Smart agroforestry (SAF) is a set of agriculture and silviculture knowledge and practices that is aimed at not only increasing profits and resilience for farmers but also improving environmental parameters, including climate change mitigation and adaptation, biodiversity enhancement, and soil and water conservation, while assuring sustainable landscape management. Indonesia has the third largest area of tropical forest as well as the second largest biodiversity and the second highest number of indigenous medicinal plants in the world. It covers 10% of the global tropical forest with 50% of the world’s biodiversity, flora, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, primates, and birds, and provides 25% of the medicinal plants for human health. Social Forestry is a sustainable forest management system implemented in state forests or private/customary forests by local or traditional indigenous communities as the main actors to improve well-being, environmental balance, and sociocultural dynamics in the form of village forests, community forestry, community plantation forests, traditional forests, and forestry partnerships. Social and economic perspectives on SF development received more attention than environmental perspectives. Economic opportunities are deemed to be the main benefit of social forestry, while social and environmental challenges seem to be the major barriers to implementation. Three main keys in the SF program are how to improve the institutional governance, forest governance, and business governance. SF management needs innovation, technology, and collaboration to provide broader benefits for communities in terms of forest land and the use of forest products.

1. History of Agroforestry and Social Forestry Development

Agroforestry and social forestry may be two inseparable terms. While agroforestry refers to land-use techniques by which woody plants are combined with agricultural crops or livestock to form ecological and economic interactions between various existing components

[1], social forestry emphasizes the strategy of strengthening the tenure of forest management by granting access and management rights over forest areas to local communities (MOEF regulation 9/2021). Social forestry prioritizes the application of agroforestry techniques in land management in order to achieve two main objectives, community welfare and forest resource sustainability. The implementation of agroforestry in SF has been highly encouraged, as it is believed to contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals

[1].

Although research on agroforestry began to be popular around the 1980s

[2], agroforestry has been practiced in Indonesia for a very long time. Farming systems that are known by local names, such as

parak,

pelak,

repong damar,

tembawang,

simpukng,

talun,

wono,

tenganan, and

amarasi in various regions, basically reflect agroforestry practices that have become part of community culture in land management

[1]. Local community wisdom has viewed the agroforestry system as a land management approach that can meet daily needs while proving to be able to conserve natural resources, including forests.

The concept of social forestry, on the other hand, was introduced in Indonesia in the 19th century. The Dutch colonial government in the late 1890s introduced the

taungya or

tumpangsari system in Java

[2]. The taungya system was a model of granting access (cultivation rights) to farmers over teak forest areas in Java. Farmers were allowed to cultivate food crops between young teak plants up to a certain plant age. Farmers could enjoy the results of their cultivation but were obligated to look after the young teak plants. More recently, initiated by the 8th World Forestry Congress in Jakarta, with the theme "Forests for People", community rights to forest resources have received greater attention among policy makers, bureaucrats, scholars, and forestry practitioners at the national level

[3]. The attention of these various groups was also triggered by the increasing tenurial conflict between local communities and the government and forest area permit holders in land uses.

Various initiatives to give the community a greater role in managing forest areas then emerged. Perum Perhutani, with the assistance of various donors in 1985, built 13 pilot models of social forestry in several areas in Java, while other pilot models were built around the early 1990s in South Kalimantan, South Sulawesi, and West Irian

[4]. Analyses of these pilot practices indicated that social forestry can potentially improve the welfare of forest-surrounding communities and resolve tenurial conflicts, but there are weaknesses in terms of equal rights (between community groups and Perum Perhutani) and a lack of community interest in investing in the long term, due to uncertain continuation of land management rights

[5][6].

With the establishment of the Directorate General of Land Rehabilitation and Social Forestry under the Ministry of Forestry (MoF) in the early 1990s, community involvement in forest area management began to receive better attention in terms of the policy and regulatory aspects. However, as stated in

[7], at that time, the government had not given forest management rights to the community. Forest management was still dominated by the “forest first” approach, where community involvement was more directed toward forest rehabilitation programs

[8]. The limited budget and human resources for the implementation of forest rehabilitation were the main considerations for community involvement in the management of the forest area, and as a result, the community’s tenurial rights to manage the forest area have not been fully granted.

