| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alvaro Ignacio Vidal Valenzuela | + 4008 word(s) | 4008 | 2022-06-21 18:25:44 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | + 1 word(s) | 4009 | 2022-06-22 03:25:57 | | | | |

| 3 | Alvaro Ignacio Vidal Valenzuela | Meta information modification | 4009 | 2022-06-22 10:09:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) is one of the main fruit crops worldwide, with near of 7.3 million hectares planted in 2020, but along with its economic relevance, it has been associated with diverse pathogens that affect grapevine yield, fruit, and wine quality, of which powdery mildew is the most important disease prior to harvest. Its causal agent is the biotrophic fungus Erysiphe necator, which generates a decrease in cluster weight, delays fruit ripening, and reduces photosynthetic and transpiration rates. In addition, powdery mildew induces metabolic reprogramming in its host, affecting primary metabolism. Most commercial grapevine cultivars are highly susceptible to powdery mildew; consequently, large quantities of fungicide are applied during the productive season. These pesticide applications have been associated with high exposure to it, and pesticides are associated with health problems, negative environmental impacts, and high costs for farmers. In parallel, consumers are demanding more sustainable practices during food production. Therefore, new grapevine cultivars with genetic resistance to powdery mildew are needed for sustainable viticulture, while maintaining yield, fruit, and wine quality. Two main gene families confer resistance to powdery mildew in the Vitaceae, Run (Resistance to Uncinula necator) and Ren (Resistance to Erysiphe necator), and the resistance they confer is associated with the presence of each locus since there are still no genes that alone can produce a powerful genetic resistance. Because the resistance mediated by the plant immune response is highly complex and considers the evolution and adaptation of the pathogen in parallel to that of the plant.

