Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marketa Bednarikova | -- | 2413 | 2022-05-24 07:19:46 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 2413 | 2022-05-24 07:48:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Bednarikova, M.; Weinberger, V.; Hausnerova, J.; , .; Minar, L. Schlafen 11. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23271 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Bednarikova M, Weinberger V, Hausnerova J, , Minar L. Schlafen 11. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23271. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Bednarikova, Marketa, Vit Weinberger, Jitka Hausnerova, , Lubos Minar. "Schlafen 11" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23271 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Bednarikova, M., Weinberger, V., Hausnerova, J., , ., & Minar, L. (2022, May 24). Schlafen 11. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23271

Bednarikova, Marketa, et al. "Schlafen 11." Encyclopedia. Web. 24 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

Schlafen 11 (SLFN11), a member of the mammalian Schlafen family of growth regulatory genes first described in 1998, was recently identified to have a casual association with response to a wide range of DDA, including platinum salts and PARPi. Multiple preclinical models and some clinical studies have demonstrated that high SLFN11 expression levels positively correlate with increased DDA sensitivity in various types of cancers.

SLFN11

ovarian cancer

high-grade serous carcinoma

DNA-damaging agents

PARPi

chemoresistance

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the leading cause of death amongst all gynecological cancers, with an overall 5-year survival rate of no more than 35% for advanced stages [1][2]. For decades, primary therapy has consisted of cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy (CT). The leading cause of the high mortality rate, besides the diagnosis at an advanced stage, is the sooner or later acquired resistance to systemic therapy despite a good response in the majority of cases initially. Thus, platinum sensitivity or resistance, together with tumor stage, histotype, and the ability of complete surgical resection, represent the main clinically used prognostic factors. Moreover, platinum sensitivity is the key predictive factor for the successful subsequent treatment of recurrent disease [3][4].

Lately, the anti-angiogenic agent bevacizumab, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) have become an integral part of the systemic treatment of primary or relapsed ovarian cancer [5][6][7][8]. Unfortunately, the precise selection of patients with a high probability of a good response to this novel therapy remains far from optimal. Despite the high cost and significant toxicity of bevacizumab, no predictive markers for treatment response have been identified yet. The precise prediction of platinum resistance would help to protect non-responders from an even more aggressive combination with bevacizumab. Similarly, regardless of the known effect of PARPi, especially in ovarian cancer with either a mutation in the BRCA 1/2 genes or a deficiency in the homologous recombination system (HR), even patients with HR-proficient tumors may benefit from PARPi [9]. On top of that, not all BRCA-deficient tumors are sensitive to PARPi [10]. The sensitivity to PARPi has been associated with defects in the DNA damage response. Therefore, the identification of markers predicting sensitivity to platinum compounds belonging to DNA damage-inducing agents (DDA) could also help in this field [11][12].

So far, platinum sensitivity or resistance has been evaluated clinically, based on a platinum-free interval (TFIp), i.e., the time between the last course of platinum-based chemotherapy and the progression of the disease. Despite platinum-sensitivity in the majority of ovarian cancers, there is a significant proportion of patients with primary platinum-refractory or resistant disease (i.e., progressive during or shortly after the termination of primary chemotherapy). In other words, about 30–40% of patients undergo an ineffective initial treatment accompanied by substantial side effects [4][13][14]. Although some genetic alterations are known to be associated with resistance to the platinum-containing regimen, no validated molecular predictive biomarkers capable of predicting response to platinum-based chemotherapy have been identified yet [14][15][16][17].

Schlafen 11 (SLFN11), a member of the mammalian Schlafen family of growth regulatory genes first described in 1998, was recently identified to have a casual association with response to a wide range of DDA, including platinum salts and PARPi. Multiple preclinical models and some clinical studies have demonstrated that high SLFN11 expression levels positively correlate with increased DDA sensitivity in various types of cancers [11][18][19][20][21][22][23]. Conversely, the loss of SLFN11 expression is associated with resistance to these therapeutics [10][24][25]. Independent groups proved that SLFN11 expression in tumor cells could be easily assessed by immunohistochemistry [26][27][28][29]. Altogether, data published so far suggest the promising role of SLFN11 as a predictive biomarker in the clinical setting across multiple cancers [12][30].

2. SLFN11 as a Guardian of the Genome in Response to Replication Stress

In 2012, two independent research groups discovered by bioinformatic analyses of large cancer cell line panels that the nuclear protein SLFN11 is the causal and dominant genomic determinant of response to DNA-damaging agents [10][24]. Further studies confirmed that the nuclear protein SLFN11 plays a crucial role in cell cycle arrest and the induction of apoptosis in response to replication stress and therefore acts as a guardian of the genome. In case of various types of DNA damage caused by anticancer agents, such as covalent DNA adducts formed by platinum compounds or inhibition of DNA repair by PARPi (see Table 1), SLFN11 binds to stressed replication forks and thus blocks replicative helicase complex, induces chromatin opening, and forces the degradation of the key replication factor CD1 [31][32][33][34]. These processes ultimately lead to irreversible cell death.

