Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belen Congregado | -- | 2432 | 2022-07-04 19:58:32 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2432 | 2022-07-06 02:26:03 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Congregado, B.; Rivero, I.; Osmán, I.; Sáez, C.; López, R.M. PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24802 (accessed on 11 March 2026).

Congregado B, Rivero I, Osmán I, Sáez C, López RM. PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24802. Accessed March 11, 2026.

Congregado, Belén, Inés Rivero, Ignacio Osmán, Carmen Sáez, Rafael Medina López. "PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24802 (accessed March 11, 2026).

Congregado, B., Rivero, I., Osmán, I., Sáez, C., & López, R.M. (2022, July 04). PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24802

Congregado, Belén, et al. "PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

The introduction of PARP inhibitors (PARPi) in prostate cancer is a milestone and provides a pathway to hope in fighting this disease. It is the first time that drugs, based on the concept of synthetic lethality, have been approved for prostate cancer. In addition, it is also the first time that genetic mutation tests have been included in the therapeutic algorithm of this disease, representing a significant step forward for precision and personalized treatment of prostate cancer.

prostate cancer

PARP inhibitors

mutation test 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common tumor diagnosed in men in the Western World, the third leading cause of cancer death in Europe, and the second in the United States [1][2]. Fortunately, most PCa are diagnosed at their very early stages and can be cured with radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy. However, more than 5% of patients are diagnosed with metastatic disease, and 30–40% of patients will develop biochemical recurrence after treatment intended to cure. A considerable proportion of them will develop metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), a condition that leads to death in a short period of time [3]. PCa can be defined as a heterogeneous condition, which ranges from a relatively indolent to an aggressive disease. Primary PCa is characterized by heterogeneity. The disease is often multifocal, and distinct foci can arise as clonally separate lesions with little or no shared driver gene alterations. In contrast, the metastatic foci of PCa seem to arise from a single clone and manifest subclonal homogeneity [4].

Androgen receptor (AR) signaling plays a central role in the disease’s development; therefore, chemical castration, or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), remains the mainstay of systemic treatment [5]. Several mechanisms try to explain resistance to this therapy, such as androgen receptor (AR) gain-of-function mutations or splice variants (e.g., AR-V7), loss of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., p53, pTEN), and modifications of stromal components into the tumor microenvironment, promoting invasion, neoangiogenesis, and the metastatization process [6].

In recent decades, a large number of novel drugs with different mechanisms of action have been introduced in the therapeutic management against prostate cancer in all stages, focusing mainly on metastatic and castration-resistant disease, with and without metastasis, where they have shown to delay progression and prolong survival. Clinical options include cytostatic agents (docetaxel plus prednisone, cabacitaxel), second-generation antiandrogens, (abiraterone, enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide) bone-targeted therapies (Radium 223), immunotherapy (sipuleucel-T), Akt inhibitors, and radioisotopes (Lutetium-177–PSMA-617). However, there is a lack of high-quality randomized trials exploring different treatment sequences.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for more effective treatments for patients with mCRPC, especially those who have progressed after novel hormonal therapies and taxane chemotherapies.

In the last two years, two poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (Olaparib and Rucaparib) have been approved for mCPRC, opening a new horizon in the treatment of PCa [7]. Olaparib was approved for mCRPC patients with any Homologous Recombination (HR) mutation who had previously received a second-generation hormonal agent, and rucaparib was approved for mCRPC patients with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation who had previously received both a second-generation hormonal agent and a taxane chemotherapy.

The rationale for the use of PARP inhibitors (PARPi) is mainly based on the high frequency of genetic mutations found in PCa and the interesting phenomenon of synthetic lethality. Genetic alterations in PCa include germline and somatic mutations. Germline mutations affect all cells of the body and may be useful for genetic counseling. Somatic alterations occur only in tumor cells and may evolve due to intrinsic genome instability within the tumor and clonal selection resulting from earlier therapies. Germline mutations in Homologous Recombination (HR) DNA repair genes have been observed in approximately 10–15% of patients with metastatic PCa, while somatic mutations occur in 20–25% of those patients, with BRCA2 and ATM being the most frequently mutated. Moreover, compared to locoregional tumors, mCRPC presents a higher frequency of aberrations in the AR, TP53, RB1, and PTEN genes [8]. This evidence supports the research of PARPi in CPRCm. Nevertheless, these genetic alterations have also been described in localized disease, conferring a more aggressive evolution. Therefore, research with PARPi is being extended to earlier stages of the disease.

