Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neo Endra Lelana | -- | 2845 | 2022-06-21 12:33:10 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 2845 | 2022-06-23 04:09:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Lelana, N.E.; Utami, S.; Darmawan, U.W.; Nuroniah, H.S.; , D.; , A.; Haneda, N.F.; Arinana, A.; Darwiati, W.; Anggraeni, I. Bagworms in Indonesian Plantation Forests. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24340 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Lelana NE, Utami S, Darmawan UW, Nuroniah HS, D, A, et al. Bagworms in Indonesian Plantation Forests. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24340. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Lelana, Neo Endra, Sri Utami, Ujang Wawan Darmawan, Hani Sitti Nuroniah, Darwo , Asmaliyah , Noor Farikhah Haneda, Arinana Arinana, Wida Darwiati, Illa Anggraeni. "Bagworms in Indonesian Plantation Forests" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24340 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Lelana, N.E., Utami, S., Darmawan, U.W., Nuroniah, H.S., , D., , A., Haneda, N.F., Arinana, A., Darwiati, W., & Anggraeni, I. (2022, June 22). Bagworms in Indonesian Plantation Forests. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24340

Lelana, Neo Endra, et al. "Bagworms in Indonesian Plantation Forests." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Bagworms are polyphagous, with many hosts; for example, the defoliator P. plagiophleps was found feeding on 22 plant families, in annual crops and perennial trees. Bagworm infestations occur not only in plantation forests but also in natural forests. In many cases, the dynamics of a pest infestation are not well understood. For example, in India, P. plagiophleps, previously known as an insignificant pest of Tamarindus indica L., was involved in outbreaks in 1977 in F. moluccana, followed by Delonix regia (Hook.) Raf. and Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile. Understanding the diversity of bagworms and the factors that influence their development are important for sustainable plantation forest management.

host plant

infestations

Oiketicinae

sustainable forest plantation

Taleporiinae

Typhoniinae

1. Pest Status of Bagworms in Indonesian Plantation Forests

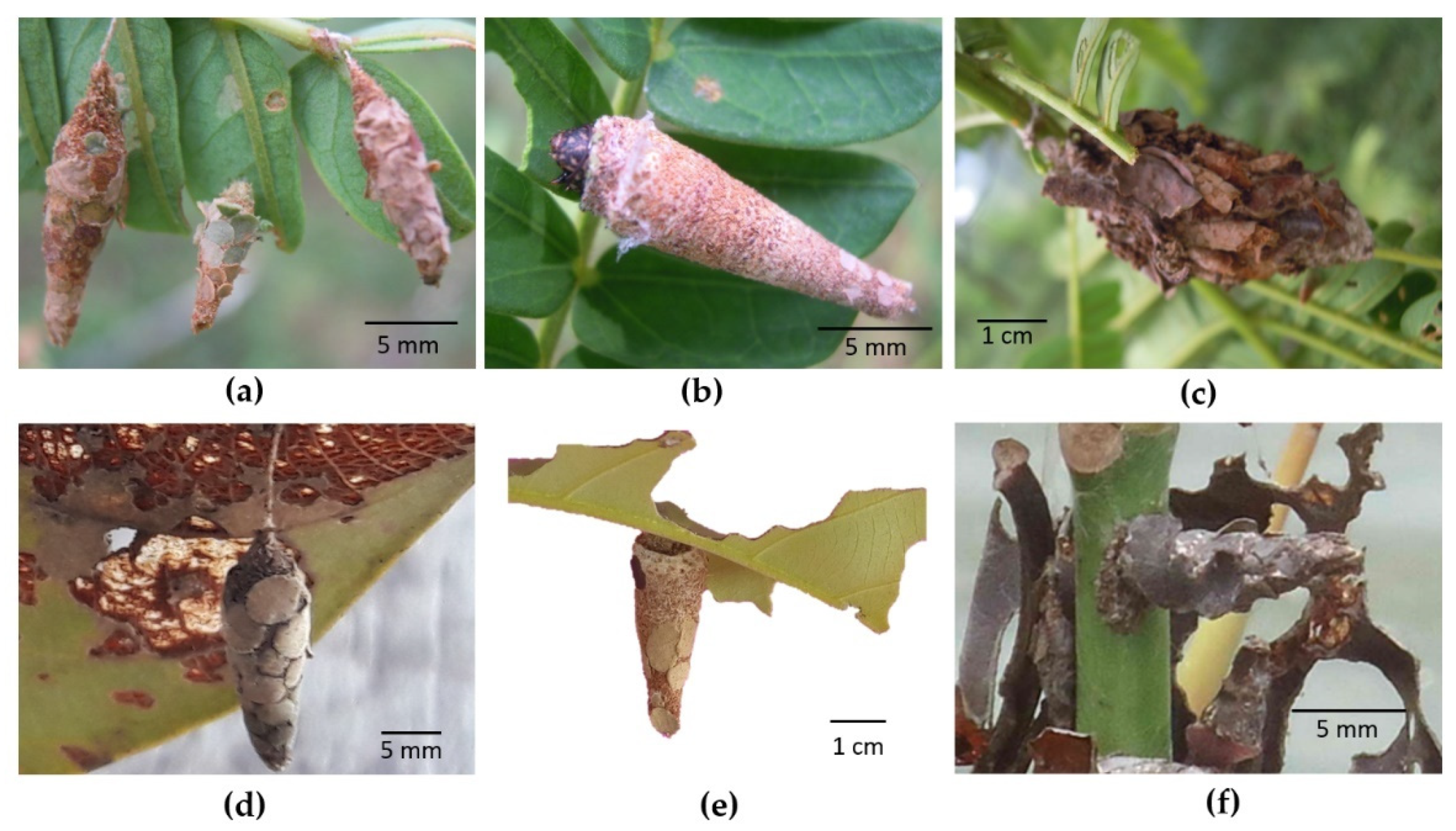

Bagworm species associated with forest trees in Indonesia are presented in Table 1. All these species belong to the subfamilies Metisinae, Psychinae, and Oiketicinae. Their pest status in forest trees varies. Most bagworms are categorized as minor pests. However, some species, such as P. plagiophleps on F. moluccana (Figure 1a) and Acanthopsyche sp. on Shorea leprosula Miq., are major pests [1][2].

Figure 1. Some common bagworm species associated with Indonesian forest trees. Larvae are equipped with a bag as a morphologically unique feature: (a) Falcataria moluccana infested by Pteroma plagiophleps; (b) Falcataria moluccana infested by Amatissa sp.; (c) Falcataria moluccana infested by Cryptothelea sp.; (d) Shorea balangeran infested by Pteroma sp.; (e) Shorea balangeran infested by Cryptothelea sp.; (f) Mangrove infested by Pagodiella sp.

The infestation of bagworms on forest trees has mainly occurred in Fabaceae (especially F. moluccana), Dipterocarpaceae, and mangroves (Table 1). Early symptoms show small feeding holes on the leaves. The color of the leaves turns brown, with leaves eventually drying out completely. The infestation can cause the plant to become partially defoliated and weakened. In cases of severe infestation, complete defoliation may also occur, even following an infestation of the bark [3][4]. On the other hand, bagworms are rarely reported as major pests of eucalyptus and acacia, despite these two commodities being the most dominant species in Indonesian industrial forest plantations [5]. Several reports on bagworm infestations on Acacia mangium Willd. only indicated minor attacks [6][7].