1. Introduction

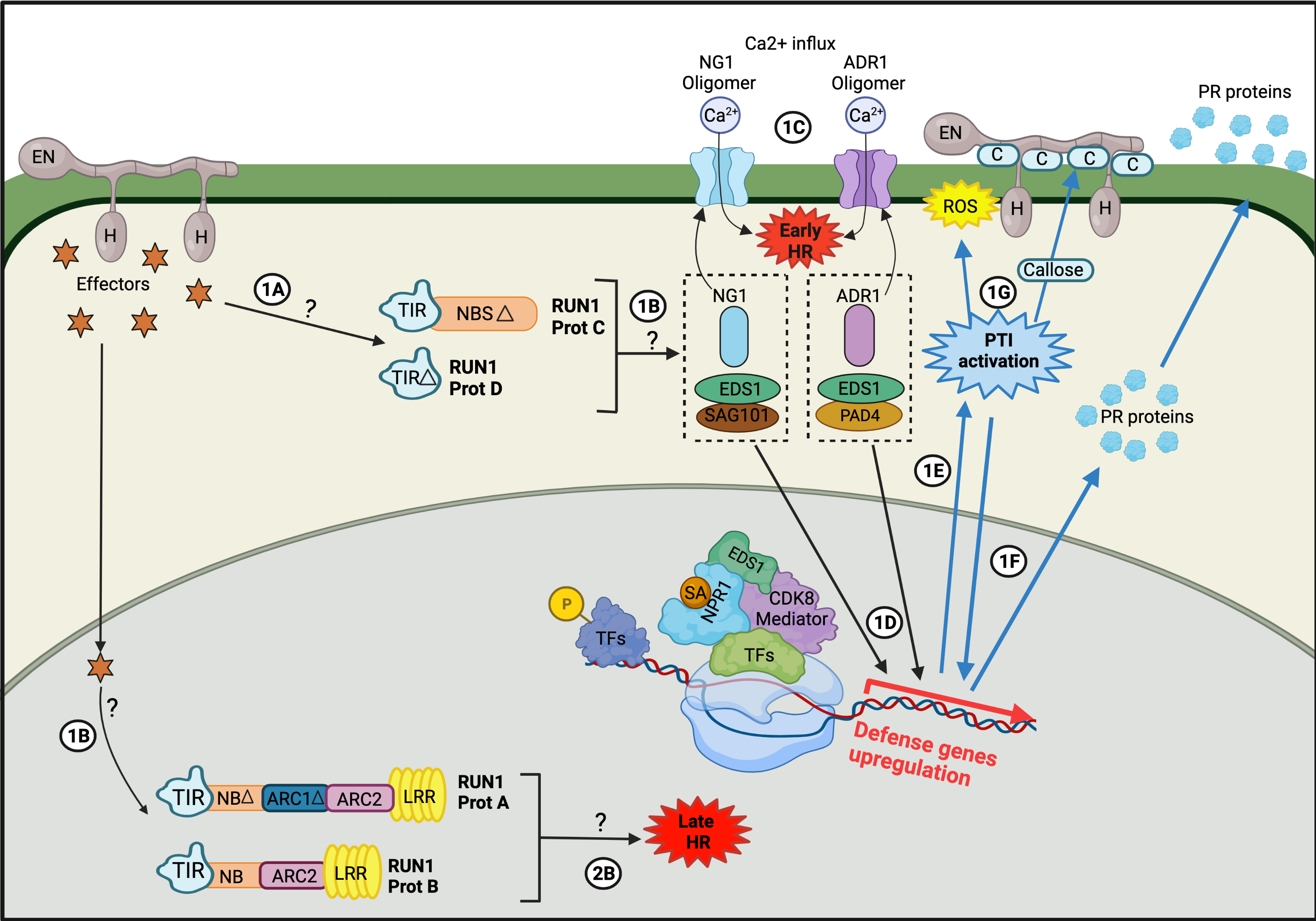

2. Host Response

3. Mapping Resistance Genes for Powdery Mildew Resistance Using Interspecific Crosses

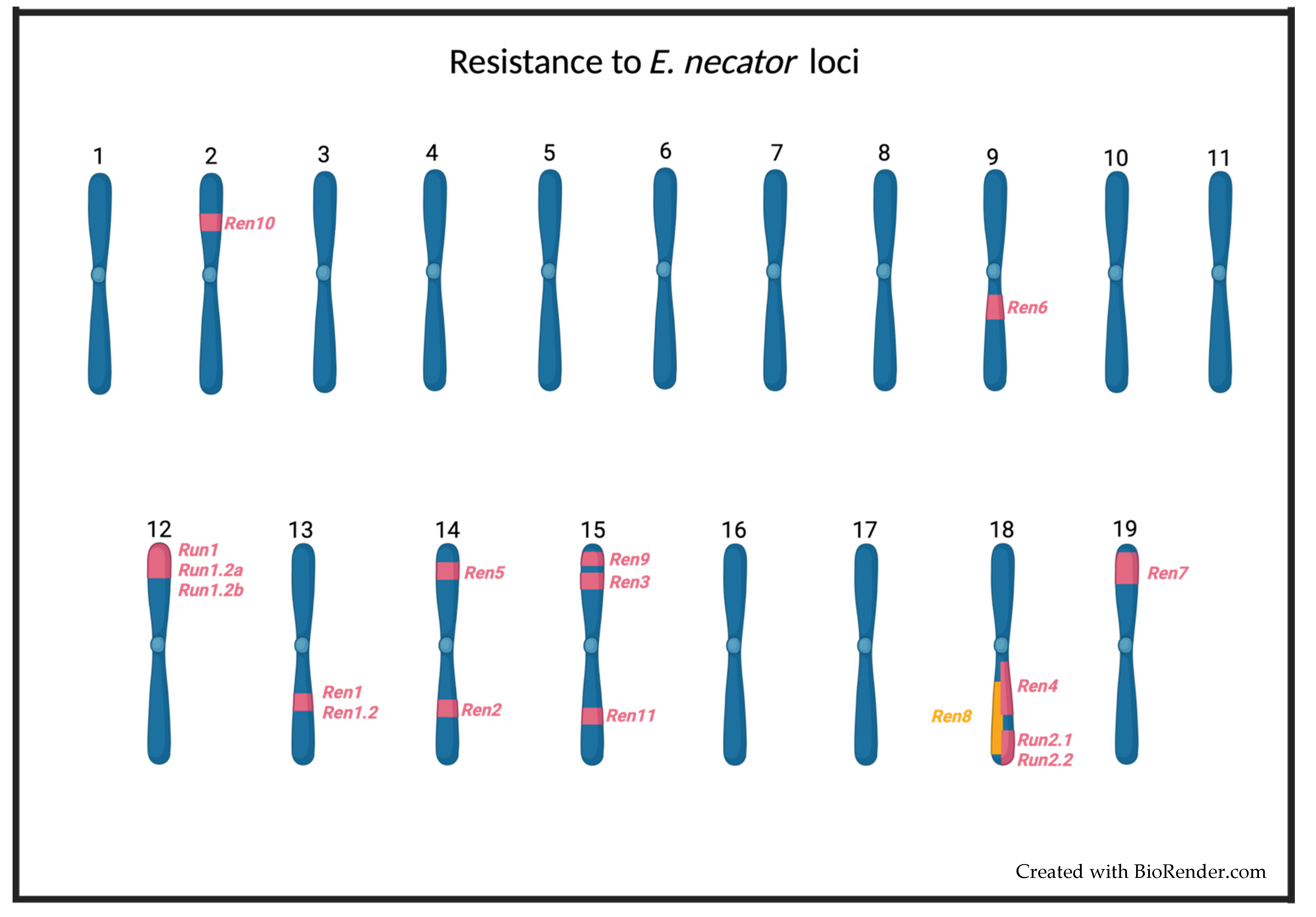

4. Run and Ren Resistance Loci

|

Locus |

Donor |

Host Response |

Resistance Level |

Reference |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PCD |

Callose |

ROS |

||||

|

Run1 |

M. rotundifolia G52 1 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Variable * |

|

|

Run1.2a |

M. rotundifolia1 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Variable * |

[71] |

|

Run1.2b |

M. rotundifolia1 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Variable * |

[71] |

|

Run2.1 |

M. rotundifolia ‘Magnolia’ 1 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial |

[55] |

|

Run2.2 |

M. rotundifolia ‘Trayshed’ 1 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial * |

[55] |

|

Ren1 |

V. vinifera cv. ‘Kismish vatkana’ 2 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Total |

[59] |

|

Ren1.2 |

V. vinifera cv. ‘Shavtsitka’ 3 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial |

[68] |

|

Ren2 |

V. cinerea2 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial |

|

|

Ren3 |

‘Regent’ 4 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Partial |

|

|

Ren4 |

V. romanetii2 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial |

[54] |

|

Ren5 |

M. rotundifolia ‘Regale’ 1 |

n.i. |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Total |

[60] |

|

Ren6 |

V. piasezki2 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Total |

[57] |

|

Ren7 |

V. piasezki2 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial |

[57] |

|

Ren8 |

Unknown 4 |

n.i. |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial |

[66] |

|

Ren9 |

‘Regent’ 4 |

Yes |

n.i. |

n.i. |

Partial |

|

|

Ren10 |

‘Seyval blanc’ 4 |

n.i. |

n.i |

n.i. |

Partial |

[67] |

|

Ren11 |

Vitis aestivalis2 |

n.i. |

n.i. |

n.i |

Partial |

[61] |