Table 1. Anticancer agents inducing replication stress (based on [35]).

| DNA-Targeting Agents | Representative Drugs | Target | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkylating agents | Cisplatine Carboplatine Oxaliplatine |

DNA template damage | Inter-strand crosslinks |

| Temozolomide | DNA template damage MGMT |

O6-alkyl-guanine lesions on DNA | |

| TOP I and II inhibitors | Irinotecan Topotecan Etoposide Doxorubicin Mitoxantrone |

DNA template damage | Block the re-ligation of the TOP-DNA cleavage complexes |

| PARP inhibitors | Olaparib Rucaparib Niraparib Talazoparib Veliparib |

DNA template damage by defective single-strand breaks repair | Generating toxic PARP-DNA complexes |

| Nucleoside analogs | Gemcitabine Cytarabine 5-azacytidine |

DNA elongation inhibition | Blocking DNA polymerase or reducing the pool of nucleotides |

Abbreviations: TOP = topoisomerase; PARP = poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid; MGMT = DNA-repair protein O6 methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase.

SLFN11-mediated cell cycle inhibition works independently on the classical signal pathway of ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related and checkpoint kinase 1 (ATR/CHK1) [36][37]. Notably, the effectivity of non-DNA-damaging anticancer drugs acting by a different mechanism (such as microtubules inhibitors, kinase inhibitors, or mTOR inhibitors) is independent of the level of SLFN11 expression [10][24].

