Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shuo Qie | -- | 1870 | 2022-06-14 08:57:12 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 1870 | 2022-06-14 10:21:37 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 1870 | 2022-06-14 10:21:53 | | | | |

| 4 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 1870 | 2022-06-16 08:00:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Qie, S. Fbxo4. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23999 (accessed on 10 March 2026).

Qie S. Fbxo4. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23999. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Qie, Shuo. "Fbxo4" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23999 (accessed March 10, 2026).

Qie, S. (2022, June 14). Fbxo4. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23999

Qie, Shuo. "Fbxo4." Encyclopedia. Web. 14 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Fbxo4, also known as Fbx4, belongs to the F-box protein family with a conserved F-box domain. Fbxo4 can form a complex with S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 and Cullin1 to perform its biological functions.

Fbxo4

Cyclin D1

Fxr1

Cell cycle

DNA damage response

Tumor metabolism

Cellular senescence

Apoptosis

EMT

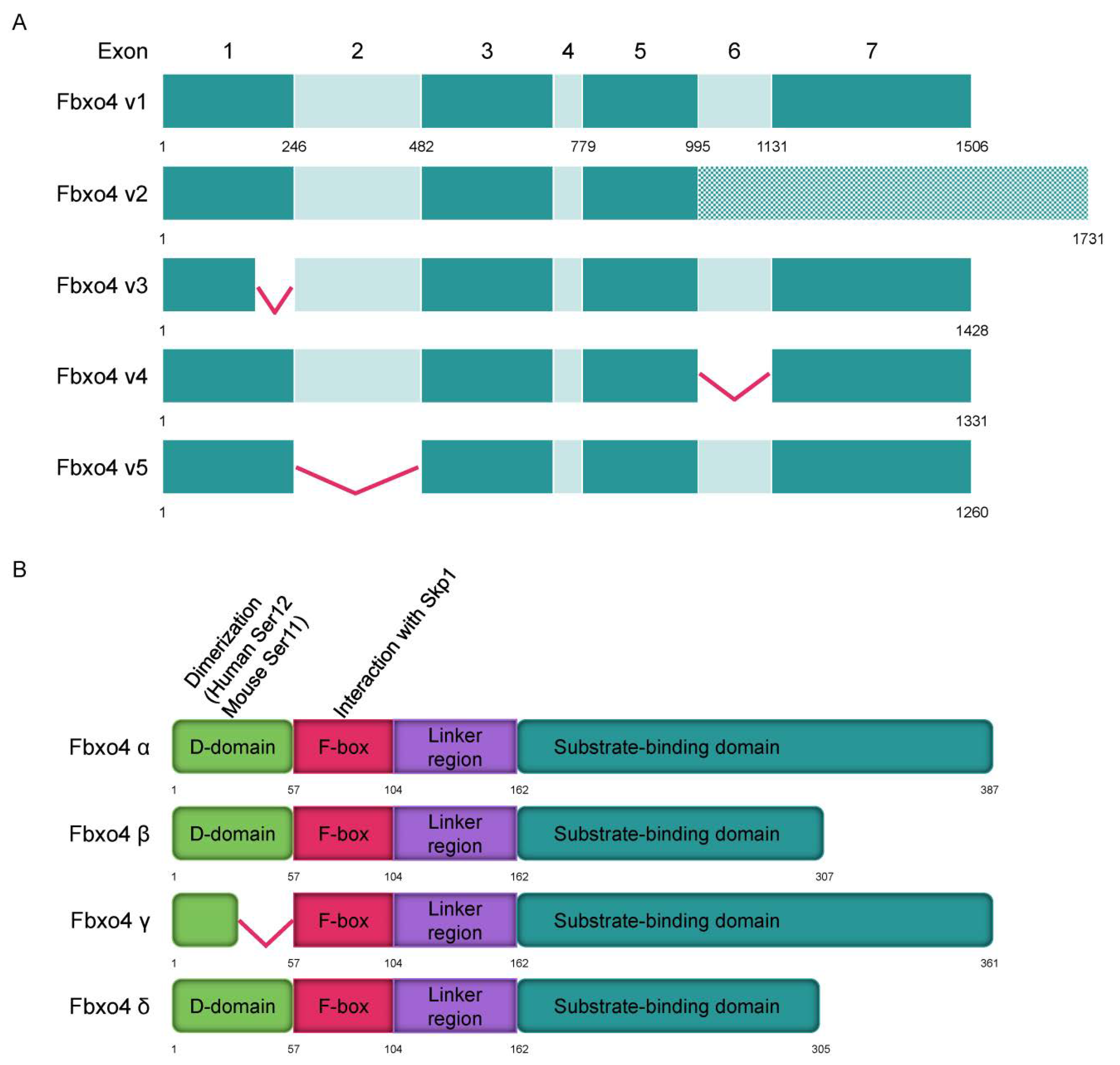

1. The FBXO4 Gene and Protein Structure

