Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sunil Sukumaran | -- | 2800 | 2022-08-08 18:50:13 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -26 word(s) | 2774 | 2022-08-09 04:07:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Sukumaran, S.K.; Palayyan, S.R. Sweet Taste Signaling. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25966 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Sukumaran SK, Palayyan SR. Sweet Taste Signaling. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25966. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Sukumaran, Sunil Kumar, Salin Raj Palayyan. "Sweet Taste Signaling" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25966 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Sukumaran, S.K., & Palayyan, S.R. (2022, August 08). Sweet Taste Signaling. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25966

Sukumaran, Sunil Kumar and Salin Raj Palayyan. "Sweet Taste Signaling." Encyclopedia. Web. 08 August, 2022.

Copy Citation

Sweet taste, a proxy for sugar-derived calories, is an important driver of food intake, and animals have evolved robust molecular and cellular machinery for sweet taste signaling. The below is a description of the mechanisms underlying sweet taste signaling in the periphery, and the factors regulating them.

sweet taste receptor

gustation

G-protein-coupled receptor

1. Introduction

It is thought that the taste system evolved to rapidly evaluate whether a potential food is suitable for consumption. Generally, five primary taste qualities are thought to exist: sweet, bitter, salty, sour, and umami ([1][2][3] and references therein). Although this classification captures all perceptually unique taste qualities, it does not include important classes of macronutrients such as fats, and minerals such as iron and calcium. It is now well recognized that the latter set of nutrients and others such as water do activate the taste system, although whether these findings warrant considering them as core taste qualities is still debated [2][3][4].

Carbohydrates are one of the fundamental building blocks of life, besides constituting a readily metabolizable source of energy. Although carbohydrate-sensing mechanisms, tuned primarily to their mono and disaccharide forms, are found in all kingdoms of life, their incorporation into the taste system evolved independently in both invertebrates such as insects and crustaceans and vertebrates ([4][5] and references therein). Sweet taste is perhaps the taste quality with the highest appetitive valence, and the innate preference for sweet-tasting foods arises very early in mammalian development [3]. Sweet taste presents one of the most interesting cases of plant–animal coevolution [6][7]. Plants pack their fruits with carbohydrates and sugars to provide a source of energy for the germinating seed. Animals, on the other hand, seek out fruits, as they are a rich source of sugar-derived calories and other nutrients such as vitamins and minerals. Although the destruction of the seeds by animals could be detrimental to plants, they also represent an opportunity for their dispersal. Thus, plants adapted by making hard-shelled seeds housed inside fleshy fruits that have a better chance of surviving the animal digestive system. This arrangement serves both parties well, and has unforeseen consequences as well; e.g., fruit-eating monkeys are thought to be evolutionarily more successful because they help in seed dispersal, ensuring a more stable food supply during lean times. However, the strong preference for sugars has turned to the detriment because most humans now live in an environment with far greater access to energy-rich foods, which is very different from that of our ancestors. With the spread of industrialization and colonialization, sugar plantations sprung up in many tropical colonies over the past 200 years, making this once luxury item extremely cheap and accessible [8]. More recently, high-fructose corn syrup made from starch has become a popular sugar source, especially in countries that cultivate a large amount of corn such as the USA, where it accounts for up to one-third of the caloric sugars used in processed foods [9]. Sugars such as sucrose and fructose and even glucose are not essential nutrients, unlike some amino acids and fats. However, the food industry was quick to latch on to the sweet tooth, and most processed and ultra-processed foods have unhealthily high levels of added sugars (and fats and salt), while simultaneously being low in beneficial but bitter-tasting phytonutrients and dietary fiber. This profoundly unhealthy diet has fueled a worldwide increase in conditions such as obesity and diabetes, placing an immense strain on the public health system and the wider economy ([10][11] and references therein). Noncaloric sweeteners (NCSs), compounds that taste sweet but have no caloric value, were among the first synthetic food additives to be approved [12][13]. However, the health benefits of existing NCSs are doubtful, and their consumer acceptance has still not attained full potential due to their off taste. In addition, they have been implicated in metabolic dysregulation, likely due to their post-ingestive signaling and adverse effects on intestinal microbiota [14][15]. In addition, strategies such as progressively reducing the sugar content of foods can reduce the taste threshold but not the pleasantness of sugars, although the underlying molecular mechanism(s) is/are not known [16].

