Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elena A. Filonova | -- | 2594 | 2022-06-15 16:15:34 | | | |

| 2 | Elena A. Filonova | + 102 word(s) | 2696 | 2022-06-15 20:04:41 | | | | |

| 3 | Jason Zhu | -2 word(s) | 2694 | 2022-06-16 04:00:33 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Filonova, E.; Medvedev, D. LaAlO3-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolytes. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24071 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Filonova E, Medvedev D. LaAlO3-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolytes. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24071. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Filonova, Elena, Dmitry Medvedev. "LaAlO3-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolytes" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24071 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Filonova, E., & Medvedev, D. (2022, June 15). LaAlO3-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolytes. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24071

Filonova, Elena and Dmitry Medvedev. "LaAlO3-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolytes." Encyclopedia. Web. 15 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) are efficient electrochemical devices that allow for the direct conversion of fuels (their chemical energy) into electricity. Although conventional SOFCs based on yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) electrolytes are widely used from laboratory to commercial scales, the development of alternative ion-conducting electrolytes is of great importance for improving SOFC performance at reduced operation temperatures. The basic information has been researched (synthesis, structure, morphology, functional properties, applications in SOFCs) on representative family of oxygen-conducting electrolytes, such as doped lanthanum aluminates (LaAlO3).

SOFC

solid oxide fuel cells

LaAlO3

lanthanum aluminate

oxygen-ion conductors

solid electrolytes

1. Introduction

The long-term goal of a large body of relevant scientific research is to find a solution to the problem of providing industrial and domestic human needs with renewable and environmentally friendly energy [1][2]. The main fields of sustainable energy concern both the search for renewable energy sources [3][4][5] and methods for the production of ecological types of energy [6][7][8][9], which differ from traditional types based on hydrocarbon fuel [10][11][12]. The tasks relating to sustainable energy also include the development of technologies for the use of non-renewable energy sources: efficient waste-processing [13][14][15], the construction of nuclear mini-reactors [16], and the creation of energy devices based on the direct conversion of various types of energy into electrical and thermal energy [17][18][19]. A well-known device for directly converting the chemical energy of fuels into electrical energy is a fuel cell [19][20][21]. If the electrolyte in the fuel cell is a ceramic material that is permeable to oxygen ions, it is referred to as a solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) [21][22][23][24][25].

The advantages of SOFCs are the absence of noble metals in their composition and the flexibility of fuel types [24][26][27], while the disadvantages include high operating temperatures, which lead to chemical interactions between the parts of the SOFCs [28][29] and fast degradation [30][31][32]. The high temperatures required to operate SOFCs with conventional electrolytes on the basis of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) lead to the formation of metastable phases, sealing, and thermal and chemical incompatibility with electrode materials [33][34][35].

One of the ways to solve the described problem is to decrease the operating temperature of SOFCs and develop fuel cells operating at medium- [36][37][38] and low-temperature ranges [39][40]. This has resulted in investigations into new classes of electrolytes [41][42][43][44] and the development of SOFCs enhanced with nanostructured materials [45][46]. The utilization of nanotechnologies, energy production and energy storage devices is extremely prospective due to their durability, sustainability, long lifetime, and low cost [47]. Among the alternative electrolytes used in low- and intermediate-temperature SOFCs, complex oxides with an ABO3-type perovskite structure have attracted specific attention due to their high efficiency in energy conversion [48][49][50][51]. For the first time, economical electrolyte materials based on doped lanthanum aluminate LaAlO3 were reported by Fung and Chen in 2011 [52].

It is worth noting that previous generalizing works on lanthanum aluminate were aimed at the synthesis and characterization of LaAlO3 phosphors (published by Kaur et al. in 2013 [53]) and at some properties and applications of LaAlO3 not concerned with SOFCs (observed by Rizwan et al., in 2019) [54]. The studides is dedicated to recent progress in the design, characterization and application of electrolyte materials for SOFCs based on the doped LaAlO3 complex oxides with a perovskite structure. The doped LaGaO3 and LaAlO3 phases constitute a family of oxygen-conducting electrolytes mainly, while other La-based perovskites (LaScO3, LaInO3, LaYO3, LaYbO3) exhibit protonic conductivity as well [49].

2. Synthesis, Structure and Morphology

For the synthesis of doped LaAlO3 oxides, several well-developed techniques are usually used: solid-state reaction technology [55][56][57][58], the mechanochemical route [59], co-precipitation [60][61] and organic-nitrate precursor pyrolysis [62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69].

Employing conventional solid-state reaction technology, LaAlO3 samples can be directly obtained from La2O3 and Al2O3. In [55], these initial reactants were ground down, homogenized in a water media, desiccated and pressed into pellets annealed at a temperature range of 780–1100 °C. Such a temperature regime allows for single-phase LaAlO3 samples to be prepared. A similar technology was used in work [56] to synthesize LaAl1−xZnxO3−δ (here, δ is the oxygen nonstoichiometry; δ = x/2 in the case of oxidation-state stable cations and one charge state difference between the host and impurity cations). As initial reagents, stoichiometric amounts of aluminium and zinc oxides were milled in ethanol. The heat treatment included five 24-h stages at a temperature range of 700–1100 °C. Single-phased LaAlO3 and LaAl0.95Zn0.05O3−δ were obtained at 1250 and 1200 °C, respectively.

