Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raffaella Casolino | -- | 1723 | 2022-08-11 12:04:50 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -3 word(s) | 1720 | 2022-08-11 12:12:53 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Casolino, R.; Corbo, V.; Beer, P.; Hwang, C.; Paiella, S.; Silvestri, V.; Ottini, L.; Biankin, A.V. Germline Aberrations in Pancreatic Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26071 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Casolino R, Corbo V, Beer P, Hwang C, Paiella S, Silvestri V, et al. Germline Aberrations in Pancreatic Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26071. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Casolino, Raffaella, Vincenzo Corbo, Philip Beer, Chang-Il Hwang, Salvatore Paiella, Valentina Silvestri, Laura Ottini, Andrew V. Biankin. "Germline Aberrations in Pancreatic Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26071 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Casolino, R., Corbo, V., Beer, P., Hwang, C., Paiella, S., Silvestri, V., Ottini, L., & Biankin, A.V. (2022, August 11). Germline Aberrations in Pancreatic Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26071

Casolino, Raffaella, et al. "Germline Aberrations in Pancreatic Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 August, 2022.

Copy Citation

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) has an extremely poor prognosis and represents a major public health issue, as both its incidence and mortality are expecting to increase steeply over the next years. Effective screening strategies are lacking, and most patients are diagnosed with unresectable disease precluding the only chance of cure. Therapeutic options for advanced disease are limited, and the treatment paradigm is still based on chemotherapy, with a few rare exceptions to targeted therapies. Germline variants in cancer susceptibility genes—particularly those involved in mechanisms of DNA repair—are emerging as promising targets for PDAC treatment and prevention.

germline

pancreatic cancer

BRCA

PARP inhibitors

1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a malignant disease with an extremely poor prognosis [1][2]. Both incidence and mortality continue to rise, and PDAC is predicted to soon become the second leading cause of cancer-related death [3][4]. Major efforts in improving surgical outcomes and progress in therapeutic development have only marginally increased the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of patients with PDAC over the past 5 decades, and is still less than 10% [3]. Much still needs to be improved to impact the burden of this disease. Currently, most patients (up to 80%) are diagnosed with unresectable disease due to non-specific symptoms and a lack of effective screening strategies. Earlier diagnosis may potentially improve outcomes since surgical resection is the only chance of cure [5]. As a consequence, the identification of biomarkers for early detection is an urgent priority. Patients with advanced tumors are treated with chemotherapy with an unselected approach, either in the neoadjuvant or metastatic setting. The most effective combinatorial regimens, based on phase III clinical trials, i.e., FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) and nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, only marginally improve the OS of patients, which rarely exceeds one year [6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]. After progression, less than 50% of patients are eligible for further treatments due to the rapid clinical deterioration typical of this disease. Second-line treatments have a very limited impact on clinical and survival outcomes, and clinical trials remain the optimal therapeutic choice in this setting [14].

