| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Izadora Souza | -- | 5953 | 2022-07-07 14:27:57 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | -490 word(s) | 5463 | 2022-07-08 03:09:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

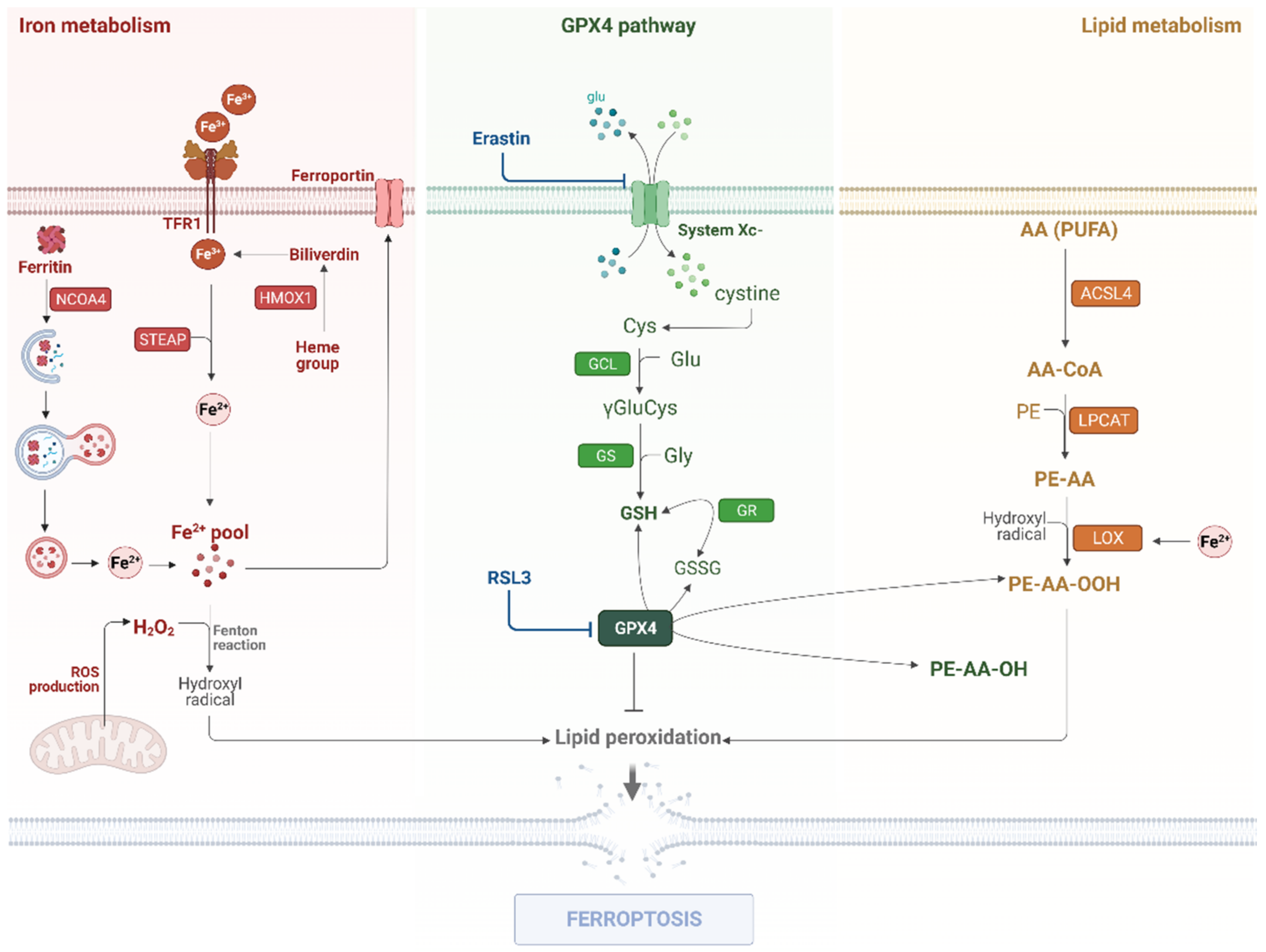

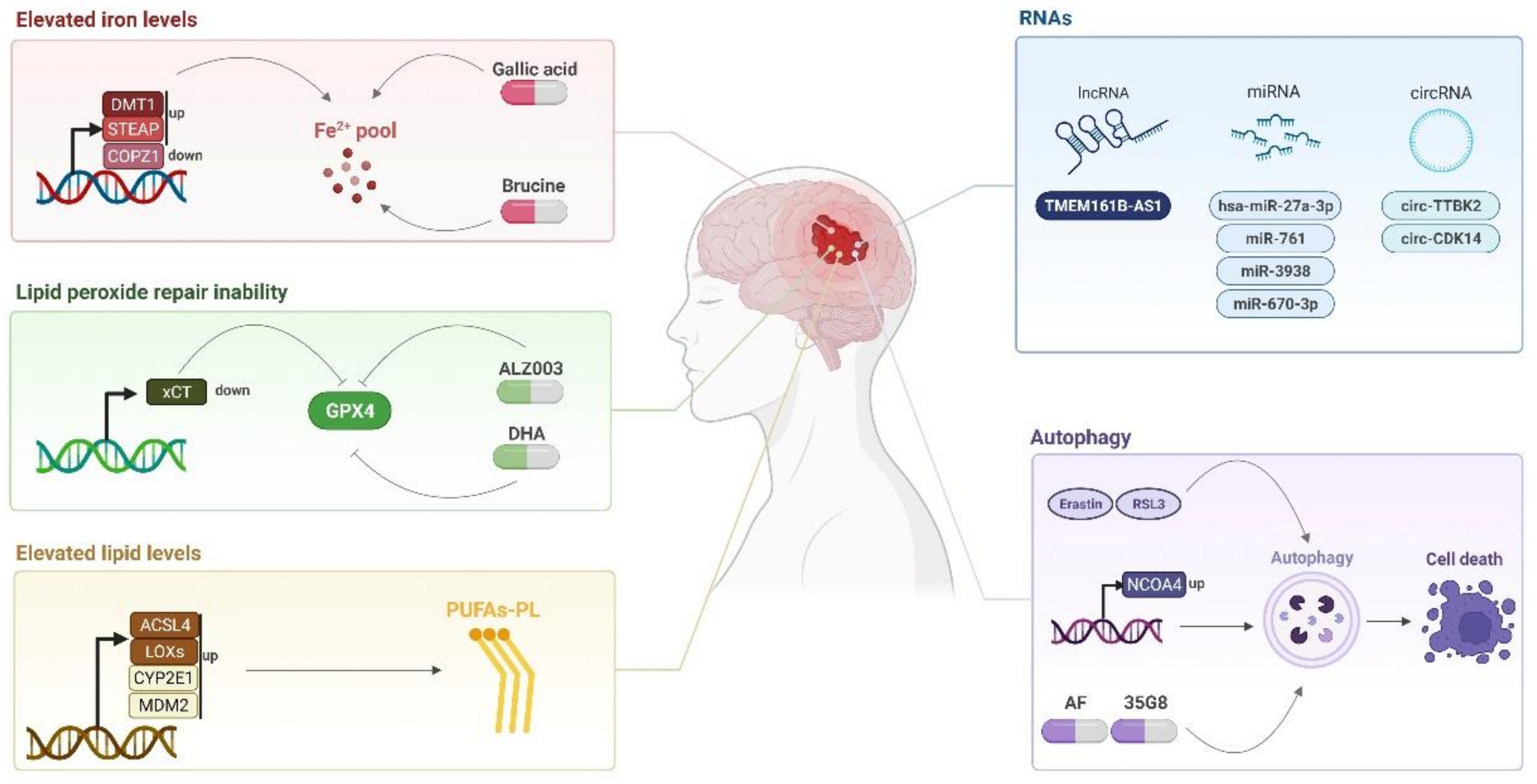

Glioblastoma multiforme is a lethal disease and represents the most common and severe type of glioma. Drug resistance and the evasion of cell death are the main characteristics of its malignancy, leading to a high percentage of disease recurrence and the patients’ low survival rate. Exploiting the modulation of cell death mechanisms could be an important strategy to prevent tumor development and reverse the high mortality and morbidity rates in glioblastoma patients. Ferroptosis is a recently described type of cell death, which is characterized by iron accumulation, high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA)-containing phospholipids, and deficiency in lipid peroxidation repair. Several studies have demonstrated that ferroptosis has a potential role in cancer treatment and could be a promising approach for glioblastoma patients.

