You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jen Sern Tham | -- | 2979 | 2022-07-21 10:27:01 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 2979 | 2022-07-22 03:43:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Zhang, H.(.; Tham, J.S.; Waheed, M. Information Overload during the COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25379 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

Zhang H(, Tham JS, Waheed M. Information Overload during the COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25379. Accessed December 26, 2025.

Zhang, Hongjie (Thomas), Jen Sern Tham, Moniza Waheed. "Information Overload during the COVID-19" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25379 (accessed December 26, 2025).

Zhang, H.(., Tham, J.S., & Waheed, M. (2022, July 21). Information Overload during the COVID-19. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25379

Zhang, Hongjie (Thomas), et al. "Information Overload during the COVID-19." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

Research has revealed that people whose primary source of COVID-19 information was social media experienced information overload (IO), which subsequently impacted their information behaviors. By definition, IO is “a physical and psychological distress that from human’s physical adaptive systems and decision-making process”.

health information overload

Cognitive Mediation Model

information engagement

information processing

COVID-19

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all areas of our lives in the past two years. Many countries had to lockdown or implemented drastic control measures to reverse the COVID-19 pandemic in the communities and keep it at bay. When the public situates in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, social media platforms have become the dominant avenue for most of them to access different types of COVID-19 information and remain connected with their social networks [1][2][3][4][5]. Individuals rely on various social media platforms to access daily COVID-19 case updates, understand vaccination-related knowledge and health policies, follow the latest preventive measures announced by the authorities, and communicate with family members or friends who are unable to meet physically due to restrictions on traveling and gathering. Apart from the widely acknowledged popularity and contributions of social media, the development of social media can create new problems. For example, social media made it challenging for public health authorities to manage the pandemic and design health messaging to promote preventive strategies among the public [3]. At this time, various types of COVID-19 mis/dis/mal-information are freely spreading on various social media platforms without censorship, including various conspiracy theories about the virus and vaccination, misleading information about how to treat COVID-19 infections, and scientifically incorrect messages on preventive measures. As the social media platforms offer a mixture of endorsed health information and conflicting information to the public every day, the World Health Organization (WHO) has indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic is accompanied by a true social media infodemic [6].

During this trying time, truth and rumors about the virus continue to spread on social media, causing its users to feel uncertain, confused, fatigued, and overloaded with COVID-19 health information [4]. It is not an overstatement that social media has opened up for rich health information acquisition, unprecedented in the history of the public health crisis that combines technology and social media to keep the public informed [7]. Contrary to conventional media in which the information tends to be selected by the gatekeepers and serves the local community [8], during the infodemic, social media presents myriad types of health information about COVID-19 to anyone and anywhere. This is detrimental to individuals’ health outcomes if they engage in ineffective and incorrect remedies or recommendations. In response, social media users operate within a complex information environment, featuring a wealth of ill-founded information that can overwhelm them and leave them experiencing different negative feelings [9]. These feelings reduce the effectiveness of cognition and can lead to following poorly sourced recommended behavior [10].

Recent research has revealed that people whose primary source of COVID-19 information was social media experienced information overload (IO) [11], which subsequently impacted their information behaviors [12]. By definition, IO is “a physical and psychological distress that from human’s physical adaptive systems and decision-making process” (p. 326) [13]. It occurs when someone is unable to process all inputs from media engagements and then this causes ineffective learning or terminates his or her information processing [14]. In public health domains, health IO (HIO) refers to the situation where individuals fail to sensibly handle the amount of information relating to health issues during a given time frame [15]. HIO is more likely to occur when individuals encounter health information about an urgent or a public-concerned health issue, such as public health emergencies [16] and non-communicable diseases [17]. It is particularly true in the context of the COVID-19 infodemic. Individuals are inundated with a flood of information during daily media engagements; hence, the chance of suffering from IO is very likely increased, which can thus be recognized as a severe negative side effect. Therefore, it is essential to thoroughly understand the negative effects of social media use on individuals’ health information management during the infodemic period.

2. Theoretical Foundation

IO has received significant scholarly attention because it is associated with health decision making and knowledge acquisition [10][15]. IO occurs when the quantity of information input is higher than the individuals’ ability to process information [18]. When the amount of information exceeds the available processing capacity, an individual has difficulty understanding it and may neglect a large amount of information that is vital for making health decisions [14][19]. Social media is an information avenue that enables individuals to engage with the latest information on many topics [20], but it is crucial to expand the body of knowledge on how information acquisition through social media can lead to IO in an infodemic.