5. Locus Stacking: The Search for Durable and Broad-Spectrum Resistance

* Race-specific, as this effect was not seen with the Musc4 isolate.

6. Development of Genetic Resistance by Gene Editing

7. Final Remarks

We are experiencing a devastated climate change phenomenon, which among its most important effects for food production are drought, the increase of insects and the elevated spread of pathogenic fungi. This scenario is especially worrying in woody plants such as vitis, because the study of its genome becomes very complex, due to the long waiting times for transformations, the genetic differences between each cultivar, and the high susceptibility of this plant to biotic and abiotic stress. Therefore, it becomes very important for current scientists to work to ensure the presence of this genus for future generations, in areas from biotechnology for genetic modifications, to engineering to create specific irrigation systems. But above all, take advantage of the knowledge that we have generated as a scientific community, disperse it in the population, and be able to achieve regulatory changes that allow us to dream, without irrational fears, in genetic improvements that benefit everyone.

References

- OIV. 2019 Statistical Report on World Vitiviniculture. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/6782/oiv-2019-statistical-report-on-world-vitiviniculture.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- OIV. State of the World Viticultural Sector in 2020. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/7909/oiv-state-of-the-world-vitivinicultural-sector-in-2020.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Armijo, G.; Espinoza, C.; Loyola, R.; Restovic, F.; Santibáñez, C.; Schlechter, R.; Agurto, M.; Arce-Johnson, P. Grapevine biotechnology: Molecular approaches underlying abiotic and biotic stress responses. In Grape and Wine Biotechnology; Morata, A., Loira, I., Eds.; InTechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; pp. 3–42. ISBN 978-953-51-2692-8.

