Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Hu, X.; Li, G.; Wu, S. Diagnosis for Bladder Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25446 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Hu X, Li G, Wu S. Diagnosis for Bladder Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25446. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Hu, Xinzi, Guangzhi Li, Song Wu. "Diagnosis for Bladder Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25446 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Hu, X., Li, G., & Wu, S. (2022, July 22). Diagnosis for Bladder Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25446

Hu, Xinzi, et al. "Diagnosis for Bladder Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

Bladder cancer (BCa) is one of the most common and expensive urinary system malignancies for its high recurrence and progression rate. In recent years, immense amounts of studies have been carried out to bring a more comprehensive cognition and numerous promising clinic approaches for BCa therapy. The development of innovative enhanced cystoscopy techniques (optical techniques, imaging systems) and tumor biomarkers-based non-invasive urine screening (DNA methylation-based urine test) would dramatically improve the accuracy of tumor detection, reducing the risk of recurrence and progression of BCa.

bladder cancer

diagnosis

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BCa) is one of the most common urinary system malignancies, with an estimated 80,000 new cases and 17,980 deaths worldwide in 2020 [1][2]. BCa can be mainly decided into non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) according to the degree of tumor invasion. Among them, patients with NMIBC account for nearly 80% of cases initially diagnosed and are prone to suffer a risk of recurrence (~70%) and progression (~15%) after standard treatment of clinical guidelines. Approximately 25% patients are diagnosed with MIBC (T2a–T4b), the majority of them presenting with primary invasive BCa and a poor prognosis [3]. The high recurrence and progression rate of BCa aggravates the costly burden of patients for multiple tests and treatments.

Urinary cytology and cystoscopy are the first-line approaches for the diagnosis of BCa. Cystoscopy is applied for the definitive diagnosis and surveillance of BCa, which also commonly suffers from infection and prostate injury in its invasive manner. Thus, the non-invasive testing technology with high specificity and sensitivity is urgently needed. Both the combination of optical techniques and novel imaging systems enhance diagnostic accuracy and reduce the risk. Moreover, urine-based non-invasive screening tests have become the hotspot of current research in recent years. Several urinary biomarkers have been developed for surveillance to avoid repetitious cystoscopy. Among them, six urine test markers (NMP22 BC, NMP22 BladderChek, BTA Stat, BTA TRAK, UroVysion, uCyt+/ImmunoCyt) have been applied for the clinical diagnosis of BCa and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

However, few of them are widely administrated in clinical practice for the limited specificity and equivocal clinical benefit [4][5]. To overcome such limitations, more urine-based non-invasive screening tests and tumor-associated biomarkers were discovered, including urine-derived protein, DNA methylation-based markers, and extracellular vesicles (EVs), promising approaches to decrease follow-up examination, providing additional feasibility in improving the diagnostic efficiency of BCa.

Intravesical instillation of chemotherapeutics or immunological pharmaceuticals after transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) is commonly performed as adjuvant therapy for NMIBC [6], which has been proved to be an effective way to eliminate the residual tumor cells after operation to avoid recurrence [7]. Strategies for MIBC include neoadjuvant therapy, radiotherapy, radical cystectomy (RC), or partial cystectomy [2]. Although the above clinical interventions could partly alleviate the tumor recurrence and progression, a large proportion of patients deteriorate into high-grade or metastatic disease, suffering from cisplatin-based cytotoxic chemotherapy with a poor prognosis (5-year progression rates range from 0.8% to 45%) [2][8]. Novel therapies, including tumor-targeted drugs, antibody conjugated drugs, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and vaccines, have been developed to meet the treatment needs of patients with BCG failures. In addition, abundant novel drug delivery carriers have been designed to improve the efficacy of instillation therapy. For patients with advanced BCa, improved neoadjuvant therapy and novel therapeutic modalities play an active role in clinical management [2].

2. Diagnosis

2.1. Optical Techniques and New Imaging Systems

With standard white-light cystoscopy (WLC), it is easy to miss the minimal residual tumor tissues during the diagnostic detection and resection of carcinoma in situ (CIS) [9]. To overcome this dilemma, diagnostic technology is constantly being upgraded, where laser-induced fluorescence (LIF), autofluorescence cystoscopy (AFC), and photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) are becoming the focus of attention.

2.1.1. Photodynamic Diagnosis

PDD involves the instillation of a photosensitizer (5-ALA: 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HAL: hexaminolevulinate) into the bladder before cystoscopy. Tumor cells absorb the photosensitizers and show red fluorescence under blue light (380–450 nm) exposure based on the different enzymatic activity between malignant and benign tissues, which is helpful in distinguishing tumor cells from para-cancer tissues [10] (Figure 1). A previous meta-analysis from Xiong et al. noted the tumor recurrence rate in the 5-ALA- based PDD group is significantly lower than that in the HAL-PDD group (Odds ratio [OR]: 0.48, 95% CI [confidence interval]: 0.26–0.95) [11][12]. Burger et al. reported that the detection rate of CIS lesions by PDD was 40.8%, which is higher than that by WLC [9]. According to a meta-analysis by Russo et al., PDD also showed a higher diagnostic OR and sensitivity than WLC [10].

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the mechanism of PDD. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [13], Copyright (2021) Sasaki et al.

TURBT combined with PDD can maximize the tumor resection rate to reduce the recurrence of BCa. The prospective evaluation study of PDD for NMIBC surveillance noted that 33% of additional cancers were detected by PDD, and the recurrence rate of NMIBC detected and resected by PDD was lower than that by WLC [14]. This result is consistent with the findings of the recurrence-focused randomized study from Drejeret al. The use of cystoscopy-based PDD for NMIBC surveillance after the first-time TURBT reduced the risk of recurrence with an OR of 0.67 (p = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.48–0.95) [15]. According to a systematic review by Veeratterapillay et al., 2288 patients from 12 randomized controlled trials were included in the meta-analysis, which found that PDD reduced recurrence rate and improved recurrence-free survival (RFS) (68.2% vs. 57.3%) for NMIBC over at least a 2-year follow-up period compared with WLC [16]. Motlagh et al. noted that PDD combined with immediate intravesical chemotherapy resulted in an additional 32% reduction OR for the 12-month recurrence risk [17].

2.1.2. Fluorescence Cystoscopy

Similar to PDD, LIF is involved in light emission and excitation, as well as the absorption of endogenous porphyrin compounds. The difference in spectra is mainly the result of cellular oxygenation processes and reduction between tumor cells and normal tissues, as evidenced by changes in the NAD to NADH ratio [18]. For the past years, AFC was commonly applied as a complementary tool to standard cystoscopy. Optical filters and algorithms convert images into spatial maps of the intensity of autofluorescence, which can significantly improve sampling accuracy of tissue biopsies and pathology examinations. The Onco-LIFE system (photo-induced fluorescence endoscopy) provides an objective comparison of green and red self-fluorescence by calculating a ratio (NCV: numerical color value), which enables precise localization of small pathological changes [18][19]. Compared to WLC, AFC and PDD exhibit higher sensitivity and better ability to perform biopsies.

2.1.3. Optical Biopsy Techniques

Some optical biopsy techniques, including optical coherence tomography (OCT) and confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE), involve specific wavelengths of light and cystoscopy in dynamic real-time images of tissue for the surveillance of BCa [19][20]. Sonn et al. suggested that CLE is an effective aid to cystoscopy using dye fluorescein and light from a 488 nm laser fiber optic source to provide real-time dynamic images of malignant cells and normal tissues [21].

