Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Patricia Dias Fernandes | -- | 2459 | 2022-07-05 20:03:37 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 2459 | 2022-07-06 02:52:57 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | -7 word(s) | 2452 | 2022-07-12 11:10:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

França, P.R.D.C.; Lontra, A.C.P.; Fernandes, P.D. Treatment of Endometriosis. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24845 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

França PRDC, Lontra ACP, Fernandes PD. Treatment of Endometriosis. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24845. Accessed February 07, 2026.

França, Patricia Ribeiro De Carvalho, Anna Carolina Pereira Lontra, Patricia Dias Fernandes. "Treatment of Endometriosis" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24845 (accessed February 07, 2026).

França, P.R.D.C., Lontra, A.C.P., & Fernandes, P.D. (2022, July 05). Treatment of Endometriosis. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24845

França, Patricia Ribeiro De Carvalho, et al. "Treatment of Endometriosis." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

Endometriosis is a gynecological condition characterized by the growth of endometrium-like tissues inside and outside the pelvic cavity. The evolution of the disease can lead to infertility in addition to high treatment costs. The available medications are only effective in treating endometriosis-related pain.

endometriosis

gynecological disease

inflammation

drug therapy

1. Introduction

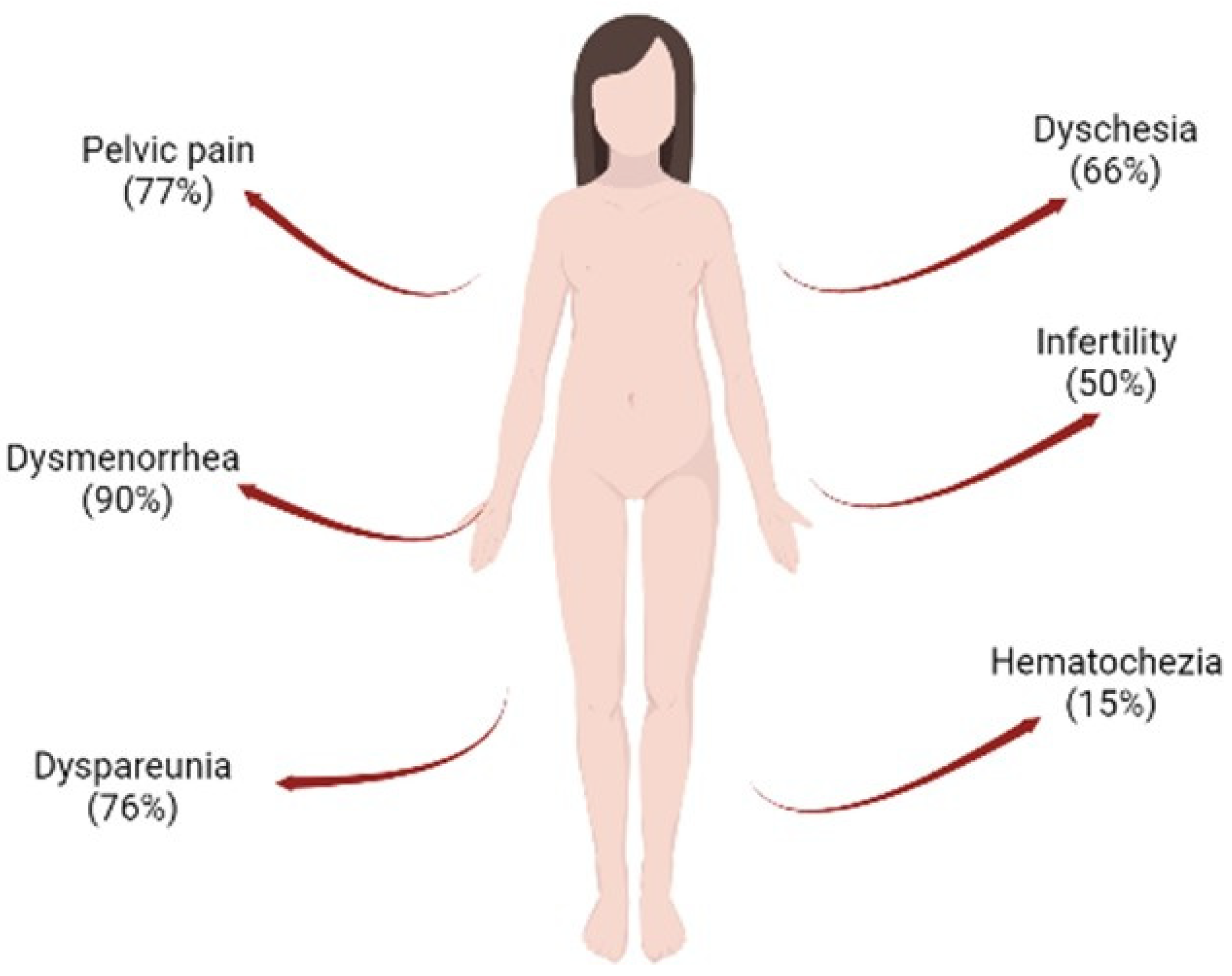

Currently, 190 million women worldwide present with endometriosis [1]. Endometriosis is a chronic, hormone-dependent inflammatory disease defined by the presence of foci of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity, which can be found mostly in the pelvic cavity, but can also be found in the ovaries, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, appendix, upper abdomen, among others [2]. In the general population, rates of the disease are difficult to quantify due to difficulties in a definitive diagnosis and asymptomatic cases, thus aggravating the condition of endometriosis. Therefore, estimates vary widely between different population samples and modes of diagnosis, all influenced by the presentation of symptoms and access to care [3]. Despite this limitation, the prevalence of endometriosis is greater than 10% in women in the reproductive period [4]. It is observed that 90% suffer from dysmenorrhea, 76% from dyspareunia, 77% from chronic pelvic pain, 66% from dyschesia, and 15% from hematochezia [5]. One of the most common complications in endometriosis is infertility, a symptom that occurs in 50% of women diagnosed with the disease (Figure 1). These symptoms compromise women’s quality of life, especially in relation to noncompliance with activities of daily living, personal relationships, and low productivity at work [6]. In addition, many studies report the correlation between anxiety and depression with pain symptoms and loss of fertility, leading to a rate of almost 87% of women with endometriosis developing some type of psychiatric disorder [7].