Community involvement in the early era of social forestry programs can be seen from several introduced policies, such as HPH Bina Desa, Community Forestry, and People Plantation Forest

[9]. In 1995, the government introduced the Community Forestry (CF) program. In this program, the community was actively involved in forest management activities and obtained the right to use non-timber forest products (NTFPs). The CF management permit was determined based on a contract agreement between the applicant (individual, community group, or cooperative) and the local Provincial Environment and Forestry Service. Although the policy still focused on community activities in forest rehabilitation, the program was successfully implemented through the granting of CF concessions in the Nusa Tenggara region, with an area of approximately 92,000 ha

[10].

The concept of social forestry that is close to the current practice might have existed since 2003. At the International Conference on Livelihoods, Forests, and Biodiversity, at a series of Conference of Parties meetings in Bonn in 2003, the official representative of Indonesia introduced a social forestry program with a more comprehensive approach that included ideology, strategy, and implementation in the context of community empowerment in forest resource management. The program provided access for local communities to manage forest areas in order to improve their welfare and conserve forests at the same time

[9]. In 2006, the government launched the Community Plantation Forest (Hutan Tanaman Rakyat or HTR) program, which was linked to its efforts to alleviate poverty (propoor), create new jobs (projob), and increase economic growth (progrowth)

[11].

Subsequently, in 2015, the development of social forestry entered a new phase. The 2014–2019 Working Cabinet, led by President Joko Widodo, merged the Ministry of Forestry with the Ministry of Environment to become the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), and one of the Directorate Generals formed under the MoEF is the Directorate General of Social Forestry and Environmental Partnerships (DG PSKL). The establishment of DG PSKL in 2015 significantly accelerated SF development. Under the Nawa Cita program promoted by the Presidential Cabinet, the DG PSKL set a target for developing social forestry in Indonesia, covering an area of 12.7 million ha, through five SF schemes: community forestry, village forest, people plantation forest, private/customary forest, and forestry partnership

[12]. From the emerging ideas of SF up to 2014, the total established SF area was only around 0.4 million ha, while the current total established area reached 5.004 million ha

[13].

Similar to SF, agroforestry policies ideally should be well-organized and institutionalized. Many successful collective actions on forest and land management in Indonesia were associated with the implementation of good agroforestry practices by communities

[14]. In Indonesia, there are at least two ministries that have been pioneers in the development of agroforestry: the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) and the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA). Although the mandate of the MoEF is within the forest area and the MoA is more focused on areas outside forests, there are many overlapping areas on the ground that require close coordination between the two ministries.

Agroforestry has a potential role in increasing farmers’ income and sustainable landscape management

[15]. Forest ecosystem services significantly support community livelihoods and provide very important sources of livelihood for indigenous people

[16]. In other places, such as Paru Village Forest, West Sumatra Province, community plantations of rattan within the agroforestry model show promise as a source of economic income

[17]. The application of best practices of agroforestry in SF areas seems promising to reduce people’s dependence on expanding the opening of forest lands, and thus could be a better alternative for reducing deforestation as well

[18][19]. Last but not least, the integration of the market chain is also among the crucial priorities in developing best practices of agroforestry

[20].

2. Rules and Regulation

The legal system in Indonesia has a clear hierarchical structure for its rules and regulations, including the Constitution, laws, government regulations, ministerial regulations, and regulations of the Director Generals. The regulatory hierarchy covers everything from philosophical principles to tactical and technical aspects of the implementation of government policies and programs. The system of rules and regulations applied to the agroforestry and social forestry sectors also follows this legal system.

