| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nada Akaree | -- | 4714 | 2022-07-05 14:06:29 | | | |

| 2 | Nada Akaree | Meta information modification | 4714 | 2022-07-05 14:12:28 | | | | |

| 3 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 4714 | 2022-07-06 08:28:32 | | |

Video Upload Options

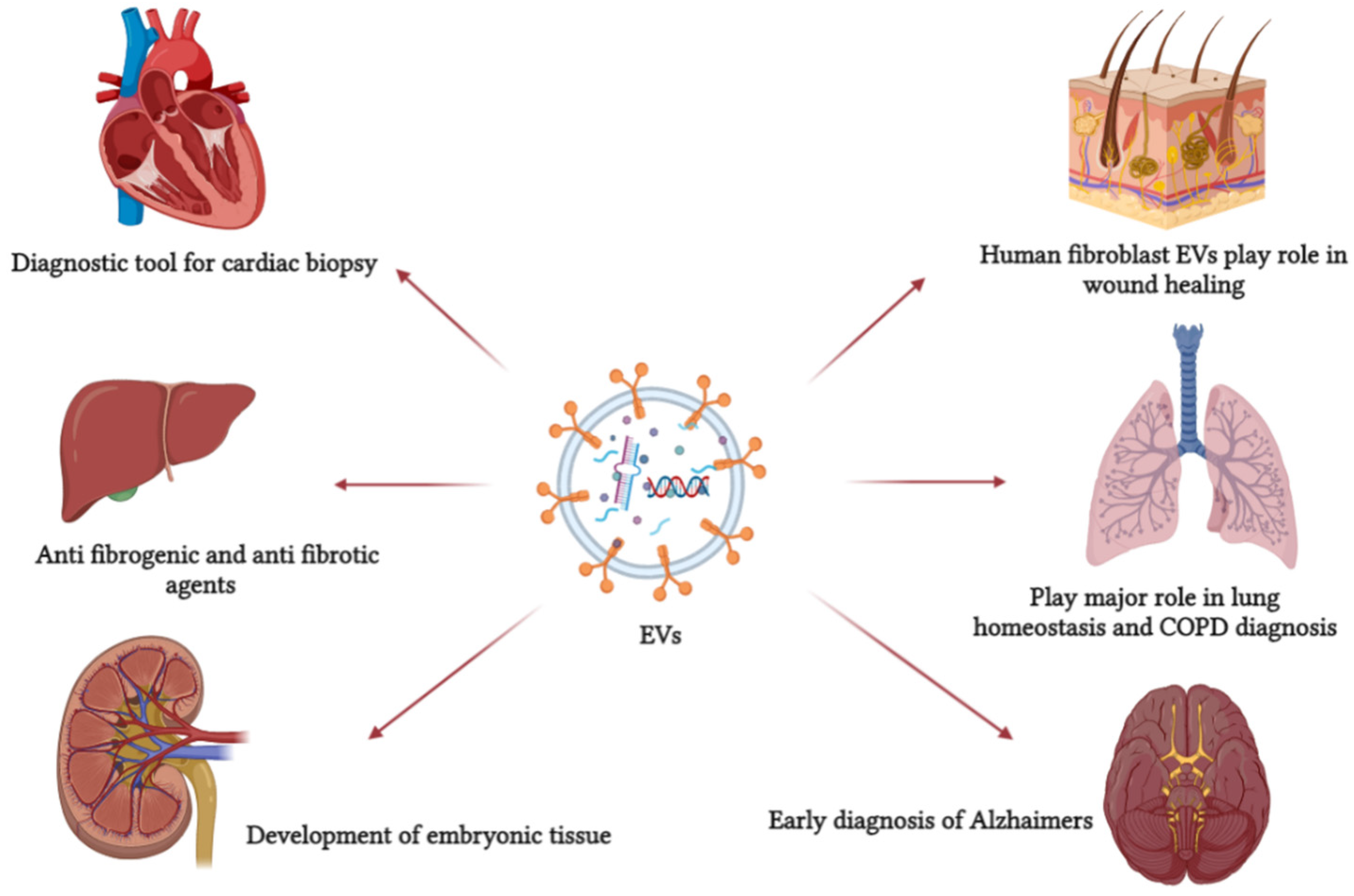

Extracellular vesicles (Evs) can be found in all biological fluids, making them the perfect non-invasive diagnostic tool, as their cargo causes functional changes in the cells upon receiving, unlike synthetic drug carriers. EVs last longer in circulation and instigate minor immune responses, making them the perfect drug carrier.

