Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ali Mirzaei | -- | 3954 | 2022-06-25 09:58:14 | | | |

| 2 | Ali Mirzaei | + 194 word(s) | 4148 | 2022-06-25 10:03:02 | | | | |

| 3 | Dean Liu | -1483 word(s) | 2665 | 2022-06-27 09:02:18 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mirzaei, A.; Kim, J.; Kordrostami, Z.; Shahbaz, M.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, H.W. Resistive-Based Gas Sensors Using Pristine Quantum Dots. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24474 (accessed on 25 January 2026).

Mirzaei A, Kim J, Kordrostami Z, Shahbaz M, Kim SS, Kim HW. Resistive-Based Gas Sensors Using Pristine Quantum Dots. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24474. Accessed January 25, 2026.

Mirzaei, Ali, Jin-Young Kim, Zoheir Kordrostami, Mehrdad Shahbaz, Sang Sub Kim, Hyoun Woo Kim. "Resistive-Based Gas Sensors Using Pristine Quantum Dots" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24474 (accessed January 25, 2026).

Mirzaei, A., Kim, J., Kordrostami, Z., Shahbaz, M., Kim, S.S., & Kim, H.W. (2022, June 25). Resistive-Based Gas Sensors Using Pristine Quantum Dots. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24474

Mirzaei, Ali, et al. "Resistive-Based Gas Sensors Using Pristine Quantum Dots." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Quantum dots (QDs) are used progressively in gas sensing applications because of their special electrical properties resulting from their extremely small size. QDs show a high sensing performance at generally low temperatures owing to their extremely small sizes, making them promising materials for the realization of reliable and high-output gas-sensing devices. This article discusses the gas sensing features of QD-based resistive sensors. Different types of pristine QD gas sensors for the detection of various gases are discussed in this article.

Quantum dots (QDs)

gas sensor

toxic gas

sensing mechanism

1. Resistive-Based Gas Sensors: Basics

Air pollution is a global problem that caused ~4.9 million premature deaths in 2017 [1]. The human olfactory system is highly sensitive and can discriminate different odors. On the other hand, some dangerous gases are odorless. In some cases, the extremely low concentration of gases is not detectable by the human olfactory system. Furthermore, in many places, humans are not present or cannot be present to detect the odor of gases. Thus, sensitive devices of small size and high performance are needed to detect various toxic gases and vapors reliably [2]. Some techniques, such as ion chromatography and gas chromatography, require multi-step laboratory procedures. In addition, they are expensive, bulky, and cannot offer online signals [3][4].

There are various types of gas sensors, including surface acoustic waves [5], mass-sensitive [6], infrared [7], and optical [8], based on different materials and principles [9]. They are used for public security, environmental control, chemical quality control, safety in homes, automotive applications, air conditioning, and breath analysis for medical diagnoses [10][11]. Among the different gas sensors, conductometric sensing devices are popular owing to unique features, including (i) low cost, (ii) ease of fabrication and use, (iii) high response, (iv) high stability, (v) easy integration into sensor arrays, and (vi) simple operation [12]. Bradeen and Bradeen were the first to discover the gas-sensitive influences on semiconducting germanium [13]. Seiyama et al. [14] reported the first metal oxide gas sensor based on ZnO for toluene, CO2, and propane sensing. Taguchi later patented a SnO2 gas sensor and soon commercialized it [15].

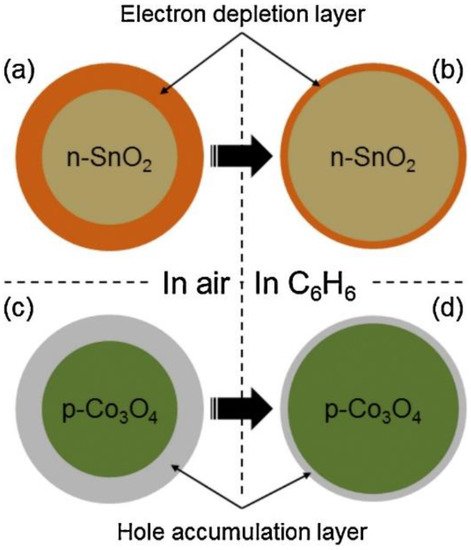

The principle of the sensing mechanism is modulation of the sensor resistance in different atmospheres [16]. Depending on the n-type or p-type nature of the sensing layer and the nature of the gas, the electrical resistance of sensing device changes in proportion to the amount of gas. In n-type materials, such as SnO2, an electron depletion layer initially exists in the air by adsorbed oxygen ions and subsequent exposure to a reducing gas. The liberated electrons return to the surface of the sensing layer, narrowing the width of the electron depletion layer. Therefore, they contribute to the sensor signal. For p-type materials, a hole accumulation layer exists initially in the air. The width of this layer decreases in a reducing gas medium, leading to an increase in sensor resistance. Figure 1 shows the mechanisms for n- and p-type gas sensors when a reducing gas is present [17].