2. Germline Variants and PDAC Susceptibility

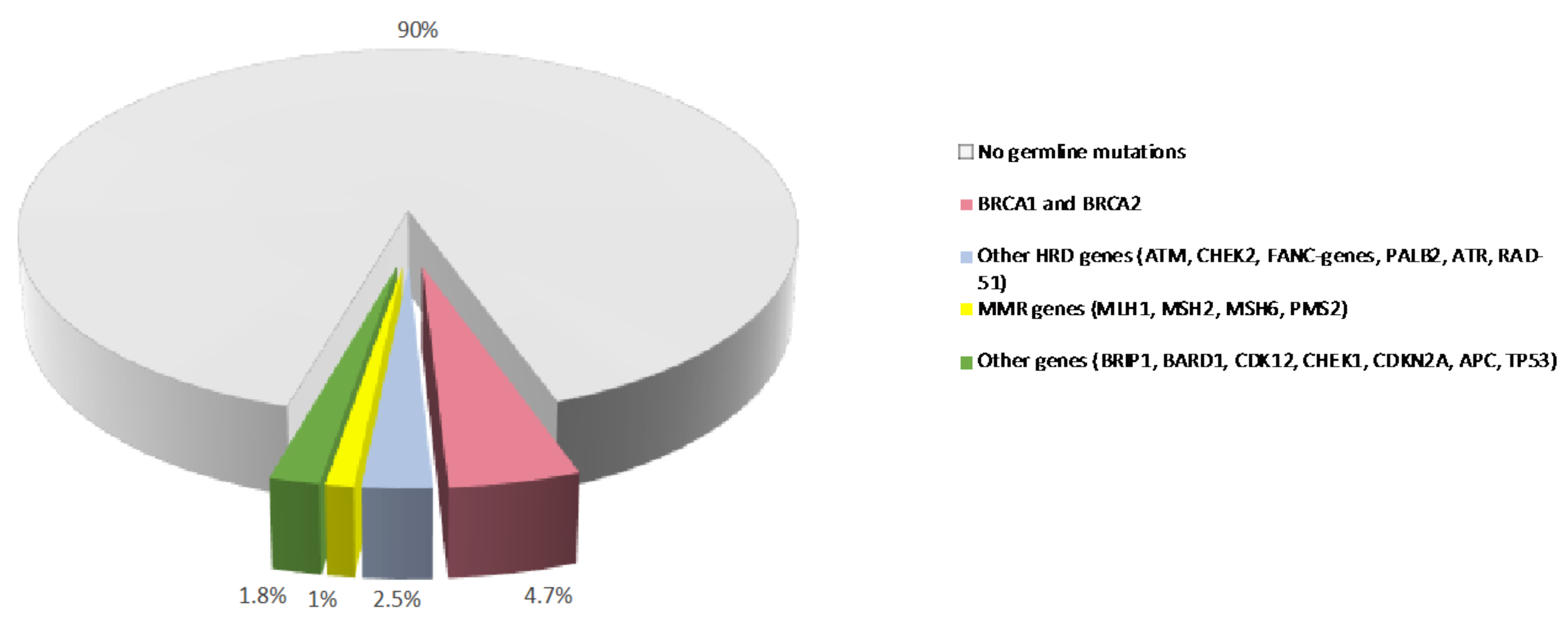

In contrast to somatic mutations, which are acquired during life and arise specifically in tumors, germline variants can be passed from parents to offspring and are associated with hereditary cancer syndromes. Germline pathogenic/likely-pathogenic variants in cancer predisposing genes are prevalent molecular alterations in PDAC (Figure 1) [15][16]. Several studies have shown that 3.8% to 9.7% of patients with PDAC carry a pathogenic germline mutation in genes that predispose them to hereditary cancer syndromes, including familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (CDKN2A), Peutz-Jeghers (STK11), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, ATM), Lynch (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6), and Li-Fraumeni (TP53) syndromes [17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. In some large single-center datasets, the prevalence of these alterations is as high as 19.8% [25]. Germline deleterious variants in the hereditary pancreatitis genes PRSS1 and SPINK1 also confer an increased risk of PDAC [26].

Figure 1. Prevalence of germline variants in PDAC. Prevalence of germline mutations in PDAC patients from published studies. MMR: mismatch repair. HR: homologous recombination.

Compared with a risk of about 1.5% in the general population, carriers of pathogenic variants in CDKN2A and STK11 have a higher lifetime risk of developing PDAC, which is estimated to be more than 15%. Carriers of pathogenic variants in the breast cancer genes BRCA2, ATM, and PALB2 have a moderate lifetime risk, ranging from 5% to 10%, whereas pathogenic variants in BRCA1 are estimated to confer a lower risk (less than 5%) [27]. More recently, data from a large international consortium of families with hereditary cancer syndromes associated with BRCA germline mutations demonstrated that the relative risk (RR) of PDAC was 2.36 (95% CI, 1.51–3.68) for BRCA1 and 3.34 (95% CI, 2.21–5.06) for BRCA2. The absolute risk of PDAC to age 80 was approximately 2.5% (for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers) [28]. Pathogenic variants in Lynch syndrome genes and TP53 are estimated to confer a moderate pancreatic cancer lifetime risk of about 5–10% [29].

