| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mahmoud Ibraheam Saleh | -- | 3317 | 2022-05-31 12:35:02 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -14 word(s) | 3303 | 2022-06-01 03:57:45 | | |

Video Upload Options

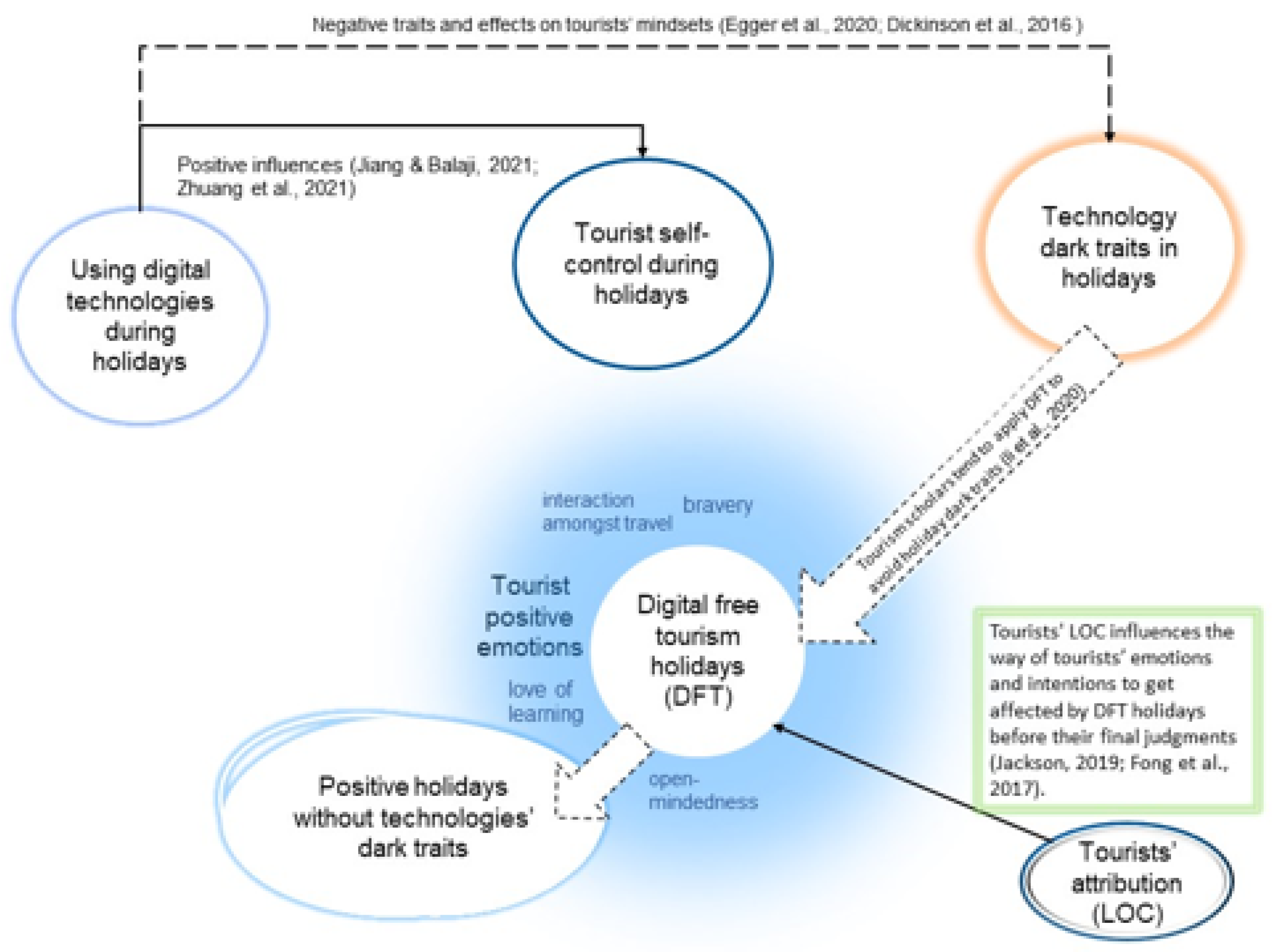

Digital-free tourism (DFT) has recently attracted tourism service providers’ attention for its benefits in terms of enhancing tourists’ experiences and well-being at destinations. DFT refers to tourists who are likely to voluntarily avoid digital devices and the Internet on holiday, or travel to destinations without network signals. DFT has advantages for tourists in increasing well-being, mental health, and social networking during their journeys. DFT also has a benefit for tourism marketers in that they can consider it as a new tourism approach.

