Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antonio Bulum | -- | 2235 | 2022-05-11 22:27:41 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | + 1 word(s) | 2236 | 2022-05-12 02:52:27 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Bulum, A.; Ivanac, G.; , .; Divjak, E. Carotid Artery Disease. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22843 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Bulum A, Ivanac G, , Divjak E. Carotid Artery Disease. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22843. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Bulum, Antonio, Gordana Ivanac, , Eugen Divjak. "Carotid Artery Disease" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22843 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Bulum, A., Ivanac, G., , ., & Divjak, E. (2022, May 11). Carotid Artery Disease. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22843

Bulum, Antonio, et al. "Carotid Artery Disease." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

Carotid artery disease is one of the main global causes of disability and premature mortality in the spectrum of cardiovascular diseases. One of its main consequences, stroke, is the second biggest global contributor to disability and burden via Disability Adjusted Life Years after ischemic heart disease.

carotid artery

carotid plaque

ultrasound

1. Carotid Pathology

Cardiovascular diseases are globally a main cause of disability and premature mortality, with atherosclerosis as the main pathological process. Atherosclerosis begins early during one’s lifetime and predominantly remains asymptomatic until it is already in an advanced stage [1]. This is especially apparent in carotid artery disease, where advanced disease may be latent until the onset of life-threatening conditions, such as stroke, the second largest cause of death globally after ischemic heart disease [2]. In addition to being the second leading cause of mortality, nonfatal episodes of stroke are a major global contributor to disability, and stroke burden via DALY (Disability Adjusted Life Years) is continuously increasing. For 2019, the data show that ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke were the second and third leading cause of DALY, respectively [3].

As mentioned previously, stroke can be divided into ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke, which is further divided into intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ischemic stroke is defined as infarction of the brain, spinal cord or retina and encompasses around 70% of all strokes globally. The majority of them are thromboembolic in origin, with the most common sources of embolism being large artery atherosclerosis and cardiac diseases [4]. Less common causes include arterial dissection, small vessel disease and inflammatory diseases, such as vasculitis. In patients with large artery atherosclerosis, the embolism typically originates from atherosclerotic changes om the internal carotid artery immediately after its origin from the bifurcation of the common carotid artery.

The main risk factors for the development of carotid atherosclerotic changes are the same ones responsible for the development of cardiovascular diseases in general. These include dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, smoking and sedentary lifestyle, as well as advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and its receptors and C-reactive protein (CRP). AGEs are endogenously or exogenously formed glycation products of a protein or lipoprotein. Their blood levels increase with age, with smoking accelerating that process, and they serve as biomarkers of severity of the cardiovascular disease, both carotid and coronary [5]. On the other hand, CRP is an acute phase protein, whose blood levels rise in inflammatory conditions such as infections but also in non-infectious systemic diseases, such as atherosclerosis. The more blood vessels are affected, the higher CRP levels can be detected [6].

The three main pathological processes causing carotid atherosclerotic changes are: increased carotid intima-media thickness, carotid plaque formation and carotid stenosis. In 2020, the most common of these pathologies was increased carotid intima-media thickness, whose global prevalence in the age groups of 30–79 years is 27.6% [1].

Carotid artery wall intima-media-thickness (IMT) is a surrogate measure of carotid atherosclerosis. IMT is measured non-invasively, by ultrasound, as the distance between the lumen–intima and media–adventitia interfaces of the arterial wall. The IMT of the common carotid artery (CCA) and the proximal portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) can both be measured, although, in principle, the measurement of the IMT of the CCA is considered simpler and more appropriate for assessing overall cardiovascular risk [7]. The recent American College of Cardiology Foundation–American Heart Association guidelines gave carotid intima–media thickness a level IIa recommendation for cardiovascular risk evaluation, with an indication of high risk if the common carotid artery IMT is above the 75th percentile [8].

Carotid artery stenosis is defined as a narrowing of its lumen and may clinically be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Symptomatic stenosis is experienced by patients who have suffered a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke due to lumen narrowing or thromboembolic events from the affected artery. It is considered that carotid artery stenosis is responsible for about 10–20% of all strokes, and there has been a long-standing consensus regarding their management [2]. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) and the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST), both published in 1991, outlined the importance of surgery in different groups of symptomatic patients [9].

The diagnosis of asymptomatic carotid stenosis is made when a lumen narrowing is found without the evidence of previous TIA, stroke or focal neurological in the course of 6 months ago [10]. There is still no true consensus regarding the best treatment of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, and the latest European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) guidelines recommend that patients with an average surgical risk and an asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis of 60–99% should be considered for carotid endarterectomy (CEA) only in the presence of one or more characteristics that may be associated with an increased risk of late ipsilateral stroke. Carotid artery stenting (CAS) is also feasible in these patients; however, it is indicated over CEA for patients with a high risk of surgery retaining the increased risk of late ipsilateral stroke [11].