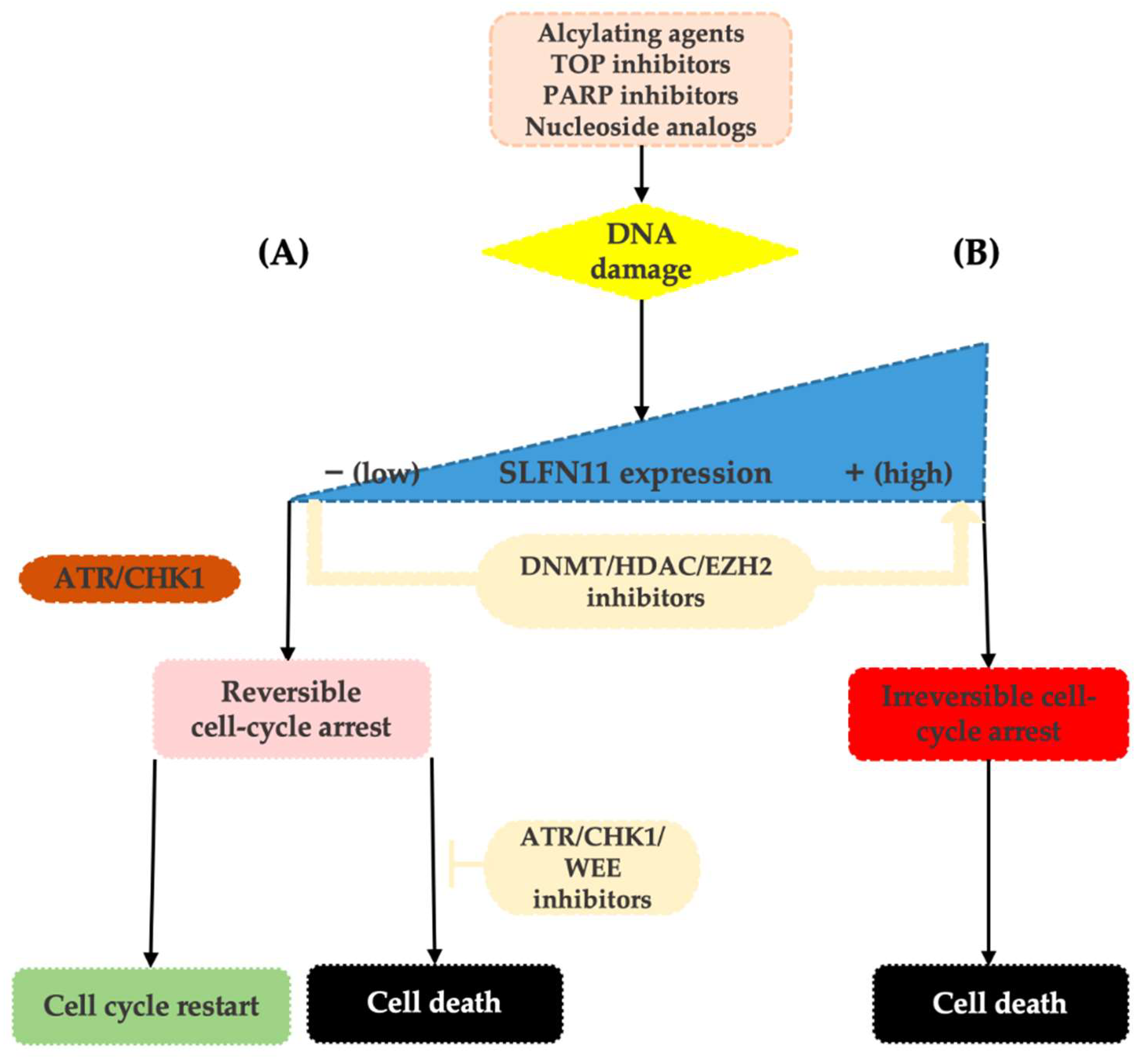

Lack of SLFN11 expression makes the functionality of the SLFN11-mediated system impossible and increases tumor viability. SLFN11-low cancer cells then rely on the ATR/CHK1 DNA repair system that enables only reversible cell-cycle arrest in response to replication stress. Cells are then capable of repairing DNA damage and recover replication, which contributes to resistance to DDA [12][25] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Upon replication stress caused by various types of DDA, SLFN11-proficient cells undergo an enforced G1/S arrest ultimately resulting in cell death (B). On the contrary, SLFN11-deficient cells reliant on the ATR/CHK1 pathway re-enter the cell cycle, slowly progress through the S-phase, and following DNA repair can survive (A). SLFN11 expression can be reactivated by the inhibitors of epigenetic modulators, such as DNA methyltransferase (DNMT), histone deacetylase (HDAC), or EZH2 inhibitors. Resistance of SLFN11-deficient cells can be overcome by combination with ATR/CHK1/WEE1 inhibitors.

Based on detailed analyses of cancer cell lines, neither clinically meaningful SLFN11 mutations nor its copy number variations have been reported. Thus, the current evidence suggests that the expression level of SLFN11 is largely regulated by epigenetic processes such as DNA methylation and histone modifications [36][38][39]. Indeed, in different tumor types, epigenetic modifications have been shown to cause loss of SLFN11 expression and associated resistance to DDA [25][36][39][40][41][42]. These epigenetic processes may also induce dynamic changes in tumor expression levels of SLFN11 during chemotherapy and cause the development of acquired resistance to DDA [23][43][44]. On top of that, as these modifications are reversible, the therapeutic interventions using inhibitors of DNA methylation (such as 5-azacytadine) or histone deacetylases (such as romidepsin or entinostat) may result in the re-increase in SLFN11 tumor expression levels and thus re-sensitization to DDA, making SLFN11 an attractive therapeutic target [25][34][42][43][45][46]. The other way to synergistically overcome the resistance of low SLFN11 tumors to DNA-damaging agents is by using replication checkpoint inhibitors (ATR/CHK1/WEE1 inhibitors), such as berzosertib, ceralasertib, and elimustertib [35] (Figure 1).

3. Clinical Evaluation of SLFN11 Status

Initially, quantification of SLFN11 expression either in cancer cell lines or patient-derived xenografts (PDX) was performed by transcript analyses using Western blotting [10][11][18][24][43]. Subsequently, protein assessment in tumor tissue by immunohistochemistry (IHC) was proven as an acceptable method in various types of cancer [21][26][27][28].

According to the study by Lok et al. on PDX models, SLFN11 IHC scoring seemed to be a stronger predictor of PARPi efficacy than both SLFN11 gene expression and protein expression by Western blot [27]. Subsequently, Takashima et al. demonstrated a substantial discrepancy between SLFN11 expression in tumor samples assessed by IHC and RNA-seq performed in non-microdissected tissue samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) datasets. Levels measured by RNA-seq reflected not only SLFN11 positivity in the cancer cell, but also in the surrounding stromal or inflammatory cells. On the other hand, immunohistochemistry enabled distinctions between positivity in cancer and non-cancer cells. These results indicate a potential of IHC to be of key importance for the precise identification of SLFN11-negative tumors that can be non-responsive to the DNA-damaging agents [29]. Therefore immunohistochemistry, the well-established and widely accepted pathological method, seems to be optimal for the evaluation of SLFN11 expression in patient samples. Undoubtedly the feasibility of immunohistochemical testing for SLFN11 could facilitate the rapid implementation of SLFN11 assessments into clinical practice.

One of the important studies aiming to provide a practical resource for the utility of SLFN11 in clinical practice was published by Takashima et al. They performed a comprehensive analysis of SLFN11 expression in malignant and the adjacent non-tumor tissues across 16 human organs. They compared three commercially available antibodies and proved the mouse D-2 (#sc-515071, Santa Cruz) had the best specificity and sensitivity ratio. They also established a rigid step-by-step protocol and scoring system for evaluating SLFN11 expression by IHC. According to the average values of the ratio of positivity, SLFN11 immunohistochemical scores were considered 1+ (1–10%), 2+ (11–50%), or 3+ (51–100%). Their results demonstrated a broad diversity of SLFN11 expression among organs. They also showed SLFN11 expression to be highly dynamic and very different in non-tumor and tumor tissues. While in some organs, such as colon and prostate, tumor and non-tumor tissues were consistently negative, in other organs there was a tendency for SLFN11 positivity to be higher (breast, uterine corpus, ovary) or lower (lung, glioblastoma, papillary renal cell carcinoma) in tumors compared to non-tumor tissues [29].

