Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yongquan Tang | -- | 1382 | 2022-07-23 08:57:12 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1382 | 2022-07-25 02:59:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Tang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Qin, S.; Zhou, L.; Gao, W.; Shen, Z. Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25457 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Tang Y, Zhang Z, Chen Y, Qin S, Zhou L, Gao W, et al. Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25457. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Tang, Yongquan, Zhe Zhang, Yan Chen, Siyuan Qin, Li Zhou, Wei Gao, Zhisen Shen. "Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25457 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Tang, Y., Zhang, Z., Chen, Y., Qin, S., Zhou, L., Gao, W., & Shen, Z. (2022, July 23). Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25457

Tang, Yongquan, et al. "Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

Undue elevation of ROS levels commonly occurs during cancer evolution as a result of various antitumor therapeutics and/or endogenous immune response. Overwhelming ROS levels induced cancer cell death through the dysregulation of ROS-sensitive glycolytic enzymes, leading to the catastrophic depression of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), which are critical for cancer survival and progression.

metabolic reprogramming

oxidative stress

1. Introduction

Redox homeostasis is essential to maintain the normal structure and functions of cellular components, but oxidative stress frequently occurs in cancer cells as a result of oncogene activation, hypoxia, inflammation, and therapeutics [1][2][3][4]. Abrupt accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has detrimental effects on various components of cancer cells, leading to cellular dysfunction or even cell death [5][6][7][8]. In particular, metabolic enzymes are sensitive to ROS, with the most noted examples being glyceraldehyde-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in the glycolytic pathway [9]. The wide application of 2-flourine-18[(18)F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET–CT) demonstrated the glycolytic phenotype in most cancers. Therefore, ROS-induced oxidation and inactivation of GAPDH and PKM2 can cause the depression of both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis, leading to decreased proliferation and/or cell death due to shortages of energy and tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA)-derived biosynthesis, especially in cancer cells in early stages that are more dependent on glycolysis [10][11][12]. Despite these reports linking overt ROS damage to metabolic pathways and other cellular components, it is noteworthy that cancer cells also adapt to such overwhelming ROS levels and metabolic impairment [13][14]. It has been well documented that the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and the synthesis of reduced glutathione (GSH) are enhanced, largely contributing to the production of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and GSH, the most prominent antioxidant molecules [15][16]. On the other hand, cancer cells tend to recruit carbon flux from lipids and glutamine into nucleotide synthesis through the non-oxidative PPP [17][18][19] and into TCA-coupled oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and biosynthesis [20][21], which meet substrate and energy requirements. This relies on the wide crosslinks in the metabolic pathways of glucose, lipids, and amino acids. This metabolic regulation is known to be driven by a complex network consisting of several metabolic modulators, including nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), forkhead box proteins (FOXOs), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), and/or RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinases (AKTs). Their activations depend on ROS levels and their specific inducers, suggesting the heterogeneity of metabolic adaptation under different pro-oxidant conditions.

Accordingly, metabolic regulation plays a central role in cancer adaptation to oxidative stress. Mounting evidence has shown that metabolic regulation, involving the activation of different metabolic modulators with oncogenic properties, metabolic reprogramming, and optimized ROS levels, is tightly linked with cell fate decisions in cancer [22][23][24][25]. A better understanding of how cancer cells orchestrate these metabolic modulators to achieve stress adaptation has potential implications for developing redox- and metabolism-targeting therapeutic strategies.

2. Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells

Oxidative stress in cancer cells is induced by various endogenous or exogenous pro-oxidant elements, such as hypoxia, inflammation, and numerous therapeutics. Upon these stimuli, overwhelming ROS may be produced through a host of oxidoreductases in several compartments of cells, primarily including mitochondria, cytoplasm, and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), inter alia [6][26].

