Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Li, H.; Wang, H.; , .; Ding, Y.; Zhang, L. Chinese Wine Industry. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22991 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Li H, Wang H, , Ding Y, Zhang L. Chinese Wine Industry. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22991. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Li, Hua, Hua Wang, , Yinting Ding, Liang Zhang. "Chinese Wine Industry" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22991 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Li, H., Wang, H., , ., Ding, Y., & Zhang, L. (2022, May 17). Chinese Wine Industry. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22991

Li, Hua, et al. "Chinese Wine Industry." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

After more than 40 years of development, China’s wine regulatory system has been constantly improved, from half-base wine standards to pure-juice fermented wine standards, and then to the establishment of a relatively complete and mature industry-standard system with product and manufacturing standards as the core and other relevant industry standards as accessories. This advancement supports that the Chinese wine industry has emerged from New World wine countries. Nowadays, according to statistics from the International Organization of Vine and Wine, China is one of the top grape producers, wine consumers, and importers globally.

Chinese wine

development status

wine regulations

1. Introduction

Although grape cultivation and wine production have a history of several thousand years in China [1], since the beginning of the industrial revolution in the West, the Chinese wine industry has consistently been lagging behind the level of more advanced wine producers [2]. From 1978 to 2013, the Chinese wine industry experienced three stages: beginning, development, and rapid ascent [3][4]. Meanwhile, the legal supervision system of Chinese wine has also made three significant adjustments. The promulgation and implementation of new standards each time have played a considerable role in promoting the development of the wine industry [2].

From 1978 to 1994, with the beginning of a historical process of China’s reform and opening up to the international market, the Chinese wine industry entered a first regulatory phase. At first, there was no uniform standard for winemaking, and manufacturers just implemented their enterprise standards separately. It was not until 1984 that the former Ministry of Light Industry enacted the first Chinese wine standard, Wine and its testing methods (QB 921-1984), which marked a shift in the Chinese wine industry, the first step from disorder to standardization. However, due to the loose requirements set in this standard (dosage of grape juice between 30 and 70%) and its weak legal binding force, inferior quality wines flooded the market seriously damaging the reputation of domestic wines [2].

The years from 1994 to 2004 saw a significant development for the Chinese wine industry, as the winemaking technology gradually changed to pure-juice fermentation. In 1994, Wine (GB/T 15037-1994), the Half base wine (QB/T 1980–1994), and Vitis amurensis wines (QB/T 1982–1994) were promulgated, while Wine and its testing methods (QB 921-1984) was abolished [2]. Wine (GB/T 15037-1994), the first Chinese national standard for pure-juice fermented wine, played an essential role in this stage. Since then, product definitions and testing indexes were consistent with international standards. However, half-base wine still absorbed a particular share of the Chinese market because of the shortage of raw material supply, domestic consumer preference, and low consumption level, until 17 March 2003 when Half base wine (QB/T 1980–1994) was abrogated. On 1 January of the same year, Technical Specification for Grape Wine Making in China was put into effect. This important guiding document draws on international winemaking regulations and adapts them to China’s wine production conditions. Besides, the old edition of Wine (GB/T 15037-1994) was revised. Starting from 1 July 2004, the production and distribution of half-base wine stopped, which means that Chinese wine entered the era of pure-grape juice fermentation [2]. It also freed up nearly one-third of the total market capacity previously occupied by half-base wines for wineries producing high-quality wines, promoting the upgrading of China’s wine industry [5].

From 2004 to 2013, the Chinese wine industry entered a period of rapid ascent. On the one hand, the development of the wine industry benefited from the support of the national strategy, such as in 2002, the State Economic and Trade Committee announced that it would focus on the development of grape wine and other fruit wine. On the other hand, in the early 21st century, Chinese macroeconomic growth, lower import taxes, and free trade agreements supported a more prosperous wine market and more affordable wines for consumers [6]. At the same time, wine enterprises began to attach importance to the construction of raw material bases and brand building, significantly improving the quality of Chinese wine. In line with the wine market’s fast growth, to ensure the healthy development of the wine industry, the relevant departments of the state have improved and enacted a series of standards and regulations referring to the European Union (EU) and other international wine regulations. The EU is not only the largest global wine-producing region and the main importer and exporter of wine but also the most regulated wine market. The EU “quality regulations” are based on the “appellation” system and include several policy instruments such as the geographical delimitation of certain wine areas, rules on winegrowing and production, and rules on labeling [7]. The gradual improvement of the legal supervision system helped the Chinese wine industry enter a new stage of comprehensive standardization from production to market.