FBPs have different isoforms that perform various biological functions [1][2][3]. Consistently, different Fbxo4 isoforms have also been elucidated by analyzing normal human liver/esophagus tissues and their relevant tumor cells (Figure 1A) [4]. In general, tumor cells have less wild type FBXO4 variant 1 compared to that in normal tissues. For example, gastric cancer cells mainly express variants 3 and 4 but not variant 1. The hepatocellular carcinoma tissues express more FBXO4 variants relative to that in normal counterparts. According to the transcriptional variants, Fbxo4 has four different protein isoforms including α, β, γ, and δ (Figure 1B). At the subcellular level, α isoform is mainly expressed in cytoplasm, while β, γ, and δ isoforms are generally located both in cytoplasm and nucleus [4]. Biologically, Fbxo4 isoforms perform different functions. For example, the ectopic expression of α isoform efficiently suppresses colony formation while β, γ, and δ isoforms not only promote colony formation in soft agar, but also enhance the migration of tumor cells.

Figure 1. The transcript variants of FBXO4 and protein structure of different isoforms. (A) Five transcript variants of FBXO4 are shown in schematic plots. (B) Four different isoforms of Fbxo4 are identified with four domains: D domain for dimerization, F-box domain for forming SCF complex, Linker region, and substrate binding domain.