As far as experiences with immunohistochemical testing for SLFN11 in ovarian cancer are concerned, in addition to Takashima et al., the results of four other studies have been published so far. Firstly, Velone presented at the SLFN11 monothematic workshop in 2017 the analysis of 75 cases of high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC). As there was no commercial kit available for SLFN11 immunohistochemical testing at that time, they adopted two kits originally commercialized for Western Blot. According to their findings, IHC appeared clean and specific in samples of HGSC. For the evaluation of SLFN11 levels by IHC, they used the histological score (H-score; HS) with values 0–9 calculated based on an evaluation of the staining intensity score (IS) and the distribution score of stained cells (DS). Cases were then considered as “SLFN11 negative” (HS = 0), “SLFN11 low” (HS = 1, 2), “SLFN11 intermediate” (HS = 3, 4), or “SLFN11 high” (HS = 6, 9), see Table 2 [12].

Table 2. Summary of methodologies used for the immunohistochemical analysis of SLFN11 expression in different studies.

| Tumor Origin (n) | Tissue | Antibody | Evaluation | Author [Reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC (261) | FFPE | Abcam; ab121731 | H-score; value 0–6 1 >4.5—high |

Deng [26] |

| HGSC (75) | N/A | N/A | H-score; value 0–9 2 0—negative 1, 2—low 3, 4—intermediate 6, 9—high |

Ballestrero [12] |

| SCLC (12) | PDX | Sigma-Aldrich; HPA023030 | H-score; value 0–300 3 | Stewart [11] |

| SCLC (7) | PDX | Sigma-Aldrich; HPA023030 | H-score; value 0–300 3 low v. high |

Lok [27] |

| SCLC (48) | FFPE | Sigma-Aldrich; HPA023030 | H-score; value 0–300 3 >1—positive |

Pietanza [28] |

| HCC (182/110) | FFPE | Sigma-Aldrich; HPA023030 | H-score 0/+—low ++/+++—high |

Zhou [47] |

| TNBC (40) | PDX | Sigma-Aldrich; HPA023030 | H-score; value 0–300 3 0—negative 1–60—low >60—high |

Coussy [21] |

| ESCC (73) | FFPE | Santa Cruz; #sc-515071 | H-score; value 0–300 3 ≥51—high |

Kagami [48] |

| 16 human adult organs; malignant and adjacent non-tumor tissue (~ 700) | FFPE |

|

IHC scoring system 1+ (1–10%) 2+ (11–50%) 3+ (51–100%) |

Takashima [29] |

| Various cancer types | PDX | Abcam; ab121731 | H-score; value 0–300 3 ≥31—high |

Winkler [46] |

| HGSC (28) | FFPE | Abcam; ab121731 | H-score; value 0–300 3 ≥60—high |

Winkler [49] |

| Pediatric sarcoma (220) | FFPE | Sigma-Aldrich; HPA023030 | H-score; value 0–300 3 0—negative ≥1—positive |

Gartrell [50] |

| Gastric (169) | FFPE | Santa Cruz; #sc-515071 | IHC scoring system >30%—positive |

Takashima [23] |

| Bladder (120) | FFPE | Santa Cruz; #sc-515071 | IHC scoring system >5%—positive |

Taniyama [51] |

| Non-tumor tissue (86) SCLC (124) HGSC (151) |

TMA FFPE |

Merck; MABF248 Abcam; ab121731 Novus; NBP2–57084 |

H-score; value 0–300 3 >122—high >30—high |

Willis [52] |

Abbreviations: n = number of patients/samples, CRC = colorectal cancer, OC = ovarian cancer, HGSC = high-grade serous carcinoma, SCLC = small cell lung cancer, TNBC = triple-negative breast cancer, ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, DX = patient-derived xenograft, FFPE = Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks, TMA = tissue microarray. 1 HS = intensity (0 … none; 1 … weak; 2 … moderate; 3 … strong) + proportion (0 … <25% positive cells; 1 … 25–50%; 2 … 50–75%; 3 … >75%). 2 HS = intensity score (0 … no stain; 1+ … weak; 2+ … moderate; 3+ … intense) × distribution scores (0 ... no stained cells; 1+ … <10%; 2+ … 10–40%; 3+ … >40%). 3 HS = (% of cells 1+) + (% of cells 2+) × 2 + (% of cells 1+) × 3.

