Video Upload Options

The cytosolic PNGase (peptide:N-glycanase), also known as peptide-N4-(N-acetyl-β-glucosaminyl)-asparagine amidase, is a well-conserved deglycosylation enzyme (EC 3.5.1.52) which catalyzes the non-lysosomal hydrolysis of an N(4)-(acetyl-β-d-glucosaminyl) asparagine residue (Asn, N) into a N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminyl-amine and a peptide containing an aspartate residue (Asp, D). This enzyme (NGLY1) plays an essential role in the clearance of misfolded or unassembled glycoproteins through a process named ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Accumulating evidence also points out that NGLY1 deficiency can cause an autosomal recessive (AR) human genetic disorder associated with abnormal development and congenital disorder of deglycosylation.

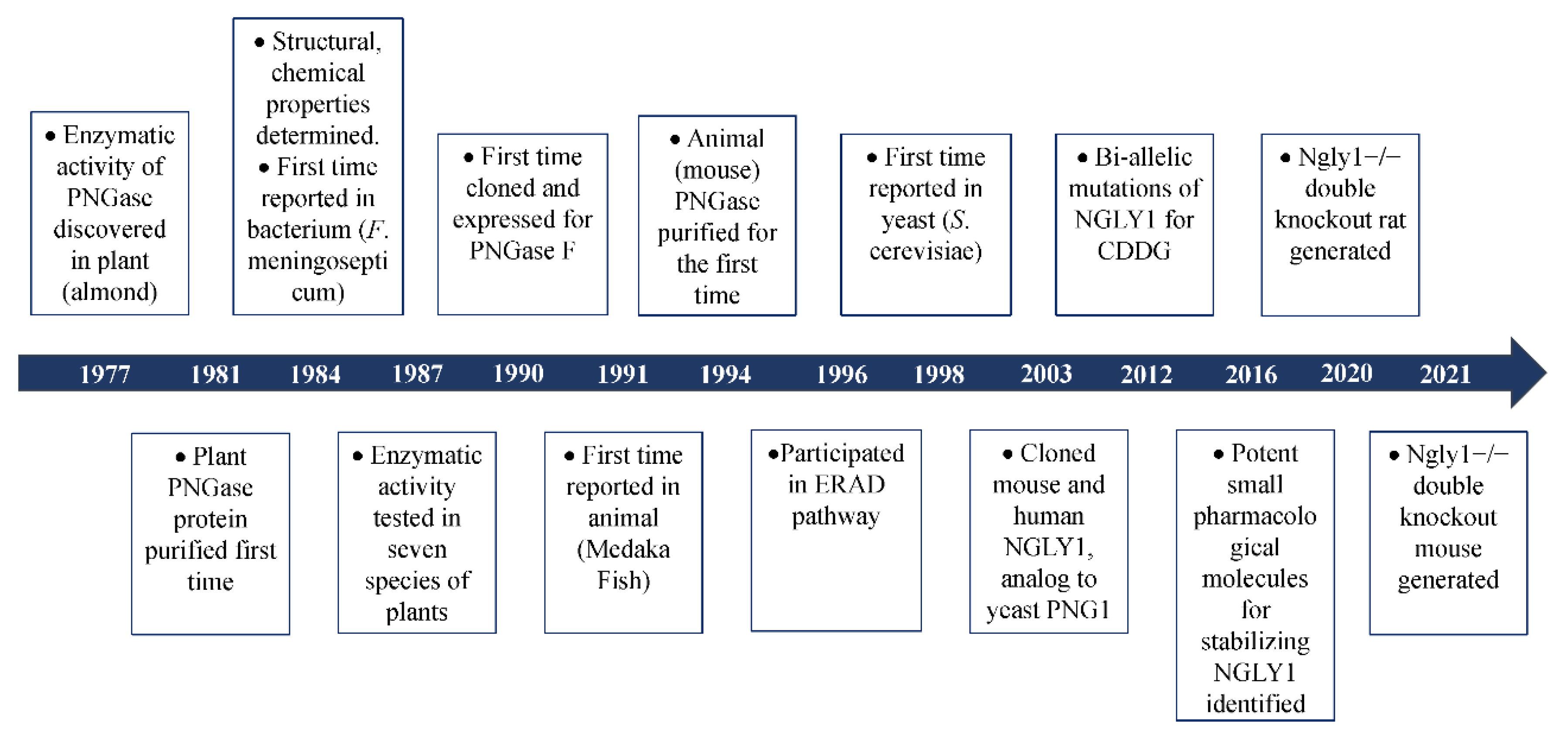

1. The Discovery of Peptide:N-Glycanase

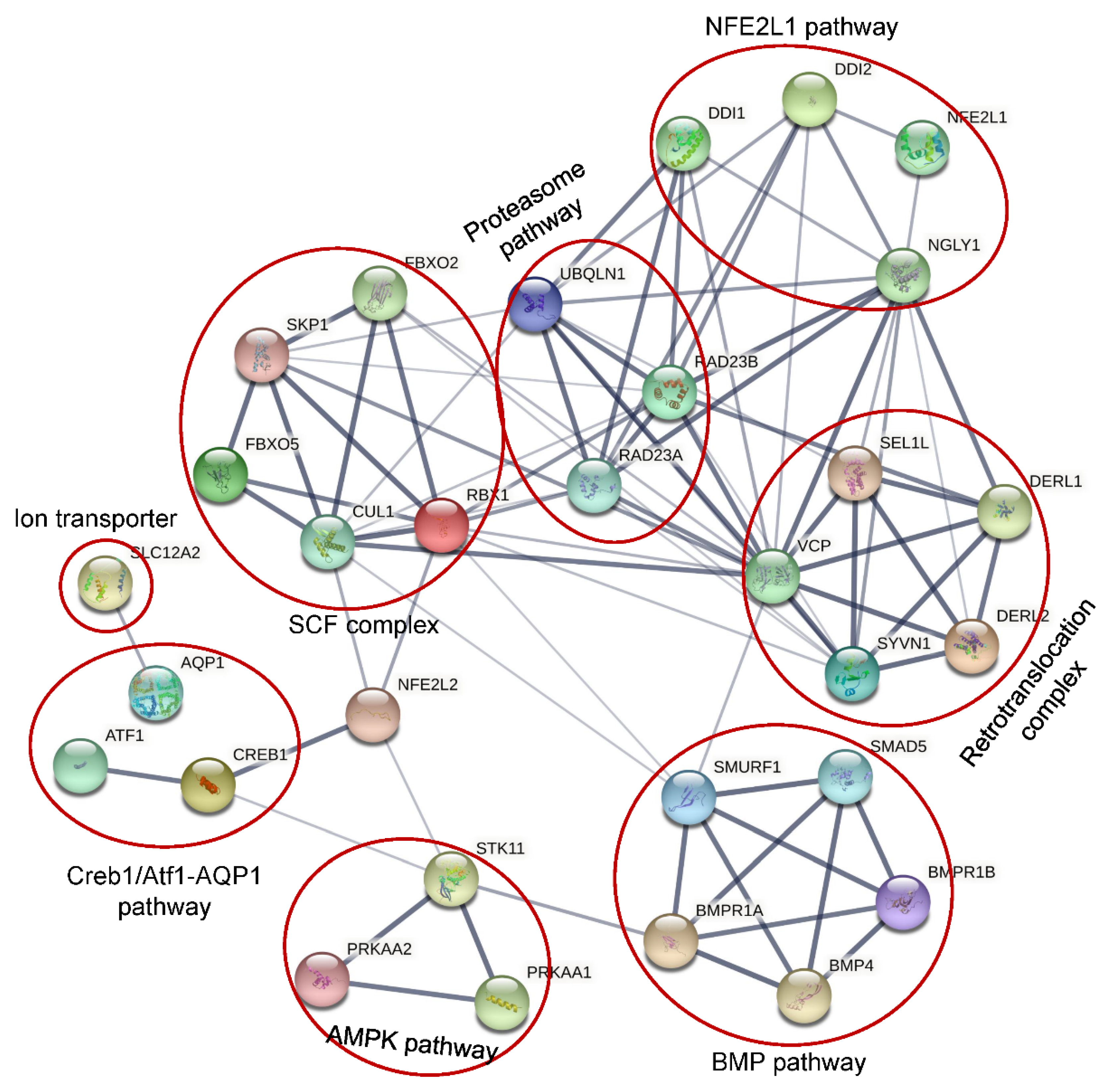

2. Different Functional Pathways Participated in by NGLY1

2. 1. NFE2L1 Pathway

2.2. Creb1/Atf1-AQP Pathway

2.3. BMP Pathway

2.4. AMPK Pathway

2.5. SLC12A2

3. Potential Treatments for NGLY1-CDDG

3.1. Exogenous Restoration of NGLY1 Expression

3.2. Targeting ENGase with Small Inhibitors

3.3. Inhibition FOXB6 (Fbs2)

3.4. Activation of NFE2L2

References

- Takahashi, N. Demonstration of a new amidase acting on glycopeptides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1977, 76, 1194–1201.

- Sugiyama, K.; Ishihara, H.; Tejima, S.; Takahashi, N. Demonstration of a new glycopeptidase, from jack-bean meal, acting on aspartylglucosylamine linkages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983, 112, 155–160.