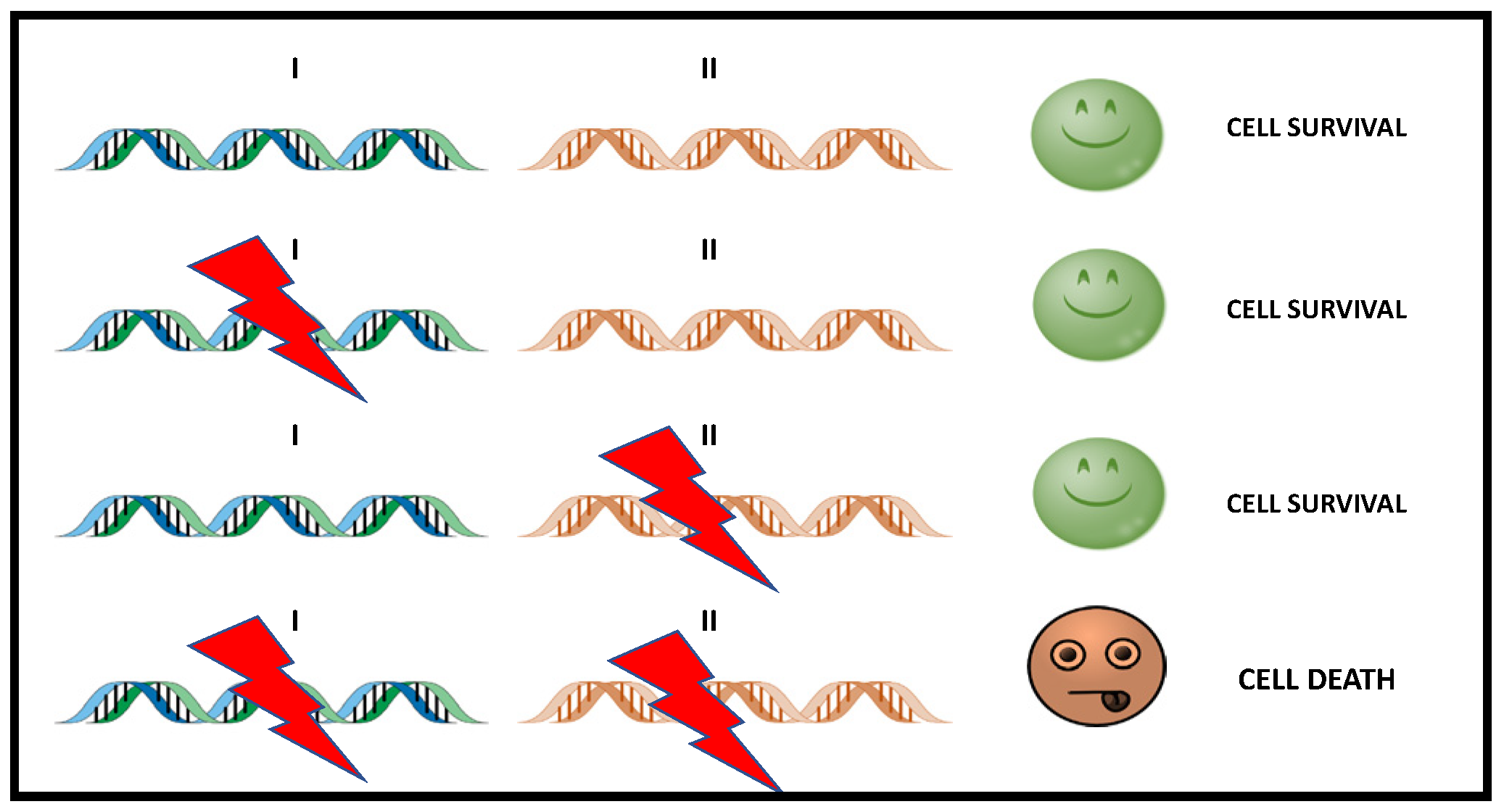

Synthetic lethality is a genetic concept in which the functional loss of two genes results in cell death, while the functional loss of only one of them is compatible with cell viability (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simple scheme of Synthetic Lethality. The alteration of either gene alone (gen I or gen II) does not causes cell death, while the simultaneous alteration of two genes triggers cell death. In cancer treatment, gene II becomes a therapeutic target that can be used to attack tumor cells with dysfunction in I.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes involved in transcriptional regulation and repair of double-strand DNA damage breaks (DSBs) in the DNA molecule, playing a key role on the HR path. Cells with loss-of-function in these genes are unable to repair errors in DNA, depending on the ability of PARP to activate alternative routes. Since they depend on PARPs to maintain genome integrity, these cells are highly vulnerable to PARPi.

2. Rationale of Use of PARP Inhibitors in PCa

2.1. DNA Repair Pathway

The integrity of DNA is continuously challenged by a variety of agents and processes that can alter, directly or indirectly, the sequence of this molecule. Damage that arises in DNA, its repair, or its absence are key factors in the appearance of mutations that initiate and promote tumorigenesis [9].

Given the potentially devastating effect of these types of mutations, the healthy cells evolved to defend themselves from the deleterious effects that DNA damage causes through several molecular pathways, which, as a whole, are called DNA Damage Response (DDR). These pathways have the ability to identify the damage, promote the arrest of the cell cycle, and, ultimately, proceed with its repair, contributing to the maintenance of genome integrity.

DDR can be divided into distinct but functionally interconnected means that process the repair of existing damage: first, the repair of double-strand DNA damage breaks (DSB), which includes repair by Homologous Recombination (HR) and nonhomologous recombination; second, the repair of single-strand breaks (SSB), of which the excision repair base (ERB) is a part. Several key proteins contribute to the correct function of these processes. The BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, ATM, CHEK1, CHEK2, and RAD51 play a role in the HR process. However, Poly enzymes (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 and 2 (PARP1 and PARP2) are the pillars of the ERB process [10].