2. Organization of the Taste System

The taste system is exquisitely organized to sense and transduce taste signals to the brain. In mammals such as mice and humans, most taste papillae are distributed on the surface of the tongue, and isolated clusters are found on the soft palate and larynx as well [1][3][4]. Among them, the fungiform papillae (FFP), located on the anterior tongue each house a single taste bud, and the circumvallate (CVP) and foliate papillae (FOP), located medially and laterally on the back of the tongue, respectively, each contain clusters of multiple taste buds. Each taste bud is made up of 50–100 taste cells subdivided into at least four subtypes based on morphology (types I–IV) and at least five based on the taste quality they transduce signals of [1][17][18]. Type I cells are the most numerous, but they are the least well studied among taste cells. They are functionally analogous to glia in the nervous system and may transduce amiloride-sensitive salty taste. The type II cells consist of function subtypes that express G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) for sweet, umami, or bitter tastants and their downstream signaling components [1][19]. They do not form typical synapses with taste nerves, but they secrete the neurotransmitter adenosine triphosphate (ATP) that binds to the purinergic receptors P2X2 and P2X3 in adjacent taste nerves [20]. The type III cells are analogous to neurons in that they form true synapses with taste nerves and secrete classical neurotransmitters such as 5-hydroxy-tryptamine and gamma amino butyric acid. They also generate true action potentials and possess voltage-gated calcium channels that trigger neurotransmitter release upon stimulation [21][22][23][24][25]. They include the functional subtypes that express receptors for sour and/or the amiloride-insensitive salty taste qualities [26]. Mature taste cells have half-lives ranging from 3 to 24 days and are continually regenerated from stem cells located at the base of taste buds [27]. Type IV cells are thought to be post-mitotic precursors of mature taste cells at an intermediate stage of differentiation [17][28][29]. Taste buds in the FFP are innervated by the chorda tympani branch of the facial (seventh cranial) nerve, and those in the CVP and FOP are innervated by the glossopharyngeal (ninth cranial) nerve that, together, transmit taste signals to the gustatory cortex through a multistep neuronal relay [1][4].

3. Pathways Mediating Sweet Taste Signaling

3.1. Sweet Taste Stimuli Are Structurally Diverse

Although sugars such as sucrose and fructose are the most well-known class of sweet taste stimuli, a large set of structurally unrelated molecules can elicit sweet taste, most of which are NCSs [13][30][31]. These include both small molecules and proteins derived from fruits and/or leaves of several tropical plants and synthetic chemicals, most of which are several hundreds to thousands-fold sweeter than sucrose on a molar basis [13][31]. The ecological significance of plant-derived NCSs is not known. It has been suggested that they represent a case of molecular mimicry that allows plants to substitute sugars for metabolically less costly molecules [32]. However, it is possible that some of them, such as steviol glycosides, may have other functions, such as acting as precursors for plant hormones, osmolytes, or feeding deterrents, and their sweetness might in fact be accidental [33]. In addition to the above agonists, a few sweet taste antagonists such as gymnemic acids, gurmarin, and lactisole are also known [34][35]. The mystery of how such a diverse set of molecules can elicit sweet taste was only solved after the discovery of the molecular mechanisms of sweet taste signaling, as described below.

3.2. The G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Pathway for Sweet Taste Signaling

3.2.1. The Primary Sweet Taste Receptor Is a Heterodimer of Taste 1 Receptor Members 2 and 3 (TAS1R2 + TAS1R3)

Rodents are the preferred model system for molecular studies of taste transduction, due to the rarity of taste cells in the tongue (~1% of all cells in the lingual epithelium) and the consequent difficulty obtaining them from humans. Until the 2000s, it was believed that sweet taste is transduced by multiple receptors. The discovery of the expression of the G-protein alpha subunit Gnat3 (G-protein subunit alpha transducin 3, aka gustducin) and the subsequent demonstration that Gnat3 knockout mice have diminished sweet taste responses strongly suggested that GPCRs mediate sweet taste signaling [36][37]. Genetic studies in mice using sucrose-preferring strains such as C57BL/6 showed strong association of this trait with the Sac locus in chromosome 4, which was later shown to encode the GPCR Tas1r3 (taste 1 receptor member 3) [38][39][40]. Further molecular studies identified the Tas1r2 subunit of the receptor belonging to the same gene family [38]. Heterologous expression studies confirmed that the sweet taste receptor (STR) is a heterodimer of the two subunits (TAS1R2 + TAS1R3) [38][41]. TAS1R2 by itself is incapable of signal transduction; however, a homodimer of TAS1R3 may transduce sweet taste signals from natural sugars such as high concentrations of sucrose [42]. TAS1Rs belong to the class C subfamily of GPCRs that also includes the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGlurs), vomeronasal receptors type 2 (V2rs), and the calcium-sensing receptor [43]. Like other members of the family, T1R2 and T1R3 possess at their amino terminus a Venus flytrap domain (VFT) composed of two lobes separated by a large cleft, followed by a short cysteine-rich domain (CRD), a seven transmembrane (7TM) domain, and a short intracellular domain at its carboxy terminus [41][44]. The TAS1R family consists of one other member, TAS1R1 that heterodimerizes with TAS1R3 to form the umami taste receptor. Using systematic mutagenesis studies of heterologously expressed STR, it was shown that it is capable of binding to all known sweet tastants and inhibitors [41][45][46]. These studies also helped identify the locations of the binding sites for the ligands distributed among the VFT, CTD, and 7TM domains of the T1R2 and T1R3 subunits [41][44][45][46]. Collectively, these studies demonstrated how the STR acts as a receptor for all known classes of sweeteners.

