Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brian James Holoyda | -- | 1587 | 2022-06-16 04:53:00 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1587 | 2022-06-16 04:58:41 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Holoyda, B.J. Current State of Bestiality Law in the US. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24086 (accessed on 03 March 2026).

Holoyda BJ. Current State of Bestiality Law in the US. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24086. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Holoyda, Brian James. "Current State of Bestiality Law in the US" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24086 (accessed March 03, 2026).

Holoyda, B.J. (2022, June 16). Current State of Bestiality Law in the US. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24086

Holoyda, Brian James. "Current State of Bestiality Law in the US." Encyclopedia. Web. 16 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Laws punishing individuals who have sex with nonhuman animals have existed since the earliest written legal codes. In the United States, bestiality has long been prohibited. The rationale for criminalizing sex acts with animals has changed over time and has included moral condemnation, considerations of animal rights and animal welfare, and most recently, a concern about the relationship between animal cruelty and interpersonal violence, colloquially known as the Link. There exist important differences in language, specificity, and potential punishments for offenders depending on the jurisdiction.

animal sexual abuse

animal cruelty

bestiality

1. State Statutes

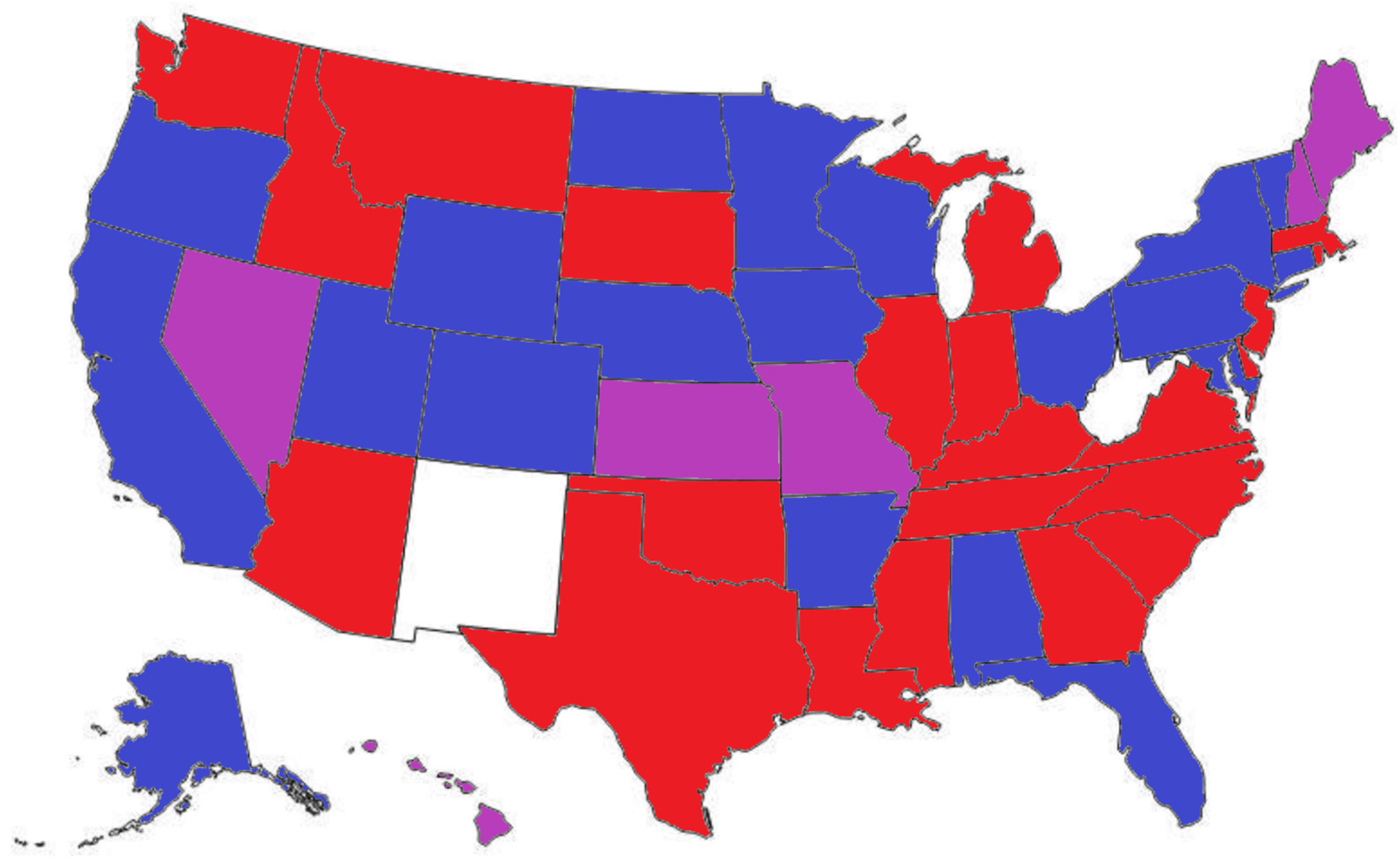

In 2014, a review of state statutes prohibiting bestiality was conducted [1]. At the time, only 31 states had laws criminalizing the behavior, of which 16 imposed a felony and 15 imposed a misdemeanor. Since that time, the legal landscape has changed dramatically. Now all states except New Mexico and West Virginia have statutes that impose sanctions for sexual acts with animals [2]. Twenty-three states impose a misdemeanor, 25 impose a felony, and many states now have felony enhancements for specific sexual acts, for example, coercing a minor to engage in bestiality or for those with prior convictions. Figure 1 is a map of the United States with the jurisdictions defined based on the severity of a conviction for bestiality. Some new laws also require that the individual who is convicted undergo a psychological assessment or face other sanctions, for example, forfeiture of pets or other animals.

Figure 1. Jurisdictions that prohibit bestiality in the United States. States imposing a misdemeanor in blue, a misdemeanor with felony enhancements in purple, and a felony in red.