A family history of PDAC also confers an increased risk. Patients with one or more first-degree relatives affected by PDAC are considered familial pancreatic cancer (FPC) cases [30]. In general, in the presence of a first-degree relative family history, the risk of developing PDAC increases with the number of affected relatives (by up to 4, 6, and 32 times for 1, 2, and 3 or more affected relatives, respectively) [31]. Overall, 80–90% of FPC cases are not attributable to a known genetic cause, suggesting the presence of additional genetic factors involved in PDAC susceptibility that have not yet been identified.

The recent broad use of cancer predisposing gene panel testing in clinical practice has allowed for the identification of pathogenic variants in a larger number of candidate cancer susceptibility genes, and also in patients without a family history, the so-called sporadic cases, with mutation rates varying among studies [15][32][33][34]. These findings have supported the current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommendation of performing extended genetic testing on all patients with a diagnosis of PDAC, regardless of family history or age of onset. Genetic testing should be performed with a comprehensive multi-gene panel, including, at a minimum, the genes ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, EPCAM, PALB2, STK11, and TP53 [29].

The opportunity for extended and universal genetic testing as a standard of care or in the research setting is expanding the probability of identifying clinically actionable germline variants in many genes, but their association with increased risk of PDAC is still uncertain. Indeed, a limited number of proposed candidate susceptibility genes have been consistently associated with an increased risk of PDAC, both in familial and sporadic cases [35][36]. For instance, there is no robust evidence suggesting a significant increased risk of PDAC in mutation carriers of CHEK2 pathogenic variants [36], although these variants are frequently observed in PDAC patients [15]. Overall, the rarity of pathogenic variants makes it very challenging to define reliable population-based risk estimates, and much larger studies are warranted. Targeted sequencing using comprehensive cancer gene panels may represent the best way to accumulate data to improve the genetic risk assessment for known-candidate genes. On the other hand, a broader genomic approach using whole exome sequencing or whole genome sequencing in selected high-risk families may help define “missing heritability” in PDAC.

As for most complex diseases, the role of low-penetrance common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) has been investigated in PDAC using genome-wide association studies (GWAS). According to the GWAS catalogue (accessed May 2021), a total of 200 associations with pancreatic risk were reported; however, few loci reached GWAS statistical significance at a p-value threshold of 5 × 10−8 and was consistently replicated among many studies (reviewed elsewhere [37]). To date, GWAS-identified loci have been estimated to explain about 4% of the phenotypic variation of PDAC; however, more associated SNPs (up to 1750) are expected to be discovered using larger study populations [25][38]. Since each common variant has a small impact on cancer risk, a polygenic architecture, in which many variants that confer low risk individually act in combination to confer much larger risk in the population, has been suggested as a model of cancer susceptibility. Polygenic risk scores (PRS), developed including GWAS identified loci, and multifactorial risk scores (MRS), developed combining genetic and non-genetic risk factors, were recently shown to improve risk prediction in patients with PDAC [39][40][41]. However, the clinical implementation of these models has yet to be established and deserves further assessment.