Those proteins also play a key role in the repair of DSB by facilitating the activation of the repair by HR and contributing to the inhibition of less conservative repair pathways, such as the nonhomologous route end joining (NHEJ). Thus, the absence of PARPs contributes to the dysfunctional HR process, making nonconservative DNA repair processes the dominant pathways [11].

2.2. Role of DNA Damage Repair Genes in Prostate Cancer

2.2.1. DDR Mutations in Prostate Cancer

Classical studies show that germline mutations in HR DNA repair genes have been observed in approximately 10–15% of patients with metastatic prostate cancer, while somatic mutations occur in 20–25% of those patients [12][13].

Of these mutations, BRCA2 mutations are the most frequently found (12–18%), while ATM (3–6%), CHEK2 (2–5%), and BRCA1 (<2%) are other commonly altered genes involved in HRR [14][15].

Since DDR pathway alterations were seen at similar rates between localized and metastatic PCa, it has been speculated that PARPi may also have a therapeutic effect in localized PCa.

To support this hypothesis, a 2019 study by Kim et al. [16] analyzed the DDR pathway alterations in localized PCa using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) public database. Their results highlighted that the DDR alteration rate was surprisingly higher than suggested by previous studies [17][18] and was associated with shorter OS in men with postoperative HR features.

A systematic review of the p`revalence of DNA-damage-response gene mutations in prostate cancer that summarizes the prevalence of DDR mutation carriers in the unselected (general) PCa and familiar PCa populations confirms these findings [19].

BRCA1/2 genes are located at chromosomes 17q21 and 13q12, respectively. They are large genes consisting of 100 and 70 kb, respectively. They have an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance.

2.2.2. Germline Mutations

Multiple studies have reported an association between frequent germline deleterious mutations in DDR genes and advanced PCa. Specifically, germline BRCA1/2 mutations are associated with increased risk and more aggressive PCa, higher risk of nodal involvement, and distant metastasis at diagnosis [20].

