Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Georgios Giotis | -- | 2390 | 2022-05-26 11:36:52 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2390 | 2022-05-27 08:05:12 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | -32 word(s) | 2358 | 2022-05-27 11:09:23 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Giotis, G.; Papadionysiou, E. Managerial in the Tourism Industry. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23414 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Giotis G, Papadionysiou E. Managerial in the Tourism Industry. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23414. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Giotis, Georgios, Evangelia Papadionysiou. "Managerial in the Tourism Industry" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23414 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Giotis, G., & Papadionysiou, E. (2022, May 26). Managerial in the Tourism Industry. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23414

Giotis, Georgios and Evangelia Papadionysiou. "Managerial in the Tourism Industry." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

Globalization and intense competition force organizations to be flexible and adaptable to constant changes in the market. According to many researchers, innovation is a crucial source of competitive advantage in the continuously changing environment. Many studies in the area of management present innovation as one of the most significant factors for enhancing organizational performance.

managerial innovation

technological innovation

sustainable tourism development

1. Innovation Research

Innovation is considered as a crucial source of competitive advantage in a constantly changing environment [1][2]. Innovation capability is the most important determinant of organizational performance [3].

Definitions of innovation emphasize different aspects of the term. The first definition of innovation according to Schumpeter [4] is divided into “the categories of product innovation, process innovation, marketing innovation, input innovation and organizational innovation”. The European Commission [5] defined innovation as “new or renewed product/services, new markets, new production methods and changes in management”. Then, Hansen and Wakonen [6] stated that “it is practically impossible to do things identically”, which renders any change an innovation by default.

From Porter [7] until now, “not only innovation has been analyzed but also the factors that influence the ability to manage innovation”. Smith [8] identified some factors that affect the ability of a company to manage innovation. These key factors are “leadership/management style, resources, organizational structure, technology, corporate strategy, knowledge management, employees and innovation process”.

In addition, Peres [9] emphasized “the importance of innovation diffusion, as the process of new products, service market penetration that is empowered by social influences”. Many innovation studies focus on manufacturing firms [10][11][12][13][14][15][16].

However, researchers are also interested in service sector innovation [17][18][19][20][21]. Nevertheless, it must be noted that there are difficulties in measuring innovation because of the intangibility, interactivity, inseparability and variability of services [22][23]. For the above reasons, human resources (employees’ skills, abilities and experiences), organization of the innovation process, innovation outputs (service innovations can be adopted from competitors easily, so innovations must be constantly developed), communications technology (ICT) and intangibility information are the most important technologies for the service sector.

2. Innovation in the Tourism Industry

Innovation is a tool for achieving economic success, environmental sustainability and competitiveness. Thus, tourism firms should innovate constantly. It is also mentioned that innovation in tourism is quite valuable in creating a sustainable advantage for tourism destinations over other destinations [24][25][26], due to the speed with which competitors can copy successful ideas. Therefore, it is necessary that innovations be difficult for competitors to adopt. In the field of tourism, the types of innovations proposed by Abernathy and Clark [27] are

- regular, which includes investing to increase productivity and training personnel to be more efficient in order to raise standards and quality;

- niche, including firms taking advantage of business opportunities, increasing their network in the market and developing new products by combining existing ones;

- revolutionary, involving applying new technologies in order to implement new methods in the market;

- architectural, aiming to develop new attractions and events and transferring the use of new research-based knowledge, including processes performed in the most optimal way.

- Later, Hjalager [28] presented five types of innovation, which are

- product or service innovations: these include changes that can be noticed easily by customers (or tourists). They may be something “new” that they have not seen before or just new for the specific enterprise or at a particular destination;

- process innovations: these are changes that aim to improve the levels of efficiency and productivity or technology in a company;

- managerial innovations: these concern new ways of organizing business processes, compensating exemplary work with financial or non-financial benefits, empowering staff and improving employee satisfaction. Applying practices that retain employees are extremely beneficial in the tourism industry, as it is highly labor sensitive;

- marketing innovations: these include new marketing concepts, such as co-production of brands and loyalty programs;

- institutional innovations: these are new forms of co-operation and organizational structure, such as alliances, networks and clusters.