1. Introduction

2. Digital Significance for Tourists during Holidays

3. Digital-Free Tourism (DFT) and Tourists’ Locus of Control (LOC)

DFT has advantages to increase tourists' well-being and satisfaction depending on their self-control during DFT holidays. The study proposes nuanced propositions to help destination managers to encourage tourists to engage in DFT holidays by avoiding obstacles that may cause low self-control during DFT holidays as follows:

On the one hand, to encourage tourists for digital detox during holidays, destination managers are recommended to list the benefits of digital detox by highlighting tourists' reviews about experiencing digital detox holidays on their websites. Tourism destination managers are also recommended to specialize a prominent icon on their websites and/or mobile applications during the reservation, notifying tourists about self-growth opportunities by evading digital technology use during the journey [9]. On the other hand, to avoid tourists' lower self-control as an output because of lack of information and emergencies during DFT holidays. Destination managers are recommended to distribute informative vouchers that include all information about the city tourists help centers, transportations schedules, prices; restaurant working times; pharmacies and hospitals numbers, public toilet’s locations, foreign exchange centers, and police stations.

Furthermore, destination managers are recommended to ensure a prompt service encounter process, especially waiting times, to ensure that tourists participate in digital-free tourism during holidays. For example, destination managers should avoid waiting times while checking in because more waiting time increases the likelihood of an external LOC [30]. This, in turn, will motivate tourists to pick up their mobile phones and ignore the DFT challenge. Therefore, destination managers should add a new option to their website to facilitate check-in procedures for tourists before tourists' arrival. Additionally, there is a high positive correlation between addiction to digital devices, loneliness, and low self-control -external LOC- [38]. Therefore, destination managers should involve single-accommodate DFT tourists at destinations with entertainment activities at hotels by prioritizing them with hotel entertainment activities compared with tourists with companions.

Tourist orientation from tour operators about the new tourism trends helps cope with the lingering self-distress tourists may encounter during holidays. Travelers who engage in DFT holiday patterns are more likely to mirror low post-traumatic self-confidence of digital detox. Therefore, tour operators (e.g., individual and/or team organizers in different tourism destinations) have to create pre-FDT orientations in an easy way to avoid DFT obstacles. Tour operators are recommended to clarify and explore the predicted sudden and dramatic low self-confidence or low self-control tourists may encounter during the DFT holiday, the emergencies they may encounter, and the solution to cover these obstacles. Such a burning urge for "orientation" helps tourists enjoy their DFT holidays through pre-FDT orientation helps them help signify the barriers and avoid them to increase their sense of control and normalcy.

According to Galvin et al. [27], individuals who shift from external to primarily internal lead to positive feelings with high satisfaction and control the outcomes of their events (DFT holidays). Individuals with external LOC are less likely to control DFT holidays; thus, destination managers may propose the #Digital_Detox_Challenge hashtag with incentives. So, if tourists join the challenge and achieve success in this challenge, destination managers could upgrade their reservations with discounts. This will raise the tourists' self-confidence, influencing individuals to have Internal LOC [12].

References

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019.

- Calderwood, L.U.; Soshkin, M. The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, S.; Chaudhary, M. Are small travel agencies ready for digital marketing? Views of travel agency managers. Tour. Manag. 2020, 79, 104078.

- Cai, W.; McKenna, B.; Waizenegger, L. Turning It Off: Emotions in Digital-Free Travel. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 909–927.

- Melović, B.; Jocović, M.; Dabić, M.; Vulić, T.B.; Dudic, B. The impact of digital transformation and digital marketing on the brand promotion, positioning and electronic business in Montenegro. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101425.

- Cuomo, M.T.; Tortora, D.; Foroudi, P.; Giordano, A.; Festa, G.; Metallo, G. Digital transformation and tourist experience co-design: Big social data for planning cultural tourism. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120345.

- Halbheer, D.; Stahl, F.; Koenigsberg, O.; Lehmann, D.R. Choosing a digital content strategy: How much should be free? Int. Res. J. Mark. 2014, 31, 192–206.

- Mak, A.H.N. Online destination image: Comparing national tourism organisation’s and tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 280–297.

- Li, J.; Pearce, P.L.; Oktadiana, H. Can digital-free tourism build character strengths? Ann. Tour Res. 2020, 85, 103037.