3. Preclinical and Translational Research in Hereditary PDAC

Preclinical and translational research is essential to improve the understanding of PDAC susceptibility and to facilitate the development of therapeutic strategies for patients with germline mutations. While approximately 10% of PDAC patients may harbor germline mutations, only a few pre-clinical models are commercially available in this field. CAPAN1 is the most commonly used BRCA2-deficient PDAC cell line, harboring BRCA2 c.6774delT truncating mutation [42]. In addition, PL11 and Hs766T harbor genetic alterations in the Fanconi anemia pathway genes FANCC (null mutation) and FANCG (nonsense mutation), respectively [43]. There are no detailed genomic annotations associated with commercially available PDAC cell lines or other preclinical models, and this hampers the preclinical usage of PDAC cell lines in the context of FPC. Genetically engineered mouse models have been critical for basic PDAC research and the preclinical evaluation of therapeutic strategies. One of the representative PDAC GEMM is the KPC mouse model, which harbors oncogenic KRAS G12D and a gain-of-function p53 R172H or R270H mutation (equivalent to human TP53 R175H or R273H) or p53 null mutation specifically in pancreatic epithelial cells driven by a Pdx1-Cre or Ptf1-Cre transgenic allele [44][45]. Since KRAS and TP53 mutations are the most common genetic alterations in PDAC, putative tumor suppressors or oncogenes have been modeled in the Kras mutant background or Kras/Trp53 double mutant background (reviewed by Guerra and Barbacid [46]). Although many genes are associated with hereditary PDAC, a few genes have been experimentally shown to contribute to PDAC progression in vivo using GEMM. Among cancer predisposing genes, mutations in BRCA2 and ATM play a role in PDAC progression [47][48], whilst the role of other genes remains to be defined. One of the challenges in modeling hereditary PDAC with GEMM is that the generation of conditional knockout alleles for individual cancer predisposing genes is time-consuming. In addition, PDAC mouse models need to be crossed with multiple oncogenic alleles, such as Kras mutations and pancreas-specific Cre alleles. Another critical issue related to hereditary PDAC is that genetic mutations are introduced at the embryonic development stage, which complicates the question of whether cancer predisposing genes play a role in the inception of key driver mutations, such as oncogenic mutations in KRAS in other tumor suppressors. Available GEMMs only allow us to address whether these mutations in cancer predisposing genes can cooperate with oncogenic Kras mutations or other driver mutations for PDAC progression.

In conclusion, various preclinical models of human PDAC are available for basic and translational research, including PDAC cell lines, patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), and patient-derived organoids (PDOs) [49]. Each preclinical model has its own advantages and disadvantages. Thus, the optimal model for each study should be determined based on specific scientific and clinical questions. To evaluate the efficacy of PARPi and other therapies for PDAC patients, a lack of detailed genomic annotations in the currently existing preclinical models is an issue that needs to be addressed. The use of isogenic cell lines or other preclinical models with CRISPR or other genetic engineering approaches is ideal for addressing a mutation-specific drug response in hereditary PDAC. In this way, the possibility of confounding effects that may come from other genetic mutations or other backgrounds can be excluded. In addition, the use of preneoplastic cells (e.g., PanIN-derived organoids) could be useful to address the effect of cancer predisposing gene mutations in the early stage of PDAC progression without generating new GEMM for hereditary PDAC [50].

References

- Landman, A.; Feetham, L.; Stuckey, D. Working together to reduce the burden of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 334–335.

- Huang, J.; Lok, V.; Ngai, C.H.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, J.; Lao, X.Q.; Ng, K.; Chong, C.; Zheng, Z.J.; Wong, M.C.S. Worldwide Burden of, Risk Factors for, and Trends in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 744–754.

- Rahib, L.; Wehner, M.R.; Matrisian, L.M.; Nead, K.T. Estimated Projection of US Cancer Incidence and Death to 2040. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e214708.

- Gaddam, S.; Abboud, Y.; Oh, J.; Samaan, J.S.; Nissen, N.N.; Lu, S.C.; Lo, S.K. Incidence of Pancreatic Cancer by Age and Sex in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA 2021, 326, 2075–2077.

- Gillen, S.; Schuster, T.; Meyer Zum Buschenfelde, C.; Friess, H.; Kleeff, J. Preoperative/neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of response and resection percentages. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000267.