1. Introduction

2. Classification and Biogenesis of EVs

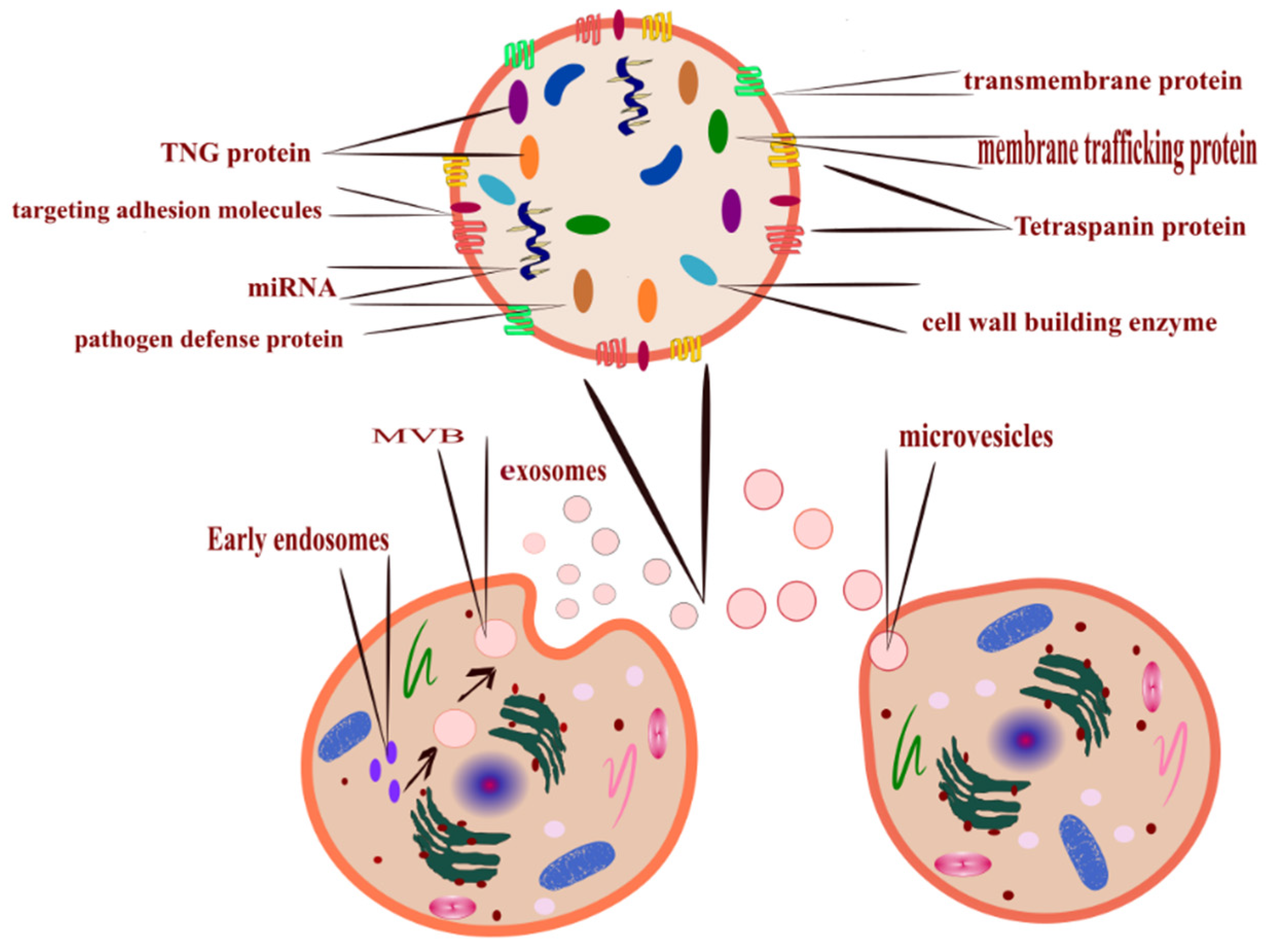

- Outward budding of the plasma membrane (shedding microvesicles, MVs) happens when the plasma membrane is reacting to external incitements such as inflammatory cytokines that provoke a response from the cell [17], leading to activation of the plasma membrane that will eventually release sacs 100–1000 nm in diameter that are released into the external surroundings including microparticles and microvesicles [18].

- Inward budding of the endosomal membrane (early endosomes) results in the formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs); these small size particles range in diameter 30–200 nm [18] and 30–150 nm [19]. The releasing mechanism of these MVBs starts by forming a sac inside the cell containing vesicles derived from the mother cell; eventually, these sacs will emerge with the plasma membrane and be released into the extracellular space, becoming exosomes [20].

- Apoptosis-derived EVs (ApoBDs). In this case, the vesicles are large in diameter (800–5000 nm); the mechanism of release occurred during programmed cell death [21]; eventually, these vesicles will be released into the extracellular space and become another type of EV [22].

3. EV Cargo and Uptake

3.1. EV RNA

3.2. Protein

|

Common Markers Used for the Characterisation of EVs |

Reference |

|---|---|

|

Cytosolic ESCRT 1 |

[39] |

|

Rabs 2 |

|

|

HSPA5 3, cell growth proteins (GSN 4 and FSCN1 5) ATPase family 6 (ATP1A1, ATP1B1, and ATP2B1) signal protein (ROCK2 7, ANXA1 8, CORO1B 9, and ARF1 10)Cell communication proteins (ANXA6 11, LYN 12, OXTR 13, STX4 14, and GNB1 15) Cation transporters |

[14] |

|

Cytoskeletal proteins (ACTG1 16, DSTN 17, FLNA 18, COTL1 19, KRT1 20, KRT9, KRT10, MSN 21, PFN1 22, and WDR1 23) |