Fabian et al. [59] synthesised Ca-doped LaAlO3 powders using the mechanochemical method. Oxide powders of La2O3, γ-Al2O3 and CaO in appropriate proportions were milled in a planetary mill at 600 rpm. The prepared powders were pressed into disks with polyethylene glycol as a plasticizer. The LaAlO3 and La1−xCaxAlO3−δ pellets were sintered at 1700 and 1450 °C, respectively, to achieve a desirable ceramic densification.

LaAlO3 complex oxides were prepared starting from water solutions of aluminium and lanthanum chlorides with a molar ratio for the metal components of 1:1 [60]. Solutions with high and low concentrations of starting reagents were mixed with an ammonium solution serving as a precipitation agent. The obtained gels were filtered, washed with distilled water and dried twice, at 25 °C for 24 h and at 100 °C for 2 h. The prepared powders were calcined at a temperature range of 600–900 °C for 1 h. The powder obtained from the high-concentration solution was annealed at 900 °C for 2 h in air, then ground in a rotary mill with zirconia balls in dry ethanol, pressed and calcined at 1300–1500 °C for 2 h.

The most widely used technology for the preparation of LaAlO3 and its doped derivatives is the pyrolysis of organic-nitrate compositions, known as the sol-gel [62][63][68] or autocombustion methods (or self-propagating high-temperature synthesis, and the Pechini method) [64][65][66][67][69]. Utilizing different fuels during the pyrolysis process coupled with various annealing temperatures affects the crystallinity, powder dispersity, and ceramics density, determining the functional properties of the obtained LaAlO3-based ceramic materials [68][70][71].

LaAlO3 powders were prepared by Zhang et al. [62] from La(NO3)3·6H2O and Al(NO3)3·9H2O: they were dissolved in 2-methoxyethanol and then mixed with citric acid at a molar ratio of 1:1 to the total content of metal ions. The obtained solutions were heated and dried at 80 °C until gelatinous LaAlO3 precursors were obtained, which were then calcined at 600–900 °C for 2 h.

To obtain La0.9Sr0.1Al0.97Mg0.03O3−δ powder, La(NO3)3·6H2O, Al(NO3)3·9H2O, Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, Sr(NO3)2, EDTA, C2H5NO2 and NH3·H2O were used in [63]. The molar ratio of glycine and EDTA to overall metal-ion content was 1.2:1:1; the ratio of NH3·H2O to EDTA was adjusted to 1.15:1. The aqueous solution of metal nitrates was prepared and heated at 80 °C, and then the EDTA-ammonia solution and glycine were added. The colourless solution was dried, and the obtained brown resin was calcined at 350 °C; it was then ground down and calcined at 600–1000 °C for 3 h. The obtained powders were finally pressed into disks followed by sintering at 1600–1700 °C for 5 h.

According to Adak and Pramanik [64], LaAlO3 was prepared from a 10% aqueous polyvinyl alcohol precursor that was added to a solution obtained from La2O3 (99%) dissolved in nitric acid and Al(NO3)3·9H2O. The organic-nitrate mixture was evaporated at 200 °C until dehydration; then, spontaneous decomposition and the formation of a voluminous black fluffy powder occurred. The obtained powders were ground down and annealed at 600–800 °C for 2 h to form a pure phase.

Verma et al. [65] synthesized LaAlO3 and La0.9−xSr0.1BaxAl0.9Mg0.1O3−δ (x = 0.00, 0.01 and 0.03) samples from initial reagents composed of La(NO3)3·H2O, Sr(NO3)2, Ba(NO3)2, Al(NO3)3·6H2O and Mg(NO3)2·6H2O initial reagents. C6H8O7·H2O was used as an organic fuel. The metal nitrates and citric acid were dissolved in distilled water, resulting in the formation of a transparent solution. The pH value required for proper combustion was achieved by the addition of ammonia solution.

The literature shows that the annealing temperature of the precursor powders plays a significant role in complex oxide synthesis: this regulates the density of the final polycrystalline ceramic samples [72]. For practical applications, it is important to obtain LaAlO3-based samples with a narrow distribution of fine-grained particles. These requirements were fulfilled in [60], where a fully converted LaAlO3 phase was formed at relatively low temperatures. In more detail, the researchers developed a co-precipitation technique enabling the formation of single-phase LaAlO3 powders after its calcination in air at 900 °C for 2 h. A narrow particle size distribution for LaAlO3 powder was achieved in [60], where milling in an ethanol medium was conducted.

