Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wahiba Abu-Ras | -- | 1823 | 2022-06-13 21:29:40 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -8 word(s) | 1815 | 2022-06-14 03:22:06 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Abu-Ras, W.; Elzamzamy, K.; , .; Hamad Almerri, N.; Alajrad, M.; Kharbanda, V. Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being in Qatar. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23985 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Abu-Ras W, Elzamzamy K, , Hamad Almerri N, Alajrad M, Kharbanda V. Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being in Qatar. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23985. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Abu-Ras, Wahiba, Khalid Elzamzamy, , Noora Hamad Almerri, Moumena Alajrad, Vardha Kharbanda. "Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being in Qatar" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23985 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Abu-Ras, W., Elzamzamy, K., , ., Hamad Almerri, N., Alajrad, M., & Kharbanda, V. (2022, June 13). Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being in Qatar. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23985

Abu-Ras, Wahiba, et al. "Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being in Qatar." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

The impact of gendered citizenship on the well-being of cross-national families following the political blockade imposed on Qatar in 2017. More specifically, it examines how these families, women, and children face challenges related to their lives, well-being, and rights. Twenty-three face-to-face interviews were conducted with Qatari and non-Qatari women and men married to non-Qatari spouses residing in Qatar.

gendered citizenship

family cohesion

social inequality

1. Cross-National Marriage and Citizenship Law in the State of Qatar

The cross-national marriage defines as “the union of two nationals from different countries and typically involves the migration of one member of the couple” [1] (p. 187). Such marriages may result in gender inequality and challenges in accessing full citizenship and residency rights, and they undermine national identity [2]. They may also influence cultural norms, masculine authority, and traditional citizenship laws and policies.

Cross-national marriages are common in the Middle East and the Gulf region. In Qatar, for instance, their rate increased from 16.5% to 21% between 1985 and 2015 [3]. The highest rate of Qatari women marrying men from GCC countries was in 1985 (9.9%) [4]. This kind of marriage resulted in one of the Qatari state’s first attempts to directly regulate family life. Additionally, the DIFI study showed that the greater instability of cross-national marriages resulted in a disproportionate number of divorces, affected Qatari women’s ability to transmit their nationality to their children, and made them less likely to marry foreigners. Qatari women believe that such marriages are cost-effective because their similar backgrounds are similar to those of people from other GCC countries and because of their exposure to different cultures [5]. However, the blockade has caused the number of cross-national marriages among Qatari women to decline from 124 to 19 [6][7][8]. Simultaneously, the divorce rate among these couples has increased from 25 cases in 2018 to 32 cases in 2019 [9]. Given the decline in the overall number of cross-national marriages, the blockade have may significantly affected these rates. Alternative explanations may be related to the Qatari government’s policy of providing incentives to newlywed Qataris, such as subsidizing wedding venues, or to the government’s direct intervention in the regulation of family life [10].

The dearth of relevant research makes it difficult to determine the exact number of such marriages in each GCC country and the real reason(s) for their increase or decrease rate. In addition, these marriages pose a threat to Qatar’s culture and heritage, since non-citizens outnumber citizens [11][12]. Nonetheless, Qatari women are beginning to realize how difficult it is to pass their citizenship on to their children.

2. State Law and Gender-Based Citizenship in Qatar: Heritage and Progress

Citizenship in most Arab countries is passed on blood and/or land. This law is controversial because it is based on a patriarchal system that prioritizes men over women [13]. Therefore, most Arab women married to foreigners cannot confer their nationality upon their children or husbands and often lose their original citizenship after marriage. The Gulf region has a complex citizenship hierarchy based on tribal, familial, economic, sectarian, and gender factors [14]. It gives the state exclusive jurisdiction to define citizenship and standardize it according to criteria and rights, responsibilities, and obligations. Beyond citizenship, rights are legal, social, political, economic, cultural, and intellectual practices. Consequently, these factors affect people’s access to rights and membership and shape their sense of belonging to communities, as well as their sense of self-worth and national identity [15]. The concept of citizenship also refers to people’s rights and freedom, their duties, and their expectation that the state will protect them from sudden changes by ensuring their health, thereby leading to higher civic participation. The state regulates citizenship by establishing eligibility policies to determine who may pass their citizenship on to their children or spouse and who may lose it [16].