- Plummer, T.H., Jr.; Phelan, A.W.; Tarentino, A.L. Detection and quantification of peptide-N4-(N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminyl)asparagine amidases. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987, 163, 167–173.

- Diepold, A.; Li, G.; Lennarz, W.J.; Nurnberger, T.; Brunner, F. The Arabidopsis AtPNG1 gene encodes a peptide:N-glycanase. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007, 52, 94–104.

- Takahashi, N.; Nishibe, H. Some characteristics of a new glycopeptidase acting on aspartylglycosylamine linkages. J. Biochem. 1978, 84, 1467–1473.

- Plummer, T.H., Jr.; Tarentino, A.L. Facile cleavage of complex oligosaccharides from glycopeptides by almond emulsin peptide:N-glycosidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 10243–10246.

- Nishibe, H.; Takahashi, N. The release of carbohydrate moieties from human fibrinogen by almond glycopeptidase without alteration in fibrinogen clottability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1981, 661, 274–279.

- Tarentino, A.L.; Plummer, T.H., Jr. Oligosaccharide accessibility to peptide:N-glycosidase as promoted by protein-unfolding reagents. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 10776–10780.

- Plummer, T.H., Jr.; Elder, J.H.; Alexander, S.; Phelan, A.W.; Tarentino, A.L. Demonstration of peptide:N-glycosidase F activity in endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase F preparations. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 10700–10704.

- Ishii, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Inoue, S.; Kenny, P.T.; Komura, H.; Inoue, Y. Free sialooligosaccharides found in the unfertilized eggs of a freshwater trout, Plecoglossus altivelis. A large storage pool of complex-type bi-, tri-, and tetraantennary sialooligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 1623–1630.