The Cognitive Mediation Model (CMM) depicts how individuals are motivated to process information and gain knowledge from different media engagements. CMM posits that different motivations prompt individuals to pay attention to media and actively process and elaborate on the news and information they receive, which in turn influences the growth of knowledge and comprehension [21][22][23][24][25]. The core tenet of CMM shows that researchers should not consider knowledge gain to establish a direct exposure–effect process but, instead, a mediated approach. In the CMM framework, motivation is not directly associated with knowledge acquisition; instead, it subsequently fosters information engagement and cognitive elaboration [22]. For example, recent CMM studies in health domains found that different motivators triggered individuals to engage with H1N1 pandemic and cancer information; this, in turn, influenced their cognitive processing, knowledge gain, and behavioral intention [22][23][24]. In terms of applicability in the digital media environment, CMM has also been introduced on social media and the Internet to examine the public’s knowledge acquisition of scientific and health topics [25][26]. The underpinning role of the CMM framework in explaining the process of different knowledge acquisition in digital contexts is similar to its role in conventional media channels [21].

Although CMM has been used to study political and health information processing in various populations, e.g., [21][22][23][24][25], there are several gaps in the literature, particularly in understanding individuals’ information processing mechanisms during public health crises. First, CMM brings to light the functioning of elaboration in information processing, a positive cognitive approach to making sense of newly encountered information [27]. Effective elaboration helps individuals build connections among new information, existing knowledge, and previous experience. These connections influence their later knowledge development. Ideally, greater information engagement will increase the likelihood of positive elaboration, contributing to a higher level of knowledge [28]. In the context of COVID-19, however, finding specific answers is essential: Will more information engagements still drive a higher likelihood of positive cognitive elaboration? Will information engagements be effective when individuals encounter conflicting COVID-19 health information?

Second, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Malaysia’s Ministry of Health has engaged with national media outlets and news agencies to swiftly convey targeted information regarding preventive measures to the public. However, this information obtained by the public has been heterogeneous. Aside from the credible information aired by official sources, the public also receives inauthentic information that triggers subreption and hatred, especially on social media. Diving into this complicated information environment, individuals’ cognitive processing ability may become interrupted or terminated, causing confusion, barriers, and uncertainties regarding the information [10]. Consequently, individuals become overwhelmed by too much information, limiting their ability to process it effectively [18]. Hence, it is reasonable to argue that when processing health information during an infodemic, the role of IO should not be neglected in CMM.

Third, a major similarity can be seen across several previous studies. Researchers assume that individuals already live in an environment featuring excess information on a specific topic [26][29][30]. Nonetheless, these studies fail to address the following: (1) how information processing causes IO, (2) the operationalization of IO in any information processing model, and (3) the predicted magnitude of IO due to information engagement.

Fourth, although previous studies have articulated the usefulness of CMM in explaining IO [8][24], they have failed to use the initial mechanisms of CMM, namely, the “motivation–attention–cognitive processing” approach for examining the consequence of information processing [18]. In other words, IO’s role in health information processing has yet to be identified.

