| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seipati Mokhosi | -- | 1513 | 2022-05-26 22:10:12 | | | |

| 2 | Nora Tang | + 364 word(s) | 1877 | 2022-05-27 10:31:07 | | |

Video Upload Options

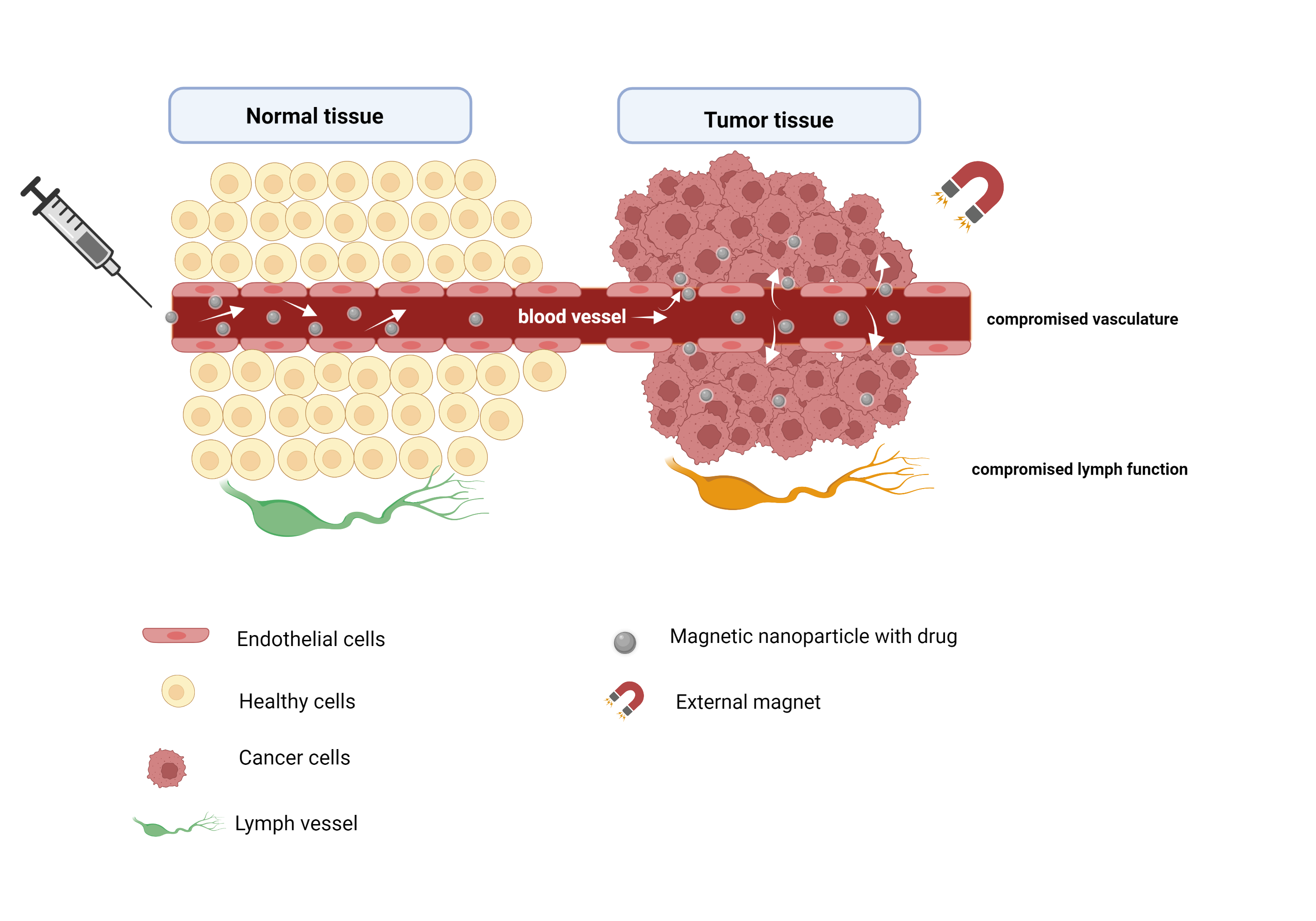

Cancer theranostics remains a vital research niche as a result of the rising mortality rates caused by various cancers globally. This is excarcebated by challenges related to conventional therapies. Iron-oxide-based NPs that possess characteristically large surface areas, small particle sizes, and superparamagnetism have been cited in applications geared towards diagnosis, and targeted drug delivery. When an external magnetic field is applied to superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs (SPIONs), the domains are aligned to the field. Once the field is removed, they return to a non-magnetic state. The NP magnetic moments turn to flip in the direction of the applied field. This flipping of the magnetic moments generates heat, which forms the basis of tumour ablation therapy through hyperthermia. Substituted iron-oxides or ferrites (MFe2O4) have emerged as interesting magnetic NPs due to their unique and attractive properties such as size and magnetic tunability, ease of synthesis, and manipulatable properties. In recent years, they have been explored for use in targeted therapy and drug delivery for anti-cancer treatment.