[26] |

|

TSG101 24 and LAMP1 25 |

[40] |

|

Lipid raft-associated protein (Flot1) 26 |

[27] |

|

Lipid raft cellular prion protein (PrP) 27 |

[2] |

|

Tetraspanin |

[41] |

|

ALIX 28 part of EVs release |

[42] |

|

VPS4B 29 and HSP70 30 |

[43] |

3.3. EV Uptake

4. Plant-Derived EVs

|

Plant Source |

Findings |

References |

|---|---|---|

|

Ginger and carrots |

The isolated EVs are similar in structure to mammal derived EVs and involved in cellular communication and plant defense response. |

[49] |

|

Leaves of Dendropanax morbifera |

Similar in size to mammal EVs. Reduces the synthesis of UV-induced melanin, therefore can be used as a natural ingredient in cosmetic products. |

[13] |

|

Arabidopsis |

The EVs are saturated with a protein involved in stress and immune response in infected plant. |

[54] |

|

Watermelon |

The isolated EVs are comparable to animal EVs, and the predicted function includes regulation of the development, ripening, and metabolism process of the fruit. |

[55] |

|

Curcumin |

Delivery agent for a cancer drug induces a low immune response and cross mammalian parries. |

[56] |

|

Cotton |

Anti-fungal activity. |

[57] |

|

Coconut, kiwi, and Hami melon |

Detection of over 400 miRNA and the isolated EVs control inflammatory expression and gene-related cancer. |

[58] |

5. EV Function

|

Mammal Source |

Findings |

References |

|---|---|---|

|

Brain cells EVs |

Play a physiological and pathological role in the CNS. |

[66] |

|

Human breast milk EVs |

Contribute to the maturation process of the newborn, intestinal development, and microbial programming of infant tissue. Modify infant immune system. Support the cellular function and growth of the infant. |

|

|

Bovine breast milk-derived EVs |

Transport RNA to the receptor cell. Immunoregulatory function. |

[71] |

|

Embryonic stem cells EVs |

Enhanced proliferation of human tissue. |

[72] |

|

Pancreatic EVs |

Stimulation of T and B cells. |

[73] |

|

Giant panda breast milk EVs |

Immune system development and transfer of the genetic materials to the newborn cubs. |

[74] |

|

Zebrafish osteoblasts derived EVs |

Involved in the maturation of osteoclasts. |

[75] |

|

Oviduct derived EVs |

Improve the quality and development of the embryo. |

[76] |

|

Transport neurohormones to the embryo, and regulate the reactive oxygen in vitro. |

[77] |

|

|

Plasma-derived EVs |

Healing of cardiac cells. |

[37] |

|

Astrocyte derived EVs |

Neurodegeneration function. |

|

|

Mesenchymal stromal cells derived EVs |

Therapeutic function. |

[78] |

|

Umbilical cord-derived EVs |

Immunomodulatory function. |

6. EVs as a Disease Biomarker and Diagnostic Tool

7. Application of EVs as a Therapeutic or Drug Delivery Agent

References

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Bergamini, G.; Rajendran, L. Cell-to-Cell Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Focus on Microglia. Neuroscience 2019, 405, 148–157.

- Brenna, S.; Altmeppen, H.C.; Mohammadi, B.; Rissiek, B.; Schlink, F.; Ludewig, P.; Krisp, C.; Schlüter, H.; Failla, A.V.; Schneider, C.; et al. Characterization of Brain-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Reveals Changes in Cellular Origin after Stroke and Enrichment of the Prion Protein with a Potential Role in Cellular Uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1809065.

- Díaz-Varela, M.; de Menezes-Neto, A.; Perez-Zsolt, D.; Gámez-Valero, A.; Seguí-Barber, J.; Izquierdo-Useros, N.; Martinez-Picado, J.; Fernández-Becerra, C.; del Portillo, H.A. Proteomics Study of Human Cord Blood Reticulocyte-Derived Exosomes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11.

- Witwer, K.W.; Buzás, E.I.; Bemis, L.T.; Bora, A.; Lötvall, J.; Hoen, E.N.N.-; Piper, M.G.; Skog, J.; Théry, C.; Wauben, M.H.; et al. Standardization of Sample Collection, Isolation and Analysis Methods in Extracellular Vesicle Research. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2013, 2, 20360.

- Shah, R.; Patel, T.; Freedman, J.E. Circulating Extracellular Vesicles in Human Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 958–966.

- Witwer, K.W.; Théry, C. Extracellular Vesicles or Exosomes? On Primacy, Precision, and Popularity Influencing a Choice of Nomenclature Influencing a Choice of Nomenclature. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1648167.

- Witwer, K.W.; Van Balkom, B.W.M.; Bruno, S.; Choo, A.; Dominici, M.; Gimona, M.; Hill, A.F.; De Kleijn, D.; Koh, M.; Lai, R.C.; et al. Defining Mesenchymal Stromal Cell (MSC)-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles for Therapeutic Applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1609206.

- Kalra, H.; Drummen, G.P.C.; Mathivanan, S. Focus on Extracellular Vesicles: Introducing the next Small Big Thing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 170.

- Grabowska, K.; Wąchalska, M.; Graul, M.; Rychłowski, M.; Bieńkowska-Szewczyk, K.; Lipińska, A.D. Alphaherpesvirus Gb Homologs Are Targeted to Extracellular Vesicles, but They Differentially Affect MHC Class II Molecules. Viruses 2020, 12, 429.