- Seko, A.; Kitajima, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Inoue, S.; Inoue, Y. Structural studies of fertilization-associated carbohydrate-rich glycoproteins (hyosophorin) isolated from the fertilized and unfertilized eggs of flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Presence of a novel penta-antennary N-linked glycan chain in the tandem repeating glycopeptide unit of hyosophorin. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 15922–15929.

- Seko, A.; Kitajima, K.; Inoue, Y.; Inoue, S. Peptide:N-glycosidase activity found in the early embryos of Oryzias latipes (Medaka fish). The first demonstration of the occurrence of peptide:N-glycosidase in animal cells and its implication for the presence of a de-N-glycosylation system in living organisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 22110–22114.

- Suzuki, T.; Seko, A.; Kitajima, K.; Inoue, Y.; Inoue, S. Identification of peptide:N-glycanase activity in mammalian-derived cultured cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 194, 1124–1130.

- Ftouhi-Paquin, N.; Hauer, C.R.; Stack, R.F.; Tarentino, A.L.; Plummer, T.H., Jr. Molecular cloning, primary structure, and properties of a new glycoamidase from the fungus Aspergillus tubigensis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 22960–22965.

- Suzuki, T.; Park, H.; Kitajima, K.; Lennarz, W.J. Peptides glycosylated in the endoplasmic reticulum of yeast are subsequently deglycosylated by a soluble peptide:N-glycanase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 21526–21530.

- Need, A.C.; Shashi, V.; Hitomi, Y.; Schoch, K.; Shianna, K.V.; McDonald, M.T.; Meisler, M.H.; Goldstein, D.B. Clinical application of exome sequencing in undiagnosed genetic conditions. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 353–361.

