROS1-altered; ALK-altered; MET-altered | NTRK1/2/3 fusion; ROS1 fusion; ALK fusion; MET amplification/fusion | |

| Diffuse low-grade gliomas |

Diffuse astrocytoma | MYB-altered; MYBL1-altered | MYB fusion or MYBL fusion commonly with PCDHGA1, MMP16 and MAML2 |

| Angiocentric glioma | MYB alterations, commonly fused with QKI | ||

| Polymorphous low-grade neuroepithelial tumor | MAPK pathway–BRAF pV600E, fusions with FGFR2 or FGFR3 | ||

| Diffuse low-grade glioma, MAPK pathway-altered | FGFR1 tyrosine kinase domain-duplicated; FGFR1 mutant; BRAF pV600E-mutant | MAPK pathway–FGFR1; BRAF pV600E | |

| Astrocytic gliomas | Pilocytic astrocytoma | Pilomyxoid astrocytoma; pilocytic astrocytoma with histological features of anaplasia | KIA1549:BRAF fusion; NF1; BRAF p.V600E; FGFR1 mutation/fusion; KRAS; RAF1 or NTRK fusion |

| High-grade astrocytoma with piloid features | NF1; FGFR; BRAF:KIAA1549 fusion; often with homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/B | ||

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma | BRAF pV600E typically with homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/B | ||

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | |||

| Astroblastoma | MN1 fusion with BEND2 or CXXC5 | ||

| Glioneuronal/ neuronal tumors |

Ganglioglioma | Most commonly BRAF p.V600E mutation, other MAPK pathway alterations | |

| Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma/astrocytoma | BRAF or RAF1 fusions or mutations | ||

| Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor | FGFR1 mutation, fusion or intragenic duplication | ||

| Diffuse glioneuronal tumor with oligodendroglioma-like features and nuclear clusters | Monosomy of chromosome 14 | ||

| Diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumor | With 1qgain; methylation class 1; methylation class 2 | KIAA1549:BRAF fusion or other MAPK alteration, combined with 1p deletion | |

| Multinodular and vacuolating neuronal tumor | MAPK pathway | ||

| Ependymomas | Supratentorial ependymomas | ZFTA fusion-positive; YAP fusion-positive; additional molecular subgroups awaiting to be defined | ZFTA fusion most commonly with RELA; YAP1 fusion most commonly with MAMLD1 |

| Posterior fossa ependymomas | Group A (PFA); group B (PFB)-retained H3K27 trimethylation; additional molecular subgroups awaiting to be defined | Loss of H3K27 trimethylation, EZHIP overexpression | |

(*) Adapted from [6].

2. Medulloblastoma

Medulloblastoma, the most predominant malignant brain tumor in children, has been at the forefront of the molecular subgrouping of pediatric brain tumors (Figure 1). Originating from precursor cells in the cerebellum or dorsal brainstem, medulloblastoma is an embryonal tumor located in the posterior fossa and comprises up to 20% of all pediatric brain tumors [7]. Previously classified into four different histological groups (classic, desmoplastic/nodular, extensive nodularity, and large cell/anaplastic tumors), medulloblastoma has now been reclassified into four major groups incorporating both histology and molecular profiling. The present four distinct subgroups—wingless/integrated (WNT), sonic hedgehog (SHH), Group 3, and Group 4—have different underlying genetic alterations, distinct tumor biology, a diverse and wide range of phenotypes, and different patient outcomes [8]. Radiomic and machine learning approaches are currently being developed to predict the molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma by imaging [9].