1. Introduction

2. Ferroptosis Modulation on Glioma

2.1. Iron Metabolism

2.2. Lipid Metabolism

2.3. The GPX4 Pathway

3. Non-Canonical Pathways

3.1. LncRNAs, CircRNAs, and miRNAs

3.2. Autophagy

4. Targeting Ferroptosis for Glioblastoma Treatment and Prognosis

4.1. Ferroptosis-Inducing Compounds

Compounds capable of inducing ferroptosis can direct new treatments for glioblastoma such as brucine and cRGD/Pt + DOX@GFNPs nanoformulation, which promotes ferroptosis mediated by the iron pathway [20][21] as well as AF and 35G8, which induced ferroptosis in an autophagy dependent manner [50][68], above-as mentioned.4.2. Potential Biomarkers

References

- Davis, M. Glioblastoma: Overview of Disease and Treatment. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 20, S2–S8.

- Venur, V.A.; Peereboom, D.M.; Ahluwalia, M.S. Current medical treatment of glioblastoma. Cancer Treat. Res. 2015, 163, 103–115.

- Singh, N.; Miner, A.; Hennis, L.; Mittal, S. Mechanisms of temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma—A comprehensive review. Cancer Drug Resist. 2020, 4, 17–43.

- Woo, P.; Li, Y.; Chan, A.; Ng, S.; Loong, H.; Chan, D.; Wong, G.; Poon, W.-S. A multifaceted review of temozolomide resistance mechanisms in glioblastoma beyond O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. Glioma 2019, 2, 68–82.

- Galluzzi, L.; Pedro, J.M.B.-S.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. Regulated cell death and adaptive stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2405–2410.

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 486–541.

- Liang, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Dong, X. Recent Progress in Ferroptosis Inducers for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1904197.

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072.

- Vogt, A.-C.S.; Arsiwala, T.; Mohsen, M.; Vogel, M.; Manolova, V.; Bachmann, M.F. On Iron Metabolism and Its Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4591.

- Mancias, J.D.; Wang, X.; Gygi, S.P.; Harper, J.W.; Kimmelman, A.C. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature 2014, 509, 105–109.

- Lei, P.; Bai, T.; Sun, Y. Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Relations With Regulated Cell Death: A Review. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 139.

- Dixon, S.J.; Stockwell, B.R. The Hallmarks of Ferroptosis. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2019, 3, 35–54.

- Torti, S.V.; Manz, D.H.; Paul, B.T.; Blanchette-Farra, N.; Torti, F.M. Iron and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 38, 97–125.

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, K.-N.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, F.; Chai, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; et al. Ferronostics: Measuring Tumoral Ferrous Iron with PET to Predict Sensitivity to Iron-Targeted Cancer Therapies. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 949–955.

- Song, Q.; Peng, S.; Sun, Z.; Heng, X.; Zhu, X. Temozolomide Drives Ferroptosis via a DMT1-Dependent Pathway in Glioblastoma Cells. Yonsei Med. J. 2021, 62, 843.

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ni, S.; Wikerholmen, T.; Xi, K.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, B.; et al. Loss of COPZ1 induces NCOA4 mediated autophagy and ferroptosis in glioblastoma cell lines. Oncogene 2021, 40, 1425–1439.

- Chen, H.; Xu, C.; Yu, Q.; Zhong, C.; Peng, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, G. Comprehensive landscape of STEAP family functions and prognostic prediction value in glioblastoma. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 2988–3000.

- Ohgami, R.S.; Campagna, D.R.; McDonald, A.; Fleming, M.D. The Steap proteins are metalloreductases. Blood 2006, 108, 1388–1394.

- Stockwell, B.R.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascón, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285.

- Zhang, Y.; Xi, K.; Fu, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, D.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, B.; et al. Versatile metal-phenolic network nanoparticles for multitargeted combination therapy and magnetic resonance tracing in glioblastoma. Biomaterials 2021, 278, 121163.

- Lu, S.; Wang, X.-Z.; He, C.; Wang, L.; Liang, S.-P.; Wang, C.-C.; Li, C.; Luo, T.-F.; Feng, C.-S.; Wang, Z.-C.; et al. ATF3 contributes to brucine-triggered glioma cell ferroptosis via promotion of hydrogen peroxide and iron. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 1690–1702.