Mitochondria contribute the most to both physiologically and pathologically endogenous ROS [9][27][28]. Numerous studies have revealed that cancer cells exhibit remarkable plasticity in metabolic phenotypes [29][30], with the most notable example being glucose catabolism, which impacts endogenous ROS generation [31][32]. The selective switch to anaerobic glycolysis in rapidly proliferating cancer cells, even under sufficient nutrition and O2 (Warburg effect), favors the acquisition of a ‘pro-oxidant state’ partly due to the diversion of pyruvate away from the mitochondria [33][34][35]. Despite the previously held notion that cancer cells selectively rely on the Warburg effect, there is ample evidence to indicate that cancer cells can switch between glycolysis and OXPHOS to cater to impending energy demands [33][34][36]. To this end, high OXPHOS-coupled aerobic glycolysis is also a potential source of increased ROS levels in cancer cells [37][38][39]. For example, CEM leukemia and HeLa cervical cancer cells overexpressing BCL-2 were shown to have increased OXPHOS and mitochondrial ROS generation [40][41][42]. This suggests that both hypo-functional and/or hyper-functional mitochondria are linked to the increased generation of ROS. Intriguingly, various antitumor drugs, as well as radiation, induce significant oxidative distress in cancer cells [43][44][45][46], due in part to the impairment of mitochondrial function and metabolism [40][45][47] (Figure 1). For example, the doxorubicin, bleomycin, or platinum coordination complexe causes mitochondrial DNA damage or prevent DNA synthesis by inducing cellular oxidative distress [47][48]. Furthermore, genetically unstable clones generated upon irradiation also displayed higher intracellular ROS levels, potentially due to reduced mitochondrial activity and respiration [49][50]. In addition, cancer cells under hypoxia are associated with an increase in ROS, likely because of the deficiency in O2 that prevents electron transfer across the mitochondrial complexes, thereby increasing the possibility of electron leakage to generate ROS [27][51][52]. These findings indicate that the plasticity of mitochondrial function, under the control of various pro-oxidant elements, contributes significantly to ROS regulation in cancer cells.