Figure 1. Common associated problems observed in women with endometriosis. The following can be observed: hematochezia (15%), infertility (50%), dyschesia (66%), dyspareunia (76%), pelvic pain (77%), and dysmenorrhea (90%). Figure created in BioRender.com.

Endometriosis impacts different aspects of life, and one of them is the economic aspect. A large multicentre study carried out between Europe, UK, and the USA showed that the total cost per woman with endometriosis per year was approximately EUR 9579.00, with most of the costs (EUR 6298.00) caused by the absence or reduction of effectiveness at work resulting from the symptoms of the disease [8][9]. Medical care costs (EUR 3281.00) were mainly due to surgeries (29%), monitoring exams (19%), hospitalization (18%), and medical visits (16%) [10].

2. Treatment of Endometriosis

Currently, the most accurate diagnosis of endometriosis is laparoscopy, with inspection of the abdominal cavity and histological confirmation of suspicious lesions. This type of diagnosis is particularly useful for detecting, through biopsies, occult microscopic lesions in women with and without visible endometriosis. However, this method is expensive and invasive, offering risks to the patient related to the procedure, such as bleeding and infections. Thus, other methods may have advantages when compared to this one, such as imaging methods and biomarkers [11]. Imaging methods such as transvaginal ultrasound (TV-USG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are suitable for the diagnosis of two phenotypes of endometriosis. The deep infiltrative endometriosis, which can occur in the rectosigmoid, uterosacral, and rectovaginal septum ligaments, and endometriomas, a condition in which USG-TV is the method of first choice. In addition, sigmoid, ileocecal, and urological lesions can be detected with complementary radiological techniques, such as transrectal ultrasound, multidetector computed tomography, or MRI. Scintigraphy can also be used to explore renal function in cases of suspected ureteral endometriosis. Ultrasonography and MRI have high sensitivity (91%) and specificity (98%) to detect and rule out endometriotic lesions, especially deep lesions. However, they are not advisable for the identification of peritoneal lesions, mainly due to the size of the lesions, which is below the detection limit of the devices [12].