However, it is hard to differentiate among the previous types of innovation (product/service, process, managerial, institutional and marketing innovations), since there is a close relationship among them. For instance, a firm that needs to develop changes in marketing without technology investments (which belong to the process innovation) is impossible.

3. Managerial Innovations in the Tourism Industry

Managerial innovations play a meaningful role in increasing the effectiveness and competitiveness of firms to generate economic growth [30]. They provide a firm the capability to improve its structure, to adopt new managerial ideas and processes, to enable strategic renewal and to promote organizational change. Tourism organizations can easily imitate the most valuable innovations among them [31]; however, management innovation is difficult to replicate and challenging to imitate due to its organization-specific nature [32]. Hence, this kind of innovation assists companies to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage and increase competitiveness [33][34].

In particular, managerial innovations are “new organizational structures, management practices, administrative systems, processes and techniques that could create value for the organization” [35][36]. Types of this innovation include total quality management (TQM), quality circle, just-in-time production and 360-degree feedback [37]. Increasing attention is being paid to the crucial role of managerial innovation in developing strategies for increasing economic growth, organizational performance and adopting organizational changes [31][38].

The main factors that influence a firm’s ability to manage innovation are management style/leadership, organizational structure, corporate strategy, technology, knowledge management, employees and innovation processes [8]. By analyzing these elements, it can be able to understand the important role of each factor that affects the competitiveness of a company and especially those in the tourism industry.

Among various leadership approaches, it seems that empowering leadership is the most efficient, since it emphasizes employees, enhances participation in decision making, eliminates bureaucratic restrictions, and cultivates a climate of creativity that gives employees the chance to take initiative, express new ideas and find efficient ways to face the daily challenges in their workplace. This attitude encourages the flexibility to change and provide employees with the necessary resources for innovation [39][40][41][42][43]. However, empowering leadership is also related positively to several outcomes, such as sales performance, work effort [44], self-leadership [45] and employee creativity [46].

Considering this context, leaders seem to play the main role in devising and implementing management innovations in a company in order to maintain a competitive advantage over its competitors [47]. Several firms in the tourism sector need employees to creatively perform their job to upgrade service quality and maintain long-term survival [48][49][50]. Thus, managers need to apply the proper type of leadership as an effective tool to implement innovation by providing adequate resources and support to employees to make necessary changes, including recognizing and rewarding their creative behaviors.

Organizational structure is “the framework of the relations on jobs, systems, operating process, people and groups making efforts to achieve the goals” [35]. Organizational structure is a set of methods dividing a task into determined duties and coordinating them. It includes models of internal relations of organization, responsibility and decision-making delegation as well as formal communication channels. Improving the information flow is one more facility provided by the structure of the organization. Organizational structure should alleviate decision making, proper reaction to environments and conflict resolution between the departments of a firm. The relationship between the main principles of a firm and coordination across its activities and internal organizational relations in terms of reporting is an element of organizational structure [35][38][51]

Corporate strategy is the scope and the direction of an organization in the long term, which achieves advantage in a changing environment through its configuration of competences and resources, with the aim of fulfilling the expectations of stakeholders [52]. Hence, a tourism firm’s strategy should promote and support innovation inside the firm, as it can support it to maintain its competitive advantage in the market, while at the same time make it more flexible to find efficient solutions to face the constant changes that arise from the external environment in which it operates. Technology can be defined at different levels [53]. Technological innovation involves the generation and adoption of a new idea concerning physical equipment, techniques/systems or tools that extend a firm’s capabilities into production systems and operational processes [53][54][55]. For instance, ICT, social media, mobile and smart phones and websites, as well as multimedia, virtual and augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and several other technological advances, especially in tourism, have helped speed up operations and have transformed the traveling process into a much more enjoyable and efficient experience.