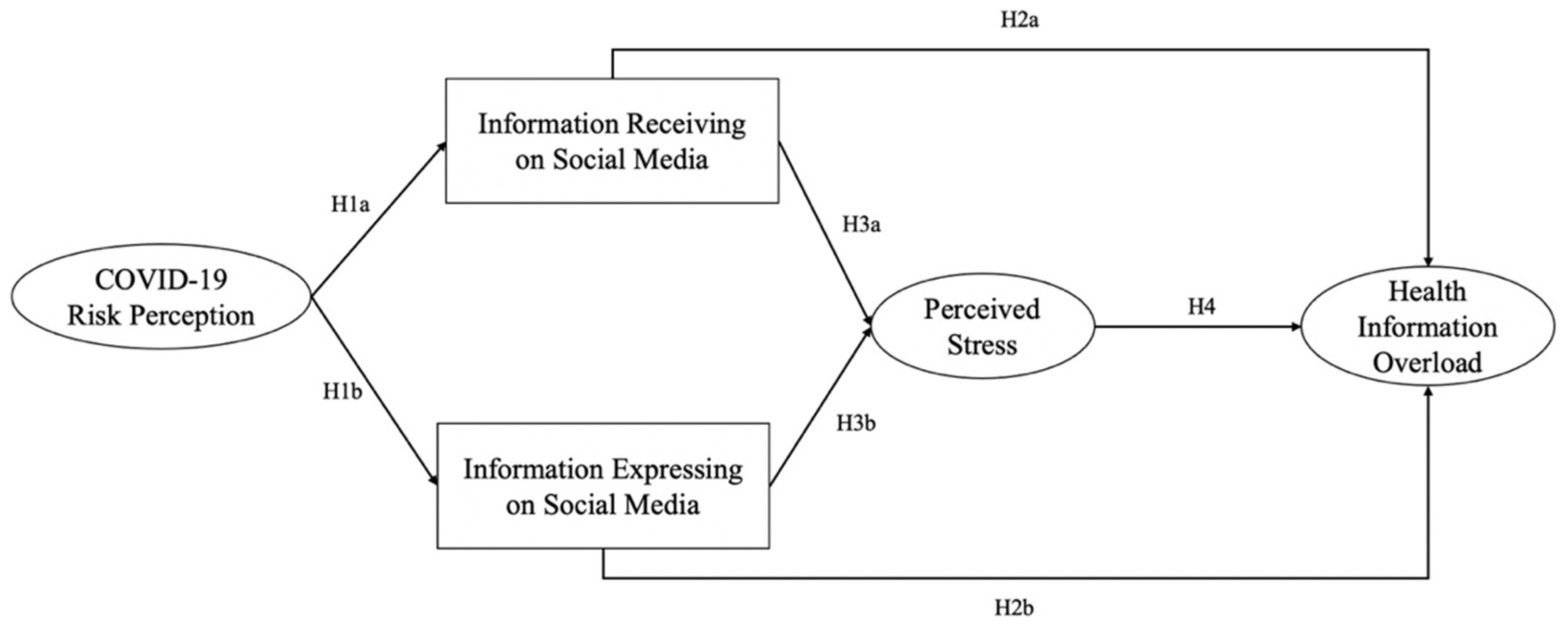

Taking these together, understanding IO based on the information processing paradigm, particularly CMM, is paramount for enhancing scholarly understanding of the negative consequences of information engagement on social media. In line with the prior CMM studies and the aforementioned questions, researchers aim to advance the CMM from three aspects. First, following prior CMM studies, researchers consider risk perception a key motivator for information engagement in the COVID-19 infodemic. Second, researchers argue that IO is associated with two types of information engagement on social media (receiving and expression). It clarifies the relationship in terms of how different information behaviors trigger IO. Third, echoing recent studies [31][32], researchers address one primary negative emotion during the COVID-19 pandemic: perceived stress, as a predictor of IO in health information processing. Thus, this current study extends CMM to health IO (HIO) by developing a conceptual HIO model in the context of the COVID-19 infodemic (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

3. Antecedent Motivator of Predicting Health Information Acquisition: Risk Perception

In public health emergencies, risk perception is one of the most important antecedents for predicting communicative and psychological actions [24][33]. However, the dimensions of risk perception during a pandemic are distinct from those in other health contexts, such as cancer and other health challenges [34][35]. Scholars have typically operationalized risk perception at the individual or personal level, emphasizing the cognitive and emotional dimensions [36][37][38]. Nevertheless, during the global COVID-19 pandemic, it has become inadequate to look only at how people conceive of a disease in terms of the risk to themselves (personal level risk perception). In fact, the entire population is at some degree of risk. Therefore, the risk perception regarding infectious health emergencies goes beyond personal to societal and global relevance [35][39][40]. Ample evidence of the relationship between different dimensions of risk perception and information engagement has been reported. For example, a comparative study found that Chinese college students perceived higher risk at the personal and societal levels than their American counterparts regarding the H1N1 pandemic, which was affected by their relevant media exposure and interpersonal discussion [39]. A recent study found that those who perceived higher risk at the individual and societal levels were more likely to seek information on the Zika virus, showing mobilized preventive intention; however, risk perception at the global level failed to demonstrate this relationship [35].