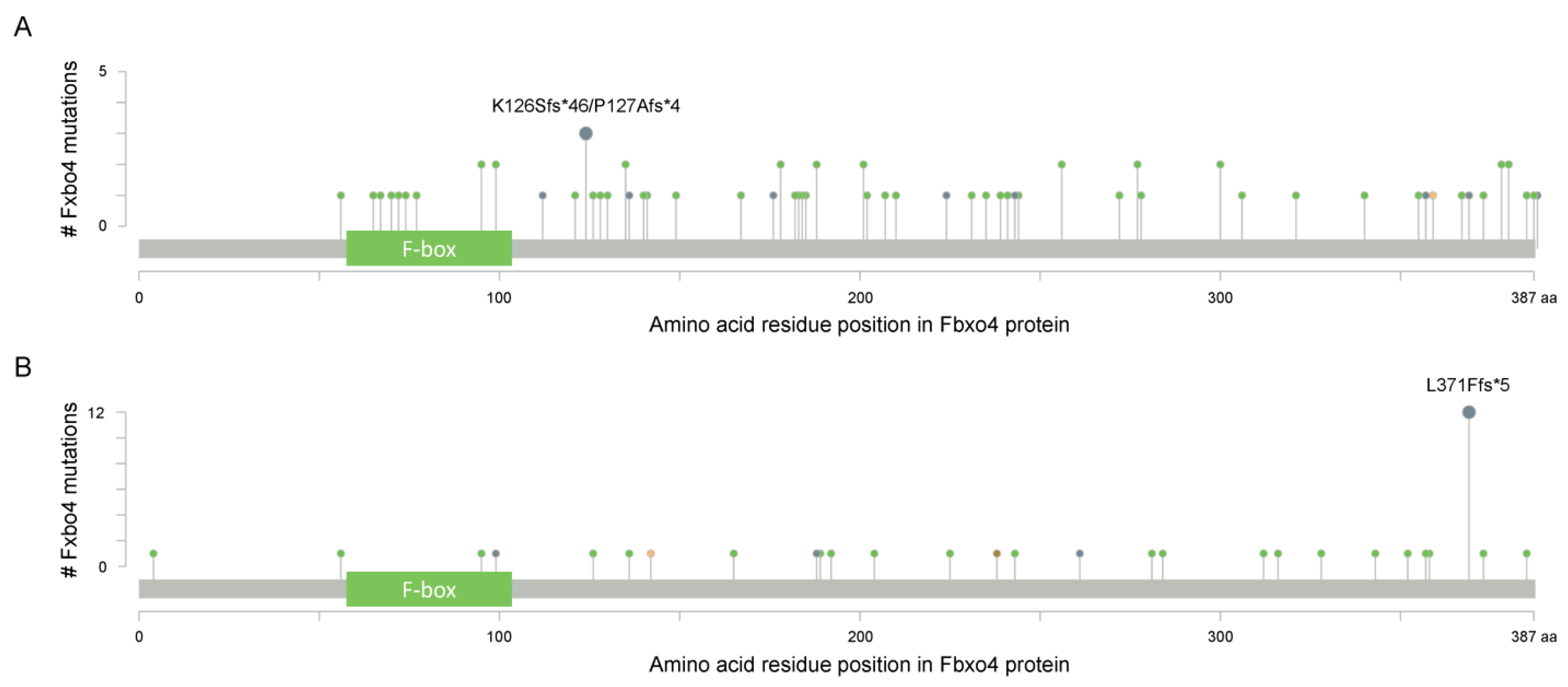

As shown in Figure 1B, Fbxo4 molecule has four domains from N- to C-terminus: D domain for dimerization, F-box domain for the formation of SCF complex, Linker region and substrate binding domain [5]. Structural analyses combined with biophysical and biochemical techniques revealed the full-length Fbxo4 is deficient in E3 ubiquitin ligase activity when in monomeric state. The connecting loop between linker region and substrate binding domain is indispensable for dimerization. Additionally, the N-terminal domain can interact with Cul1-Rbx1 besides functioning for dimerization [6]. The screening of human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissues identified the existence of Fbxo4 mutations, such as S8R, S12L, P13S, L23Q, and G30N in D domain, and P76T mutation in F-box domain, leading to loss of function of Fbxo4 [7]. In addition, other mutations in the FBXO4 gene have also been discovered in tumor tissues from the TCGA PanCancer Atlas Studies (Figure 2A), and in cells from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (Broad, 2019) on the cBioportal website (Figure 2B) [8][9]. In accordance, there are consistent mutations when comparing these bioinformatic findings from previous studies [7]. For example, the mutations located in the F-box domain can compromise the formation of SCF complex.

Figure 2. The cBioportal analysis reveals the existence of FBXO4 mutations (www.cbioportal.org (accessed on 12 April 2022)). (A) The identified mutations of FBXO4 in tumor tissues from the TCGA PanCancer Atlas Studies; all PanCancer related tumors are included for this analysis; there are 10,967 samples in total. (B) The identified mutations of FBXO4 in cells from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (Broad, 2019); all cells in Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (Broad, 2019) are utilized for this analysis. x-axis indicates the amino acid residue position of Fbxo4 protein while y-axis indicates the number of mutations for each highlighted residues.

2. The Regulation of Fbxo4 Expression and Activity

As an E3 ubiquitin ligase, Fbxo4 is not simply regulated at the transcriptional level, but also by comprehensive and multi-dimensional mechanisms, e.g., expression by translational regulation, and activation by co-factor and post-translational modification.

2.1. Translational Regulation of Fbxo4

The regulation of Fbxo4 by Fxr1 is unexpectedly identified when genetically manipulating Fxr1 in mammalian cells [10]. Fbxo4 protein goes up without a corresponding increase of FBXO4 mRNA in cells upon Fxr1 knockdown, and vice versa. Further analyses identified Fxr1 can interact with Fbxo4 mRNA via the AU-rich elements in its 3′ untranslated region [11][12], leading to reduced translation of Fbxo4. These findings suggest that the amplification of FXR1 gene could be the initial hit for its overexpression, which is further enhanced by reducing the expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Fbxo4.

