Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sayed Saghaian | -- | 2613 | 2022-06-27 12:58:15 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | -134 word(s) | 2479 | 2022-06-28 03:10:01 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Saghaian, S.; Ajibade, A. U.S. Almond Exports and Retaliatory Trade Tariffs. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24510 (accessed on 08 January 2026).

Saghaian S, Ajibade A. U.S. Almond Exports and Retaliatory Trade Tariffs. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24510. Accessed January 08, 2026.

Saghaian, Sayed, Abraham Ajibade. "U.S. Almond Exports and Retaliatory Trade Tariffs" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24510 (accessed January 08, 2026).

Saghaian, S., & Ajibade, A. (2022, June 27). U.S. Almond Exports and Retaliatory Trade Tariffs. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24510

Saghaian, Sayed and Abraham Ajibade. "U.S. Almond Exports and Retaliatory Trade Tariffs." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

U.S. almond exports have market concentration and strong market power in international markets. The efforts toward more sustainable production of almonds to solidify an already established market share in the world almond markets and against substitutes, such as pistachios, seem to be a sound strategy and focus of the U.S. almond agribusinesses and exporters.

almond nuts

export demand

retaliatory tariff policy

1. Introduction

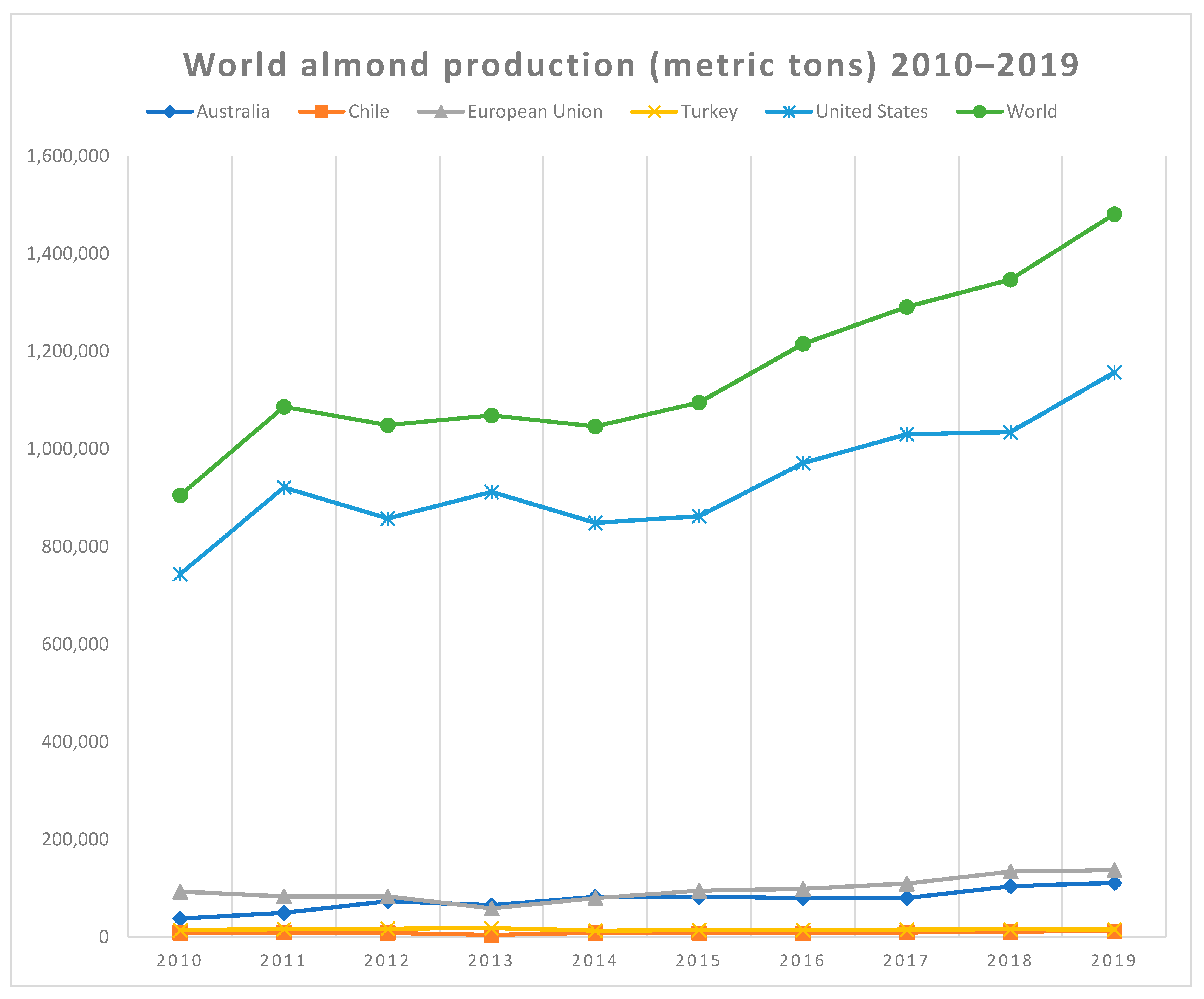

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the United States (U.S.) dominates the world’s almond market as a top producer, consumer, and exporter [1]. The U.S. has a competitive advantage in tree nut production and exports and is well-positioned to maintain its global dominance over time. Since the 1980s, the U.S. is the number one producer of almonds globally (Figure 1). Other notable producers are Australia, Chile, Spain, and Italy [1]. Almond production has rapidly outpaced other U.S. tree nuts, such as walnuts, pistachios, pecans, and hazelnuts.

Figure 1. World almond production (in metric tons) 2010–2019. Source: USDA, Foreign Agricultural Service.