Knowledge management is concerned with obtaining and communicating information and ideas that underline innovation competencies and include idea generation. It also covers the implicit and explicit knowledge of an organization [56][57][58] as well as the processes of gathering and using information. This is important for every firm and especially for a tourism firm, where changes are more intense and quicker. Thus, information is precious for a tourism firm, so as to be aware of such changes and to know how to act in order to maintain its privilege.

Employees and innovation processes concern the way that a firm behaves towards its employees in order for them to be satisfied and to improve their performance. In the case that the work environment enhances creativity and allows for employees to be satisfied and feel comfortable and secure to express their ideas, worries and thoughts and on the grounds that they are provided with the adequate resources, employees can be more creative, and this can lead to innovations for the company [50][59][60]. This factor is also important for tourism companies, since they mainly hire seasonal employees who are aware of the fact that they will work for a specific period of the year and that there are not many opportunities to advance in a tourism firm. This may deter them from feeling willing and motivated to do the best job that they can so as to enhance organizational performance. For these reasons, following management of employees in a tourism firm is of major importance.

Some elements that pertain to innovation as an outcome for a tourism company are form, magnitude, referent and type. More precisely, form is differentiated into service or product innovation, business model innovation and process innovation. Service or product innovation concerns a new service facility or a new product for the company [61], the customers or the market [62]. Process innovation concerns the “introduction of new management approaches, new production methods and new technologies that can be used to improve management processes and production” [62]. Business model innovation determines how a company creates and delivers value to its customers, whether it is new to the firm, customer or industry.

Magnitude indicates the degree of newness of the innovation outcome with respect to the referent [63]. Radical innovation includes fundamental changes, whereas incremental innovation represents variations in the existing practices and routines [64]. Both types of innovation are important for a tourism firm, as they help it to be more operational.

Referent defines the newness of innovation as an outcome. It can be new to the firm, to the market it serves, or to the industry. In terms of type, it can be distinguished administrative and technical innovations. Administrative innovations are indirectly related to the basic work activity and more directly related to its managerial aspects, such as human resources, organizational structure, administrative processes and so on. Conversely, technical innovations include the products, processes and technologies that are used to produce products or render services related directly to the basic work activity of an organization.

Thus, the role of innovation as an outcome is essential for successful exploitation of an idea in order to improve the performance of a tourism firm. Consequently, one way for the firms to increase “quality” in the tourism sector is via managerial innovations, which lead to increased organizational performance [65][66][67][68].

Likewise, the broader elements of the tourism sector, such as restaurants, hotels, travel agencies, tourist shops, promotion/advertising agencies, transportation companies and any other kind of firm whose operation is related to the tourism sector, that aim to innovate tend to increase the possibilities to enhance their firm growth [69] and productivity [70].

Apart from these, innovation is also influenced by external and internal environmental factors [71][72], size, leadership characteristics, professionalism and entrepreneurial characteristics [73], management attitudes [74], the level of e-commerce business [75], the ability of entrepreneurs [76], the adoption and use of ICT [77], the customer relation management system, the capability of building relationships and partnerships with customers and suppliers [78] and cooperation with firms that hold the leading position in the market [79]. There are many advantages for a firm, especially in the tourism sector, to be member of a network. A network may include customers, suppliers, firms, authorities and academics.

Cooperation among the members of a network can lead to the development of ideas that can in turn improve creativity and result in the implementation of innovations. These partners contribute to the innovation process. This can influence the competitiveness of the tourism industry, since networks are incubators of innovative ideas and new businesses [80]. Through networks, scientific knowledge is transferred, and consequently, innovation can be improved and fostered [81]. The ability to absorb external knowledge is a key factor in developing competitive and original innovations [81].