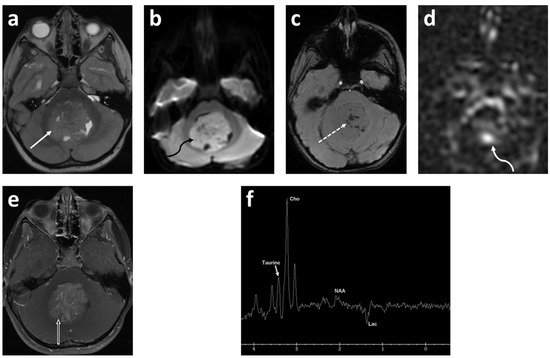

Figure 1. Five-year-old female presented with headache, vomiting and gait disturbance. Axial T2 (a); axial DWI (b); axial SWAN (c); axial ASL-PWI (d); axial T1 fat saturated post contrast (e) images; and long TE (144 msec) spectroscopy (f). There is a large heterogeneous, intermediate T2 signal mass centered in the fourth ventricle (solid white arrow). This mass demonstrates restricted diffusion (curved black arrow) with numerous punctate foci of the hemorrhage (dashed arrow) and increased perfusion (curved white arrow) in the center of the lesion. There is moderate heterogeneous enhancement after contrast ministration (open arrow). Spectroscopy demonstrates Taurine peak at 3.4 ppm, high choline (Cho) and undetectable N-acetylaspartate (NAA). There is also high lactate (Lac) demonstrated as an inverted peak on this long TE spectroscopy. Final diagnosis was medulloblastoma, Group 3 (author’s institutional human ethics committee/institutional review board guidelines were followed for anonymized images).

Tumors of the WNT subgroup occur mostly in older children, account for about 10% of medulloblastomas, are almost always of classic histology, and have the most favorable prognosis among all medulloblastoma subgroups. Named after the aberrant activation of the WNT signaling pathway caused by mutations of the CTNNB1 gene that encodes β-catenin, WNT tumors are also reported to have monosomy chromosome 6, usually in conjunction with CTNNB1 mutations and mutations in DDX3X, SMARCA4, and TP53 [2][3][4][5][8]. WNT medulloblastoma is thought to arise outside the cerebellum from cells of the dorsal brainstem, including the lower and upper rhombic lip [10]. Owing to this cellular origin, WNT medulloblastomas are typically located in the posterior fossa with approximately 75% of tumors occurring along the cerebellar peduncle and the cerebellopontine angle cistern, yielding an imaging finding that is predictive of this subgroup [11].

Comprising about 30% of medulloblastomas, SHH-driven tumors are the second most common subgroup. Mutations of signaling molecules within the SHH pathway, such as SUFU, smoothened (SMO), PTCH1, GLI1 and GLI2, are defining, and they are commonly sought after as prime targets for small molecule inhibitors in medulloblastoma drug discovery [2][3][4][5][8][12]. However, SHH tumors are indeed a highly heterogenous subgroup with varied histology ranging from classic to large cell/anaplastic and SHH subtype-specific desmoplastic/nodular medulloblastomas with extensive nodularity (MBEN). Like WNT tumors, the SHH subgroup often presents with additional mutations such as MYCN and TP53 that are defining for prognosis [13]. Because of this heterogeneity, the varying propensity to metastasize, and the varied outcomes that are also dependent on age, SHH medulloblastoma may be better defined by the following subtypes: SHHα, typically found in children with TP53 mutations; SHHβ, found in infants with poor prognosis; Shhγ, found in infants with good prognosis; and SHHΔ (or alternatively SHH1-4), tumors mostly found in adults [8][14][15] (Table 1) [6]. Originating from precursor cells of cerebellar granule neurons, SHH medulloblastomas are usually located in the cerebellar hemispheres but radiologically can also be found in the midline and then are essentially indistinguishable from Group 3 and Group 4 tumors [14].