Subsequently, two studies by Winkler et al. were published in 2021, both using the same rabbit polyclonal anti-SLFN11 antibody (ab121731; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and H-score calculated using an identical methodology (Table 2). In the first study aiming to provide a comprehensive analysis of the clinical significance of SLFN11 as a predictive biomarker to DDA on a wide range of cancer models, including ovarian cancer, the cutoff of 31 H-score showed a good predictive power [46]. On the other hand, in the second study focused on SLFN11 assessment in cohorts of platinum-sensitive (PS; n = 15) and platinum-resistant (PR; n = 13) ovarian cancer, a H-score cutoff of 60 obtained maximized accuracy in classifying cohorts according to the response to platinum-based chemotherapy. Notably, in this study, SLFN11 transcript levels by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and protein levels in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue by IHC showed a strongly significant correlation (p = 0.0051) [49].

The authors of the study with the largest number of samples were focused on the correlation of SLFN11 tumor levels with the clinical outcomes of patients treated with standard chemotherapy or olaparib maintenance. The whole evaluated cohort of HGSC samples (n = 151) consisted of platinum-resistant resection specimens (n = 7) obtained from Asterand, samples in a tissue microarray (TMA) format from patients (n = 110) treated with olaparib or placebo maintenance in the Study 19 [53], and samples from patients (n = 34) with different responses to first-line paclitaxel-carboplatin (PAC/CBDCA) chemotherapy [17]. To divide samples into the ‘SLFN high’ or ‘SLFN-low’ group, an H-score cutoff of 30 was developed based on expression distribution. Interestingly, that value was substantially different from the cohort of patients with small-cell lung cancer in the same study with a H-score cutoff of 122 [52].

Taken together, when assessing the available data about the immunohistochemical analysis of SLFN11 in tumor tissue, including ovarian cancer, the following important facts have to be pointed out. Different types of antibodies, distinct methodologies for evaluating immunohistochemical staining, and most importantly, different cutoffs for SLFN11 positivity have been used in the studies published so far (see Table 2).

The promising method for allowing SLFN11 expression to be tracked longitudinally in a non-invasive manner during the course of the disease seems to be an assessment on circulating tumor cells, as has been described recently in small cell lung cancer [54][55]. However, the potential use of circulating tumor cells in ovarian cancer for this purpose is still unclear. Since the intraperitoneal spread is considered to be the primary way of metastasis in ovarian cancer, circulating tumor cell research has not been too extensive so far in this field. Moreover, their isolation and detection methods affect the use of circulating tumor cells in ovarian cancer [56][57].

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Cannistra, S.A. Cancer of the Ovary. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2519–2529.

- Colombo, N.; Sessa, C.; du Bois, A.; Ledermann, J.; McCluggage, W.G.; McNeish, I.; Morice, P.; Pignata, S.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Vergote, I.; et al. ESMO–ESGO Consensus Conference Recommendations on Ovarian Cancer: Pathology and Molecular Biology, Early and Advanced Stages, Borderline Tumours and Recurrent Disease†. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 672–705.

- Wilson, M.K.; Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Aoki, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Lorusso, D.; Oza, A.M.; du Bois, A.; Vergote, I.; Reuss, A.; Bacon, M.; et al. Fifth Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference of the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup: Recurrent Disease. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 727–732.

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Hilpert, F.; Weber, B.; Reuss, A.; Poveda, A.; Kristensen, G.; Sorio, R.; Vergote, I.; Witteveen, P.; Bamias, A.; et al. Bevacizumab Combined With Chemotherapy for Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: The AURELIA Open-Label Randomized Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1302–1308.

- Burger, R.A.; Brady, M.F.; Bookman, M.A.; Fleming, G.F.; Monk, B.J.; Huang, H.; Mannel, R.S.; Homesley, H.D.; Fowler, J.; Greer, B.E.; et al. Incorporation of Bevacizumab in the Primary Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2473–2483.

- Oza, A.M.; Cook, A.D.; Pfisterer, J.; Embleton, A.; Ledermann, J.A.; Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Kristensen, G.; Carey, M.S.; Beale, P.; Cervantes, A.; et al. Standard Chemotherapy with or without Bevacizumab for Women with Newly Diagnosed Ovarian Cancer (ICON7): Overall Survival Results of a Phase 3 Randomised Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 928–936.

- Aghajanian, C.; Blank, S.V.; Goff, B.A.; Judson, P.L.; Teneriello, M.G.; Husain, A.; Sovak, M.A.; Yi, J.; Nycum, L.R. OCEANS: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Trial of Chemotherapy With or Without Bevacizumab in Patients With Platinum-Sensitive Recurrent Epithelial Ovarian, Primary Peritoneal, or Fallopian Tube Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2039–2045.

- Colombo, I.; Kurnit, K.C.; Westin, S.N.; Oza, A.M. Moving from Mutation to Actionability. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, 38, 495–503.

- Barretina, J.; Caponigro, G.; Stransky, N.; Venkatesan, K.; Margolin, A.A.; Kim, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Lehár, J.; Kryukov, G.V.; Sonkin, D.; et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Enables Predictive Modelling of Anticancer Drug Sensitivity. Nature 2012, 483, 603–607.