- Saenz-Pipaon, G.; San Martín, P.; Planell, N.; Maillo, A.; Ravassa, S.; Vilas-Zornoza, A.; Martinez-Aguilar, E.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Alameda, D.; Lara-Astiaso, D.; et al. Functional and Transcriptomic Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles Identifies Calprotectin as a New Prognostic Marker in Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD). J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1729646.

- Xiao, Y.; Driedonks, T.; Witwer, K.W.; Wang, Q.; Yin, H. How Does an RNA Selfie Work? EV-Associated RNA in Innate Immunity as Self or Danger. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1793515.

- Costa Verdera, H.; Gitz-Francois, J.J.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Vader, P. Cellular Uptake of Extracellular Vesicles Is Mediated by Clathrin-Independent Endocytosis and Macropinocytosis. J. Control. Release 2017, 266, 100–108.

- Lee, R.; Ko, H.J.; Kim, K.; Sohn, Y.; Min, S.Y.; Kim, J.A.; Na, D.; Yeon, J.H. Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Plant Leaves and Stems in Mouse Melanoma Cells and Human Healthy Skin. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1703480.

- Mariscal, J.; Vagner, T.; Kim, M.; Zhou, B.; Chin, A.; Zandian, M.; Freeman, M.R.; You, S.; Zijlstra, A.; Yang, W.; et al. Comprehensive Palmitoyl-Proteomic Analysis Identifies Distinct Protein Signatures for Large and Small Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1764192.

- Skotland, T.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Lipids in Exosomes: Current Knowledge and the Way Forward. Prog. Lipid Res. 2017, 66, 30–41.

- Desrochers, L.M.; Antonyak, M.A.; Cerione, R.A. Extracellular Vesicles: Satellites of Information Transfer in Cancer and Stem Cell Biology. Dev. Cell 2016, 37, 301–309.

- Yamamoto, S.; Azuma, E.; Muramatsu, M.; Hamashima, T.; Ishii, Y.; Sasahara, M. Significance of Extracellular Vesicles: Pathobiological Roles in Disease. Cell Struct. Funct. 2016, 41, 137–143.

- Crescitelli, R.; Lässer, C.; Jang, S.C.; Cvjetkovic, A.; Malmhäll, C.; Karimi, N.; Höög, J.L.; Johansson, I.; Fuchs, J.; Thorsell, A.; et al. Subpopulations of Extracellular Vesicles from Human Metastatic Melanoma Tissue Identified by Quantitative Proteomics after Optimized Isolation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1722433.

- He, J.; Ren, W.; Wang, W.; Han, W.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Guo, M. Exosomal Targeting and Its Potential Clinical Application. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 12, 18.

- Bebelman, M.P.; Smit, M.J.; Pegtel, D.M.; Baglio, S.R. Biogenesis and Function of Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 188, 1–11.

- Poon, I.K.H.; Parkes, M.A.F.; Jiang, L.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; Tixeira, R.; Gregory, C.D.; Ozkocak, D.C.; Rutter, S.F.; Caruso, S.; Santavanond, J.P.; et al. Moving beyond Size and Phosphatidylserine Exposure: Evidence for a Diversity of Apoptotic Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Vitro. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1608786.

- Caruso, S.; Poon, I.K.H. Apoptotic Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: More than Just Debris. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1486.

- Lázaro-Ibáñez, E.; Lässer, C.; Shelke, G.V.; Crescitelli, R.; Jang, S.C.; Cvjetkovic, A.; García-Rodríguez, A.; Lötvall, J. DNA Analysis of Low- and High-Density Fractions Defines Heterogeneous Subpopulations of Small Extracellular Vesicles Based on Their DNA Cargo and Topology. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1656993.

- Lässer, C.; Jang, S.C.; Lötvall, J. Subpopulations of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Therapeutic Potential. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 60, 1–14.

- Anand, S.; Samuel, M.; Kumar, S.; Mathivanan, S. Ticket to a Bubble Ride: Cargo Sorting into Exosomes and Extracellular Vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Proteins Proteom. 2019, 1867, 140203.

- Choi, D.; Go, G.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Di Vizio, D.; Gho, Y.S. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Trypsin-Treated Extracellular Vesicles to Identify the Real-Vesicular Proteins. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1757209.

- Flemming, J.P.; Hill, B.L.; Haque, M.W.; Raad, J.; Bonder, C.S.; Harshyne, L.A.; Rodeck, U.; Luginbuhl, A.; Wahl, J.K.; Tsai, K.Y.; et al. MiRNA- and Cytokine-Associated Extracellular Vesicles Mediate Squamous Cell Carcinomas. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1790159.

- Williams, C.; Royo, F.; Aizpurua-olaizola, O.; Pazos, R.; Reichardt, N.; Falcon-perez, J.M.; Williams, C.; Royo, F.; Aizpurua-olaizola, O.; Pazos, R. Glycosylation of Extracellular Vesicles: Current Knowledge, Tools and Clinical Perspectives. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1442985.

- Thippabhotla, S.; Zhong, C.; He, M. 3D Cell Culture Stimulates the Secretion of in Vivo like Extracellular Vesicles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13012.

- Bahr, M.M.; Amer, M.S.; Abo-el-sooud, K.; Ahmed, N.; El-tookhy, O.S. Preservation Techniques of Stem Cells Extracellular Vesicles: A Gate for Manufacturing of Clinical Grade Therapeutic Extracellular Vesicles and Long-Term Clinical Trials. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2020, 8, 1–8.