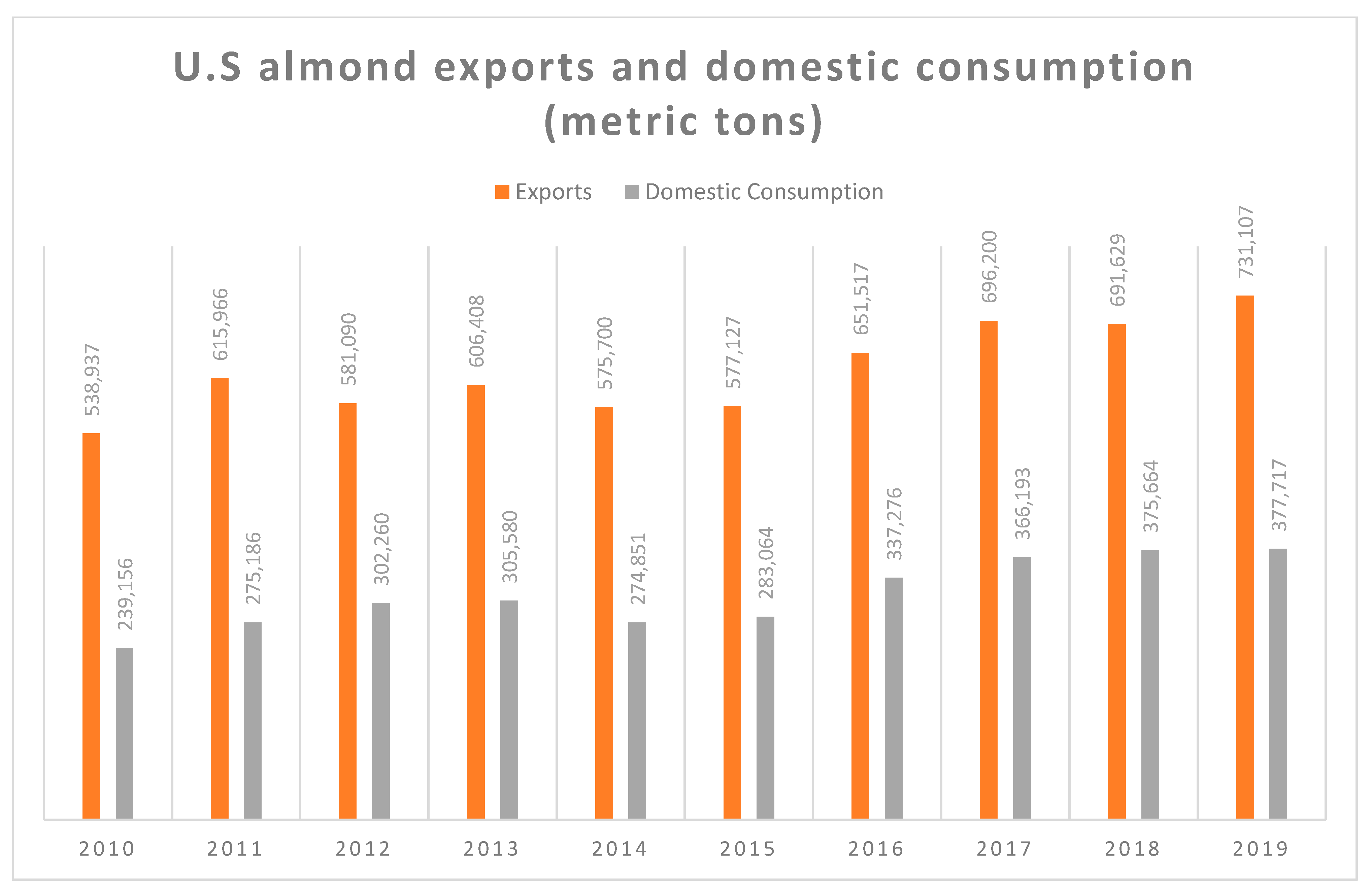

When it comes to consumption and exports, the U.S. has maintained a one-third to two-thirds ratio, where one-third of produced almonds are consumed locally, while two-thirds are exported to other countries (Figure 2). In 2019, the U.S. consumed 377,717 metric tons of almonds, or 33% of its total almonds production locally, and exported 731,177 metric tons, or 67% of the total to other countries. Local consumption grew in the last decade, just as exports did. To put this into context, the growth of almond consumption increased from 0.42 pounds per person in 1980 to 2.36 pounds in 2019 [2].

Figure 2. U.S. almond domestic consumption and exports. Source: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.

Almonds, the leading U.S. tree nut export, both in value and volume, are shipped to over 90 countries annually, with about 70% of exports going to the top 10 export destinations: China/Hong Kong, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, South Korea, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E) [2]. In 2019, U.S. tree nut exports were made up of 54% almonds valued at USD 4.9 billion, 22% pistachios valued at USD 2.0 billion, 14% walnuts valued at USD 1.3 billion, 5% pecans valued at USD 475 million, 4% ‘mixed and other nuts’ valued at USD 350 million, and 1% hazelnuts valued at USD 90 million [1].

In March 2018, the Trump administration raised tariffs on imports from key U.S. trading partners. In response, retaliatory tariffs were imposed on U.S. agricultural products. For the tree nuts industry, retaliatory tariffs were imposed on the ‘0802-tariff’ line (both in-shell and shelled nuts), causing higher tariffs on almond exports. Tariffs on almonds were raised from 10% to 55% [3][4]. The U.S. almond industry experts suggested that these tariffs would cause harm to the U.S. almond industry and the tree nuts industry in its entirety, which would, in the long run, have a negative impact on the tree-nuts-dependent economy of California. California’s economy is highly export-dependent, where 70% of almonds produced are exported to other countries [5].