Blood, endometrial tissue, and urine biomarkers can be used as markers for the diagnosis of endometriosis. However, such biomarkers are not able to reveal the location of endometriotic lesions. A widely used biomarker is CA-125; despite being found at high levels in endometriosis, CA-125 can be elevated in several diseases. Thus, it has no value as a single test in the diagnosis of the disease [11]. Another option could be the use of questionnaires with internally and externally validated scores of clinical values that could indicate those patients at high-risk of endometriosis [13].

The choice of treatment will depend on the severity of symptoms, the extent and location of the disease, the desire to become pregnant, and the patient’s age. It can be through medication, surgery, or even a combination of both. Pharmacological therapy for endometriosis aims to improve symptoms or prevent recurrence of postsurgical disease [14]. Hormonal treatments act by suppressing fluctuations in gonadotropic and ovarian hormones, resulting in the inhibition of ovulation, menstruation, and a reduction in the inflammatory process [6].

Given this, some drugs create environments such as hyperprogestogenic therapy (combined oral contraceptives and progestins). These drugs are the first choice; they act by inhibiting ovulation, decidualization, and result in a decrease in the size of the lesions. In addition, they are available in a variety of dosage forms, improve pain symptoms in most patients, are well tolerated, and are inexpensive. However, 25% of the patients do not respond to treatment, in addition to having adverse effects such as: sudden bleeding, breast tenderness, nausea, headaches, mood swings, among others [15][16]. Hypoestrogenic therapy (Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone—GnRH agonists) represents the second line of treatment for this disease. It is an effective drug in the treatment of women who do not respond to combined oral contraceptives or progestins. GnRH agonists provide negative feedback mechanisms in the pituitary, inhibition of gonadotropin secretion, and subsequent downregulation of ovarian steroidogenesis. One of the main disadvantages of these drugs is that they are not administered orally, as they are destroyed in the digestive process, so their use is indicated parenterally, subcutaneously, intramuscularly, via nasal spray, or intravaginally. The use of these drugs is associated with poorly tolerated adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms, genital hypotrophy, and mood instability. In addition, GnRH agonists cause a negative calcium balance with an increased risk of osteopenia, although bone loss seems to be reversible if the treatment is limited to a few months [15]. Hyperandrogenic therapy (danazol or gestrinone) produces a pseudomenopause by inhibiting the release of GnRH and the peak of luteinizing hormone (LH) increases the levels of androgen hormones (free testosterone) and decreases estrogen levels (inhibits ovarian production), which causes atrophy of endometriotic implants. However, this class of drugs is not suitable for prolonged treatments, mainly due to androgenic effects, i.e., seborrhea, hypertrichosis, weight gain, unfavorable effects on the distribution of serum lipoprotein cholesterol, a decrease in HDL levels and an increase in LDL levels [17].