Figure 1. Sensing mechanism of n-SnO2 and p-Co3O4 (a,b) in air; (c,d) in C6H6, as an example of a reducing gas [17].

Therefore, by tracking the resistance variations, a calibration curve can be drawn and used for applications [18]. Some shortages of resistive-based gas sensors are low selectivity and high sensing temperature [19]. The performance of these types of gas sensors can be improved using a range of methods, such as the formation of p-n heterojunctions [20], noble metal decoration [21], doping [22], UV irradiation [23], morphology engineering [24][25], and decrease of particle size.

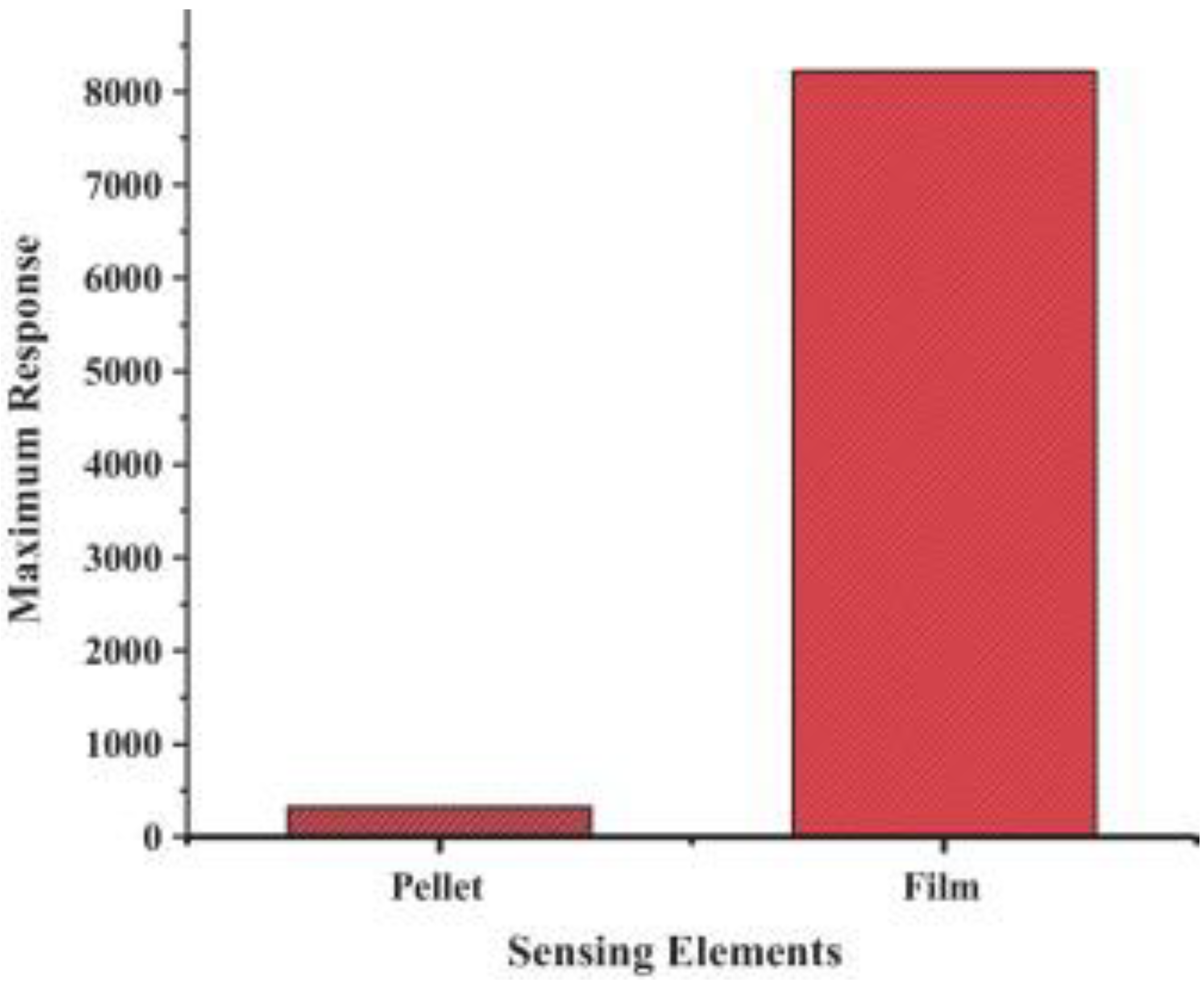

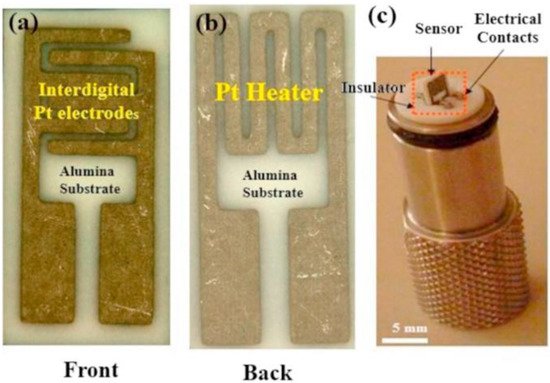

Generally, resistive-based gas sensors are fabricated by depositing a thin or thick film over an interdigitated insulator substrate [26]. The pellet form is not efficient as much of the bulk volume is inaccessible to the target gas, resulting in a lower response relative to either thin or thick film counterparts, as shown in Figure 2 [27]. Electrodes are used to provide an electrical signal for the electrical device. Sometimes a heater is incorporated in the backside of the substrate to offer the necessary temperature for operation [28]. Figure 3 presents the front and back sides of an alumina substrate equipped with electrodes and heaters in the front and back sides, respectively [29].

Figure 2. Response of NdFeO3 pellet and film gas sensors to LPG [27].

Figure 3. (a) Front; (b) back sides of an alumina substrate for gas sensing studies; (c) Sensor holder [29].

2. Resistive-Based Gas Sensors Based on QDs

2.1. Pristine Metal Oxide and Metal Sulfide QD Gas Sensors

2.1.1. SnO2-Based Gas Sensors

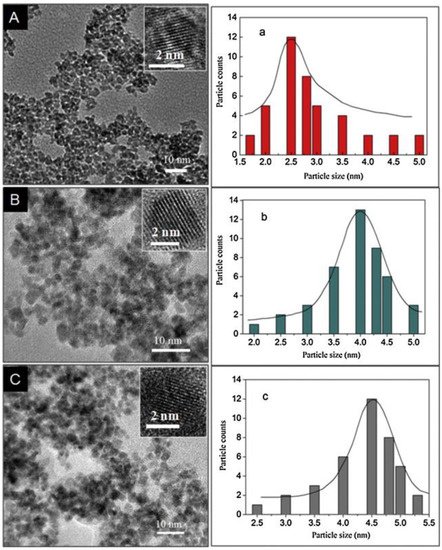