- Nevala-Plagemann, C.; Hidalgo, M.; Garrido-Laguna, I. From state-of-the-art treatments to novel therapies for advanced-stage pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 108–123.

- Conroy, T.; Hammel, P.; Hebbar, M.; Ben Abdelghani, M.; Wei, A.C.; Raoul, J.L.; Chone, L.; Francois, E.; Artru, P.; Biagi, J.J.; et al. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2395–2406.

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouche, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Becouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; de la Fouchardiere, C.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1817–1825.

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1691–1703.

- Oettle, H.; Riess, H.; Stieler, J.M.; Heil, G.; Schwaner, I.; Seraphin, J.; Gorner, M.; Molle, M.; Greten, T.F.; Lakner, V.; et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: Outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2423–2429.

- Wang-Gillam, A.; Li, C.P.; Bodoky, G.; Dean, A.; Shan, Y.S.; Jameson, G.; Macarulla, T.; Lee, K.H.; Cunningham, D.; Blanc, J.F.; et al. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): A global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 545–557.

- Golan, T.; Hammel, P.; Reni, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Macarulla, T.; Hall, M.J.; Park, J.O.; Hochhauser, D.; Arnold, D.; Oh, D.Y.; et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 317–327.

- Moore, M.J.; Goldstein, D.; Hamm, J.; Figer, A.; Hecht, J.R.; Gallinger, S.; Au, H.J.; Murawa, P.; Walde, D.; Wolff, R.A.; et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1960–1966.

- Tempero, M.A.; Malafa, M.P.; Al-Hawary, M.; Behrman, S.W.; Benson, A.B.; Cardin, D.B.; Chiorean, E.G.; Chung, V.; Czito, B.; Del Chiaro, M.; et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 439–457.

- Casolino, R.; Paiella, S.; Azzolina, D.; Beer, P.A.; Corbo, V.; Lorenzoni, G.; Gregori, D.; Golan, T.; Braconi, C.; Froeling, F.E.M.; et al. Homologous Recombination Deficiency in Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review and Prevalence Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2617–2631.

- Gardiner, A.; Kidd, J.; Elias, M.C.; Young, K.; Mabey, B.; Taherian, N.; Cummings, S.; Malafa, M.; Rosenthal, E.; Permuth, J.B. Pancreatic Ductal Carcinoma Risk Associated with Hereditary Cancer-Risk Genes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, djac069.

- Jones, S.; Hruban, R.H.; Kamiyama, M.; Borges, M.; Zhang, X.; Parsons, D.W.; Lin, J.C.; Palmisano, E.; Brune, K.; Jaffee, E.M.; et al. Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science 2009, 324, 217.

- Roberts, N.J.; Jiao, Y.; Yu, J.; Kopelovich, L.; Petersen, G.M.; Bondy, M.L.; Gallinger, S.; Schwartz, A.G.; Syngal, S.; Cote, M.L.; et al. ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 41–46.

- Grant, R.C.; Selander, I.; Connor, A.A.; Selvarajah, S.; Borgida, A.; Briollais, L.; Petersen, G.M.; Lerner-Ellis, J.; Holter, S.; Gallinger, S. Prevalence of germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 556–564.

- Zhen, D.B.; Rabe, K.G.; Gallinger, S.; Syngal, S.; Schwartz, A.G.; Goggins, M.G.; Hruban, R.H.; Cote, M.L.; McWilliams, R.R.; Roberts, N.J.; et al. BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and CDKN2A mutations in familial pancreatic cancer: A PACGENE study. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 569–577.

- Macklin, S.K.; Kasi, P.M.; Jackson, J.L.; Hines, S.L. Incidence of Pathogenic Variants in Those with a Family History of Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 330.

- Mocci, E.; Guillen-Ponce, C.; Earl, J.; Marquez, M.; Solera, J.; Salazar-Lopez, M.T.; Calcedo-Arnaiz, C.; Vazquez-Sequeiros, E.; Montans, J.; Munoz-Beltran, M.; et al. PanGen-Fam: Spanish registry of hereditary pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 1911–1917.