3.2.2. STR-Mediated Signal Transduction Pathways

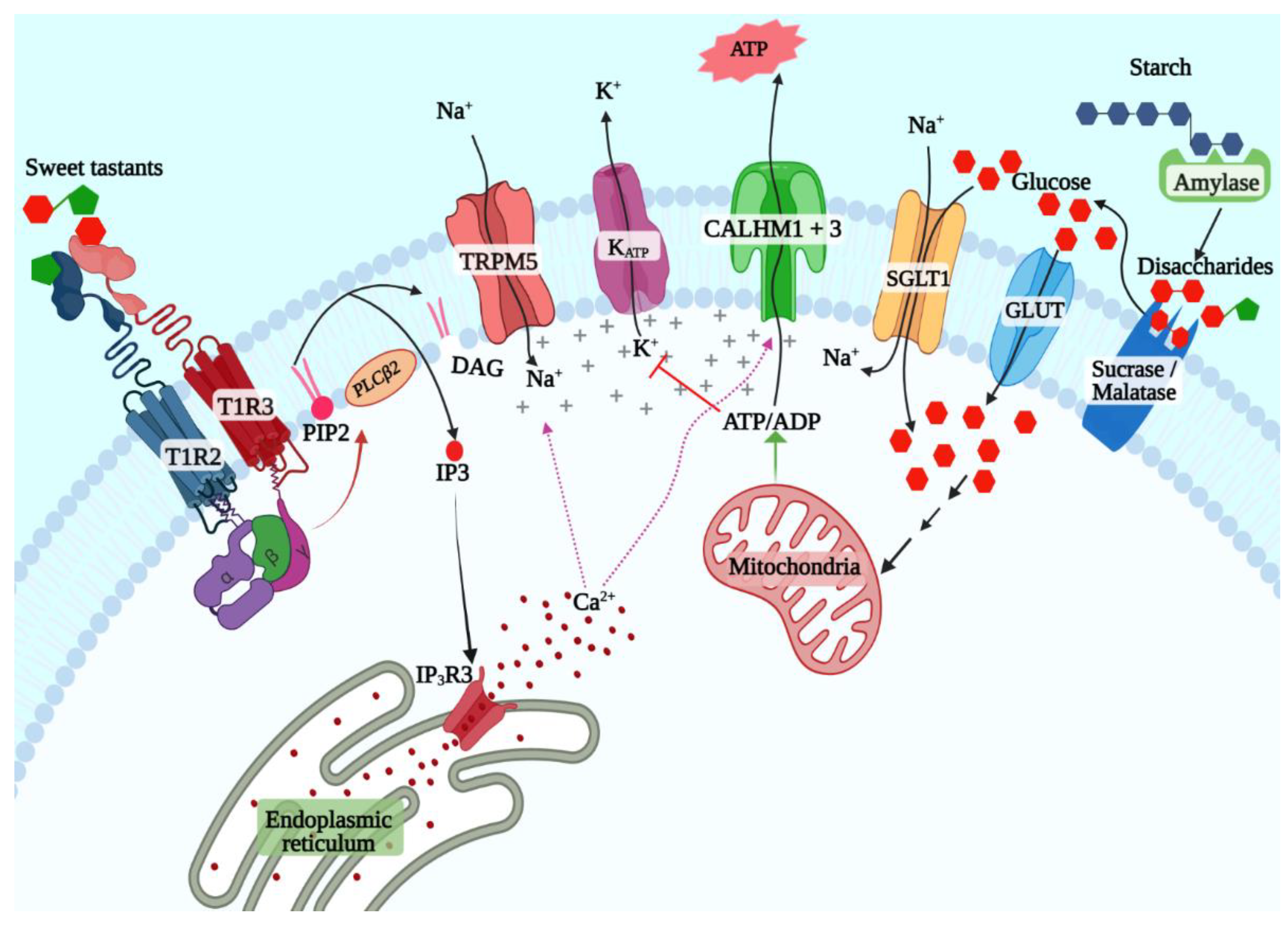

Early studies from the 1970s onwards implicated cyclic adenosine (cAMP) as the key second messenger for sweet taste signaling [47]. The expression of adenyl cyclases and phosphodiesterases and sweetener-evoked cAMP generation in taste buds was demonstrated in taste cells from multiple species [48][49][50]. However, more recent studies have shown that the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) pathway is the primary pathway downstream of the STR (Figure 1) [1][51]. The cAMP pathway might play a regulatory role or be more relevant for signaling evoked by a subset of ligands such as caloric sugars. Ligand binding to the STR leads to the exchange of guanosine-5′-triphosphate (GTP) for GDP by the Gα subunit, leading to its dissociation from the Gβγ subunit [52]. The latter activates phospholipase C β2 (PLCβ2), which cleaves phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to diacyl glycerol and IP3 [51]. IP3 binds to its receptor (ITPR3) expressed on the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum, inducing the release of Ca2+ [53]. The subsequent elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels cause opening of the monovalent cation-selective channel transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 5 (TRPM5), which leads to sodium influx and membrane depolarization [54][55]. Depolarization triggers the release of the neurotransmitter adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through a heterodimeric channel formed by the calcium homeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1) and CALHM3 subunits, which activates the purinergic receptors in the taste nerves, leading to transmission of taste information to the brain [56][57].

Figure 1. T1R2 + T1R3-dependent and -independent sweet taste signaling pathways.

3.2.3. STR-Independent Sweet Taste Signaling Pathways

Numerous studies since the discovery of the STR have affirmed its primacy in sweet taste signaling. However, behavioral and taste nerve recording experiments showed that Tas1r3 knockout mice retain responses to caloric sugars, while their responses to NCSs are almost completely abolished [58]. This was also observed in another study using Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 knockout mice, although Tas1r2 + Tas1r3 double-knockout mice did not show responses to sugars [59]. Similar results were also observed in knockout mice lacking Gnat3 and Trpm5 as well [37][60][61][62]. Since TAS1R2 by itself is incapable of responding to sweeteners, it raised the possibility that STR-independent caloric sugar-specific taste signaling pathways exist in taste cells [41]. Two such pathways have been well studied in other tissues: the ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP)-dependent pathway first identified in pancreatic beta cells and the sodium–glucose