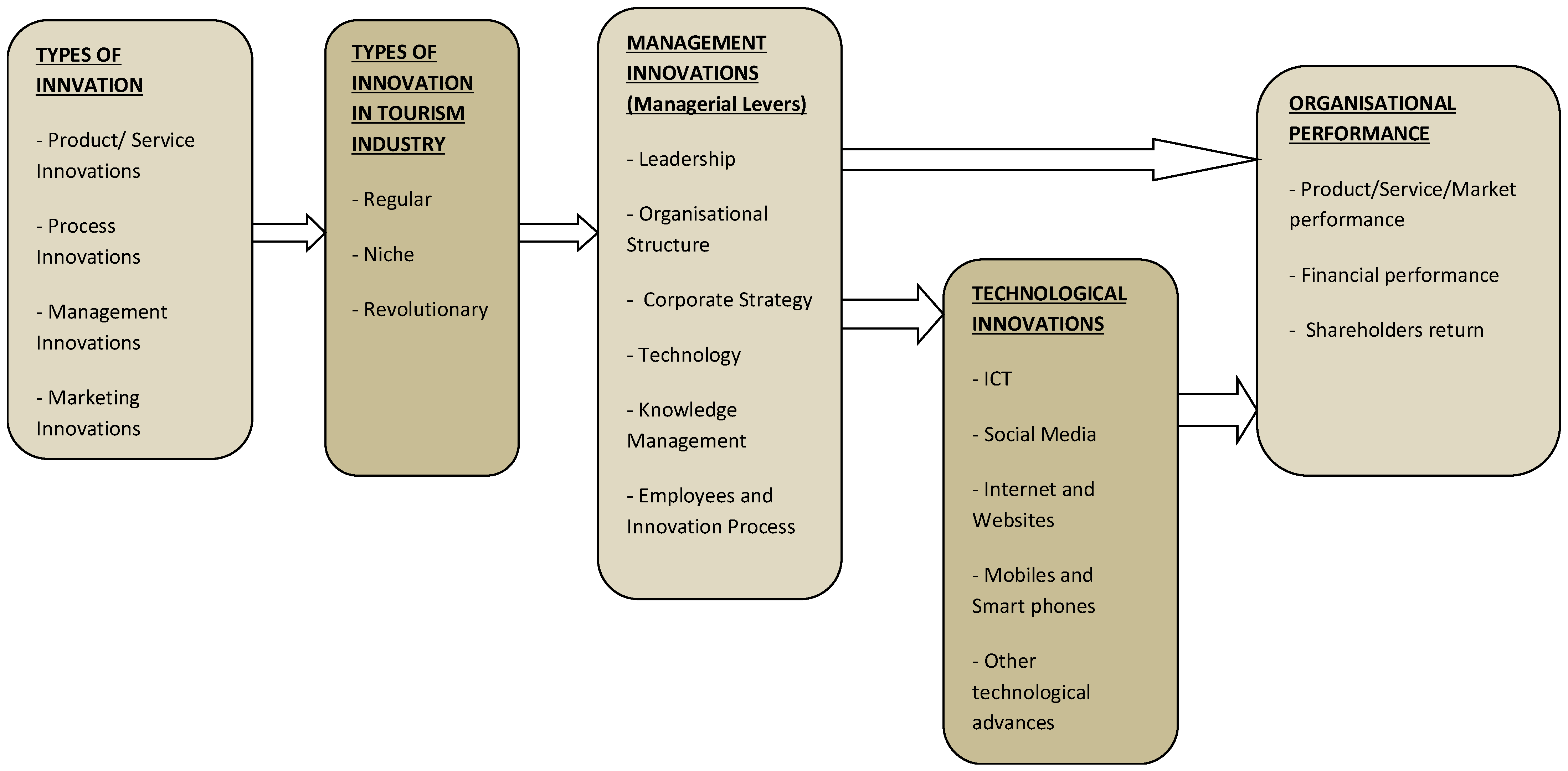

The role and the importance of the relationship among innovation, innovation in the tourism industry, management innovation and technological innovations are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The framework of the links among innovation, innovation in the tourism industry, management innovation, technological innovations and organizational performance.

Figure 1 shows the links among different types of innovations, and especially management and technological innovations, which lead to an increase in organizational performance. Organizational performance encompasses three areas: financial performance, product/service or market performance and shareholder return [82][83].