- Egger, I.; Lei, S.I.; Wassler, P. Digital free tourism—An exploratory study of tourist motivations. Tour. Manag. 2020, 79, 104098.

- Li, J.; Pearce, P.L.; Low, D. Media representation of digital-free tourism: A critical discourse analysis. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 317–329.

- Jackson, M. Utilizing attribution theory to develop new insights into tourism experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 176–183.

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Munyanyi, M.E.; Prakash, K.; Smyth, R. Locus of control and the gender gap in mental health. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 178, 740–758.

- Abay, K.A.; Blalock, G.; Berhane, G. Locus of control and technology adoption in developing country agriculture: Evidence from Ethiopia. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 143, 98–115.

- Fong, L.H.N.; Lam, L.W.; Law, R. How locus of control shapes intention to reuse mobile apps for making hotel reservations: Evidence from chinese consumers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 331–342.

- Krings, W.; Palmer, R.; Inversini, A. Industrial marketing management digital media optimization for B2B marketing. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 174–186.

- Kannan, P.K.; Li, H.A. Digital marketing: A framework, review and research agenda. Int. Res. J. Mark. 2017, 34, 22–45.

- Shankar, V.; Smith, A.K.; Rangaswamy, A. Customer satisfaction and loyalty in online and offline environments. Int. Res. J. Mark. 2003, 20, 153–175.

- Pawłowska-Legwand, A.; Matoga, Ł. Disconnect from the Digital World to Reconnect with the Real Life: An Analysis of the Potential for Development of Unplugged Tourism on the Example of Poland. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 18, 649–672.

- Dickinson, J.E.; Hibbert, J.F.; Filimonau, V. Mobile technology and the tourist experience: (Dis)connection at the campsite. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 193–201.

- Floros, C.; Cai, W.; McKenna, B.; Ajeeb, D. Imagine being off-the-grid: Millennials’ perceptions of digital-free travel. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 751–766.

- Zhuang, X.; Hou, X.; Feng, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, J. Subjective norms, attitudes, and intentions of AR technology use in tourism experience: The moderating effect of millennials. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 392–406.

- Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Refaat, S.A. The Impact of Eatmarna Application Usability on Improving Performance Expectancy, Facilitating the Practice of Rituals and Improving Spirituality Feelings during Umrah Amid the COVID-19 Outbreak. Religions 2022, 13, 268.

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R. Investigating the effects of offline and online social capital on tourism SME performance: A mixed-methods study of New Zealand entrepreneurs. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104128.

- Douglass, M.D.; Bain, S.A.; Cooke, D.J.; McCarthy, P. The role of self-esteem and locus-of-control in determining confession outcomes. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 147, 292–296.

- Toti, J.-F.; Diallo, M.F.; Huaman-Ramirez, R. Ethical sensitivity in consumers’ decision-making: The mediating and moderating role of internal locus of control. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 168–182.

- Galvin, B.M.; Randel, A.E.; Collins, B.J.; Johnson, R.E. Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 820–833.

- Eslami, H.; Kacker, M.; Hibbard, J.D. Antecedents of locus of causality attributions for destructive acts in distribution channels. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 302–314.

- Weiner, B. Attributional Thoughts about Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 382–387.

- Folkes, V.S.; Koletsky, S.; Graham, J.L. A Field Study of Causal Inferences and Consumer Reaction: The View from the Airport. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 534.

- Lin, M.P.; Marine-Roig, E.; Llonch-Molina, N. Gastronomy Tourism and Well-Being: Evidence from Taiwan and Catalonia Michelin-Starred Restaurants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2778.

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Sternthal, B. Gender differences in the use of message cues and judgments. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 84–96.

- Saleh, M.I. The effects of tourist’s fading memories on tourism destination brands’ attachment: Locus of control theory application. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 1198–1202.

- Karkoulian, S.; Srour, J.; Sinan, T. A gender perspective on work-life balance, perceived stress, and locus of control. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4918–4923.

- Saleh, M.I. Tourists’ interpretations toward tourism destinations: Viewpoint to apply locus of control theory. Tour. Critiq. 2021, 2, 222–234.

- Fan, X.; Jiang, X.; Deng, N. Immersive technology: A meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104534.

- Jiang, Y.; Balaji, M.S. Getting unwired: What drives travellers to take a digital detox holiday? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 1–17.

- Karpinska-Krakowiak, M. Women are more likely to buy unknown brands than men: The effects of gender and known versus unknown brands on purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102273.