- Feechan, A.; Kabbara, S.; Dry, I.B. Mechanisms of powdery mildew resistance in the Vitaceae family. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 263–274.

- Dry, I.B.; Feechan, A.; Anderson, C.; Jermakow, A.M.; Bouquet, A.; Adam-Blondon, A.-F.; Thomas, M.R. Molecular strategies to enhance the genetic resistance of grapevines to powdery mildew. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2010, 16, 94–105.

- Pearson, R.C.; Gadoury, D.M. Grape powdery mildew. In Plant Diseases of International Importance; Kumar, J., Chaube, H.S., Singh, U.S., Mukhopadhyay, A.N., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1992; Volume III, pp. 129–146.

- Ferreira, R.B.; Monteiro, S.S.; Piçarra-Pereira, M.A.; Teixeira, A.R. Engineering grapevine for increased resistance to fungal pathogens without compromising wine stability. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 168–173.

- Pimentel, D.; Amaro, R.; Erban, A.; Mauri, N.; Soares, F.; Rego, C.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Mithöfer, A.; Kopka, J.; Fortes, A.M. Transcriptional, hormonal, and metabolic changes in susceptible grape berries under powdery mildew Infection. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6544–6569.

- Gaunt, R.E. The relationship between plant disease severity and yield. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 1995, 33, 119–144.

- Madden, L.V.; Nutter, F.W. Modeling crop losses at the field scale. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1995, 17, 124–137.

- Gadoury, D.M.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Wilcox, W.F.; Dry, I.B.; Seem, R.C.; Milgroom, M.G. Grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator): A fascinating system for the study of the biology, ecology and epidemiology of an obligate biotroph: Grapevine powdery mildew. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 1–16.

- Calonnec, A.; Cartolaro, P.; Poupot, C.; Dubourdieu, D.; Darriet, P. Effects of Uncinula necator on the yield and quality of grapes (Vitis vinifera) and Wine. Plant Pathol. 2004, 53, 434–445.

- Lopez Pinar, A.; Rauhut, D.; Ruehl, E.; Buettner, A. Quantification of the changes in potent wine odorants as Induced by bunch rot (Botrytis cinerea) and powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator). Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 57.

- Amati, A.; Piva, A.; Castellari, M. Preliminary studies on the effect of Oidium tuckeri on the phenolic composition of grapes and wines. Vitis 1996, 35, 149–150.

- Marsh, E.; Alvarez, S.; Hicks, L.M.; Barbazuk, W.B.; Qiu, W.; Kovacs, L.; Schachtman, D. Changes in protein abundance during powdery mildew infection of leaf tissues of Cabernet Sauvignon grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Proteomics 2010, 10, 2057–2064.

- Fung, R.W.M.; Gonzalo, M.; Fekete, C.; Kovacs, L.G.; He, Y.; Marsh, E.; McIntyre, L.M.; Schachtman, D.P.; Qiu, W. Powdery mildew induces defense-oriented reprogramming of the transcriptome in a susceptible but not in a resistant grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 236–249.

- Saddhe, A.A.; Manuka, R.; Penna, S. Plant Sugars: Homeostasis and transport under abiotic stress in plants. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 171, 739–755.

- Stermer, B.A.; Bianchini, G.M.; Korth, K.L. Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase activity in plants. J. Lip. Res. 1994, 35, 1133–1140.

- Gadoury, D.M.; Seem, R.C.; Ficke, A.; Wilcox, W.F. Ontogenic resistance to powdery mildew in grape berries. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 547–555.

- Belpoggi, F.; Soffritti, M.; Guarino, M.; Lambertini, L.; Cevolani, D.; Maltoni, C. Results of Long-Term Experimental Studies on the Carcinogenicity of Ethylene-Bis-Dithiocarbamate (Mancozeb) in Rats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 982, 123–136.

- Cecconi, S.; Paro, R.; Rossi, G.; Macchiarelli, G. The effects of the endocrine disruptors dithiocarbamates on the mammalian ovary with particular regard to mancozeb. CPD 2007, 13, 2989–3004.

- Calviello, G.; Piccioni, E.; Boninsegna, A.; Tedesco, B.; Maggiano, N.; Serini, S.; Wolf, F.I.; Palozza, P. DNA Damage and apoptosis induction by the pesticide mancozeb in rat cells: Involvement of the oxidative mechanism. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006, 211, 87–96.