SnO2 is a widely used material for sensing studies [30] because of its low price, good stability, and high mobility of electrons [30]. In this direction, Xu et al. [31] investigated the grain size effects in SnO2 gas sensors and reported that the gas-sensing features of SnO2 were enhanced by reducing the grain sizes. In particular, the sensing properties were increased when the grain size was comparable to the Debye length. Liu et al. [32], prepared SnO2 QDs (2.0–12.6 nm) and reported that the sensing response was significantly increased when the grain size was close to the Debye length of SnO2. Generally, the quantum size effects appear when the size of the SnO2 nanoparticles (NPs) is about 1–10 nm [33]. Du et al. [34] prepared SnO2 QDs via a hydrothermal route. By varying the amounts of alkaline reagent, the size of SnO2 QDs was adjusted to 2.5 ± 0.3 nm, 4.0 ± 0.3 nm, and 4.5 ± 0.3 nm (Figure 4).

Figure 4. (A–C) TEM and HRTEM (insets) micrographs, and (a–c) relevant size distributions of SnO2 QDs prepared by hydrothermal synthesis [34].

A previous study reported that at 240 °C, the response of SnO2 QDs to trimethylamine (TEA) increased with a decreasing SnO2 QDs size. First, because the size range of gas sensors was close to the Debye length of SnO2 and smaller than twice the thickness of the electron depletion layer (EDL), the entire crystal became depleted from electrons. Hence, subsequent exposure to TEA and the huge amount of resistance modulation causes a strong response on the gas sensors. Second, with further increases in size, the quantum confinement effect becomes more evident, and the surface defects increase. Thus, the highest responses to TEA were observed in a sensor with the smallest grain sizes.