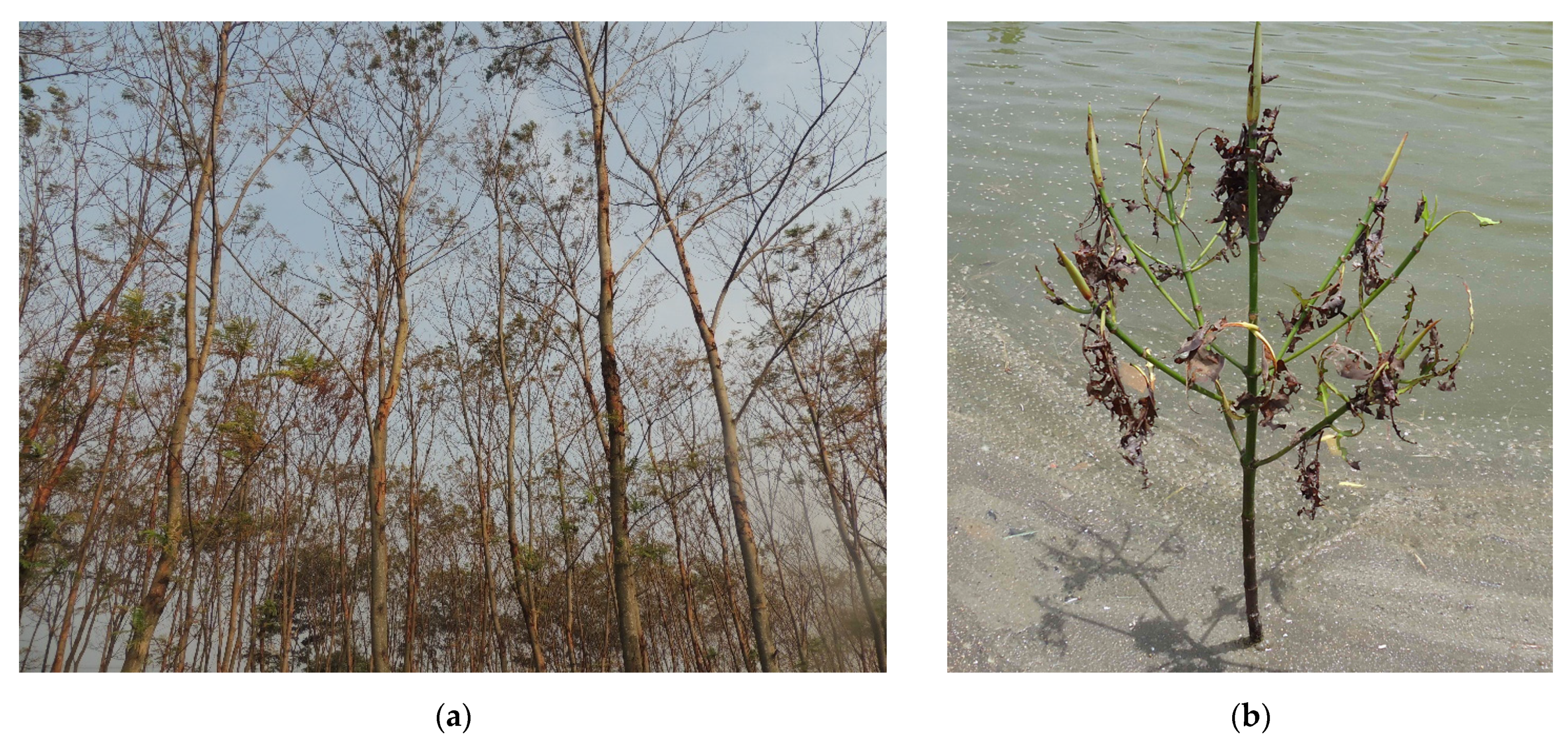

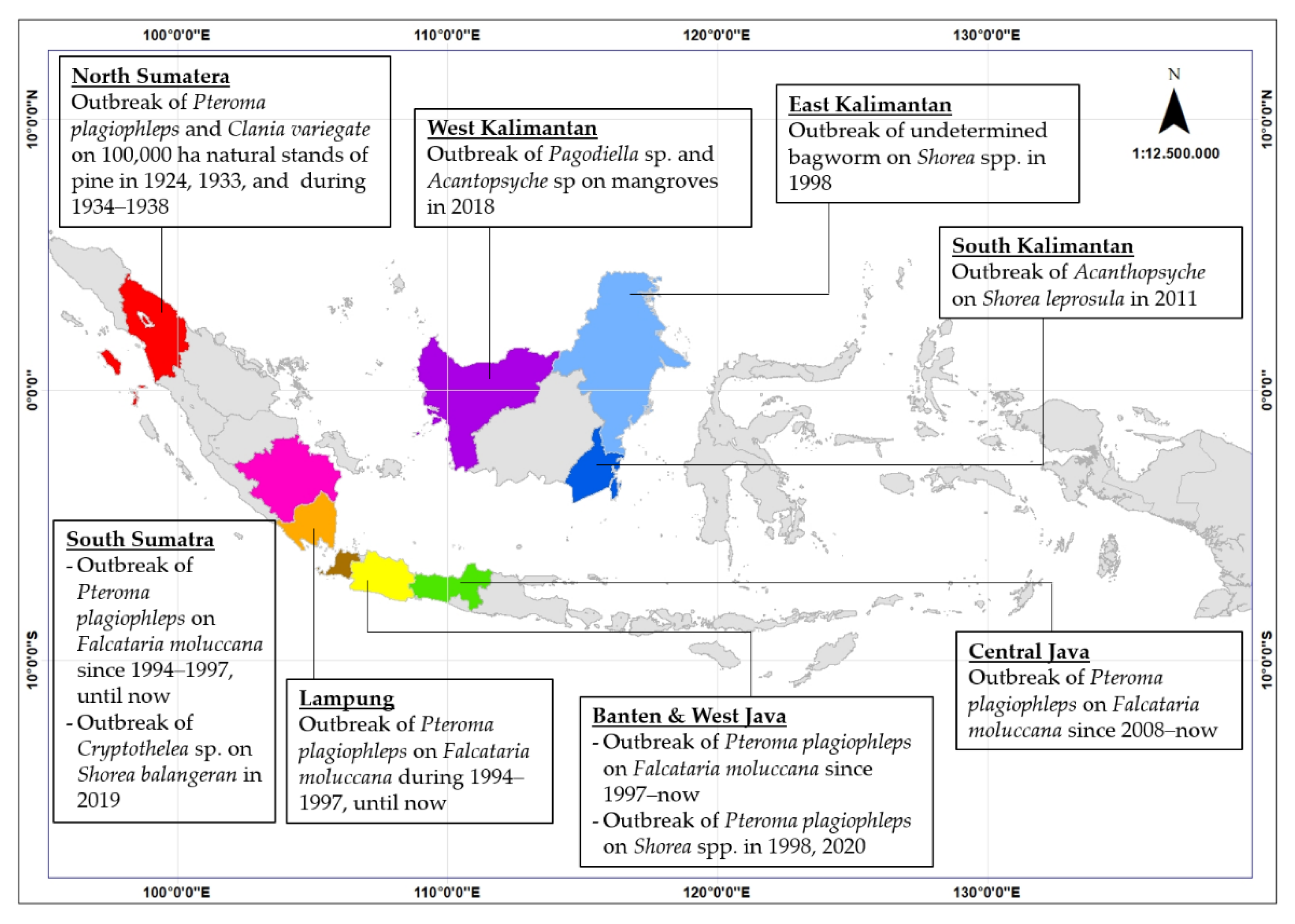

Pteroma plagiophleps, as a member of Metisinae, is considered the most important pest in the forestry sector due to the wide range of forest trees used as hosts. Around 14 forest tree species are recorded as its host (Table 1). Severe infestation of P. plagiophleps occurred on Pinus merkusii Jungh. & de Vriese, F. moluccana (Figure 2a), S. leprosula, and Rhizophora sp. The first record of a P. plagiophleps outbreak was on the natural stands of P. merkusii in North Sumatra in 1924, 1933, and throughout 1934 to 1938 (Figure 3) [8][9][10]. The outbreaks affected approximately 100,000 ha of natural pine stands and caused severe defoliation that continued for months during the outbreak, affecting resin production, especially in the most severely attacked sites [8][10].