However, since 2013, due to the restrictions the Chinese government placed on the utilization of public funds for private banquets and the competitive pressure from imported wine was constantly increasing, the development of the Chinese wine industry (especially in the high-end wine market) has slowed down and entered a fluctuation stage. However, it is encouraging that the general trend of wine consumption in China is certain to rise again in the future, thanks to the rise of the affluent upper-middle class and digital innovations in communication and sales channels [6][8]. This situation reminds researchers that the Chinese wine industry needs to be upgraded urgently in order to overcome the current difficulties and meet a bigger market in the future [9]. Faced with these new challenges, it is worth thinking about how to update the wine policy and legal supervision.

2. Development Process of China’s Wine Industry in the Past 20 Years

2.1. Production of Wine Grapes and Wine

According to the International Organization of Grapes and Wine (OIV) statistics, China has been the world’s largest grape producer since 2011 [10]. However, these grapes were mainly fresh grapes for direct human consumption, while wine grapes accounted for a small part of the production. In 2018, table grape and wine grape accounted for 84.1% and 10.3% of the total grape yield (11.7 million t) in China [11].

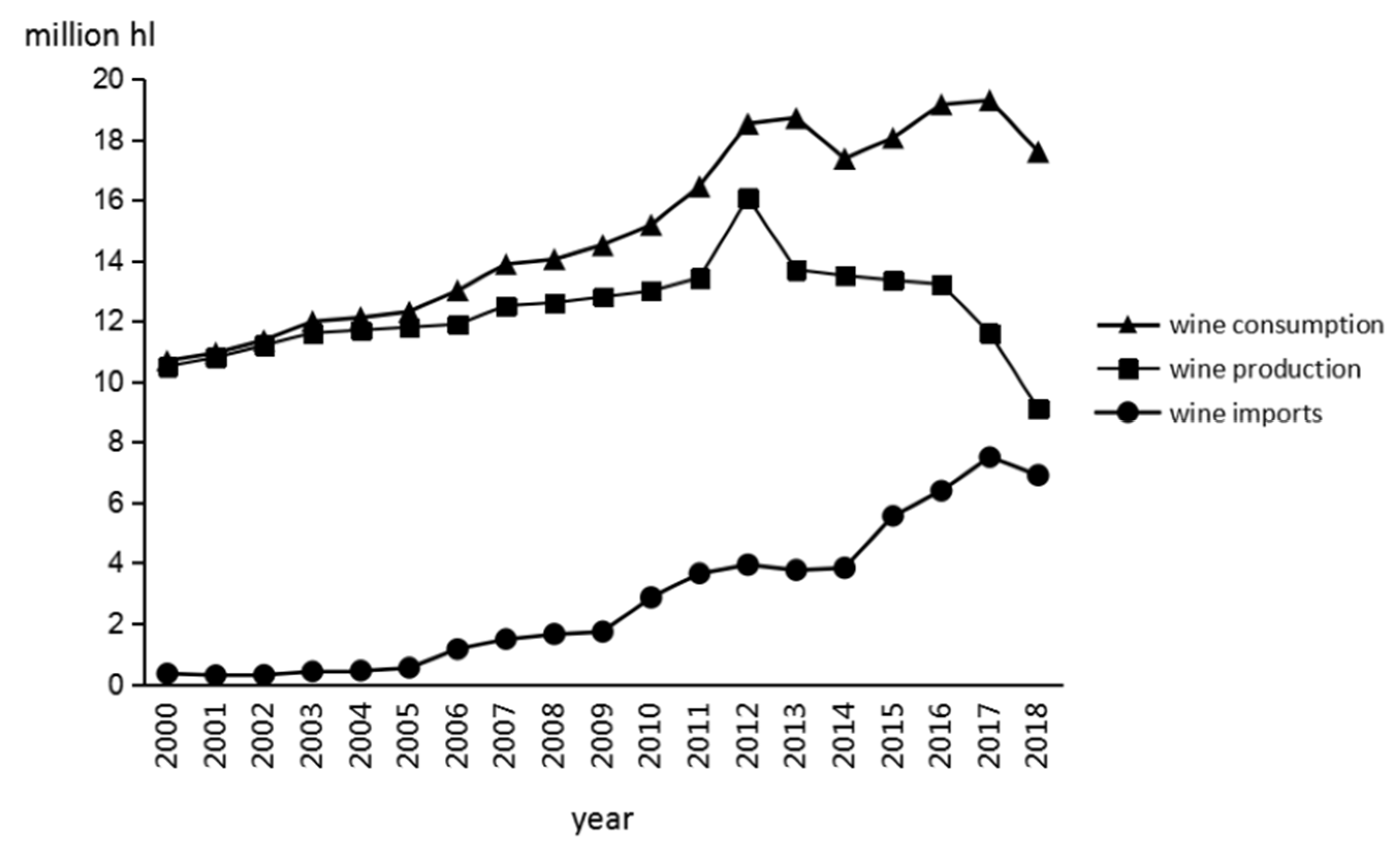

As for wine production, Figure 1 shows that Chinese wine production has been growing continuously since 2000 and reached its peak in 2012 (16.065 million hl). After 2013, the market and policy factors influencing Chinese wine production, the total output of wine expressed a negative trend, and the wine industry entered a period of stagnation [12]. From 2013 to 2018, the average annual decline of wine production was about 7.5%, even though in 2018, Chinese wine production was still as high as 9.1 million hl per year, ranking 10th in the world [11]. The most important reason behind this decline is that the cost of domestic wine is higher than imported wine, which puts China’s domestic production at a disadvantage in price performance and competitiveness. As for the high cost, on the one hand, it depends on the fact that Chinese new wineries need to invest in land, buildings, and equipment. On the other hand, unlike in Europe and the United States, which classify wine as agricultural products, wine in China is a light industrial product, and people have to bear a higher tax burden (13% value-added tax and 10% consumption tax) [13]. Besides, after China acceded to the WTO, China’s tariffs on imported wine have continued to decline, and even some countries have zero taxes (New Zealand, Chile, etc.), which has further widened the cost gap between imported wine and Chinese wine [14].