Similarly, OCT utilizes near-infrared light (890–1300 nm) to scatter tissue layers, providing tissue images with a penetration depth of 2 mm and a spatial resolution of 10–20 μm. The measurement of light scattering is performed by comparing a back-scattered or back-reflected light signal to a reference signal, which is highly sensitive and specific to identify malignant lesions [22]. According to a meta-analysis by Brunckhorst et al., OCT could remarkably improve overall diagnostic accuracy with a specificity of 60–98.5% and a sensitivity of 74.5–100% [20]. A meta-analysis of OCT for BCa identification by Xiong et al. noted that the sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUC) were 94.9% (95% CI: 92.7–96.6%), 84.6% (95% CI: 82.6–86.4%), and 0.97, respectively [23].

In addition, some novel spectral and imaging techniques have been introduced into diagnosing BCa, including diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, elastic light scattering, vibrational spectroscopy, biophotonic methods, multi-photon microscopy, and scanning fiber endoscopy [19][20]. Overall, combinations of imaging modalities offer higher quality benefits than diagnostic methods alone, such as PDD and NBI, PDD and CLE, as well as CLE and OCT, have been considered. Schmidbauer et al. evaluated 66 patients with suspected BCa by using WLC, PDD, and PDD combined with OCT. The result showed an increase in sensitivity from 89.7% to 100% and specificity from 62% to 87% [22].

2.1.4. Imaging

Similar to PDD, NBI (narrow-band imaging) provides a three-dimensional image of the bladder to distinguish between intensive vascular tumors and normal tissues. NBI is a novel cystoscopy-aid imaging strategy [9][10]. Kutwin et al. reported that the sensitivity of NBI for BCa detection was 94–97.9%, compared with WLC (87–88.8%). Moreover, the sensitivity of NBI for CIS was remarkably superior to WLC (93–100% vs. 66.7–77%) [9]. In a recent meta-analysis, the additional detection rate of NBI for NMIBC showed 18.6% greater than that of WLC [10]. However, no significant difference between PDD and NBI in sensitivity and specificity was found in current studies. Both effective methods increase the visibility of cystoscopy and can prolong the follow-up interval of recurrence or progression [10][24][25].

As auxiliary strategies, cross-sectional urography, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is commonly used to detect large masses or invasive tumors in the upper urinary tract [26][27]. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) provide valuable methods for distinguishing between peripheral tissue and tumor invasion [19]. DWI is a non-invasive functional imaging method that has been widely used for histological grading and radio sensitivity examination in malignant tumors [28][29]. The DWI signal is assessed by visual image interpretation and the quantitative analysis of ADC, and local staging is performed based on the difference in signal intensity [28][29]. Texture analysis of ADC maps and texture features selection predict chemoradiotherapy response and identify the classification of pathological tumor response in MIBC [29]. DWI plays a potential role as a functional magnetic resonance imaging technique for the qualitative and quantitative detection of BCa. Yoshida et al. reported that the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of DWI for the diagnosis of BCa were 91–100%, 77–91%, and 81–96%, respectively [28]. However, inflammatory and granulomas may appear high-intensity DWI signals as well, leading to the risk of false-positives [28]. Moreover, Cai et al. reported that the overall diagnosis of histological grading for BCa with synthetic MRI-derived parameters was inferior to ADC. Still, the efficiency of the former was much better than that of ADC due to multiple contrast-weighted images and quantification maps generated in a single scan [30].

There is also a potential role for emerging computer-based systems in BCa diagnosis. The CAD system, a multi-parametric computer-aided diagnosis system based on magnetic resonance T2W imaging and DWI, is applied for diagnostic differentiation of BCa staging, especially T1 and T2 stages. Hammouda et al. reported that the total area under accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of CAD system were 95.24%, 95.24%, and 95.24%, respectively [31].

VI-RADS (Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System), a novel multi-parametric system, was developed to standardize the reporting and staging of preoperative multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging of BCa, which involves T2W imaging, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, and DWI [2][32][33][34]. The VI-RADS scores are based on the signal intensity of T2W imaging, DWI, ADC, and dynamic contrast enhancement (DCE) MRI in different layers of the bladder wall. According to a retrospective study by Meng et al., the overall AUC value of VI-RADS was 0.939 with a cutoff value of 3 or greater [33]. In a meta-analysis included six studies with more than 1000 patients, the sensitivity and specificity of detection for MIBC by VI-RADS were 0.90 (95% CI: 0.86–0.94) and 0.86 (95% CI: 0.71–0.94), respectively [35]. Moreover, Ahn et al. noted that tumor contact length could be used as a complementary indicator for VI-RADS to predict MIBC at a threshold of 3 cm to reduce the false-positive rate [36]. A single-center retrospective study showed that the specificity of the integration of VI-RADS and tumor contact length was 82.46–87.72%, and the PPV was 90.91–91.59%, indicating an effective strategy to reduce the false-positive rate of VI-RADS [37]. Feng et al. proved that the integration of fractional-order calculus model and VI-RADS increased the AUC value from 0.859 to 0.931, which helped to identify and stage BCa [38]. Thus, VI-RADS may be the most useful method in accelerating radical treatment and determining response to bladder preservation methods for NMIBC [34].

2.1.5. Ultrasound

Ultrasound is an effective method for BCa detection. The 29 mhz high-resolution micro-ultrasound (mUS) technique has been suggested as an alternative method for detecting BCa and differentiating between NMIBC and MIBC, which provides real-time images and a cost effectiveness approach. A comparison study of the diagnostic accuracy of mUS vs. MRI in distinguished NMIBC and MIBC at definitive pathological examination. The sensitivity, specificity of mUS and MRI were 85.0% vs. 76.3% and 85.0% vs. 50.0%, respectively [39].

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) is another novel ultrasound techniques, which is used for the differentiation of high- and low-grade urothelial carcinoma. A sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 90% were obtained for high-grade tumors, while a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 89% were obtained for low-grade BCa [40]. Moreover, Li et al. introduced a combination diagnosis of CEUS and MRI+DWI, and the accuracy of the combination diagnosis was higher than that of the single diagnostic methods [41].