A Rietveld analysis of the XRD pattern confirmed the presence of a pure perovskite phase with a rhombohedral structure, referring to the R-3c space group. Reference [60] calculated unit cell parameters for the LaAlO3 sample (a = 5.3556(1) Å and c = 13.1518(2) Å) agreed well with results from neutron powder diffraction [73]. The primitive LaAlO3 cell consists of two formula units. The rotation of AlO6 octahedra is caused by changes to the θ angle (Al–O–Al). Above 540 °C, a phase transition from the rhombohedral to cubic structure was observed for LaAlO3 [73]. The cubic lattice of LaAlO3 with a unit cell parameter of a = 3.8106(1) Å corresponds to the Pm3m space group [73].

Concluding the chapter about the synthesis methods of doped LaAlO3 oxides, from the perspective of their use in SOFCs, the co-precipitation method should be noted as the most optimal synthetic method. The co-precipitation method with a subsequent sintering of samples at 900 °C is well-approved and allows for both single-phase powders with a narrow nano-size particle distribution and ceramic samples with high relative densities to be obtained.

3. Functional Properties

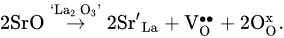

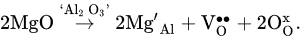

LaAlO3, a basic (undoped) lanthanum aluminate, has very low electrical conductivity, equal to around 1 × 10−6 S cm−1 at 900 °C [69]. La-site doping of LaAlO3 with strontium enhances electrical conductivity because it improves the oxygen vacancy concentration responsible for oxygen-ion transport, [74]. Al-site modification of LaAlO3 with acceptor dopants (for example, magnesium) can also increase the total and ionic conductivities:

The possibility of forming good oxygen-ionic conductivity by doping LaAlO3 oxides has promoted studies on their potential application in SOFCs [52][59][65][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83]. The co-doping strategy is a beneficial way to further increase ionic conductivity [74][75][76][80]; this is due to the fact that, along with the above-mentioned equation, an additional quantity of oxygen vacancies can be formed according to the following mechanism [74]:

According to the results of [52], the simultaneous doping of LaAlO3 with barium and yttrium drastically enhanced ionic transport. For example, the total conductivity of La0.9Ba0.1Al0.9Y0.1O3−δ at 800 °C was close to that of YSZ (2 × 10−2 S cm−1). There are various ways to tailor the transport properties of LaAlO3-based materials. For example, the doping of (La,Sr)AlO3 with manganese resulted in total conductivity rising due to the substitution of Mn3+ ions, which were transformed into Mn2+ and Mn4+ ions at the Al3+ position, enhancing an electronic contribution [69][77]. Therefore, co-doped (La,Sr)(Al,Mn)O3 is attributed to mixed ionic-electronic conductors (MIEC). The Pr-doping of (La,Sr)AlO3 had a positive influence on transport properties due to the suppression of grain boundary resistivity [78], and the isovalent substitution of La3+-ions with Sm3+-ions in (La,Sr)AlO3−δ resulted in the formation of a pronounced mixed ion-electron conduction [81] due to the generation of more electrons than in the case of the aliovalent substitution of La3+ ions with Ba2+ ions.

The electrical conductivity values of LaAlO3-based ceramic materials are summarized in Table 1. Analysis of these data confirms that the simultaneous modification of both sublattices of LaAlO3 results in improved conductivity compared to those reached using single doping approaches. However, it should be noted that the Sr- and Mg- co-doped LaAlO3 materials exhibit mixed ionic-electronic conduction in air atmospheres over a wide temperature range (800–1400 °C), while predominant ionic transport occurs for more reduced atmospheres (for example, wet hydrogen). This is typical behaviour for various La-based perovskites [49] as well as for other perovskite-related ion-conducting electrolytes [84].

Table 1. Total conductivity and activation energy values for LaAlO3 ceramic materials.

| Sample | T (°C) | σ (S cm−1) | Ea (eV) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LaAlO3 | 900 | 6 × 10−4 | 1.30 | [52] |

| LaAlO3 | 700 | 6.7 × 10−4 | 0.99 | [65] |

| LaAlO3 | 900 | 1.1 × 10−6 | 1.83 | [69] |

| LaAlO3 | 900 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 1.88 | [74] |

| LaAlO3 | 800 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 1.30 | [76] |

| La0.9Ca0.1AlO3−δ | 900 | 6.0 × 10−3 | 1.08 | [59] |

| La0.9Sr0.1AlO3−δ | 900 | 1.1 × 10−2 | 1.14 | [74] |

| La0.9Sr0.1AlO3−δ | 800 | 9.0×10−3 | 0.93 | [78] |

| La0.8Sr0.2AlO3−δ | 800 | 6.2 × 10−3 | 1.06 | [69] |

| La0.8Sr0.2AlO3−δ | 900 | 1.5 × 10−2 | 1.06 | [69] |

| La0.8Sr0.2AlO3−δ | 900 | 1.1 × 10−2 | 1.16 | [74] |

| La0.8Sr0.2AlO3−δ | 810 | 4.3 × 10−3 | 1.06 | [77] |

| La0.7Pr0.2Sr0.1AlO3−δ | 800 | 2.3 × 10−2 | 0.84 | [78] |

| LaAl0.95Zn0.05O3−δ | 700 | 8.5 × 10−4 | 1.05 | [56] |

| LaAl0.95Zn0.05O3−δ | 900 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 1.05 | [56] |