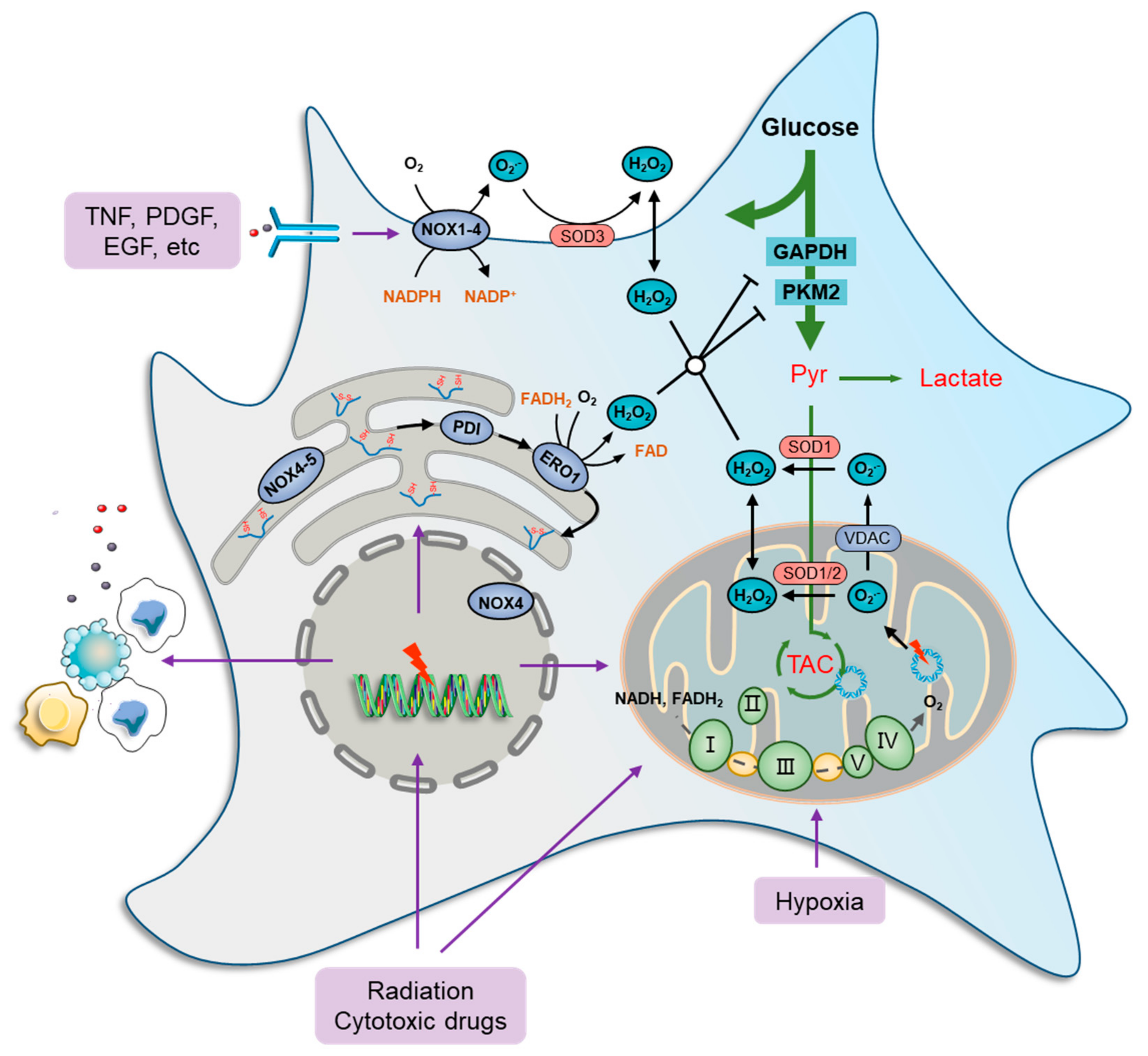

Figure 1. Oxidative stress and metabolic impairment in cancer cells. Mitochondria contribute the most to both physiology- and pathology-derived ROS, of which a fraction is generated by tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) enzymes, while the major portion is produced along the electron transport chain (ETC) due to electron leakage at complexes I, II, and III. NOXs are another major source of ROS production in cancer cells. These ROS-generating enzymes function by transmitting one electron from cytosolic NADPH to O2 to produce a superoxide anion radical (O2•−) that can be transformed to H2O2 immediately by superoxide dismutase (SOD) families. There are seven human NOX homologues, NOX1–5, dual oxidase 1 (DUOX1), and DUOX2, distributed at the cell membrane, mitochondria, ER, and nucleus. They can be activated by a wide variety of ligands, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), angiotensin II, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and pro-epidermal growth factor (EGF). The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) serves as a repository wherein nascent proteins are folded and modified, in which disulfide bond formation is essential for the primary structure of proteins and is catalyzed by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), which can be reduced by ER oxidoreductases, represented by oxidoreductase 1 (ERO1), to generate H2O2 as a byproduct. Furthermore, several glycolytic enzymes are vulnerable to elevated ROS levels and can be inactivated by redox modification, such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and pyruvate kinase M2 isoform (PKM2), which collaboratively cause metabolic stress characterized by a deficiency of carbon sources for ATP generation, lactate secretion, and TCA-driven anabolic biosynthesis.

Cytoplasmic ROS-producing enzymes are represented by members of the NADPH oxidase (NOX) family, such as NOX1-4, whereby cancer cells respond to various extra-cellular stimuli [53][54]. Several studies have shown the role of ROS generation in cancer cells, particularly from the standpoints of oncogene activation, chemoresistance, survival, inflammation, and metastasis. For instance, NOXs can be activated by a wide variety of ligands, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), angiotensin II, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and pro-epidermal growth factor (EGF) [55][56] (Figure 1). Furthermore, the function of NOX1 in generating superoxide anion radicals (O2•−) was shown to be critical in RAS-mediated cell transformation [57]. Similarly, the introduction of the dominant negative mutant (N17) of GTPase RAC1, a subunit of NOX, reduced superoxide levels, thus inhibiting the growth of mutant KRAS-driven cells [58].

