Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kwan Ho WONG | -- | 1541 | 2022-06-16 11:28:42 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | -7 word(s) | 1534 | 2022-06-17 03:32:48 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Wong, K.H.; Wu, H.; , .; Hui, J.H.L.; Shaw, P.; Lau, D. Hyacinthus orientalis L.. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24109 (accessed on 04 March 2026).

Wong KH, Wu H, , Hui JHL, Shaw P, Lau D. Hyacinthus orientalis L.. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24109. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Wong, Kwan Ho, Hoi-Yan Wu, , Jerome Ho Lam Hui, P.c. Shaw, David Lau. "Hyacinthus orientalis L." Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24109 (accessed March 04, 2026).

Wong, K.H., Wu, H., , ., Hui, J.H.L., Shaw, P., & Lau, D. (2022, June 16). Hyacinthus orientalis L.. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24109

Wong, Kwan Ho, et al. "Hyacinthus orientalis L.." Encyclopedia. Web. 16 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Hyacinthus orientalis L., commonly known as hyacinth, is one of the most important cultivated plants around the world. The cultivars of this species are characterised by their flowers with strong fragrances and a wide range of attractive colours, which make them a beloved option among ornamentals. The chloroplast genomes of Hyacinthus cultivars ranged from 154,458 bp to 154,641 bp, while those of Bellevalia paradoxa and Scilla siberica were 154,020 bp and 154,943 bp, respectively. Each chloroplast genome was annotated with 133 genes, including 87 protein-coding genes, 38 transfer RNA genes and 8 ribosomal RNA genes.

Hyacinthus orientalis

hyacinth

Scilla siberica

Bellevalia paraxoda

chloroplast genome

cultivar phylogeny

geophytes

Asparagaceae

Scilloideae

Hyacinthaceae

1. Taxonomy of Hyacinthus orientalis L.

1.1. Morphology

Hyacinthus orientalis L., commonly known as hyacinth, is one of the most important cultivated plants around the world [1][2][3]. The cultivars of this species are characterised by their flowers with strong fragrances [1][4][5][6][7][8][9] and a wide range of attractive colours [1][4][5][7][10][11], which make them a beloved option among ornamentals [7][8][9].

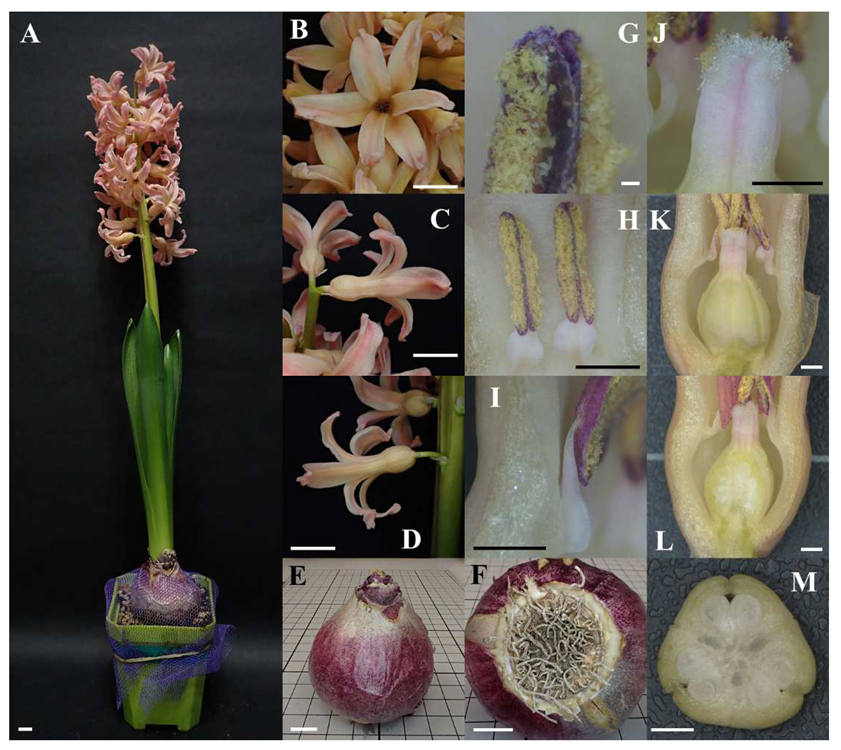

As a geophyte [3][12], the hyacinth has a significant, globose bulb [5] (Figure 1A,E) which is modified from its stem and leaves [13][14]. Its stem is shrunken and flattened as the disc (Figure 1F), while the modified leaves become scale leaves [13][14] (Figure S1) acting as the storage of nutrients [7]. The bulb of the hyacinth is tunicate [4][5], meaning that the outermost layers of scale leaves turn into a thin and dry cover called a tunic to protect the inner, fresh scale leaves [13][15]. The outer tunics of the hyacinth show different colours depending on cultivars [5], which can be generally classified into three major colours: dark purple, beige-to-white, and silvery purple.