- Gaschler, M.M.; Stockwell, B.R. Lipid peroxidation in cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 419–425.

- Dixon, S.J.; Winter, G.E.; Musavi, L.S.; Lee, E.D.; Snijder, B.; Rebsamen, M.; Superti-Furga, G.; Stockwell, B.R. Human Haploid Cell Genetics Reveals Roles for Lipid Metabolism Genes in Nonapoptotic Cell Death. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1604–1609.

- Sparvero, L.J. PEBP1 Wardens Ferroptosis by Enabling Lipoxygenase Generation of Lipid Death Signals. Cell 2017, 171, 628–641.e26.

- Doll, S.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Panzilius, E.; Kobayashi, S.; Ingold, I.; Irmler, M.; Beckers, J.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 91–98.

- Kagan, V.E.; Mao, G.; Qu, F.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Doll, S.; Croix, C.S.; Dar, H.H.; Liu, B.; Tyurin, V.A.; Ritov, V.B.; et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 81–90.

- Bao, C.; Zhang, J.; Xian, S.Y.; Chen, F. MicroRNA-670-3p suppresses ferroptosis of human glioblastoma cells through targeting. Free Radic. Res. 2021, 55, 853–864.

- Cheng, J.; Fan, Y.Q.; Liu, B.H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.M.; Chen, Q.X. ACSL4 suppresses glioma cells proliferation via activating ferroptosis. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 43, 147–158.

- Yang, W.S.; Kim, K.J.; Gaschler, M.M.; Patel, M.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4966–E4975.

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Cheng, K.K.-Y.; Xu, H.; Li, Q.; Hua, T.; Jiang, X.; Sheng, L.; Mao, J.; et al. miR-18a promotes glioblastoma development by down-regulating ALOXE3-mediated ferroptotic and anti-migration activities. Oncogenesis 2021, 10, 15.

- Ye, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Hu, P.; Tong, S.A.; Liu, Z.; Tian, D. Downregulation of CYP2E1 is associated with poor prognosis and tumor progression of gliomas. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 8100–8113.

- Venkatesh, D.; O’Brien, N.A.; Zandkarimi, F.; Tong, D.R.; Stokes, M.E.; Dunn, D.E.; Kengmana, E.S.; Aron, A.T.; Klein, A.M.; Csuka, J.M.; et al. MDM2 and MDMX promote ferroptosis by PPARα-mediated lipid remodeling. Genes Dev. 2020, 34, 526–543.

- Forcina, G.C.; Dixon, S.J. GPX4 at the Crossroads of Lipid Homeostasis and Ferroptosis. Proteomics 2019, 19, e1800311.

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Glutathione depletion induces ferroptosis, autophagy, and premature cell senescence in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–15.

- Seelig, G.F.; Simondsen, R.P.; Meister, A. Reversible dissociation of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase into two subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 9345–9347.

- Ikawa, T.; Sato, M.; Oh-hashi, K.; Furuta, K.; Hirata, Y. Oxindole–curcumin hybrid compound enhances the transcription of γ-glutamylcysteine ligase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 896, 173898.

- Jiang, T.; Chu, J.; Chen, H.; Cheng, H.; Su, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Tian, S.; Li, Q. Gastrodin Inhibits H2O2-Induced Ferroptosis through Its Antioxidative Effect in Rat Glioma Cell Line C6. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 43, 480–487.

- Wei, R.; Qiu, H.; Xu, J.; Mo, J.; Liu, Y.; Gui, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, S.; Yao, H.; Huang, X.; et al. Expression and prognostic potential of GPX1 in human cancers based on data mining. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 124.

- Tan, S.; Hou, X.; Mei, L. Dihydrotanshinone I inhibits human glioma cell proliferation via the activation of ferroptosis. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 122.

- Wang, X.; Lu, S.; He, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Piao, M.; Chi, G.; Luo, Y.; Ge, P. RSL3 induced autophagic death in glioma cells via causing glycolysis dysfunction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 518, 590–597.