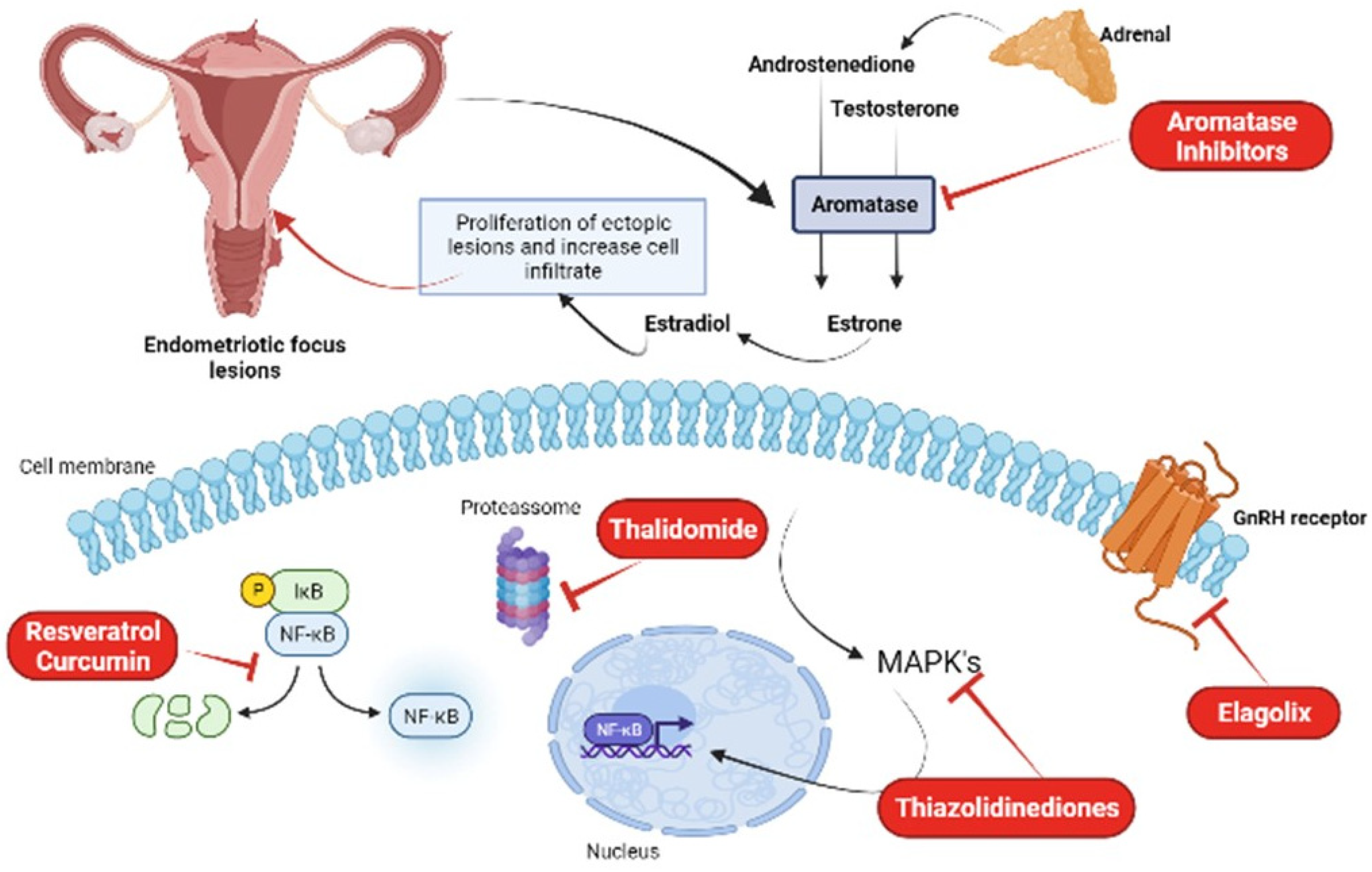

Most hormonal treatments for endometriosis focus on inhibiting ovarian estrogen production, rather than blocking estrogen produced locally in endometriotic lesions. Aromatase inhibitors (AI) are a new class of drugs on the market, which are highly specific and act by inhibiting the P450 aromatase enzyme, the final enzyme in the estrogen biosynthesis pathway, in order to stop the local production of this hormone. The use of these drugs significantly reduces the size of lesions, as well as pelvic pain. However, in premenopausal women, AIs need to be combined with other classes of drugs, such as progestin, combined oral contraceptives, or a GnRH agonist. It was observed that the best combination, with minimal adverse effects, was with oral contraceptives or progestin [18]. Its adverse symptoms are loss of calcium in the bones, causing an increased risk of osteoporosis, vaginal dryness, insomnia, vasomotor symptoms, nausea, and headaches. The most potent AIs are those from the 3rd generation, anastrozole and letrozole; they are administered orally and are able to reduce serum levels of 17β-estradiol by 97–99% after one day of use [19]. A randomized controlled clinical study performed by Zhao et al. [20] using a total of 820 patients and aiming to analyze the efficacy and tolerability of letrozole combined with combined oral contraceptives, showed that this combination reduced the intensity of pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dysmenorrhea throughout treatment, avoiding more severe adverse effects such as bone loss [20].