Gendered citizenship refers to a differential relationship between the state and citizens based on gender, which leads to disparities in citizenship rights [17]. According to Chari [18], it has three aspects. The first aspect is the binary of the private and the public, with the public referring to material issues and the private to cultural matters. Second, the framing of rights within the social structures of caste, class, and ethnicity causes women to experience rights differently. Third, societal differences are conceptualized in light of multiple patriarchies. For example, according to Qatar’s Nationality law, Article 5, Act No. 38, of 2005, Qatari women “cannot confer nationality on their children under any circumstance and cannot confer nationality to their foreign spouses, if they are married to a non-citizen”. However, in Article 1.4 of Act No. 38 of 2005, Qatari men automatically confer nationality on their children and spouses, regardless of whether they are born abroad or in the country. The discourses on these two bodies of law intersect because marriage is one route to citizenship.

Qatar is also one of the eight most difficult countries in which to obtain citizenship. Law 38, Article 2, 2005 states that foreigners must be legal residents for 25 years before applying. Legally, divorced women can apply for a land loan only five years after their divorce. This reality has more than legal repercussions; it carries a social implication that negatively affects self-esteem and relationships [19]. In other words, the state’s law is the main force behind gendered citizenship. Consequently, denying women full citizenship status not only hinders their access to essential resources, but further impairs their well-being and that of their families [20].

Qatar is moving from a traditional to a modern society, forming new identities and redesigning conventional social roles. The High Commissioner for Human Rights report (2019) shows that the Qatari government actively empowers women, increases their leadership roles, and ensures their inclusion in the Shura Council. Women’s social roles in society are also changing, as more of them are attending colleges and working outside the home. Furthermore, they are more present in education, business, political leadership roles, and many other fields. “Nationalization”, also known as “Qatarization”, advocates the hiring of more local workers in the public and private sectors, thereby increasing opportunities for women to work in administrative roles and develop entrepreneurial skills [21]. The Qatari government also offers citizens many benefits: subsidized utilities, free healthcare, education, land grants, affordable housing, and an array of others [22]. Most recently, the children of Qatari women have begun to gain permanent residency rights due to a new law introduced during the blockade and implemented on 22 December 2020 [23]. This development represents an encouraging step toward ensuring the full citizenship rights of all women and children. However, Qatari women who marry foreigners still cannot pass on their citizenship to their children, a reality that further compromises gender equality and denies women full rights.

3. Citizenship and Well-Being

One definition of citizenship holds that it is “a relationship between citizens and the government that is built on rights and obligations and the principle of inclusion and exclusion” [18] (p. 47). A newer definition stresses everyday functioning and emphasizes that political regulation alone cannot solve social issues. However, this discussion would benefit from academic input from the fields of, for example, sociology, public health, and family relations to explain and increase citizens’ well-being [24]. Citizenship is perceived as a privilege and a source of personal, national, and political identity [25]. Moreover, it provides rights and freedoms that promote a sense of self-worth and guarantees membership in a social group while holding people accountable for social, economic, and political decisions.

The World Health Organization defines well-being as referring to a state of “complete physical, mental, and social well-being, instead of just being free of disease or infirmity” [26]. Subjective well-being is conceptualized through three interrelated components: life satisfaction, pleasant affect, and unpleasant affect [27]. The term “affect” describes mood and emotions, whereas life satisfaction describes cognitive satisfaction with life [28]. One must possess positive emotion, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and accomplishment to achieve positive well-being [29]. However, this concept has been widely debated due to its complexity.

The objective approach covers “quality of life indicators such as material resources (e.g., income, food, housing) and social attributes (education, health, political voice, social networks and connections” [30] (p. 2). However, the definition and measurement of objective well-being have always posed a challenge. Therefore, it has been suggested that its dimensions should be explored rather than its definition [31].