For the case of COVID-19, Dryhurst et al. [34] argued that researchers should consider risk perception not only in relation to well-established and model-driven constructs but also in terms of integrated logic from a range of schools, such as perceived likelihood, perceived seriousness, and temporal-spatial differences [41]. This approach extends the self–other risk difference dimension of Han et al. [39] and the three-level approach of Lee et al. [35] and provides a holistic way of measuring public risk perception during a pandemic. Previous studies on risk perception during the COVID-19 pandemic have paid little attention to different levels of risk perception (personal, societal, and global) or how these dimensions motivate people to engage on social media during a pandemic. However, this entry follows and adopts a conceptualization of public risk perception during a pandemic involving perceived seriousness and likelihood at the personal, societal, and global levels [34].

4. Linking Risk Perception, Social Media Engagement, and Health Information Overload

The proposition of CMM indicates that health information engagement is significantly stimulated by health motivation [22][23]. Recent studies have found that risk perception is a strong antecedent motivator for health-related media attention [23][24]. For example, Lee et al. [23] showed that risk perception positively predicted media attention and interpersonal communication concerning breast cancer among Singaporean women. Likewise, Zhang and Yang [24] also reported that risk perception positively predicted information seeking and scanning behaviors regarding breast cancer information in China.

With the growth of the use of social media, particularly during the infodemic, studies have identified the development tendency of CMM—from examining attention on different media channels [42] to understanding other information behaviors (e.g., seeking and scanning) [24]. On the one hand, information seeking is increasingly acknowledged as a purposeful activity for obtaining information from certain sources and as an activity that requires effort to obtain information outside the typical exposure pattern [43]. Information scanning, on the other hand, refers to the amount of attention paid to the media and is usually categorized as a passive information acquisition behavior [44]. In particular, scholars have noticed that it can be challenging to conceptualize information scanning [45][46]. During daily digital media usage, individuals may encounter news notifications through social media or online news applications that may not be the information they are seeking. The decision whether to follow notification and read a full-length article requires active cognitive effort. Hence, information scanning in the digital environment cannot be completely understood as unintentional or passive information exposure. Additionally, it entails a decision-making process that actively seeks out the information [47]. Yoo et al. [48] simplified the information seeking and scanning mechanism by highlighting communicative actions rather than identifying actions as active or passive to avoid the definitional conflict. Yoo et al. [48] explained that when social media is widely accessed, particularly during a crisis, users are more likely to be exposed to messages that may influence their perceptions and preventive behaviors related to crisis events. However, users not only receive messages but also express their thoughts to their social circles. Consequently, during public health emergencies, the public may play a crucial role in message expression through social media, for instance, by creating content, amplifying and commenting on traditional news articles [49]. For the MERS pandemic, Yoo et al. [48] documented that individuals who expressed more relevant information on social media had better self-efficacy than those who expressed less. Those who received more MERS information can be expected to have greater perceived threats and stronger preventive intentions. Another study found that people who used Facebook to express more information concerning dust pollution had a higher level of preventive intention [15]. By contrast, people who received more relevant details concerning dust pollution showed a greater intention to comply with government recommendations.

HIO was initially conceptualized in cancer risk communication [15]. There has been a noticeable shift in research focus, from creating instruments for a specific health concern to a thorough examination of the relationship between HIO and other health-related factors [26][50]. Scholars have been examining the effects of HIO since the commencement of earlier versions of the Health Information National Trend Survey (HINTS). A 2007 HINTS study found that sex, age, perceived health status, and socioeconomic status were all associated with CIO. That study also showed that people with no history of depression or only mild depression were more likely to feel overloaded [51]. Recently, a study found that individuals who experienced greater IO were reluctant to receive an annual medical check-up and were less knowledgeable about sun-safe behaviors [17].

In addition, several empirical studies have also been performed to understand the role of HIO in other health domains, including the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, researchers highlighted the association between media engagement and perceived HIO. For instance, a cross-national survey study found that individuals receiving information from mass media were more likely to experience high COVID-19 IO than those who received information via social media [52]. Another study in Finland also articulated that receiving COVID-19 information on social media caused the public to feel overwhelmed [53]. Therefore, it is crucial to clarify the underlying mechanism of HIO during the pandemic, particularly cause–effect relationships related to information behaviors. Instead of studying HIO as an external condition, a different approach is taken here, operationally defining it as the consequence of an amount of information exceeding the human information processing capacity [18].