- Elsharkasy, O.M.; Nordin, J.Z.; Hagey, D.W.; de Jong, O.G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Andaloussi, S.E.; Vader, P. Extracellular Vesicles as Drug Delivery Systems: Why and How? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 159, 332–343.

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R.F. Routes and Mechanisms of Extracellular Vesicle Uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 24641.

- Baldrich, P.; Rutter, B.D.; Karimi, H.Z.; Podicheti, R.; Meyers, B.C.; Innes, R.W. Plant Extracellular Vesicles Contain Diverse Small RNA Species and Are Enriched in 10- to 17-Nucleotide “Tiny” RNAs . Plant Cell 2019, 31, 315–324.

- Patton, J.G.; Franklin, J.L.; Weaver, A.M.; Vickers, K.; Zhang, B.; Coffey, R.J.; Ansel, K.M.; Blelloch, R.; Goga, A.; Huang, B.; et al. Biogenesis, Delivery, and Function of Extracellular RNA. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27494.

- Jabalee, J.; Towle, R.; Garnis, C. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: Cargo, Function, and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2018, 7, 93.

- Morad, G.; Moses, M.A. Brainwashed by Extracellular Vesicles: The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Primary and Metastatic Brain Tumour Microenvironment. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1627164.

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA Delivery by Extracellular Vesicles in Mammalian Cells and Its Applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 585–606.

- Ke, W.; Afonin, K.A. Exosomes as Natural Delivery Carriers for Programmable Therapeutic Nucleic Acid Nanoparticles (NANPs). Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 176, 113835.

- Liao, Z.; Jaular, L.M.; Soueidi, E.; Jouve, M.; Muth, D.C.; Schøyen, T.H.; Seale, T.; Haughey, N.J.; Ostrowski, M.; Théry, C.; et al. Acetylcholinesterase Is Not a Generic Marker of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1628592.

- Burbidge, K.; Zwikelmaier, V.; Cook, B.; Long, M.M.; Lonigro, M.; Ispas, G.; Rademacher, D.J.; Edward, M.; Burbidge, K.; Zwikelmaier, V.; et al. Cargo and Cell-Specific Differences in Extracellular Vesicle Populations Identified by Multiplexed Immunofluorescent Analysis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1789326.

- Yang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Cho, E.; Kim, G.B.; Kim, I.S. Extracellular Vesicles as a Platform for Membrane-Associated Therapeutic Protein Delivery. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1440131.

- De Jong, O.G.; Murphy, D.E.; Mäger, I.; Willms, E.; Garcia-guerra, A.; Gitz-francois, J.J.; Lefferts, J.; Gupta, D.; Steenbeek, S.C.; Van Rheenen, J.; et al. Vesicle-Mediated Functional Transfer of RNA. Nat. Commun. 2020, 2020, 1–13.

- Jiang, W.; Ma, P.; Deng, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Hepatitis A Virus Structural Protein PX Interacts with ALIX and Promotes the Secretion of Virions and Foreign Proteins through Exosome-like Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1716513.

- Beer, K.B.; Wehman, A.M. Mechanisms and Functions of Extracellular Vesicle Release in Vivo—What We Can Learn from Flies and Worms. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2017, 11, 135–150.

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.-M.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological Properties of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Physiological Functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066.

- Russell, A.E.; Sneider, A.; Witwer, K.W.; Bergese, P.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Cocks, A.; Cocucci, E.; Erdbrügger, U.; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; Freeman, D.W.; et al. Biological Membranes in EV Biogenesis, Stability, Uptake, and Cargo Transfer: An ISEV Position Paper Arising from the ISEV Membranes and EVs Workshop. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1684862.

- Nogués, L.; Benito-Martin, A.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Peinado, H. The Influence of Tumour-Derived Extracellular Vesicles on Local and Distal Metastatic Dissemination. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 60, 15–26.

- Wolf, T.; Baier, S.R.; Zempleni, J. The Intestinal Transport of Bovine Milk Exosomes Is Mediated by Endocytosis in Human Colon Carcinoma Caco-2 Cells and Rat Small Intestinal IEC-6 Cells123. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2201–2206.

- Zhang, M.; Xiao, B.; Wang, H.; Han, M.K.; Zhang, Z.; Viennois, E.; Xu, C.; Merlin, D. Edible Ginger-Derived Nano-Lipids Loaded with Doxorubicin as a Novel Drug-Delivery Approach for Colon Cancer Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1783–1796.

- Buschmann, D.; Kirchner, B.; Hermann, S.; Märte, M.; Wurmser, C.; Brandes, F.; Kotschote, S.; Bonin, M.; Steinlein, O.K.; Pfaffl, M.W.; et al. Evaluation of Serum Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Methods for Profiling MiRNAs by Next-Generation Sequencing. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1481321.

- Welsh, J.A.; Pol, E.; Bettin, B.A.; Carter, D.R.F.; Hendrix, A.; Lenassi, M.; Langlois, M.; Llorente, A.; Nes, A.S.; Nieuwland, R.; et al. Towards Defining Reference Materials for Measuring Extracellular Vesicle Refractive Index, Epitope Abundance, Size and Concentration. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1816641.