- Stewart, C.A.; Tong, P.; Cardnell, R.J.; Sen, T.; Li, L.; Gay, C.M.; Masrorpour, F.; Fan, Y.; Bara, R.O.; Feng, Y.; et al. Dynamic Variations in Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT), ATM, and SLFN11 Govern Response to PARP Inhibitors and Cisplatin in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28575–28587.

- Ballestrero, A.; Bedognetti, D.; Ferraioli, D.; Franceschelli, P.; Labidi-Galy, S.I.; Leo, E.; Murai, J.; Pommier, Y.; Tsantoulis, P.; Vellone, V.G.; et al. Report on the First SLFN11 Monothematic Workshop: From Function to Role as a Biomarker in Cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 199.

- Colombo, P.-E.; Fabbro, M.; Theillet, C.; Bibeau, F.; Rouanet, P.; Ray-Coquard, I. Sensitivity and Resistance to Treatment in the Primary Management of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2014, 89, 207–216.

- McMullen, M.; Madariaga, A.; Lheureux, S. New Approaches for Targeting Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 77, 167–181.

- The Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group; Patch, A.-M.; Christie, E.L.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; Garsed, D.W.; George, J.; Fereday, S.; Nones, K.; Cowin, P.; Alsop, K.; et al. Whole–Genome Characterization of Chemoresistant Ovarian Cancer. Nature 2015, 521, 489–494.

- Lloyd, K.L.; Cree, I.A.; Savage, R.S. Prediction of Resistance to Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 117.

- Weberpals, J.I.; Pugh, T.J.; Marco-Casanova, P.; Goss, G.D.; Andrews Wright, N.; Rath, P.; Torchia, J.; Fortuna, A.; Jones, G.N.; Roudier, M.P.; et al. Tumor Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Immune Profiling Characterizes Differential Response to First-line Platinum Chemotherapy in High Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 3045–3058.

- Tian, L.; Song, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Xu, J. Schlafen-11 Sensitizes Colorectal Carcinoma Cells to Irinotecan. Anticancer Drugs 2014, 25, 1175–1181.

- Kang, M.H.; Wang, J.; Makena, M.R.; Lee, J.-S.; Paz, N.; Hall, C.P.; Song, M.M.; Calderon, R.I.; Cruz, R.E.; Hindle, A.; et al. Activity of MM-398, Nanoliposomal Irinotecan (Nal-IRI), in Ewing’s Family Tumor Xenografts Is Associated with High Exposure of Tumor to Drug and High SLFN11 Expression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1139–1150.

- Shee, K.; Wells, J.D.; Jiang, A.; Miller, T.W. Integrated Pan-Cancer Gene Expression and Drug Sensitivity Analysis Reveals SLFN11 MRNA as a Solid Tumor Biomarker Predictive of Sensitivity to DNA-Damaging Chemotherapy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224267.

- Coussy, F.; El-Botty, R.; Château-Joubert, S.; Dahmani, A.; Montaudon, E.; Leboucher, S.; Morisset, L.; Painsec, P.; Sourd, L.; Huguet, L.; et al. BRCAness, SLFN11, and RB1 Loss Predict Response to Topoisomerase I Inhibitors in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax2625.

- Rathkey, D.; Khanal, M.; Murai, J.; Zhang, J.; Sengupta, M.; Jiang, Q.; Morrow, B.; Evans, C.N.; Chari, R.; Fetsch, P.; et al. Sensitivity of Mesothelioma Cells to PARP Inhibitors Is Not Dependent on BAP1 but Is Enhanced by Temozolomide in Cells with High-Schlafen 11 and Low-O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase Expression. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 843–859.

- Takashima, T.; Taniyama, D.; Sakamoto, N.; Yasumoto, M.; Asai, R.; Hattori, T.; Honma, R.; Thang, P.Q.; Ukai, S.; Maruyama, R.; et al. Schlafen 11 Predicts Response to Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Gastric Cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 65–77.

- Zoppoli, G.; Regairaz, M.; Leo, E.; Reinhold, W.C.; Varma, S.; Ballestrero, A.; Doroshow, J.H.; Pommier, Y. Putative DNA/RNA Helicase Schlafen-11 (SLFN11) Sensitizes Cancer Cells to DNA-Damaging Agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15030–15035.

- Nogales, V.; Reinhold, W.C.; Varma, S.; Martinez-Cardus, A.; Moutinho, C.; Moran, S.; Heyn, H.; Sebio, A.; Barnadas, A.; Pommier, Y.; et al. Epigenetic Inactivation of the Putative DNA/RNA Helicase SLFN11 in Human Cancer Confers Resistance to Platinum Drugs. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3084–3097.

- Deng, Y.; Cai, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, X.; Wang, J. High SLFN11 Expression Predicts Better Survival for Patients with KRAS Exon 2 Wild Type Colorectal Cancer after Treated with Adjuvant Oxaliplatin-Based Treatment. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 833.