5. Linking Social Media Engagement, Negative Emotion, and Health Information Overload

In infectious disease outbreaks, individuals living within a media environment are exposed to emotional content [32]. Such content could produce different responses in different individuals. Researchers have found that health information, especially information from online channels, is largely emotionally framed [32][54]. The number of confirmed disease cases or reporting of mounting death tolls is highlighted, along with the presentation of manipulated information and the spreading of misinformation. This information triggers cognitive uncertainty about the disease and negative self-relevant emotions, including fear, stress, and worry [55][56]. For instance, during the MERS outbreak, fear and anger were dominant negative emotions among the general public [57]. Another study also found that fear and anger triggered perceptions of personal risk regarding MERS, which in turn influenced preventive behaviors [32]. Yang et al. [58] documented that exposure to virus-related information in media could cause fear among female Americans.

Moreover, self-relevant emotions have been highlighted in health communication studies in relation to cancer. Chae [55] found that fear and worry were positively associated with cancer information use. Fear was also positively related to cancer information avoidance, whereas worry is negatively associated with avoidance. Scholars have also observed the effects of negative emotions and intentions and the use of preventive measures in COVID-19. For example, social media usage in Chinese populations may lead to significant worry concerning the outbreak, where worry is positively associated with preventive behaviors [59]. In Thailand, a study indicated that the longer the time spent on information engagement on social media, the greater the chance one might suffer from anxiety and fear [60].

Although COVID-19 studies usually focus on negative emotions, such as worry, fear, and anger [29][30], Lwin et al. [61] found that the percentage of fear-centered Twitter posts drastically decreased from approximately 60% at the end of January 2020 to less than 30% in early April 2020. The trend in angry Twitter posts was relatively stable within those 3 months. Therefore, as the world has been suffering from this pandemic for more than a year, it seems clear that stress, a long-term negative emotion, can become more arresting than worry or fear. Empirical studies have identified different roles of perceived stress. For example, one study found that social media usage and interpersonal communication about COVID-19 issues were positively associated with stress [62]. Another study showed that fatalism regarding COVID-19 is a strong and positive predictor of stress [31].

References

- Bento, A.I.; Nguyen, T.; Wing, C.; Lozano-Rojas, F.; Ahn, Y.Y.; Simon, K. Evidence from internet search data shows information-seeking responses to news of local COVID-19 cases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11220–11222.

- Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A. The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 355–357.

- Hernández-García, I.; Giménez-Júlvez, T. Assessment of health information about COVID-19 prevention on the internet: Infodemiological study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e18717.

- Kim, H.K.; Ahn, J.; Atkinson, L.; Kahlor, L.A. Effects of COVID-19 misinformation on information seeking, avoidance, and processing: A multicounty comparative study. Sci. Commun. 2020, 42, 586–615.

- Mohamad, E.; Tham, J.S.; Ayub, S.H.; Hamzah, M.R.; Hashim, H.; Azlan, A.A. Relationship between COVID-19 information sources and attitudes in battling the pandemic among the Malaysian public: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23922.

- Hao, K.; Basu, T. The Coronavirus Is the First True Social Media Infodemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/615184/the-coronavirus-is-the-first-true-social-media-infodemic/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Manganello, J.; Bleakley, A.; Schumacher, P. Pandemics and PSAs: Rapidly changing information in a new media landscape. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 1711–1714.

- Melki, J.; Tamim, H.; Hadid, D.; Farhat, S.; Makki, M.; Ghandour, L.; Hitti, E. Media exposure and health behavior during pandemics: The mediating effect of perceived knowledge and fear on compliance with COVID-19 prevention measures. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 586–596.

- Rathore, F.A.; Farooq, F. Information overload and infodemic in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2020, 7, S162–S165.

- Chae, J.; Lee, C.J.; Jensen, J.D. Correlates of cancer information overload: Focusing on individual ability and motivation. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 626–634.

- Farooq, A.; Laato, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N. Impact of online information on self-isolation intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19128.

- Swar, B.; Hameed, T.; Reychav, I. Information overload, psychological ill-being, and behavioral intention to continue online healthcare information search. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 416–425.

- Toffler, A. Future Shock; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970.

- Beaudoin, C.E. Explaining the relationship between internet use and interpersonal trust: Taking into account motivation and information overload. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2008, 13, 550–568.

- Jensen, J.D.; Carcioppolo, N.; King, A.J.; Scherr, C.L.; Jones, C.L.; Niederdieppe, J. The cancer information overload (CIO) scale: Establishing predictive and discriminant validity. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 90–96.