2.1.6. Novel Diagnostic Systems

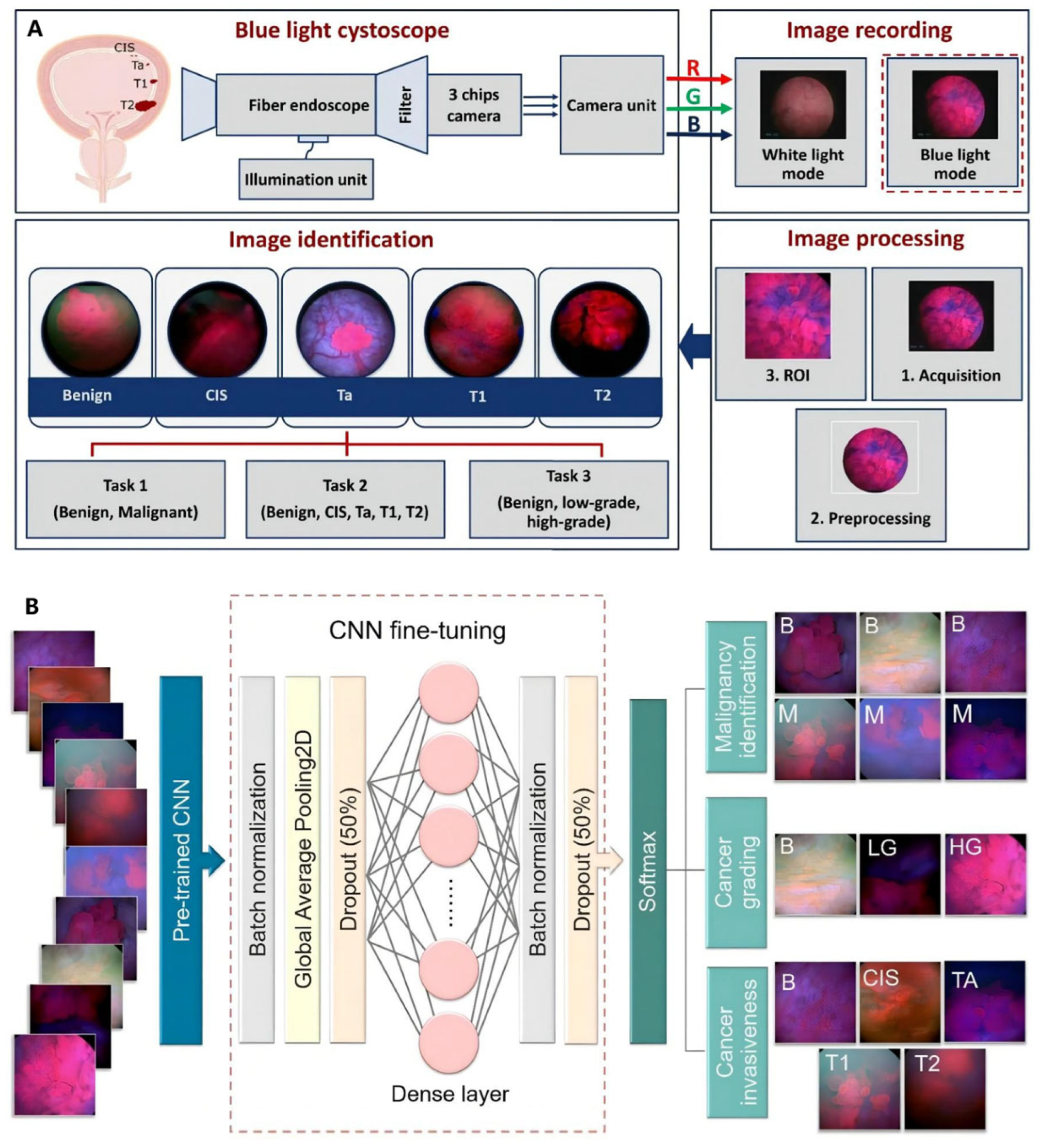

In recent years, studies have involved artificial intelligence (AI) models in diagnostic methods for BCa. Deep learning is a new area of AI, which has been introduced in BCa management, including automated tumor detection, staging and grading, bladder wall segmentation, and tasks such as recurrence prediction, chemotherapy response, and overall survival evaluation. Shkolyar et al. developed a convolutional neural network-based image analysis platform (CystoNet) for the automatic detection of BCa with a sensitivity of 90.9% (95% CI: 90.3–91.6%) and a specificity of 98.6% (95% CI: 98.5–98.8%) [42]. Ali et al. introduced an AI diagnostic platform, which depended on four pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNN) to predict the malignancy, invasiveness, and grading of the images with a sensitivity of 95.77% and a specificity of 87.84%, respectively [43]. The classification pipeline for AI detection of malignant tumor task and the detailed process of it is illustrated in Figure 2. However, the over-diagnosis of AI detection is reported to be concerned. Thus, there is a need to improve recognition and tasks of AI detection, including tumor staging and grading [44].

Figure 2. AI model based on blue light cystoscopy for BCa diagnosis. (A) Overview of image acquisition and image processing using blue light cystoscopy. (B) Schematic diagram of the CNN fine-tuning considered for identifying BCa. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [43], Copyright (2021) Nairveen Ali et al.

At present, many challenges may be faced before these new technologies become mainstream for the equipment requirement. These complementary diagnostic methods bring higher quality for BCa diagnosis, and the perfect optical techniques and imaging systems gradually replace histopathological analysis. To assess the actual value, more random studies are needed to determine the potential of these techniques in BCa diagnosis.

2.2. Urine Tests and Biomarkers

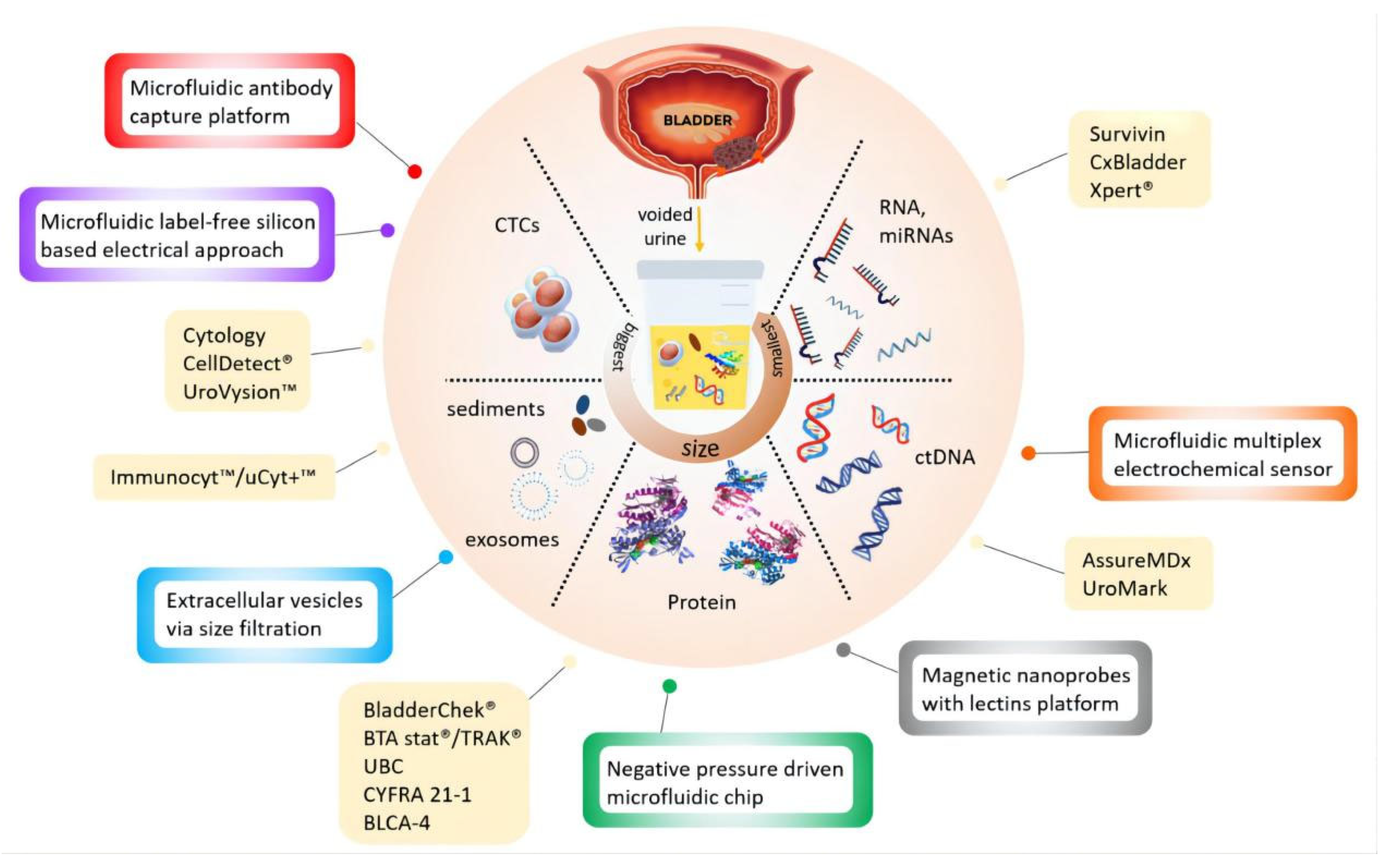

Urine cytology is a commonly used non-invasive test for the clinical management of BCa, which exhibits good sensitivity for CIS and high-grade BCa, while showing poor performance for low-grade tumors. Urine-based non-invasive screening tests have demonstrated superior potential clinical effectiveness, and many biomarkers involving proteins, DNA methylation, and EVs have been discovered. The current urine-based biomarkers and assays refer to Figure 3. Six urine biomarkers approved by FDA have been applied for the diagnosis and monitoring of BCa, including NMP22 BC (nuclear matrix protein 22 ELISA test), NMP22 BladderChek, BTA Stat (qualitative test), BTA TRAK (quantitative test), UroVysion (FISH), and uCyt+/ImmunoCyt (fluorescent immunohistochemistry) (Table 1) [45][46]. The sensitivity of most tests increases with tumor stages or grade, but false positives can occur due to the possibility of inflammation and hematuria. Although their sensitivity is superior to urine cytology, they still have not replaced the current diagnostic criteria of the test [47][48]. Therefore, researchers still need more effective detection methods to detect early and minimal tumors.