Figure 1. Wine production, consumption, and imports of China from 2000 to 2018. (Data: source OIV).

2.2. Wine Consumption

The data from OIV indicate that Chinese wine consumption has exceeded wine production since 1997 [15]. From 2000 to 2017, wine consumption generally had a steep growth trend (Figure 1), and China has maintained its position as the fifth-largest global wine consumer since 2007 [10][16]. In 2018, the volume of wine sales was 17.6 million hl, a decrease of 8.8% compared to 2017 (19.3 million hl) [11]. This reduction might be related to the sharp decline in domestic wine production after 2016, even though higher wine imports made up for the market demand gap to a large extent.

2.3. Wine Trade

As visible from Figure 1, with the growth of wine consumption and the decline of wine import tariffs in China, imported wine started to account for an increasing market share. From 2015 to 2018, China maintained the position of the fifth-largest wine importer in the world. In 2018, the import volume of wine was up to 6.7 million hl. Although it was slightly lower than the previous year, it still showed a 79% increase compared to 2014 (3.8 million hl). Likewise, Chinese wine imports’ average annual growth rate from 2013 to 2018 was about 14.2% [11][15]. Compared with imports, the export volume of Chinese wine was still very small. In 2018, the export volume was only 6.37 million L, with Hong Kong accounting for 96.4% of the export market [17].

With the continuous expansion of the Chinese wine market and stronger cooperation between China and other countries in the wine trade, domestic wines will face more intense competitive pressure from imported wines. To promote the competitiveness of Chinese wines and better cope with future opportunities and challenges, the competent Chinese authorities are advancing the amendment and improvement of wine regulations and standards to strengthen the reputation of Chinese wines internationally.

3. Chinese Laws Related to Wine

Nowadays, China has established a basically perfect legal framework for the wine industry, consisting of a series of laws, regulations, and standards issued by the relevant administrative authorities. It covers all the aspects of the wine industry, from land to table, and adjusts the relationship among producers, operators, and consumers, to ensure the safety of wine grape production, wine production processes, and products, and the sound development of the market.