The first area of financial performance describes the economic statement of the firm as profits, return on investments, return on assets and so on. The second area of product/service market performance includes the market share of the firm. The last area of shareholder return concerns the total shareholder return, the economic value added and others. There are different ways (or variables) to measure organizational performance [84].

In addition, it must be mentioned that according to the size of the firm, its strategy, its goals, its capabilities, its needs, its budget and the market that it operates in, among other criteria, every company is able to adopt different types of innovation in order to improve its performance [85]. For instance, technological innovations are necessary, especially in tourism. Hence, further analysis of this element is provided in the following section.

References

- Dess, G.G.; Picken, J.C. Changing roles: Leadership in the 21st century. Organ. Dyn. 2000, 28, 18–33.

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A. Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 8–30.

- Mone, M.A.; McKinley, W.; Barker, V.L. Organization decline and innovation: A contingency framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 115–132.

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934.

- European Commission. Green Paper on Innovation. Document Drawn up on the Basis of COM(95) 688 Final, Bulletin of the European Union Supplement 5/95; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2009.

- Hansen, S.O.; Wakonen, J. Innovation, a winning solution? Int. J. Technol. Manag. 1997, 13, 345–358.

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantages of Nation; Macmillan Press: London, UK, 1990.

- Smith, M.; Busi, M.; Ball, P.; Van der Meer, R. Factors influencing and organization’s ability to manage innovation: A structured literature review and conceptual model. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2008, 12, 655–676.

- Peres, R.; Muller, E.; Mahajan, V. Innovation diffusion and new product growth models: A critical review and research directions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 91–106.

- Cucculelli, M.; Ermini, B. Risk attitude, product innovation, and firm growth. Evidence from Italian manufacturing firms. Econ. Lett. 2013, 118, 275–279.

- De Vries, E.J. Innovation in services in networks of organizations and in the distribution of services. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 1037–1051.

- Laperche, B.; Picard, F. Environmental constraints, product-service systems development and impacts on innovation management: Learning from manufacturing firms in the French context. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 118–128.

- Sanchez-Sellero, P.; Rosell-Martinez, J.; Garcia-Vazquez, J.M. Innovation as a driver of absorptive capacity from foreign direct investment in Spanish manufacturing firms. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 75, 236–245.

- Tiron Tudor, A.; Zaharie, M.; Osoian, C. Innovation development needs in manufacturing companies. Procedia Technol. 2014, 12, 505–510.

- Toivonen, M.; Tuominen, T. Emergence of innovations in services. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 887–902.

- Triguero, A.; Corcoles, D. Understanding innovation: An analysis of persistence for Spanish manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 340–352.

- Chang, S.; Gong, Y.; Shum, C. Promoting innovation in hospitality companies through human resource management practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 30, 812–818.

- Desmarchelier, B.; Djellal, F.; Gallouj, F. Environmental policies and eco-innovations by service firms: An agent-based model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 1395–1408.

- Hogan, S.J.; Soutar, G.N.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Sweeney, J.C. Reconceptualizing professional service firm innovation capability: Scale development. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1264–1273.

- O’Cass, A.; Sok, P. Exploring innovation driven value creation in B2B service firms: The roles of the manager, employees, and customers in value creation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1074–1084.

- Thakur, R.; Hale, D. Service innovation: A comparative study of US and Indian service firms. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1108–1123.

- Miller, G.; Twining-Ward, L. Monitoring for a Sustainable Tourism Transition. The Challenge of Developing & Using Indicators; Cabi: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005.

- Howells, J. Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Res. Policy 2007, 35, 715–728.

- Hjalager, A.M. Repairing innovation defectiveness in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 465–474.

- Ritchie, J.R.; Crouch, G.I. The competitive destination: A sustainability perspective. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 1–7.

- Volo, S. Tourism Destination Innovativeness. In Proceedings of the 55th AIEST Congress, Brainerd, MN, USA, 28 August–1 September 2005; Keller, P., Bieger, T., Eds.; pp. 199–211.

- Abernathy, W.J.; Clark, K.B. Innovation: Mapping the winds of creative destruction. Res. Policy 1985, 14, 3–22.