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides: An update of human exposure and toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 549–599.

- Pandey, A.; Jaiswar, S.; Ansari, N.; Deo, S.; Sankhwar, P.; Pant, S.; Upadhyay, S. Pesticide risk and recurrent pregnancy loss in Females of subhumid region of India. Niger Med. J. 2020, 61, 55.

- Komárek, M.; Čadková, E.; Chrastný, V.; Bordas, F.; Bollinger, J.C. Contamination of vineyard Soils with fungicides: A review of environmental and toxicological aspects. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 138–151.

- Dumitriu, G.-D.; Teodosiu, C.; Cotea, V.V. Management of pesticides from vineyard to wines: Focus on wine safety and pesticides removal by emerging technologies. In Grapes and Wine; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–27.

- Peeters, A.; Lefebvre, O.; Balogh, L. A green deal for implementing agroecological systems: Reforming the common agricultural policy of the European Union. Landbauforsch. J. Sustain. Org. Agric. Syst. 2021, 70, 83–93.

- Borrello, M.; Cembalo, L.; Vecchio, R. Role of Information in consumers’ preferences for eco-sustainable genetic improvements in plant breeding. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255130.

- Abramovitch, R.B.; Anderson, J.C.; Martin, G.B. Bacterial elicitation and evasion of plant innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2006, 7, 601–611.

- Gao, Y.R.; Han, Y.-T.; Zhao, F.-L.; Li, Y.-J.; Cheng, Y.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wen, Y.-Q. Identification and utilization of a new Erysiphe necator isolate NAFU1 to quickly evaluate powdery mildew resistance in wild Chinese grapevine species using detached leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 98, 12–24.

- He, P.; Shan, L.; Lin, N.-C.; Martin, G.B.; Kemmerling, B.; Nürnberger, T.; Sheen, J. Specific bacterial suppressors of MAMP signaling upstream of MAPKKK in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Cell 2006, 125, 563–575.

- Li, M.Y.; Jiao, Y.T.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhang, N.; Wang, B.B.; Liu, R.Q.; Yin, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, G.T. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated VvPR4b editing decreases downy mildew resistance in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 149.

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329.

- Qiu, W.; Feechan, A.; Dry, I. Current understanding of grapevine defense mechanisms against the biotrophic fungus (Erysiphe necator), the causal agent of powdery mildew disease. Hortic. Res. 2015, 2, 15020.

- Agurto, M.; Schlechter, R.O.; Armijo, G.; Solano, E.; Serrano, C.; Contreras, R.A.; Zúñiga, G.E.; Arce-Johnson, P. RUN1 and REN1 pyramiding in grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv. Crimson Seedless) displays an improved defense response leading to enhanced resistance to powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 758.

- Dalla Costa, L.; Piazza, S.; Campa, M.; Flachowsky, H.; Hanke, M.-V.; Malnoy, M. Efficient heat-shock removal of the selectable marker gene in genetically modified grapevine. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016, 124, 471–481.

- Dalla Costa, L.; Piazza, S.; Pompili, V.; Salvagnin, U.; Cestaro, A.; Moffa, L.; Vittani, L.; Moser, C.; Malnoy, M. Strategies to produce T-DNA free CRISP red fruit trees via Agrobacterium tumefaciens stable gene transfer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20155.

- Malnoy, M.; Viola, R.; Jung, M.-H.; Koo, O.-J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.-S.; Velasco, R.; Nagamangala Kanchiswamy, C. DNA-free genetically edited grapevine and apple protoplast using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1904.

- Dai, R.; Ge, H.; Howard, S.; Qiu, W. Transcriptional expression of stilbene synthase genes are regulated developmentally and differentially in response to powdery mildew in Norton and Cabernet Sauvignon grapevine. Plant Sci. 2012, 197, 70–76.

- Olivares, F.; Loyola, R.; Olmedo, B.; Miccono, M.d.l.Á.; Aguirre, C.; Vergara, R.; Riquelme, D.; Madrid, G.; Plantat, P.; Mora, R.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 targeted editing of genes associated with fungal susceptibility in Vitis vinifera L. Cv. Thompson Seedless using Geminivirus-derived replicons. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 791030.

- Wildermut, M.C.; Dewdney, J.; Wu, G.; Ausubel, F.M. Isochorimate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 2001, 414, 562–565.