The ER is also a ROS factory where nascent proteins are folded and modified to become functional [59]. Disulfide bond formation is essential for the primary structure of proteins and is catalyzed by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI). In a normal state, the oxidized PDI can be reduced by ER oxidoreductases, represented by oxidoreductase 1 (ERO1), to generate H2O2 as a byproduct [60], which maintains a high basic level of ROS in ER [61][62]. Furthermore, ROS production and release from the ER are significantly increased during ER stress [63][64]. When misfolded proteins accumulate beyond a tolerable threshold within the ER, an unfolded protein response (UPR) is induced to mobilize protein-folding capacity and otherwise to promote cell apoptosis [60][65]. ER stress is frequently documented in chemotherapies and radiotherapies because DNA and enzyme damage basically produce a large amount of abnormal proteins [66][67]. In addition, NOX4 and NOX5 were found in the ER and act, in a way, as their cytoplasmic members. However, the restoration of ROS levels with the endogenous antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) did not significantly prevent cancer cell death [68], indicating that ER stress-derived ROS seldom causes cancer cell death directly.

References

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709.

- Obrador, E.; Salvador, R.; López-Blanch, R.; Jihad-Jebbar, A.; Alcácer, J.; Benlloch, M.; Pellicer, J.A.; Estrela, J.M. Melanoma in the liver: Oxidative stress and the mechanisms of metastatic cell survival. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 71, 109–121.

- Chong, S.J.F.; Lai, J.X.H.; Qu, J.; Hirpara, J.; Kang, J.; Swaminathan, K.; Loh, T.; Kumar, A.; Vali, S.; Abbasi, T.; et al. A feedforward relationship between active Rac1 and phosphorylated Bcl-2 is critical for sustaining Bcl-2 phosphorylation and promoting cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2019, 457, 151–167.

- Chong, S.J.F.; Marchi, S.; Petroni, G.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L.; Pervaiz, S. Noncanonical Cell Fate Regulation by Bcl-2 Proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 537–555.

- Kroemer, G.; Galassi, C.; Zitvogel, L.; Galluzzi, L. Immunogenic cell stress and death. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 487–500.

- Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nat. Cancer 2022, 22, 280–297.

- Tang, J.-Y.; Ou-Yang, F.; Hou, M.-F.; Huang, H.-W.; Wang, H.-R.; Li, K.-T.; Fayyaz, S.; Shu, C.-W.; Chang, H.-W. Oxidative stress-modulating drugs have preferential anticancer effects—Involving the regulation of apoptosis, DNA damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, metabolism, and migration. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 58, 109–117.

- Robinson, N.; Ganesan, R.; Hegedűs, C.; Kovács, K.; Kufer, T.A.; Virág, L. Programmed necrotic cell death of macrophages: Focus on pyroptosis, necroptosis, and parthanatos. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101239.

- Wang, K.; Jiang, J.; Lei, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wei, Y.; Huang, C. Targeting Metabolic–Redox Circuits for Cancer Therapy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44, 401–414.

- Faubert, B.; Solmonson, A.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression. Science 2020, 368, eaaw5473.

- Huang, H.; Tang, S.; Ji, M.; Tang, Z.; Shimada, M.; Liu, X.; Qi, S.; Locasale, J.W.; Roeder, R.G.; Zhao, Y.; et al. p300-Mediated Lysine 2-Hydroxyisobutyrylation Regulates Glycolysis. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 663–678.e6.

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, F.; Chen, C.; Liu, P.; Ren, Y.; Sun, P.; Wang, Z.; You, Y.; Zeng, Y.-X.; et al. DHHC9-mediated GLUT1 S-palmitoylation promotes glioblastoma glycolysis and tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5872.

- Qian, X.; Nie, X.; Yao, W.; Klinghammer, K.; Sudhoff, H.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Albers, A.E. Reactive oxygen species in cancer stem cells of head and neck squamous cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 248–257.

- Takahashi, N.; Chen, H.-Y.; Harris, I.S.; Stover, D.G.; Selfors, L.M.; Bronson, R.T.; Deraedt, T.; Cichowski, K.; Welm, A.L.; Mori, Y.; et al. Cancer Cells Co-opt the Neuronal Redox-Sensing Channel TRPA1 to Promote Oxidative-Stress Tolerance. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 985–1003.