cotransporter (SGLT) family mediated pathway first identified in the enteroendocrine cells in the small and large intestine. The latter is the simpler of the two; SGLT1 cotransports sodium ions and glucose (or galactose) from the intestinal lumen in a 2:1 ratio, leading to depolarization and action potential generation and secretion of the peptide hormones such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) and GLP2 from enteroendocrine cells [63]. The KATP pathway depends on the generation of ATP from glucose transported into the beta cells. Several features of this pathway ensure that it serves a sensory role in the beta cells. Beta cells express the low-affinity facilitative glucose transporter GLUT2 and the low-affinity hexokinase glucokinase, both of which are active only at physiologically high glucose concentrations (above 5.5 mmol/L) that occur after a meal in nondiabetic individuals [64][65][66]. Phosphorylated glucose is metabolized through glycolysis and citric acid cycle, thus elevating the [ATP]/[ADP] ratio, leading to the closure of the KATP channel, depolarization of the cell membrane, and secretion of insulin. Since then, the KATP pathway was shown to be a potent glucose sensor in several other cell types, including the pancreatic alpha and delta cells, enteroendocrine cells, and glucose-sensing neurons in the hypothalamus as well, where it mediates a variety of responses such as gut hormone or neurotransmitter secretion depending on the cell type in question.

Several lines of evidence indicate that both these pathways are active in sweet taste cells [67][68][69][70][71]. A copious amount of amylase is secreted by salivary glands, enabling the production of maltose from starch in the oral cavity [72][73]. Similarly, the disaccharidases maltase-glucoamylase (MGAM, aka maltase) and sucrase-isomaltase (SI, aka sucrase), first identified in the brush border of enterocytes, are also expressed in taste cells and may generate glucose and fructose from maltose and sucrose in the vicinity of taste cells (Figure 1) [67]. Glucose transporters, including SGLT1 and several members of the GLUT family and the KATP channel, are coexpressed with Tas1r3 in sweet taste cells (Figure 1) [69][71]. Behavioral and single-fiber taste nerve recording studies in mice showed that sweet taste responses are enhanced by additions of low concentration (10 mM) of sodium chloride, and this could be inhibited by the addition of phlorizin, an inhibitor of SGLT1 but not of GLUT family transporters [68]. These results were also confirmed in humans using psychophysical studies [74]. Similarly, KATP-mediated currents were demonstrated in murine taste cells, and the taste nerve responses to caloric sugars in Tas1r3 knockout mice were abolished by applying voglibose, an inhibitor of maltase and sucrase confirming the presence of the caloric sugar pathway in sweet taste signaling [67][69].