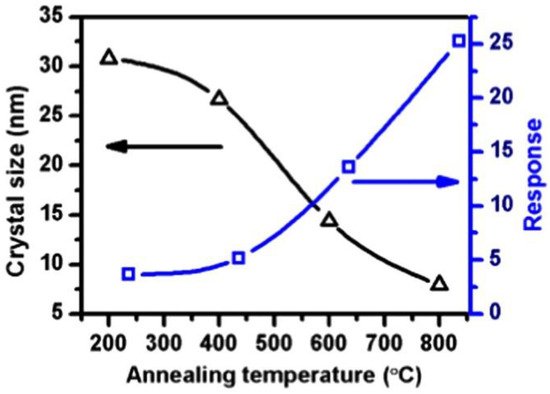

Generally, high temperatures, complex organic solutions, and long reaction times are needed to prepare SnO2 QDs with ultra-small sizes. On the other hand, He et al. [35] reported a facile, room temperature precipitation method to synthesize ~2.5 nm SnO2 QDs. SnO2 QDs with different sizes were synthesized without needing a capping agent or an organic solvent or annealing at different temperatures. As shown in Figure 5, SnO2 QDs showed an enhanced response to ethanol gas relative to SnO2 NPs. The SnO2 QDs with a small size of 3.7 nm revealed a strong response to 30–50 ppm ethanol at 200 °C with fast response (1 s) and recovery (1 s) times. The strong response was related to the complete depletion of SnO2 QDs from electrons in air and subsequent resistance variation in the presence of ethanol.

Figure 5. Sensing response and crystalline size of the SnO2 samples as a function of the annealing temperature [35].

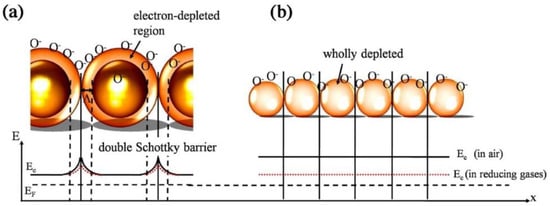

Zhu et al. [36] synthesized SnO2 QDs (5–10 nm) by a microwave (MW)-assisted wet chemical method at 160 °C and subsequent annealing at 400 °C. In polycrystalline SnO2 grains, double Schottky barriers form between two neighboring grains in air and the motion of electrons is restricted in air (Figure 6a). Thus, the resistance is high in the air. In reducing gas atmosphere, the height of barriers decreases, increasing the conductance. When the particle size is smaller than the EDL thickness, the electron-depleted regions overlap (Figure 6b). In the case of SnO2 QDs, the whole SnO2 crystals become electron-depleted in air, and a ‘flat-band’ condition was expected. The energy difference between the conduction band (Ec) and Femi level (EF) is increased. In a reducing gas atmosphere, the electrons return to the SnO2 QD surface, and the whole grains become more conducting than in the air, and an enhancement of gas sensitivity is expected.

Figure 6. Sensing mechanism of SnO2 QDs. (a) formation of double Schottky barriers; (b) energy levels in SnO2 QDs when the grains are smaller than the thickness of the space charge layer [36].

Colloidal QDs (CQDs) are semiconductor nanocrystals dispersed in solution. Solution processability can be obtained using long-chain ligands, such as oleic acid (OA) or oleylamine (OLA) capping on the CQD surfaces [37]. Liu et al. [38] synthesized OA and OLA capped SnO2 CQDs for H2S sensing studies. As reported elsewhere [39], these capping agents have long carbon chains that generate insulating barriers between CQDs and hinder efficient gas adsorption and carrier transport, resulting in poor gas sensing performance. Therefore, after spin coating the substrate, a surface ligand treatment was applied using AgNO3, NaNO3, NaNO2, KNO2, and NH4Cl to exchange long-chain surface-capping ligands. The ligand-treated samples showed a sensitive response to H2S gas. In particular, AgNO3-treated SnO2 CQD film revealed the strongest response to this gas. Characterization techniques approved the presence of Ag2O, which is a promising material for H2S gas sensing. At 70 °C, the AgNO3-treated SnO2 CQDs gas sensor indicated a high response to 29–50 ppm of H2S gas. In SnO2 CQD sensors, all the SnO2 CQDs become completely depleted from electrons because of their small sizes (~up to 10 nm). Hence, there are no surface barriers because there are no electrons in the entire crystal. Upon exposure to H2S gas, the Fermi level (EFg) becomes much closer to the conduction band, resulting in a more conductive state. Therefore, the sensor response is related to the Fermi level shift, which depends on the amount of gas.