- Harris, I.S.; DeNicola, G.M. The Complex Interplay between Antioxidants and ROS in Cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 440–451.

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Duan, R.; Gu, R.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Lian, H.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, A. High- Z -Sensitized Radiotherapy Synergizes with the Intervention of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway for In Situ Tumor Vaccination. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2109726.

- Hoxhaj, G.; Manning, B.D. The PI3K–AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 74–88.

- Shukla, S.K.; Purohit, V.; Mehla, K.; Gunda, V.; Chaika, N.V.; Vernucci, E.; King, R.J.; Abrego, J.; Goode, G.D.; Dasgupta, A.; et al. MUC1 and HIF-1alpha Signaling Crosstalk Induces Anabolic Glucose Metabolism to Impart Gemcitabine Resistance to Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 71–87.e7.

- Puca, F.; Yu, F.; Bartolacci, C.; Pettazzoni, P.; Carugo, A.; Huang-Hobbs, E.; Liu, J.; Zanca, C.; Carbone, F.; Del Poggetto, E.; et al. Medium-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Protects Mitochondria from Lipid Peroxidation in Glioblastoma. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2904–2923.

- Stegen, S.; van Gastel, N.; Eelen, G.; Ghesquière, B.; D’Anna, F.; Thienpont, B.; Goveia, J.; Torrekens, S.; Van Looveren, R.; Luyten, F.P.; et al. HIF-1α Promotes Glutamine-Mediated Redox Homeostasis and Glycogen-Dependent Bioenergetics to Support Postimplantation Bone Cell Survival. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 265–279.

- Yang, W.-H.; Qiu, Y.; Stamatatos, O.; Janowitz, T.; Lukey, M.J. Enhancing the Efficacy of Glutamine Metabolism Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Trends Cancer 2021, 7, 790–804.

- Ludikhuize, M.M.C.; Colman, M.J.R. Metabolic Regulation of Stem Cells and Differentiation: A Forkhead Box O Transcription Factor Perspective. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 1004–1024.

- Green, C.L.; Lamming, D.W.; Fontana, L. Molecular mechanisms of dietary restriction promoting health and longevity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 56–73.

- Schmidlin, C.J.; Shakya, A.; Dodson, M.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. The intricacies of NRF2 regulation in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 76, 110–119.

- Sen, A.; Anakk, S. Jekyll and Hyde: Nuclear receptors ignite and extinguish hepatic oxidative milieu. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 790–802.

- Yun, C.; Lee, S.-H.; Ryu, J.; Park, K.; Jang, J.-W.; Kwak, J.; Hwang, S. Can Static Electricity on a Conductor Drive a Redox Reaction: Contact Electrification of Au by Polydimethylsiloxane, Charge Inversion in Water, and Redox Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14687–14695.

- Sabharwal, S.S.; Schumacker, P.T. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: Initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles’ heel? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 709–721.

- Foo, J.; Bellot, G.; Pervaiz, S.; Alonso, S. Mitochondria-mediated oxidative stress during viral infection. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 30, 679–692.

- Quintanal-Villalonga, A.; Chan, J.M.; Yu, H.A.; Pe’Er, D.; Sawyers, C.L.; Sen, T.; Rudin, C.M. Lineage plasticity in cancer: A shared pathway of therapeutic resistance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 360–371.

- Williams, E.D.; Gao, D.; Redfern, A.; Thompson, E.W. Controversies around epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity in cancer metastasis. Nat. Cancer 2019, 19, 716–732.

- Sun, N.-Y.; Yang, M.-H. Metabolic Reprogramming and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity: Opportunities and Challenges for Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 792.

- Bhardwaj, V.; He, J. Reactive Oxygen Species, Metabolic Plasticity, and Drug Resistance in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3412.

- Liberti, M.V.; Locasale, J.W. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 211–218.

- Sancho, P.; Burgos-Ramos, E.; Tavera, A.; Kheir, T.B.; Jagust, P.; Schoenhals, M.; Barneda, D.; Sellers, K.; Campos-Olivas, R.; Graña, O.; et al. MYC/PGC-1α Balance Determines the Metabolic Phenotype and Plasticity of Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 590–605.