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used in association with all the other classes mentioned above. They are widely used in the treatment of chronic inflammatory conditions and are effective in relieving primary dysmenorrhea. However, they only act to minimize symptoms and do not block ovulation. Patients who use these drugs should consider the adverse effects gastric ulcers, cardiovascular events, and acute renal failure [11].

Blocking the specific NFkB DNA-binding sites at promoter regions is another possible strategy [21] that has been used successfully with endometriotic stromal cells in vitro. This inhibition reduces RANTES production and MCP-1 activity induced by IL-1β [22].

Pharmaceuticals with off-target effects on NFkB have also been considered for endometriosis treatment. Thalidomide inhibits NFkB through the suppression of IkB degradation [23]. Treatment of endometriotic stromal cells with thalidomide inhibited TNFa-stimulated IL-8 production and secretion [24]. Thiazolidinediones, a group of drug ligands for PPARg developed for diabetes treatment, was also used as an inhibitor of this pathway and for the reduction of endometriotic stromal cells [25]. A study by McKinnon et al. (2012a) found that the use of these drugs reduced the size of endometriotic lesions in both rats and primates [26]. These drugs, however, also produce adverse effects on skeletal health [26].

Given the upstream convergence of the three MAPK pathways (ERK1/2, p38, and JNK), attempts have been made to target shared upstream mediators. Specific inhibitors of B-raf, Vemurafenib and Dabrafenib, have been approved for use in melanoma; however, significant side effects exist [27]. Similar side effects have also been observed in the use of the MEK inhibitor, Trametinib [28]. Therefore, as long-term therapy is required to treat chronic inflammation, global inhibitors of JNK1 and p38a by orally applied kinase inhibitors at this stage appear unlikely candidates [25].

When symptoms persist or adverse effects outweigh the beneficial effects of drugs, surgical treatment is indicated. Patients who present with anatomical distortion of pelvic structures, adhesions, intestinal or urinary tract obstruction are also eligible to undergo surgery. Conservative surgery consists of cauterization of endometriotic foci and restoration of pelvic anatomy. With the excision of ectopic foci, a significant improvement in pelvic pain and fertility rate are observed, although recurrence of disease symptoms may reappear after surgery. Definitive surgery involves hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy (depending on the age of the patient). This in turn is indicated when there is severity of the disease including persistence of disabling symptoms after conservative drug or surgical therapy. Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with excision of all foci of endometriosis showed cure rates of 90% [12].

New Treatment Options

Elagolix

Elagolix is an orally administered GnRH antagonist capable of partially suppressing estradiol, unlike GnRH agonists, thus preventing the creation of a hypoestrogenic state in patients and reducing adverse effects. This drug proved to be effective in reducing symptoms such as dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain, increasing patients’ productivity at work, and improving their quality of life. Treatment with Elagolix, however, is not recommended for patients who have not responded to treatment with GnRH agonists and antagonists, as well as pregnant women, and patients with osteoporosis and severe liver failure. A randomized double-blind phase three study by Taylor et al. [29] involving 872 women treated with doses of 150 mg and 200 mg of Elagolix for six months showed that almost 70% of these patients reported at least one adverse effect during treatment. Despite this, Elagolix, which has antiproliferative effects, was effective in reducing dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain associated with endometriosis [30].

Resveratrol

It is known that one of the characteristics of endometriosis is exacerbated oxidative stress, which in addition to damaging cells, also influences the expression of NF-кB, associated with the production of cytokines, angiogenic factors, iNOS and COX. Resveratrol, which is a polyphenol, is a new drug that is undergoing clinical trials and can induce the production of antioxidant enzymes, increasing the antioxidant capacity of tissues by 50%, in addition to inhibiting the expression of IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and COX-2, presenting an anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic effect by inhibiting VEGF expression. In addition, this drug also inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species by monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes and negatively affects the process of cell proliferation promoted by NF-кB and, by inhibiting it, also reduces the epithelium–mesenchymal transition, essential for the establishment of endometriotic lesions, through the PI3K/AKT/NF-ΚB pathway and the regulation of genes related to this transition [31][32][33].