Among the laws regulating the wine industry, the Food Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China is core. Furthermore, some other rules are dealing with other aspects of the wine industry, such as the Product Quality Law, the Agricultural Product Quality Safety Law, the Metrological Law, the Trademark Law, the Environmental Protection Law, the Cleaner Production Promotion Law, the Import and Export Commodity Inspection Law, the Entry and Exit Animal and Plant Quarantine Law, the Frontier Health and Quarantine Law, the Law on Protection of Consumer Rights and Interests, the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, the Criminal Law, and the Standardization Law, etc. [18] The impact of these laws on the Chinese wine market is indirectly reflected through the formulation of standards and regulations. On the one hand, laws are the cornerstone of Chinese standards and regulations, and all of their provisions should not be inconsistent with existing laws. On the other hand, laws endow standards and regulations with certain legal forces, helping them to be effectively implemented on the road to promoting market standardization.

References

- Wang, H.; Ning, X.; Yang, P.; Li, H. Ancient World, Old World and New World of Wine. J. Northwest A F Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 16, 150–153.

- Yang, H.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y. The situation and development trend of wine standards and related regulations in China. China Brew. 2009, 8, 181–183.

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Yang, H. Review of Grape and Wine Industry Development in Recent 30 Years of China’s Reforming and Opening-up. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 25, 341–347.

- Wang, X. The Development of Chinese Wine in Nearly 40 Years. Available online: https://new.qq.com/omn/20200117/20200117A0MI2400.650html (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Lu, Q.F. Research on the Development of Chinese Wine Industry in Modern Times; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2013.

- Zeng, L.; Szolnoki, G. Chapter 2—Some Fundamental Facts about the Wine Market in China. In The Wine Value Chain in China; Roberta, C., Steve, C., David, M., Jingxue, J.Y., Eds.; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 15–36. ISBN 9780081007549.

- Giulia, M.; Johan, S. The Political Economy of European Wine Regulations. J. Wine Econ. 2013, 8, 244–284.

- Ma, N.X. Study on the development strategy of Ningxia wine industry—Taking the eastern foothill of Helan Mountain as an example. Ind. Technol. Forum 2017, 16, 21–25.

- Tang, W.; Liu, S. Review on China Wine Market in 2013. Liquor Making 2014, 41, 14–17.

- OIV. OIV 2017 Report on the World Vitivinicultural Situation. PPT Presentation. 2017. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/oiv-life/oiv-2017-report-on-the-world-vitivinicultural-situation (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- OIV. OIV 2019 Report on the World Vitivinicultural Situation. PPT Presentation. 2019. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/oiv-life/oiv-2019-report-on-the-world-vitivinicultural-situation (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Zhu, X.; Zhu, J.; Mu, W.; Feng, J. Analysis of the industrial distribution of wine in China. Sino-Overseas Grapevine Wine 2019, 3, 71–75.

- Zhong, A.; Zhou, H. Deputy to the National People’s Congress and Chairman of Changyu: Abolish Wine Consumption Tax and Change Unequal Competition between Domestic and Foreign Enterprises. The Economic Observer. 2021. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1693361927656086009&wfr=spider&for=pc. (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Gu, Y. Reducing Taxes and Strengthening Brand Building Will Help Chinese Domestic Wines Catch a Chance to Transcend Imported Wine in Market during the Epidemics of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: http://www.cnfood.cn/hangyexinwen156652.html (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- OIV. The Situation of Vineyard, Grapes and Wine in China. OIV Data, Country Profile. 2016. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/statistiques/?year=2016&countryCode=CHN (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- OIV. Analysis of Wine Consumption in China, UK, Spain, Russia, Argentina and Australia. OIV Data, Database. 2016. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/statistiques/recherche (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- China Industry Information Network. Analysis of the Chinese Wine Industry (Development Process, Industrial Chain, Import and Export, Competitive, etc.) in 2020: The Industry Has Entered a Period of Adjustment. 2020. Available online: https://www.chyxx.com/industry/202001/831009.html (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Yang, H.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Discomfort terms and adjustment suggestions of Chinese wine regulation system. Food Ferment Ind. 2015, 41, 226–234.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.4K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

20 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No