Group 3 and Group 4 tumors are more heterogenous than WNT and SHH tumors and are still less well understood in terms of underlying genetic mutations and cells of origin. Group 3 medulloblastoma accounts for about 25% of medulloblastoma tumors and is a highly aggressive form with a propensity to metastasize. MYC amplification is frequently found in Group 3 medulloblastoma and is associated with an overall poor prognosis, but other pathways such as TNF (tumor necrosis factor)-β signaling can also be affected in tumors of this subgroup [3][4][5]. Group 4 medulloblastoma accounts for approximately 35% of tumors and, like Group 3, is biologically poorly characterized. The loss of chromosomes 8, 11 and 17p, or the gain of chromosomes 7 and 17q have been found, in addition to the amplification of CDK6, MYCN and SNCAP1 and aberrant ERBB4-SRC and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling [2][3][4][5][8][16][17]. Following the lead of the WNT and SHH subgroups in molecular and biological stratification, an international meta-analysis study has recently suggested that Group 3/4 may be further divided into eight subtypes (types 1–8) based on transcriptomes, DNA methylation profiling, and clinico-pathological features [6][18]. Because the radiographic features of Group 3 and Group 4 medulloblastomas are similar with midline masses arising from the vermis, advanced imaging methods are the most promising in delineating subgroup and subtype-specific characteristics for a radiological differential diagnosis of these tumors (Table 2).

| Imaging Characteristics |

Wnt | SHH | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Cerebellar peduncle/cerebellopontine angle | Cerebellar hemispheres | Midline/fourth ventricle | Midline/fourth ventricle |

| Post-contrast enhancement | Variable | Present, intense | Present | Variable, can be non-enhancing |

| Drop metastasis | Rare | Rare | Frequent | Frequent |

| MRS | - | Prominent choline and lipids, low creatine, no or small taurine peak | Readily detectable taurine and creatine levels | Readily detectable taurine and creatine levels |

3. Glioma

Gliomas are a group of highly heterogenous tumors that represent 47% of all pediatric brain tumor cases. Depending on the glial cell type of origin, gliomas are categorized into astrocytomas, ependymomas, oligodendrogliomas or astrocytic gliomas, and can range from rather benign low-grade gliomas (LGGs) to highly malignant high-grade tumors (HGGs) [4][6][7][21][22].

LGGs are the most common gliomas and are typically associated with the aberrant activation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. They tend to be slow-growing, benign tumors, and in children malignant transformation is uncommon. LGGs encompass a variety of histologically diverse neoplasms and include pilocytic astrocytoma (grade I), subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (grade I), IDH mutant diffuse astrocytoma (grade II), IDH mutant or 1p/19q deletion oligodendroglioma (grade II), pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (grade II), angiocentric glioma (grade I), choroid glioma of the third ventricle (grade I or II), gangliocytoma (grade I), ganglioglioma (grade I or II), desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma, and ganglioglioma (grade I) [23][24]. Mutations usually occur in the serine/threonine kinase B-Raf proto-oncogene (BRAF) within the RAS/MAPK pathway, and specific mutations can be associated with a certain tumor type. For example, KIAA1549:BRAF fusion is mostly found in pilocytic astrocytoma and the BRAF V600E mutation is frequently detected in pilomyxoid astrocytoma and gangliogliomas [25]. Other mutations such as kRAS, FGFR1, MYB/MYBL1, NTRK2, NF1, TSC1/2 and other genetic alteration have also been identified but, unlike in adults, IDH mutations are almost absent in pediatric LGGs [2][3][4][5][22][26][27]. Interestingly, recent studies have discovered some overlap in molecular profiling between LGG and HGG, and BRAF V600E and FGFR1 mutations can be found both in LGG and HGG [22][26], suggesting that LGG and HGG might share a similar biological mechanism of tumor pathogenesis. While LGGs are heterogenous, the spatial clustering of individual tumor phenotypes and the spatial enrichment of specific genetic mutations highlight the importance and potential of the radiohistogenomic profiling of LGGs [28].