- Fan, Z.; Wirth, A.-K.; Chen, D.; Wruck, C.J.; Rauh, M.; Buchfelder, M.; Savaskan, N. Nrf2-Keap1 pathway promotes cell proliferation and diminishes ferroptosis. Oncogenesis 2017, 6, e371.

- Koppula, P.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: Ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 599–620.

- Sato, H.; Tamba, M.; Ishii, T.; Bannai, S. Cloning and Expression of a Plasma Membrane Cystine/Glutamate Exchange Transporter Composed of Two Distinct Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 11455–11458.

- Umans, R.A.; Martin, J.; Harrigan, M.E.; Patel, D.C.; Chaunsali, L.; Roshandel, A.; Iyer, K.; Powell, M.D.; Oestreich, K.; Sontheimer, H. Transcriptional Regulation of Amino Acid Transport in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Cancers 2021, 13, 6169.

- Chen, L.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Yu, B.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y. Erastin sensitizes glioblastoma cells to temozolomide by restraining xCT and cystathionine-γ-lyase function. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1465–1474.

- Sugiyama, A.; Ohta, T.; Obata, M.; Takahashi, K.; Seino, M.; Nagase, S. xCT inhibitor sulfasalazine depletes paclitaxel-resistant tumor cells through ferroptosis in uterine serous carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 2689–2700.

- Dixon, S.J.; Patel, D.N.; Welsch, M.; Skouta, R.; Lee, E.D.; Hayano, M.; Thomas, A.G.; Gleason, C.E.; Tatonetti, N.P.; Slusher, B.S.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine–glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife 2014, 3, e02523.

- Feng, H.; Stockwell, B.R. Unsolved mysteries: How does lipid peroxidation cause ferroptosis? PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006203.

- Buccarelli, M.; Marconi, M.; Pacioni, S.; De Pasqualis, I.; D’Alessandris, Q.G.; Martini, M.; Ascione, B.; Malorni, W.; Larocca, L.M.; Pallini, R.; et al. Inhibition of autophagy increases susceptibility of glioblastoma stem cells to temozolomide by igniting ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 841.

- Kyani, A.; Tamura, S.; Yang, S.; Shergalis, A.; Samanta, S.; Kuang, Y.; Ljungman, M.; Neamati, N. Discovery and Mechanistic Elucidation of a Class of Protein Disulfide Isomerase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 177.

- Chen, D.; Fan, Z.; Rauh, M.; Buchfelder, M.; Eyupoglu, I.Y.; Savaskan, N. ATF4 promotes angiogenesis and neuronal cell death and confers ferroptosis in a xCT-dependent manner. Oncogene 2017, 36, 5593–5608.

- Chen, D.; Rauh, M.; Buchfelder, M.; Eyupoglu, I.Y.; Savaskan, N. The oxido-metabolic driver ATF4 enhances temozolamide chemo-resistance in human gliomas. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 51164–51176.

- Hayashima, K.; Kimura, I.; Katoh, H. Role of ferritinophagy in cystine deprivation-induced cell death in glioblastoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 539, 56–63.

- Dodson, M.; Castro-Portuguez, R.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2019, 23, 101107.

- Rocha, C.R.R.; Rocha, A.R.; Silva, M.M.; Gomes, L.R.; Latancia, M.T.; Andrade-Tomaz, M.; De Souza, I.; Monteiro, L.K.S.; Menck, C.F.M. Revealing Temozolomide Resistance Mechanisms via Genome-Wide CRISPR Libraries. Cells 2020, 9, 2573.

- Rocha, C.R.R.; Kajitani, G.S.; Quinet, A.; Fortunato, R.; Menck, C.F.M. NRF2 and glutathione are key resistance mediators to temozolomide in glioma and melanoma cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 48081–48092.

- Cao, J.Y.; Poddar, A.; Magtanong, L.; Lumb, J.H.; Mileur, T.R.; Reid, M.A.; Dovey, C.M.; Wang, J.; Locasale, J.W.; Stone, E.; et al. A Genome-wide Haploid Genetic Screen Identifies Regulators of Glutathione Abundance and Ferroptosis Sensitivity. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 1544–1556.e8.

- Hassannia, B.; Wiernicki, B.; Ingold, I.; Qu, F.; Van Herck, S.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Bayır, H.; Abhari, B.A.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Choi, S.M.; et al. Nano-targeted induction of dual ferroptotic mechanisms eradicates high-risk neuroblastoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3341–3355.