2. Background

2.1. Changing Trends in World Almond Exports

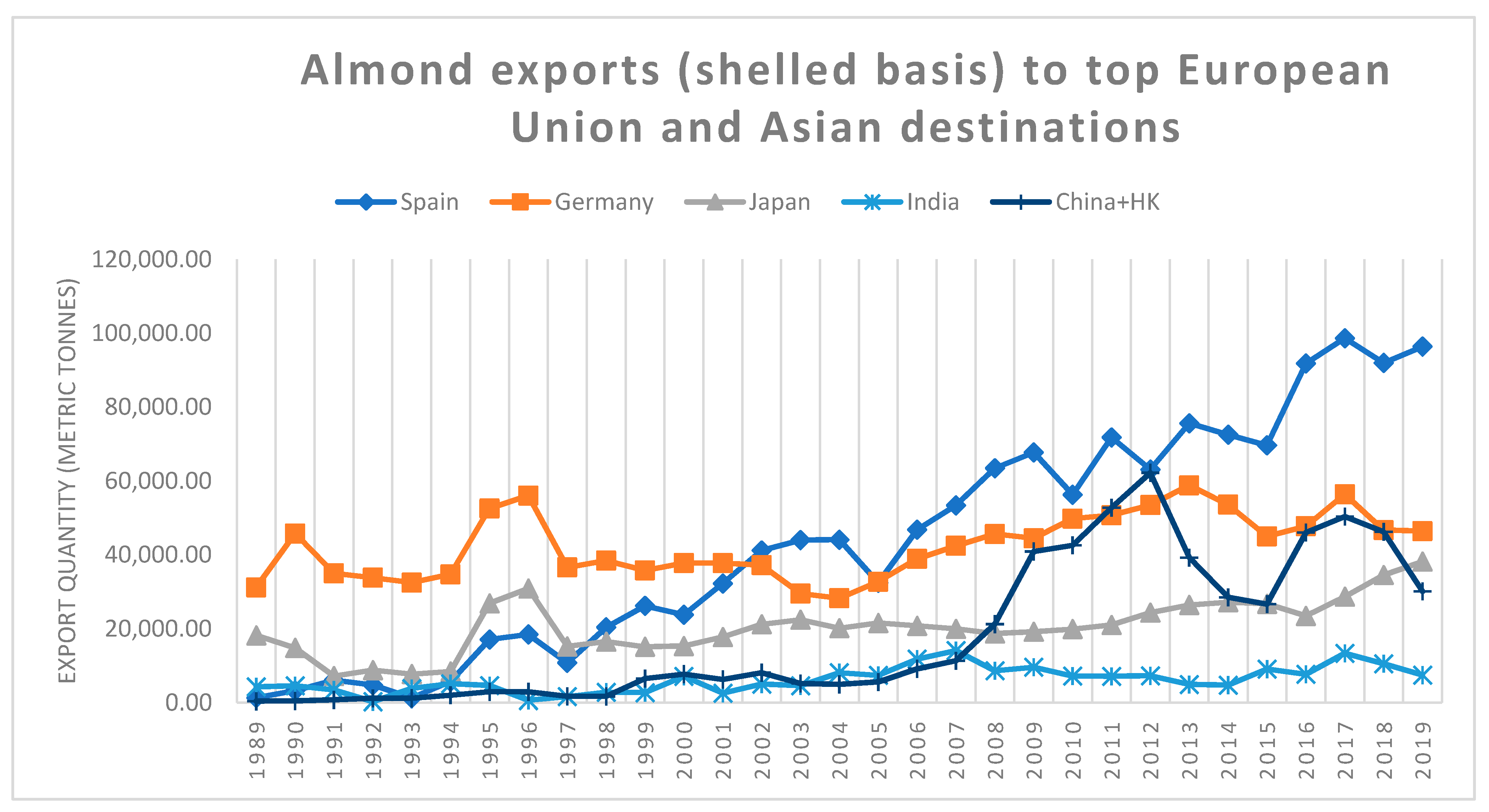

A significant part of U.S. agricultural exports to the world are tree nuts. In 2019, the U.S. exported about USD 9.1 billion worth of tree nuts, just behind soybean exports at USD 18.7 billion. The U.S. tree nut exports include almonds, pistachios, walnuts, pecans, and hazelnuts. The U.S. is the leading exporter of almonds in the world. The trends of U.S. almond exports have changed over the last 20 years (Figure 3). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, most U.S. almond exports went to the European Union (E.U) and Asia, with Germany being the major importer of U.S. almonds in the E.U., while Japan was the major importer in Asia alongside China/Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan. Emerging markets, such as India and the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E), were relatively untapped at that time [6][7].

Figure 3. U.S. almond export trends to the top European Union and Asian countries. Source: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.