2.2. αB-Crystallin Functions as a Co-Factor of Fbxo4

αB-crystallin, also termed as heat shock protein (Hsp) B5, belongs to small Hsp family that plays critical roles in protein homeostasis, for example, promoting protein folding and maintaining normal cellular functions [13]. Under stress conditions, αB-crystallin can bind to unfolded proteins, prevent their aggregation via its chaperone-like activities, and finally enhancing cellular ability to resist various stresses [14]. The yeast two-hybrid screening analysis identified αB-crystallin can interact with Fbxo4 depending on the phosphorylation of αB-crystallin at Serine (Ser)-19 and Ser-45. Moreover, the aggregation inducing αB-crystallin mutant, R102G, also facilitates its binding to Fbxo4 [15][16]. Biologically, the association of Fbxo4 with αB-crystallin enhances the ubiquitylation of detergent-insoluble proteins. Particularly, the phospho-mimic mutant αB-crystallin can recruit Fbxo4 to the SC35 speckles, highlighting their potentials to ubiquitylate the components of SC35 speckles [15]. Mass spectrometry analysis identified αB-crystallin is enriched in cyclin D1 immunoprecipitates [17]. Biochemical analysis further revealed the formation of αB-crystallin, Fbxo4, and cyclin D1 complex. Fbxo4 can trigger the ubiquitylation of cyclin D1, and enhance its turnover; importantly, genetic manipulation of αB-crystallin is sufficient to alter cyclin D1 expression in mammalian cells [5][18][19]. p53 is another example that requires αB-crystallin for Fbox4-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation [20]. While this does not mean that αB-crystallin is always indispensable for Fbxo4 to perform its E3 ubiquitin ligase activities, for example, there is no direct evidence that αB-crystallin is required for Fbxo4-mediated ubiquitylation of Trf1, Fxr1, Mcl-1, ICAM-1, and PPARγ.

2.3. Phosphorylation and Dimerization of Fbox4

A plethora of studies revealed the majority of FBPs have to form dimers to perform their biological functions. Consistently, Fbxo4 is in the same condition when regarding to this point [7]. Biochemical analyses found the existence of N-terminal dimerization domain in Fbxo4 that regulates its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Mutational analyses revealed that Fbxo4 can be phosphorylated by Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) at Ser-12 in human cells or Ser-11 in mouse cells [7]. The phosphorylation of those Ser residues provides a docking site for 14-3-3ε that facilitates the homodimerization and activation of Fbxo4 (Figure 2B and Figure 3A,B) [21].

3. The Biological Functions of Fbxo4

3.1. Cell Cycle

As an E3 ubiquitin ligase of cyclin D1, Fbxo4 regulates cell cycle progression in both normal and tumor cells [7]. Knockdown of Fbxo4 drives an obvious accelerated entry from G1 into S phase because the accumulation of cyclin D1 in cells with defective Fbxo4 functions [22]. In accordance, loss of Fbxo4 efficiently promotes cell proliferation as well as cellular transformation upon the induction of RasV12 [23]. Not surprisingly, the observations from transgenic mice also confirm the tumor suppressor activities of Fbxo4. The transgenic mice with Fbxo4−/− or Fbxo4−/+ genotypes can spontaneously develop various pathological conditions, including lymphoblastic lymphoma, extramedullary hematopoiesis/intense myeloid proliferation, hemangioma/angioinvasive tumor, dendritic cell tumor, histiocytic sarcoma, early myeloid tumor, mammary carcinoma, and uterine tumor [23]. In addition, loss of Fbxo4 enhances the development of aggressive melanoma in a BrafV600E/+ mouse model [24]. Furthermore, Fbxo4 loss also facilitates the development of esophageal and forestomach papilloma-induced by N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine in transgenic mice that can be therapeutically treated by CDK4/6 inhibitor, palbociclib, suggesting that Fbxo4 can be considered as a marker to assess patients’ response [25].

3.2. DNA Damage Response

Fbxo4 controls DNA damage response because of inappropriate expression of cyclin D1 and Trf1 upon genomic damages. The ectopic expression of a constitutively nuclear mutant of cyclin D1 stabilizes the DNA replication licensing factor, Chromatin Licensing and DNA Replication Factor 1 (Cdt1) [26][27]. The dysregulation of Cdt1 promotes DNA re-replication and DNA damage, leading to chromatid breaks that favor the occurrence of second hit and latterly tumor development. Consistently, defective Fbxo4 activation also accumulates cyclin D1 in the nucleus and enhances the dysregulation of Cdt1 [26]. As a member of the Never in Mitosis Gene A kinase family, NIMA Related Kinase 7 (NEK7) functions as a regulator of telomere integrity. Upon DNA damage, Nek7 is recruited to telomeres to phosphorylate Trf1 at Ser-114 that compromises the interaction between Trf1 and Fbxo4, reducing the ubiquitylation and degradation of Trf1 to alleviate the DNA damage response and to maintain telomere integrity [28].