Figure 2. Infestation of bagworms in a forest. (a) Condition of F. moluccana stands infested by Pteroma plagiophleps in an F. moluccana plantation in Central Java. Almost all trees were severely defoliated, and some of them were dead. (b) Mangrove tree infested by Pagodiella sp. in Sumatra, with severe defoliation.

Figure 3. Bagworm outbreaks recorded in Indonesia. Most of these cases occurred in Western Indonesia. Different colors indicate the province where the outbreak of bagworms was reported.

Other outbreaks of P. plagiophleps were then reported in other forest trees in different regions in Indonesia, mostly in plantation forests (Figure 3). Pteroma plagiophleps outbreaks occurred in an industrial forest plantation in South Sumatra from 1994 to 1997 [10][11]. It attacked a five-year-old F. moluccana plantation and caused severe defoliation [10][11]. In Java, P. plagiophleps was considered a minor pest until the first outbreak reported in 1997 in F. mollucana and A. mangium plantations in West Java and Banten [6]. A P. plagiophleps outbreak in F. moluccana was then recorded in Central Java in 2008 [1]. Outbreaks affected hundreds of hectares in the F. moluccana plantations, causing severe attacks and plant death [1]. In 2019, infestations continued to occur in Central and West Java [12]. Bagworm outbreaks in Central Java’s F. moluccana plantations are becoming more frequent. Previously, outbreaks only occurred occasionally, but they have become more frequent every year [12].

In S. leprosula, severe infestations of P. plagiophleps were reported over 2–7 years in South Kalimantan [2]. Meanwhile, in mangrove tree Rhizophora sp., severe infestation of P. plagiophleps also occurred on the seedling in Aceh [13]. Pteroma plagiophleps infestations result from unsuccessful factors in mangrove planting, both in natural reforestation and plantation forests [13][14].

Minor infestations of P. plagiophleps were recorded in at least five species of dipterocarp. An infestation of P. plagiophleps on the seedling and plantation of Shorea balangeran Burck was reported in South Sumatra with low severity [15][16]. In West Kalimantan, infestation of P. plagiophleps was reported in S. leprosula with low–moderate severity [17]. In Java, minor infestations of P. plagiophleps were reported in Shorea macrophylla macrophylla (de Vriese) P.S.Ashton, Shorea stenoptera Burck., and Anisoptera sp. seedlings [18]. Furthermore, P. plagiophleps infestations of minor incidence and severity were also reported in other forest trees, such as Azadirachta excelsa (Jack) Jacobs in Bengkulu and South Sumatra [16][19][20], Neolamarckia cadamba (Roxb.) Bosser and Maesopsis eminii Engl. in Lampung [13], and A. mangium in West Java [6][21][22].

Outbreaks of P. plagiophleps in forest trees were also reported in India. The first outbreak of P. plagiophleps in India occurred in 1977 on F. moluccana, D. regia, and A. nilotica [10][23][24]. Infestations of P. plagiophleps were also reported on mangroves [25][26]. Another Pteroma species, P. pendula, has also been considered an important pest. Similar to P. plagiophelps, it has a wide host range [27]. It is the second most destructive bagworm pest of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) in Malaysia and Indonesia [28][29][30]. However, there are no reports of infestation in Indonesian forest trees, although, in Malaysia, it has been reported to infest A. mangium [29].

Other bagworms that cause severe infestation in Indonesian forest trees are Acanthopsyche and Cryptothelea. Akbar [2] reported an outbreak of Acanthopsyche sp. on S. leprosula in South Kalimantan. This species infested 2–7-year-old trees of S. leprosula and caused severe defoliation. An infestation of Acantopsyche sp., together with Pagodiella sp., in Avicennia alba Blume and Bruguiera parviflora (Roxb.) Wight & Arn. ex Griff. caused severe defoliation in sapling levels in West Kalimantan [14].

Cryptothelea is also an important bagworm infesting forest trees. This species is larger than Pteroma sp. or other species of bagworms (Figure 1). This species is commonly found in plantations rather than nurseries. The forest trees recorded as hosts are F. moluccana, Shorea selanica (Lam.) Blume, and S. balangeran. Generally, these bagworms are found in low population densities with other bagworm species [1][6]. Cryptothelea infestation in S. balangeran on peatland in Sumatra showed low severity [31]. However, repeated attacks can exacerbate the severity [15]. Attacks of Cryptothelea are also known in Avicennia sp. and Bruguiera sp. in Riau [32]. In pines, the outbreak of Cryptothelea variegata Snellen (1879) has been reported in a few instances [10].

Pagoda bagworms, Pagodiella sp., are often found in mangrove trees, both in nurseries and plantations (Figure 1) [33][34]. Pagodiella sp. sometimes causes severe damage to mangrove trees (Figure 2b). The attacks of Pagodiella sp. in West Kalimantan caused moderate–severe damage [14]. In Malaysia, Pagodiella sp. was also reported to cause severe defoliation [35]. Other forest trees that can host Pagodiella sp. are N. cadamba, A. excelsa, and Michelia champaca L. The level of infestation and severity is still relatively low [36]. Pagodiella sp. was also considered a severe pest of oil palm in Malaysia [37]. This pest has also attacked the Myrtaceae family [9].

Table 1. List of bagworm species associated with Indonesian forest trees.

| Bagworm Species | Host Plant | Host Stage | Level of Damage | Location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pteroma plagiophleps | Falcataria moluccana | seedling, tree | minor–severe | Java, Sumatra | [1][12][13][24][38] |

| Acacia mangium | tree | minor | Java, Sumatra | [6][21][22] | |

| Rhizophora sp. | tree | severe | Sumatra | [39] | |

| Soneratia caseolaris | tree | minor | Sumatra | [40] | |

| Shorea leprosula | seedling, tree | minor–severe | Java, Kalimantan, Sumatra | [16][17] | |

| Shorea balangeran | tree | minor | Sumatra | [15] | |

| Shorea macrophylla | seedling | minor | Java | [18] | |

| Shorea stenoptera | seedling | minor | Java | [18] | |

| Anisoptera sp. | seedling | minor | Java | [18] | |

| Azadirachta excelsa | seedling, tree | minor | Sumatra | [16][19] | |

| Neolamarckia cadamba | tree | minor | Sumatra | [13] | |

| Maesopsis eminii | tree | minor | Sumatra | [13] | |

| Pinus merkusii | tree | severe | Sumatra | [9][10][41] | |

| Acanthopsyche sp. | Avicennia alba, Bruguiera parvifolia | tree | minor–moderate | Kalimantan | [14] |

| Shorea leprosula | tree | moderate–severe | Kalimantan | [20] | |

| Clania sp. | Falcataria moluccana | Seedling, tree | minor–severe | Java, Kalimantan | [12][42][43] |

| Cryptothelea sp. | Falcataria moluccana | Seedling, tree | minor–severe | Java | [1][12][42][43] |

| Pinus merkusii | tree | severe | Sumatra | [41] | |

| Shorea selanica | tree | minor | Kalimantan | [44] | |

| Avicenia sp. | tree | n.a. | Sumatra | [32] | |

| Bruguiera sp. | tree | n.a. | Sumatra | [32] | |

| Shorea balangeran | seedling, tree | minor | Sumatra | [15][33] | |

| Mahasena corbeti | Neolamarckia cadamba | tree | moderate | Sumatra | [45] |

| Metisa plana | Shorea balangeran | seedling, tree | minor | Sumatra | [15][33] |