As modern society has developed, a broader understanding of well-being has emerged around public health issues. State policies and practices are believed to impact people’s physical and mental health, particularly within families. In this vein, well-being is concerned with the objective and subjective aspects of individual well-being to inform policymakers and update international statistical indicators, such as the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Index [32][33][34]. Furthermore, some developed countries use well-being indicators to assess how state policies impact citizens’ well-being [35].

Demographic factors can also have a direct influence in this regard. In some countries, policymakers evaluate objective well-being based on such economic and wealth measures as, among others, household income, per capita production, and gross domestic product [36]. For instance, Qataris perceive socioeconomic status, religious affiliation, employment status, and trust in the government as its most essential determinants [37].

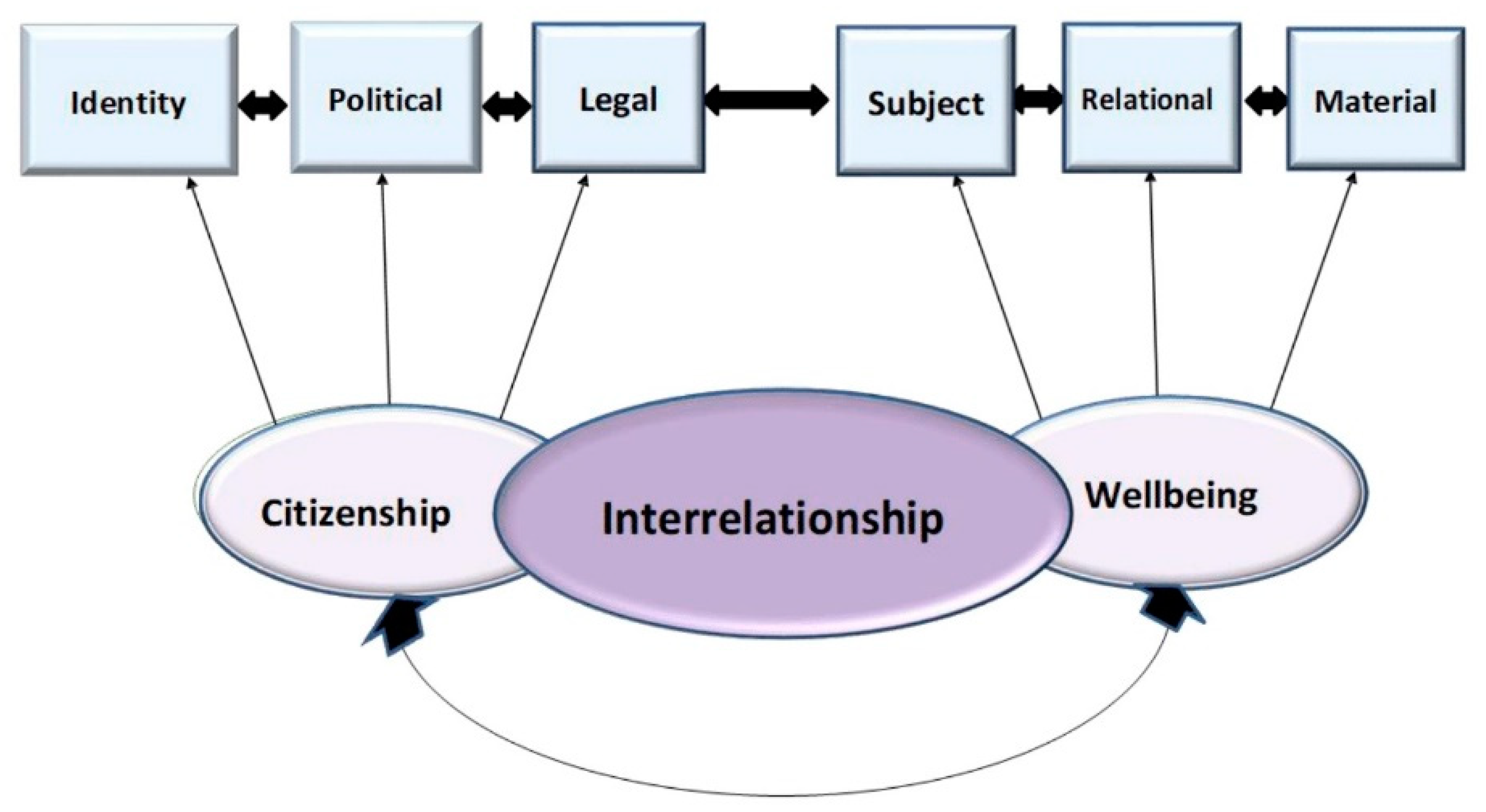

The concepts of citizenship and well-being have dimensions that overlap, intersect, or interconnect. The various definitions of citizenship and well-being illustrate that both concepts are complex and different in each society. To address this complexity, researchers created a new conceptual multidimensional paradigm (see Figure 1) to illustrate this overlap using Leydet and White’s definitions of citizenship and well-being, respectively [38][39].

Figure 1. Multidimensional Model.

4. Perceived Interrelationship between Citizenship and Well-Being: A New Multidimensional Paradigm

This section illustrates the dimensions of citizenship and well-being and their interrelationship by using the arguments and definitions presented by Leydet and White. According to Leydet, citizenship consists of three dimensions: the law, politics, and identity. The legal dimension includes the civil, political, and social rights under which citizens have the freedom to enact laws and receive protection from them. The political dimension refers to citizens’ active role in a society’s political institutions. The identity dimension refers to citizenship as belonging (relational) to a specific group of people who share a common identity (e.g., national, political, social, and cultural). This dimension, also known as the psychological dimension, fosters belonging to one’s family, community, and society [38].