- Lok, B.H.; Gardner, E.E.; Schneeberger, V.E.; Ni, A.; Desmeules, P.; Rekhtman, N.; de Stanchina, E.; Teicher, B.A.; Riaz, N.; Powell, S.N.; et al. PARP Inhibitor Activity Correlates with SLFN11 Expression and Demonstrates Synergy with Temozolomide in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 523–535.

- Pietanza, M.C.; Waqar, S.N.; Krug, L.M.; Dowlati, A.; Hann, C.L.; Chiappori, A.; Owonikoko, T.K.; Woo, K.M.; Cardnell, R.J.; Fujimoto, J.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Study of Temozolomide in Combination with Either Veliparib or Placebo in Patients with Relapsed-Sensitive or Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2386–2394.

- Takashima, T.; Sakamoto, N.; Murai, J.; Taniyama, D.; Honma, R.; Ukai, S.; Maruyama, R.; Kuraoka, K.; Rajapakse, V.N.; Pommier, Y.; et al. Immunohistochemical Analysis of SLFN11 Expression Uncovers Potential Non-Responders to DNA-Damaging Agents Overlooked by Tissue RNA-Seq. Virchows Arch. 2021, 478, 569–579.

- Zhang, B.; Ramkumar, K.; Cardnell, R.J.; Gay, C.M.; Stewart, C.A.; Wang, W.-L.; Fujimoto, J.; Wistuba, I.I.; Byers, L.A. A Wake-up Call for Cancer DNA Damage: The Role of Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) across Multiple Cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 1333–1340.

- Aladjem, M.I.; Redon, C.E. Order from Clutter: Selective Interactions at Mammalian Replication Origins. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 101–116.

- Murai, J.; Tang, S.-W.; Leo, E.; Baechler, S.A.; Redon, C.E.; Zhang, H.; Al Abo, M.; Rajapakse, V.N.; Nakamura, E.; Jenkins, L.M.M.; et al. SLFN11 Blocks Stressed Replication Forks Independently of ATR. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 371–384.

- Mu, Y.; Lou, J.; Srivastava, M.; Zhao, B.; Feng, X.-H.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Huang, J. SLFN11 Inhibits Checkpoint Maintenance and Homologous Recombination Repair. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 94–109.

- Jo, U.; Murai, Y.; Chakka, S.; Chen, L.; Cheng, K.; Murai, J.; Saha, L.K.; Miller Jenkins, L.M.; Pommier, Y. SLFN11 Promotes CDT1 Degradation by CUL4 in Response to Replicative DNA Damage, While Its Absence Leads to Synthetic Lethality with ATR/CHK1 Inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2015654118.

- Jo, U.; Murai, Y.; Takebe, N.; Thomas, A.; Pommier, Y. Precision Oncology with Drugs Targeting the Replication Stress, ATR, and Schlafen 11. Cancers 2021, 13, 4601.

- Murai, J.; Thomas, A.; Miettinen, M.; Pommier, Y. Schlafen 11 (SLFN11), a Restriction Factor for Replicative Stress Induced by DNA-Targeting Anti-Cancer Therapies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 201, 94–102.

- Forment, J.V.; O’Connor, M.J. Targeting the Replication Stress Response in Cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 188, 155–167.

- Rajapakse, V.N.; Luna, A.; Yamade, M.; Loman, L.; Varma, S.; Sunshine, M.; Iorio, F.; Sousa, F.G.; Elloumi, F.; Aladjem, M.I.; et al. CellMinerCDB for Integrative Cross-Database Genomics and Pharmacogenomics Analyses of Cancer Cell Lines. iScience 2018, 10, 247–264.

- Moribe, F.; Nishikori, M.; Takashima, T.; Taniyama, D.; Onishi, N.; Arima, H.; Sasanuma, H.; Akagawa, R.; Elloumi, F.; Takeda, S.; et al. Epigenetic Suppression of SLFN11 in Germinal Center B-Cells during B-Cell Development. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0237554.

- Reinhold, W.C.; Thomas, A.; Pommier, Y. DNA-Targeted Precision Medicine; Have We Been Caught Sleeping? Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 2–6.

- Reinhold, W.C.; Varma, S.; Sunshine, M.; Rajapakse, V.; Luna, A.; Kohn, K.W.; Stevenson, H.; Wang, Y.; Heyn, H.; Nogales, V.; et al. The NCI-60 Methylome and Its Integration into CellMiner. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 601–612.

- Tang, S.-W.; Thomas, A.; Murai, J.; Trepel, J.B.; Bates, S.E.; Rajapakse, V.N.; Pommier, Y. Overcoming Resistance to DNA-Targeted Agents by Epigenetic Activation of Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) Expression with Class I Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1944–1953.

- Gardner, E.E.; Lok, B.H.; Schneeberger, V.E.; Desmeules, P.; Miles, L.A.; Arnold, P.K.; Ni, A.; Khodos, I.; de Stanchina, E.; Nguyen, T.; et al. Chemosensitive Relapse in Small Cell Lung Cancer Proceeds through an EZH2-SLFN11 Axis. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 286–299.