Germline BRCA2 mutations increase the risk of developing PCa eightfold at the age of 65 years [21]. In the localized disease, germline BRCA1/2 mutations are related with progression in patients undergoing active surveillance and a high rate of recurrence in patients treated with curative intention [22][23]. Similarly, in the metastatic setting, it is associated with a more aggressive evolution [24].

The prevalence of germline mutations varies among countries and ethnic groups.

The International Stand Up to Cancer/Prostate Cancer Foundation team (SU2C-PCF) studied 150 metastatic PCa identifying 8% of germline and 23% of somatic DDR mutations [12]. BRCA2 was the most frequent mutation (13%), followed by ATM (7.3%), MSH2 (2%), and BRCA1, FANCA, MLH1, RAD51B, and RAD51C.

Pritchard et al. studied germline mutations in 692 men with mCRPC with no family history, identifying 84 deleterious mutations in the 20 DNA repair genes studied in 82 men (11.8%), being BRCA2 the most frequent one (5.3%) [13].

Nicolosi et al. analyzed 3607 men with PCa [25], finding germline mutations in 620 of them (17.2%), of which 30.7% were BRCA1/2 mutations; other mutations included ATM, PALB2, CHEK2, and mismatch repair genes PMS2 and MLH1/2/6.

2.2.3. Somatic Mutations

Somatic mutations also stimulate carcinogenesis [26]. As explained before, Robinson et al. found that 23% of mCRPC had somatic mutations in DNA repair pathway genes, with most mutations in BRCA2 and ATM [10]. Different studies have found 12% and 8% of PCa patients carrying a BRCA1/2 or ATM mutation, respectively, and more frequently in mCRPC [27]. Abida et al. observed somatic BRCA2 mutations in tumors before they progressed to metastatic disease. Somatic BRCA2 mutations have been suggested to arise early in tumors from patients who eventually develop metastatic disease, while ATM alterations seem to enrich in CRPC [15].

2.3. Mechanism of Action of PARP Inhibitors

The original rationale for using PARPi as a cancer treatment is that PARPi can sensitize tumor cells to therapies that cause DNA damage, such as chemo or radiotherapy. The inhibition of PARP-mediated repair of DNA damage produced by chemotherapy or radiotherapy, may result in an increased of therapeutic potency [28].

Almost two decades ago, two groups described the important concept of Synthetic Lethal (SL) interaction between PARP inhibition and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, which represented a new therapeutic option for BRCA-mutant tumors [29][30].

SL means that a defect in either one of two genes has little effect on the organism, but a combination of defects in both genes results in cell death.

Carriers of deleterious heterozygous germline mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have high risk of different types of cancer, such as PCa [31]. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor-suppressor genes involved in transcriptional regulation and, as stated before, are critical to the repair of DSBs in the DNA molecule, playing a key role in the HR pathway [30]. Cells with functional loss in these genes are unable to repair errors in DNA, depending on PARPs ability to detect these damages and activate alternative repair pathways.