Similarly, White suggested three dimensions of well-being: subjective, relational, and material. The subjective dimension focuses on what people value and believe is right, along with their feelings and desires about themselves. It includes hope, fear, anxiety, satisfaction, trust, and confidence. The social or relational dimension includes relationships of love and care, social networks, and interactions with the state regarding law enforcement, local or national politics, social welfare, and security. The material dimension includes items commonly referred to as “human capital” or “abilities”, including income, wealth, employment, education, access to services, and the quality of the environment, as well as social capabilities, such as belonging to and inclusion in social groups and networks. In addition, it stresses the notions of trust, inclusion, membership, cohesion, and quality of life. It is determined by how people participate in their current and past social, cultural, and political lives [39].

References

- Riley, N.E.; Brunson, J. International Handbook on Gender and Demographic Processes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Longo, G.M. Keeping it in “the family”: How gender norms shape US marriage migration politics. Gend. Soc. 2018, 32, 469–492.

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.P.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L.D. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235.

- Alharahsheh, S.T.; Mohieddin, M.M.; Almeer, F.K. Marrying Out: Trends and Patterns of Mixed Marriage amongst Qataris. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2015, 3, 211.

- Caeiro, A. The Politics of Family Cohesion in the Gulf: Islamic Authority, new Media, and the Logic of the Modern Rentier State. Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2018.

- Monthly Statistics for Web Final: Ministry of Developed Planning and Statistics. Population. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics1/pages/topicslisting.aspx?parent=population&child=population (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Monthly Statistics for Web Final: Ministry of Developed Planning and Statistics. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics1/pages/topicslisting.aspx?parent=General&child=QMS (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Monthly Statistics for Web Final: Ministry of Developed Planning and Statistics. Marriage and Divorce. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics1/pages/topicslisting.aspx?parent=Population&child=MarriagesDivorces (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Nitsevich, V.F.; Moiseev, V.V.; Sudorgin, O.A.; Stroev, V.V. Why Russia Cannot Become the Country of Prosperity. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 272, 032148.

- Babar, Z. Population, Power, and Distributional Politics in Qatar. J. Arab. Stud. 2015, 5, 138–155.

- Davidson, C.M. Dubai: The Vulnerability of Success; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- Joseph, S. Intimate Selving in Arab Families: Gender, Self, and Identity; Syracuse University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999.