3.3. Physiological and Behavioral Significance of Sweet Taste Signaling through Multiple Pathways

The STR-independent and -dependent pathways have overlapping but distinct functional properties. As mentioned above, the STR is sensitive to both sugars and NCSs, while the SGLT1 and KATP pathways are tuned exclusively to caloric sugars. The sensitivity, kinetics of activation, and adaptation of these pathways are different. The STR has comparatively low sensitivity to caloric sugars such as sucrose and glucose (Km of 62 mM for sucrose, and above 100 mM for glucose) [75][76]. However, the Km of SGLT1 for glucose is 1.5 mM, and that of GLUT2 is >6 mM, enabling them to sense sugars at much lower concentrations than the STR [65]. Thus, it is possible that they are more relevant to sensing the low concentrations of monosaccharides generated from starch in the mouth during mastication [72]. The STR is subject to faster adaptation by endocytosis, as discussed below, while the membrane localization of SGLT and GLUT family members is increased in the plasma membrane (PM) upon glucose stimulation [77][78]. Interestingly, in the enterocytes, mRNA and protein levels and PM localization of SGLT1 are augmented by STR signaling in the neighboring enteroendocrine cells [79]. The STR pathway mediates the behavioral attraction to sugars, while the behavioral output of the KATP pathway is still under investigation. Sodium–glucose cotransport by SGLT1 may explain the enhancement of sweet taste by low concentrations of salt [69]. Interestingly, the KATP pathway was shown to mediate cephalic-phase insulin responses (CPIR) in mice [80][81]. In humans, oral carbohydrate, but not NCS, stimulation caused an increase in motor output in subjects undertaking fatigue-inducing exercise [82]. The above findings indicate that sugars and NCSs may activate at least partially nonoverlapping neural pathways and, consequently, may mediate different behavioral and physiological responses. The STR is also expressed in nutrient-sensing tissues throughout the body, such as the enteroendocrine cells, pancreas, and hypothalamus, where it is involved in regulation of incretin and insulin secretion and in regulating energy balance and food intake. These extraoral roles of the STR, coupled with its roles in taste and CPIR induction, might be the reason why sweet taste signaling is linked to metabolic conditions. Interestingly, high-carbohydrate or fat-fed Tas1r3 knockout mice are resistant to development of obesity and hyperinsulinemia [83][84].

References

- Liman, E.R.; Zhang, Y.V.; Montell, C. Peripheral coding of taste. Neuron 2014, 81, 984–1000.

- Chaudhari, N.; Roper, S.D. The cell biology of taste. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 285–296.

- Beauchamp, G.K. Why do we like sweet taste: A bitter tale? Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164 Pt B, 432–437.

- Yarmolinsky, D.A.; Zuker, C.S.; Ryba, N.J.P. Common sense about taste: From mammals to insects. Cell 2009, 139, 234–244.

- Derby, C.D.; Kozma, M.T.; Senatore, A.; Schmidt, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Reception and Perireception in Crustacean Chemoreception: A Comparative Review. Chem. Senses 2016, 41, 381–398.

- Jordano, P.; Forget, P.M.; Lambert, J.E.; Bohning-Gaese, K.; Traveset, A.; Wright, S.J. Frugivores and seed dispersal: Mechanisms and consequences for biodiversity of a key ecological interaction. Biol. Lett. 2011, 7, 321–323.

- Sussman, R.W. Primate origins and the evolution of angiosperms. Am. J. Primatol. 1991, 23, 209–223.

- Abbott, E. Sugar: A Bittersweet History; Penguin: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008; 453p.

- Febbraio, M.A.; Karin, M. “Sweet death”: Fructose as a metabolic toxin that targets the gut-liver axis. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2316–2328.

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814.

- Mozaffarian, D.; Hao, T.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2392–2404.

- Hu, F.B. Resolved: There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 606–619.

- Mooradian, A.D.; Smith, M.; Tokuda, M. The role of artificial and natural sweeteners in reducing the consumption of table sugar: A narrative review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 18, 1–8.

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Thaiss, C.A.; Maza, O.; Israeli, D.; Zmora, N.; Gilad, S.; Weinberger, A.; et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 2014, 514, 181–186.

- Davidson, T.L.; Martin, A.A.; Clark, K.; Swithers, S.E. Intake of high-intensity sweeteners alters the ability of sweet taste to signal caloric consequences: Implications for the learned control of energy and body weight regulation. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2011, 64, 1430–1441.

- Wise, P.M.; Nattress, L.; Flammer, L.J.; Beauchamp, G.K. Reduced dietary intake of simple sugars alters perceived sweet taste intensity but not perceived pleasantness. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 50–60.

- Kapsimali, M.; Barlow, L.A. Developing a sense of taste. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013, 24, 200–209.

- Barlow, L.A. Progress and renewal in gustation: New insights into taste bud development. Development 2015, 142, 3620–3629.

- Kinnamon, S.C.; Finger, T.E. Recent advances in taste transduction and signaling. F1000Research 2019, 8, 2117.

- Kinnamon, S.C.; Finger, T.E. A taste for ATP: Neurotransmission in taste buds. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 264.

- Dando, R.; Roper, S.D. Acetylcholine is released from taste cells, enhancing taste signalling. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 3009–3017.

- Huang, Y.A.; Pereira, E.; Roper, S.D. Acid stimulation (sour taste) elicits GABA and serotonin release from mouse taste cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25471.