- Srivastava, N.; Kollipara, R.K.; Singh, D.K.; Sudderth, J.; Hu, Z.; Nguyen, H.; Wang, S.; Humphries, C.G.; Carstens, R.; Huffman, K.E.; et al. Inhibition of Cancer Cell Proliferation by PPARγ Is Mediated by a Metabolic Switch that Increases Reactive Oxygen Species Levels. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 650–661.

- Shulman, R.G.; Rothman, D.L. The Glycogen Shunt Maintains Glycolytic Homeostasis and the Warburg Effect in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 761–767.

- Gentric, G.; Kieffer, Y.; Mieulet, V.; Goundiam, O.; Bonneau, C.; Nemati, F.; Hurbain, I.; Raposo, G.; Popova, T.; Stern, M.-H.; et al. PML-Regulated Mitochondrial Metabolism Enhances Chemosensitivity in Human Ovarian Cancers. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 156–173.e10.

- Guièze, R.; Liu, V.M.; Rosebrock, D.; Jourdain, A.A.; Hernández-Sánchez, M.; Zurita, A.M.; Sun, J.; Hacken, E.T.; Baranowski, K.; Thompson, P.A.; et al. Mitochondrial Reprogramming Underlies Resistance to BCL-2 Inhibition in Lymphoid Malignancies. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 369–384.e13.

- Sies, H.; Belousov, V.V.; Chandel, N.S.; Davies, M.J.; Jones, D.P.; Mann, G.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Winterbourn, C. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 499–515.

- Chen, Z.X.; Pervaiz, S. Bcl-2 induces pro-oxidant state by engaging mitochondrial respiration in tumor cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1617–1627.

- Chen, Z.X.; Pervaiz, S. Involvement of cytochrome c oxidase subunits Va and Vb in the regulation of cancer cell metabolism by Bcl-2. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 17, 408–420.

- Velaithan, R.; Kang, J.; Hirpara, J.L.; Loh, T.; Goh, B.C.; Le Bras, M.; Brenner, C.; Clement, M.-V.; Pervaiz, S. The small GTPase Rac1 is a novel binding partner of Bcl-2 and stabilizes its antiapoptotic activity. Blood 2011, 117, 6214–6226.

- Li, X.-X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Shi, G.-Y.; Yi, J.; Wang, J. Emodin as an Effective Agent in Targeting Cancer Stem-Like Side Population Cells of Gallbladder Carcinoma. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 554–566.

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yin, X.; Shi, G.; Li, H.; Hu, Z.; Liang, X. Emodin enhances cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity in human bladder cancer cells through ROS elevation and MRP1 downregulation. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 578.

- Ping, Z.; Peng, Y.; Lang, H.; Xinyong, C.; Zhiyi, Z.; Xiaocheng, W.; Hong, Z.; Liang, S. Oxidative Stress in Radiation-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 3579143.

- Xu, J.; Ji, L.; Ruan, Y.; Wan, Z.; Lin, Z.; Xia, S.; Tao, L.; Zheng, J.; Cai, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. UBQLN1 mediates sorafenib resistance through regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and ROS homeostasis by targeting PGC1β in hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 190.

- Yang, H.; Villani, R.M.; Wang, H.; Simpson, M.J.; Roberts, M.S.; Tang, M.; Liang, X. The role of cellular reactive oxygen species in cancer chemotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 266.

- Mizutani, H.; Tada-Oikawa, S.; Hiraku, Y.; Kojima, M.; Kawanishi, S. Mechanism of apoptosis induced by doxorubicin through the generation of hydrogen peroxide. Life Sci. 2005, 76, 1439–1453.

- Kim, G.J.; Fiskum, G.M.; Morgan, W.F. A Role for Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Perpetuating Radiation-Induced Genomic Instability. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10377–10383.

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Gu, G.; Guo, X.; He, C.; Sun, J.; Zou, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; et al. Pulmonary Delivery of Theranostic Nanoclusters for Lung Cancer Ferroptosis with Enhanced Chemodynamic/Radiation Synergistic Therapy. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 963–972.