| Anisoptera marginata | seedling | minor | Sumatra | [46] | |

| Pagodiella sp. | Avicennia alba, Bruguiera parviflora | tree | minor–moderate | Kalimantan | [14] |

| Rhizophora apiculata | seedling | minor | Sumatra, Sulawesi | [33][34] | |

| Neolamarckia cadamba | tree | minor | Sumatra | [36] | |

| Azadirachta excelsa | tree | minor | Sumatra | [36] | |

| Michelia champaca | tree | minor | Sumatra | [36] | |

| Amatissa sp. | Falcataria moluccana | seedling, tree | minor–severe | Java, Kalimantan | [1][6][42][43] |

| Chalia javana | Falcataria moluccana | tree | minor | Java | [12] |

| Kophenecuprea | Falcataria moluccana | tree | minor | Java | [12] |

| Psyche sp. | Falcataria moluccana | tree | severe | Java | [6] |

| Acacia mangium | tree | n.a. | Java | [6] |

Remark: n.a: not assessed.

Three major bagworm pests (M. plana, P. pendula, and M. corbetti) in oil palm [37][45][47][48][49][50][51][52] were also found in Indonesian forest trees. However, infestation was still at a minor–moderate level. Infestation of M. plana was reported in S. balangeran in South Sumatra at a minor to moderate level [31]. Metisa plana has been found in the dipterocarp Anisoptera marginata Korth nursery and caused moderate damage [46]. Similarly, M. corbetti has attacked N. cadamba stands with moderate damage in Sumatra [45]. The diffusion of this bagworm should be monitored because forest trees around oil palm plantations can act as alternative hosts [53].

In addition to the bagworm species mentioned previously, several other bagworm species, including Amatissa sp., Chalia javana Heylaerts, 1885, Kophene cuprea Moore, 1879, and Psyche sp., were reported to be associated with F. moluccana plants, except Psyche, which is also found in A. mangium [1][6][12][22][43]. An unidentified bagworm was also reported in Shorea spp. in East Kalimantan and specifically on S. leprosula and S. selanica in West Java [41][54].

In Indonesia, bagworm outbreaks on forest trees have been recorded on three main islands: Java, Sumatra, and Kalimantan (Figure 3). This may relate to the distribution of plantation forests, which are mostly concentrated on these three islands [5]. Other bagworm attacks have occurred in mangrove stands in Sulawesi [34]. Outbreaks of bagworms are no less important than those of other pests. Although no economic loss data have been reported on Indonesian forest trees, reports on oil palm plantations can provide an overview of the impact of bagworm outbreaks. Wood et al. [55] reported crop losses in oil palm up to 40–50% due to severe defoliation caused by bagworms in Malaysia. Another study on oil palm also reported that approximately 40% of crop losses were due to bagworm outbreaks [56][57].

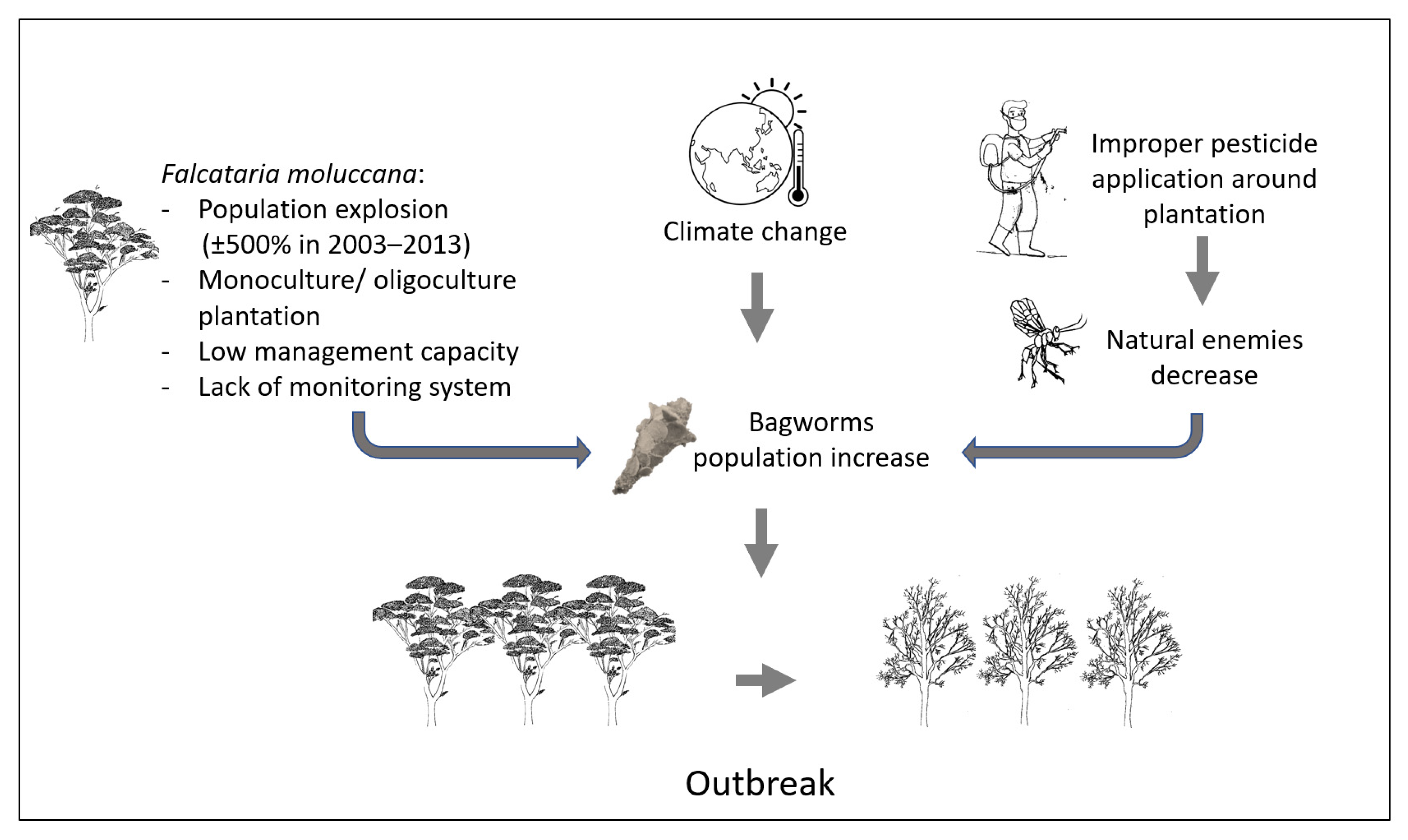

2. The Key Factors That Lead to Bagworm Outbreaks in Indonesian Plantation Forests

The population dynamics of bagworms are not fully understood. Populations are usually maintained at a low level, but they can increase sharply in a short time under particular conditions. Nair and Mathew [24] categorized the level of bagworm infestation into three types: (1) sparse infestations (bagworm infestations that occur with a low number of bagworm populations in most host plants); (2) dense infestations (bagworm infestations that occur in isolated and individual plants); and (3) heavy outbreaks (large-scale bagworm infestations that affect many plants in a patch, e.g., in F. moluccana and A. nilotica). Outbreaks can also occur in other tree species that are not a primary host of bagworm. For instance, a bagworm outbreak occurred in Eucalyptus tereticornis Sm. in a location polluted by sulfur dioxide, despite this tree not being the primary host of the bagworm [58]. Therefore, host stress has been indicated as a predisposing factor for bagworm outbreaks [10].