HGGs are relatively uncommon pediatric gliomas (comprising 3–7% of all pediatric brain tumors), but they are highly aggressive and diffusely infiltrate malignant tumors yielding a very poor prognosis. They pose a serious challenge in pediatric oncology. Based on histological and radiological features, HGGs are subclassified into the following groups: anaplastic astrocytoma (grade III), IDH wild-type glioblastoma (grade IV), IDH-mutant glioblastoma (grade IV), H3K27M-mutant diffuse midline glioma (grade IV), IDH-mutant with 1p/19q co-deletion anaplastic oligodendroglioma (grade III), and pleomorphic anaplastic xanthoastrocytoma (grade III). Because of the therapeutic implications, genetic testing should be performed for IDH, BRAF (epithelioid glioblastoma), MYC (glioblastoma with PNET components), EGFR (small cell and granular glioblastoma) and H3K27M (diffuse midline glioma) [22][24][29]. Histone mutations may vary according to the location of the tumor. K27M mutations in H3F3A (encoding histone H3.3) or HIST1H3B/C (encoding histone H3.1) are very common in tumors arising from the midline and pons, while G34R (or rarely G34V) mutations in H3F3A (encoding histone H3.3) are mostly reported in hemispheric HGGs. In addition, the RTK/RAS/PI3K pathway (e.g., PDGFRA, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, or PTEN) and the p53/Rb pathway (e.g., TP53, CDKN2A, CDK4/6, CCND1-3) are also dysregulated in pediatric HGG [2][3][12][22][26][27][30][31] (Figure 2).

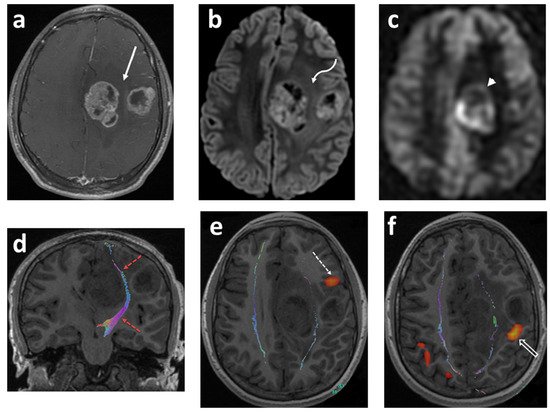

Figure 2. Fourteen-year-old boy with headaches and episodes of right facial and hand numbness. Axial T1 fat sat post contrast (a); axial DWI (b); axial ASL-PWI (c); coronal T1 tractography (d); and functional (e,f) images. There are two well-defined lobulated heterogeneously enhancing lesions within the posterior aspect of the left frontal lobe (solid white arrow). The lesions show restricted diffusion (curved white arrow) and increased perfusion (arrowhead). The cortical spinal tracts are identified tracking in between the two tumor masses (red–dashed arrows). The Broca’s area is identified in the left inferior frontal gyrus anterior and inferior to the lateral frontal mass lesion (dashed arrow). The motor cortex with right finger tapping is immediately posterior to the smaller mass in the lateral aspect of the left frontal lobe (open arrow). Pathology: giant cell glioblastoma (author’s institutional human ethics committee/institutional review board guidelines were followed for anonymized images).

4. Ependymoma

Ependymomas are the third most frequently occurring pediatric brain cancers and represent 5–10% of all childhood primary brain tumors [4][7]. Ependymomas are thought to originate from radial glial cells of the ependymal lining of the ventricles and the central canal. More than 90% of ependymomas arise in the infratentorial and supratentorial regions. Histologically, they are classified into four groups: subependymoma, myxopapillary ependymoma, classic ependymoma, and anaplastic ependymoma. Based on histological features, classic ependymoma is further subtyped into three groups: papillary, clear cell, and tanycytic ependymoma. Together, classic and anaplastic ependymoma are the most common subtypes in children [3][4]. Ependymomas can further be subclassified based on location and molecular features predictive of outcome. For example, Group A (PF-EPN-A) and Group B (PF-EPN-B) ependymomas are infratentorial posterior fossa (PF) tumors that differ in their DNA methylation profile. PF-EPN-A tumors are hypermethylated, mostly found in infants and young children, and yield a poorer outcome compared to PF-EPN-B tumors. Supratentorial (ST) ependymomas in children have two major subgroups: RELA fusion-positive (ST-EPN-RELA) ependymoma and YAP1 fusion-positive (ST-EPN-YAP1) ependymoma. ST-EPN-RELA usually harbors the fusion protein of C11orf95 and RELA and, in ST-EPN-YAP1 ependymoma, the transcriptional coactivator YAP1 fuses with other genes such as MAMLD1 and FAM118B, resulting in the upregulation of tumor promoting signaling pathways [2][3][4][5][32][33][34]. Like in other pediatric brain cancers, ependymoma location and molecular characteristics often correlate, highlighting the importance of tumor imaging in early and accurate diagnosis.