- Giardiello, F.M.; Brensinger, J.D.; Tersmette, A.C.; Goodman, S.N.; Petersen, G.M.; Booker, S.V.; Cruz-Correa, M.; Offerhaus, J.A. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 1447–1453.

- Roberts, N.J.; Norris, A.L.; Petersen, G.M.; Bondy, M.L.; Brand, R.; Gallinger, S.; Kurtz, R.C.; Olson, S.H.; Rustgi, A.K.; Schwartz, A.G.; et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Defines the Genetic Heterogeneity of Familial Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 166–175.

- Chen, F.; Childs, E.J.; Mocci, E.; Bracci, P.; Gallinger, S.; Li, D.; Neale, R.E.; Olson, S.H.; Scelo, G.; Bamlet, W.R.; et al. Analysis of Heritability and Genetic Architecture of Pancreatic Cancer: A PanC4 Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1238–1245.

- Rebours, V.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Schnee, M.; Ferec, C.; Maire, F.; Hammel, P.; Ruszniewski, P.; Levy, P. Risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in patients with hereditary pancreatitis: A national exhaustive series. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 111–119.

- Zhan, W.; Shelton, C.A.; Greer, P.J.; Brand, R.E.; Whitcomb, D.C. Germline Variants and Risk for Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review and Emerging Concepts. Pancreas 2018, 47, 924–936.

- Li, S.; Silvestri, V.; Leslie, G.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Neuhausen, S.L.; Hopper, J.L.; Nielsen, H.R.; Lee, A.; Yang, X.; McGuffog, L.; et al. Cancer Risks Associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 Pathogenic Variants. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, JCO2102112.

- Daly, M.B.; Pal, T.; Berry, M.P.; Buys, S.S.; Dickson, P.; Domchek, S.M.; Elkhanany, A.; Friedman, S.; Goggins, M.; Hutton, M.L.; et al. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 77–102.

- Petersen, G.M. Familial pancreatic cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2016, 43, 548–553.

- Klein, A.P.; Brune, K.A.; Petersen, G.M.; Goggins, M.; Tersmette, A.C.; Offerhaus, G.J.; Griffin, C.; Cameron, J.L.; Yeo, C.J.; Kern, S.; et al. Prospective risk of pancreatic cancer in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2634–2638.

- Shindo, K.; Yu, J.; Suenaga, M.; Fesharakizadeh, S.; Cho, C.; Macgregor-Das, A.; Siddiqui, A.; Witmer, P.D.; Tamura, K.; Song, T.J.; et al. Deleterious Germline Mutations in Patients with Apparently Sporadic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3382–3390.

- Hu, C.; LaDuca, H.; Shimelis, H.; Polley, E.C.; Lilyquist, J.; Hart, S.N.; Na, J.; Thomas, A.; Lee, K.Y.; Davis, B.T.; et al. Multigene Hereditary Cancer Panels Reveal High-Risk Pancreatic Cancer Susceptibility Genes. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–28.

- Brand, R.; Borazanci, E.; Speare, V.; Dudley, B.; Karloski, E.; Peters, M.L.B.; Stobie, L.; Bahary, N.; Zeh, H.; Zureikat, A.; et al. Prospective study of germline genetic testing in incident cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2018, 124, 3520–3527.

- Chaffee, K.G.; Oberg, A.L.; McWilliams, R.R.; Majithia, N.; Allen, B.A.; Kidd, J.; Singh, N.; Hartman, A.R.; Wenstrup, R.J.; Petersen, G.M. Prevalence of germ-line mutations in cancer genes among pancreatic cancer patients with a positive family history. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 119–127.