- Roper, S.D. Chemical and electrical synaptic interactions among taste bud cells. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 20, 118–125.

- Huang, Y.A.; Stone, L.M.; Pereira, E.; Yang, R.; Kinnamon, J.C.; Dvoryanchikov, G.; Chaudhari, N.; Finger, T.E.; Kinnamon, S.C.; Roper, S.D. Knocking out P2X receptors reduces transmitter secretion in taste buds. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 13654–13661.

- Huang, Y.J.; Maruyama, Y.; Lu, K.S.; Pereira, E.; Plonsky, I.; Baur, J.E.; Wu, D.; Roper, S.D. Mouse taste buds use serotonin as a neurotransmitter. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 843–847.

- Lewandowski, B.C.; Sukumaran, S.K.; Margolskee, R.F.; Bachmanov, A.A. Amiloride-Insensitive Salt Taste Is Mediated by Two Populations of Type III Taste Cells with Distinct Transduction Mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 1942–1953.

- Perea-Martinez, I.; Nagai, T.; Chaudhari, N. Functional Cell Types in Taste Buds Have Distinct Longevities. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53399.

- Barlow, L.A.; Klein, O.D. Developing and regenerating a sense of taste. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2015, 111, 401–419.

- Miura, H.; Scott, J.K.; Harada, S.; Barlow, L.A. Sonic hedgehog-Expressing Basal Cells Are General Post-Mitotic Precursors of Functional Taste Receptor Cells. Dev. Dyn. 2014, 243, 1286–1297.

- Ahmed, J.; Preissner, S.; Dunkel, M.; Worth, C.L.; Eckert, A.; Preissner, R. SuperSweet—A resource on natural and artificial sweetening agents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D377–D382.

- Picone, D.; Temussi, P.A. Dissimilar sweet proteins from plants: Oddities or normal components? Plant Sci. 2012, 195, 135–142.

- Wintjens, R.; Viet, T.M.; Mbosso, E.; Huet, J. Hypothesis/review: The structural basis of sweetness perception of sweet-tasting plant proteins can be deduced from sequence analysis. Plant Sci. 2011, 181, 347–354.

- Ceunen, S.; Geuns, J.M. Steviol glycosides: Chemical diversity, metabolism, and function. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1201–1228.

- Jiang, P.; Cui, M.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Z.; Snyder, L.A.; Benard, L.M.; Osman, R.; Margolskee, R.F.; Max, M. Lactisole interacts with the transmembrane domains of human T1R3 to inhibit sweet taste. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 15238–15246.

- Pothuraju, R.; Sharma, R.K.; Chagalamarri, J.; Jangra, S.; Kumar Kavadi, P. A systematic review of Gymnema sylvestre in obesity and diabetes management. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 834–840.

- McLaughlin, S.K.; McKinnon, P.J.; Margolskee, R.F. Gustducin is a taste-cell-specific G protein closely related to the transducins. Nature 1992, 357, 563–569.

- Wong, G.T.; Gannon, K.S.; Margolskee, R.F. Transduction of bitter and sweet taste by gustducin. Nature 1996, 381, 796–800.

- Nelson, G.; Hoon, M.A.; Chandrashekar, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ryba, N.J.; Zuker, C.S. Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell 2001, 106, 381–390.

- Max, M.; Shanker, Y.G.; Huang, L.; Rong, M.; Liu, Z.; Campagne, F.; Weinstein, H.; Damak, S.; Margolskee, R.F. Tas1r3, encoding a new candidate taste receptor, is allelic to the sweet responsiveness locus Sac. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 58–63.

- Montmayeur, J.P.; Liberles, S.D.; Matsunami, H.; Buck, L.B. A candidate taste receptor gene near a sweet taste locus. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 492–498.

- Cui, M.; Jiang, P.; Maillet, E.; Max, M.; Margolskee, R.F.; Osman, R. The heterodimeric sweet taste receptor has multiple potential ligand binding sites. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 4591–4600.

- Kurihara, Y. Characteristics of antisweet substances, sweet proteins, and sweetness-inducing proteins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1992, 32, 231–252.

- Ellaithy, A.; Gonzalez-Maeso, J.; Logothetis, D.A.; Levitz, J. Structural and Biophysical Mechanisms of Class C G Protein-Coupled Receptor Function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 1049–1064.

- DuBois, G.E. Molecular mechanism of sweetness sensation. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164 Pt B, 453–463.

- Jiang, P.; Cui, M.; Zhao, B.; Snyder, L.A.; Benard, L.M.; Osman, R.; Max, M.; Margolskee, R.F. Identification of the cyclamate interaction site within the transmembrane domain of the human sweet taste receptor subunit T1R3. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 34296–34305.