Today, the E.U. remains the largest market for U.S. almond exports, importing almost 40%, and Spain now accounts for most U.S. almond imports, with Germany close behind as the second-largest E.U. importer. The Asian market, however, has seen a much more drastic change, as new export destinations, such as India, China/Hong Kong, and the U.A.E, are beginning to catch up with Japan for the share of U.S. almond exports to Asia [2]. These changing trends are the results of several years of nutrition research and global market development programs to increase U.S. almond exports. These programs are funded by both the public (the federal government) and private partners in the U.S. almond industry. The Almond Board of California (A.B.C) spent about 61% of its global budget on global market development programs in the fiscal year 2019 to boost exports to those markets [2].

2.2. Recent Trade Wars and Retaliatory Tariffs on U.S. Agricultural Exports

The dominance of U.S. tree nut exports has faced several challenges over the years, with food safety and aflatoxin concerns being among these challenges [8]. In recent years, another concern has been the retaliatory tariffs imposed on U.S. agricultural exports. After spending just over a year in office, the Trump administration announced two major tariffs against products from key trading partners: Sections 232 and 301 tariffs. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows the President to adjust imports if the Department of Commerce finds certain products are imported in certain quantities or under certain circumstances that threaten U.S. national security, while Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 allows the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to suspend trade agreement concessions or impose new import restrictions if it finds a U.S. trading partner violates trade agreement commitments or engages in discriminatory or unreasonable practices that burden or restrict U.S. commerce.

U.S. Section 232 tariffs were imposed on steel and aluminum imports from the European Union, as well as countries, such as China, Canada, Mexico, and Turkey. U.S. Section 301 tariffs were levied on imports from China [3][4]. These tariffs caused retaliatory tariffs imposed on major U.S. agricultural exports, such as meats, grains, dairy, and horticultural crops. Two of the export destinations considered in this research, namely, China and India, both imposed retaliatory tariffs on U.S. tree nut exports starting in 2018 and 2019, respectively. In April 2018, U.S. tree nuts, including almonds, pistachios, walnuts, and pecans, were slapped with retaliatory tariffs, and China and India imposed retaliatory tariffs on almonds and walnuts a year later in June 2019 [7][9].

Given the importance and contributions of almond production and exports to the California economy, the harm caused to the almond industry was transferred as an adverse effect on the Californian economy [9][10]. According to experts in this area, the tree nuts industry is export-oriented. Thus, it is adversely affected in the long run as shifting markets is expensive and time-consuming, and export promotion rewards are not gained quickly in new markets.

2.3. The Important Role of California in the U.S. Almond Crop Production

California is the only commercial producer of almonds in the U.S. and the leading supplier and exporter of almonds worldwide. California produces 100% of U.S. commercial almonds and U.S. imports remain negligible. The earliest varieties of almonds were native to western Asia and were introduced to California by Spanish explorers in the 1700s. The Spanish are generally referred to as ‘the originators’ because Franciscan padres from Spain originally introduced the almond trees to California [11]. Today, almonds are California’s top agricultural export and largest tree nut crop in total dollar value and acreage. Almonds also rank as the largest U.S. specialty crop export, generating about USD 4.9 billion in 2019 [11]. Almond production in California is carried out within a well-defined community of farmers. There are about 7600 almond farms in California. Most of these farms (91%) are family-owned and run by third- and fourth-generation farmers carrying on the family legacy in almond production. Approximately one-third of California almond farms are 100 acres or more in size.

The almond industry community includes almond handlers who move almonds from farm gates to trade points as local or export shipments. The handlers may also carry out processes such as cleaning, sizing, sorting, and bulk packaging. The handling end of the supply chain is like the production end, as most handlers of almonds are also family-owned entities [2][12].