3.3. Tumor Metabolism

As a critical nutrient for highly proliferating tumor cells, glutamine can be utilized as an energetic, biosynthetic, or reductive precursor [29][30][31]. Glutamine-addiction defines the phenomenon wherein cells depend on glutamine for survival and proliferation. Generally, these cells demonstrate elevated glutaminase 1 (GLS1) expression and glutamine uptake [32]. GLS1 is upregulated in a variety of human tumors, and increased expression or elevated enzymatic activity of GLS1 is significantly associated with poor prognosis, indicating GLS1 is a point of interest for developing targeted therapies [33]. Previous studies revealed dysregulation of Fbxo4-cyclin D1 signaling results in defective mitochondrial function and reduced energy production. Particularly, loss of Fbxo4 promotes the dependency of normal cells and ESCC cells on glutamine. Therefore, combined treatment with CB-839/telaglenastat (GLS1 inhibitor) plus metformin can effectively suppress ESCC cell proliferation in vitro and xenograft growth in vivo [34]. Palbociclib-resistant ESCC cells demonstrate GLS1 upregulation is in a c-Myc-independent manner, making them hyper-glutamine-addicted and more sensitive to combined treatment than their parental counterparts. These findings provide a novel second-line therapy to overcome acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors.

3.4. Cellular Senescence

Cellular senescence defines the arrest of cell proliferation of diploid cells as a result of telomere shortening [35]. Morphologically, senescent cells become enlarged and flattened with the accumulation of lysosomes and mitochondria [36]. The replicative stress enhances DNA damage response that activates the transcription of TP53 and the induction of p21Cip1. Additionally, telomere shortening promotes the expression of p16Ink4a [37]. Both p21Cip1 and p16Ink4a can cause cell cycle arrest at the G1-S phase. Normally, senescent cells are characterized by the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) that refers to the secretion of a group of growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines. As an RNA-binding protein, Fxr1 can bind to p21Cip1 mRNA through the G-quadruplex structure in its 3′ untranslated region and promote the degradation of p21Cip1 mRNA. Therefore, silencing of Fxr1 leads to the accumulation of p21Cip1, and finally cellular senescence [38]. As an E3 ubiquitin ligase, Fbxo4 loss leads to the accumulation of Fxr1; while the ectopic expression of Fbxo4 reduces Fxr1 levels, resulting in the elevation of both p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 that can induce the senescence of HNSCC cells [10].

3.5. Other Biological Functions

Under glutamine-depleted conditions, the loss of Fbxo4 leads to the accumulation of cyclin D1, which at least partially enhances apoptosis in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, NIH3T3 cells and ESCC cells [34]. However, the overexpression of Fbxo4 destabilizes Mcl-1 in human NSCLC cells, resulting in apoptosis when exposing cells to chemotherapeutic compounds, such as Cisplatin or Paclitaxel [39]. These findings suggest that distinct effects of Fbxo4 on apoptosis are context-dependent, i.e., the effects depend on cell type or genetic background. As such, further studies are required to dissect the detailed molecular mechanisms.

In addition, Fbxo4 also regulates the metastasis of breast cancer cells through controlling the stability of ICAM-1, which regulates the expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers, including E-cadherin (CDH1), Vimentin (VIM), Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1), and Snail Family Transcriptional Repressor 2 (SNAI2/SLUG) [40]. Overexpression of Fbxo4 not only reduces the size and weight of primary tumor xenografts, but also compromises the formation of metastatic tumors. Moreover, elevated Fbxo4 levels are correlated with longer survival in comparison to those with low Fbxo4 expression in breast cancer patients.

References

- Radke, S.; Pirkmaier, A.; Germain, D. Differential expression of the F-box proteins Skp2 and Skp2B in breast cancer. Oncogene 2005, 24, 3448–3458.

- Seo, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, R.; Yun, S.; Kim, M.; Han, J.K.; Costantini, F.; Jho, E.H. Multiple isoforms of beta-TrCP display differential activities in the regulation of Wnt signaling. Cell Signal 2009, 21, 43–51.

- Zhang, W.; Koepp, D.M. Fbw7 isoform interaction contributes to cyclin E proteolysis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2006, 4, 935–943.

- Chu, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Tu, J.; Sun, S.; Chen, X.; Lu, F. Alternative splicing variants of human Fbx4 disturb cyclin D1 proteolysis in human cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 447, 158–164.