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Koo, Y.; Yang, A.; Dai, Y.; Khant, H.; Osman, S.R.; Chowdhury, M.; Wei, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Characterization of and Isolation Methods for Plant Leaf Nanovesicles and Small Extracellular Vesicles. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2020, 29, 102271.

- Cao, X.-H.; Liang, M.-X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, K.; Tang, J.-H.; Zhang, W. Extracellular Vesicles as Drug Vectors for Precise Cancer Treatment. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1519–1537.

- Rutter, B.D.; Innes, R.W. Extracellular Vesicles Isolated from the Leaf Apoplast Carry Stress-Response Proteins. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 728–741.

- Timms, K.; Holder, B.; Day, A.; McLaughlin, J.; Westwood, M.; Forbes, K. Isolation and Characterisation of Watermelon (Citrullus Lanatus) Extracellular Vesicles and Their Cargo. bioRxiv 2020, 791111.

- Rome, S. Biological Properties of Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 529–538.

- Rutter, B.D.; Innes, R.W. ScienceDirect Extracellular Vesicles as Key Mediators of Plant—Microbe Interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 44, 16–22.

- Xiao, J.; Feng, S.; Wang, X.; Long, K.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Tang, Q.; Jin, L.; Li, X.; et al. Identification of Exosome-like Nanoparticle-Derived MicroRNAs from 11 Edible Fruits and Vegetables. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5186.

- Pérez-bermúdez, P.; Blesa, J.; Miguel, J.; Marcilla, A. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Extracellular Vesicles in Food: Experimental Evidence of Their Secretion in Grape Fruits. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 98, 40–50.

- Teng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Sayed, M.; Park, J.W.; Egilmez, N.K.; Zhang, H.; Teng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Sayed, M.; Hu, X.; et al. Plant-Derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Shape the Gut Plant-Derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Shape the Gut Microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 637–652.e8.

- Ren, X.; Tong, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Ye, C.; Wu, N.; Xiong, X.; Wang, J.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. MiR155-5p in Adventitial Fibroblasts-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibits Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation via Suppressing Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Expression. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1698795.

- Hong, C.S.; Jeong, E.; Boyiadzis, M.; Whiteside, T.L. Increased Small Extracellular Vesicle Secretion after Chemotherapy via Upregulation of Cholesterol Metabolism in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1800979.

- Dhondt, B.; Rousseau, Q.; De Wever, O.; Hendrix, A. Function of Extracellular Vesicle-Associated MiRNAs in Metastasis. Cell Tissue Res. 2016, 365, 621–641.

- Kranich, J.; Chlis, N.; Rausch, L.; Latha, A.; Kurz, T.; Kia, A.F.; Simons, M.; Theis, J.; Brocker, T.; Kranich, J.; et al. In Vivo Identification of Apoptotic and Extracellular Vesicle-Bound Live Cells Using Image-Based Deep Learning. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1792683.

- Huang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Turchinovich, A.; Mahairaki, V.; Troncoso, C.; Pletniková, O.; Haughey, N.J.; Vella, L.J.; Andrew, F.; Zheng, L.; et al. Influence of Species and Processing Parameters on Recovery and Content of Brain Tissue-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1785746.

- András, I.E.; Toborek, M. Extracellular Vesicles of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4.

- Melnik, B.C.; Schmitz, G. Exosomes of Pasteurized Milk: Potential Pathogens of Western Diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 3.

- Galley, D.; Besner, G.E. The Therapeutic Potential of Breast Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Nutrients 2020, 12, 745.

- Mirza, A.H.; Kaur, S.; Nielsen, L.B.; Størling, J. Breast Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Enriched in Exosomes from Mothers With Type 1 Diabetes Contain Aberrant Levels of MicroRNAs. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1–10.

- Van Herwijnen, M.J.C.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Snoek, B.L.; Kroon, A.M.T.; Kleinjan, M.; Jorritsma, R.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Hoen, E.N.M.N.; Wauben, M.H.M. Abundantly Present MiRNAs in Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Conserved Between Mammals. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 1–6.

- Somiya, M.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ochiya, T. Biocompatibility of Highly Purified Bovine Milk- Derived Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1440132.

- Burke, J.; Kolhe, R.; Hunter, M.; Isales, C.; Hamrick, M.; Fulzele, S. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: A Potential Alternative Therapeutic Agent in Orthopaedics. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 5–8.

- Cianciaruso, C.; Phelps, E.A.; Pasquier, M.; Hamelin, R.; Demurtas, D.; Ahmed, M.A.; Piemonti, L.; Hirosue, S.; Swartz, M.A.; De Palma, M.; et al. Primary Human and Rat b -Cells Release the Intracellular Autoantigens GAD65, IA-2, and Proinsulin in Exosomes Together With Cytokine- Induced Enhancers of Immunity. Diabetes 2017, 66, 460–473.

- Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Long, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Jin, L. Exosomal MicroRNAs in Giant Panda (Ailuropoda Melanoleuca) Breast Milk: Potential Maternal Regulators for the Development of Newborn Cubs. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3507.

- Kobayashi-Sun, J.; Yamamori, S.; Kondo, M.; Kuroda, J.; Ikegame, M.; Suzuki, N.; Kitamura, K.; Hattori, A.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kobayashi, I. Uptake of Osteoblast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Promotes the Differentiation of Osteoclasts in the Zebrafish Scale. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 190.