| LaAl0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 900 | 9.6 × 10−3 | 1.05 | [74] |

| LaAl0.5Mn0.5O3−δ | 800 | 4.7(2) | 0.22 | [69] |

| LaAl0.5Mn0.5O3−δ | 900 | 5.8(2) | 0.22 | [69] |

| La0.9Sr0.1Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 700 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 1.56 | [65] |

| La0.9Sr0.1Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 700 | 5.3 × 10−4 | 1.38 | [81] |

| La0.9Sr0.1Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 900 | 2.0 × 10−2 | 0.90 | [75] |

| La0.8Sr0.2Al0.95Mg0.05O3−δ | 900 | 1.3 × 10−2 | 1.15 | [74] |

| La0.89Sr0.1Ba0.01Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 700 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 1.48 | [65] |

| La0.89Sr0.1Ba0.01Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ tape | 700 | 6.0 × 10−4 | 0.60 | [79] |

| La0.89Sr0.1Ba0.01Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ pellet | 700 | 4.6 × 10−2 | 0.75 | [79] |

| La0.87Sr0.1Ba0.03Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 700 | 1.7 × 10−3 | 1.38 | [65] |

| La0.8Sr0.2Al0.5Mn0.5O3−δ | 800 | 8.6(3) | 0.15 | [69] |

| La0.8Sr0.2Al0.5Mn0.5O3−δ | 900 | 9.8(2) | 0.15 | [69] |

| La0.8Sr0.2Al0.7Mn0.3O3−δ | 810 | 0.75 | 0.29 | [77] |

| La0.8Sr0.2Al0.5Mn0.5O3−δ | 810 | 10 | 0.17 | [77] |

| (La0.8Sr0.2)0.94Al0.5Mn0.5O3−δ | 810 | 12 | 0.14 | [77] |

| La0.9Ba0.1Al0.9Y0.1O3−δ | 800 | 1.8 × 10−2 | 0.82 | [52] |

| La0.9Ba0.1Al0.9Y0.1O3−δ | 900 | 3.1 × 10−2 | 0.82 | [52] |

| La0.87Sr0.1Sm0.03Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 700 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 1.09 | [81] |

| La0.85Sr0.1Sm0.05Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ | 700 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 1.10 | [81] |

Thermal expansion coefficients (TECs) play an important role in material selection when seeking to avoid thermal incompatibilities between various parts of SOFCs. According to da Silva and de Miranda [69], the average TEC values for LaAlO3 and La0.8Sr0.2AlO3 were equal to around 11.4 × 10−6 and 9.9 × 10−6 K−1, respectively. These data confirm that the TEC values of LaAlO3-based materials were close to those of the conventional YSZ electrolyte, i.e., 10.9 × 10−6 K−1 [85].

The chemical compatibility of La0.9Sr0.1Al0.97Mg0.03O3−δ as an electrolyte material with NiO-Ce0.9Gd0.1O2−δ(GDC), Sr0.88Y0.08TiO3−δ and La0.75Sr0.25Cr0.5Mn0.5O3−δ as anode SOFC materials was thoroughly investigated in [80] using XRD analysis and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. The obtained results demonstrated that Sr0.88Y0.08TiO3−δ and La0.75Sr0.25Cr0.5Mn0.5O3−δ interacted with La0.9Sr0.1Al0.97Mg0.03O3−δ due to the interdiffusion of Sr2+, Ti4+, Mn3+ and Cr3+ cations into the La0.9Sr0.1Al0.97Mg0.03O3−δ lattice. An interaction between La0.9Sr0.1Al0.97Mg0.03O3−δ and NiO-GDC at 1300 °C was not detected, which means that joint utilization is possible.

The XRD patterns of two mixtures, La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.85Mg0.15O3−δ/La0.9Sr0.1AlO3−δ and NiO/La0.9Sr0.1AlO3−δ (annealed at 1450 °C), confirmed that there were no chemical interactions between these components [86]. The researchers noted that doped LaAlO3 materials can serve as additives to the composite electrolytes and the anode-protective layers [86]. In addition, Mn-doped LaAlO3 phases are considered a constituent part of the composite electrolytes, providing for the effective electrochemical oxidation of methane via ethylene and ethane [87].

4. Applications in SOFCs

There are fragmentary data on the application of lanthanum aluminate electrolytes in SOFCs.