References

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; Von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820.

- Wells, E.M.; Packer, R.J. Pediatric Brain Tumors. Contin. Minneap. Minn. 2015, 21, 373–396.

- Dang, M.; Phillips, P.C. Pediatric Brain Tumors. Contin. Minneap. Minn. 2017, 23, 1727–1757.

- Udaka, Y.T.; Packer, R.J. Pediatric Brain Tumors. Neurol. Clin. 2018, 36, 533–556.

- Pollack, I.F.; Agnihotri, S.; Broniscer, A. Childhood brain tumors: Current management, biological insights, and future directions. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2019, 23, 261–273.

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251.

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Truitt, G.; Boscia, A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, iv1–iv86.

- Northcott, P.A.; Robinson, G.W.; Kratz, C.P.; Mabbott, D.J.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Clifford, S.C.; Rutkowski, S.; Ellison, D.W.; Malkin, D.; Taylor, M.D.; et al. Medulloblastoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 11.

- Iv, M.; Zhou, M.; Shpanskaya, K.; Perreault, S.; Wang, Z.; Tranvinh, E.; Lanzman, B.; Vajapeyam, S.; Vitanza, N.; Fisher, P.; et al. MR Imaging–Based Radiomic Signatures of Distinct Molecular Subgroups of Medulloblastoma. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 40, 154–161.

- Gibson, P.; Tong, Y.; Robinson, G.; Thompson, M.C.; Currle, D.S.; Eden, C.; Kranenburg, T.; Hogg, T.; Poppleton, H.; Martin, J.; et al. Subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinct developmental origins. Nature 2010, 468, 1095–1099.

- Patay, Z.; Desain, L.A.; Hwang, S.N.; Coan, A.; Li, Y.; Ellison, D.W.; April, A.C. MR Imaging Characteristics of Wingless-Type-Subgroup Pediatric Medulloblastoma. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2015, 36, 2386–2393.

- Lin, C.Y.; Erkek, S.; Tong, Y.; Yin, L.; Federation, A.J.; Zapatka, M.; Haldipur, P.; Kawauchi, D.; Risch, T.; Warnatz, H.-J.; et al. Active medulloblastoma enhancers reveal subgroup-specific cellular origins. Nature 2016, 530, 57–62.

- DeSouza, R.M.; Jones, B.R.; Lowis, S.P.; Kurian, K.M. Pediatric medulloblastoma—update on molecular classification driving targeted therapies. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 176.

- AlRayahi, J.; Zapotocky, M.; Ramaswamy, V.; Hanagandi, P.; Branson, H.; Mubarak, W.; Raybaud, C.; Laughlin, S. Pediatric Brain Tumor Genetics: What Radiologists Need to Know. Radio Graph. 2018, 38, 2102–2122.

- Huang, S.; Yang, J.-Y. Targeting the Hedgehog Pathway in Pediatric Medulloblastoma. Cancers 2015, 7, 2110–2123.

- Cavalli, F.M.; Remke, M.; Rampasek, L.; Peacock, J.; Shih, D.J.; Luu, B.; Garzia, L.; Torchia, J.; Nor, C.; Morrissy, A.S.; et al. Intertumoral Heterogeneity within Medulloblastoma Subgroups. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 737–754.e6.

- Neumann, J.E.; Swartling, F.J.; Schüller, U. Medulloblastoma: Experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 134, 679–689.

- Sharma, T.; Schwalbe, E.C.; Williamson, D.; Sill, M.; Hovestadt, V.; Mynarek, M.; Rutkowski, S.; Robinson, G.W.; Gajjar, A.; Cavalli, F.; et al. Second-generation molecular subgrouping of medulloblastoma: An international meta-analysis of Group 3 and Group 4 subtypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 309–326.