- Hu, C.; Hart, S.N.; Polley, E.C.; Gnanaolivu, R.; Shimelis, H.; Lee, K.Y.; Lilyquist, J.; Na, J.; Moore, R.; Antwi, S.O.; et al. Association Between Inherited Germline Mutations in Cancer Predisposition Genes and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer. JAMA 2018, 319, 2401–2409.

- Gentiluomo, M.; Canzian, F.; Nicolini, A.; Gemignani, F.; Landi, S.; Campa, D. Germline genetic variability in pancreatic cancer risk and prognosis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 79, 105–131.

- Zhang, Y.D.; Hurson, A.N.; Zhang, H.; Choudhury, P.P.; Easton, D.F.; Milne, R.L.; Simard, J.; Hall, P.; Michailidou, K.; Dennis, J.; et al. Assessment of polygenic architecture and risk prediction based on common variants across fourteen cancers. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3353.

- Wang, X.Y.; Chen, H.T.; Na, R.; Jiang, D.K.; Lin, X.L.; Yang, F.; Jin, C.; Fu, D.L.; Xu, J.F. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms based genetic risk score in the prediction of pancreatic cancer risk. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 3076–3086.

- Kim, J.; Yuan, C.; Babic, A.; Bao, Y.; Clish, C.B.; Pollak, M.N.; Amundadottir, L.T.; Klein, A.P.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R.Z.; Pandharipande, P.V.; et al. Genetic and Circulating Biomarker Data Improve Risk Prediction for Pancreatic Cancer in the General Population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 999–1008.

- Galeotti, A.A.; Gentiluomo, M.; Rizzato, C.; Obazee, O.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Pasquali, C.; Nentwich, M.; Cavestro, G.M.; Pezzilli, R.; Greenhalf, W.; et al. Polygenic and multifactorial scores for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma risk prediction. J. Med. Genet. 2021, 58, 369–377.

- Deer, E.L.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, J.; Coursen, J.D.; Shea, J.E.; Ngatia, J.; Scaife, C.L.; Firpo, M.A.; Mulvihill, S.J. Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas 2010, 39, 425–435.

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Brody, J.R.; Gallmeier, E.; Cunningham, S.C.; Dezentje, D.A.; Shen, D.; Hruban, R.H.; Kern, S.E. Functional defects in the fanconi anemia pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 651–657.

- Hingorani, S.R.; Petricoin, E.F.; Maitra, A.; Rajapakse, V.; King, C.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Ross, S.; Conrads, T.P.; Veenstra, T.D.; Hitt, B.A.; et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 437–450.

- Olive, K.P.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Davidson, C.J.; Gopinathan, A.; McIntyre, D.; Honess, D.; Madhu, B.; Goldgraben, M.A.; Caldwell, M.E.; Allard, D.; et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 2009, 324, 1457–1461.

- Guerra, C.; Barbacid, M. Genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 2013, 7, 232–247.

- Skoulidis, F.; Cassidy, L.D.; Pisupati, V.; Jonasson, J.G.; Bjarnason, H.; Eyfjord, J.E.; Karreth, F.A.; Lim, M.; Barber, L.M.; Clatworthy, S.A.; et al. Germline Brca2 heterozygosity promotes Kras(G12D) -driven carcinogenesis in a murine model of familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 499–509.

- Drosos, Y.; Escobar, D.; Chiang, M.Y.; Roys, K.; Valentine, V.; Valentine, M.B.; Rehg, J.E.; Sahai, V.; Begley, L.A.; Ye, J.; et al. ATM-deficiency increases genomic instability and metastatic potential in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11144.

- Hwang, C.I.; Boj, S.F.; Clevers, H.; Tuveson, D.A. Preclinical models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Pathol. 2016, 238, 197–204.

- Boj, S.F.; Hwang, C.I.; Baker, L.A.; Chio, I.I.C.; Engle, D.D.; Corbo, V.; Jager, M.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Tiriac, H.; Spector, M.S.; et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell 2015, 160, 324–338.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

513

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 Aug 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No