Figure 3. Current available (yellow boxes) and potential devices (color bordered boxes) for urinary BCa diagnosis. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [49], Copyright (2020) Kit Man Chan et al.

Table 1. FDA-approved biomarkers and urine protein markers.

| FDA-Approved Biomarkers | Markers | Method | Sensitivity/%(95% CI) | Specificity/%(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMP22 BC | Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein | ELISA | 69 (62–75) | 77 (70–83) |

| NMP22 BladderChek | Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein | Point-of-care test | 58 (52–59) | 88 (87–89) |

| BTA Stat | Complement factor H-related protein | ELISA | 65 (57–82) | 74 (68–93) |

| BTA TRAK | Complement factor H-related protein | Point-of-care test | 64 (66–77) | 77 (5–75) |

| UroVysion | Alt in chromosomes 3, 7, 17, and 9p21 | FISH | 72 (69–87) | 83 (89–96) |

| uCyt+/ImmunoCyt | Carcinoembryonic antigen, bladder tumor cell-associated mucins |

Fluorescent immunohistoche- mistry |

73 (68–77) | 66 (63–69) |

2.2.1. Proteins

Some protein-based biomarkers and assays that have not yet been clinically recommended have also progressed besides NMP22 BC and BTA assays. CYFRA21-1 is a cytokeratin 19 fragment and is reported to be a promising biomarker for diagnosing or monitoring the prognosis of BCa [50]. Matuszczak et al. noted that CYFRA21-1 is highly sensitive for diagnosing CIS and high-grade BCa [51]. According to a meta-analysis by Huang et al., an ELISA test for CYFRA21-1 that detects the soluble fragments of cytokeratin 19 in urine showed the sensitivity and specificity were 82% (95% CI: 0.70–0.90) and 87% (95% CI: 0.84–0.90), respectively [52]. Lei et al. invented a fluorescent nanosphere-based immunochromatographic test strip for CYFRA21-1 with a sensitivity of 92.86% and a specificity of 100% for BCa diagnosis [53].

Urinary Bladder Cancer (UBC) ELISA and UBC immunoradiometry are used to detect the level of cytokeratin 8 and 18 fragments in urine. The results of a meta-analysis by Lu et al. showed the sensitivity and specificity were 59% (95% CI: 55–62%) and 76% (95% CI: 72–80%), respectively [54]. Meisl et al. developed a nomogram based on a multi-center dataset to identify patients with high-risk BCa, and urine was analyzed using the UBC® Rapid test. The results showed that the risk factor-based nomogram had a predictive area of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.72–0.87) and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.92–0.98) for low-grade Bca and high-grade Bca, respectively, which can be a helpful screening tool for NMIBC [55].

Survivin, a member of the apoptosis suppressor gene family, is associated with cell apoptosis, proliferation, cell cycle, angiogenesis, and tumor cell survival. Liang et al. noted that the total sensitivity and specificity of survivin were, respectively, 79% (95% CI: 0.73–0.84) and 87% (95% CI: 0.79–0.92) [56].

BLCA-1 [57] and BLCA-4 [47], two transcription factors of the nuclear matrix protein, have promising prospects in the diagnosis of early tumors with sensitivity and specificity, respectively, 80% and 93% (95% CI: 0.90–0.95) and 87% and 97% (95% CI: 0.95–0.98).

Microchromosome maintenance protein 5 (MCM5) is a crucial factor in DNA replication, located at the basal layer of the epithelium in normal tissues, which would extend to the whole epithelial layer in the tumor situation. A commercial ELISA kit, named ADXBLADDER, was applied for the urine-based non-invasive screening for BCa, depending on the detection of MCM5 level with an overall sensitivity of 44.9% (95% CI: 36.1–54) and specificity of 71.1% (95% CI: 68.5–73.5) [58]. A multi-center study by Roupret et al. demonstrated a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.15% for ADXBLADDER to preclude high-grade/CIS recurrence [59].

URO17 assay is a urine test to detect the level of keratin 17 (K17) in BCa patients with high sensitivity. According to Babu et al. study, the expression of K17 in 112 urine was applied for the BCa diagnosis via immunocytochemistry analysis, with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 96%, respectively [60]. These urine-based assays are more sensitive than urine cytology, but they tend to be less specific and sensitive than WLC for low-grade BCa (30–60%).

Oncuria™, a multiplex immunoassay, was used to detect bladder performance in urine in a multi-institutional cohort study. For a total of 362 prospectively collected subjects evaluated for BCa, Oncuria™ had an overall sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 93%, PPV of 65%, and NPV of 99% [61].

2.2.2. Genomic Biomarkers

Genomic biomarkers have also shown the effectiveness in the diagnosis of BCa. Microsatellite analysis utilizes PCR to analyze DNA mutations in urinary exfoliated cells with an overall sensitivity of 58–92% and a specificity of 73–100% [62]. Telomeric repeat amplification (TRAP) is used to detect telomerase with high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (88%) [63].

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) presents in 70% of NMIBC, and Zuiverloon et al. reported the sensitivity of FGFR3 for detecting recurrence of BCa was 58% [64]. The Quanticyt system could automatically quantitative cell nucleus with a sensitivity of 59% and a specificity of 79%, while little advanced research has been reported in the past decades [65].

According to a study by Lokeshiwar et al., hyaluronic acid- hyaluronidase (HA-HAase) has a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 70% for detecting BCa. Still, the risk of recurrence within five months is high in those with false positives [66]. Over-expression of eukaryotic initiation factor 5A2 (EIF5A2) and the AIB1 gene is associated with postoperative recurrence of BCa [67]. Chen et al. developed a combined EIF5A2, AIB1, and NMP22 assay model with a sensitivity and specificity of 92%, which is superior to single biomarker assays [68].

Cxbladder detects four mRNAs (IGFBP5, HOHA13, MDK, CDK1) in urine to diagnose BCa and monitor recurrence. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and NPV were 91% (95% CI: 0.85–0.95), 61% (95% CI: 0.21–0.90), 16% (95% CI: 0.09–0.28), and 98% (95% CI: 0.82–0.99), respectively, as reported in Laukhtina’s meta-analysis [69].

The XPERT© Bladder Cancer Monitor is a test for detecting the five mRNA sequences (ABL1, CRH, IGF2, UPK1B, ANXA10) in urine [70][71]. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of another urinary biomarker test for XPERT© Bladder Cancer Monitor were 72% (95% CI: 0.63–0.80), 76% (95% CI: 0.72–0.81), 43% (95% CI: 0.32–0.54), and 92% (95% CI: 0.90–0.90), respectively [69]. A prospective study from Singer et al. noted that the XPERT© Bladder Cancer Monitor might provide better sensitivity in the case of high-grade NMIBC recurrence [61].

Moreover, Uromonitor is an effective urinary biomarker test for monitoring BCa recurrence, and its sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were, respectively, 93% (95% CI: 79–98%), 79% (95% CI: 62–90%), 67% (95% CI: 36–89%), and 96% (95% CI: 86–99%). Uromonitor and Cxbladder are not feasible to monitor the recurrence of high-grade BCa due to the lack of data [69] (Table 2).

