| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jaco Bakker | -- | 2328 | 2022-06-21 11:01:35 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -13 word(s) | 2315 | 2022-06-22 04:40:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

A herniation is a condition in which there is a protrusion of an organ, fascia, fat, or omentum through the wall of the cavity in which it is contained. A hernia may be classified into different categories based on the cause, location, size, recurrence, reducibility, contents, and symptoms. Inguinal hernia is described as a bulge of the peritoneum through a defect (congenital or acquired) in the muscular and fascial structures of the abdominal wall; a defect in the myofascial plane of the oblique and transversalis muscles and fascia. Inguinal hernias are classified into (1) indirect hernia, (2) direct hernia, (3) scrotal or giant hernia, (4) femoral hernia, and (5) others, i.e., rare hernias such as Spigelian hernias. Inguinal hernias are relatively common in both humans and domestic animal species, and surgery to repair an inguinal hernia is a nonurgent, routine procedure. However, every hernia carries a hazard of incarceration and strangulation, warranting immediate surgical treatment.

1. Epidemiology and Anamnesis

-

Trauma [11]. Although the exact role of trauma in the occurrence and progress of inguinal hernia remains unclear, accidents such as a fall from height while hopping from one tree to another may play a role;

-

Congenital weakness of muscles of the groin region or other congenital anomalies from the time of birth [11];

-

In utero lead exposure [12].

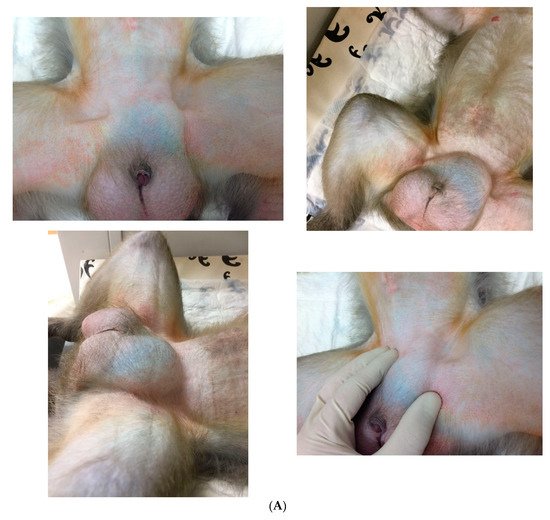

2. Clinical Signs

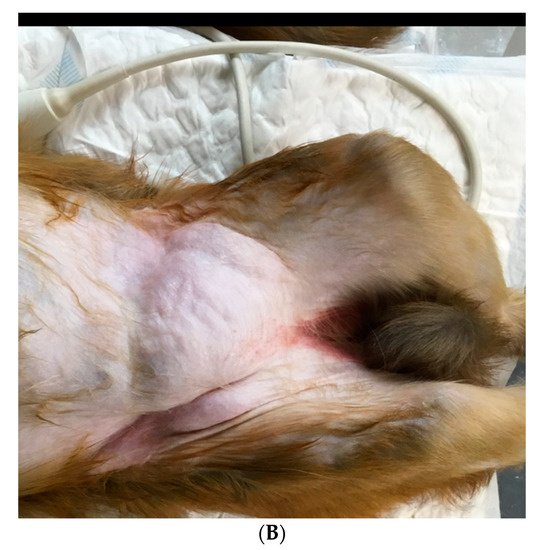

3. Diagnostics

4. Differential Diagnosis

5. Medical Management

References

- Öberg, S.; Andresen, K.; Rosenberg, J. Etiology of Inguinal Hernias: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Surg. 2017, 4, 52.

- Köckerling, F.; Simons, M.P. Current Concepts of Inguinal Hernia Repair. Visc. Med. 2018, 34, 145–150.

- Primatesta, P.; Goldacre, M.J. Inguinal hernia repair: Incidence of elective and emergency surgery, readmission and mortality. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 25, 835–839.

- Burcharth, J.; Pommergaard, H.C.; Rosenberg, J. The inheritance of groin hernia: A systematic review. Hernia 2013, 17, 183–189.

- Zoller, B.; Ji, J.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Shared and nonshared familial susceptibility to surgically treated inguinal hernia, femoral hernia, incisional hernia, epigastric hernia, and umbilical hernia. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 217, 289–299.

- Andrews, E.; Bissell, A. Comparative Studies of Hernia in Man and Animals. J. Urol. 1934, 31, 839–866.

- Cline, M.J.; Brignolo, L.; Ford, E.W. Chapter 10: Urogenital System. In Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research, Volume II: Diseases, 2nd ed.; Abee, C.R., Mansfield, K., Tardif, S., Morris, T., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012.

- Valverde, C.R.; Christe, K.L. Chapter 22: Radiographic imaging of nonhuman primates. In The Laboratory Primate; Wolfe-Coote, S., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2005.