- Li, S.; He, Y.; Chen, K.; Sun, J.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, Q. RSL3 Drives Ferroptosis through NF-κB Pathway Activation and GPX4 Depletion in Glioblastoma. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1–10.

- He, Y.; Ye, Y.; Tian, W.; Qiu, H. A Novel lncRNA Panel Related to Ferroptosis, Tumor Progression, and Microenvironment is a Robust Prognostic Indicator for Glioma Patients. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 788451.

- Zheng, J.; Zhou, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, X. A Prognostic Ferroptosis-Related lncRNAs Signature Associated With Immune Landscape and Radiotherapy Response in Glioma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 675555.

- Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zhuang, S.; Song, G.; Lv, Y.; Lin, Y. Over-expression of lncRNA TMEM161B-AS1 promotes the malignant biological behavior of glioma cells and the resistance to temozolomide via up-regulating the expression of multiple ferroptosis-related genes by sponging hsa-miR-27a-3p. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 1–12.

- Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, B.W.; Zhang, Z.B.; Deng, Q.J. Circular RNA TTBK2 regulates cell proliferation, invasion and ferroptosis via miR-761/ITGB8 axis in glioma. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 2585–2600.

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Long, X.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z. CircCDK14 Promotes Tumor Progression and Resists Ferroptosis in Glioma by Regulating PDGFRA. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 841–857.

- Latunde-Dada, G.O. Ferroptosis: Role of lipid peroxidation, iron and ferritinophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1893–1900.

- Gao, M.; Monian, P.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, J.; Jiang, X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 1021–1032.

- Liu, H.-J.; Hu, H.-M.; Li, G.-Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.-Y.; Zhang, C.-B.; Jiang, T. Ferroptosis-Related Gene Signature Predicts Glioma Cell Death and Glioma Patient Progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 538.

- Chen, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, H.; Wang, N.; Peng, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Amentoflavone suppresses cell proliferation and induces cell death through triggering autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in human glioma. Life Sci. 2020, 247, 117425.

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, W.; Lu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lu, H.; Tan, G.; Wang, Z. New Autophagy-Ferroptosis Gene Signature Predicts Survival in Glioma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 739097.

- Sun, W.; Yan, J.; Ma, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y. Autophagy-Dependent Ferroptosis-Related Signature is Closely Associated with the Prognosis and Tumor Immune Escape of Patients with Glioma. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 253–270.

- Lee, S.Y. Temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma multiforme. Genes Dis. 2016, 3, 198–210.

- Hu, Z.; Mi, Y.; Qian, H.; Guo, N.; Yan, A.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X. A Potential Mechanism of Temozolomide Resistance in Glioma–Ferroptosis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 897.

- Mitre, A.-O.; Florian, A.I.; Buruiana, A.; Boer, A.; Moldovan, I.; Soritau, O.; Florian, S.I.; Susman, S. Ferroptosis Involvement in Glioblastoma Treatment. Medicina 2022, 58, 319.

- Zhuo, S.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, K. Clinical and Biological Significances of a Ferroptosis-Related Gene Signature in Glioma. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 590861.

- Chen, T.-C.; Chuang, J.-Y.; Ko, C.-Y.; Kao, T.-J.; Yang, P.-Y.; Yu, C.-H.; Liu, M.-S.; Hu, S.-L.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Chan, H.; et al. AR ubiquitination induced by the curcumin analog suppresses growth of temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma through disrupting GPX4-Mediated redox homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2020, 30, 101413.

- Yi, R.; Wang, H.; Deng, C.; Wang, X.; Yao, L.; Niu, W.; Fei, M.; Zhaba, W. Dihydroartemisinin initiates ferroptosis in glioblastoma through GPX4 inhibition. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20193314.

- Chen, Y.; Mi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Q.; Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Xing, J.; Hou, B.; Li, H.; et al. Dihydroartemisinin-induced unfolded protein response feedback attenuates ferroptosis via PERK/ATF4/HSPA5 pathway in glioma cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 402.

- Gao, X.; Guo, N.; Xu, H.; Pan, T.; Lei, H.; Yan, A.; Mi, Y.; Xu, L. Ibuprofen induces ferroptosis of glioblastoma cells via downregulation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 signaling pathway. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2020, 31, 34.