- Hong, H.; Kim, H.J. Antecedents and Consequences of Information Overload in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9305.

- Jensen, J.D.; Pokharel, M.; Carcioppolo, N.; Upshaw, S.; John, K.K.; Katz, R.A. Cancer information overload: Discriminant validity and relationship to sun safe behaviors. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 309–314.

- Schmitt, J.B.; Debbelt, C.A.; Schneider, F.M. Too much information? Predictors of information overload in the context of online news exposure. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 1151–1167.

- Eppler, M.J.; Mengis, J. The concept of information overload—A review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, mis, and related disciplines. Inf. Soc. 2004, 20, 325–344.

- Yoo, W. How risk communication via Facebook and Twitter shapes behavioral intentions: The case of fine dust pollution in South Korea. J. Health Commun. 2019, 24, 663–673.

- Eveland, W.P. The cognitive mediation model of learning from the news: Evidence from nonelection, off-year election, and presidential election contexts. Commun. Res. 2001, 28, 571–601.

- Ho, S.S.; Peh, X.; Soh, V.W. The cognitive mediation model: Factors influencing public knowledge of the H1N1 pandemic and intention to take precautionary behaviors. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 773–794.

- Lee, E.W.; Shin, M.; Kawaja, A.; Ho, S.S. The augmented cognitive mediation model: Examining antecedents of factual and structural breast cancer knowledge among Singaporean women. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 583–592.

- Zhang, L.; Yang, X. Linking risk perception to breast cancer examination intention in China: Examining an adapted cognitive mediation model. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1813–1824.

- Ho, S.S.; Yang, X.; Thanwarani, A.; Chan, J.M. Examining public acquisition of science knowledge from social media in Singapore: An extension of the cognitive mediation model. Asian J. Commun. 2017, 27, 193–212.

- Jiang, S.; Beaudoin, C.E. Health literacy and the internet: An exploratory study on the 2013 HINTS survey. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 240–248.

- Eveland, W.P., Jr.; Marton, K.; Seo, M. Moving beyond “just the facts” the influence of online news on the content and structure of public affairs knowledge. Commun. Res. 2004, 31, 82–108.

- Eveland, W.P., Jr.; Dunwoody, S. An investigation of elaboration and selective scanning as mediators of learning from the Web versus print. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2002, 46, 34–53.

- Gardikiotis, A.; Malinaki, E.; Charisiadis-Tsitlakidis, C.; Protonotariou, A.; Archontis, S.; Lampropoulou, A.; Maraki, I.; Papatheodorou, K.; Zafeiriou, G. Emotional and cognitive responses to COVID-19 information overload under lockdown predict media attention and risk perceptions of COVID-19. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 434–442.

- Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Yoganathan, V.; Osburg, V.S. COVID-19 information overload and generation Z’s social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120600.

- Ngien, A.; Jiang, S. The effect of social media on stress among young adults during COVID-19 pandemic: Taking into account fatalism and social media exhaustion. Health Commun. 2021. advanced online publication.

- Oh, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, C. The effects of social media use on preventive behaviors during infectious disease outbreaks: The mediating role of self-relevant emotions and public risk perception. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 972–981.

- Choi, D.H.; Yoo, W.; Noh, G.Y.; Park, K. The impact of social media on risk perceptions during the MERS outbreak in South Korea. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 422–431.

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; Van Der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; Van Der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006.

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.W.; Chock, T.M. From risk butterflies to citizens engaged in risk prevention in the Zika virus crisis: Focusing on personal, societal and global risk perceptions. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 671–680.

- Dohle, S.; Keller, C.; Siegrist, M. Examining the relationship between affect and implicit associations: Implications for risk perception. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1116–1128.

- Dunwoody, S.; Neuwirth, K. Coming to terms with the impact of communication on scientific and technological risk judgments. In Risky Business: Communicating Issues of Science, Risk and Public Policy; Wilkins, L., Patterson, P., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1991; pp. 11–30.

- Freimuth, V.S.; Hovick, S.R. Cognitive and emotional health risk perceptions among people living in poverty. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 303–318.

- Han, G.K.; Zhang, J.M.; Chu, K.R.; Shen, G. Self-other differences in H1N1 flu risk perception in a global context: A comparative study between the United States and China. Health Commun. 2014, 29, 109–123.