2.1. Reproductive Strategy and Mode of Dispersal

The life cycle and fecundity of bagworms significantly influence the occurrence of bagworm outbreaks [27][59][60]. The fecundity of bagworms varies greatly depending on the species. Small-sized bagworms such as Psyche, Pteroma, and M. plana produce fewer eggs than large-sized species, such as Eumeta variegate (Snellen, 1879) and Eumeta crameri (Westwood), 1854. However, M. corbetti, categorized as a smaller-sized bagworm, produces a large number of eggs [27].

The body size and the developmental phase of the bagworms affect the preferences of natural enemies in finding hosts. Parasitoids avoid small and early stage bagworms [61]. Some large parasitoids, such as Xanthopympla sp., and tachinid flies prefer Cryptothelea crameri (Westwood), 1854 as a host compared to other smaller bagworms, such as P. plagiophleps [12]. In Java, outbreaks of P. plagiophleps in F. moluccana are more common than Cryptothelea. The Cryptothelea population affecting F. moluccana is always low, even though the fecundity is high. Furthermore, P. plagiophleps outbreaks often occur, even though their fecundity is lower [12][27].

The short life cycle significantly influences the incidence of bagworm outbreaks. For instance, outbreaks can occur more easily in P. pendula than in M. plana; this is due to the shorter life cycle of P. pendula compared with M. plana. The life cycles of P. pendula and M. plana range from 48 to 50 days and 92 to 97 days, respectively, whereas their number of generations is eight and three, respectively [60].

Dispersal strongly impacts population dynamics, and it is the most important factor influencing population size [62][63]. The different dispersal modes among bagworm species influence the incidence of outbreaks [59].

2.2. Climate

Climatic factors affecting the development of bagworms are temperature and rainfall. Increasing temperature accelerates the rate of pest consumption, development, and mobility, as well as fecundity, survival, generation time, population density, and geographic range [64]. Pest metabolism tends to increase twofold with an increase in temperature of 10 °C [64]. An increase of 2 °C can cause pests to experience five life cycles per year [64]. Temperature affects the development time of reproduction and the fecundity of the bagworm Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis (Haworth, 1803) [65][66]. An increase in air temperature over the usual values induces a shorter life cycle and higher fecundity in T. ephemeraeformis [65][66][67].

Rainfall also affects the behavior and survival of bagworms. Rainfall had a more deleterious effect on the population of M. plana than P. pendula due to the greater ballooning habits of neonate larvae [68]; this explains why P. pendula is more resistant to wet weather and can initiate outbreaks early in dry periods [67]. In the case of bagworm outbreaks in F. moluccana stands in Java, rainfall significantly influences their population dynamics [12]. When the rainfall is high during the rainy season, the bagworm population decreases because the heavy rain causes the bagworms attached to F. moluccana leaves to fall away [12].

The diversity, abundance, and distribution of natural enemy populations affect bagworm populations [57][69]. Environmental factors such as light intensity, temperature, and relative humidity affect the diversity and activity of bagworms’ natural enemies. Natural enemies (hymenopterous parasitoids and reduviid predatory insects) of bagworms in oil palm plantations are significantly more active under conditions of moderate light intensity (<8000 fc), medium humidity levels (50–69%), and medium temperatures (30–34 °C) [68].

2.3. Monoculture Plantation

There are two management forms in small-holder forest plantations, a complex agroforestry system and a monoculture system [70]. The first form of agroforestry combines forest trees with some fruit trees, creating a mixed-species plantation. The second form of agroforestry combines forest trees with crops/horticulture and crops. Referring to species composition, the second form is a mixed-species plantation; however, its stand structure is classified as a monoculture.

The presence and abundance of host plants are supporting factors for bagworm outbreaks. The monoculture pattern is considered an efficient cultivation practice to increase productivity. However, monoculture also increases the risk of pest population outbreaks [62]. Large-scale monoculture stands provide an abundant food source to support large bagworm populations. Low plant species diversity in monocultures encourages the development of pest populations [71]. Host abundance and low natural enemy abundance in monoculture patterns, accompanied by host suitability, are more likely to trigger outbreaks [72].

Host plants influence the biological performance of bagworms, such as the outbreak of P. plagiophleps on F. moluccana plants in several areas of Java (Figure 4). Although polyphagous, P. plagiophleps shows differences in life cycle performance in other hosts. Other research has shown how food quality and environmental conditions affect the rate of bagworm development [12][73]. In addition, the quality of the host plant changes the insect’s reproductive strategy, through factors such as size, egg quality, and oviposition behavior [74].

Figure 4. Schematic of Pteroma plagiophleps outbreak in a Falcataria moluccana plantation.

The simplified ecosystem in plantation forests appears sensitive to natural disturbance [75]. Therefore, using mixed species in plantation forests may be an attractive alternative to achieve sustainability goals. Previous research showed that the disturbance caused by insect pests in forestry systems is lower in more diversified ecosystems than in simplified ecosystems [76][77][78][79][80][81].

Two classic hypotheses have been proposed to explain the mechanism of decreasing insect pest populations in diversified ecosystems [82][83][84][85]. The first mechanism, the so-called “resource concentration hypothesis”, explains that a decreasing insect pest population is caused by decreasing pest immigration and increasing pest emigration. A diversified ecosystem with non-host trees causes signal disruption of visual and olfactory cues and triggers the pest to leave. The second mechanism, known as the “enemies hypothesis”, postulates that a decreasing insect pest population occurs due to increasing natural enemies. A diversified ecosystem provides better shelter opportunities and prey resources for natural enemies. Some previous studies showed that the diversity and abundance of natural enemies in mixed plantations are higher than in monocultures [86][87].

2.4. Cultivation Practices

Cultivation practices affecting bagworm outbreaks include planting patterns and insecticide application. Monocultures can cause outbreaks, as described above. The use of chemical insecticides directly affects the potential for outbreaks in bagworms. Inappropriate use of synthetic chemical insecticides with a broad spectrum negatively impacts natural enemies as they are more susceptible to insecticides [59]. Chemical control should only be conducted if the bagworm population reaches the threshold; if the bagworm’s life cycle is known, the control will be effective. Furthermore, the application should be performed with the correct dose, at the appropriate time [59].

2.5. Natural Enemies

The presence of natural enemies plays an important role in controlling bagworm populations in oil palm plantations [60][88]. Predators, parasitoids, and some entomopathogenic fungi significantly contribute to the mortality of P. pendula and M. plana in oil palm plantations [30][60][88][89]. Four species of parasitoids were recorded attacking P. pendula in an oil palm plantation, namely, Pediobius imbrues Walker (1846) (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), Pediobius elasmi (Ashmead, 1904) (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), Dolichogenidea metesae (Nixon, 1967) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), and Aulosaphes psychidivorus Muesebeck, 1935 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) [30]. In M. plana, the recorded parasitoids were D. metesae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Apanteles aluaella (Nixon, 1967) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Aulosaphes psychidivorus Muesebeck, 1935 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Buysmania oxymora (Tosquinet, 1903) (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae), Goryphus bunoh Gauld, 1987 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Brachymeria carinata Joseph, Narendran & Joy, 1970 (Hymenoptera: Chalcididae), Elasmus sp. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), Sympiesis sp. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), and Tetrastichus sp. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) [61]. Callimerus arcufer Chapin, 1919 (Coleoptera: Cleridae) larvae and Cosmolestes picticeps (Stal, 1859) (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) were common predators found to attack P. pendula [60]. Two species of entomopathogenic fungi affected bagworm populations in oil palm plantations, namely, Paecilomyces fumosoroseus (Wize) A.H.S. Br. & G. Sm. (1957) and Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschn.) Sorokīn (1883) [30][60].