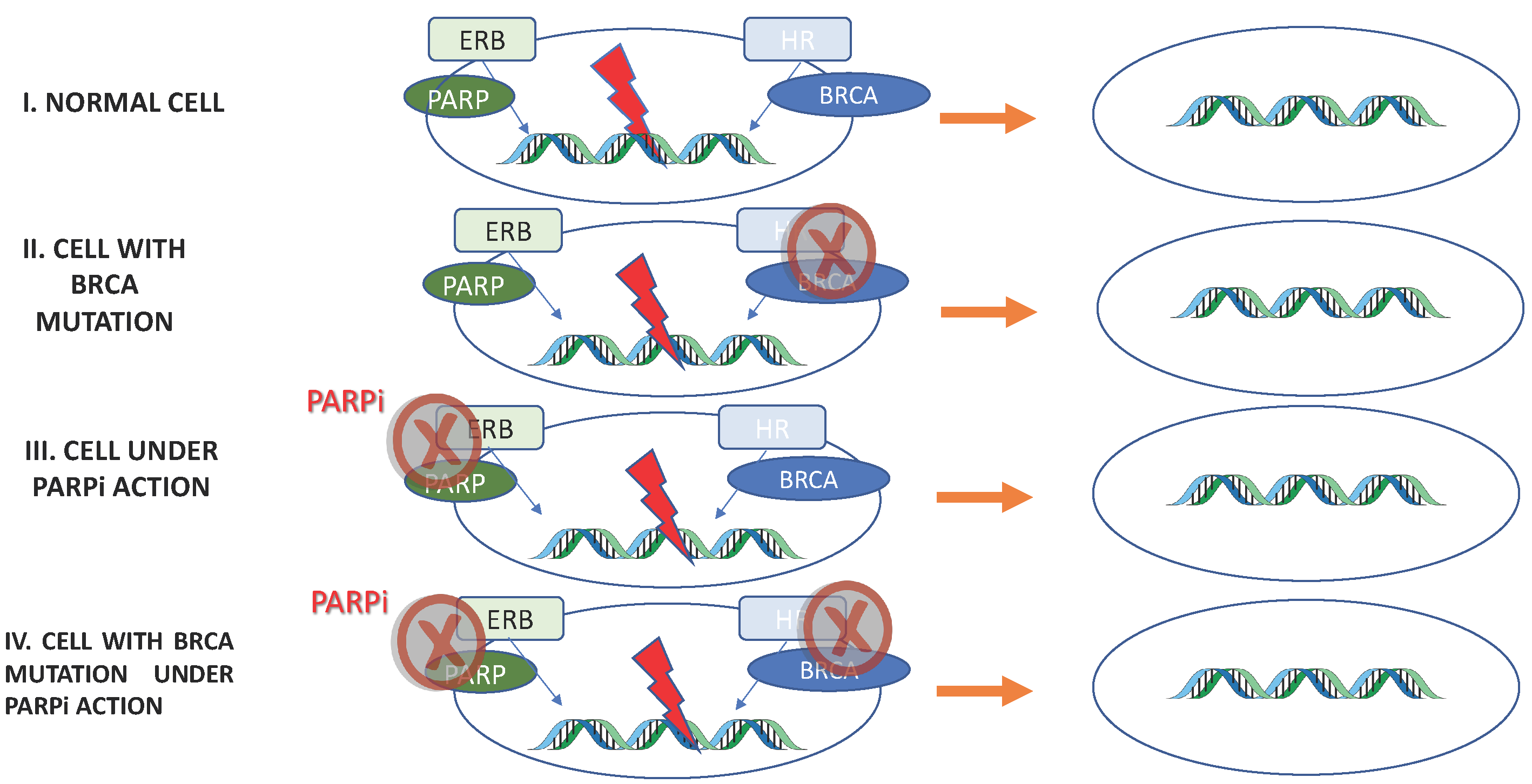

By depending on PARPs to maintain genome integrity, these cells are highly vulnerable to PARPi. Although the functional loss of only one of the genes is tolerated (BRCA or PARP), the inhibition of PARP in cells with BRCA mutations makes them unable to repair DNA damage, causing the accumulation of errors and, ultimately, leading to cell death (synthetic lethality) [10].

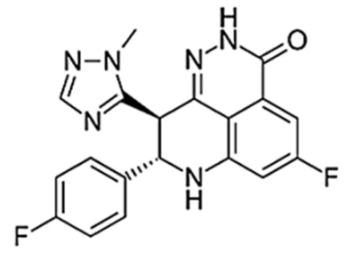

PARPi antitumor activity is based on the concept of synthetic lethality, in which two separate molecular pathways, which are not lethal when disrupted individually, cause cell death when inhibited simultaneously (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PARPi antitumor activity based on Synthetic Lethality. I: Normal cell. Excision repair base (ERB) and homologous recombination (HR) are functional: repair DNA maintaining cell viability. II, III: Through BRCA mutation or PARPi, one of the repair pathway’s is inhibited. Once the other pathway is functional, the cell maintains its viability. IV: Both DNA repair pathways are inhibited; therefore, errors in the DNA are not repaired, resulting in cell death.