Figure 1. Overview and close-up photos of Hyacinthus orientalis L. ‘Gipsy Queen’. (A) Overview of an individual of Hyacinthus orientalis L. ‘Gipsy Queen’ (scale bar = 1 cm). (B–D) The corolla (scale bar = 1 cm). (B) Front view. (C) Side view of corolla on the upper inflorescence. (D) Side view of corolla on the lower inflorescence. (E,F) The bulb (scale bar = 1 cm). (E) Side view of the bulb of which tunic is in slivery purple. (F) The disc with remnant roots. (G–I) Androecium. (G) Pollen sacs under microscopy (scale bar = 0.01 cm). (H) Stamens (scale bar = 0.1 cm). (I) Filaments of dorsifixed anthers (scale bar = 0.1 cm). (J–M) Gynoecium (scale bar = 0.1 cm). (J) Receptive papilla on the stigma. (K) Superior ovary. (L) Longitudinal section of the ovary showing axile placentation. (M) Cross section of the ovary showing ovules in three locules.

The inflorescence of the hyacinth is a raceme with 2 to 40 flowers on a single scape [1][5] (leafless stalk arising from ground level [13][15]). The number and density of flowers vary across cultivars. Wild populations of Hyacinthus orientalis blossom in comparatively looser scapes, bearing fewer flowers in a blue colour [5][16]. Cultivars of hyacinths have flowers in different colours [1][4][5][6][8][9][10][17][18][19], including red, pink, orange, yellow, white, blue and purple. The flower normally has six tepals arranged in two whorls (P3+3) (Figure 1B), which are basally united forming a perianth tube (Figure 1C,D) and constricted above the trilocular superior ovary (G(3)) [5] with axile placentation (Figure 1L,M). The perianth lobes are oblong–spathulate in shape, spreading to recurved [5][10]. Stamens of the hyacinth are in the same number as tepals (A3+3) and attached to the tepals while not reaching to the throat of the perianth tube [5]. The linear, longitudinally dehiscent dorsifixed anthers are longer than the filaments [5] (Figure 1H,I) and show different colours depending on the cultivars [19]. Different cultivars of hyacinths can either blossom with single or double flowers [16][18][19][20].

Hyacinths originate from the Mediterranean region, including Turkey, Syria and Lebanon [1][5][10][19][21]. In Turkey, the species naturally inhabits rocky limestone slopes and scrubs [21]. The species is also found in Israel where it appears in small stands under the shade of maquis among rocks [12][22].

1.2. Nomenclature

The scientific name Hyacinthus orientalis L. was first published by Carl Linnaeus in 1753 in Species Plantarum [23]. The species has an indispensable role in the nomenclature of related taxa. Being the type species of the genus Hyacinthus L., Hyacinthus orientalis L. also represented the family Hyacinthaceae Batsch ex Borkh. as Hyacinthus L. is the designated type genus [24][25]. The family was proposed by Borkhausen in 1797 [26] and has been recognised by several taxonomists and taxonomic systems including Dahlgren et al. in 1985 [27], Conran et al. in 2005 [10], the NCBI Taxonomy system [28] and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) II system in 2003 [29]. However, since 2009, the APG system has adopted broader limits for organising the families in Asparagales [30][31]. The family Hyacinthaceae was included in the family Asparagaceae sensu lato and ranked as a subfamily [30][31][32]. According to the International Code for Nomenclature of Plants, Algae and Fungi (ICN), no conserved names are allowed for taxa below family level [33]. Since the subfamily name Hyacinthoideae (Link, 1829) [34] had been previously adopted, according to the priority of names in ICN, the subfamily name Scilloideae (Burnett, 1835) [35] was adopted for such inclusion [32].