- Derksen, H.; Rampitsch, C.; Daayf, F. Signaling cross-talk in plant disease resistance. Plant Sci. 2013, 207, 79–87.

- Belhadj, A.; Saigne, C.; Telef, N.; Cluzet, S.; Bouscaut, J.; Corio-Costet, M.F.; Mérillon, J.-M. Methyl jasmonate induces defense responses in grapevine and triggers protection against Erysiphe necator. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9119–9125.

- Belhadj, A.; Telef, N.; Cluzet, S.; Bouscaut, J.; Corio-Costet, M.-F.; Mérillon, J.-M. Ethephon elicits protection against Erysiphe necator in grapevine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5781–5787.

- Jacobs, A.L.; Dry, I.B.; Robinson, S.P. Induction of different pathogenesis-related cDNAs in grapevine infected with powdery mildew and treated with ethephon. Plant Pathol. 1999, 48, 325–336.

- Jiao, C.; Sun, X.; Yan, X.; Xu, X.; Yan, Q.; Gao, M.; Fei, Z.; Wang, X. Grape transcriptome response to powdery mildew infection: Comparative transcriptome profiling of Chinese wild grapes provides insights into powdery mildew resistance. Phytopathology 2021, 111, 2041–2051.

- Weng, K.; Li, Z.-Q.; Liu, R.-Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Xu, Y. Transcriptome of Erysiphe necator-infected Vitis pseudoreticulata leaves provides insight into grapevine resistance to powdery mildew. Hortic. Res. 2014, 1, 14049.

- Petrovic, T.; Perera, D.; Cozzolino, D.; Kravchuk, O.; Zanker, T.; Bennett, J.; Scott, E.S. Feasibility of discriminating powdery mildew-affected grape berries at harvest using mid-infrared attenuated total reflection spectroscopy and fatty acid profiling: Objective measures for grape powdery mildew. Australian J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 415–425.

- Vezzulli, S.; Dolzani, C.; Nicolini, D.; Bettinelli, P.; Migliaro, D.; Gratl, V.; Stedile, T.; Zatelli, A.; Dallaserra, M.; Clementi, S.; et al. Marker-assisted breeding for downy mildew, powdery mildew and phylloxera resistance at FEM. BIO Web Conf. 2019, 13, 01002.

- Grattapaglia, D.; Sederoff, R. Genetic linkage maps of Eucalyptus grandis and Eucalyptus urophylla using a pseudo-testcross: Mapping strategy and RAPD markers. Genetics 1994, 137, 1121–1137.

- Maul, H. Vitis International Variety Catalogue 2021. Available online: www.vivc.de (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Barker, C.L.; Donald, T.; Pauquet, J.; Ratnaparkhe, M.B.; Bouquet, A.; Adam-Blondon, A.F.; Thomas, M.R.; Dry, I. Genetic and physical mapping of the grapevine powdery mildew resistance gene, Run1, using a bacterial artificial chromosome Library. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 111, 370–377.

- Feechan, A.; Anderson, C.; Torregrosa, L.; Jermakow, A.; Mestre, P.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Merdinoglu, D.; Walker, A.R.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Reisch, B.; et al. Genetic dissection of a TIR-NB-LRR locus from the wild North American grapevine species Muscadinia rotundifolia identifies paralogous genes conferring resistance to major fungal and oomycete pathogens in cultivated grapevine. Plant J. 2013, 76, 661–674.

- Ramming, D.W.; Gabler, F.; Smilanick, J.; Cadle-Davidson, M.; Barba, P.; Mahanil, S.; Cadle-Davidson, L. A single dominant locus, Ren4, confers rapid non-race-specific resistance to grapevine powdery mildew. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 502–508.

- Riaz, S.; Tenscher, A.C.; Ramming, D.W.; Walker, M.A. Using a limited mapping strategy to identify major QTLs for resistance to grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) and their use in marker-assisted breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 122, 1059–1073.

- Mahanil, S.; Ramming, D.; Cadle-Davidson, M.; Owens, C.; Garris, A.; Myles, S.; Cadle-Davidson, L. Development of marker sets useful in the early selection of Ren4 powdery mildew resistance and seedlessness for table and raisin grape breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 23–33.