References

- Gullan, P.J.; Cranston, P.S. The Insects: An Outline of Entomology; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 6–10.

- Akbar, A. Identifikasi jenis-jenis hama dan penyakit pada meranti merah (Shorea leprosula Miq) di Pulau Laut, Kalimantan Selatan. In Proceedings of the Dukungan BPK Banjarbaru Dalam Pembangunan Kehutanan di Kalimantan, Prosiding Ekspose Hasil Penelitian Balai Penelitian Kehutanan Banjarbaru, Banjarbaru, Indonesia, 25–26 October 2011; Balai Penelitian Kehutanan Banjarbaru: Banjarbaru, Indonesia, 2011; pp. 213–223.

- Chung, G.F. Effect of pests and diseases on oil palm yield. In Palm Oil: Production, Processing, Characterization, and Uses; Lai, O.M., Tan, C.P., Akoh, C.C., Eds.; AOCS Press: Urbana, OH, USA, 2012; pp. 163–210.

- Appleton, M.R.; van Staden, J. Bagworms (Lepidoptera: Psychidae): Potential pest of guayule (Parthenium argentatum Gray) plantations in southern Africa. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 1992, 9, 159–162.

- BPS-Statistics Indonesia. Statistics of Timber Culture Establishment 2019; BPS: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020.

- Suharti, M.; Sitepu, I.R.; Darwiati, W.; Anggraeni, I. Uji efikasi beberapa agens pengendali biologi, nabati dan kimia terhadap hama ulat kantong. Bull. Penelit. Hutan 2000, 624, 11–28.

- Frank, S.D. A survey of key arthropod pests on common southeastern street trees. Arboric Urban For. 2019, 45, 155–166.

- Nair, K.S.S. Insect pests and diseases for major plantation species. In Insect Pests and Diseases in Indonesia Forests: An Assessment of the Major Threat, Research Efforts and Literature; Nair, K.S.S., Ed.; Centre for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2000.

- Kalshoven, L.G.E. Important Outbreak of Insect Pest in the Forest of Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Transactions of the 9th International Congress of Entomology, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 17–24 August 1951; Junk, W., Ed.; Hague, The Netherlands, 1953; Volume 2, pp. 229–234.

- Nair, K.S.S. Tropical Forest Insect Pest, Ecology, Impact, and Management; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- Zulfiyah, A. Pest problems and threat in industrial plantation forests at PT Musi Hutan Persada, South Sumatra. In Proceedings of the Workshop Permasalahan dan Strategi Pengelolaan Hama di Areal Hutan Tanaman, Central Java, Indonesia, 17–19 June 1997; Suratmo, F.G., Hadi, S., Husaeni, E.A., Rahmatsjah, O., Kasno Nuhamara, S.T., Haneda, N.F., Eds.; Fakultas Kehutanan dan Departemen Kehutanan: West Java, Indonesia, 1998.

- Darmawan, U.W.; Triwidodo, H.; Hidayat, P.; Haneda, N.F.; Lelana, N.E. Bagworms and their natural enemies associated with albizia (Falcataria moluccana (Miq.) Barneby & J.W. Grimes plantation. J. Penelit. Hutan Tanam. 2020, 17, 296–307.

- Surachman, I.F.; Indriyanto, I.; Hariri, A.M. Inventarisasi hama persemaian di hutan tanaman rakyat desa Ngambur Kecamatan Bengkunat Belimbing Kabupaten Lampung Barat. J. Sylva Lestari 2004, 2, 7–16.

- Haneda, N.F.; Suheri, M. Mangrove pests at Batu Ampar, Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan. J. Silvikultur Trop. 2019, 9, 16–23.

- Budiman, I.; Bastoni, B.; Sari, E.N.; Hadi, E.E.; Asmalyah, A.; Siahaam, H.; Januar, R.; Hapsari, R.D. Progress of paludiculture projects in supporting peatland ecosystem restoration in Indonesia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01084.

- Priatna, D.; Utami, S. Beberapa jenis hama yang menyerang bibit tanaman hutan di persemaian. In Proceedings of the Serangga Untuk Pertanian Berkelanjutan Dan Kesehatan Lebih Baik, Prosiding Seminar Nasional PEI Cabang Palembang, Palembang, Indonesia, 12–13 July 2018; Herlinda, S., Ed.; Perhimpunan Entomologi Indonesia: Bogor, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 203–211.

- Abi Oramahi, H.; Wulandari, S.R. Identifikasi morfologi serangga berpotensi sebagai hama dan tingkat kerusakan pada bibit meranti merah (Shorea leprosula). J. Hutan Lestari. 2017, 5, 644–652.

- Darwiati, W.; Anggraeni, I.; Intari, S.E. Serangan ulat kantong pada bibit meranti di persemaian. Info. Hutan. 2005, 2, 345–351.

- Utami, S.; Anggraeni, I. Serangan Hama Ulat Kantong (Pteroma plagiophleps) pada Tanaman Kayu Bawang (Dysoxylum Mollissimun Blume) di Persemaian dan Lapangan. In Peran dan Tantangan Entomologi di Era Global, Proceedings of the Kongres VIII Dan Seminar Nasional Perhimpunan Entomologi Indonesia, Bogor, Indonesia, 24–25 January 2012; Pudjianto, D., Laba, I.W., Eds.; Perhimpunan Entomologi Indonesia: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014; pp. 207–216.

- Utami, S.; Kurniawan, A. Potensi hama pada pola agroforestri kayu bawang di Provinsi Bengkulu. In Agroforestry Untuk Pangan dan Lingkungan yang Lebih Baik, Prosiding Seminar Nasional Agroforestri, Malang, Indonesia, 21 May 2013; Kuswantoro, D.P., Widyaningsih, T.S., Fauziyah, E., Rachmawati, R., Eds.; Kerjasama Balai Penelitian Teknologi Agroforestry, Fakultas Pertanian Universitas Brawijaya, World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), dan Masyarakat Agroforestri Indonesia: Malang, Indonesia, 2013; pp. 197–303.

- Nair, K.S.S. Pest Outbreak in Tropical Forest Plantations. Is There a Greater Risk for Exotic Tree Species; Center for International Forestry Research: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2001.

- Tiffani, N.A.; Ramdan, H.; Dungani, D. The characteristics of Acacia mangium stands at site 23B, RPH Maribaya, BKPH Parung Panjang, KPH Bogor, which is attacked by pest and diseases. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 528, 12043.

- Pillai, S.R.M.; Gopi, K.C. The bagworm Pteroma plagiophleps Hamp. (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) attack on Acacia nilotica (Linn.) Wild. ex del. Indian For. 1990, 116, 581–583.

- Nair, K.S.S.; Mathew, G. Biology, Infestation characteristics and impact of the bagworm, Pteroma plagiophleps Hamps in forest plantations of Paraserianthes falcataria. Entomon 1992, 17, 1–13.

- Tripathy, M.K.; Parida, G.; Behera, M.C. Diversity of insect pests and their natural enemies infesting sal (Shorea robusta Garten f.) in Odisha. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2020, 8, 1812–1822.

- Santhakumaran, L.N.; Remadevi, O.K.; Sivaramakrishnan, V.R. A new record of the insect defoliator Pteroma plagiophleps Hamp. (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) from mangrove along the Goa coast (India). Indian For. 1995, 12, 153–155.

- Rhainds, M.; Davis, D.R.; Price, P.W. Bionomics of bagworms (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2008, 54, 209–226.

- Basri, M.W. Life History, Ecology and Economic Impact of the Bagworm, Metisa plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Psychidae), on the Oil Palm, Elaeis guineensis Jacquin (Palmae), in Malaysia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 1993; p. 231.