The single most important factor determining a good almond yield is pollination during the bloom period. California almond varieties are self-incompatible, i.e., they require cross-pollination with other varieties to produce the crop. In cases where the varieties are self-compatible, they still require the transfer of pollen within the flower [13]. During the almond-growing season between February and March, almond tree buds bloom in preparation for pollination by managed (mostly imported) honeybee colonies. As blooming occurs, honeybees in search of pollen and nectar go into the almond orchards and as they move around the orchards, they pollinate the blooming flowers, allowing for the fertilization process to occur, and eventually, fertilized flowers grow into almond nuts [11].

2.4. Almond Industry Sustainability Crisis

The almond crop has high water demands for growth and ranks highest among all tree nuts in terms of its water footprint on the environment. Almonds rank higher in water use compared with both pistachios and walnuts. Thus, there are questions surrounding the sustainability of water resources and the economic cost of water in the long run if almonds are to be produced in an environmentally sound and cost-friendly manner [14].

From an economic standpoint, having over 80% of the world’s almond exports coming from California could be unsustainable in the long run. Finding other locations across the world where almonds could also be grown (such as Spain and Australia) could help to sustain the world supply of almonds [15]. High costs and supply uncertainty of water due to lengthy California droughts could cause long-run economic problems for almond producers, as they would have to pay more money for water due to water scarcity and the high demand for water by the Californian agricultural industry [16][17].

In 2018, the California almond industry used up approximately 70% of honeybee colonies in the U.S. during its pollination season (between February and March). Each almond kernel must be individually pollinated for fruit setting to occur since almond trees are self-incompatible, requiring cross-pollination to produce nuts [18][19][20]. Commercial bee pollinators flock to California due to the high pollination prices offered by the almond producers. Earning income from almond pollination services is very important to commercial bee pollinators [20]. However, the long-term sustainability of the commercial pollination industry has also been put into question, as the mass transshipment of bee colonies has led to declines in managed pollinator populations (colony collapse disorder). Cross-country transport of migratory, managed honeybee colonies can be stressful to honeybees, as the trip to pollinate California almonds for over a month (4 to 6 weeks) demonstrates [21].

3. Previous Literature

Specification of export demand functions is a widely studied research area in international trade literature and remains an important source of information for industry experts. Much of the previous literature focused on how the importing countries’ income and exchange rates affect the export demand function. Aggregate export demand forecasts and estimates serve as a tool for long-term international trade planning and policy formulation [22]. Many empirical studies used the export demand function in the past. Research was conducted on U.S. export demand for different commodities in the agricultural sector (e.g., [7][8][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40]).

Previous research estimated the major factors affecting U.S. almond export demand in Asia and the European Union (E.U.), with a focus on the impact of federal promotion programs on the export demand [7]. Results showed that own-price elasticities for almond exports were negative, and the cross-price elasticities with respect to walnuts were positive, indicating walnuts to be substitutes for almonds. Interestingly, they found mixed results for the income elasticity, with a negative income elasticity for Asia, suggesting almonds here are an inferior good. That is, with an increase in income, almond consumption decreased. However, income elasticity for the E.U. was positive and highly elastic, suggesting almonds to be a luxury good.

Past research [25] showed the relation between U.S. export demand and exchange rates. This research focused on estimating the export demand function for U.S. wheat. These results suggested exchange rate changes had a significant impact on U.S. wheat exports. Another study [26] demonstrated the determinants of trade flows in international markets. The reasons for the decline in export demand in agriculture markets back in 1986 were old and wrong policy implications, lower-than-normal levels of stocks, and government intervention in agricultural trade, which caused confusion in the markets, leading to an increase in demand and a decrease in supply, which, in return, increased prices in the markets [27].

Previous studies analyzed export demand for specific countries and the factors impacting such export demand. These include studies on export demand for U.S. cotton [28], orange juice [29], corn and soybean [30], and beef [31]. In an analysis of export demand elasticities for 53 developed and developing countries, the trading country’s income and relative commodity prices were found to be statistically significant in impacting export demand [32]. Turkish aggregated export demand was found to be inelastic (not responsive) with respect to the real exchange rate, but elastic (responsive) with respect to foreign income [33].