- Enns, G.M.; Shashi, V.; Bainbridge, M.; Gambello, M.J.; Zahir, F.R.; Bast, T.; Crimian, R.; Schoch, K.; Platt, J.; Cox, R.; et al. Mutations in NGLY1 cause an inherited disorder of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. Genet. Med. 2014, 16, 751–758.

- Lam, C.; Ferreira, C.; Krasnewich, D.; Toro, C.; Latham, L.; Zein, W.M.; Lehky, T.; Brewer, C.; Baker, E.H.; Thurm, A.; et al. Prospective phenotyping of NGLY1-CDDG, the first congenital disorder of deglycosylation. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 160–168.

- Haijes, H.A.; de Sain-van der Velden, M.G.M.; Prinsen, H.; Willems, A.P.; van der Ham, M.; Gerrits, J.; Couse, M.H.; Friedman, J.M.; van Karnebeek, C.D.M.; Selby, K.A.; et al. Aspartylglycosamine is a biomarker for NGLY1-CDDG, a congenital disorder of deglycosylation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 127, 368–372.

- Panneman, D.M.; Wortmann, S.B.; Haaxma, C.A.; van Hasselt, P.M.; Wolf, N.I.; Hendriks, Y.; Kusters, B.; van Emst-de Vries, S.; van de Westerlo, E.; Koopman, W.J.H.; et al. Variants in NGLY1 lead to intellectual disability, myoclonus epilepsy, sensorimotor axonal polyneuropathy and mitochondrial dysfunction. Clin. Genet. 2020, 97, 556–566.

- Hwang, J.; Qi, L. Quality Control in the Endoplasmic Reticulum: Crosstalk between ERAD and UPR pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 593–605.

- Hartl, F.U. Protein Misfolding Diseases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 21–26.

- Karousis, E.; Mühlemann, O. Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay Begins Where Translation Ends. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 11, a032862.

- Sovolyova, N.; Healy, S.; Samali, A.; Logue, S.E. Stressed to death—Mechanisms of ER stress-induced cell death. Biol. Chem. 2013, 395, 1–13.

- Kario, E.; Tirosh, B.; Ploegh, H.L.; Navon, A. N-Linked Glycosylation Does Not Impair Proteasomal Degradation but Affects Class I Major Histocompatibility Complex Presentation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 244–254.

- Blom, D.; Hirsch, C.; Stern, P.; Tortorella, M.; Ploegh, H.L. A glycosylated type I membrane protein becomes cytosolic when peptide:N-glycanase is compromised. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 650–658.

- Owings, K.G.; Lowry, J.B.; Bi, Y.; Might, M.; Chow, C.Y. Transcriptome and functional analysis in a Drosophila model of NGLY1 deficiency provides insight into therapeutic approaches. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 1055–1066.

- Asahina, M.; Fujinawa, R.; Nakamura, S.; Yokoyama, K.; Tozawa, R.; Suzuki, T. Ngly1−/− rats develop neurodegenerative phenotypes and pathological abnormalities in their peripheral and central nervous systems. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, 1635–1647.

- Tambe, M.A.; Ng, B.G.; Freeze, H.H. N-Glycanase 1 Transcriptionally Regulates Aquaporins Independent of Its Enzymatic Activity. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 4620–4631.e4.

- Suzuki, T.; Park, H.; Hollingsworth, N.M.; Sternglanz, R.; Lennarz, W.J. PNG1, a Yeast Gene Encoding a Highly Conserved Peptide:N-Glycanase. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 149, 1039–1052.

- Mueller, W.F.; Jakob, P.; Sun, H.; Clauder-Münster, S.; Ghidelli-Disse, S.; Ordonez, D.; Boesche, M.; Bantscheff, M.; Collier, P.; Haase, B.; et al. Loss of N-Glycanase 1 Alters Transcriptional and Translational Regulation in K562 Cell Lines. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020, 10, 1585–1597.

- Misaghi, S.; Pacold, M.E.; Blom, D.; Ploegh, H.L.; Korbel, G.A. Using a Small Molecule Inhibitor of Peptide:N-Glycanase to Probe Its Role in Glycoprotein Turnover. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 1677–1687.