2.1.2. ZnO QDs Gas Sensors

Semiconducting n-ZnO (Eg = 3.37 eV), which has high electron mobility and highly stable chemical and thermal properties, is popular for sensing studies [22][40]. Zhang et al. [41] prepared OA- capped ZnO CQDs using a facile colloidal method. OA capping was performed to avoid agglomeration. The OA-capped sensor revealed almost no response to H2S gas. The OA with long chains carbon limits electron flow and prevents gas molecules react with the ZnO surface. However, after treatment of the capping agent with different agents, the ZnCl2-treated gas sensor exhibited a response of 113.5 to 50 ppm of H2S gas. Nevertheless, its recovery was still poor. Upon annealing at 300 °C, the sensor showed a response of 113.5 with relatively fast recovery time. Forleo et al. [42] prepared ZnO QDs (2.5–4.5 nm) using a wet chemical method for gas sensing studies. At low temperatures, the sensor exhibited a high response to NO2 gas, whereas at T > 350 °C, strong responses to acetone and methanol were recorded. However, the recovery time was very long.

2.1.3. TiO2 QDs Gas Sensors

N-type semiconducting TiO2 is non-toxic, inexpensive, highly stable, and has unique electro–optical properties [43][44]. Liu et al. [46] prepared TiO2 QDs with a high surface area (315.74 m2/g). At 25 °C, it showed a good response of 7.8 to 10 ppm NH3 gas. The sensing mechanism was described based on the generation of EDL on TiO2 QDs.

2.1.4. PbS QD Gas Sensors

Lead sulfide (PbS) is used widely for sensing studies [45][46][47]. Liu et al. [48] prepared PbS CQD sensors for NO2 gas-sensing applications. They compared the sensing output of the gas sensor on three substrates: Al2O3, PET, and paper at room temperature. The paper-based gas sensor revealed a high response of 21.7 to 50 ppm of NO2, whereas the responses for sensors on Al2O3 and PET substrates, respectively, were 13.0 and 3.5. The strong response on the paper substrate was due to the rough and porous nature of paper, which led to high porosity and better exposure of the CQD surfaces to the target gas molecules. They also explored the fatigue and bending characteristics of the paper-based gas sensor. Even after 180° bending, the resistance showed almost no changes. Furthermore, the sensor prepared with a Pb to S ratio of 4:1 during synthesis showed a stronger response to NO2 gas because of more Pb cations residing on the surface, where the adsorption of NO2 molecules was improved, which was beneficial for sensing of NO2 gas. In another study, the effect of the PbS QDs film thickness on the NO2 gas response was reported [49]. The size of the QDs was ~4 nm and different QD films with thicknesses in the range from 500 nm to 1500 nm were deposited on the sensor substrate. The sensor with a thickness of ~1000 nm showed the best response to NO2 gas. NO2 has a high oxidation potential, acting as a p-type dopant for PbS, increasing the number of free holes. The highest response was recorded for a sensor with a thickness of ~1000 nm; however, the reasons were not mentioned.

2.1.5. ZnS QD Gas Sensor

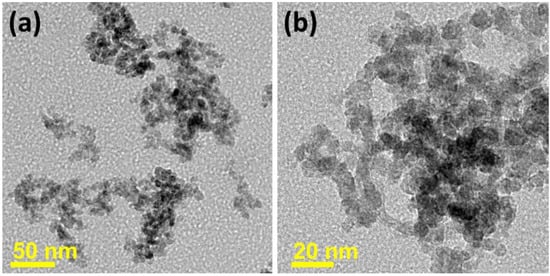

Mishra et al. [50] synthesized ZnS QDs (Figure 7) for acetone-sensing application. At 174 °C, the sensor indicated selectivity to acetone gas. The strong response to acetone was owing to the high surface area of QDs, which provided large chemisorption of acetone molecules. Furthermore, the rapid response (5.5 s) and recovery time (6.7 s) of ZnS QDs were related to the fast adsorption of oxygen species and their quick interactions with acetone molecules due to the quantum size effects of ZnS QDs.

Figure 7. TEM images of (a) overlapped ZnS QDs; (b) different sizes of ZnS QDs [50].