1. Magnetic Hyperthermia

| Trade/Generic Name/Clinical Trial ID | Nanocomposite Material | Application (Cancer Type) |

|---|---|---|

| Abdoscan®/Ferristene/OMP (Nycomed) | Polystyrene-coated iron oxide NPs | MRI imaging: gastrointestinal tract |

| Combidex® (USA), Sinerem® (EU), Ferumoxtran-10/AMI-277 (Guerbet/AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc) |

Iron oxide coated with dextran (T10) | MRI imaging: prostate, breast, bladder, genitourinary cancers, and lymph node metastases |

| Feraheme® (USA), Rienso® (EU)/Ferumoxytol (AMAG Pharmaceutical Inc.) |

Polyglucose-sorbitol-carboxymethyl-ether-coated iron oxide (γ-Fe2O3) | Imaging: rectal, oesophageal, bone, colorectal, prostate, bladder, kidney, lymph node, head and neck, breast, non-small cell lung, and pancreatic cancers; osteonecrosis, soft tissue sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, glioblastoma; melanoma |

| Feridex I.V. (USA), Endorem™ (EU), AMI-25/ferumoxides (AMAG Pharmaceuticals) | Iron oxide coated with dextran (T10) | MRI—liver/spleen imaging |

| Lumirem® (USA), GastroMARK® (EU), AMI- 121 (AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc/Guerbet) | Siloxane-coated iron oxide NPs | MRI Imaging: gastrointestinal tract |

| Resovist® (USA, Japan, EU) Cliavist® (France), Ferucarbotran/ SHU555A (Bayer Schering Pharma) |

Carboxydextran-coated iron oxide (γ-Fe2O3) | MRI imaging: liver/spleen tumours |

| Nanotherm™ (Magforce Nanotech AG) | Aminosilane-coated iron oxide NPs | Thermal ablation, hyperthermia local ablation in glioblastoma. |

| MagProbeTM (University of New Mexico) | Magnetic iron oxide NPs | Leukaemia |

| Magnablate I (University College London) | Iron NPs | Prostate cancer |

| NC100150/Clarisan/Feruglose/PEG-fero (Nycomed) | Carbohydrate-polyethylene-glycol-coated ultra-superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs | MRI imaging: tumour microvasculature |

| Sienna+® (Endomagnetics Ltd.) | Carboxydextran-coated iron oxide NPs | Breast and rectal cancer |

| NCT01895829 NTC03179449 NTC04369560 |

Polyglucose sorbitol carboxy methyl ether coated SPIONs | MRI detection for the spread of head and neck cancer MRI detection of inflammation (macrophage) in childhood brain neoplasm MRI detection for urinary bladder neoplasms |

| NCT01749280 NCT04316091 |

USPIONs | MRI to predict the growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms Neoadjuvant chemotherapy+ SPIONs/spinning magnetic field; evaluate tolerability, safety, and efficacy of the treatment: osteosarcoma |

| Ferumoxytol USPIO-MRI | Enhanced MRI | Enhanced MRI in imaging lymph nodes in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: head and neck cancer |

| Ferumoxytol MIONs | Ferumoxytol | Pilot feasibility study of MIONs MR dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for primary and nodal tumour imaging in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinomas |

2. Targeted Drug Delivery

3. Imaging Systems

References

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. A Review of Clinical Translation of Inorganic Nanoparticles. AAPS J. 2015, 17, 1041–1054.

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, W.; Lu, X.; Gao, X.; Xie, M.; Shan, Q.; Wen, N.; et al. Magnetic nanomaterials-mediated cancer diagnosis and therapy. Prog. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 4, 012005.

- Liang, C.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, M.; Huang, W.; Dong, X. Magnetic iron oxide nanomaterials: A key player in cancer nanomedicine. View 2020, 1, 20200046.