- Jiang, P.; Ji, Q.; Liu, Z.; Snyder, L.A.; Benard, L.M.; Margolskee, R.F.; Max, M. The cysteine-rich region of T1R3 determines responses to intensely sweet proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 45068–45075.

- Kurihara, K.; Koyama, N. High activity of adenyl cyclase in olfactory and gustatory organs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1972, 48, 30–34.

- Abaffy, T.; Trubey, K.R.; Chaudhari, N. Adenylyl cyclase expression and modulation of cAMP in rat taste cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2003, 284, C1420–C1428.

- Avenet, P.; Lindemann, B. Patch-clamp study of isolated taste receptor cells of the frog. J. Membr. Biol. 1987, 97, 223–240.

- Striem, B.J.; Pace, U.; Zehavi, U.; Naim, M.; Lancet, D. Sweet tastants stimulate adenylate cyclase coupled to GTP-binding protein in rat tongue membranes. Biochem. J. 1989, 260, 121–126.

- Zhang, Y.; Hoon, M.A.; Chandrashekar, J.; Mueller, K.L.; Cook, B.; Wu, D.; Zuker, C.S.; Ryba, N.J. Coding of sweet, bitter, and umami tastes: Different receptor cells sharing similar signaling pathways. Cell 2003, 112, 293–301.

- Huang, L.; Shanker, Y.G.; Dubauskaite, J.; Zheng, J.Z.; Yan, W.; Rosenzweig, S.; Spielman, A.I.; Max, M.; Margolskee, R.F. Ggamma13 colocalizes with gustducin in taste receptor cells and mediates IP3 responses to bitter denatonium. Nat. Neurosci. 1999, 2, 1055–1062.

- Clapp, T.R.; Stone, L.M.; Margolskee, R.F.; Kinnamon, S.C. Immunocytochemical evidence for co-expression of Type III IP3 receptor with signaling components of bitter taste transduction. BMC Neurosci. 2001, 2, 6.

- Perez, C.A.; Huang, L.; Rong, M.; Kozak, J.A.; Preuss, A.K.; Zhang, H.; Max, M.; Margolskee, R.F. A transient receptor potential channel expressed in taste receptor cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 1169–1176.

- Liu, D.; Liman, E.R. Intracellular Ca2+ and the phospholipid PIP2 regulate the taste transduction ion channel TRPM5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15160–15165.

- Taruno, A.; Vingtdeux, V.; Ohmoto, M.; Ma, Z.; Dvoryanchikov, G.; Li, A.; Adrien, L.; Zhao, H.; Leung, S.; Abernethy, M.; et al. CALHM1 ion channel mediates purinergic neurotransmission of sweet, bitter and umami tastes. Nature 2013, 495, 223–226.

- Ma, Z.; Taruno, A.; Ohmoto, M.; Jyotaki, M.; Lim, J.C.; Miyazaki, H.; Niisato, N.; Marunaka, Y.; Lee, R.J.; Hoff, H.; et al. CALHM3 Is Essential for Rapid Ion Channel-Mediated Purinergic Neurotransmission of GPCR-Mediated Tastes. Neuron 2018, 98, 547–561.e10.

- Damak, S.; Rong, M.; Yasumatsu, K.; Kokrashvili, Z.; Varadarajan, V.; Zou, S.; Jiang, P.; Ninomiya, Y.; Margolskee, R.F. Detection of sweet and umami taste in the absence of taste receptor T1r3. Science 2003, 301, 850–853.

- Zhao, G.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hoon, M.A.; Chandrashekar, J.; Erlenbach, I.; Ryba, N.J.; Zuker, C.S. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell 2003, 115, 255–266.

- Damak, S.; Rong, M.; Yasumatsu, K.; Kokrashvili, Z.; Perez, C.A.; Shigemura, N.; Yoshida, R.; Mosinger, B., Jr.; Glendinning, J.I.; Ninomiya, Y.; et al. Trpm5 null mice respond to bitter, sweet, and umami compounds. Chem. Senses 2006, 31, 253–264.

- Eddy, M.C.; Eschle, B.K.; Peterson, D.; Lauras, N.; Margolskee, R.F.; Delay, E.R. A conditioned aversion study of sucrose and SC45647 taste in TRPM5 knockout mice. Chem. Senses 2012, 37, 391–401.

- Ohkuri, T.; Yasumatsu, K.; Horio, N.; Jyotaki, M.; Margolskee, R.F.; Ninomiya, Y. Multiple sweet receptors and transduction pathways revealed in knockout mice by temperature dependence and gurmarin sensitivity. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr] Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R960–R971.

- Armour, S.L.; Frueh, A.; Knudsen, J.G. Sodium, Glucose and Dysregulated Glucagon Secretion: The Potential of Sodium Glucose Transporters. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 837664.

- Hjorne, A.P.; Modvig, I.M.; Holst, J.J. The Sensory Mechanisms of Nutrient-Induced GLP-1 Secretion. Metabolites 2022, 12, 420.