An SOFC was fabricated with 70% NiO–30% YSZ as an anode, a samarium doped ceria (SDC) as an interlayer, La0.9Ba0.1Al0.9Y0.1O3−δ (LBAYO) as an electrolyte and lanthanum strontium manganite (LSM) as a cathode, and tested in [52]. LBAYO films with thicknesses of 63 and 74 μm were electrophoretically deposited on the LSM pellets with a diameter of 25 mm and a thickness of 2 mm. The LSM substrates and the deposited LBAYO films were then annealed at 1450 °C for 2 h to achieve full electrolyte densification. A NiO-YSZ anode with a thickness of 40 μm was screen-printed on the LBAYO/LSM sample and then sintered at 1500 °C for 6 h. To avoid chemical interactions between the NiO and the LBAYO film, an SDC buffer layer with a thickness of 10 μm was additionally screen-printed on the LBAYO film between the electrolyte and the anode. Humidified hydrogen was used as a fuel, while air was used as an oxidant. The open-circuit voltage (OCV) values of the fabricated cells were 0.927 and 0.953 V, while the maximum power density values were 0.306 and 0.235 W cm−2 for the LBAYO electrolyte layers with thicknesses of 63 and 74 μm, respectively. The long-term stability experiments demonstrated negligible degradation of the SOFC with LBAYO electrolyte over 10 days.

Another Ni-GDC/GDC/La0.9Sr0.1Al0.97Mg0.03O3−δ/GDC/La0.75Sr0.25FeO3−δ electrolyte-supported cell was tested in [80]. For this single cell with a La0.9Sr0.1Al0.97Mg0.03O3−δ electrolyte thickness of 550 μm, the OCV and Pmax values at 800 °C were found to be equal to 0.925 V and 0.195 W cm−2, respectively.

5. Conclusions

Concluding about the applications of doped LaAlO3 oxides as electrolyte materials in SOFCs, it is worth noting that: on the one side, the power characteristics of SOFCs with doped LaAlO3 electrolytes are approximately equal to the Pmax values of SOFCs with Sr, Mg-doped LaGaO3 electrolytes without buffer layers [51]; on the another side, the commercial production of the LaAlO3-based electrolytes is significantly cheaper than yhe production of the LaGaO3-based electrolytes. That is why, further investigations of the LaAlO3-based electrolytes would be continued.

References

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Rygg, B.J. A review of dominant sustainable energy narratives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110955.

- Chu, W.; Calise, F.; Duić, N.; Østergaard, P.A.; Vicidomini, M.; Wang, Q. Recent advances in technology, strategy and application of sustainable energy systems. Energies 2020, 13, 5229.

- Østergaard, P.A.; Duic, N.; Noorollahi, Y.; Mikulcic, H.; Kalogirou, S. Sustainable development using renewable energy technology. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2430–2437.

- Kolosok, S.; Bilan, Y.; Vasylieva, T.; Wojciechowski, A.; Morawski, M. A scoping review of renewable energy, sustainability and the environment. Energies 2021, 14, 4490.

- Erixno, O.; Rahim, N.A.; Ramadhani, F.; Adzman, N.N. Energy management of renewable energy-based combined heat and power systems: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 51, 101944.

- Martínez, M.L.; Vázquez, G.; Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Silva, R.; Moreno-Casasola, P.; Mendoza-González, G.; López-Portillo, J.; MacGregor-Fors, I.; Heckel, G.; Hernández-Santana, J.R.; et al. A systemic view of potential environmental impacts of ocean energy production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111332.

- Pradhan, S.; Chakraborty, R.; Mandal, D.K.; Barman, A.; Bose, P. Design and performance analysis of solar chimney power plant (SCPP): A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101411.

- Nazir, M.S.; Ali, N.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Potential environmental impacts of wind energy development: A global perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health. 2020, 13, 85–90.

- Soltani, M.; Moradi Kashkooli, F.; Souri, M.; Rafiei, B.; Jabarifar, M.; Gharali, K.; Nathwani, J.S. Environmental, economic, and social impacts of geothermal energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110750.

- Yuan, X.; Su, C.-W.; Umar, M.; Shao, X.; Lobont, O.-R. The race to zero emissions: Can renewable energy be the path to carbon neutrality? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114648.

- Tomkins, P.; Müller, T.E. Evaluating the carbon inventory, carbon fluxes and carbon cycles for a long-term sustainable world. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3994–4013.

- Nurdiawati, A.; Urban, F. Towards deep decarbonisation of energy-intensive industries: A review of current status, technologies and policies. Energies 2021, 14, 2408.

- Bolatkhan, K.; Kossalbayev, B.D.; Zayadan, B.K.; Tomo, T.; Veziroglu, T.N.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Hydrogen production from phototrophic microorganisms: Reality and perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 5799–5811.

- Barba, F.J.; Gavahian, M.; Es, I.; Zhu, Z.; Chemat, F.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Solar radiation as a prospective energy source for green and economic processes in the food industry: From waste biomass valorization to dehydration, cooking, and baking. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1121–1130.

- Wijayasekera, S.C.; Hewage, K.; Siddiqui, O.; Hettiaratchi, P.; Sadiq, R. Waste-to-hydrogen technologies: A critical review of techno-economic and socio-environmental sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 5842–5870.

- Testoni, R.; Bersano, A.; Segantin, S. Review of nuclear microreactors: Status, potentialities and challenges. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 138, 103822.

- Timmer, M.A.G.; De Blok, K.; Van Der Meer, T.H. Review on the conversion of thermoacoustic power into electricity. J. Acoustic. Soc. Am. 2018, 143, 841–857.