The titles of state statutes criminalizing bestiality differ significantly, which suggests both the time in which the law was established and the motivation for prohibiting the behavior at that time. Rhode Island’s “abominable and detestable crime against nature” [3] was, predictably, established in 1896. The language of the statute suggests that considerations regarding morality and decency likely motivated the passage of the law. Similarly, Mississippi’s law of “unnatural intercourse” [4] falls under Chapter 29, “Crimes Against Public Morals and Decency” and appears to criminalize consensual anal intercourse between adult humans. This law can be traced back to 1930 or earlier. Alternatively, laws categorizing bestiality as animal cruelty or sexual assault tend to be more recent. California amended its law to “sexual contact with animals” in 2019 [5], whereas Hawaii passed its first bestiality law, “sexual assault of an animal” [6], in 2021.

The laws in different jurisdictions across the United States vary in important ways, not just in the title of the statute. Newer laws that utilize modern language tend to provide more granularity regarding the specific acts that are illegal. New Jersey, for example, amended its animal cruelty statute in 2015 to clearly define which sexual behaviors are illegal. The statute states:

It shall be unlawful to … use, or cause or procure the use of, an animal or creature in any kind of sexual manner or initiate any kind of sexual contact with the animal or creature, including, but not limited to, sodomizing the animal or creature. As used in this paragraph, “sexual contact” means any contact between a person and an animal by penetration of the penis or a foreign object into the vagina or anus, contact between the mouth and genitalia, or by contact between the genitalia of one and the genitalia or anus of the other. This term does not include any medical procedure performed by a licensed veterinarian practicing veterinary medicine or an accepted animal husbandry practice [7].

New Jersey’s law is arguably better than those that fail to define unsanctioned behaviors for prosecutorial reasons. First, it clarifies what actual behaviors can result in a charge or conviction. Laws criminalizing the “crime against nature,” on the other hand, contain outdated language that lends itself to various interpretations. Many of these laws conflate bestiality with consensual anal intercourse, clearly targeting male homosexual behavior. Such a connection warrants restructuring of legislation to more specifically focus on acts of bestiality. Second, clear statutory language may assist veterinarians, police, and prosecutors involved in the investigation of bestiality claims. Identification of the relevant organs can aid veterinarians who may have to collect physical evidence in such cases [8]. As Stern and Smith-Blackmore note, “Data obtained from the forensic necropsy should be documented so that it can be viewed or re-created by others and meet the standards required for legal proceedings” [9] (p. 1059), highlighting the potential benefit of legislative specificity for those involved in bestiality investigations.