Table 2. Urinary biomarkers assays for BCa.

| Urinary Biomarker Tests/Biomarkers | Markers | Method | Sensitivity/ %(95% CI) |

Specificity/ %(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYFRA21-1 | Cytokeratin 19 (cytoskeletal protein) | ELISA | 82 (0.70–0.90) | 87 (0.84–0.90) |

| UBC | Cytokeratin 8 and 18 (cytoskeletal proteins) | ELISA | 59 (0.55–0.62) | 76 (0.72–0.80) |

| Survivin | A member of inhibitors of apoptosis gene family | Bio-dot test | 79 (0.73–0.84) | 87 (0.79–0.92) |

| BLCA-1 | Nuclear matrix protein | ELISA | 80 | 87 |

| BLCA-4 | Nuclear matrix protein | ELISA | 93 (0.90–0.95) | 97 (0.95–0.98) |

| ADXBLADDER | Microchromosome maintenance protein 5(MCM5) | ELISA | 44.9 (36.1–54) | 71.1 (68.5–73.5) |

| URO17 | Keratin 17(cytoskeletal proteins ) | Immunocytoche- mistry |

100 | 96 |

| Microsatellite analysis | DNA mutation | PCR | 58–92 | 73–100 |

| TRAP | Telomerase | 90 | 88 | |

| Quanticyt | Cell nucleus | quantitative | 59 | 79 |

| HA-HAase | 91 | 70 | ||

| EIF5A2, AIB1 and NMP22 model | 92 | 92 | ||

| Cxbladder | mRNAs (IGFBP5, HOHA13, MDK, CDK1) | 91 (0.85–0.95) | 61 (0.21–0.90) | |

| Xpert bladder cancer | 72 (0.63–0.80) | 76 (0.72–0.81) | ||

| Uromonitor | 93 (0.79–0.98) | 79 (0.62–0.90) | ||

| Oncuria™ | 93 | 93 |

2.2.3. DNA Methylation

Metabolites can be applied as urinary biomarkers. Several DNA methylation biomarkers are one of the leading research topics. Interestingly, utMeMA, a DNA methylation-based assay for detecting multiple genomic regions of urinary tumors, was reported by Lin and colleagues [72] (Figure 4). DNA methylation markers come from a combined analysis of three cohorts from Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (SYSMH), the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO), and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The integrated analysis of BCa sequencing data from three cohorts identified 26 BCa-specific methylation sites with sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 83.1%, respectively. The utMeMA-based assays have greatly improved the detection sensitivity for early BCa (Ta stage and low-grade BCa) [72].

Figure 4. Study design and workflow of utMeMA. (SYSMH = Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital; TCGA = the Cancer Genome Atlas; BCa = bladder cancer; FDR = false discovery rate; LASSO = the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; RF = random forest). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [72], Copyright (2020) American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Several DNA methylation-based assays have also been reported. Bladder EpiCheck is a DNA methylation profile-based assay that analyzes DNA in spontaneous urine, with a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 74% (95% CI: 57–85%), 84% (95% CI: 80–88%), 48% (95% CI: 42–54%), and 94% (95% CI: 90–97%), respectively [69][73]. Several clinical trials have documented that the Bladder EpiCheck methylation test is an effective method for surveillance of high-risk NMIBC [74][75].

UroMark assay, a bisulphite sequencing assay and analysis pipeline for detecting BCa from urinary sediment DNA with a sensitivity, specificity, and NPV of 98%, 97%, and 97%, respectively [76].

The Bladder CARE test uses methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases to measure the methylation levels of three BCa-specific biomarkers, which had an overall sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 93.5%, 92.6%, 87.8%, and 96.2%, respectively, potentially improving the detection of early BCa [77].

The GynTect® assay, a method based on six DNA methylation-based markers, was initially designed to diagnose cervical cancer and was applied by Steinbach et al. to detect BCa with a sensitivity and specificity of up to 60% and 96.7% [78]. (Table 3).

Table 3. DNA methylation assays and biomarkers for BCa detection.

| Tests | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder EpiCheck | 74 (95% CI: 57–85) | 84 (95% CI: 80–88) | 48 (95% CI: 42–54) | 94 (95% CI: 90–97) |

| UroMark | 98 | 97 | 97 | |

| utMeMA | 90 | 83.1 | >85 | >85 |

| Bladder CARE | 93.5 | 92.6 | 87.8 | 96.2 |

| The GynTect® | 60 | 96.7 |

2.2.4. Extracellular Vesicles

EVs contribute to the development and progression of BCa by influencing the cell cycle, facilitating the epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and forming the tumor mesenchyme. EV-derived macromolecules act at different stages of BCa tumorigenesis [79]. In recent years, many EVs have been discovered and show potential promise for BCa detection. Some genetic substances and EVs, shown in Table 4, have been proved as potential biomarkers. The technical approach for capturing and isolating EVs by double nanofiltration has been developed, with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 90% [80]. Furthermore, several urinary biomarker-based microdevices have been reported, which used microdevice-assisted methods providing real-time detection needed only microliters of urine with the specificity and sensitivity for cancer cells being over 95% [49] (Table 4). In addition, Miyake et al. created a device named cellular fluorescence analysis unit-II (CFAU-II), which introduced cellular fluorescence analysis into urine cytology with an overall sensitivity of 63% (p < 0.001) [81].

Table 4. Non-exhaustive overview of urinary genetic biomarkers and extracellular vesicles biomarkers for BCa [48][82][83].

| Genetic Biomarkers/Markers | Types | |

|---|---|---|

| TERT | DNA mutational analysis | |

| FGFR3 | DNA mutational analysis | |

| Chromosomes | Microsatellite analysis | |

| CDK1, HOXA13, MDK, IGFBP5 | Multigene panels | |

| Lactate, β-hydroxypyruvate, palmitoyl sphingomyelin, phosphocholine, arachidonate, BCAAs, adenosine, succinate | Metabolite biomarkers | |

| Extracellular Vesicles Biomarkers | Types | Purposes |

| Uroplakin-1 | Transitional epithelial cells | Diagnosis |

| Uroplakin-2 | Transitional epithelial cells | Diagnosis |

| TACSTD2 | Protein | Diagnosis |

| EDIL-3 | Protein | Diagnosis |

| Periostin | Protein | Prognosis |

| CD10, CD36, CD44, 5T4, CD147(basigin), CD73(NT5E), integrinβ1, integrinα6, Mucin-1(MUC1) | Protein | Diagnosis |

| Alpha-1-antitrypsin, histone H2B1K | Protein | Diagnosis |

| Resistin, GTPase NRas, EPS8L1, mucin 4, EPS8L2, retinoic acid-induced protein 3, ɑ subunit of GsGTP, binding protein, EH-domain-containing protein 4 | Protein | Diagnosis |

| MAGEB4, NMP-22 | mRNA, Protein | Diagnosis |

| FOLR1, TTP1 | Protein | Diagnosis |

| TACSTD2 | Protein | Diagnosis |

| miR-375, miR-146a | miRNA | Prognosis |

| miR-4454, miR-205-5p, miR-200c-3p, miR-200b-3p, miR-21-5p, miR-29b-3p, miR-720 /3007a | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-200a-3p; miR-99a-5p; miR-141-3p; miR-205-5p | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-15a-5p, miR-31-5p, miR-21, miR-155-5p, miR-132-3p | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-940, miR-191, miR-93, miR-200c, miR-15a, miR-30a-3p, miR-503-5p, Mirlet7b | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-66-3b | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-146-5p, miR-138-5p, miR-144-5p | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-145-5p, miR-23b | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-133b | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-375-3p | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| miR-29c | miRNA | Diagnosis |

| HOTAIR, HOX-AS-2, MALAT1 OCT4, SOX2 | mRNA, lncRNA | Diagnosis |

| UCA1-201, UCA1-203, MALAT1, LINC00355 | lncRNA | Diagnosis |

| SNHG16, Linc-UBC1 | Diagnosis | |

| PCAT-1 | Diagnosis | |

| H19 | Diagnosis | |

| LASS2, GALNT1, FOXO3, ARHGEF3 | mRNA | Diagnosis |

| MDM2, ERBB2, CCND, CCNE1, CDKN2A, PTEN, RB1 | DNA | Diagnosis |

Overall, the non-invasive and highly specific biomarkers in urine have shown great promise in the diagnosis and surveillance of BCa. However, the effectiveness of urine biomarkers for BCa diagnosis is not accurate enough, with ambiguous clinical benefits for early low-grade BCa. Moreover, the concentrations of biomarkers may vary with the organ function and medications. For the facility, parts of biomarkers are needed special techniques, which call for the requirement of highly qualified personnel and comprehensive equipment [84]. In short, the evaluation of the performance of biomarkers requires large prospective multi-center studies for the replacement of cytology.