Curcumin

Some bioactive components found in plants have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that are effective in the treatment of endometriosis, such as curcumin, for example, a natural product extracted from Curcuma longa L., traditionally used in some Asian countries to treat diseases. Curcumin can significantly reduce the expression of COX-2, the production of TNF-α and IL-6, and decrease the epithelium–mesenchymal transition, essential for the development of endometriosis [11][34]. In addition, it can also reduce cell proliferation, decrease the size of endometriotic lesions, generate a reduction in matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity, and reduce VEGF expression, thus having an antiangiogenic character [35]. Chowdhury and collaborators demonstrated in their study that the effects of curcumin treatment on eutopic endometrial cells from endometriosis patients significantly reduce the secretion of inflammatory cytokines in these cells, also decreasing the phosphorylation of IKKα/β, NF-κB, STAT3, and JNK signaling pathways [36].

Puerarin

Puerarin is an isoflavonoid found in Pueraria lobata, used in the treatment of cardiovascular and neurological diseases. Due to its ability to inhibit aromatase enzyme activity in endometrial cells and suppress cell adhesion and proliferation, it constitutes a possible new treatment against endometriosis [35][37]. A study by Yu et al. [38] showed that treatment with puerarin reduced the levels of estradiol and PGE2 in endometriotic rats, by inhibiting the aromatase enzyme P450 and COX-2, in addition to increasing the expression of 17β-HSD2, thus preventing the growth of endometrial tissue. Kim et al. [39][40][41][42] showed that treatment with an extract obtained from flowers of P. lobata reduced the adhesion and migration of these cells, also reducing the formation of endometriotic lesions in mice. Figure 2 summarizes the main treatment options for endometriosis.

Figure 2. New treatment options for the treatment of endometriosis: aromatase inhibitors, thalidomide, thiazolidinediones, elagolix, resveratrol, and curcumin. Figure created in Biorender.com.

Many gynecological societies have published different guidelines in order to help in the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. However, the variety of the available treatments and the complexity of this illness leads to significant discrepancies between recommendations. Six national guidelines (the College National des Gynecologues et Obstetriciens Francais, the National German Guideline, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and the National Institute for Health and Care) and two internationals (the World Endometriosis Society and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology) are widely used around the globe to identify the disease. All the above-mentioned guidelines agree that the combined oral contraceptive pill, progestogens, are therapies recommended for endometriosis-associated pain. Concerning infertility, there is no clear consensus about surgical treatment. Discrepancies are also found in recommendation of the second- and third-line treatments [10].

References

- Rasheed, H.A.M.; Hamid, P. Inflammation to Infertility: Panoramic View on Endometriosis. Cureus 2020, 12, e11516.

- Macer, M.L.; Taylor, H.S. Endometriosis and Infertility: A Review of The Pathogenesis and Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Infertility. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 39, 535–549.

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256.

- Szukiewicz, D.; Stangret, A.; Ruiz-Ruiz, C.; Olivares, E.G.; Soriţău, O.; Suşman, S.; Szewczyk, G. Estrogen- And Progesterone (P4)-Mediated Epigenetic Modifications of Endometrial Stromal Cells (Enscs) And/Or Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (Mscs) In the Etiopathogenesis of Endometriosis. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021, 17, 1174–1193.

- Bem-Meir, L.C.; Soriano, D.; Zajicek, M.; Yulzari, V.; Bouaziz, J.; Beer-Gabel, M.; Eisenberg, V.H. The Association Between Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Transvaginal Ultrasound Findings in Women Referred for Endometriosis Evaluation: A Prospective Pilot Study. Ultraschall Med. 2020, 1300–1887.