- Pap, D.; Riaz, S.; Dry, I.B.; Jermakow, A.; Tenscher, A.C.; Cantu, D.; Oláh, R.; Walker, M.A. Identification of two novel powdery mildew resistance loci, Ren6 and Ren7, from the wild Chinese grape species Vitis piasezkii. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 170.

- Cadle-Davidson, L.E. A Perspective on Breeding and Implementing Durable Powdery Mildew Resistance. Acta Hortic. 2019, 541–548.

- Hoffmann, S.; Di Gaspero, G.; Kovács, L.; Howard, S.; Kiss, E.; Galbács, Z.; Testolin, R.; Kozma, P. Resistance to Erysiphe necator in the grapevine ‘Kishmish Vatkana’ is controlled by a single locus through restriction of hyphal growth. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008, 116, 427–438.

- Blanc, S.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Dumas, V.; Mestre, P.; Merdinoglu, D. A reference genetic map of Muscadinia rotundifolia and identification of Ren5, a new major locus for resistance to grapevine powdery mildew. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 1663–1675.

- Karn, A.; Zou, C.; Brooks, S.; Fresnedo-Ramírez, J.; Gabler, F.; Sun, Q.; Ramming, D.; Naegele, R.; Ledbetter, C.; Cadle-Davidson, L. Discovery of the REN11 locus From Vitis aestivalis for stable resistance to grapevine powdery mildew in a family segregating for several unstable and tissue-specific quantitative resistance loci. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 733899.

- Ramming, D.W.; Gabler, F.; Smilanick, J.L.; Margosan, D.A.; Cadle-Davidson, M.; Barba, P.; Mahanil, S.; Frenkel, O.; Milgroom, M.G.; Cadle-Davidson, L. Identification of race-specific resistance in North American Vitis Spp. limiting Erysiphe Necator hyphal growth. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 83–93.

- Dalbó, M.A.; Ye, G.N.; Weeden, N.F.; Wilcox, W.F.; Reisch, B.I. Marker-assisted selection for powdery mildew resistance in grapes. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2001, 126, 83–89.

- Zendler, D.; Töpfer, R.; Zyprian, E. Confirmation and fine mapping of the resistance locus Ren9 from the grapevine cultivar ‘Regent’. Plants 2020, 10, 24.

- Zendler, D.; Schneider, P.; Töpfer, R.; Zyprian, E. Fine mapping of Ren3 reveals two loci mediating hypersensitive response against Erysiphe necator in grapevine. Euphytica 2017, 213, 68.

- Zyprian, E.; Ochßner, I.; Schwander, F.; Šimon, S.; Hausmann, L.; Bonow-Rex, M.; Moreno-Sanz, P.; Grando, M.S.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Merdinoglu, D.; et al. Quantitative trait loci affecting pathogen resistance and ripening of grapevines. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2016, 291, 1573–1594.

- Teh, S.L.; Fresnedo-Ramírez, J.; Clark, M.D.; Gadoury, D.M.; Sun, Q.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Luby, J.J. Genetic dissection of powdery mildew resistance in interspecific half-sib grapevine families using SNP-based maps. Mol. Breeding 2017, 37, 1.

- Possamai, T.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Merdinoglu, D.; Migliaro, D.; De Mori, G.; Cipriani, G.; Velasco, R.; Testolin, R. Construction of a high-density genetic map and detection of a major QTL of resistance to powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator Sch.) in Caucasian grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 528.

- Feechan, A.; Kocsis, M.; Riaz, S.; Zhang, W.; Gadoury, D.M.; Walker, M.A.; Dry, I.B.; Reisch, B.; Cadle-Davidson, L. Strategies for RUN1 deployment using RUN2 and REN2 to manage grapevine powdery mildew informed by studies of race specificity. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 1104–1113.

- Welter, L.J.; Göktürk-Baydar, N.; Akkurt, M.; Maul, E.; Eibach, R.; Töpfer, R.; Zyprian, E.M. Genetic mapping and localization of quantitative trait loci affecting fungal disease resistance and leaf morphology in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L). Mol. Breeding 2007, 20, 359–374.

- Massonnet, M.; Vondras, A.M.; Cochetel, N.; Riaz, S.; Pap, D.; Minio, A.; Figueroa-Balderas, R.; Walker, M.A.; Cantu, D. Characterization of the grape powdery mildew genetic resistance loci in Muscadinia rotundifolia Trayshed. bioRxiv 2021.