- Selvan, K.V.; Hasan, M.N.; Mohamed Ali, M.S. Methodological reviews and analyses on the emerging research trends and progresses of thermoelectric generators. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 113–140.

- Cigolotti, V.; Genovese, M.; Fragiacomo, P. Comprehensive review on fuel cell technology for stationary applications as sustainable and efficient poly-generation energy systems. Energies 2021, 14, 4963.

- Mishra, P.; Saravanan, P.; Packirisamy, G.; Jang, M.; Wang, C. A subtle review on the challenges of photocatalytic fuel cell for sustainable power production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 22877–22906.

- Minh, N.Q. Solid oxide fuel cell technology-features and applications. Solid State Ion. 2004, 174, 271–277.

- Bilal Hanif, M.; Motola, M.; Qayyum, S.; Rauf, S.; Khalid, A.; Li, C.-J.; Li, C.-X. Recent advancements, doping strategies and the future perspective of perovskite-based solid oxide fuel cells for energy conversion. Chem. Engin. J. 2022, 428, 132603.

- Peng, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, X.-L.; Xu, Y.-W.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) performance evaluation, fault diagnosis and health control: A review. J. Power Sources 2021, 505, 230058.

- Zarabi Golkhatmi, S.; Asghar, M.I.; Lund, P.D. A review on solid oxide fuel cell durability: Latest progress, mechanisms, and study tools. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112339.

- Jacobson, A.J. Materials for solid oxide fuel cells. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 660–674.

- Saadabadi, S.A.; Thallam Thattai, A.; Fan, L.; Lindeboom, R.E.F.; Spanjers, H.; Aravind, P.V. Solid oxide fuel cells fuelled with biogas: Potential and constraints. Renew. Energy 2019, 134, 194–214.

- Yang, B.C.; Koo, J.; Shin, J.W.; Go, D.; Shim, J.H.; An, J. Direct alcohol-fueled low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells: A review. Energy Technol. 2019, 7, 5–19.

- Zhang, L.; Chen, G.; Dai, R.; Lv, X.; Yang, D.; Geng, S. A review of the chemical compatibility between oxide electrodes and electrolytes in solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2021, 492, 229630.

- Brandon, N.P.; Skinner, S.; Steele, B.C.H. Recent advances in materials for fuel cells. Ann. Rev. Mater. Res. 2003, 33, 182–213.

- Zhou, Z.; Nadimpalli, V.K.; Pedersen, D.B.; Esposito, V. Degradation mechanisms of metal-supported solid oxide cells and countermeasures: A review. Materials 2021, 14, 3139.

- Sreedhar, I.; Agarwal, B.; Goyal, P.; Agarwal, A. An overview of degradation in solid oxide fuel cells-potential clean power sources. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 1239–1270.

- Yang, Z.; Guo, M.; Wang, N.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Han, M. A short review of cathode poisoning and corrosion in solid oxide fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 24948–24959.

- Zakaria, Z.; Abu Hassan, S.H.; Shaari, N.; Yahaya, A.Z.; Boon Kar, Y. A review on recent status and challenges of yttria stabilized zirconia modification to lowering the temperature of solid oxide fuel cells operation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 631–650.

- Hanif, M.B.; Rauf, S.; Motola, M.; Babar, Z.U.D.; Li, C.-J.; Li, C.-X. Recent progress of perovskite-based electrolyte materials for solid oxide fuel cells and performance optimizing strategies for energy storage applications. Mat. Res. Bull. 2022, 146, 111612.

- Atkinson, A.; Sun, B. Residual stress and thermal cycling of planar solid oxide fuel cells. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2007, 23, 1135–1143.

- Brett, D.J.L.; Atkinson, A.; Brandon, N.P.; Skinner, S.J. Intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1568–1578.

- Tarancón, A. Strategies for lowering solid oxide fuel cells operating temperature. Energies 2009, 2, 1130–1150.

- Kilner, J.A.; Burriel, M. Materials for intermediate-temperature solid-oxide fuel cells. Ann. Rev. Mater. Res. 2014, 44, 365–393.

- Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Asghar, M.I.; Lund, P.D. Low temperature ceramic fuel cells employing lithium compounds: A review. J. Power Sources 2021, 503, 230070.

- Su, H.; Hu, Y.H. Progress in low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells with hydrocarbon fuels. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 402, 126235.

- Kharton, V.V.; Marques, F.M.B.; Atkinson, A. Transport properties of solid oxide electrolyte ceramics: A brief review. Solid State Ion. 2004, 174, 135–149.

- Mahato, N.; Banerjee, A.; Gupta, A.; Omar, S.; Balani, K. Progress in material selection for solid oxide fuel cell technology: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 72, 141–331.

- Wang, F.; Lyu, Y.; Chu, D.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D. The electrolyte materials for SOFCs of low-intermediate temperature: Review. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1551–1562.

- Shi, H.; Su, C.; Ran, R.; Cao, J.; Shao, Z. Electrolyte materials for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2020, 30, 764–774.