- Kim, H.M.; Han, J.W.; Chan, J.Y. Nuclear Factor Erythroid-2 Like 1 (NFE2L1): Structure, function and regulation. Gene 2016, 584, 17–25.

- Steffen, J.; Seeger, M.; Koch, A.; Krüger, E. Proteasomal Degradation Is Transcriptionally Controlled by TCF11 via an ERAD-Dependent Feedback Loop. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 147–158.

- Lehrbach, N.; Breen, P.C.; Ruvkun, G. Protein Sequence Editing of SKN-1A/Nrf1 by Peptide:N-Glycanase Controls Proteasome Gene Expression. Cell 2019, 177, 737–750.e15.

- Lehrbach, N.; Ruvkun, G. Proteasome dysfunction triggers activation of SKN-1A/Nrf1 by the aspartic protease DDI-1. eLife 2016, 5, e17721.

- Koizumi, S.; Irie, T.; Hirayama, S.; Sakurai, Y.; Yashiroda, H.; Naguro, I.; Ichijo, H.; Hamazaki, J.; Murata, S. The aspartyl protease DDI2 activates Nrf1 to compensate for proteasome dysfunction. eLife 2016, 5, e18357.

- Murphy, P.; Kolstø, A.-B. Expression of the bZIP transcription factor TCF11 and its potential dimerization partners during development. Mech. Dev. 2000, 97, 141–148.

- Delporte, C.; Bryla, A.; Perret, J. Aquaporins in Salivary Glands: From Basic Research to Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 166.

- Zhi, H.; Yuan, W.-T. Expression of aquaporin 3, 4, and 8 in colonic mucosa of rat models with slow transit constipation. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi = Chin. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2011, 14, 1124–1130.

- Galeone, A.; Han, S.Y.; Huang, C.; Hosomi, A.; Suzuki, T.; Jafar-Nejad, H. Tissue-specific regulation of BMP signaling by Drosophila N-glycanase 1. eLife 2017, 6, e27612.

- Galeone, A.; Adams, J.; Matsuda, S.; Presa, M.F.; Pandey, A.; Han, S.Y.; Tachida, Y.; Hirayama, H.; Vaccari, T.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Regulation of BMP4/Dpp retrotranslocation and signaling by deglycosylation. eLife 2020, 9, e55596.

- Bakrania, P.; Efthymiou, M.; Klein, J.C.; Salt, A.; Bunyan, D.J.; Wyatt, A.; Ponting, C.P.; Martin, A.; Williams, S.; Lindley, V.; et al. Mutations in BMP4 Cause Eye, Brain, and Digit Developmental Anomalies: Overlap between the BMP4 and Hedgehog Signaling Pathways. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 304–319.

- Obara-Ishihara, T.; Kuhlman, J.; Niswander, L.; Herzlinger, D. The surface ectoderm is essential for nephric duct formation in intermediate mesoderm. Development 1999, 126, 1103–1108.

- Tirosh-Finkel, L.; Zeisel, A.; Brodt-Ivenshitz, M.; Shamai, A.; Yao, Z.; Seger, R.; Domany, E.; Tzahor, E. BMP-mediated inhibition of FGF signaling promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation of anterior heart field progenitors. Development 2010, 137, 2989–3000.

- Reis, L.M.; Tyler, R.C.; Schilter, K.F.; Abdul-Rahman, O.; Innis, J.W.; Kozel, B.A.; Schneider, A.S.; Bardakjian, T.M.; Lose, E.J.; Martin, D.M.; et al. BMP4 loss-of-function mutations in developmental eye disorders including SHORT syndrome. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 130, 495–504.

- Kong, J.; Peng, M.; Ostrovsky, J.; Kwon, Y.J.; Oretsky, O.; McCormick, E.M.; He, M.; Argon, Y.; Falk, M.J. Mitochondrial function requires NGLY1. Mitochondrion 2017, 38, 6–16.

- Han, S.Y.; Pandey, A.; Moore, T.; Galeone, A.; Duraine, L.; Cowan, T.M.; Jafar-Nejad, H. A conserved role for AMP-activated protein kinase in NGLY1 deficiency. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1009258.