2. Cultivation of Hyacinthus orientalis L.

2.1. History of Cultivation

The cultivation of hyacinth is long-standing with 460 years of history. The earliest record can be traced back to 1562, when the hyacinth was imported from Turkey to Eastern Europe [20]. At the end of sixteenth century, the hyacinth was introduced into England as a cultivated plant [36]. Cultivars of hyacinths were produced through either hybridisation or mutation [7][11]. The climax of hyacinth cultivation should be dated back to the 1760s, when over 2000 cultivars of hyacinths were recorded in the French Monograph Des Jacintes de Leur Anatomie Reproduction et Culture published by Saint Simon in 1768 [14]. However, most of these cultivars were unable to survive [20].

2.2. Nomenclatural Circumscription of Hyacinthus Cultivars

Homonyms and synonyms of cultivar epithets are serious issues in the nomenclature of Hyacinthus cultivars [8][11][16][20]. Distinct cultivars have shared an identical cultivar epithet, causing the problem of homonyms. For example, three cultivars with single blue flowers from three different origins—Haarlem, Overveen and Hillegom—shared the epithet ‘Queen of the Blues’ [16]. Another cultivar epithet ‘Grand Vainqueur’ was severely abused, as almost all colours of flowers, regardless of single or double, were called this epithet [16]. In contrast, a single cultivar was given two or more cultivar epithets, causing the problem of synonyms. For example, the registered ‘Orange Boven’ was given the unaccepted epithet ‘Salmonetta’ [20]; the registered ‘China Pink’ was misapplied with the epithet ‘Delft Pink’ [19]; the registered ‘Kroonprinses Margaretha’ was given two misapplied epithets, ‘Crownprincess Margareth’ and ‘Margareth’ [19].

Since 1955, Koninklijke Algemeene Vereeniging voor Bloembollencultuur (KAVB) in the Netherlands was appointed as an International Cultivar Registration Authority (ICRA) for hyacinths by the International Society of Horticulture (ISHS) Commission for Nomenclature and Cultivar Registration [37][38]. In the International Checklist for Hyacinths and Miscellaneous Bulbs published by KAVB in 1991, there were 202 registered cultivars of hyacinths [19]. In 1993, about 50 cultivars were commercialised in floricultural production [7]. As of 1 January 2020, 368 registered cultivars of hyacinths were recorded in the database of KAVB [39]. According to the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP), for the plants governed by ICRA, each cultivar can only be given one accepted name [38].

3. Recent Molecular Insight into Hyacinthus Cultivars and the Potentiality of Chloroplast Genomes for Cultivar Phylogeny

The compatibility of cross-fertilisation and phylogenetic relationships among the Hyacinthus cultivars have been studied by karyotypic [8][11][20][40][41][42] and molecular means [9][43], respectively. The diversity of chromosomal karyotypes was characterised in Hyacinthus cultivars, which can be diploid, triploid, tetraploid and aneuploid [8][20][40]. It is difficult to identify the authenticity of hybrid offspring in hyacinths ascribed by their richness of chromosomal ploidy variation and also the greater chances to obtain hybrid offspring from parents with higher ploidy [8][20][42][43]. As the hyacinth grows only in the right season and starts to blossom in the 2nd to 3rd year from seeds [2][4], the cost of breeding a new cultivar can be greatly reduced by early identification and selection [43].

The research group of Hu et al. utilised twelve Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) molecular markers to analyse the phylogenetic relationships of 29 Hyacinthus cultivars [9]. In their unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) tree, cultivars with the same colour were mostly grouped into the same cluster. They concluded that the phylogenetic relationships among Hyacinthus cultivars had a correlation with the flower colours to a certain extent [9]. The research group continued to identify hyacinth hybrid progeny using the twelve ISSR molecular markers [43]. The authenticity of hybrid offspring was assured by the presence of parental bands and offspring-unique bands in the electrophoresis diagram of the ISSR analysis [43].

With recent technological advancements, the assembly of complete chloroplast genomes has become more feasible. Apart from resolving phylogenetic problems [44][45][46][47], chloroplast genomes were recently applied in studying ornamental plants such as Lilium L. [48][49], Camellia L. [50], Lagerstroemia L. [51], Meconopsis Vig. [52] and Paeonia L. [53]. The chloroplast genomes were utilised to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationship in horticultural species [48][49][50] and sometimes even up to the cultivar level [51][54][55].