2.1.6. SnS QD Gas Sensors

SnS has low toxicity and low cost, with a direct and indirect bandgap of 1.0 eV and 1.3 eV, respectively. In this compound, Van der Waal’s force is responsible for bonding Sn and S atoms [51]. The charge exchange between polar gases and SnS is favored because of the anisotropic crystal structure of SnS, making it a good candidate for sensing applications [54,[52]. Rana et al. [53] synthesized SnS QDs for ethanol sensing. At 300 °C, it showed a good response and high selectivity to ethanol gas. The ultrafine size, chain-like structure, and appropriate stoichiometry of the SnS QDs improved the response to ethanol gas.

Wang et al. [54] prepared SnS CQDs for low temperature NO2 gas sensing. The sensor exhibited a p-type response and good selectivity to NO2 gas. Owing to the paramagnetic nature of NO2, upon adsorption, it produces a magnetic dipole beside a surface electric dipole that was generated by the charge. Thus, surface dipoles were formed on the gas sensor, leading to good electron transfer from SnS to NO2. Accordingly, a strong response to NO2 gas was observed.

2.1.7. PbCdSe QD Gas Sensor

A new bimetallic PbxCd1−xSe QD (QD) gel consisted of dispersed Pb ionic sites into CdSe crystal revealed a strong response and fast dynamics to NO2 gas at 25 °C. The DFT calculation results indicated that Cd sites were responsible for the high NO2-sensing output because they offer remarkably higher charge transfer but comparable adsorption energy relative to the Pb sites. The Pb ionic sites acted as the transfer electron density to the neighboring Cd cations, causing them suitable electron donors to NO2 gas, improving the gas sensor response [55].

The pristine QD-based gas sensors have merits, such as ease of synthesis and relatively simple operation and mechanism. To realize high-performance gas sensors, it is essential to combine two or three QDs to make heterojunctions and use the synergetic effects between the different materials. The following section provides details of composite QD-based gas sensors.

3. Conclusions

This paper discussed the gas-sensing features of different QD-based resistive gas sensors. The most widely used materials in the form of QDs for gas-sensing applications are metal oxides such as SnO2 and ZnO, and metal sulfides such as PbS. Due to their extremely fine size, generally, QD-based gas sensors work at low or room temperatures. In particular, the room temperature QD-based gas sensors generally show high sensitivity, high selectivity, and fast dynamics owing to the extremely small size of QDs with a high-surface-area and quantum size effects. There are some considerations related to the development of QD-based gas sensors. First, due to their very small sizes, they tend to be agglomerated, which can lead to the instability of gas sensors or decreases in sensing performance. Therefore, the development of synthesis methods or post-synthesis methods to have discrete QDs for sensing studies is necessary. Additionally, the current synthesis methods are not able to synthesize the large-scale of QDs. Furthermore, exact control of the shape of QDs is difficult. Thus, researchers need to develop more novel and flexible routes to not only control the size and shape of QDs but to also produce QDs on large scales.

References

- Zhang, L.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Tao, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Luo, Y. Application of nonlinear land use regression models for ambient air pollutants and air quality index. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 101186.

- Mirzaei, A.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, H.W. Resistance-based H2S gas sensors using metal oxide nanostructures: A review of recent advances. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 357, 314–331.

- Lau, H.C.; Yu, J.B.; Lee, H.W.; Huh, J.S.; Lim, J.O. Investigation of exhaled breath samples from patients with Alzheimer’s disease using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and an exhaled breath sensor system. Sensors 2017, 17, 1783.

- Michalski, R.; Pecyna-Utylska, P.; Kernert, J. Determination of ammonium and biogenic amines by ion chromatography. A review. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1651, 462319.

- Patial, P.; Deshwal, M.J.T.O.E.; Materials, E. Systematic review on design and development of efficient semiconductor based surface acoustic wave gas sensor. Transcation Electical Electron. Mater. 2021, 22, 1–9.

- Oprea, A.; Weimar, U.J.A.; Gas sensors based on mass-sensitive transducers. Part 1: Transducers and receptors—basic understanding. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 1761–1787.

- Popa, D.; Udrea, F.J.S. Towards integrated mid-infrared gas sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 2076.

- Hodgkinson, J.; Tatam, R.P.J.M.S. Optical gas sensing: A review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 24, 012004.

- Nazemi, H.; Joseph, A.; Park, J.; Emadi, A. Advanced micro- and nano-gas sensor technology: A review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1285.

- Kim, I.-D.; Rothschild, A.; Tuller, H.L. Advances and new directions in gas-sensing devices. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 974–1000.

- Comini, E. Metal oxide nano-crystals for gas sensing. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 568, 28–40.

- Mirzaei, A.; Neri, G. Microwave-assisted synthesis of metal oxide nanostructures for gas sensing application: A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 237, 749–775.