References

- Richters, A.; Aben, K.K.H.; Kiemeney, L. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer: An update. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 1895–1904.

- Lenis, A.T.; Lec, P.M.; Chamie, K.; Mshs, M.D. Bladder Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 1980–1991.

- Powles, T.; Bellmunt, J.; Comperat, E.; De Santis, M.; Huddart, R.; Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Valderrama, B.P.; Ravaud, A.; Shariat, S.F.; et al. Bladder cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 33, 244–258.

- Henning, G.M.; Barashi, N.S.; Smith, Z.L. Advances in Biomarkers for Detection, Surveillance, and Prognosis of Bladder Cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2021, 19, 194–198.

- Bhatt, J.; Cowan, N.; Protheroe, A.; Crew, J. Recent advances in urinary bladder cancer detection. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2012, 12, 929–939.

- Jordan, B.; Meeks, J.J. T1 bladder cancer: Current considerations for diagnosis and management. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019, 16, 23–34.

- GuhaSarkar, S.; Banerjee, R. Intravesical drug delivery: Challenges, current status, opportunities and novel strategies. J. Control. Release 2010, 148, 147–159.

- Downes, M.R.; Lajkosz, K.; Kuk, C.; Gao, B.; Kulkarni, G.S.; van der Kwast, T.H. The impact of grading scheme on non-muscle invasive bladder cancer progression: Potential utility of hybrid grading schemes. Pathology 2022, 54, 425–433.

- Kutwin, P.; Konecki, T.; Cichocki, M.; Falkowski, P.; Jablonowski, Z. Photodynamic Diagnosis and Narrow-Band Imaging in the Management of Bladder Cancer: A Review. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 459–464.

- Russo, G.I.; Sholklapper, T.N.; Cocci, A.; Broggi, G.; Caltabiano, R.; Smith, A.B.; Lotan, Y.; Morgia, G.; Kamat, A.M.; Witjes, J.A.; et al. Performance of Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) and Photodynamic Diagnosis (PDD) Fluorescence Imaging Compared to White Light Cystoscopy (WLC) in Detecting Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Lesion-Level Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4378.

- Inoue, K.; Fukuhara, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Karashima, T.; Kurabayashi, A.; Furihata, M.; Hanazaki, K.; Lai, H.W.; Ogura, S.I. Current status of photodynamic technology for urothelial cancer. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 392–398.

- Xiong, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, S.; Ge, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, D.; Chen, Q. A meta-analysis of narrow band imaging for the diagnosis and therapeutic outcome of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170819.

- Sasaki, M.; Tanaka, M.; Ichikawa, H.; Suzuki, T.; Nishie, H.; Ozeki, K.; Shimura, T.; Kubota, E.; Tanida, S.; Kataoka, H. 5-aminolaevulinic acid (5-ALA) accumulates in GIST-T1 cells and photodynamic diagnosis using 5-ALA identifies gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) in xenograft tumor models. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249650.

- Lotan, Y.; Chaplin, I.; Ahmadi, H.; Meng, X.; Roberts, S.; Ladi-Seyedian, S.; Bagrodia, A.; Margulis, V.; Woldu, S.; Daneshmand, S. Prospective evaluation of blue-light flexible cystoscopy with hexaminolevulinate in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2021, 127, 108–113.

- Drejer, D.; Moltke, A.L.; Nielsen, A.M.; Lam, G.W.; Jensen, J.B. DaBlaCa-11: Photodynamic Diagnosis in Flexible Cystoscopy-A Randomized Study With Focus on Recurrence. Urology 2020, 137, 91–96.

- Veeratterapillay, R.; Gravestock, P.; Nambiar, A.; Gupta, A.; Aboumarzouk, O.; Rai, B.; Vale, L.; Heer, R. Time to Turn on the Blue Lights: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Photodynamic Diagnosis for Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol. Open Sci. 2021, 31, 17–27.

- Sari Motlagh, R.; Mori, K.; Laukhtina, E.; Aydh, A.; Katayama, S.; Grossmann, N.C.; Mostafai, H.; Pradere, B.; Quhal, F.; Schuettfort, V.M.; et al. Impact of enhanced optical techniques at time of transurethral resection of bladder tumour, with or without single immediate intravesical chemotherapy, on recurrence rate of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. BJU Int. 2021, 128, 280–289.

- Bochynek, K.; Aebisher, D.; Gasiorek, M.; Cieslar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Evaluation of autofluorescence and photodynamic diagnosis in assessment of bladder lesions. Photodiagn. Photodyn Ther. 2020, 30, 101719.

- Bochenek, K.; Aebisher, D.; Miedzybrodzka, A.; Cieslar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Methods for bladder cancer diagnosis—The role of autofluorescence and photodynamic diagnosis. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 141–148.

- Brunckhorst, O.; Ong, Q.J.; Elson, D.; Mayer, E. Novel real-time optical imaging modalities for the detection of neoplastic lesions in urology: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 33, 1349–1367.

- Sonn, G.A.; Jones, S.N.; Tarin, T.V.; Du, C.B.; Mach, K.E.; Jensen, K.C.; Liao, J.C. Optical biopsy of human bladder neoplasia with in vivo confocal laser endomicroscopy. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 1299–1305.

- Schmidbauer, J.; Remzi, M.; Klatte, T.; Waldert, M.; Mauermann, J.; Susani, M.; Marberger, M. Fluorescence cystoscopy with high-resolution optical coherence tomography imaging as an adjunct reduces false-positive findings in the diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur. Urol. 2009, 56, 914–919.

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Tan, J.; Liu, Y.M.; Li, Y.Z.; You, F.F.; Zhang, M.Y.; Chen, Q.; Zou, K.; Sun, X. Diagnostic accuracy of optical coherence tomography for bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 298–304.

- Fernandez, M.I.; Brausi, M.; Clark, P.E.; Cookson, M.S.; Grossman, H.B.; Khochikar, M.; Kiemeney, L.A.; Malavaud, B.; Sanchez-Salas, R.; Soloway, M.S.; et al. Epidemiology, prevention, screening, diagnosis, and evaluation: Update of the ICUD-SIU joint consultation on bladder cancer. World J. Urol. 2019, 37, 3–13.

- Li, H.; Cao, Y.; Ma, P.; Ma, Z.; Li, C.; Yang, W.; Zhou, L. Novel Visualization Methods Assisted Transurethral Resection for Bladder Cancer: An Updated Survival-Based Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 644341.

- Farling, K.B. Bladder cancer: Risk factors, diagnosis, and management. Nurse Pract. 2017, 42, 26–33.

- Kamat, A.M.; Hegarty, P.K.; Gee, J.R.; Clark, P.E.; Svatek, R.S.; Hegarty, N.; Shariat, S.F.; Xylinas, E.; Schmitz-Drager, B.J.; Lotan, Y.; et al. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: Screening, diagnosis, and molecular markers. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 4–15.