- Hjalager, A.M. A review of innovation research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 1–12.

- Bouranta, N.; Psomas, E.L.; Pantouvakis, A. Identifying the critical determinants of TQM and their impact on company performance: Evidence from the hotel industry of Greece. TQM J. 2017, 29, 147–166.

- Sanidas, E. Organizational Innovations and Economic Growth: Organosis and Growth of Firms, Sectors, and Countries; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005.

- Birkinshaw, J.; Mol, M.J. How management innovation happens. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2006, 47, 81–88.

- Ansari, S.M.; Fiss, P.C.; Zajac, E.J. Made to fit: How practices vary as they diffuse. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 67–92.

- Park, K.J.; Yoo, Y. Improvement of competitiveness in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2017, 33, 173–194.

- Mol, M.J.; Birkinshaw, J. Giant Steps in Management: Innovations That Change the Way We Work; FT Prentice Hall: Dorchester, The Netherlands, 2008.

- Birkinshaw, J.; Hamel, G.; Mol, M.J. Management innovation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 825–845.

- Kimberly, J.R.; Evanisko, M. Organizational innovation: The influence of individual, organizational and contextual factors on hospital adoption of technological and administrative innovations. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 689–713.

- Damanpour, F.; Aravind, D. Managerial innovation: Conceptions, processes, and antecedents. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2012, 8, 423–454.

- Hamel, G. The why, what, and how of management innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 72–84.

- Kim, S.; Yoon, G. An innovation-driven culture in local government: Do senior manager’s transformational leadership and the climate for creativity matter? Public Person. Manag. 2015, 44, 147–168.

- Volberda, H.W.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Heij, C.V. Management innovation: Management as fertile ground for innovation. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 1–15.

- Pieterse, A.N.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.; Stam, D. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 609–623.

- Sarros, J.C.; Cooper, B.K.; Santora, J.C. Building a climate for innovation through transformational leadership and organizational culture. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 145–158.

- Vaccaro, I.G.; Jansen, J.J.P.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Management innovation and leadership: The moderating role of organizational size. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 28–51.

- Amundsen, S.; Martinsen, Ø.L. Empowering leadership: Construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a newscale. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 487–511.

- Tekleab, A.G.; Sims, H.P., Jr.; Yun, S.; Tesluk, P.E.; Cox, J. Are we on the same page? Effects of self-awareness of empowering and transformational leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 14, 185–201.

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128.

- Denti, L.; Hemlin, S. Leadership and innovation in organizations: A systematic review of factors that mediate or moderate the relationship. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 16, 1–20.

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Beesley, L.G. Investigating linkages between creativity and intention to quit: An occupational study of chefs. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 765–776.

- Tag-Eldeen, A.; El-Said, O. Implementation of internal marketing on a sample of Egyptian five-star hotels. Anatolia 2011, 22, 153–167.

- Hon, A.H.Y.; Lui, S.S. Employee creativity and innovation in organizations: Review, integration, and future directions for hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 862–885.

- Hamel, G. The Future of Management; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007.

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A multidimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191.

- Damanpour, F.; Evan, W.M. Organizational innovation and performance: The problem of organizational lag. Adm. Sci. Q. 1987, 29, 392–409.

- Evan, W.M. Organizational lag. Hum. Organ. 1966, 25, 51–53.

- Damanpour, F.; Schneider, M. Characteristics of innovation and innovation adoption in public organizations: Assessing the role of managers. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 19, 495–522.

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–339.

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995.

- Quintane, E.; Mitch Casselman, R.; Sebastian Reiche, B.; Nylund, P.A. Innovation as a knowledge-based outcome. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 928–947.

- Nieves, J.; Diaz-Meneses, G. Antecedents and outcomes of marketing innovation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1554–1576.

- Maier, A.; Brad, S.; Dorin, M.; Nicoara, D.; Maier, D. Innovation by developing human resources, ensuring the competitiveness and success of the organization business processes performances improvement through integrated management of complex projects View project Redesign the security fences of robotic cells. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 645–648.