- Jeyadevan, B. Present status and prospects of magnetite nanoparticles-based hyperthermia. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 118, 391–401.

- Gul, S.; Khan, S.B.; Rehman, I.U.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.I. A Comprehensive Review of Magnetic Nanomaterials Modern Day Theranostics. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 179.

- Williams, H.M. The application of magnetic nanoparticles in the treatment and monitoring of cancer and infectious diseases. Biosci. Horiz. 2017, 10, hzx009.

- Zhu, N.; Ji, H.; Yu, P.; Niu, J.; Farooq, M.U.; Waseem Akram, M.; Udego, I.O.; Li, H.; Niu, X. Surface modification of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 810.

- Shirazi, H.; Daneshpour, M.; Kashanian, S.; Omidfar, K. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro biocompatibility study of Au/TMC/Fe3O4 nanocomposites as a promising, nontoxic system for biomedical applications. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 1677–1689.

- Patil, R.M.; Shete, P.B.; Thorat, N.D.; Otari, S.V.; Barick, K.C.; Prasad, A.; Ningthoujam, R.S.; Tiwale, B.M.; Pawar, S.H. Superparamagnetic iron oxide/chitosan core/shells for hyperthermia application: Improved colloidal stability and biocompatibility. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 355, 22–30.

- Suciu, M.; Ionescu, C.M.; Ciorita, A.; Tripon, S.C.; Nica, D.; Al-Salami, H.; Barbu-Tudoran, L. Applications of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in drug and therapeutic delivery, and biotechnological advancements. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 11, 1092–1109.

- Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, G.; Han, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Zheng, L.; et al. Leucine-coated cobalt ferrite nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and potential biomedical applications for drug delivery. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 384, 126600.

- Verma, J.; Lal, S.; Van Noorden, C.J.F. Nanoparticles for hyperthermic therapy: Synthesis strategies and applications in glioblastoma. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 2863–2877.

- Ulbrich, K.; Holá, K.; Šubr, V.; Bakandritsos, A.; Tuček, J.; Zbořil, R. Targeted Drug Delivery with Polymers and Magnetic Nanoparticles: Covalent and Noncovalent Approaches, Release Control, and Clinical Studies. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5338–5431.

- Li, Z.; Tan, S.; Li, S.; Shen, Q.; Wang, K. Cancer drug delivery in the nano era: An overview and perspectives. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 611–624.

- Golovin, Y.I.; Golovin, D.Y.; Vlasova, K.Y.; Veselov, M.M.; Usvaliev, A.D.; Kabanov, A.V.; Klyachko, N.L. Non-Heating Alternating Magnetic Field Nanomechanical Stimulation of Biomolecule Structures via Magnetic Nanoparticles as the Basis for Future Low-Toxic Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2255.

- Gribanovsky, S.L.; Zhigacheva, A.O.; Golovin, D.Y.; Golovin, Y.I.; Klyachko, N.L. Mechanisms and conditions for mechanical activation of magnetic nanoparticles by external magnetic field for biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 553, 169278.

- Broders-Bondon, F.; Ho-Bouldoires, T.H.N.; Fernandez-Sanchez, M.-E.; Farge, E. Mechanotransduction in tumor progression: The dark side of the force. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 1571–1587.

- García, R.S.; Stafford, S.; Gun’ko, Y.K. Recent progress in synthesis and functionalization of multimodal fluorescent-magnetic nanoparticles for biological applications. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 172.

- Martinelli, C.; Pucci, C.; Ciofani, G. Nanostructured carriers as innovative tools for cancer diagnosis and therapy. APL Bioeng. 2019, 3, 011502.

- Bertrand, N.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Kamaly, N.; Farokhzad, O.C. Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 66, 2–25.

- Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Orza, A.; Lu, Q.; Guo, P.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Mao, H. Magnetic Nanoparticle Facilitated Drug Delivery for Cancer Therapy with Targeted and Image-Guided Approaches. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3818–3836.

- Mirza, A.Z.; Siddiqui, F.A. Nanomedicine and drug delivery: A mini review. Int. Nano Lett. 2014, 4, 94.

- Estelrich, J.; Escribano, E.; Queralt, J.; Busquets, M.A. Iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetically-guided and magnetically-responsive drug delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 8070–8101.

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Nano Adv. 2016, 2, 25–38.

- Mahmoudi, M.; Sant, S.; Wang, B.; Laurent, S.; Sen, T. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs): Development, surface modification and applications in chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 24–46.