- Colafati, G.S.; Voicu, I.P.; Carducci, C.; Miele, E.; Carai, A.; Di Loreto, S.; Marrazzo, A.; Cacchione, A.; Cecinati, V.; Tornesello, A.; et al. MRI features as a helpful tool to predict the molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: State of the art. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2018, 11.

- Blüml, S.; Margol, A.S.; Sposto, R.; Kennedy, R.J.; Robison, N.J.; Vali, M.; Hung, L.T.; Muthugounder, S.; Finlay, J.L.; Erdreich-Epstein, A.; et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma identification using noninvasive magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuro-Oncology 2015, 18, 126–131.

- Blionas, A.; Giakoumettis, D.; Klonou, A.; Neromyliotis, E.; Karydakis, P.; Themistocleous, M.S. Paediatric gliomas: Diagnosis, molecular biology and management. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 251.

- Sturm, D.; Pfister, S.; Jones, D.T.W. Pediatric Gliomas: Current Concepts on Diagnosis, Biology, and Clinical Management. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2370–2377.

- Rudà, R.; Reifenberger, G.; Frappaz, D.; Pfister, S.M.; Laprie, A.; Santarius, T.; Roth, P.; Tonn, J.C.; Soffietti, R.; Weller, M.; et al. EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ependymal tumors. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 20, 445–456.

- Cosnarovici, M.M.; Cosnarovici, R.V.; Piciu, D. Updates on the 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Pediatric Tumors of the Central Nervous System—A systematic review. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2021, 94, 282–288.

- Penman, C.L.; Efaulkner, C.; Lowis, S.P.; Kurian, K.M. Current Understanding of BRAF Alterations in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Targeting in Pediatric Low-Grade Gliomas. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 54.

- Sturm, D.; Filbin, M.G. Gliomas in Children. Skull Base 2018, 38, 121–130.

- Ferris, S.P.; Hofmann, J.W.; Solomon, D.A.; Perry, A. Characterization of gliomas: From morphology to molecules. Virchows. Arch. 2017, 471, 257–269.

- Bag, A.K.; Chiang, J.; Patay, Z. Radiohistogenomics of pediatric low-grade neuroepithelial tumors. Neuroradiology 2021, 63, 1185–1213.

- Jones, C.; Karajannis, M.A.; Jones, D.T.W.; Kieran, M.W.; Monje, M.; Baker, S.J.; Becher, O.J.; Cho, Y.-J.; Gupta, N.; Hawkins, C.; et al. Pediatric high-grade glioma: Biologically and clinically in need of new thinking. Neuro-Oncology 2016, 19, 153–161.

- Modzelewska, K.; Boer, E.; Mosbruger, T.L.; Picard, D.; Anderson, D.; Miles, R.R.; Kroll, M.; Oslund, W.; Pysher, T.J.; Schiffman, J.D.; et al. MEK Inhibitors Reverse Growth of Embryonal Brain Tumors Derived from Oligoneural Precursor Cells. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 1255–1264.

- Diaz, A.K.; Baker, S.J. The Genetic Signatures of Pediatric High-Grade Glioma: No Longer a One-Act Play. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 24, 240–247.

- Pajtler, K.W.; Witt, H.; Sill, M.; Jones, D.T.; Hovestadt, V.; Kratochwil, F.; Wani, K.; Tatevossian, R.; Punchihewa, C.; Johann, P.; et al. Molecular Classification of Ependymal Tumors across All CNS Compartments, Histopathological Grades, and Age Groups. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 728–743.

- Khatua, S.; Ramaswamy, V.; Bouffet, E. Current therapy and the evolving molecular landscape of paediatric ependymoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 70, 34–41.

- Vitanza, N.A.; Partap, S. Pediatric Ependymoma. J. Child Neurol. 2016, 31, 1354–1366.

More

Information

Subjects:

Pediatrics

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

31 Aug 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No