- Abdalla, A.M.; Hossain, S.; Azad, A.T.; Petra, P.M.I.; Begum, F.; Eriksson, S.G.; Azad, A.K. Nanomaterials for solid oxide fuel cells: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 353–368.

- Fan, L.; Zhu, B.; Su, P.-C.; He, C. Nanomaterials and technologies for low temperature solid oxide fuel cells: Recent advances, challenges and opportunities. Nano Energy 2018, 45, 148–176.

- Ellingsen, L.A.W.; Hung, C.R.; Bettez, G.M.; Singh, B.; Chen, Z.; Whittingham, M.S.; Strømman, A.H. Nanotechnology for environmentally sustainable electromobility. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 1039–1051.

- Zhigachev, A.O.; Rodaev, V.V.; Zhigacheva, D.V.; Lyskov, N.V.; Shchukina, M.A. Doping of scandia-stabilized zirconia electrolytes for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell: A review. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 32490–32504.

- Kasyanova, A.V.; Rudenko, A.O.; Lyagaeva, Y.G.; Medvedev, D.A. Lanthanum-containing proton-conducting electrolytes with perovskite structures. Membr. Membr. Technol. 2021, 3, 73–97.

- Artini, C. Crystal chemistry, stability and properties of interlanthanide perovskites: A review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 37, 427–440.

- Ishihara, T.; Matsuda, H.; Takita, Y. Doped LaGaO3 perovskite type oxide as a new oxide ionic conductor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 3801–3803.

- Feng, M.; Goodenough, J.B.; Huang, K.; Milliken, C. Fuel cells with doped lanthanum gallate electrolyte. J. Power Sources 1996, 63, 47–51.

- Fung, K.Z.; Chen, T.Y. Cathode-supported SOFC using a highly conductive lanthanum aluminate-based electrolyte. Solid State Ion. 2011, 188, 64–68.

- Kaur, J.; Singh, D.; Dubey, V.; Suryanarayana, N.S.; Parganiha, Y.; Jha, P. Review of the synthesis, characterization, and properties of LaAlO3 phosphors. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 40, 2737–2771.

- Rizwan, M.; Gul, S.; Iqbal, T.; Mushtaq, U.; Farooq, M.H.; Farman, M.; Bibi, R.; Ijaz, M. A review on perovskite lanthanum aluminate (LaAlO3), its properties and applications. Mat. Res. Express 2019, 6, 112001.

- Popova, V.F.; Tugova, E.A.; Zvereva, I.A.; Gusarov, V.V. Phase equilibria in the LaAlO3-LaSrAlO4 system. Glass Phys. Chem. 2004, 30, 564–567.

- Egorova, A.V.; Belova, K.G.; Animitsa, I.E.; Morkhova, Y.A.; Kabanov, A.A. Effect of zinc doping on electrical properties of LaAlO3 perovskite. Chim. Technol. Acta 2021, 8, 20218103.

- Azaiz, A.; Kadari, A.; Alves, N.; Faria, L.O. Influence of carbon doping on the thermoluminescence properties of LaAlO3 crystal grown by solid state reaction method. Int. J. Microstruct. Mater. Prop. 2020, 15, 156–167.

- Beheshti, M.; Malekfar, R. A novel approach for the synthesis of lanthanum aluminate nanoparticles using thermal shock assisted solid-state method as a microwave absorber layer. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 270, 124848.

- Fabián, M.; Arias-Serrano, B.I.; Yaremchenko, A.A.; Kolev, H.; Kaňuchová, M.; Briančin, J. Ionic and electronic transport in calcium-substituted LaAlO3 perovskites prepared via mechanochemical route. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 5298–5308.

- Brylewski, T.; Bućko, M.M. Low-temperature synthesis of lanthanum monoaluminate powders using the co-precipitation–calcination technique. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 5667–5674.

- Jin, X.; Zhang, L.; Luo, H.; Fan, X.; Jin, L.; Liu, B.; Li, D.; Qiu, Z.; Gan, Y. Preparation of Eu3+ doped LaAlO3 phosphors by coprecipitation-molten salt synthesis. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2018, 188, 1–11.

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, T.; Qi, X.W.; Qi, J.Q.; Sun, G.F.; Chen, H.H.; Zhong, R.X. Preparation and characterization of LaAlO3 via sol-gel process. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 624, 26–29.

- Qin, G.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; He, Z. Synthesis of Sr and Mg double-doped LaAlO3 nanopowders via EDTA-glycine combined process. Powder Technol. 2013, 235, 880–885.

- Adak, A.K.; Pramanik, P. Synthesis and characterization of lanthanum aluminate powder at relatively low temperature. Mater. Lett. 1997, 30, 269–273.

- Verma, O.N.; Singh, S.; Singh, V.K.; Najim, M.; Pandey, R.; Singh, P. Influence of Ba doping on the electrical behaviour of La0.9Sr0.1Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ system for a solid electrolyte. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 1010–1021.