- Willson, J.A.; Arienti, S.; Sadiku, P.; Reyes, L.; Coelho, P.; Morrison, T.; Rinaldi, G.; Dockrell, D.H.; Whyte, M.K.B.; Walmsley, S.R. Neutrophil HIF-1α stabilization is augmented by mitochondrial ROS produced via the glycerol 3-phosphate shuttle. Blood 2022, 139, 281–286.

- Tang, K.; Zhu, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Zeng, L.; Chen, C.; Tang, L.; Zhou, L.; Wei, K.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Hypoxia Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Growth by Activating a Glycogen Metabolic Program. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 4949–4963.

- Demelash, A.; Pfannenstiel, L.W.; Liu, L.; Gastman, B.R. Mcl-1 regulates reactive oxygen species via NOX4 during chemotherapy-induced senescence. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28154–28168.

- Parascandolo, A.; Laukkanen, M.O. Carcinogenesis and Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling: Interaction of the NADPH Oxidase NOX1–5 and Superoxide Dismutase 1–3 Signal Transduction Pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 30, 443–486.

- Labrousse-Arias, D.; Martínez-Ruiz, A.; Calzada, M.J. Hypoxia and Redox Signaling on Extracellular Matrix Remodeling: From Mechanisms to Pathological Implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 27, 802–822.

- Lei, X.G.; Zhu, J.-H.; Cheng, W.-H.; Bao, Y.; Ho, Y.-S.; Reddi, A.R.; Holmgren, A.; Arnér, E. Paradoxical Roles of Antioxidant Enzymes: Basic Mechanisms and Health Implications. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 307–364.

- Park, M.-T.; Kim, M.-J.; Suh, Y.; Kim, R.-K.; Kim, H.; Lim, E.-J.; Yoo, K.-C.; Lee, G.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Hwang, S.-G.; et al. Novel signaling axis for ROS generation during K-Ras-induced cellular transformation. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1185–1197.

- Du, J.; Liu, J.; Smith, B.J.; Tsao, M.S.; Cullen, J.J. Role of Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase in the growth of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2010, 18, 135–143.

- Ma, H.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Long, S.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Shi, C.; Sun, W.; Du, J.; et al. ER-Targeting Cyanine Dye as an NIR Photoinducer to Efficiently Trigger Photoimmunogenic Cancer Cell Death. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3477–3486.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, L.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C. Redox signaling and unfolded protein response coordinate cell fate decisions under ER stress. Redox Biol. 2018, 25, 101047.

- Araki, K.; Iemura, S.-I.; Kamiya, Y.; Ron, D.; Kato, K.; Natsume, T.; Nagata, K. Ero1-α and PDIs constitute a hierarchical electron transfer network of endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductases. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 861–874.

- Enyedi, B.; Várnai, P.; Geiszt, M. Redox State of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Is Controlled by Ero1L-alpha and Intraluminal Calcium. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 721–729.

- Peiris-Pagès, M.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. Metastasis and Oxidative Stress: Are Antioxidants a Metabolic Driver of Progression? Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 956–958.

- Fendt, S.-M.; Lunt, S.Y. Dynamic ROS Regulation by TIGAR: Balancing Anti-cancer and Pro-metastasis Effects. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 141–142.

- Haynes, C.M.; Titus, E.A.; Cooper, A.A. Degradation of Misfolded Proteins Prevents ER-Derived Oxidative Stress and Cell Death. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 767–776.

- Ma, M.K.F.; Lau, E.Y.T.; Leung, D.H.W.; Lo, J.; Ho, N.P.Y.; Cheng, L.K.W.; Ma, S.K.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Copland, J.A.; Ding, J.; et al. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase regulates sorafenib resistance via modulation of ER stress-induced differentiation. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 979–990.

- Logothetis, C.; Aparicio, A.; Thompson, T.C. ER stress in prostate cancer: A therapeutically exploitable vulnerability? Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaat3975.

- Hetz, C. The unfolded protein response: Controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 89–102.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

25 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No