- Ishihara, H. Metabolism-secretion coupling in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetol. Int. 2022, 13, 463–470.

- Thompson, B.; Satin, L.S. Beta-Cell Ion Channels and Their Role in Regulating Insulin Secretion. Compr. Physiol. 2021, 11, 1–21.

- Sukumaran, S.K.; Yee, K.K.; Iwata, S.; Kotha, R.; Quezada-Calvillo, R.; Nichols, B.L.; Mohan, S.; Pinto, B.M.; Shigemura, N.; Ninomiya, Y.; et al. Taste cell-expressed alpha-glucosidase enzymes contribute to gustatory responses to disaccharides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 6035–6040.

- Yasumatsu, K.; Ohkuri, T.; Yoshida, R.; Iwata, S.; Margolskee, R.F.; Ninomiya, Y. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 as a sugar taste sensor in mouse tongue. Acta Physiol. 2020, 230, e13529.

- Yee, K.K.; Sukumaran, S.K.; Kotha, R.; Gilbertson, T.A.; Margolskee, R.F. Glucose transporters and ATP-gated K+ (KATP) metabolic sensors are present in type 1 taste receptor 3 (T1r3)-expressing taste cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5431–5436.

- Toyono, T.; Seta, Y.; Kataoka, S.; Oda, M.; Toyoshima, K. Differential expression of the glucose transporters in mouse gustatory papillae. Cell Tissue Res. 2011, 345, 243–252.

- Merigo, F.; Benati, D.; Cristofoletti, M.; Osculati, F.; Sbarbati, A. Glucose transporters are expressed in taste receptor cells. J. Anat. 2011, 219, 243–252.

- Mandel, A.L.; Peyrot des Gachons, C.; Plank, K.L.; Alarcon, S.; Breslin, P.A. Individual differences in AMY1 gene copy number, salivary alpha-amylase levels, and the perception of oral starch. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13352.

- Mandel, A.L.; Breslin, P.A. High endogenous salivary amylase activity is associated with improved glycemic homeostasis following starch ingestion in adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 853–858.

- Breslin, P.A.S.; Izumi, A.; Tharp, A.; Ohkuri, T.; Yokoo, Y.; Flammer, L.J.; Rawson, N.E.; Margolskee, R.F. Evidence that human oral glucose detection involves a sweet taste pathway and a glucose transporter pathway. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256989.

- Zhang, F.; Klebansky, B.; Fine, R.M.; Liu, H.; Xu, H.; Servant, G.; Zoller, M.; Tachdjian, C.; Li, X. Molecular mechanism of the sweet taste enhancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4752–4757.

- Servant, G.; Tachdjian, C.; Tang, X.Q.; Werner, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Kamdar, P.; Petrovic, G.; Ditschun, T.; Java, A.; et al. Positive allosteric modulators of the human sweet taste receptor enhance sweet taste. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4746–4751.

- Beloto-Silva, O.; Machado, U.F.; Oliveira-Souza, M. Glucose-induced regulation of NHEs activity and SGLTs expression involves the PKA signaling pathway. J. Membr. Biol. 2011, 239, 157–165.

- Yuan, Y.; Kong, F.; Xu, H.; Zhu, A.; Yan, N.; Yan, C. Cryo-EM structure of human glucose transporter GLUT4. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2671.

- Margolskee, R.F.; Dyer, J.; Kokrashvili, Z.; Salmon, K.S.; Ilegems, E.; Daly, K.; Maillet, E.L.; Ninomiya, Y.; Mosinger, B.; Shirazi-Beechey, S.P. T1R3 and gustducin in gut sense sugars to regulate expression of Na+-glucose cotransporter 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15075–15080.

- Glendinning, J.I.; Lubitz, G.S.; Shelling, S. Taste of glucose elicits cephalic-phase insulin release in mice. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 192, 200–205.

- Glendinning, J.I.; Frim, Y.G.; Hochman, A.; Lubitz, G.S.; Basile, A.J.; Sclafani, A. Glucose elicits cephalic-phase insulin release in mice by activating KATP channels in taste cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2017, 312, R597–R610.

- Gant, N.; Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D. Carbohydrate in the mouth immediately facilitates motor output. Brain Res. 2010, 1350, 151–158.

- Glendinning, J.I.; Gillman, J.; Zamer, H.; Margolskee, R.F.; Sclafani, A. The role of T1r3 and Trpm5 in carbohydrate-induced obesity in mice. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 50–58.

- Murovets, V.O.; Bachmanov, A.A.; Travnikov, S.V.; Churikova, A.A.; Zolotarev, V.A. The Involvement of the T1R3 Receptor Protein in the Control of Glucose Metabolism in Mice at Different Levels of Glycemia. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 50, 334–344.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.6K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 Aug 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No