The demonstration that BRCA-mutant tumor cells were as much as 1000 times more sensitive to PARPi than BRCA-wild type cells provided the impetus for PARPi to be tested in clinical trials as single agents. PARPi were the first clinically approved drugs to explore the SL mechanism [32]. This concept has been reviewed, since it has been shown that some PARPi “trap” PARP1 on DNA, preventing autoPARylation and PARP1 release from the site of damage, thereby interfering with the catalytic cycle of PARP1 [33][34][35].

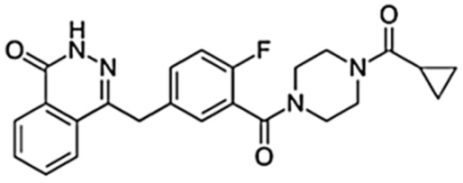

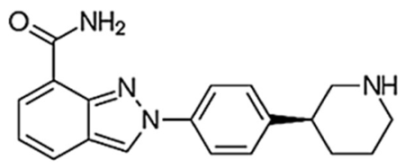

PARPi differ in their capacity to trap PARP1; talazoparib is nearly 100 times more potent than niraparib, followed by olaparib and rucaparib. However, veliparib has a low ability to trap PARP1. These differences in PARP1 trapping are a predictor of in vitro cytotoxicity in BRCA mutant cells, being talazoparib the one with more cytotoxic capacity [34] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. PARPi Trapping Potency.

This different trapping capacity is also important when combined therapies are studied, since a high trapping activity could be accompanied by high toxicity.

Initially, it was postulated that PARPi would only be effective in tumors with mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes. However, in more recent clinical studies, it was found that tumors without BRCA1/2 mutations might respond to this treatment, although its benefits are less significant [36][37].

The “trapping” effect of PARPi can also have a direct cytotoxic effect: PARPi will trap PARP proteins to the ssDNA damage sites, preventing its release, which is essential for mediator proteins to initiate repair. The trapped PARP proteins will cause replication fork stalling, which will increase replication stress and eventually cause cell death [38].

Therefore, based on these observations, the number of patients who could theoretically benefit from PARPi has been widely extended. PARPi can be used as monotherapy or in association with other drugs, namely in combination with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and other targeted therapies that limit DNA damage repair. The combination of drugs has a synergistic and advantageous effect, to the extent that it makes it possible to overcome the resistance to PARPi and increase the effectiveness of these drugs [39].

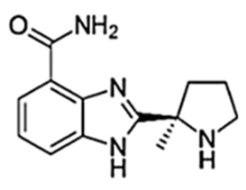

Table 1 represents the chemical structures and pharmacological properties of the currently available PARP inhibitors (PARPi).

Table 1. Chemical structures and pharmacological properties of the currently available PARP inhibitors (PARPi).

| Structural Formula | Dose [mg] | Cmax [ng/mL] | Tmax [h] | Half-Life [h] | PARP1 Trapping Ability | Direct Off-Targets | Indirect Off-Targets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olaparib (AZD-2281, MK-7339) |  |

300/12 h | 7700 | 1.5 | 14.9 | Moderate | PARP1, PARP2, PARP3 | |

| Rucaparib (AG014699) |  |

600/12 h | 1940 | 1.9 | 25.9 | Moderate | ARTD5, ARTD6, PARP1,2,3 TNKS1, TNKS2 | ALDH2, H6PD, CDK16, PIM3, DYRK1B |

| Niraparib (MK-4827) |  |

300/24 h | 2232 | 3.0 | 36 | Moderate–high | PARP2, PARP3, PARP4, PARP12 | ALDH2, CIT, DCK, DYRK1A, DYRK1B |

| Talazoparib (BMN-673) |  |

1/24 h | 16.4 | 1–2 | 90 | Very high | PARP2 PARP1 |

|

| Veliparib (ABT-888) |  |

40/12 h | 410 | 1.0 | 6 | Very low | PARP2, PARP3, PARP10 |

References

- Dyba, T.; Randi, G.; Bray, F.; Martos, C.; Giusti, F.; Nicholson, N.; Gavin, A.; Flego, M.; Neamtiu, L.; Dimitrova, N.; et al. The European cancer burden in 2020: Incidence and mortality estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 157, 308–347.

- Siegel, R.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. ACS J. 2022, 72, 7–33.