- Fu, B.; Ma, H.; Liu, D. Extracellular Vesicles Function as Bioactive Molecular Transmitters in the Mammalian Oviduct: An Inspiration for Optimizing in Vitro Culture Systems and Improving Delivery of Exogenous Nucleic Acids during Preimplantation Embryonic Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2189.

- Qu, P.; Luo, S.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Yuan, X.; Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, E. Extracellular Vesicles and Melatonin Benefit Embryonic Develop by Regulating Reactive Oxygen Species and 5-methylcytosine. J. Pineal Res. 2020, 68, e12635.

- Rohde, E.V.A.; Pachler, K.; Gimona, M. Manufacturing and Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles from Umbilical Cord À Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Clinical Testing. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 581–592.

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Serrano-Pertierra, E.; Oliveira-Rodríguez, M.; Zaragozá, M.C.; Martínez-Martínez, A.; Blanco-López, M.D.; Alegre, J. Circulating Extracellular Vesicles as Potential Biomarkers in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: An Exploratory Pilot Study. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1453730.

- Tao, S.C.; Guo, S.C.; Zhang, C.Q. Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: An Emerging Therapeutic Approach. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 828–834.

- Conlan, R.S.; Pisano, S.; Oliveira, M.I.; Ferrari, M.; Mendes Pinto, I. Exosomes as Reconfigurable Therapeutic Systems. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 636–650.

- Morales-kastresana, A.; Musich, T.A.; Welsh, J.A.; Demberg, T.; Wood, J.C.S.; Bigos, M.; Ross, C.D.; Kachynski, A.; Dean, A.; Felton, E.J.; et al. High-Fidelity Detection and Sorting of Nanoscale Vesicles in Viral Disease and Cancer. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1597603.

- Gu, J.; Wu, J.; Fang, D.; Qiu, Y.; Zou, X.; Jia, X.; Yin, Y.; Shen, L.; Mao, L. Exosomes Cloak the Virion to Transmit Enterovirus. Virulence 2020, 11, 32–38.

- Raab-Traub, N.; Dittmer, D.P. Viral Effects on the Content and Function of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 559–572.

- Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell 2016, 164, 1226–1232.

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, L.; Bian, H.; Hu, J.; Li, D.; Xia, C.; Xu, H. Tumor-Derived EV-Encapsulated MiR-181b-5p Induces Angiogenesis to Foster Tumorigenesis and Metastasis of ESCC. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 421–437.

- Van Niel, G.; d’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228.

- Hansen, E.P.; Fromm, B.; Andersen, S.D.; Marcilla, A.; Andersen, K.L.; Borup, A.; Williams, A.R.; Jex, A.R.; Gasser, R.B.; Young, N.D.; et al. Exploration of Extracellular Vesicles from Ascaris Suum Provides Evidence of Parasite–Host Cross Talk. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1578116.

- Hong, J.; Dauros-Singorenko, P.; Whitcombe, A.; Payne, L.; Blenkiron, C.; Phillips, A.; Swift, S. Analysis of the Escherichia Coli Extracellular Vesicle Proteome Identifies Markers of Purity and Culture Conditions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1632099.

- Sutaria, D.S.; Badawi, M.; Phelps, M.A.; Schmittgen, T.D. Achieving the Promise of Therapeutic Extracellular Vesicles: The Devil Is in Details of Therapeutic Loading. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 1053–1066.

- Yuan, T.; Huang, X.; Woodcock, M.; Du, M.; Dittmar, R.; Wang, Y.; Tsai, S.; Kohli, M.; Boardman, L.; Patel, T.; et al. Plasma Extracellular RNA Profiles in Healthy and Cancer Patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19413.

- Zaborowski, M.P.; Lee, K.; Na, Y.J.; Sammarco, A.; Zhang, X.; Iwanicki, M.; Cheah, P.S.; Lin, H.-Y.; Zinter, M.; Chou, C.-Y.; et al. Methods for Systematic Identification of Membrane Proteins for Specific Capture of Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 255–268.e6.

- Jang, S.C.; Crescitelli, R.; Cvjetkovic, A.; Belgrano, V.; Olofsson Bagge, R.; Sundfeldt, K.; Ochiya, T.; Kalluri, R.; Lötvall, J. Mitochondrial Protein Enriched Extracellular Vesicles Discovered in Human Melanoma Tissues Can Be Detected in Patient Plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1635420.

- Wei, P.; Wu, F.; Kang, B.; Sun, X.; Heskia, F.; Pachot, A.; Liang, J.; Li, D. Plasma Extracellular Vesicles Detected by Single Molecule Array Technology as a Liquid Biopsy for Colorectal Cancer. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1809765.

- Choi, D.-S.; Choi, D.-Y.; Hong, B.; Jang, S.; Kim, D.-K.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.-K.; Pyo Kim, K.; Gho, Y. Quantitative Proteomics of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Human Primary and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2012, 1, 18704.

- Kalluri, R. The Biology and Function of Urine Exosomes in Bladder Cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 4, 2362.

- Yuana, Y.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Extracellular Vesicles in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Blood Rev. 2013, 27, 31–39.

- Meldolesi, J. Extracellular Vesicles, News about Their Role in Immune Cells: Physiology, Pathology and Diseases. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2019, 196, 318–327.