Past research has also demonstrated the benefits of marketing orders and the impacts of the conditions and costs of global trade, including tariffs. The benefits of the federal marketing order over the past 50 years for California pistachios were found to greatly exceed costs [34]. U.S. peanut exports were found to be influenced by both the price of Chinese peanut exports, as well as the real gross domestic product (GDP) of China [35]. The export demand function was modeled in Indonesia [36] and for U.S. corn seed export to 48 countries [37], which concluded that trade costs matter, mostly as tariffs, and that all such costs of global trade have a negative impact on exports.

The export demands for pistachios in 21 major export destinations were analyzed using a single framework logarithmic model [8]. The results showed that variation in export demand for U.S. pistachios in these markets was significantly affected by export prices of U.S. pistachios, export prices of other U.S. tree nuts (pecans, almonds, and walnuts), and food safety concerns for pistachios produced in the U.S. and its main competitor, namely, Iran. It was argued that the U.S. producers could expand the export demand for U.S. pistachios by taking advantage of the advanced production technologies they employ to improve food safety and quality and differentiate their products in international markets.

The export demand function for U.S. raisins was also investigated [38]. Other studies regarding the raisin situation were more focused on consumer marketing issues [39] and consumer demand [40].

Overall, these studies estimated the determinants of export demand and usually showed factors such as product own-price, cross-prices (product substitute/complement prices), exchange rates, and importing countries’ GDP to be significant factors affecting the export demand function.

References

- United States Department of Agriculture; Foreign Agricultural Service. United States Agricultural Export Yearbook; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Almond Board of California. Almond Almanac; Almond Board of California: Modesto, CA, USA, 2020.

- Regmi, A. China’s Retaliatory Tariffs on U.S. Agriculture: In Brief; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Williams, B.R. Trump Administration Tariff Actions: Frequently Asked Questions; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Konduru, S.; Asci, S. A Study of the Chinese Retaliatory Tariffs on Tree Nuts Industry of California. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2019, 9, 2747–2755.

- Johnson, D.C. United States is World Leader in Tree Nut Production and Trade. In USDA-ERS Fruit and Tree Nuts Situation and Outlook. FTS-280; U.S. Department of Agriculture—Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- Onunkwo, I.M.; Epperson, J.E. Export Demand for U.S. Almonds: Impacts of U.S. Export Promotion Programs. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2001, 32, 140–151.

- Zheng, Z.; Saghaian, S.H.; Reed, M.R. Factors Affecting the Export Demand for U.S. Pistachios. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 139–154.

- Sumner, D.A.; Matthews, W.A.; Medellín-Azuara, J.; Bradley, A. The Economic Impacts of the California Almond Industry; University of California Agricultural Issues Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014.

- Carter, C.A.; Steinbach, S. Impact of the U.S-China Trade War on California Agriculture. ARE Update 2019, 23, 9–11.

- Almond Board of California. Almond Almanac; Almond Board of California: Modesto, CA, USA, 2019.

- Sumner, D.A.; Hanon, T.; Matthews, W.A. Implication of Trade Policy Turmoil for Perennial Crops. Choices 2019, 34, 1–9.

- Almond Board of California. California Almond Industry Facts; Almond Board of California: Modesto, CA, USA, 2016.

- Fulton, J.; Norton, M.; Shilling, F. Water-indexed Benefits and Impacts of California almonds. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 711–717.

- Marston, L.; Konar, M. Drought Impacts to Water Footprints and Virtual Water Transfers of the Central Valley of California. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 5756–5773.

- Howitt, R.; Medellín-Azuara, J.; MacEwan, D.; Lund, J.R.; Sumner, D. Economic Analysis of the 2014 Drought for California Agriculture; Center for Watershed Sciences, University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2014.

- Sumner, D.A.; Hanak, E.; Mount, J.; Medellín-Azuara, J.; Lund, J.R.; Howitt, R.E.; MacEwan, D. The Economics of the Drought for California Food and Agriculture. Agric. Resour. Econ. Update 2015, 18, 1–6.

- Sumner, D.A.; Boriss, H. Bee-conomics and the Leap in Pollination Fees. Agric. Resour. Econ. Update 2006, 9, 9–11.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Honeybee Colonies; USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Lee, H.; Sumner, D.A.; Champetier, A. Pollination Markets and the Coupled Futures of Almonds and Honeybees: Simulating Impacts of Shifts in Demands and Costs. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 101, 230–249.