- Wang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, S.; Wang, C.; He, C.; Wang, L.; Piao, M.; Chi, G.; Luo, Y.; et al. Pseudolaric acid B triggers ferroptosis in glioma cells via activation of Nox4 and inhibition of xCT. Cancer Lett. 2018, 428, 33.

- Koike, N.; Kota, R.; Naito, Y.; Hayakawa, N.; Matsuura, T.; Hishiki, T.; Onishi, N.; Fukada, J.; Suematsu, M.; Shigematsu, N.; et al. 2-Nitroimidazoles induce mitochondrial stress and ferroptosis in glioma stem cells residing in a hypoxic niche. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 1–13.

- Abdalkader, M.; Lampinen, R.; Kanninen, K.M.; Malm, T.M.; Liddell, J.R. Targeting Nrf2 to Suppress Ferroptosis and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 466.

- Masaldan, S.; Bush, A.I.; Devos, D.; Rolland, A.S.; Moreau, C. Striking while the iron is hot: Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in neurodegeneration. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 221–233.

- Zhao, J.; Xu, B.; Xiong, Q.; Feng, Y.; Du, H. Erastin-induced ferroptosis causes physiological and pathological changes in healthy tissues of mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 1–8.

- Hambright, W.S.; Fonseca, R.S.; Chen, L.; Na, R.; Ran, Q. Ablation of ferroptosis regulator glutathione peroxidase 4 in forebrain neurons promotes cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 8–17.

- Xiong, Q.; Li, X.; Xia, L.; Yao, Z.; Shi, X.; Dong, Z. Dihydroartemisinin attenuates hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in neonatal rats by inhibiting oxidative stress. Mol. Brain 2022, 15, 1–10.

- Zhao, Y.; Long, Z.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, T.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, X.; Wang, K.; Feng, M.; et al. Dihydroartemisinin Ameliorates Learning and Memory in Alzheimer’s Disease Through Promoting Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion and Autolysosomal Degradation for Aβ Clearance. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 47.

- Shin, D.H.; Bae, Y.C.; Kim-Han, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, I.Y.; Son, K.H.; Kang, S.S.; Kim, W.-K.; Han, B.H. Polyphenol amentoflavone affords neuroprotection against neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage via multiple mechanisms. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 561–572.

- Le, T.T.; Kuplicki, R.; Yeh, H.-W.; Aupperle, R.L.; Khalsa, S.S.; Simmons, W.K.; Paulus, M.P. Effect of Ibuprofen on BrainAGE: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Response Exploratory Study. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 836–843.

- Hu, Y.; Tu, Z.; Lei, K.; Huang, K.; Zhu, X. Ferroptosis-related gene signature correlates with the tumor immune features and predicts the prognosis of glioma patients. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20211640.

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Gao, H.; Li, L. Prognostic Model and Nomogram Construction Based on a Novel Ferroptosis-Related Gene Signature in Lower-Grade Glioma. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 753680.

- Elgendy, S.M.; Alyammahi, S.K.; Alhamad, D.W.; Abdin, S.M.; Omar, H.A. Ferroptosis: An emerging approach for targeting cancer stem cells and drug resistance. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 155, 103095.

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jin, T.; Xu, K.; Liu, M.; Xu, H. Ferroptosis in Low-Grade Glioma: A New Marker for Diagnosis and Prognosis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e921947.

- Mooney, K.L.; Choy, W.; Sidhu, S.; Pelargos, P.; Bui, T.T.; Voth, B.; Barnette, N.; Yang, I. The role of CD44 in glioblastoma multiforme. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 34, 1–5.

- Affronti, H.C.; Wellen, K.E. Epigenetic Control of Fatty-Acid Metabolism Sustains Glioma Stem Cells. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1161–1163.

- Yamane, D.; Hayashi, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Imagawa, H.; Kohara, M.; Lemon, S.M.; Ichi, I. FADS2-dependent fatty acid desaturation dictates cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis and permissiveness for hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021, 29, 799–810.e4.

- Ye, H.; Huang, H.; Cao, F.; Chen, M.; Zheng, X.; Zhan, R. HSPB1 Enhances SIRT2-Mediated G6PD Activation and Promotes Glioma Cell. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164285.