- Gao, H. Progress and perspectives on targeting nanoparticles for brain drug delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2016, 6, 268–286.

- Rosenblum, D.; Joshi, N.; Tao, W.; Karp, J.M.; Peer, D. Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1410.

- Arum, Y.; Oh, Y.O.; Kang, H.W.; Ahn, S.H.; Oh, J. Chitosan-coated Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles as carrier of cisplatin for drug delivery. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2015, 18, 89–98.

- Saif, B.; Wang, C.; Chuan, D.; Shuang, S. Synthesis and Characterization of of Fe3O4 magnetic nanofluid coated on APTES as Carriers for Morin-Anticancer Drug. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 6, 267–275.

- Kariminia, S.; Shamsipur, A.; Shamsipur, M. Analytical characteristics and application of novel chitosan coated magnetic nanoparticles as an efficient drug delivery system for ciprofloxacin. Enhanced drug release kinetics by low-frequency ultrasounds. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 129, 450–457.

- Karimi, Z.; Abbasi, S.; Shokrollahi, H.; Yousefi, G.; Fahham, M.; Karimi, L.; Firuzi, O. Pegylated and amphiphilic Chitosan coated manganese ferrite nanoparticles for pH-sensitive delivery of methotrexate: Synthesis and characterization. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 504–511.

- Mngadi, S.; Mokhosi, S.; Singh, M. Chitosan-functionalized Mg0.5Co0.5Fe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles enhance delivery of 5-fluorouracil in vitro. Coatings 2020, 10, 446.

- Jose, R.; Rinita, J.; Jothi, N.S.N. Synthesis and characterisation of stimuli-responsive drug delivery system using ZnFe2O4 and Ag1−XZnxFe2O4 nanoparticles. Mater. Technol. 2020, 36, 347–355.

- Nigam, A.; Pawar, S.J. Structural, magnetic, and antimicrobial properties of zinc doped magnesium ferrite for drug delivery applications. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 4058–4064.

- Javed, F.; Abbas, M.A.; Asad, M.I.; Ahmed, N.; Naseer, N.; Saleem, H.; Errachid, A.; Lebaz, N.; Elaissari, A.; Ahmad, N.M. Gd3+ Doped CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Magnetochemistry 2021, 7, 47.

- Malik, A.R.; Aziz, M.H.; Atif, M.; Irshad, M.S.; Ullah, H.; Gia, T.N.; Ahmed, H.; Ahmad, S.; Botmart, T. Lime peel extract induced NiFe2O4 NPs: Synthesis to applications and oxidative stress mechanism for anticancer, antibiotic activity. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2022, 26, 101422.

- Vigneswari, T.; Thiruramanathan, P. Magnetic Targeting Carrier Applications of Bismuth-Doped Nickel Ferrites Nanoparticles by Co-precipitation Method. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2021, 74, 2255–2265.

- Veiseh, O.; Gunn, J.; Zhang, M. Design and fabrication of magnetic nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery and imaging. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 62, 284–304.

- Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Łazarczyk, A.; Hałubiec, P.; Szafrański, O.; Karnas, K.; Karewicz, A. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles-current and prospective medical applications. Materials 2019, 12, 617.

- Dadfar, S.M.; Roemhild, K.; Drude, N.I.; von Stillfried, S.; Knüchel, R.; Kiessling, F.; Lammers, T. Iron oxide nanoparticles: Diagnostic, therapeutic and theranostic applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 138, 302–325.

- Khalkhali, M.; Rostamizadeh, K.; Sadighian, S.; Khoeini, F.; Naghibi, M.; Hamidi, M. The impact of polymer coatings on magnetite nanoparticles performance as MRI contrast agents: A comparative study. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23, 45.

- Kefeni, K.K.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Nkambule, T.T.; Mamba, B.B. Spinel ferrite nanoparticles and nanocomposites for biomedical applications and their toxicity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 107, 110314.

- Kandasamy, G.; Maity, D. Recent advances in superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) for in vitro and in vivo cancer nanotheranostics. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 496, 191–218.

- Zhang, Q.; Yin, T.; Gao, G.; Shapter, J.G.; Lai, W.; Huang, P.; Qi, W.; Song, J.; Cui, D. Multifunctional core @ shell magnetic nanoprobes for enhancing targeted magnetic resonance imaging and Fluorescent Labeling in Vitro and in Vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 17777–17785.