In addition to criminalizing sexual acts with animals, some state statutes criminalize additional behaviors related to bestiality. An example of this type of legislation is Wisconsin’s statute, amended in 2019. The law defines a variety of behaviors that may be grounds for prosecution, including those that do not involve sexual contact. The law reads:

No person may knowingly do any of the following:Engage in sexual contact with an animal.Advertise, offer, accept an offer, sell, transfer, purchase, or otherwise obtain an animal with the intent that it be used for sexual contact in this state.Organize, promote, conduct, or participate as an observer of an act involving sexual contact with an animal.Permit sexual contact with an animal to be conducted on any premises under his or her ownership or control.Photograph or film obscene material depicting a person engaged in sexual contact with an animal.Distribute, sell, publish, or transmit obscene material depicting a person engaged in sexual contact with an animal.Possess with the intent to distribute, sell, publish, or transmit obscene material depicting a person engaged in sexual contact with an animal.Force, coerce, entice, or encourage a child who has not attainted the age of 13 years to engage in sexual contact with an animal.Engage in sexual contact with an animal in the presence of a child who has not attained the age of 13 years.Force, coerce, entice, or encourage a child who has attained the age of 13 years but who has not attained the age of 18 to engage in sexual contact with an animal.Engage in sexual contact with an animal in the presence of a child who has attained the age of 13 years but who has not attained the age of 18 years [10].

The behaviors rendered illegal by Wisconsin’s law are broad. Like child sexual exploitation material (CSEM) laws, the statute criminalizes the dissemination of pornographic material featuring bestiality. In addition, individuals purchasing or selling animals involved in bestiality, organizing or observing bestiality, or permitting bestiality on their premises could all be prosecuted under the law.

Lastly, some state statutes describe additional punishments beyond jail or prison time. Alaskan law, for example, can require those convicted of animal cruelty, including bestiality, to forfeit any affected animals to the state or a custodian, to reimburse the state or custodian for costs related to caring for the animal, and to have their possession of animals prohibited or limited up to ten years [11]. Some states, such as Arizona, have enacted legislation to require individuals convicted of bestiality to undergo psychological assessment and counseling at the convicted person’s expense [12]. This requirement is consistent with the goals of advocates of Link-based law, who contend that animal cruelty is a marker for other forms of interpersonal violence or other antisocial behaviors that can be identified and potentially mitigated through mental health interventions [13]. Finally, some states require offenders to pay a fine, including Louisiana [14], where repeat offenders pay a fine between USD 5,000 and USD 25,000.

2. Federal Legislation

Bestiality has been a crime at the federal level since the 1950′s under the United States Armed Forces Code. The Code states that individuals who engage in “unnatural carnal copulation with an animal” are guilty of bestiality and will be punished through court-martial [15]. In 2019, the U.S. Congress passed the Preventing Animal Cruelty and Torture (PACT) Act. The law criminalizes the creation, sale, and distribution of “crush” videos, or videos depicting cruelty with animals being “crushed, burned, drowned, suffocated, impaled, or otherwise subjected to serious bodily injury” [16] (p. 2) in interstate or foreign commerce. Though some have identified the law as a federal solution that closes a loophole in animal maltreatment legislation [17], others have criticized it as the federalization of what should be state criminal law [18].

3. Law Outside of the United States

The legal status of bestiality around the world is complex. Most nations in the Western world have statutes criminalizing bestiality. Canada modified its statutory definition of bestiality following the high-profile case of R. v. D.L.W. in 2016. D.L.W. was convicted at trial for bestiality for smearing peanut butter on his stepdaughter’s vagina and enticing the family dog to lick it [19]. The Supreme Court overturned the bestiality conviction, however, since his act did not involve actual genital penetration. In response, Senate Bill C-84 was proposed and subsequently received royal assent on 21 June 2019. The law expanded the definition of bestiality to include any contact with an animal for a sexual purpose and expanded punishment to those who commit or compel another to commit bestiality and those who commit bestiality in the presence of a child [20].