- Yahiaoui, N.; Srichumpa, P.; Dudler, R.; Keller, B. Genome analysis at different ploidy levels allows cloning of the powdery mildew resistance gene Pm3b from hexaploid wheat. Plant J. 2004, 37, 528–538.

- Cao, A.; Xing, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Qian, C.; Ni, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Serine/threonine kinase gene stpk-V, a key member of powdery mildew resistance gene Pm21, confes powdery mildew resistance in wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7727–7732.

- Hurni, S.; Brunner, S.; Buchmann, G.; Herren, G.; Jordan, T.; Krukowski, P.; Wicker, T.; Yahiaoui, N.; Mago, R.; Keller, B. Rye Pm8 and wheat Pm3 are orthologous genes and show evolutionary conservation of resistance function against powdery mildew. Plant J. 2013, 76, 957–969.

- He, H.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Ji, Y.; Ji, J.; Qiu, D.; Li, H.; Bie, T. Pm21, encoding a typical CC-NBS-LRR protein, confers broad-spectrum resistance to wheat powdery mildew disease. Mol Plant. 2018, 11, 879–882.

- Zou, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.W.; Kong, Z.S.; Tang, D.S. The NB-LRR gene Pm60 confers powdery mildew resistance in wheat. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 298–309.

- Golzar, H.; Shankar, M.; D´Antuono, M. Responses of commercial wheat varieties and differential lines to western Australian powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis f. Sp. Tritici) populations. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2016, 45, 347–355.

- Xu, Q.; Wen, X.; Deng, X. Isolation of TIR and NonTIR NBS–LRR resistance gene analogues and identification of molecular markers linked to a powdery mildew resistance locus in Chestnut Rose (Rosa roxburghii Tratt). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 111, 819–830.

- Thind, A.K.; Wicker, T.; Šimková, H.; Fossati, D.; Moullet, O.; Brabant, C.; Vrána, J.; Doležel, J.; Krattinger, S.G. Rapid cloning of genes in hexaploid wheat using cultivar-specific long-race chromosome assembly. Nat Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 793–796.

- Bouquet, A. Introduction Dans l’espèce Vitis vinifera L. d’un Caractère de Résistance à l’oidium (Uncinula necator Schw. Burr.) Issu de l’espèce Muscadinia rotundifolia (Michx.) Small. Vignevini 1986, 12, 141–146.

- Pauquet, J.; Bouquet, A.; This, P.; Adam-Blondon, A.F. Establishment of a local map of AFLP markers around the powdery mildew resistance gene Run1 in grapevine and assessment of their usefulness for marker assisted selection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 103, 1201–1210.

- Donald, T.M.; Pellerone, F.; Adam-Blondon, A.F.; Bouquet, A.; Thomas, M.R.; Dry, I.B. Identification of resistance gene analogs linked to a powdery mildew resistance locus in grapevine. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 610–618.

- Merdinoglu, D.; Schneider, C.; Prado, E.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Mestre, P. Breeding for durable resistance to downy and powdery mildew in grapevine. OENO One 2018, 52, 203–209.

- Anderson, C.; Choisne, N.; Adam-Blondon, A.-F.; Dry, I. Positional Cloning of Disease Resistance Genes in Grapevine. In Genetics, Genomics, and Breeding of Grapes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 214–238. ISBN 978-0-429-18941-8.

- Cadle-Davidson, L.; Mahanil, S.; Gadoury, D.M.; Kozma, P.; Reisch, B.I. Natural infection of Run1-positive vines by naïve genotypes of Erysiphe necator. Vitis 2011, 50, 85, 173–175.

- Mundt, C.C. Pyramiding for resistance durability: Theory and practice. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 792–802.

- McDonald, B.A.; Linde, C. Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2002, 40, 349–379.

- Meyer, D.; Pajonk, S.; Micali, C.; O’Connell, R.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Extracellular transport and integration of plant secretory proteins into pathogen-induced cell wall compartments. Plant J. 2009, 57, 986–999.

- Peressotti, E.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Delmotte, F.; Bellin, D.; Di Gaspero, G.; Testolin, R.; Merdinoglu, D.; Mestre, P. Breakdown of resistance to grapevine downy mildew upon limited deployment of a resistant variety. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 147.

- Wan, D.-Y.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.-Q. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of VvMLO3 results in enhanced resistance to powdery mildew in grapevine (Vitis vinifera). Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 116.