Currently, only six complete chloroplast genomes of Scilloideae are available, including three of Barnardia japonica (Thunb.) Schult. et Schult. f. (NC_035997 = KX822775, MH287351 [56] and MT319125 [57]), one of Hyacinthoides non-scripta (L.) Chouard ex Rothm. (NC_046498 = MN824434) [58], one of Albuca kirkii (Baker) Brenan (NC_032697 = KX931448) [59] and one of Oziroe biflora (Ruiz et Pav.) Speta (NC_032709 = KX931463) [59]. It a report to present the chloroplast genomes of the genus Hyacinthus L., Bellevalia Lapeyr. and Scilla L., which were members of Scilloideae of Asparagaceae sensu APG IV. In total, nine chloroplast genomes were sequenced and assembled using Illumina sequencing technology, providing important germplasm resources and insight for the cultivar breeding of the hyacinth and its relatives.

References

- Yeo, P.F. Hyacinthus Linnaeus. In The European Garden Flora, 1st ed.; Walters, S.M., Brady, A., Brickell, C.D., Cullen, J., Green, P.S., Lewis, J., Matthews, V.A., Webb, D.A., Yeo, P.F., Alexander, J.C.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 1986; Volume I, p. 221. ISBN 0-521-24859-0. (hardback).

- Shen, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhu, H.X.; Gu, J.J. Tulips and Hyacinths, 1st ed.; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2004; ISBN 9787503836473.

- Çığ, A.; Başdoğan, G. In vitro Propagation Techniques for Some Geophyte Ornamental Plants with High Economic Value. Int. J. Second. Metab. 2015, 2, 27–49.

- Bailey, L.H.; Bailey, E.Z. Hyacinthus L. In Hortus Third: A Concise Dictionary of Plants Cultivated in the United States and Canada, 1st ed.; Macmillian Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA; Collier Macmillan Publisher: London, UK, 1976; p. 577.

- The Royal Horticultural Society. The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening, 1st ed.; Huxley, A., Griffiths, M., Levy, M., Eds.; The Macmillan Press Limited: London, UK; The Stockton Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 604–605. ISBN 1-56159-001-0.

- The Royal Horticultural Society. The Royal Horticultural Society Plant Guides: Bulbs, 1st ed.; Dorling Kindersley Publishers Ltd: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 9780751303056.

- Nowak, J.; Rudnicki, R.M. Hyacinthus. In The Physiology of Flower Bulbs, 1st ed.; de Hertogh, A., le Nard, M., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 335–347. ISBN 0-444-87498-4.

- Hu, F.R.; Liu, H.H.; Wang, F.; Bao, R.L.; Liu, G.X. Root tip chromosome karyotype analysis of hyacinth cultivars. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 10863–10876.

- Hu, F.R.; Hu, Y.M.; Wang, F.; Ren, C. Genetic Diversity of 29 Hyacinth Germplasm Resources Revealed by Using ISSR Markers. Mol. Plant Breed. 2015, 13, 379–385.

- Conran, J. Family Hyacinthaceae. In Horticultural Flora of South-Eastern Australia, 1st ed.; Spencer, R., Ed.; University of New South Wales Press Ltd: Sydney, Australia, 2005; Volume 5, pp. 349–367. ISBN 0868408328.

- Hu, F.R.; Ren, C.; Bao, R.L.; Liu, G.X. Chromosomes analysis of five diploid garden Hyacinth species. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 13, 82–87.

- Danin, A.; Fragman-Sapir, O. Hyacinthus orientalis L. In Flora of Israel Online. 2016. Available online: https://flora.org.il/en/plants/hyaori/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Hickey, M.; King, C. The Cambridge Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN1 ISBN-13: 978-0-521-79401-5. ISBN2 ISBN-10: 0-521-79401-3.

- Saint-Simon, M.H. Des Jacintes de Leur Anatomie Reproduction et Culture, 1st ed.; De Límprimerie de C. Eel: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1768.

- Beentjie, H. The Kew Plant Glossary, 2nd ed.; Kew Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-84246-604-9.

- Kersten, H.J.H. The cultivation of the hyacinth in Holland. J. R. Hortic. Soc. Lond. 1889, 11, 54–63. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/164536 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Zhao, Z.Z.; Yang, P.P.; Chen, Q.Q.; Yu, J.J.; Wu, C.Z. Study on Phenophase and Growth Characteristics of 12 Cultivars of Hyacinthus orientalis. J. Kashi Univ. 2019, 40, 111–115.

- Pasztor, R.; Bala, M.; Sala, F. Flowers quality in relation to planting period in some hyacinth cultivars. AgroLife Sci. J. 2020, 9, 263–272. Available online: http://agrolifejournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.IX_1/Art33.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Van Scheepen, J. International Checklist for Hyacinths and Miscellaneous Bulbs; Royal General Bulbgrowers’ Association: Hillegom, The Netherlands, 1991; ISBN 90-73350-01-8.