- Cheong, Y.L.; Sajap, A.S.; Noor, H.M.; Omar, D.; Abood, F. Demography of the bagworm Pteroma pendula Joannis on an exotic tree Acacia mangium wild in Malaysia. Malaysian For. 2010, 73, 77–85.

- Cheong, Y.L.; Sajap, A.S.; Hafidzi, M.N.; Omar, D.; Abood, F. Outbreaks of bagworm and their natural enemies in an oil palm, Elaeis guineensis, Plantation at Hutan Melintang Perak, Malaysia. J. Entomol. 2010, 7, 141–151.

- Asmaliyah, A.; Hadi, E.E.W.; Irianto, S.B.; Imanullah, A.; Bastoni, B.; Siahaan, H.; Purwanto, P. Bagworm infestation on Shorea balangeran in the degraded peatland restoration plot. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 533, 12041.

- Hardi, T.W.; Siringoringo, H.H. Identifikasi hama mangrove dan pengendaliannya dengan bakteri. Bull. Penelit. Hutan 2000, 621, 55–64.

- Asmaliyah, A.; Anggraeni, I. Uji aplikasi beberapa bioinsektisida dan kombinasinya terhadap serangan hama ulat kantong Pagodiella sp. pada bibit Rhizophora apiculata di persemaian. J. Penelit. Hutan Tanam. 2009, 6, 37–43.

- Wahid, A. Efikasi bioinsektisida dan kombinasinya pada bibit mangrove Rhizophora spp. di persemaian. Agroland 2010, 17, 162–168.

- Ong, S.P.; Cheng, S.; Chong, V.C.; Tan, Y.S. Pest of Planted Mangroves in Peninsular Malaysia; Toh, A.N., Ed.; Forest Research Institute Malaysia: Selangor, Malaysia, 2010.

- Utami, S.; Kurniawan, A. Hama Penting pada Tegakan Hutan dan Letak Pengendaliannya di KHDTK Kemampo Sumetera Selatan. In Serangga untuk Pertanian Berkelanjutan dan Kesehatan Lebih Baik, Proceedings of the Seminar Nasional PEI Cabang Palembang, Palembang, Indonesia, 12–13 July 2018; Herlinda, S., Ed.; Perhimpunan Entomologi Indonesia: Bogor, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 404–414.

- Lee, C.Y. Urban Forest insect pests and their management in Malaysia. Formosan Entomol. 2014, 33, 207–2014.

- Utami, S.; Haneda, N.F. Bioaktivitas ekstrak umbi gadung dan minyak nyamplung sebagai pengendali hama ulat kantong (Pteroma plagiophleps Hampsin). J. Penelit. Hutan Tanam. 2012, 9, 209–218.

- Dewiyanti, I.; Yunita, Y. Identifikasi dan kelimpahan hama penyebab ketidakberhasilan rehabilitasi ekosistem mangrove. Ilmu Kelaut. 2013, 18, 150–156.

- Utami, S.; Lelana, N.E.; Kunarso, K.; Kurniawan, A.; Haneda, N.F. Pests of Sonneratia caseolaris seedlings in the mangrove restoration area nursery of Berbak-Sembilang National Park and its damage. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Indonesia Forestry Researchers (INAFOR): Managing Forest and Natural Resources Meeting Sustainable and Friendly Use, Bogor, Indonesia, 7−8 September 2021; Earth and Environmental Science: Bristol, UK; Volume 914, p. 12019.

- Morgan, F.D.; Suratmo, F.G. Host Preferences of Hypsipyla robusta (Moore) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in West Java. Aust. For. 1976, 39, 103–112.

- Anggraeni, I.; Ismanto, A. Keanekaragaman jenis ulat kantong yang menyerang di berbagai pertanaman sengon (Paraserianthes falcataria (L.) Nielson) di Pulau Jawa. J. Sains Nat. Univ. Nusa Bangsa 2013, 3, 184–192.

- Haerumi, W.; Suryantini, R.; Herawatiningsih, R. Identifikasi dan tingkat kerusakan oleh serangga perusak pada bibit sengon (Falcataria moluccana) di persemaian permanen Balai Pengelolaan Daerah Aliran Sungai dan Hutan Lindung Kapuas Pontianak. J. Hutan Lestari 2019, 7, 349–362.

- Manya, M. Inventarisasi serangan hama anakan meranti merah (Shorea selanica) di lokasi CIMTROP Universitas Palangka Raya, Kalimantan Tengah. Agrisilvika 2017, 1, 6–13.

- Sudarsono, H.; Purnomo, P.; Hariri, A.M. Population assessment and appropriate spraying technique to control the bagworm (Metisa plana Walker) in North Sumatra and Lampung. Agrivita 2011, 33, 188–198.

- Zeni, S.A.; Rachmawati, N.; Fitriani, A. Frekuensi dan intensitas serangan hama penyakit pada bibit mersawa (Anisoptera marginata Korth) di persemaian BP2LHK Banjarbaru Kalimantan Selatan. J. Sylva Sci. 2021, 4, 339–345.

- Sankaran, T. The oil palm bagworms of Sabah and the possibilities of their biological control. PANS Pest Artic. News Summ. 1970, 16, 43–55.

- Wood, B.J.; Kamarudin, N. Bagworm (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) infestation in Centennial of the Malaysian oil palm industry—A review of causes and control. J. Oil Palm Res. 2019, 31, 364–380.

- Tuck, H.C.; Ibrahim, Y.; Chong, K.K. Infestation by the bagworms Metisa plana and Pteroma pendula for the period 1986–2000 in major oil palm estates managed by golden hope plantation berhad in Peninsular Malaysia. J. Oil Palm Res. 2011, 23, 1040–1050.

- Halim, M.; Aman-Zuki, A.; Ahmad, S.Z.S.; Din, A.M.M.; Rahim, A.A.; Masri, M.M.M.; Md Zain, B.N.; Yaakop, S. Exploring the abundance and DNA barcode information of eight parasitoid waps species (Hymenoptera), the natural enemies of important pest of oil palm, bagworms, Metisa plana (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) toward the biocontrol approach and its application in Malaysia. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2018, 21, 1359–1365.

- Halim, M.; Ahmad, S.Z.S.; Din, A.M.M.; Yaakop, S. The diversity and abundance of potential Hymenopteran parasitoids assemblage associated with Metisa plana (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) in three infested oil palm plantations in Peninsular Malaysia. AIP Conf. Proceeding 2019, 2111, 060024.

- Priwiratama, H.; Rozziansha, T.A.P.; Prasetyo, A.E.; Susanto, A. Effect of bagworm Pteroma pendula Joannis attack on the decrease in oil palm productivity. J. Hama Dan Penyakit Tumbuh. Trop. 2019, 19, 101–108.

- Kamarudin, N.; Robinson, G.S.; Wahid, M.B. Common bagworm pests (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) of oil palm in Malaysia with notes on related South east Asian species. Malay. Nat. J. 1994, 48, 93–123.

- Rahayu, S.; Subyanto, S.; Kuswanto, K. The occurrence of pest and disease of Shorea spp.: A preliminary study in Wanariset and Bukit Soeharto Forest Area in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Seminar on Ecological Approach for Productivity and Sustainability of Dipterocarp Forests, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 7–8 July 1998; Sabarnudin, H.M.S., Suhardi, S., Okimori, Y., Eds.; Gajah Mada University and Kansai Environmental Engineering Center: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 1998; pp. 53–57.

- Wood, B.; Corley, R.; Goh, K. Studies on the effect of pest damage on oil palm yield. In Advance in Oil Palm Cultivation; Wastie, R.L., Earp, D.A., Eds.; The Incorporated Society of Planters: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1973; pp. 360–379.