In Europe, most nations have laws criminalizing bestiality. Germany, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia, and Slovenia are some exceptions that do not prohibit sexual acts with animals [21]. Among those with bestiality laws, there is wide variability in terms of acts that are punishable and whether other behaviors, such as the distribution or possession of bestiality material, are illegal. Some majority Muslim nations have severe penalties for bestiality, including death [22]. Lastly, the status of bestiality in many parts of the world, such as Africa and some nations in Asia, is unclear.

References

- Holoyda, B.J.; Newman, W.J. Zoophilia and the law: Legal responses to a rare paraphilia. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2014, 42, 412–420.

- Wisch, R.F. Table of State Animal Sexual Assault Laws. Animal Legal & Historical Center. Available online: www.animallaw.info/topic/table-state-animal-sexual-assault-laws (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- General Laws of Rhode Island Annotated; §11-10-1. 1998. Available online: http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/Statutes/TITLE11/11-10/11-10-1.htm (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Mississippi Code Annotated; §97-29-59. 1942. Available online: https://law.justia.com/codes/mississippi/2017/title-97/chapter-29/in-general/section-97-29-59/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- California Penal Code; §286.5. 2019. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=PEN§ionNum=286.5 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Hawaii Revised Statutes; §711-1109.8. 2021. Available online: https://law.justia.com/codes/hawaii/2021/title-37/chapter-711/section-711-1109-8/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- New Jersey Statutes Annotated; Title 4; §22-17. 2017. Available online: https://www.state.nj.us/health/vph/documents/4_22-17%20Text%202018.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Stern, A.W. Animal sexual abuse investigations. In Veterinary Forensic Pathology; Brooks, J.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 121–128.

- Stern, A.W.; Smith-Blackmore, M. Veterinary forensic pathology of animal sexual abuse. Vet Path 2016, 53, 1057–1066.

- Wisconsin Statutes Annotated; §944.18. 2019. Available online: https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/statutes/statutes/944/iii/18/1#:~:text=944.18 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Alaska Statutes Annotated; §11.61.140. 2016. Available online: https://www.akleg.gov/basis/statutes.asp#11.61.140 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Arizona Revised Statutes; §13-1411. 2008. Available online: https://www.azleg.gov/ars/13/01411.htm (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Arkow, P. “Humane criminology”: An inclusive victimology protecting animals and people. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 335.

- Louisiana Revised Statutes; Title 14; §89.3. 2018. Available online: https://legis.la.gov/Legis/Law.aspx?d=1106716 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- United States Code; Title 10; §925. 2016. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title10/pdf/USCODE-2011-title10-subtitleA-partII-chap47-subchapX-sec925.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Preventing Animal Cruelty and Torture Act. 2019. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/724/text (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Animal Welfare Institute. Preventing Animal Cruelty and Torture (PACT) Act. Available online: https://awionline.org/content/preventing-animal-cruelty-and-torture-pact-act (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Stegman, L.S. Do we need to make a federal case out of it? The Preventing Animal Cruelty and Torture Act as over-federalization of criminal law. Am. Crim. Law Rev. 2020, 57, 135–148.

- Canadian Centre for Child Protection. “Bestiality” as Reflected in Canadian Case Law. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/t0dx (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Walker, J. Bill C-84: An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Bestiality and Animal Fighting); Library of Parliament: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020.

- Vetter, S.; Boros, A.; Ozsvari, L. Penal sanctioning of zoophilia in light of the legal status of animals—A comparative analysis of fifteen European countries. Animals 2020, 10, 1024.

- Project on Extra-Legal Executions in Iran. Table of Capital Offenses in the Islamic Republic of Iran, and their Sources in Statute Law and Islamic Law (updated in June 2011). Available online: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CCPR/Shared%20Documents/IRN/INT_CCPR_NGO_IRN_103_9087_E.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2022).

More

Information

Subjects:

Behavioral Sciences

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

99.5K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No