- Oh, S.; Paek, H.J.; Hove, T. Cognitive and emotional dimensions of perceived risk characteristics, genre-specific media effects, and risk perceptions: The case of H1N1 influenza in South Korea. Asian J. Commun. 2015, 25, 14–32.

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 45–72.

- Yang, X.; Chuah, A.S.; Lee, E.W.; Ho, S.S. Extending the cognitive mediation model: Examining factors associated with perceived familiarity and factual knowledge of nanotechnology. Mass Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 403–426.

- Jiang, S.; Wang, P.; Liu, L.P.; Ngien, A.; Wu, X. Social media communication about HPV vaccine in China: A study using topic modeling and survey. Health Commun. 2021. advanced online publication.

- Shim, M.; Cappella, J.N.; Han, J.Y. How does insightful and emotional disclosure bring potential health benefits? Study based on online support groups for women with breast cancer. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 432–454.

- Hornik, R.; Parvanta, S.; Mello, S.; Freres, D.; Kelly, B.; Schwartz, J.S. Effects of scanning (routine health information exposure) on cancer screening and prevention behaviors in the general population. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 1422–1435.

- Tandoc, E.C., Jr.; Lee, J.C.B. When viruses and misinformation spread: How young Singaporeans navigated uncertainty in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. New Media Soc. 2020. advanced online publication.

- Lewis, N. Information seeking and scanning. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects; Rössler, P., Hoffner, C.A., Zoonen, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–10.

- Yoo, W.; Choi, D.H.; Park, K. The effects of SNS communication: How expressing and receiving information predict MERS-preventive behavioral intentions in South Korea. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 34–43.

- Chew, C.; Eysenbach, G. Pandemics in the age of Twitter: Content analysis of tweets during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14118.

- Chae, J.; Lee, C.J.; Kim, K. Prevalence, predictors, and psychosocial mechanism of cancer information avoidance: Findings from a national survey of US adults. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 322–330.

- Kim, K.; Lustria, M.L.A.; Burke, D.; Kwon, N. Predictors of cancer information overload: Findings from a national survey. Inf. Res. 2007, 12, 12–14.

- Mohammed, M.; Sha’aban, A.; Jatau, A.I.; Yunusa, I.; Isa, A.M.; Wada, A.S.; Obamiro, K.; Zainal, H.; Ibrahim, B. Assessment of COVID-19 information overload among the general public. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021. advanced online publication.

- Soroya, S.H.; Farooq, A.; Mahmood, K.; Isoaho, J.; Zara, S.E. From information seeking to information avoidance: Understanding the health information behavior during a global health crisis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102440.

- Ofoghi, B.; Mann, M.; Verspoor, K. Towards early discovery of salient health threats: A social media emotion classification technique. Proc. Pac. Symp. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2016, 21, 504–515.

- Chae, J. Online cancer information seeking increases cancer worry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 144–150.

- Tugtekin, U.; Barut Tugtekin, E.; Kurt, A.A.; Demir, K. Associations between fear of missing out, problematic smartphone sse, and social networking services fatigue among young adults. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120963760.

- Song, J.; Song, T.M.; Seo, D.C.; Jin, D.L.; Kim, J.S. Social big data analysis of information spread and perceived infection risk during the 2015 Middle Ease respiratory syndrome outbreak in South Korea. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 22–29.

- Yang, C.; Dillard, J.P.; Li, R. Understanding fear of Zika: Personal, interpersonal, and media influences. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 2535–2545.

- Liu, P.L. COVID-19 information seeking on digital media and preventive behaviors: The mediation role of worry. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 677–682.

- Mongkhon, P.; Ruengorn, C.; Awiphan, R.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Nochaiwong, S. Exposure to COVID-19-Related information and its association with mental health problems in Thailand: Nationwide, cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25363.

- Lwin, M.O.; Lu, J.; Sheldenkar, A.; Schulz, P.J.; Shin, W.; Gupta, R.; Yang, Y. Global sentiments surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic on Twitter: Analysis of Twitter trends. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19447.

- First, J.M.; Shin, H.; Ranjit, Y.S.; Houston, J.B. COVID-19 Stress and depression: Examining social media, traditional media, and interpersonal communication. J. Loss Trauma 2021, 26, 101–115.

More

Information

Subjects:

Information Science & Library Science

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No