- Butler, T.M.; Brown, B.G.; Dysko, R.C.; Ford, E.W.; Hoskins, D.E.; Klein, H.J.; Levin, J.L.; Murray, K.A.; Rosenberg, D.P.; Southers, J.L.; et al. Chapter 13: Medical management. In Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Biology and Management; Bennett, T.B., Abee, C.R., Henrickson, R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995.

- Fowler, M.E. Chapter 37: New world and old world monkeys, In Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine; Miller, R.E., Fowler, M.E., Eds.; Saunders: St. Louis, Mo, USA, 2014; Volume 8, p. 307.

- Kumar, V.; Raj, A. Surgical management of unilateral inguinoscrotal hernia in a male rhesus macaque. J. Vet. Sci. Technol. 2012, 1, 1–4.

- Krugner-Higby, L.; Rosenstein, A.; Handschke, L.; Luck, M.; Laughlin, N.K.; Mahvi, D.; Gendron, A. Inguinal hernias, endometriosis, and other adverse outcomes in rhesus monkeys following lead exposure. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2003, 25, 561–570.

- Berg, M.R.; MacAllister, R.P.; Martin, L.D. Nonreducible Inguinal Hernia Containing the Uterus and Bilateral Adnexa in a Rhesus Macaque (Macaca mulatta). Comp. Med. 2017, 67, 537–540.

- Bush, M.; Heller, R.; Gray, C.W.; Oh, K.S.; James, A.E. Peritoneography and Herniography in Non-Human Primates. Vet. Radiol. 1975, 15, 77–82.

- Grosfeld, J.L. Current concepts in inguinal hernia in infants and children. World J. Surg. 1989, 13, 506–515.

- Liem, M.S.; van der Graaf, Y.; Zwart, R.C.; Geurts, I.; van Vroonhoven, T.J. Risk factors for inguinal hernia in women: A case control study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 146, 721–726.

- Pastorino, A.; Alshuqayfi, A.A. Strangulated Hernia. In StatPearls ; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, January 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555972/ (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Sadoughi, B.; Dirheimer, M.; Regnard, P.; Wanert, F. Surgical management of a strangulated inguinal hernia in a Cynomolgus Monkey (Macaca fascicularis): A case report with discussion of diagnosis, and review of literature. Rev. De Primatol. 2019, 9, 1–11.

- Shakil, A.; Aparicio, K.; Barta, E.; Munez, K. Inguinal Hernias: Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 487–492.

- Miller, J.; Cho, J.; Michael, M.J.; Saouaf, R.; Towfigh, S. Role of imaging in the diagnosis of occult hernias. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 1077–1080.

- Robinson, A.; Light, D.; Kasim, A.; Nice, C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of radiology in the diagnosis of occult inguinal hernia. Surg. Endosc. 2013, 27, 11–18.

- James, A.E., Jr.; Heller, R.M., Jr.; Bush, M.; Gray, C.W.; Oh, K.S. Positive contrast peritoneography and herniography in primate animals. With special reference to indirect inguinal hernias. J. Med. Primatol. 1975, 4, 114–119.

- Kingsnorth, A.; LeBlanc, K. Hernias: Inguinal and incisional. Lancet 2003, 362, 1561–1571.

- Montgomery, J.; Dimick, J.B.; Telem, D.A. Management of Groin Hernias in Adults-2018. JAMA 2018, 320, 1029–1030.

- Srisajjakul, S.; Prapaisilp, P.; Bangchokdee, S. Comprehensive review of acute small bowel ischemia: CT imaging findings, pearls, and pitfalls. Emerg. Radiol. 2022, 29, 531–544.

- Gandhi, J.; Zaidi, S.; Suh, Y.; Joshi, G.; Smith, N.L.; Ali Khan, S. An index of inguinal and inguinofemoral masses in women: Critical considerations for diagnosis. Transl. Res. Anat. 2018, 12, 1–10.

- LeBlanc, K.E.; LeBlanc, L.L.; LeBlanc, K.A. Inguinal hernias: Diagnosis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 2013, 87, 844–848.

- Holzheimer, R.G. Inguinal Hernia: Classification, diagnosis and treatment--classic, traumatic and Sportsman’s hernia. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2005, 10, 121–134.

- Kouhia, S. Complication and Cost Analysis of Inguinal Hernia Surgery: Comparison of Open and Laparoscopic Techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Health Sciences Publications of the University of Eastern Finland, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland, 2016.

- HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 2018, 22, 1–165.

- Hammoud, M.; Gerken, J. Inguinal Hernia. In StatPearls ; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513332/ (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Kulacoglu, H. Current options in inguinal hernia repair in adult patients. Hippokratia 2011, 15, 223–231.