- Rivera-Montalvo, T.; Morales-Hernandez, A.; Barrera-Angeles, A.A.; Alvarez-Romero, R.; Falcony, C.; Zarate-Medina, J. Modified Pechini’s method to prepare LaAlO3:RE thermoluminescent. Mater. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2017, 140, 68–73.

- Garcia, A.B.S.; Bispo-Jr, A.G.; Lima, S.A.M.; Pires, A.M. Effects of the Pechini’s modified synthetic route on structural and photophysical properties of Eu3+ or Tb3+-doped LaAlO3. Mat. Res. Bull. 2021, 143, 111462.

- Silveira, I.S.; Ferreira, N.S.; Souza, D.N. Structural, morphological and vibrational properties of LaAlO3 nanocrystals produced by four different methods. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 27748–27758.

- da Silva, C.A.; de Miranda, P.E.V. Synthesis of LaAlO3 based materials for potential use as methane-fueled solid oxide fuel cell anodes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 10002–10015.

- Lee, G.; Kim, I.; Yang, I.; Ha, J.-M.; Na, H.B.; Jung, J.C. Effects of the preparation method on the crystallinity and catalytic activity of LaAlO3 perovskites for oxidative coupling of methane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 429, 55–61.

- Stathopoulos, V.N.; Kuznetsova, T.; Lapina, O.; Khabibulin, D.; Pandis, P.K.; Krieger, T.; Chesalov, Y.; Gulyalev, R.; Krivensov, V.; Larina, T.; et al. Evolution of bulk and surface structures in stoichiometric LaAlO3 mixed oxide prepared by using starch as template. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 207, 423–434.

- Lessing, P.A. Mixed-cation oxide powders via polymeric precursors. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 1989, 68, 1002–1007.

- Howard, C.J.; Kennedy, B.J.; Chakoumakos, B.C. Neutron powder diffraction study of rhombohedral rare-earth aluminates and the rhombohedral to cubic phase transition. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2000, 12, 349–365.

- Nguyen, T.L.; Dokiya, M.; Wang, S.; Tagawa, H.; Hashimoto, T. The effect of oxygen vacancy on the oxide ion mobility in LaAlO3-based oxides. Solid State Ion. 2000, 130, 229–241.

- Park, J.Y.; Choi, G.M. Electrical conductivity of Sr and Mg doped LaAlO3. Solid State Ion. 2002, 154–155, 535–540.

- Chen, T.Y.; Fung, K.Z. Comparison of dissolution behavior and ionic conduction between Sr and/or Mg doped LaGaO3 and LaAlO3. J. Power Sources 2004, 132, 1–10.

- Fu, Q.X.; Tietz, F.; Lersch, P.; Stöver, D. Evaluation of Sr- and Mn-substituted LaAlO3 as potential SOFC anode materials. Solid State Ion. 2006, 177, 1059–1069.

- Villas-Boas, L.A.; De Souza, D.P.F. The effect of Pr co-doping on the densification and electrical properties of Sr-LaAlO3. Mater. Res. 2013, 16, 982–989.

- Verma, O.N.; Jha, P.A.; Melkeri, A.; Singh, P. A comparative study of aqueous tape and pellet of (La0.89Ba0.01)Sr0.1Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ electrolyte material. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2017, 521, 230–238.

- Guo-Heng, Q.; Xiao-Wei, H.; Zh, H.U. Chemical compatibility and electrochemical performance between LaAlO3-based electrolyte and selected anode materials. Wuli Huaxue Xuebao/Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2013, 29, 311–318.

- Verma, O.N.; Jha, P.A.; Singh, P.; Jha, P.K.; Singh, P. Influence of iso-valent “Sm” double substitution on the ionic conductivity of La0.9Sr0.1Al0.9Mg0.1O3−δ ceramic system. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 241, 122345.

- Villas-Boas, L.A.; Goulart, C.A.; De Souza, D.P.F. Desenvolvimento microestrutural e mobilidade de ions oxigênio em perovskitas do tipo LaAlO3 dopadas com Sr, Ba e Ca. Rev. Mater. 2020, 25, e-12801.

- Villas-Boas, L.A.; Goulart, C.A.; De Souza, D.P.F. Effects of Sr and Mn co-doping on microstructural evolution and electrical properties of LaAlO3. Process. Appl. Ceram. 2019, 13, 333–341.

- Zvonareva, I.; Fu, X.-Z.; Medvedev, D.; Shao, Z. Electrochemistry and energy conversion features of protonic ceramic cells with mixed ionic-electronic electrolytes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 439–465.

- Tietz, F. Thermal expansion of SOFC materials. Ionics 1999, 5, 129–139.

- Nguyen, T.L.; Dokiya, M. Electrical conductivity, thermal expansion and reaction of (La, Sr)(Ga, Mg)O3 and (La, Sr)AlO3 system. Solid State Ion. 2000, 132, 217–226.

- Venâncio, S.A.; de Miranda, P.E.V. Direct utilization of carbonaceous fuels in multifunctional SOFC anodes for the electrosynthesis of chemicals or the generation of electricity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 13927–13938.

More

Information

Subjects:

Materials Science, Ceramics

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No