- Barbash, O.; Diehl, J.A. SCF(Fbx4/alphaB-crystallin) E3 ligase: When one is not enough. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2983–2986.

- Li, Y.; Hao, B. Structural basis of dimerization-dependent ubiquitination by the SCF(Fbx4) ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13896–13906.

- Barbash, O.; Zamfirova, P.; Lin, D.I.; Chen, X.; Yang, K.; Nakagawa, H.; Lu, F.; Rustgi, A.K.; Diehl, J.A. Mutations in Fbx4 inhibit dimerization of the SCF(Fbx4) ligase and contribute to cyclin D1 overexpression in human cancer. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 68–78.

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404.

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal 2013, 6, pl1.

- Qie, S.; Majumder, M.; Mackiewicz, K.; Howley, B.V.; Peterson, Y.K.; Howe, P.H.; Palanisamy, V.; Diehl, J.A. Fbxo4-mediated degradation of Fxr1 suppresses tumorigenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1534.

- Cao, H.; Gao, R.; Yu, C.; Chen, L.; Feng, Y. The RNA-binding protein FXR1 modulates prostate cancer progression by regulating FBXO4. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2019, 19, 487–496.

- Majumder, M.; Johnson, R.H.; Palanisamy, V. Fragile X-related protein family: A double-edged sword in neurodevelopmental disorders and cancer. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 55, 409–424.

- Herzog, R.; Sacnun, J.M.; Gonzalez-Mateo, G.; Bartosova, M.; Bialas, K.; Wagner, A.; Unterwurzacher, M.; Sobieszek, I.J.; Daniel-Fischer, L.; Rusai, K.; et al. Lithium preserves peritoneal membrane integrity by suppressing mesothelial cell alphaB-crystallin. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eaaz9705.

- Mishra, S.; Wu, S.Y.; Fuller, A.W.; Wang, Z.; Rose, K.L.; Schey, K.L.; McHaourab, H.S. Loss of alphaB-crystallin function in zebrafish reveals critical roles in the development of the lens and stress resistance of the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 740–753.

- den Engelsman, J.; Bennink, E.J.; Doerwald, L.; Onnekink, C.; Wunderink, L.; Andley, U.P.; Kato, K.; de Jong, W.W.; Boelens, W.C. Mimicking phosphorylation of the small heat-shock protein alphaB-crystallin recruits the F-box protein FBX4 to nuclear SC35 speckles. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 4195–4203.

- den Engelsman, J.; Keijsers, V.; de Jong, W.W.; Boelens, W.C. The small heat-shock protein alpha B-crystallin promotes FBX4-dependent ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4699–4704.

- Lin, D.I.; Barbash, O.; Kumar, K.G.; Weber, J.D.; Harper, J.W.; Klein-Szanto, A.J.; Rustgi, A.; Fuchs, S.Y.; Diehl, J.A. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin D1 by the SCF(FBX4-alphaB crystallin) complex. Mol. Cell 2006, 24, 355–366.

- Barbash, O.; Egan, E.; Pontano, L.L.; Kosak, J.; Diehl, J.A. Lysine 269 is essential for cyclin D1 ubiquitylation by the SCF(Fbx4/alphaB-crystallin) ligase and subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation. Oncogene 2009, 28, 4317–4325.

- Lin, D.I.; Lessie, M.D.; Gladden, A.B.; Bassing, C.H.; Wagner, K.U.; Diehl, J.A. Disruption of cyclin D1 nuclear export and proteolysis accelerates mammary carcinogenesis. Oncogene 2008, 27, 1231–1242.

- Jin, X.; Moskophidis, D.; Hu, Y.; Phillips, A.; Mivechi, N.F. Heat shock factor 1 deficiency via its downstream target gene alphaB-crystallin (Hspb5) impairs p53 degradation. J. Cell Biochem. 2009, 107, 504–515.

- Barbash, O.; Lee, E.K.; Diehl, J.A. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of SCF(Fbx4) dimerization and activity involves a novel component, 14-3-3varepsilon. Oncogene 2011, 30, 1995–2002.

- Barbash, O.; Lin, D.I.; Diehl, J.A. SCF Fbx4/alphaB-crystallin cyclin D1 ubiquitin ligase: A license to destroy. Cell Div. 2007, 2, 2.