- Basri, M.W.; Kevan, P.G. Life History and feeding behavior of the oil palm bagworm Metisa plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Elaeis 1995, 7, 18–34.

- Kamarudin, N.; Wahid, M.B. Interactions of the bag worm, Pteroma pendula (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) and its natural enemies in an oil palm plantation in perak. J. Oil Palm Res. 2010, 22, 758–764.

- Balai Pemantapan Kawasan Hutan XI Jawa-Madura. Strategi Pengembangan Pengelolaan dan Arahan Kebijakan Hutan Rakyat di Pulau Jawa; Balai Pemantapan Kawasan Hutan XI Jawa-Madura: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2009.

- Cheong, Y.L.; Tey, C.C. Enviromental Factors which Influence Bagworm Outbreak. In Proceedings of the 5th MPOB dan IOPRI International Seminar: Sustainable Management of Pests and Disease in Oil Palm—The Way Forward, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–23 November 2013; Malaysian Palm Oil Board: Selangor, Malaysia, 2013.

- Wood, B.J.; Kamarudin, N. A review of developments in integrated pest management (IPM) of bagworm (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) infestation in oil palms in Malaysia. J. Oil Palm Res. 2019, 31, 529–539.

- Ellis, J.A.; Walter, A.D.; Tooker, J.; Ginzel, M.; Reagel, P.F.; Lacey, E.S.; Bennett, A.; Grossman, E.M.; Hanks, L. Conservation biological control in urban landscapes: Manipulating parasitoids of bagworm (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) with flowering forbs. Biol. Control 2005, 34, 99–107.

- Rhainds, M.; Gries, G.; Ho, C.T.; Chew, P.S. Dispersal by bagworm larvae, Metisa plana: Effects of population density, larval sex, and host plant attributes. Ecol. Entomol. 2002, 27, 204–212.

- Denno, R.F.; Peterson, M.A. Density-dependent dispersal and its consequences for population dynamics. In Population Dynamics: New Approaches and Synthesis; Cappuccino, N., Price, P.W., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; p. 113130.

- Skendžic, S.; Zovko, M.; Živkovic, I.P.; Lešic, V.; Lemic, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440.

- Barbosa, P.; Waldvogel, M.G.; Breisch, N.L. Temperature modification by bags of the bagworm Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Can. Entomol. 1983, 115, 855–858.

- Smith, M.P.; Barrows, E.D. Effects of larval case size and host plant species on case internal temperature in the bagworm, Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 1991, 93, 834–838.

- Ibrahim, Y.; Tuck, H.C.; Chong, K.K. Effects of temperature on the development and survival of the bagworms Pteroma pendula and Metisa plana (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). J. Oil Palm Res 2013, 25, 1–8.

- Ho, C.T. Ecological Studies of Pteroma Pendula Joannis and Metisa Plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Psycidae) towards Improved Integrated Management of Infestation Oil Palm. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia, 2002.

- Kamarudin, N.; Arshad, O. Diversity and activity of insect natural enemies of the bagworm (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) within an oil palm plantation in perak, Malaysia. J. Oil Palm 2016, 28, 296–307.

- Sanudin, S.; Fauziah, E. Characteristic of private forest based on its management orientation: Case study in Sukamaju Village, Ciamis District and Kiarajangkung Village, Tasikmalaya District, West Java. Pros. Sem. Nas. Masy. Biodiv. Indon. 2015, 1, 696–701.

- Liu, C.L.C.; Kuchma, O.; Krutovsky, K.V. Mixed species versus monocultures in plantation forestry: Development, benefits, ecosystem services and perspectives for the future. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 15, e00419.

- Staab, M.; Schuldt, A. The influence of tree diversity on natural enemies-a Review of the “enemies” hypothesis in Forests. Curr. For. Rep. 2020, 6, 243–259.

- Fernando, I.V.S.; Jayakody, D.S. Some Aspects of the biology of Pteroma plagiophleps Hampson (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) a defoliator of Delonix regia (Boj) (Leguminosae: Caesalpiniaceae). In Proceedings of the 47th Annual Sessions of Sri Langka Association for the Advancement of Science, 1991; Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1991; p. 92.

- Awmack, C.S.; Leather, S.R. Host plant quality and fecundity in herbivorous insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002, 47, 817–844.

- Klapwijk, M.J.; Björkman, C. Mixed forests to mitigate risk of insect outbreaks. Scand. J. For. Res. 2018, 33, 772–780.

- Schuler, L.J.; Bugmann, H.; Snell, R.S. From monocultures to mixed-species forests: Is tree diversity key for providing ecosystem services at the landscape scale? Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 32, 1499–1516.

- Jactel, H.; Brockerhoff, E.G. Tree diversity reduces herbivory by forest insects. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 835–848.

- Castagneyrol, B.; Jactel, H.; Vacher, C.; Brockerhoff, E.G.; Koricheva, J. Effects of plant phylogenetic diversity on herbivory depend on herbivore specialization. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 51, 134–141.

- Guyot, V.; Castagneyrol, B.; Vialatte, A.; Deconchat, M.; Jactel, H. Tree diversity reduces pest damage in mature forests across Europe. Biol. Lett. 2016, 12, 20151037.

- Kaitaniemi, P.; Riihimäki, J.; Koricheva, J.; Vehviläinen, H. Experimental evidence for associational resistance against the European pine sawfly in mixed tree stands. Silva Fennica 2007, 41, 259–268.

- Wetzel, W.; Kharouba, H.; Robinson, M.; Holyoak, M.; Karban, R. Variability in plant nutrients reduces insect herbivore performance. Nature 2016, 539, 425–427.

- Root, R.B. Organization of a plant-arthropod association in simple and diverse habitats: The fauna of Collards (Brassica Oleracea). Ecol. Monogr. 1972, 43, 95–120.

- Russel, E.P. Enemies Hypothesis: A review of the effect of vegetational diversity on predatory insects and parasitoids. Environ. Entomol. 1989, 18, 590–599.

- O’Rourke, M.E.; Petersen, M.J. Extending the ‘resource concentration hypothesis’ to the landscape-scale by considering dispersal mortality and fitness costs. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 249, 1–3.

- Stiling, P.; Rossi, A.M.; Cattell, M.V. Associational resistance mediated by natural enemies. Ecol. Entomol. 2003, 28, 587–593.

- Jactel, H.; Bauhus, J.; Boberg, J.; Bonal, D.; Castagneyrol, B.; Gardiner, B.; Gonzalez-Olabarria, J.R.; Koricheva, J.; Meurisse, N.; Brockerhoff, E.G. Tree diversity drives forest stand resistance to natural disturbances. Curr. For. Rep. 2017, 3, 223–243.

- Pamuji, R.; Rahardjo, B.T.; Tarno, H. Populasi dan serangan hama ulat kantung Metisa plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) serta parasitoidnya di perkebunan kelapa sawit Kabupaten Donggala, Sulawesi Tengah. J. HPT 2013, 1, 58–71.

- Fuat, S.; Adam, N.A.; Hazmi, I.R.; Yaakop, S. Interactions between Metisa plana, its hyperparasitoids and primary parasitoids from good agriculture practices (GAP) and non-gap oil palm plantations. Community Ecol. 2022.

- Badrulisham, A.S.; Bakar, M.A.L.A.; Md-Zain, B.M.; Md-Nor, S.; Abd Rahman, M.R.; Mohd-Yusof, N.S.; Halim, M.; Yaakop, S. Metabarcoding of parasitic wasp, Dolichogenidea metesae (Nixon) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) that parasitizing bagworm, Metisa plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2022, 33, 23–42.

More

Information

Subjects:

Entomology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.9K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

23 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No