- Brattain, W.H.; Bardeen, J. Surface properties of germanium. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1953, 32, 1–41.

- Seiyama, T.; Kato, A.; Fujiishi, K.; Nagatani, M. A new detector for gaseous components using semiconductive thin films. Anal. Chem. 1962, 34, 1502–1503.

- Taguchi, N. A Metal Oxide Gas Sensor. Japanese Patent 4,538,200, 1962.

- Korotcenkov, G.; Cho, B.K. Metal oxide composites in conductometric gas sensors: Achievements and challenges. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 244, 182–210.

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Mirzaei, A.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Optimization and gas sensing mechanism of n-SnO2-p-Co3O4 composite nanofibers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 248, 500–511.

- Kim, J.H.; Mirzaei, A.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Combination of Pd loading and electron beam irradiation for superior hydrogen sensing of electrospun ZnO nanofibers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 284, 628–637.

- Mirzaei, A.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. How shell thickness can affect the gas sensing properties of nanostructured materials: Survey of literature. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 258, 270–294.

- Miller, D.R.; Akbar, S.A.; Morris, P.A. Nanoscale metal oxide-based heterojunctions for gas sensing: A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 204, 250–272.

- Singhal, A.V.; Charaya, H.; Lahiri, I. Noble metal decorated graphene-based gas sensors and their fabrication: A review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2017, 42, 499–526.

- Wang, C.N.; Li, Y.L.; Gong, F.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Fang, S.M.; Zhang, H.L. Advances in doped ZnO nanostructures for gas sensor. Chem. Rec. 2020, 20, 1553–1567.

- Espid, E.; Taghipour, F. UV-LED photo-activated chemical gas sensors: A review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2017, 42, 416–432.

- Bag, A.; Lee, N.-E. Gas sensing with heterostructures based on two-dimensional nanostructured materials: A review. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 13367–13383.

- Li, T.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Z. Quasi-one-dimensional metal-oxide-based heterostructural gas-sensing materials: A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 221, 1570–1585.

- Nikolic, M.V. An overview of oxide materials for gas sensors. In Proceedings of the 2020 23rd International Symposium on Design and Diagnostics of Electronic Circuits & Systems (DDECS), Novi Sad, Serbia, 22–24 April 2020; pp. 1–4.

- Singh, S.; Singh, A.; Yadav, B.C.; Dwivedi, P.K. Fabrication of nanobeads structured perovskite type neodymium iron oxide film: Its structural, optical, electrical and LPG sensing investigations. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 177, 730–739.

- Neri, G. First fifty years of chemoresistive gas sensors. Chemosensors 2015, 3, 1–20.

- Mirzaei, A.; Janghorban, K.; Hashemi, B.; Bonyani, M.; Leonardi, S.G.; Neri, G. A novel gas sensor based on Ag/Fe2O3 core-shell nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 18974–18982.

- Yamazoe, N.; Sakai, G.; Shimanoe, K. Oxide semiconductor gas sensors. Catal. Surv. Asia 2003, 7, 63–75.

- Xu, C.; Tamaki, J.; Miura, N.; Yamazoe, N. Grain size effects on gas sensitivity of porous sno2-based elements. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1991, 3, 147–155.

- Liu, J.; Lv, J.; Shi, J.; Wu, L.; Su, N.; Fu, C.; Zhang, Q. Size effects of tin oxide quantum dot gas sensors: From partial depletion to volume depletion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 16399–16409.

- Chen, D.; Huang, S.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Le, T.-T.; Cheng, E.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Z. Highlights on advances in SnO2 quantum dots: Insights into synthesis strategies, modifications and applications. Mater. Res. Lett. 2018, 6, 462–488.

- Du, J.; Zhao, R.; Xie, Y.; Li, J. Size-controlled synthesis of SnO2 quantum dots and their gas-sensing performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 346, 256–262.

- He, Y.; Tang, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Fan, F.; Li, D. Ultrafast response and recovery ethanol sensor based on SnO2 quantum dots. Mater. Lett. 2016, 165, 50–54.

- Zhu, L.; Wang, M.; Kwan Lam, T.; Zhang, C.; Du, H.; Li, B.; Yao, Y. Fast microwave-assisted synthesis of gas-sensing SnO2 quantum dots with high sensitivity. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 236, 646–653.

- Carey, G.H.; Abdelhady, A.L.; Ning, Z.; Thon, S.M.; Bakr, O.M.; Sargent, E.H. Colloidal quantum dot solar cells. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12732–12763.