- van den Heuvel, B.; Dwars, B.J.; Klassen, D.R.; Bonjer, H.J. Is surgical repair of an asymptomatic groin hernia appropriate? A review. Hernia 2011, 15, 251–259.

- Fitzgibbons, R.J., Jr.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Gibbs, J.O.; Dunlop, D.D.; Reda, D.J.; McCarthy, M., Jr.; Neumayer, L.A.; Barkun, J.S.; Hoehn, J.L.; Murphy, J.T.; et al. Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 285–292.

- Gallegos, N.C.; Dawson, J.; Jarvis, M.; Hobsley, M. Risk of strangulation in groin hernias. Br. J. Surg. 1991, 178, 1171–1173.

- McFadyen, B.V.; Mathis, C.R. Inguinal herniorraphy: Complications and recurrences. Semin. Laparosc. Surg. 1994, 1, 128–140.

- Bali, C.; Tsironis, A.; Zikos, N.; Mouselimi, M.; Katsamakis, N. An unusual case of a strangulated right inguinal hernia containing the sigmoid colon. Int. J. Surg. Case. Rep. 2011, 2, 53–55.

- Bax, T.; Sheppard, B.C.; Crass, R.A. Surgical options in the management of groin hernias. Am, Fam, Physician 1999, 59, 893–906.

- Itani, K.M.F.; Fitzgibbons, R. Approach to Groin Hernias. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 551–552.

- Kokotovic, D.; Bisgaard, T.; Helgstrand, F. Long-term Recurrence and Complications Associated With Elective Incisional Hernia Repair. JAMA 2016, 316, 1575–1582.

- Brown, C.N.; Finch, J.G. Which mesh for hernia repair? Ann. R Coll. Surg. Engl. 2010, 92, 272–278.

- Kempton, S.J.; Israel, J.S.; Capuano, S., III; Poore, S.O. Repair of a Large Ventral Hernia in a Rhesus Macaque (Macaca mulatta) by Using an Abdominal Component Separation Technique. Comp. Med. 2018, 68, 177–181.

- Gudigopuram, S.V.R.; Raguthu, C.C.; Gajjela, H.; Kela, I.; Kakarala, C.L.; Hassan, M.; Belavadi, R.; Sange, I. Inguinal Hernia Mesh Repair: The Factors to Consider When Deciding Between Open Versus Laparoscopic Repair. Cureus 2021, 13, e19628.

- Crawford, D.L.; Phillips, E.H. Laparoscopic repair and groin hernia surgery. Surg. Clin. North Am. 1998, 78, 1047–1062.

- Tamme, C.; Scheidbach, H.; Hampe, C.; Schneider, C.; Köckerling, F. Totally extraperitoneal endoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TEP). Surg. Endosc. 2003, 17, 190–195.

- Fossum, T.W. Chapter 6: Preparation of the operative site. In Small Animal Surgery, 2nd ed.; Fossum, T.W., Hedlund, C.S., Hulse, D.A., Johnson, A.L., Seim, H.B., Willard, M.D., Carroll, G.L., Eds.; Mosby Inc.: St. Louis, Mo, USA, 2002.

- Fossum, T.W. Chapter 20 Surgery of the abdominal cavity. In Small Animal Surgery, 2nd ed.; Fossum, T.W., Hedlund, C.S., Hulse, D.A., Johnson, A.L., Seim, H.B., Willard, M.D., Carroll, G.L., Eds.; Mosby Inc.: St. Louis, Mo, USA, 2002.

- Popilskis, S.J.; Kohn, D.F. Chapter 11: Anesthesia and Analgesia in Nonhuman Primates. In Anesthesia and Analgesia in Laboratory Animals; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 233–255.

- Pizarro, A.I.; Amarasekaran, B.; Brown, D.; Pizzi, R. Laparoscopic repair of an umbilical hernia in a Western chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) rescued in Sierra Leone. J. Med. Primatol. 2019, 48, 189–191.

- Jenkins, J.T.; O’Dwyer, P.J. Inguinal hernias. Br. Med. J. 2008, 336, 269–272.

- Mallick, I.H.; Yang, W.; Winslet, M.C.; Seifalian, A.M. Ischemia-reperfusion injury of the intestine and protective strategies against injury. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2004, 49, 1359–1377.

- Khalil, A.A.; Aziz, F.A.; Hall, J.C. Reperfusion Injury. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 117, 1024–1033.

- Smeak, D.D.; Monnet, E. Chapter 25: Enterectomy. In Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals; Monnet, E., Smeak, D.D., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 187–202.

- Bala, M.; Kashuk, J.; Moore, E.E.; Kluger, Y.; Biffl, W.; Augusto Gomes, C.; Ben-Ishay, O.; Rubinstein, C.; Balogh, J.Z.; Civil, I.; et al. Acute mesenteric ischemia: Guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2017, 12, 1–11.