- Aebi, A.; Neumann, P. Endosymbionts and Honeybee Colony Losses? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 494.

- Arize, A.C. Traditional Export Demand Relation and Parameter Instability: An Empirical Investigation. J. Econ. Stud. 2001, 28, 378–396.

- Guci, L. Exchange Rates and The Export Demand for US Grapefruit Juice; Research Papers 36816; Florida Department of Citrus: Bartow, CA, USA, 2008.

- Hooy, C.W.; Choong, C.K. Export Demand within SAARC Members: Does Exchange Rate Volatility Matter. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2010, 4, 373–390.

- Konandreas, P.; Bushnell, P.; Green, R. Estimation of Export Demand Functions for U.S. Wheat. J. West. Econ. 1978, 3, 39–49.

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M. Determination of International Trade Flows. J. Dev. Econ. 1986, 20, 107–123.

- Haniotis, T.; Baffes, J.; Ames, G.W. The Demand and Supply of U.S. Agricultural Exports: The Case of Wheat, Corn and Soybean. South. J. Agric. Econ. 1988, 20, 45–56.

- Duffy, P.A.; Wohlgenant, M.K.; Richardson, J.W. The Elasticity of Export Demand for U.S. Cotton. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1990, 72, 468–474.

- Armah, B.K., Jr.; Epperson, J.E. Export Demand for U.S. Orange Juice: Impacts of U.S. Export Promotion Programs. Agribusiness 1997, 13, 1–10.

- Saghaian, Y.; Reed, M.; Saghaian, S. Export Demand Estimation for U.S. Corn and Soybeans to Major Destinations. In Proceedings of the 2014 Southern Agricultural Economics Association (SAEA) Annual Meeting in Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA, 1–4 February 2014.

- Eenoo, E.V.; Peterson, E.; Purcell, W. Impact of Exports on the U.S. Beef Industry; Staff Papers 232380; Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VI, USA, 2000.

- Senhadji, A.S.; Montenegro, C.E. Time Series Analysis of Export Demand Equations: A Cross-Country Analysis. IMF Staff. Pap. 1999, 46, 259–273.

- Cosar, E.E. Price and Income Elasticities of Turkish Export Demand: A Panel Data Application. Cent. Bank Rev. 2002, 2, 19–53.

- Gray, R.S.; Sumner, D.A.; Alston, J.M.; Brunke, H.; Acquaye, A.K. Economic Consequences of Mandated Grading and Food Safety Assurance: Ex ante Analysis of the Federal Marketing Order for California Pistachios; University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2005.

- Boonsaeng, T.; Fletcher, S.M. The Impact of U.S. Non-price Export Promotion Program on Export Demand for U.S. Peanuts in North America. J. Peanut Sci. 2010, 37, 70–77.

- Hussein, A. Structural Change in the Export Demand Function for Indonesia: Estimation, Analysis and Policy Implications. J. Policy Mark. 2009, 31, 260–271.

- Jayasinghe, S.; Beghin, J.C.; Moschini, G. Determinants of World Demand for U.S. Corn Seeds: The Role of Trade Costs. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 92, 999–1010.

- Soltani, M.; Saghaian, S. Export Demand Function Estimation for U.S. Raisins. Presented at the 2012 Southern Agricultural Economics Association (SAEA) Annual Meeting in Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA, 4–7 February 2012.

- Keeling, J.J.; Andersen, M.A. Welfare Analysis and Policy Recommendations for the California Raisin Marketing Order. Presented at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting in Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 1–4 August 2004.

- Brant, M.; Marsh, T.L.; Featherstone, A.M.; Crespi, J.M. Multivariate AIM Consumer Demand Model Applied to Dried Fruit, Raisins, and Dried Plums (No. 378-2016-21219). In Proceedings of the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Providence, RI, USA, 24–27 July 2005.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agricultural Economics & Policy

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

4.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No