- Liu, H.; Xu, S.; Li, M.; Shao, G.; Song, H.; Zhang, W.; Wei, W.; He, M.; Gao, L.; Song, H.; et al. Chemiresistive gas sensors employing solution-processed metal oxide quantum dot films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 163104.

- Xu, X.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, X. Sno2 quantum dots and quantum wires: Controllable synthesis, self-assembled 2d architectures, and gas-sensing properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12527–12535.

- Zhu, L.; Zeng, W. Room-temperature gas sensing of zno-based gas sensor: A review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 267, 242–261.

- Zhang, B.; Li, M.; Song, Z.; Kan, H.; Yu, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H. Sensitive H2S gas sensors employing colloidal zinc oxide quantum dots. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 249, 558–563.

- Forleo, A.; Francioso, L.; Capone, S.; Siciliano, P.; Lommens, P.; Hens, Z. Synthesis and gas sensing properties of zno quantum dots. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 146, 111–115.

- Li, Z.; Yao, Z.; Haidry, A.A.; Plecenik, T.; Xie, L.; Sun, L.; Fatima, Q. Resistive-type hydrogen gas sensor based on TiO2: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 21114–21132.

- Mohd Chachuli, S.A.; Hamidon, M.N.; Mamat, M.; Ertugrul, M.; Abdullah, N.H.J.S. A hydrogen gas sensor based on TiO2 nanoparticles on alumina substrate. Sensors 2018, 18, 2483.

- Liu, H.; Shen, W.; Chen, X.; Corriou, J.-P. A high-performance NH3 gas sensor based on TiO2 quantum dot clusters with ppb level detection limit at room temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 18380–18387.

- Li, M.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Z.; He, J.; Hu, L.; Xia, Z.; Tang, J.; Liu, H. Resistive gas sensors based on colloidal quantum dot (cqd) solids for hydrogen sulfide detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 217, 198–201.

- Li, M.; Kan, H.; Chen, S.; Feng, X.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Fu, C.; Quan, A.; Sun, H.; Luo, J.; et al. Colloidal quantum dot-based surface acoustic wave sensors for NO2-sensing behavior. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 287, 241–249.

- Mosahebfard, A.; Jahromi, H.D.; Sheikhi, M.H. Highly sensitive, room temperature methane gas sensor based on lead sulfide colloidal nanocrystals. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 4174–4179.

- Liu, H.; Li, M.; Voznyy, O.; Hu, L.; Fu, Q.; Zhou, D.; Xia, Z.; Sargent, E.H.; Tang, J. Physically flexible, rapid-response gas sensor based on colloidal quantum dot solids. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2718–2724.

- Mitri, F.; De Iacovo, A.; De Luca, M.; Pecora, A.; Colace, L. Lead sulphide colloidal quantum dots for room temperature NO2 gas sensors. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9.

- Mishra, R.K.; Choi, G.-J.; Choi, H.-J.; Gwag, J.-S. ZnS quantum dot based acetone sensor for monitoring health-hazardous gases in indoor/outdoor environment. Micromachines 2021, 12, 598.

- Li, H.; Li, M.; Kan, H.; Li, C.; Quan, A.; Fu, C.; Luo, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Yang, Z.; et al. Surface acoustic wave no2 sensors utilizing colloidal sns quantum dot thin films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 362, 78–83.

- Tang, H.; Gao, C.; Yang, H.; Sacco, L.; Sokolovskij, R.; Zheng, H.; Ye, H.; Vollebregt, S.; Yu, H.; Fan, X.; et al. Room temperature ppt-level no2 gas sensor based on sno x/sns nanostructures with rich oxygen vacancies. 2D Mater. 2021, 8, 045006.

- Rana, C.; Bera, S.R.; Saha, S. Growth of sns nanoparticles and its ability as ethanol gas sensor. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 2016–2029.

- Wang, J.; Lian, G.; Xu, Z.; Fu, C.; Lin, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Cui, D.; Wong, C.-P. Growth of large-size sns thin crystals driven by oriented attachment and applications to gas sensors and photodetectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 9545–9551.

- Geng, X.; Li, S.; Mawella-Vithanage, L.; Ma, T.; Kilani, M.; Wang, B.; Ma, L.; Hewa-Rahinduwage, C.C.; Shafikova, A.; Nikolla, E.; et al. Atomically dispersed pb ionic sites in pbcdse quantum dot gels enhance room-temperature no2 sensing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4895.

More

Information

Subjects:

Nanoscience & Nanotechnology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No