- Darlington, C.; Hair, J.; Hurcombe, R. The history of the garden hyacinths. Heredity 1951, 5, 233–252.

- Wendelbo, P. Hyacinthus L. In Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands, 1st ed.; Davis, P., Mill, R., Tan, K., Eds.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1984; Volume 8, pp. 263–264. ISBN 0-85224-494-0.

- Horovitz, A.; Danin, A. Relatives of ornamental plants in the flora of Israel. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 1983, 32, 75–95. Available online: https://flora.org.il/en/articles/relatives-of-ornamental-plants-in-the-flora-of-israel-2/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Linnaei, C. Hyacinthus. In Species Plantarum, 1st ed.; Impensis Laurentii Salvii: Holmiae, Sweden, 1753; Tomus I; pp. 316–318.

- Missouri Botanical Garden. Hyacinthaceae Batsch ex Borkh. 2022. Available online: https://tropicos.org/name/50324572 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Missouri Botanical Garden. Hyacinthus L. 2022. Available online: https://www.tropicos.org/name/40028561 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Borkhausen, M.B. Hyacinthinae Batsch. In Botanisches Wörterbuch, 1st ed.; G.F. Heyer: Giessen, Germany, 1797; Volume 1, p. 315.

- Dahlgren, R.M.T.; Clifford, H.T.; Yeo, P.F.; Faden, R.B.; Jacobsen, N.; Jakobsen, K.; Jensen, S.R.; Nielsen, B.J.; Rasmussen, F.N. Hyacinthaceae Batsch (1802). In The Families of the Monocotyledons: Structure, Evolution, and Taxonomy, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Tokyo, Japan, 1985; pp. 188–193. ISBN 3-540-13655-X.

- Schoch, C.L.; Ciufo, S.; Domrachev, M.; Hotton, C.L.; Kannan, S.; Khovanskaya, R.; Leipe, D.; Mcveigh, R.; O’Neill, K.; Robbertse, B.; et al. NCBI Taxonomy: A comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database 2020, 2020, baaa062.

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2003, 141, 399–436.

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009, 161, 105–121.

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 1–20.

- Chase, M.W.; Reveal, J.L.; Fay, M.F. A subfamilial classification for the expanded asparagalean families Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae and Xanthorrhoeaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009, 161, 132–136.

- McNeill, J.; Barrie, F.R.; Burdet, H.M.; Demoulin, V.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Marhold, K.; Nicolson, D.H.; Prado, J.; Silva, P.C.; Skog, J.E.; et al. International code of botanical nomenclature—Vienna Code. Regnum Veg. 2006, 146, 29–32. Available online: https://www.iapt-taxon.org/historic/2006.htm (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Link, J.H.F. Subordo 2. Hyacinthinae. Hyacinthartige. In Handbuch zur Erkennung der Nutzbarsten und am Häufigsten Vorkommenden Gewächse, 1st ed.; Spenerschen Buchhandlung: Berlin, Germany, 1829; p. 160.

- Burnett, G.T. Scillidae. In Outlines of Botany, including a General History of the Vegetable Kingdom. In which Plants Are Arranged According to the System of Natural Affinities; John Churchill: London, UK, 1835; Volume 1, p. 428. Available online: https://archive.org/details/b28742631_0001/page/428/mode/2up (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Douglas, J. The Hyacinth from an English Point of View. J. R. Hortic. Soc. Lond. 1889, 11, 63–70. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/164536 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- International Society for Horticultural Science. ICRA Report Sheet. Royal General Bulbgrowers’ Association (K.A.V.B.). Available online: https://www.ishs.org/sci/icralist/49.htm (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- International Society for Horticultural Science. International Society for Horticultural Science. International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP). In Scripta Horticulturae, 9th ed.; International Society for Horticultural Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2016; Volume 18, ISBN1 978-94-6261-116-0. Available online: https://www.ishs.org/sites/default/files/static/ScriptaHorticulturae_18.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022)ISBN2 978-94-6261-116-0.

- Koninklijke Algemeene Vereeniging voor Bloembollencultuur; Search/Zoekopdracht: Hyacinthus, Zoekresultaten. Available online: https://www.kavb.nl/zoekresultaten (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Darlington, C.D.; Mather, K. Chromosome balance and interaction in Hyacinthus. J. Genet. 1944, 46, 52–61.

- Brat, S. Fertility and selection in hyacinth I. Gametic selection. Heredity 1967, 22, 597–601.