- Yoshida, S.; Takahara, T.; Kwee, T.C.; Waseda, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Fujii, Y. DWI as an Imaging Biomarker for Bladder Cancer. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 208, 1218–1228.

- Kimura, K.; Yoshida, S.; Tsuchiya, J.; Yamada, I.; Tanaka, H.; Yokoyama, M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Yoshimura, R.; Tateishi, U.; Fujii, Y. Usefulness of texture features of apparent diffusion coefficient maps in predicting chemoradiotherapy response in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 671–679.

- Cai, Q.; Wen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Ouyang, L.; Ling, J.; Qian, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H. Investigation of Synthetic Magnetic Resonance Imaging Applied in the Evaluation of the Tumor Grade of Bladder Cancer. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2021, 54, 1989–1997.

- Hammouda, K.; Khalifa, F.; Soliman, A.; Ghazal, M.; El-Ghar, M.A.; Badawy, M.A.; Darwish, H.E.; Khelifi, A.; El-Baz, A. A multiparametric MRI-based CAD system for accurate diagnosis of bladder cancer staging. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2021, 90, 101911.

- Ghanshyam, K.; Nachiket, V.; Govind, S.; Shivam, P.; Sahay, G.B.; Mohit, S.; Ashok, K. Validation of vesical imaging reporting and data system score for the diagnosis of muscle invasive bladder cancer: A prospective cross-sectional study. Asian J. Urol. 2021.

- Meng, X.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y.; Feng, C.; Hu, D.; Liu, Z.; Kamel, I.R.; Li, Z. Accuracy and Challenges in the Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System for Staging Bladder Cancer. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2022.

- Panebianco, V.; Narumi, Y.; Altun, E.; Bochner, B.H.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Hafeez, S.; Huddart, R.; Kennish, S.; Lerner, S.; Montironi, R.; et al. Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Bladder Cancer: Development of VI-RADS (Vesical Imaging-Reporting And Data System). Eur. Urol. 2018, 74, 294–306.

- Luo, C.; Huang, B.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, L. Use of Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System (VI-RADS) for detecting the muscle invasion of bladder cancer: A diagnostic meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 4606–4614.

- Ahn, H.; Hwang, S.I.; Lee, H.J.; Choe, G.; Oh, J.J.; Jeong, S.J.; Byun, S.S.; Kim, J.K. Quantitation of bladder cancer for the prediction of muscle layer invasion as a complement to the vesical imaging-reporting and data system. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 1656–1666.

- Wang, X.; Tu, N.; Sun, F.; Wen, Z.; Lan, X.; Lei, Y.; Cui, E.; Lin, F. Detecting Muscle Invasion of Bladder Cancer Using a Proposed Magnetic Resonance Imaging Strategy. J. Magn. Reson Imaging 2021, 54, 1212–1221.

- Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Dan, G.; Zhong, Z.; Karaman, M.M.; Li, Z.; Hu, D.; Zhou, X.J. Evaluation of a fractional-order calculus diffusion model and bi-parametric VI-RADS for staging and grading bladder urothelial carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 890–900.

- Diana, P.; Lughezzani, G.; Saita, A.; Uleri, A.; Frego, N.; Contieri, R.; Buffi, N.; Balzarini, L.; D’Orazio, F.; Piergiuseppe, C.; et al. Head-to-Head Comparison between High-Resolution Microultrasound Imaging and Multiparametric MRI in Detecting and Local Staging of Bladder Cancer: The BUS-MISS Protocol. Bladder Cancer 2022, 8, 119–127.

- Li, Q.; Tang, J.; He, E.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, B. Differentiation between high- and low-grade urothelial carcinomas using contrast enhanced ultrasound. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 70883–70889.

- Li, C.; Gu, Z.; Ni, P.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; Li, W.; Yao, X.; Chen, Y. The value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of bladder cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2021, 17, 1179–1185.

- Shkolyar, E.; Jia, X.; Chang, T.C.; Trivedi, D.; Mach, K.E.; Meng, M.Q.; Xing, L.; Liao, J.C. Augmented Bladder Tumor Detection Using Deep Learning. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 714–718.

- Ali, N.; Bolenz, C.; Todenhofer, T.; Stenzel, A.; Deetmar, P.; Kriegmair, M.; Knoll, T.; Porubsky, S.; Hartmann, A.; Popp, J.; et al. Deep learning-based classification of blue light cystoscopy imaging during transurethral resection of bladder tumors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11629.

- Borhani, S.; Borhani, R.; Kajdacsy-Balla, A. Artificial intelligence: A promising frontier in bladder cancer diagnosis and outcome prediction. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 171, 103601.

- Lin, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, L.; Han, P.; Zhang, P.; Wei, Q. Prospective evaluation of fluorescence in situ hybridization for diagnosing urothelial carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 3928–3934.

- Dimashkieh, H.; Wolff, D.J.; Smith, T.M.; Houser, P.M.; Nietert, P.J.; Yang, J. Evaluation of urovysion and cytology for bladder cancer detection: A study of 1835 paired urine samples with clinical and histologic correlation. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013, 121, 591–597.

- Faiena, I.; Rosser, C.J.; Chamie, K.; Furuya, H. Diagnostic biomarkers in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. World J. Urol. 2019, 37, 2009–2016.

- Oeyen, E.; Hoekx, L.; De Wachter, S.; Baldewijns, M.; Ameye, F.; Mertens, I. Bladder Cancer Diagnosis and Follow-Up: The Current Status and Possible Role of Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 821.

- Chan, K.M.; Gleadle, J.; Li, J.; Vasilev, K.; MacGregor, M. Shedding Light on Bladder Cancer Diagnosis in Urine. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 383.

- Kuang, L.I.; Song, W.J.; Qing, H.M.; Yan, S.; Song, F.L. CYFRA21-1 levels could be a biomarker for bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 3921–3931.

- Matuszczak, M.; Salagierski, M. Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential of Biomarkers CYFRA 21.1, ERCC1, p53, FGFR3 and TATI in Bladder Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3360.

- Huang, Y.L.; Chen, J.; Yan, W.; Zang, D.; Qin, Q.; Deng, A.M. Diagnostic accuracy of cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1) for bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 3137–3145.

- Lei, Q.; Zhao, L.; Ye, S.; Sun, Y.; Xie, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, F.; Wu, S. Rapid and quantitative detection of urinary Cyfra21-1 using fluorescent nanosphere-based immunochromatographic test strip for diagnosis and prognostic monitoring of bladder cancer. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 4266–4272.

- Lu, P.; Cui, J.; Chen, K.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Tao, J.; Han, Z.; Zhang, W.; Song, R.; Gu, M. Diagnostic accuracy of the UBC((R)) Rapid Test for bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 3770–3778.

- Meisl, C.J.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Einarsson, R.; Koch, S.; Hallmann, S.; Weiss, S.; Hemdan, T.; Malmstrom, P.U.; Styrke, J.; Sherif, A.; et al. Nomograms including the UBC((R)) Rapid test to detect primary bladder cancer based on a multicentre dataset. BJU Int. 2021.

- Liang, Z.; Xin, R.; Yu, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, C.; Liu, X. Diagnostic value of urinary survivin as a biomarker for bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies. World J. Urol. 2018, 36, 1373–1381.

- Myers-Irvin, J.M.; Landsittel, D.; Getzenberg, R.H. Use of the novel marker BLCA-1 for the detection of bladder cancer. J. Urol. 2005, 174, 64–68.

- Roupret, M.; Gontero, P.; McCracken, S.R.C.; Dudderidge, T.; Stockley, J.; Kennedy, A.; Rodriguez, O.; Sieverink, C.; Vanie, F.; Allasia, M.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of MCM5 for the Detection of Recurrence in Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Followup: A Blinded, Prospective Cohort, Multicenter European Study. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 685–690.