- Mottet, N.; Van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Expert Patient Advocate (European Prostate Cancer Coalition/Europa UOMO); De Santis, M.; Gillessen, S.; Grummet, J.; Henry, A.M.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Lam, T.B.; et al. AU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer 2022. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Haffner, M.C.; Zwart, W.; Roudier, M.P.; True, L.D.; Nelson, W.G.; Epstein, J.I.; De Marzo, A.M.; Nelson, P.S.; Yegnasubramanian, S. Genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 79–92.

- Tan, M.H.E.; Li, J.; Xu, H.E.; Melcher, K.; Yong, E.-L. Androgen receptor: Structure, role in prostate cancer and drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 3–23.

- Mollica, V.; Di Nunno, V.; Cimadamore, A.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cheng, L.; Santoni, M.; Scarpelli, M.; Montironi, R.; Massari, F. Molecular Mechanisms Related to Hormone Inhibition Resistance in Prostate Cancer. Cells 2019, 8, 43.

- Leung, D.K.W.; Chiu, P.K.F.; Ng, C.-F.; Teoh, J.Y.C. Novel Strategies for Treating Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 339.

- Cheng, H.H.; Sokolova, A.O.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Small, E.J.; Higano, C.S. Germline and Somatic Mutations in Prostate Cancer for the Clinician. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 515–521.

- Lord, C.J.; Ashworth, A. The DNA damage response and cancer therapy. Nature 2012, 481, 287–294.

- Lord, C.J.; Ashworth, A. PARP inhibitors: The First Synthetic Lethal Targeted Therapy. Science 2017, 355, 1152–1158.

- Mirza, M.; Pignata, S.; Ledermann, J. Latest clinical evidence and further development of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1366–1376.

- Robinson, D.; Van Allen, E.M.; Wu, Y.M.; Schultz, N.; Lonigro, R.J.; Mosquera, J.; Montgomery, B.; Taplin, M.; Pritchard, C.C.; Attard, G.; et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 2015, 161, 1215.

- Pritchard, C.C.; Mateo, J.; Walsh, M.F.; De Sarkar, N.; Abida, W.; Beltran, H.; Garofalo, A.; Gulati, R.; Carreira, S.; Eeles, R.; et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 443–453.

- Nombela, P.; Lozano, R.; Aytes, A.; Mateo, J.; Olmos, D.; Castro, E. BRCA2 and Other DDR Genes in Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 352.

- Abida, W.; Armenia, J.; Gopalan, A.; Brennan, R.; Walsh, M.; Barron, D.; Danila, D.; Rathkopf, D.; Morris, M.; Slovin, S.; et al. Prospective Genomic Profiling of Prostate Cancer Across Disease States Reveals Germline and Somatic Alterations That May Affect Clinical Decision Making. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 1–32.

- Kim, E., Jr.; Kim, S.; Srivastava, A.; Saraiya, B.; Mayer, T.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, I.Y. Similar Incidence of DNA Damage Response Pathway Alterations Between Clinically Localized and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. BMC Urol. 2019, 19, 33.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell 2015, 163, 1011–1025.

- Marshall, C.H.; Fu, W.; Wang, H.; Baras, A.S.; Lotan, T.; Antonarakis, E.S. Prevalence of DNA repair gene mutations in localized prostate cancer according to clinical and pathologic features: Association of Gleason score and tumor stage. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019, 22, 59–65.

- Lang, S.H.; Swift, S.L.; White, H.; Misso, K.; Kleijnen, J.; Quek, R.G. A systematic review of the prevalence of DNA damage response gene mutations in prostate cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 55, 597–616.

- Castro, E.; Goh, C.; Olmos, D.; Saunders, E.; Leongamornlert, D.; Tymrakiewicz, M.; Mahmud, N.; Dadaev, T.; Govindasami, K.; Guy, M.; et al. Germline BRCA mutations are associated with higher risk of nodal involvement, distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1748–1757.

- Kote-Jarai, Z.; Leongamornlert, D.; Saunders, E.; Tymrakiewicz, M.; Castro, E.; Mahmud, N.; Guy, M.; Edwards, S.; O’Brien, L.; Sawyer, E.; et al. BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: Implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 1230–1234.