- Brat, S. Fertility and selection in garden hyacinth II. Zygotic selection. Heredity 1969, 24, 189–202.

- Hu, F.R.; He, G.R.; Wang, F.; Ren, C. The Identification of the Hyacinth Hybrid Progeny by the Method of ISSR Molecular Marker. Mol. Plant Breed. 2015, 13, 1336–1342.

- Jansen, R.K.; Cai, Z.; Raubeson, L.A.; Daniell, H.; Depamphilis, C.W.; Leebens-Mack, J.; Muller, K.F.; Guisinger-Bellian, M.; Haberle, R.C.; Hansen, A.K.; et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19369–19374.

- Hernandez-Leonl, S.; Gernandt, D.S.; Perez de la Rosa, J.A.; Jardon-Barbolla, L. Phylogenetic relationships and species delimitation in Pinus section Trifoliae inferred from plastid DNA. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 1–14.

- Li, X.W.; Yang, Y.; Henry, R.J.; Rossetto, M.; Wang, Y.T.; Chen, S.L. Plant DNA barcoding: From gene to genome. Biol. Rev. 2015, 90, 157–166.

- Williams, A.V.; Miller, J.T.; Small, I.; Nevill, P.G.; Boykin, L.M. Integration of complete chloroplast genome sequences with small amplicon datasets improves phylogenetic resolution in Acacia. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 96, 1–8.

- Du, Y.P.; Bi, Y.; Yang, F.P.; Zhang, M.F.; Chen, X.Q.; Xue, J.; Zhang, X.H. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Lilium: Insights into evolutionary dynamics and phylogenetic analyses. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5751.

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.I.; Kim, B.R.; Choi, I.Y.; Ryser, P.; Kim, N.S. Chloroplast genomes of Lilium lancifolium, L. amabile, L. callosum, and L. philadelphicum: Molecular characterization and their use in phylogenetic analysis in the genus Lilium and other allied genera in the order Liliales. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–15.

- Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Guo, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, K. Complete chloroplast genome of Camellia japonica genome structures, comparative and phylogenetic analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–18.

- Xu, C.; Dong, W.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Xie, X.; Jin, X.; Shi, J.; He, K.; Suo, Z. Comparative Analysis of Six Lagerstroemia Complete Chloroplast Genomes. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–12.

- Li, X.; Tan, W.; Sun, J.; Du, J.H.; Zheng, C.G.; Tian, X.X.; Zheng, M.; Xiang, B.B.; Wang, Y. Comparison of Four Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Medicinal and Ornamental Meconopsis Species: Genome Organization and Species Discrimination. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10567.

- Zhou, X.J.; Zhang, K.; Peng, Z.F.; Sun, S.S.; Ya, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Cheng, Y.W. Comparative Analysis of Chloroplast Genome Characteristics between Paeonia jishanensis and Other Five Species of Paeonia. Lin Ye Ke Xue 2020, 56, 82–88. Available online: http://www.linyekexue.net/EN/10.11707/j.1001-7488.20200409 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Chen, J.L.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Zhao, K. Chloroplast genome of Prunus campanulata ‘Fei han’ (Rosaceae), a new cultivar in the modern cherry breeding. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 2020, 5, 1369–1371.

- Xia, H.; Xu, Y.; Liao, B.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, F. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a Chinese traditional cultivar in Chrysanthemum, Chrysanthemum morifolium ’Anhuishiliuye’. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2021, 6, 1281–1282.

- Wang, R.H.; Gao, J.; Li, M.; Wu, X.; Shen, C.; Wu, J.; Qi, Z.C.; Li, P. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of Barnardia japonica (Thunb.) Schult. and Schult.f. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2018, 3, 697–698.

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Lin, N.; Xia, M. The complete plastome and phylogeny of Barnardia japonica (Asparagaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2020, 5, 2640–2641.

- Garnett, G.J.L.; Könyves, K.; Bilsborrow, J.; David, J.; Culham, A. The complete plastome of Hyacinthoides non-scripta (L.) Chouard ex Rothm. (Asparagaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2020, 5, 1003–1004.

- McKain, M.R.; McNeal, J.R.; Kellar, P.R.; Eguiarte, L.E.; Pires, J.C.; Leebens-Mack, J. Timing of rapid diversification and convergent origins of active pollination within Agavoideae (Asparagaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2016, 103, 1717–1729.

More

Information

Subjects:

Horticulture

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

3.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

17 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No