- Sater, J. Migration and the Marginality of Citizenship in the Arab Gulf Region: Human Security and High Modernist Tendencies; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 224–245.

- Mackert, J.; Turner, B.S. The Transformation of Citizenship, Volume 2: Boundaries of Inclusion and Exclusion; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Joseph, S. Gender and Citizenship in the Arab World. Al-Raida J. 1970, 129, 8–18.

- Amri, L.; Ramtohul, R. Gender and Citizenship in the Global Age; African Books Collective-CODESRIA : Dakar, Senegal, 2015.

- Chari, W.A. Gendered citizenship and women’s movement. EPW 2009, 44, 47–57.

- El-Saadani, S.M. Divorce in the Arab Region: Current Levels, Trends and Features. In Proceeding of the European Population Conference, Liverpool, UK, 23 June 2006.

- Oldfield, S.; Mathsaka, N.S.; Salo, E.; Schlyter, A. In bodies and homes: Gendering citizenship in Southern African cities. Urbani Izziv 2019, 30, 37–51.

- Tok, M.E.; Alkhater, L.R.; Pal, L.A. Policy-Making in a Transformative State: The Case of Qatar. In Policy-Making in a Transformative State; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016.

- Mitchell, J.S.; Paschyn, C.; Mir, S.; Pike, K.; Kane, T. Inmajaalis al-hareem: The complex professional and personal choices of Qatari women. DIFI Fam. Res. Proc. 2015, 2015, 4.

- Shura Council Reviews Recommendations to Grant P.R. to Children of Qatari Women Married to Non-Qataris. Qatar Tribune. Available online: https://www.qatar-tribune.com/news-details/id/204380 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Lewicka, M. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 381–395.

- Constitution of the World Health Organization. Basic Documents, 51st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Gee, G.C.; Morey, B.N.; Walsemann, K.M.; Ro, A.; Takeuchi, D.T. Citizenship as privilege and social identity: Implications for psychological distress. Am. Behav. Sci. 2016, 60, 680–687.

- Diener, E.D.; Suh, M.E. Subjective well-being and age: An international analysis. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr 1997, 17, 304–324.

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and Open Questions in the Science of Subjective Well-Being. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 15.

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 13, 333–335.

- Western, M.; Tomaszewski, W. Subjective well-being, objective well-being and inequality in Australia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163345.

- McNaught, A. Defining Wellbeing. In Understanding Wellbeing: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners of Health and Social Care; Knight, A., McNaught, A., Eds.; Banbury: Lantern, Singapore, 2011; pp. 7–23.

- Hicks, S.; Tinkler, L.; Allin, P. Measuring Subjective Well-Being and its Potential Role in Policy: Perspectives from the UK Office for National Statistics. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 73–86.

- Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.215.58&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- La Placa, V.; McNaught, A.; Knight, A. Discourse on wellbeing in research and practice. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3, 116–125.

- Boarini, R.; Johansson, Å.; Mira d’Ercole, M. Alternative Measures of Well-Being. OECD 2006, 1–57.

- Nasser, N.; Fakhroo, H. An Investigation of the Self-Perceived Well-Being Determinants: Empirical Evidence from Qatar. SAGE 2021, 1–11.

- Leydet, D. Citizenship; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Standford, CA, USA, 2008.

- White, S.C. But What is Well-Being? A Framework for Analysis in Social and Development Policy and Practice. In Conference on Regeneration and Well-Being: Research into Practice University of Bradford, 24-25 April 2008; University of Bradford: Bradford, UK, 2008.

- Clayton, A.; O’Connell, M.J.; Bellamy, C.; Benedict, P.; Rowe, M. The Citizenship Project Part II: Impact of a Citizenship Intervention on Clinical and Community Outcomes for Persons with Mental Illness and Criminal Justice Involvement. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 51, 114–122.

- Georghiades, A.; Eiroa-Orosa, F.J. A Randomised Enquiry on the Interaction Between Wellbeing and Citizenship. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 2115–2139.

More

Information

Subjects:

Social Work

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

4.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No