- Roupret, M.; Gontero, P.; McCracken, S.R.C.; Dudderidge, T.; Stockley, J.; Kennedy, A.; Rodriguez, O.; Sieverink, C.; Vanie, F.; Allasia, M.; et al. Reducing the Frequency of Follow-up Cystoscopy in Low-grade pTa Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Using the ADXBLADDER Biomarker. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022.

- Babu, S.; Mockler, D.C.; Roa-Pena, L.; Szygalowicz, A.; Kim, N.W.; Jahanfard, S.; Gholami, S.S.; Moffitt, R.; Fitzgerald, J.P.; Escobar-Hoyos, L.F.; et al. Keratin 17 is a sensitive and specific biomarker of urothelial neoplasia. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 717–724.

- Singer, G.; Ramakrishnan, V.M.; Rogel, U.; Schotzau, A.; Disteldorf, D.; Maletzki, P.; Adank, J.P.; Hofmann, M.; Niemann, T.; Stadlmann, S.; et al. The Role of New Technologies in the Diagnosis and Surveillance of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Carcinoma: A Prospective, Double-Blinded, Monocentric Study of the XPERT(c) Bladder Cancer Monitor and Narrow Band Imaging(c) Cystoscopy. Cancers 2022, 14, 618.

- Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Zigeuner, R.; Shariat, S.F.; van Rhijn, B.W.; Comperat, E.; Sylvester, R.J.; Kaasinen, E.; Bohle, A.; Palou Redorta, J.; et al. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: Update 2013. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 639–653.

- Sanchini, M.A.; Gunelli, R.; Nanni, O.; Bravaccini, S.; Fabbri, C.; Sermasi, A.; Bercovich, E.; Ravaioli, A.; Amadori, D.; Calistri, D. Relevance of urine telomerase in the diagnosis of bladder cancer. JAMA 2005, 294, 2052–2056.

- Zuiverloon, T.C.; van der Aa, M.N.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Lingsma, H.F.; Bangma, C.H.; Zwarthoff, E.C. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutation analysis on voided urine for surveillance of patients with low-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3011–3018.

- Van Rhijn, B.W.; van der Poel, H.G.; van der Kwast, T.H. Urine markers for bladder cancer surveillance: A systematic review. Eur. Urol. 2005, 47, 736–748.

- Lokeshwar, V.B.; Schroeder, G.L.; Selzer, M.G.; Hautmann, S.H.; Posey, J.T.; Duncan, R.C.; Watson, R.; Rose, L.; Markowitz, S.; Soloway, M.S. Bladder tumor markers for monitoring recurrence and screening comparison of hyaluronic acid-hyaluronidase and BTA-Stat tests. Cancer 2002, 95, 61–72.

- Huang, Y.; Wei, J.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cen, J.; Feng, Z.; Lu, J.; Liang, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, W. Prognostic value of AIB1 and EIF5A2 in intravesical recurrence after surgery for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 6997–7011.

- Zhou, B.F.; Wei, J.H.; Chen, Z.H.; Dong, P.; Lai, Y.R.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, H.M.; Lu, J.; Zhou, F.J.; Xie, D.; et al. Identification and validation of AIB1 and EIF5A2 for noninvasive detection of bladder cancer in urine samples. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41703–41714.

- Laukhtina, E.; Shim, S.R.; Mori, K.; D’Andrea, D.; Soria, F.; Rajwa, P.; Mostafaei, H.; Comperat, E.; Cimadamore, A.; Moschini, M.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Novel Urinary Biomarker Tests in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 4, 927–942.

- Pichler, R.; Fritz, J.; Tulchiner, G.; Klinglmair, G.; Soleiman, A.; Horninger, W.; Klocker, H.; Heidegger, I. Increased accuracy of a novel mRNA-based urine test for bladder cancer surveillance. BJU Int. 2018, 121, 29–37.

- Dobbs, R.W.; Abern, M.R. A novel bladder cancer urinary biomarker: Can it go where no marker has gone before? Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, S96–S97.

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Ruan, W.; Huang, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; et al. Urine DNA methylation assay enables early detection and recurrence monitoring for bladder cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6278–6289.

- Mancini, M.; Righetto, M.; Zumerle, S.; Montopoli, M.; Zattoni, F. The Bladder EpiCheck Test as a Non-Invasive Tool Based on the Identification of DNA Methylation in Bladder Cancer Cells in the Urine: A Review of Published Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6542.

- Pierconti, F.; Martini, M.; Cenci, T.; Fiorentino, V.; Gianfrancesco, L.D.; Ragonese, M.; Bientinesi, R.; Rossi, E.; Larocca, L.M.; Racioppi, M.; et al. The bladder epicheck test and cytology in the follow-up of patients with non-muscle-invasive high grade bladder carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 40, 108.e119–108.e125.

- Cochetti, G.; Rossi de Vermandois, J.A.; Maula, V.; Cari, L.; Cagnani, R.; Suvieri, C.; Balducci, P.M.; Paladini, A.; Del Zingaro, M.; Nocentini, G.; et al. Diagnostic performance of the Bladder EpiCheck methylation test and photodynamic diagnosis-guided cystoscopy in the surveillance of high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A single centre, prospective, blinded clinical trial. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 40, 105.e111–105.e118.

- Feber, A.; Dhami, P.; Dong, L.; de Winter, P.; Tan, W.S.; Martinez-Fernandez, M.; Paul, D.S.; Hynes-Allen, A.; Rezaee, S.; Gurung, P.; et al. UroMark-a urinary biomarker assay for the detection of bladder cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 8.

- Piatti, P.; Chew, Y.C.; Suwoto, M.; Yamada, T.; Jara, B.; Jia, X.Y.; Guo, W.; Ghodoussipour, S.; Daneshmand, S.; Ahmadi, H.; et al. Clinical evaluation of Bladder CARE, a new epigenetic test for bladder cancer detection in urine samples. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 84.

- Steinbach, D.; Kaufmann, M.; Hippe, J.; Gajda, M.; Grimm, M.O. High Detection Rate for Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer Using an Approved DNA Methylation Signature Test. Clin. Genitourin Cancer 2020, 18, 210–221.

- Erdbrugger, U.; Blijdorp, C.J.; Bijnsdorp, I.V.; Borras, F.E.; Burger, D.; Bussolati, B.; Byrd, J.B.; Clayton, A.; Dear, J.W.; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; et al. Urinary extracellular vesicles: A position paper by the Urine Task Force of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12093.

- Liang, L.G.; Kong, M.Q.; Zhou, S.; Sheng, Y.F.; Wang, P.; Yu, T.; Inci, F.; Kuo, W.P.; Li, L.J.; Demirci, U.; et al. An integrated double-filtration microfluidic device for isolation, enrichment and quantification of urinary extracellular vesicles for detection of bladder cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46224.

- Miyake, M.; Nakai, Y.; Nishimura, N.; Ohnishi, S.; Oda, Y.; Fujii, T.; Owari, T.; Hori, S.; Morizawa, Y.; Gotoh, D.; et al. Hexylaminolevulinate-mediated fluorescent urine cytology with a novel automated detection technology for screening and surveillance of bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2021, 128, 244–253.

- Liu, Y.R.; Ortiz-Bonilla, C.J.; Lee, Y.F. Extracellular Vesicles in Bladder Cancer: Biomarkers and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2822.

- Georgantzoglou, N.; Pergaris, A.; Masaoutis, C.; Theocharis, S. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers Carriers in Bladder Cancer: Diagnosis, Surveillance, and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2744.

- Crocetto, F.; Barone, B.; Ferro, M.; Busetto, G.M.; La Civita, E.; Buonerba, C.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Terracciano, D.; Schalken, J.A. Liquid biopsy in bladder cancer: State of the art and future perspectives. Crit Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 170, 103577.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

756

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

25 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No