- Davila, T.; Epstein, M.J.; Shelton, R.D. The Creative Enterprise: Managing Innovative Organizations and People; Greenwood Publishing Group: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2006.

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Leveraging knowledge in the innovation and learning process at GKN. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2004, 27, 674–688.

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Damanpour, F. A review of innovation research in economics, sociology and technology management. Omega 1997, 25, 15–28.

- Damanpour, F. Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 555–590.

- Fening, F.A.; Pesakovic, G.; Amaria, P. Relationship between quality management practices and the performance of small and medium sized enterprise in Ghana. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2008, 7, 694–708.

- Brah, S.A.; Wong, J.L.; Rao, B.M. TQM and business performance in the service sector: A Singapore study. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 20, 1293–1312.

- Shenaway, E.E.; Baker, T.; Lemak, D.J. A meta-analysis of the effect of TQM on competitive advantage. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2007, 25, 442–471.

- Arumugam, V.; Ooi, K.-B.; Fong, T.-C. TQM practices and quality management performance—An investigation of their relationship using data from ISO 9001:2000 firms in Malaysia. TQM Mag. 2008, 20, 636–650.

- Petrou, A.; Daskalopoulou, I. Innovation and small firms’ growth prospects: Relational proximity and knowledge dynamics in a low-tech industry. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 1591–1604.

- Blake, A.; Sinclair, M.T.; Soria, J.A.C. Tourism productivity—Evidence from the United Kingdom. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1099–1120.

- El-Gohary, H. Factors affecting E-marketing adoption and implementation in tourism firms: An empirical investigation of Egyptian small tourism organisations. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1256–1269.

- Fernandez, J.I.P.; Cala, A.S.; Domecq, C.F. Critical external factors behind hotels’ investments in innovation and technology in emerging urban destinations. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 339–357.

- Sundbo, J.; Orfila-Sintes, F.; Sorensen, F. The innovative behaviour of tourism firms comparative studies of Denmark and Spain. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 88–106.

- Chan, A.D.; Go, F.M.; Pine, R. Service innovation in Hong Kong: Attitudes and practice. Serv. Ind. J. 1998, 18, 112–124.

- Peng, L.F.; Lai, L.L. A service innovation evaluation framework for tourism e-commerce in China based on BP neural network. Electron. Mark. 2014, 24, 37–46.

- Notaro, S.; Paletto, A.; Piffer, M. Tourism innovation in the forestry sector: Comparative analysis between Auckland region (New Zealand) and Trentino (Italy). iForest-Biogeosci. For. 2012, 5, 262–271.

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.; Llach, J. Adoption and use of technology in small business environments. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 1456–1472.

- Cano, M.; Drummond, S.; Miller, C.; Barclay, S. Learning from others: Benchmarking in diverse tourism enterprises. Total Qual. Manag. 2001, 12, 974–980.

- Ronningen, M. Innovative processes in a nature-based tourism case: The role of a tour-operator as the driver of innovation. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 190–206.

- Malakauskaite, A.; Navickas, V. Relation between the level of clusterization and tourism sector competitiveness. Inz. Ekon.-Eng. Econ. 2010, 21, 60–67.

- Hoarau, H.; Kline, C. Science and industry: Sharing knowledge for innovation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 44–61.

- Adams, P.; Bodas Freitas, I.M.; Fontana, R. Strategic orientation, innovation performance and the moderating influence of marketing management. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 129–140.

- Bhaskar, A.U.; Mishra, B. Exploring relationship between learning organizations dimensions and organizational performance. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2017, 12, 593–609.

- Azar, G.; Ciabuschi, F. Organizational innovation, technological innovation, and export performance: The effects of innovation radicalness and extensiveness. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 324–336.

- Prokop, V.; Stejskal, J. Dierent approaches to managing innovation activities: An analysis of strong, moderate, and modest innovators. Eng. Econ. 2017, 28, 47–55.

More

Information

Subjects:

Economics

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.6K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No