- Chapron, C.; Marcellin, L.; Borghese, B.; Santulli, P. Rethinking Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Management of Endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 666–682.

- Farshi, N.; Hasanpour, S.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Esmaeilpour, K. Effect of Self-Care Counselling on Depression and Anxiety in Women With Endometriosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 391.

- Pokrzywinski, R.M.; Soliman, A.M.; Chen, J.; Snabes, M.C.; Coyne, K.S.; Surrey, E.S.; Taylor, H.S. Achieving Clinically Meaningful Response in Endometriosis Pain Symptoms Is Associated with Improvements in Health-Related Quality of Life and Work Productivity: Analysis Of 2 Phase Iii Clinical Trials. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, e1–e592.

- Soliman, A.M.; Rahal, Y.; Robert, C.; Defoy, I.; Nisbet, P.; Leyland, N.; Singh, S. Impact of Endometriosis on Fatigue and Productivity Impairment in A Cross-Sectional Survey of Canadian Women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2021, 43, 10–18.

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; Brodszky, V.; Canis, M.; Colombo, G.L.; Deleire, T.; et al. The Burden of Endometriosis: Costs and Quality of Life of Women with Endometriosis and Treated in Referral Centres. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1292–1299.

- Da Broi, M.G.D.; Ferriani, R.A.; Navarro, P.A. Ethiopathogenic Mechanisms of Endometriosis—Related Infertility. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2019, 23, 273–280.

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Koga, K.; Missmer, S.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Viganò, P. Endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 1–25.

- Chapron, C.; Lafay-Pillet, M.C.; Santulli, P.; Bourdon, M.; Maignien, C.; Gaudet-Chardonnet, A.; Maitrot-Mantelet, L.; Borghese, B.; Marcellin, L. A new validated screening method for endometriosis diagnosis based on patient questionnaires. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101263.

- Prins, J.R.; Gomes-Lopez, N.; Robertsona, S.A. Interleukin-6 In Pregnancy and Gestational Disorders. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2012, 95, 1–14.

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275.

- Ferrero, S.; Barra, F.; Maggiore, U.L.R. Current and Emerging Therapeutics for The Management of Endometriosis. Drugs 2018, 78, 995–1012.

- Kiesel, L.; Sourouni, M. Diagnosis of Endometriosis in the 21st Century. Climacteric 2019, 22, 296–302.

- Bulun, S.E.; Yilmar, B.D.; Sison, C.; Miyazaki, K.; Bernardi, L.; Liu, S.; Kohlmeier, A.; Yin, P.; Milad, M.; Wei, J. Endometriosis. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1048–1079.

- Falcone, T.; Flyckt, R. Clinical Management of Endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 557–571.

- Johnson, N.P.; Hummelshoj, L.E. Consensus on Current Management of Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1552–1568.

- Khaled, A.R.; Butfiloski, E.J.; Sobel, E.S.; Schiffenbauer, J. Use of phosphorothioate-modified oligodeoxynucleotides to inhibit NF-kappaB expression and lymphocyte function. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1998, 86, 170–179.

- Xiu-li, W.; Su-ping, H.; Hui-hua, D.; Zhi-xue, Y.; Shi-long, F.; Pin-hong, L. NF-kappaB decoy oligonucleotides suppress RANTES expression and monocyte chemotactic activity via NF-kappaB inactivation in stromal cells of ectopic endometrium. J. Clin. Immunol. 2009, 29, 387–395.

- Majumdar, S.; Lamothe, B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Thalidomide suppresses NF-kappa B activation induced by TNF and H2O2, but not that activated by ceramide, lipopolysaccharides, or phorbol ester. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 2644–2651.

- Yagyu, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Matsuzaki, H.; Wakahara, K.; Kondo, T.; Kurita, N.; Sekino, H.; Inagaki, K.; Suzuki, M.; Kanayama, N.; et al. Thalidomide inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced interleukin-8 expression in endometriotic stromal cells, possibly through suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 3017–3021.