- Talsness, D.M.; Owings, K.G.; Coelho, E.; Mercenne, G.; Pleinis, J.M.; Partha, R.; A Hope, K.; Zuberi, A.R.; Clark, N.L.; Lutz, C.M.; et al. A Drosophila screen identifies NKCC1 as a modifier of NGLY1 deficiency. eLife 2020, 9, e27831.

- Rusan, Z.M.; Kingsford, O.A.; Tanouye, M.A. Modeling Glial Contributions to Seizures and Epileptogenesis: Cation-Chloride Cotransporters in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101117.

- Singh, R.; Almutairi, M.M.; Pacheco-Andrade, R.; Almiahuob, M.Y.M.; Di Fulvio, M. Impact of Hybrid and Complex N-Glycans on Cell Surface Targeting of the Endogenous Chloride Cotransporter Slc12a2. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 2015, 505294.

- Lipiński, P.; Bogdańska, A.; Różdżyńska-Świątkowska, A.; Wierzbicka-Rucińska, A.; Tylki-Szymańska, A. NGLY1 deficiency: Novel patient, review of the literature and diagnostic algorithm. JIMD Rep. 2020, 51, 82–88.

- Abuduxikuer, K.; Zou, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.-S. Novel NGLY1 gene variants in Chinese children with global developmental delay, microcephaly, hypotonia, hypertransaminasemia, alacrimia, and feeding difficulty. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 65, 387–396.

- Suzuki, T.; A Kwofie, M.; Lennarz, W.J. Ngly1, a mouse gene encoding a deglycosylating enzyme implicated in proteasomal degradation: Expression, genomic organization, and chromosomal mapping. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 304, 326–332.

- Asahina, M.; Fujinawa, R.; Hirayama, H.; Tozawa, R.; Kajii, Y.; Suzuki, T. Reversibility of motor dysfunction in the rat model of NGLY1 deficiency. Mol. Brain 2021, 14, 91.

- Fujihira, H.; Masahara-Negishi, Y.; Tamura, M.; Huang, C.; Harada, Y.; Wakana, S.; Takakura, D.; Kawasaki, N.; Taniguchi, N.; Kondoh, G.; et al. Lethality of mice bearing a knockout of the Ngly1-gene is partially rescued by the additional deletion of the Engase gene. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006696.

- Yoshida, Y.; Chiba, T.; Tokunaga, F.; Kawasaki, H.; Iwai, K.; Suzuki, T.; Ito, Y.; Matsuoka, K.; Yoshida, M.; Tanaka, K.; et al. E3 ubiquitin ligase that recognizes sugar chains. Nature 2002, 418, 438–442.

- Bi, Y.; Might, M.; Vankayalapati, H.; Kuberan, B. Repurposing of Proton Pump Inhibitors as first identified small molecule inhibitors of endo -β- N -acetylglucosaminidase (ENGase) for the treatment of NGLY1 deficiency, a rare genetic disease. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 2962–2966.

- Yoshida, Y.; Asahina, M.; Murakami, A.; Kawawaki, J.; Yoshida, M.; Fujinawa, R.; Iwai, K.; Tozawa, R.; Matsuda, N.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Loss of peptide:N-glycanase causes proteasome dysfunction mediated by a sugar-recognizing ubiquitin ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2102922118.

- Yang, K.; Huang, R.; Fujihira, H.; Suzuki, T.; Yan, N. N-glycanase NGLY1 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and inflammation through NRF1. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 2600–2616.

- Kwak, M.-K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Greenlaw, J.L.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W. Antioxidants Enhance Mammalian Proteasome Expression through the Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 8786–8794.

- East, D.A.; Fagiani, F.; Crosby, J.; Georgakopoulos, N.D.; Bertrand, H.; Schaap, M.; Fowkes, A.; Wells, G.; Campanella, M. PMI: A ΔΨm Independent Pharmacological Regulator of Mitophagy. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 1585–1596.

- Pajares, M.; Jiménez-Moreno, N.; García-Yagüe, J.; Escoll, M.; de Ceballos, M.L.; Van Leuven, F.; Rábano, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Rojo, A.I.; Cuadrado, A. Transcription factor NFE2L2/NRF2 is a regulator of macroautophagy genes. Autophagy 2016, 12, 1902–1916.

- Kensler, T.W.; Wakabayashi, N.; Biswal, S. Cell Survival Responses to Environmental Stresses Via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE Pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 89–116.