- Carter, H.B.; Helfand, B.; Mamawala, M.; Wu, Y.; Landis, P.; Yu, H.; Wiley, K.; Na, R.; Shi, Z.; Petkewicz, J.; et al. Germline mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 are associated with grade reclassification in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019, 75, 743–749.

- Castro, E.; Goh, C.; Leongamornlert, D.; Saunders, E.; Tymrakiewicz, M.; Dadaev, T.; Govindasami, K.; Guy, M.; Ellis, S.; Frost, D.; et al. Effect of BRCA Mutations on Metastatic Relapse and Cause-specific Survival After Radical Treatment for Localised Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 186–193.

- Castro, E.; Romero-Laorden, N.; Del Pozo, A.; Lozano, R.; Medina, A.; Puente, J.; Piulats, J.M.; Lorente, D.; Saez, M.I.; Morales-Barrera, R.; et al. PROREPAIR-B: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Impact of Germline DNA Repair Mutations on the Outcomes of Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 490–503.

- Nicolosi, P.; Ledet, E.; Yang, S.; Michalski, S.; Freschi, B.; O’Leary, E.; Esplin, E.D.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Sartor, O. Prevalence of Germline Variants in Prostate Cancer and Implications for Current Genetic Testing Guidelines. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 523–528.

- Koochekpour, S. Genetic and Epigenetic Changes in Human Prostate Cancer. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2011, 13, 80–98.

- Beltran, H.; Yelensky, R.; Frampton, G.; Park, K.; Downing, S.R.; MacDonald, T.Y.; Jarosz, M.; Lipson, D.; Tagawa, S.T.; Nanus, D.M.; et al. Targeted Next-generation Sequencing of Advanced Prostate Cancer Identifies Potential Therapeutic Targets and Disease Heterogeneity. Eur. Urol. 2012, 63, 920–926.

- Bramco, C.; Joana Paredes, J. PARP Inhibitors: From the Mechanism of Action to Clinical Practice. Acta Med. Port. 2022, 35, 135–143.

- Farmer, H.; McCabe, N.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.N.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Richardson, T.B.; Santarosa, M.; Dillon, K.J.; Hickson, I.; Knights, C.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921.

- Bryant, H.E.; Schultz, N.; Thomas, H.D.; Parker, K.M.; Flower, D.; Lopez, E.; Kyle, S.; Meuth, M.; Curtin, N.J.; Helleday, T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005, 434, 913–917.

- King, M.C. “The race” to clone BRCA1. Science 2014, 343, 462–1465.

- Ashworth, A.; Lord, C.J.; Reis-Filho, J.S. Genetic Interactions in Cancer Progression and Treatment. Cell 2011, 145, 30–38.

- Murai, J.; Huang, S.-Y.N.; Das, B.B.; Renaud, A.; Zhang, Y.; Doroshow, J.H.; Ji, J.; Takeda, S.; Pommier, Y. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5588–5599.

- Murai, J.; Huang, S.-Y.N.; Renaud, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J.; Takeda, S.; Morris, J.; Teicher, B.; Doroshow, J.H.; Pommier, Y. Stereospecific PARP Trapping by BMN 673 and Comparison with Olaparib and Rucaparib. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 433–443.

- Pommier, Y.; O’Connor, M.J.; de Bono, J. Laying a trap to kill cancer cells: PARP inhibitors and their mechanisms of action. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 362–379.

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I.; et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2154–2164.

- González-Martín, A.; Pothuri, B.; Vergote, I.; DePont Christensen, R.; Graybill, W.; Mirza, M.R.; McCormick, C.; Lorusso, D.; Hoskins, P.; Freyer, G.; et al. Niraparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2391–2402.

- Díaz-Mejía, N.; García-Illescas, D.; Morales-Barrera, R.; Suarez, C.; Planas, J.; Maldonado, X.; Carles, J.; Mateo, J. PARP inhibitors in advanced prostate cancer: When to use them? Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2021, 28, 79–93.

- Yi, M.; Dong, B.; Qin, S.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K.; Luo, S. Advances and perspectives of PARP inhibitors. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 8, 29–41.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

622

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No