- Lheureux, S.; Oaknin, A.; Garg, S.; Bruce, J.P.; Madariaga, A.; Dhani, N.C.; Bowering, V.; White, J.; Accardi, S.; Tan, Q.; et al. EVOLVE: A Multicenter Open-Label Single-Arm Clinical and Translational Phase II Trial of Cediranib Plus Olaparib for Ovarian Cancer after PARP Inhibition Progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 4206–4215.

- Murai, J.; Feng, Y.; Yu, G.K.; Ru, Y.; Tang, S.-W.; Shen, Y.; Pommier, Y. Resistance to PARP Inhibitors by SLFN11 Inactivation Can Be Overcome by ATR Inhibition. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 76534–76550.

- Winkler, C.; Armenia, J.; Jones, G.N.; Tobalina, L.; Sale, M.J.; Petreus, T.; Baird, T.; Serra, V.; Wang, A.T.; Lau, A.; et al. SLFN11 Informs on Standard of Care and Novel Treatments in a Wide Range of Cancer Models. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 951–962.

- Zhou, C.; Liu, C.; Liu, W.; Chen, W.; Yin, Y.; Li, C.-W.; Hsu, J.L.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Q.; Li, H.; et al. SLFN11 Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumorigenesis and Metastasis by Targeting RPS4X via MTOR Pathway. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4627–4643.

- Kagami, T.; Yamade, M.; Suzuki, T.; Uotani, T.; Tani, S.; Hamaya, Y.; Iwaizumi, M.; Osawa, S.; Sugimoto, K.; Miyajima, H.; et al. The First Evidence for SLFN11 Expression as an Independent Prognostic Factor for Patients with Esophageal Cancer after Chemoradiotherapy. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1123.

- Winkler, C.; King, M.; Berthe, J.; Ferraioli, D.; Garuti, A.; Grillo, F.; Rodriguez-Canales, J.; Ferrando, L.; Chopin, N.; Ray-Coquard, I.; et al. SLFN11 Captures Cancer-Immunity Interactions Associated with Platinum Sensitivity in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e146098.

- Gartrell, J.; Mellado-Largarde, M.; Clay, M.R.; Bahrami, A.; Sahr, N.A.; Sykes, A.; Blankenship, K.; Hoffmann, L.; Xie, J.; Cho, H.P.; et al. SLFN11 Is Widely Expressed in Pediatric Sarcoma and Induces Variable Sensitization to Replicative Stress Caused By DNA-Damaging Agents. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 2151–2165.

- Taniyama, D.; Sakamoto, N.; Takashima, T.; Takeda, M.; Pham, Q.T.; Ukai, S.; Maruyama, R.; Harada, K.; Babasaki, T.; Sekino, Y.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Schlafen 11 in Bladder Cancer Patients Treated with Platinum-based Chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 784–795.

- Willis, S.E.; Winkler, C.; Roudier, M.P.; Baird, T.; Marco-Casanova, P.; Jones, E.V.; Rowe, P.; Rodriguez-Canales, J.; Angell, H.K.; Ng, F.S.L.; et al. Retrospective Analysis of Schlafen11 (SLFN11) to Predict the Outcomes to Therapies Affecting the DNA Damage Response. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 1666–1676.

- Ledermann, J.; Harter, P.; Gourley, C.; Friedlander, M.; Vergote, I.; Rustin, G.; Scott, C.; Meier, W.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Safra, T.; et al. Olaparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive Relapsed Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1382–1392.

- Byers, L.A.; Stewart, A.; Gay, C.; Heymach, J.; Fernandez, L.; Lu, D.; Rich, R.; Chu, L.; Wang, Y.; Dittamore, R. Abstract 2215: SLFN11 and EZH2 Protein Expression and Localization in Circulating Tumor Cells to Predict Response or Resistance to DNA Damaging Therapies in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 2215.

- Zhang, B.; Stewart, C.A.; Gay, C.M.; Wang, Q.; Cardnell, R.; Fujimoto, J.; Fernandez, L.; Jendrisak, A.; Gilbertson, C.; Schonhoft, J.; et al. Abstract 384: Detection of DNA Replication Blocker SLFN11 in Tumor Tissue and Circulating Tumor Cells to Predict Platinum Response in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 384.

- Van Berckelaer, C.; Brouwers, A.J.; Peeters, D.J.E.; Tjalma, W.; Trinh, X.B.; van Dam, P.A. Current and Future Role of Circulating Tumor Cells in Patients with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. EJSO 2016, 42, 1772–1779.

- Holcakova, J.; Bartosik, M.; Anton, M.; Minar, L.; Hausnerova, J.; Bednarikova, M.; Weinberger, V.; Hrstka, R. New Trends in the Detection of Gynecological Precancerous Lesions and Early-Stage Cancers. Cancers 2021, 13, 6339.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

816

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No