- Zheng, X.; Xu, K.; Zhou, B.; Chen, T.; Huang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wen, F.; Ge, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, S.; et al. A Circulating Extracellular Vesicles-Based Novel Screening Tool for Colorectal Cancer Revealed by Shotgun and Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1750202.

- Luo, P.; Mao, K.; Xu, J.; Wu, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, M.; Duan, L.; Tan, Q.; Ma, G.; et al. Metabolic Characteristics of Large and Small Extracellular Vesicles from Pleural Effusion Reveal Biomarker Candidates for the Diagnosis of Tuberculosis and Malignancy. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1790158.

- Sundar, I.K.; Li, D.; Rahman, I.; Sundar, I.K. Small RNA-Sequence Analysis of Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicle MiRNAs in Smokers and Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease as Circulating Biomarkers. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1684816.

- Cheng, L.; Vella, L.J.; Barnham, K.J.; McLean, C.; Masters, C.L.; Hill, A.F. Small RNA Fingerprinting of Alzheimer’s Disease Frontal Cortex Extracellular Vesicles and Their Comparison with Peripheral Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1766822.

- Lane, R.E.; Korbie, D.; Hill, M.M.; Trau, M. Extracellular Vesicles as Circulating Cancer Biomarkers: Opportunities and Challenges. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 14.

- Popowski, K.; Lutz, H.; Hu, S.; George, A.; George, A. Exosome Therapeutics for Lung Regenerative Medicine. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1785161.

- García-manrique, P.; Matos, M.; Gutiérrez, G.; Pazos, C.; Blanco-lópez, M.C.; Pazos, C. Therapeutic Biomaterials Based on Extracellular Vesicles: Classification of Bio-Engineering and Mimetic Preparation Routes. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1422676.

- Upadhya, R.; Madhu, L.N.; Attaluri, S.; Leite, D.; Gitaí, G.; Pinson, M.R.; Kodali, M.; Shetty, G.; Kumar, S.; Shuai, B.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Human IPSC-Derived Neural Stem Cells: MiRNA and Protein Signatures, and Anti-Inflammatory and Neurogenic Properties. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1809064.

- Wen, C.; Seeger, R.C.; Fabbri, M.; Wang, L.; Wayne, A.S.; Jong, A.Y. Biological Roles and Potential Applications of Immune Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1400370.

- Conzelmann, C.; Groß, R.; Zou, M.; Krüger, F.; Görgens, A.; Gustafsson, M.O.; El Andaloussi, S.; Münch, J.; Müller, J.A. Salivary Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Zika Virus but Not SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1808281.

- Koliha, N.; Wiencek, Y.; Heider, U.; Jüngst, C.; Kladt, N.; Krauthäuser, S.; Johnston, I.C.D.; Bosio, A.; Schauss, A.; Wild, S. A Novel Multiplex Bead-Based Platform Highlights the Diversity of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2016, 5, 29975.

- Alfieri, M.; Leone, A.; Ambrosone, A. Plant-Derived Nano and Microvesicles for Human Health and Therapeutic Potential in Nanomedicine. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 498.

- Ito, Y.; Taniguchi, K.; Kuranaga, Y.; Eid, N.; Inomata, Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Uchiyama, K. Uptake of MicroRNAs from Exosome-Like Nanovesicles of Edible Plant Juice by Rat Enterocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3749.

- Foo, J.B.; Looi, Q.H.; Chong, P.P.; Hassan, N.H.; Yeo, G.E.C.; Ng, C.Y.; Koh, B.; How, C.W.; Lee, S.H.; Law, J.X. Comparing the Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells and Their Secretory Products in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 2616807.

- Ferguson, S.W.; Nguyen, J. Exosomes as Therapeutics: The Implications of Molecular Composition and Exosomal Heterogeneity. J. Control. Release 2016, 228, 179–190.

- Takakura, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Takahashi, Y. Therapeutic Application of Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs): Pharmaceutical and Pharmacokinetic Challenges. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 43, 576–583.

- Goyal, G.; Phukan, A.C.; Hussain, M.; Lal, V.; Modi, M.; Goyal, M.K.; Sehgal, R. Sorting out Difficulties in Immunological Diagnosis of Neurocysticercosis: Development and Assessment of Real Time Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification of Cysticercal DNA in Blood. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 408, 116544.

- Oskouie, M.N.; Aghili Moghaddam, N.S.; Butler, A.E.; Zamani, P.; Sahebkar, A. Therapeutic Use of Curcumin-Encapsulated and Curcumin-Primed Exosomes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8182–8191.

- Bei, Y.; Xu, T.; Lv, D.; Yu, P.; Xu, J.; Che, L.; Das, A.; Tigges, J.; Toxavidis, V.; Ghiran, I.; et al. Exercise-Induced Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Protect against Cardiac Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 38.

- Kalarikkal, S.P.; Prasad, D.; Kasiappan, R.; Chaudhari, S.R.; Sundaram, G.M. A Cost-Effective Polyethylene Glycol-Based Method for the Isolation of Functional Edible Nanoparticles from Ginger Rhizomes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4456.

- Saint-Pol, J.; Gosselet, F.; Duban-Deweer, S.; Pottiez, G.; Karamanos, Y. Targeting and Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier with Extracellular Vesicles. Cells 2020, 9, 851.