Four main laws are used as reference rules for implementing agroforestry and SF: Law 41/1999 on forestry

[21], Law 32/2009 on environmental protection and management

[22], Law 37/2014 on soil and water conservation

[23], and Law 11/2020 on job creation

[23]. Observing the substance of the four laws, what is interesting is that three of them, Laws 41/1999, 32/2009, and 37/2014, seem to be in a diametrically opposite position to Law 11/2021. On the one hand, the three laws regulate how forests and land are managed, with a strong sense of ecological protection, while on the other hand, the law on job creation encourages investment for economic purposes. Based on this situation, implementing SAF becomes important and strategic as a counterbalance to achieving the mandate of the four laws. On the one hand, it ensures that the mandates of Laws 41/1999, 32/2009, and 37/2014 can be fulfilled, while at the same time ensuring that the objectives of Law 11/2021 regarding investment and job creation can also be fulfilled. What then becomes important is how the derivative regulations of the four laws can regulate and provide a legal umbrella for the implementation of SAF as a balance between the two poles of interest.

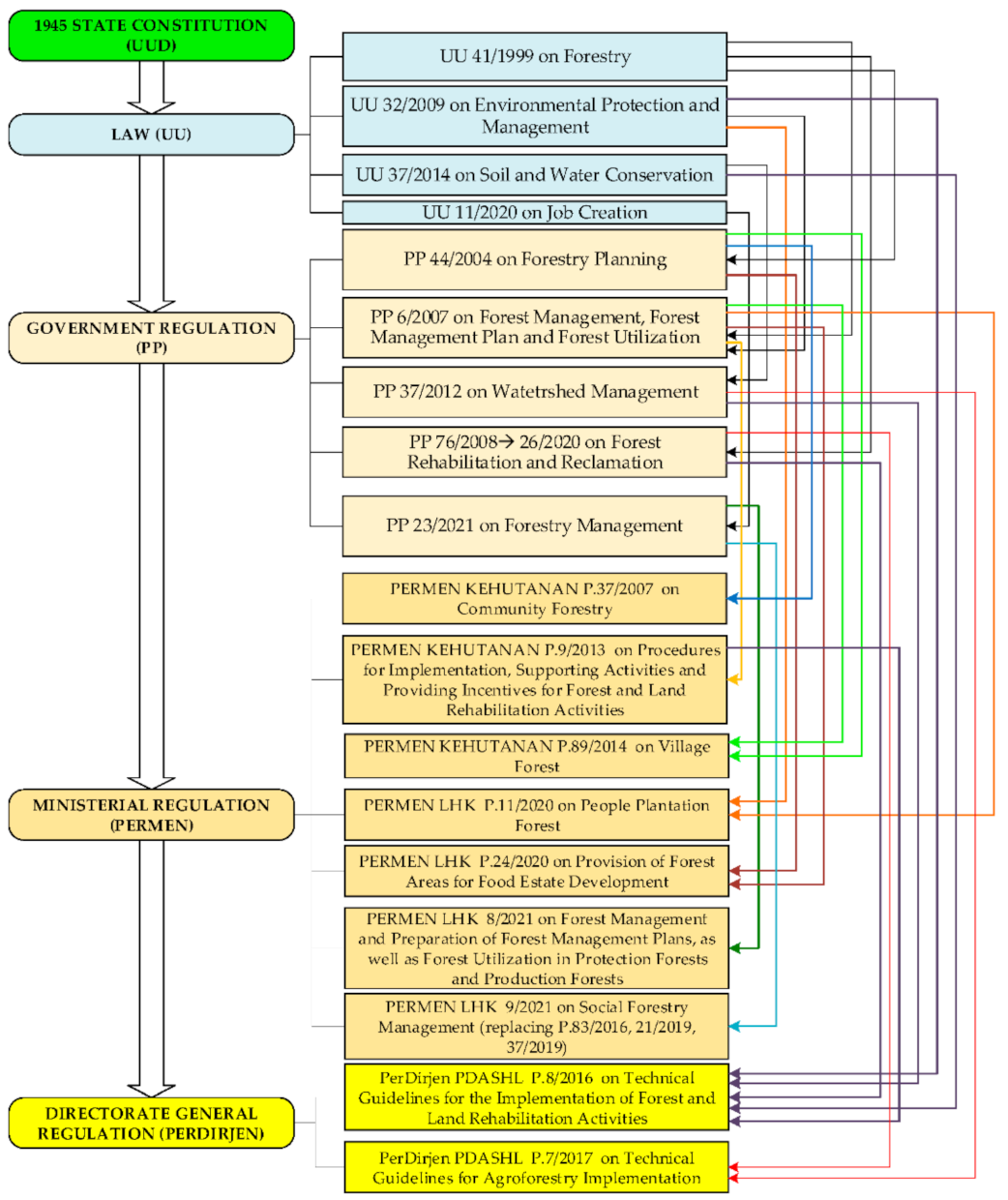

Under these laws, there are various government regulations (PP) that are the source of various derivative regulations focusing on agroforestry and SF. Some of the most relevant rules and regulations around agroforestry and social forestry are presented in

Figure 1. They include PP 26/2020 on forest rehabilitation and reclamation and PP 23/2021, concerning the implementation of forestry, which states that agroforestry is a form of reforestation (rehabilitation in forest areas) and afforestation (land rehabilitation outside forest areas)

[24]. AF is one of the recommended activities in the business of utilizing protected and production forests, as well as SF management

[25].

Figure 1. Regulations related to agroforestry and SF at the operational level and their umbrella rules (box colors indicate different rule levels and arrow colors indicate derivative rules).

The job creation law changes a number of regulations in the forestry sector. PP 23/2021 states that the management of social forestry is carried out by planting patterns in agroforestry, silvopasture, silvofishery, and agrosilvopasture. The regulation also states that village forest, community forestry, and people plantation forest approval holders are prohibited from planting oil palm trees in the SF concession area. PP 24/2021 regulates the term for managing oil palm plantations (jangka benah sawit) in forest areas that do not have permits in the forestry sector. The previous monoculture oil palm cultivation system must be gradually changed to an agroforestry system to increase land productivity and maintain biodiversity. Oil palm plantations are obliged to return the business part of the forest area to the state 25 years after planting. These two government regulations prove that the Indonesian government prevents forest conversion and encourages the application of agroforestry as a means of conflict resolution.

At the ministerial regulation level, PERMEN Kehutanan P.37/2007, which accommodates agroforestry practice in community forestry, seems to be the first ministerial regulation that mentions wanatani/agroforestry directly. Other regulations on agroforestry include P.11/2020 concerning people plantation forest and P.9/2021 on SF management. PERMEN LHK P.11/2020 regulates the application of agroforestry in cultivated areas based on the principle of sustainability. P.9/2021, concerning SF management, states that it can be carried out with agroforestry, silvopasture, silvofishery, and agrosilvopasture according to forest function and type of space

[26]. At the policy level, the two PPs and three PERMENs mentioned above, although some were enacted before Law 11/2021, provide a fairly strong legal basis for the implementation of SAF in Indonesia.

At the operational level, there are two regulations governing agroforestry, Director General of Watershed Control and Protected Forests (PerDirjen PDASHL) Regulation P.7/2017 concerning technical guidelines for agroforestry implementation, and P.8/2016, concerning technical guidelines for the implementation of forest and land rehabilitation activities. Perdirjen PDASHL P.8/2016 stipulates that agroforestry is a form of forest and land rehabilitation activities on cultivated land and forest areas. The technical guidance is further regulated in PERDIRJEN PDASHL P.7/2017 for implementing agroforestry in protected forests and outside forest areas, as a technical direction for agroforestry activities. The goal is to realize sustainable forest management and increase the carrying capacity of watersheds through agroforestry, for the welfare of the community in terms of economic, ecological, and social aspects

[27].

The support of two existing PERDIRJEN as operational guidelines for the implementation of SAF as a derivative of the ministerial regulations, PPs, and the above laws, could become the basis for implementing SAF to improve community welfare while assuring the continuation of the ecological functions of forests and land.