- Korcheva, V.B.; Levine, J.; Beadling, C.; Warrick, A.; Countryman, G.; Olson, N.R.; Heinrich, M.C.; Corless, C.L.; Troxell, M.L. Immunohistochemical and molecular markers in breast phyllodes tumors. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2011, 19, 119–125.

- Lee, E.K.; Lian, Z.; D’Andrea, K.; Letrero, R.; Sheng, W.; Liu, S.; Diehl, J.N.; Pytel, D.; Barbash, O.; Schuchter, L.; et al. The FBXO4 tumor suppressor functions as a barrier to BRAFV600E-dependent metastatic melanoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 4422–4433.

- Pontano, L.L.; Aggarwal, P.; Barbash, O.; Brown, E.J.; Bassing, C.H.; Diehl, J.A. Genotoxic stress-induced cyclin D1 phosphorylation and proteolysis are required for genomic stability. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 7245–7258.

- Aggarwal, P.; Lessie, M.D.; Lin, D.I.; Pontano, L.; Gladden, A.B.; Nuskey, B.; Goradia, A.; Wasik, M.A.; Klein-Szanto, A.J.; Rustgi, A.K.; et al. Nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1 during S phase inhibits Cul4-dependent Cdt1 proteolysis and triggers p53-dependent DNA rereplication. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 2908–2922.

- Aggarwal, P.; Vaites, L.P.; Kim, J.K.; Mellert, H.; Gurung, B.; Nakagawa, H.; Herlyn, M.; Hua, X.; Rustgi, A.K.; McMahon, S.B.; et al. Nuclear cyclin D1/CDK4 kinase regulates CUL4 expression and triggers neoplastic growth via activation of the PRMT5 methyltransferase. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 329–340.

- Tan, R.; Nakajima, S.; Wang, Q.; Sun, H.; Xue, J.; Wu, J.; Hellwig, S.; Zeng, X.; Yates, N.A.; Smithgall, T.E.; et al. Nek7 Protects Telomeres from Oxidative DNA Damage by Phosphorylation and Stabilization of TRF1. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 818–831.e815.

- Qian, L.; Zhang, F.; Yin, M.; Lei, Q. Cancer metabolism and dietary interventions. Cancer Biol. Med. 2021, 19, 163.

- Qie, S.; Chu, C.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Sang, N. ErbB2 activation upregulates glutaminase 1 expression which promotes breast cancer cell proliferation. J. Cell Biochem. 2014, 115, 498–509.

- Qie, S.; Liang, D.; Yin, C.; Gu, W.; Meng, M.; Wang, C.; Sang, N. Glutamine depletion and glucose depletion trigger growth inhibition via distinctive gene expression reprogramming. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 3679–3690.

- Dong, M.; Miao, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Han, J.; Yu, R.; Qie, S. Nuclear factor-kappaB p65 regulates glutaminase 1 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 3721–3729.

- Yu, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, L.; Yuan, S.; Xin, Y. Targeting GLS1 to cancer therapy through glutamine metabolism. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 2253–2268.

- Qie, S.; Yoshida, A.; Parnham, S.; Oleinik, N.; Beeson, G.C.; Beeson, C.C.; Ogretmen, B.; Bass, A.J.; Wong, K.K.; Rustgi, A.K.; et al. Targeting glutamine-addiction and overcoming CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1296.

- Rufini, A.; Tucci, P.; Celardo, I.; Melino, G. Senescence and aging: The critical roles of p53. Oncogene 2013, 32, 5129–5143.

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; Nehme, J.; Demaria, M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 436–453.

- Rayess, H.; Wang, M.B.; Srivatsan, E.S. Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 1715–1725.

- Majumder, M.; House, R.; Palanisamy, N.; Qie, S.; Day, T.A.; Neskey, D.; Diehl, J.A.; Palanisamy, V. RNA-Binding Protein FXR1 Regulates p21 and TERC RNA to Bypass p53-Mediated Cellular Senescence in OSCC. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006306.

- Feng, C.; Yang, F.; Wang, J. FBXO4 inhibits lung cancer cell survival by targeting Mcl-1 for degradation. Cancer Gene Ther. 2017, 24, 342–347.

- Kang, J.H.; Choi, M.Y.; Cui, Y.H.; Kaushik, N.; Uddin, N.; Yoo, K.C.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.J. Regulation of FBXO4-mediated ICAM-1 protein stability in metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 83100–83113.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

673

Revisions:

4 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No