- McKinnon, B.; Bersinger, N.A.; Mueller, M.D. Peroxisome proliferating activating receptor gamma-independent attenuation of interleukin 6 and interleukin 8 secretion from primary endometrial stromal cells by thiazolidinediones. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97, 657–664.

- Lebovic, D.I.; Mwenda, J.M.; Chai, D.C.; Mueller, M.D.; Santi, A.; Fisseha, S.; D’Hooghe, T. PPAR-gamma receptor ligand induces regression of endometrial explants in baboons: A prospective, randomized, placebo- and drug-controlled study. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 88, 1108–1119.

- Su, F.; Viros, A.; Milagre, C.; Trunzer, K.; Bollag, G.; Spleiss, O.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Kong, X.; Koya, R.C.; Flaherty, K.T.; et al. RAS mutations in cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 207–215.

- Menzies, F.M.; Fleming, A.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 345–357.

- Harada, T.; Taniguchi, F.; Onishi, K.; Kurozawa, Y.; Hayashi, K. Group JECsS obstetrical complications in women with endometriosis: A cohort study in Japan. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168476.

- Słopień, R.; Męczekalski, B. Aromatase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Endometriosis. Prz. Menopauzalny 2016, 15, 43–47.

- Zhao, Y.; Luan, X.; Wang, Y. Letrozole Combined with Oral Contraceptives versus Oral Contraceptives Alone in the Treatment of Endometriosis-Related Pain Symptoms: A Pilot Study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 51–55.

- Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.C.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.S.; Kotarski, J.; Archer, D.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Surrey, E.; Johnson, N.P.; Watts, N.B.; et al. Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 28–40.

- Harlev, A.; Gupta, S.; Agarwal, A. Targeting Oxidative Stress to Treat Endometriosis. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2015, 19, 1447–1464.

- Miller, J.E.; Ahn, S.H.; Marks, R.M.; Monsanto, S.P.; Fazleabas, A.T.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. Il-17a Modulates Peritoneal Macrophage Recruitment and M2 Polarization in Endometriosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 108.

- Nagayasu, M.; Imanaka, S.; Kimura, M.; Maruyama, S.; Kobayashi, H. Nonhormonal Treatment for Endometriosis Focusing on Redox Imbalance. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2021, 86, 1–12.

- Loh, C.-Y.; Chai, J.Y.; Tang, T.F.; Wong, W.F.; Sethi, G.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Chong, P.P.; Looi, C.Y. The E-Cadherin and N-Cadherin Switch in Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: Signaling, Therapeutic Implications, and Challenges. Cells 2019, 8, 1118.

- Meresman, G.F.; Götte, M.; Laschke, M.W. Plants as Source of New Therapies for Endometriosis: A Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Hum. Reprod. Update 2021, 27, 367–392.

- Chowdhury, I.; Banerjee, S.; Driss, A.; Xu, W.; Mehrabi, S.; Nezhat, C.; Sidell, N.; Taylor, R.N.; Thompson, W.E. Curcumin Attenuates Proangiogenic and Proinflammatory Factors in Human Eutopic Endometrial Stromal Cells through the NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 6298–6312.

- Cai, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, S.-J.; Jiang, S.-W. Phytoestrogens for the Management of Endometriosis: Findings and Issues. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 569.

- Yu, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhai, D.; Shen, W.; Bai, L.; Liu, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, J.; Yu, C. The Effects and Possible Mechanisms of Puerarin to Treat Endometriosis Model Rats. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 269138.

- Kim, J.-H.; Woo, J.-H.; Kim, H.M.; Oh, M.S.; Jang, D.S.; Choi, J.-H. Anti-Endometriotic Effects of Pueraria Flower Extract in Human Endometriotic Cells and Mice. Nutrients 2017, 9, 212.

- Kalaitzopoulos, D.R.; Samartzis, N.; Kolovos, G.N.; Mareti2, E.; Samartzis, E.P.; Eberhard, M.; Dinas, K.; Daniilidis, A. Treatment of endometriosis: A review with comparison of 8 guidelines. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 397.

More

Information

Subjects:

Pharmacology & Pharmacy

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

12 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No