2. UltraFast™ Ultrasound

UltraFast™ (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix en Provence, France) imaging is the new step into the development of medical ultrasonography that allows not only 100 times higher frame rates than conventional ultrasound scanners but also scanning the whole region of interest in one single insonification. In contrast, current ultrasound systems are based on a serialized architecture, and imaging is performed using a series of insonifications of focused beams, and each beam is then used to reconstruct one plane of an image, meaning that the frame rate is limited by the time it takes for echoes to be transmitted, received and processed for all lines of the image.

UltraFast™ approaches this problem with a concept of computing in parallel as many planes as possible so it is able to compute a full image from a single transmit, regardless of the image size and its other characteristics. By using a parallel architecture, the frame rate is no longer limited by the number of planes reconstructed but by the time an ultrasound pulse needs to travel through the insonated tissues and back to the probe [12].

There are several ways in which an ultrafast imaging architecture is conceptualized: the one used for UltraFastTM is based on the use of plane wave insonification [13].

3. Shear Wave Elastography

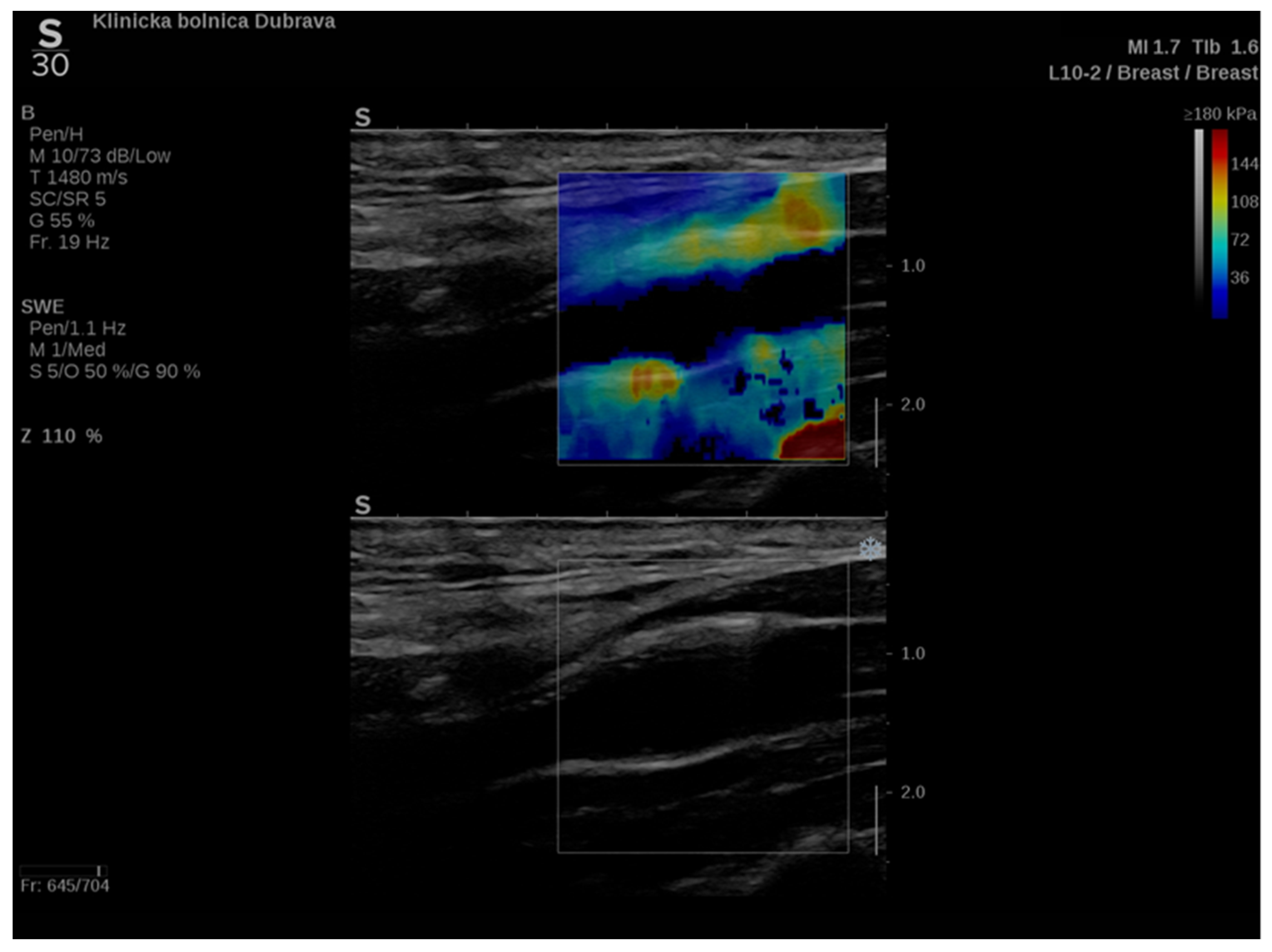

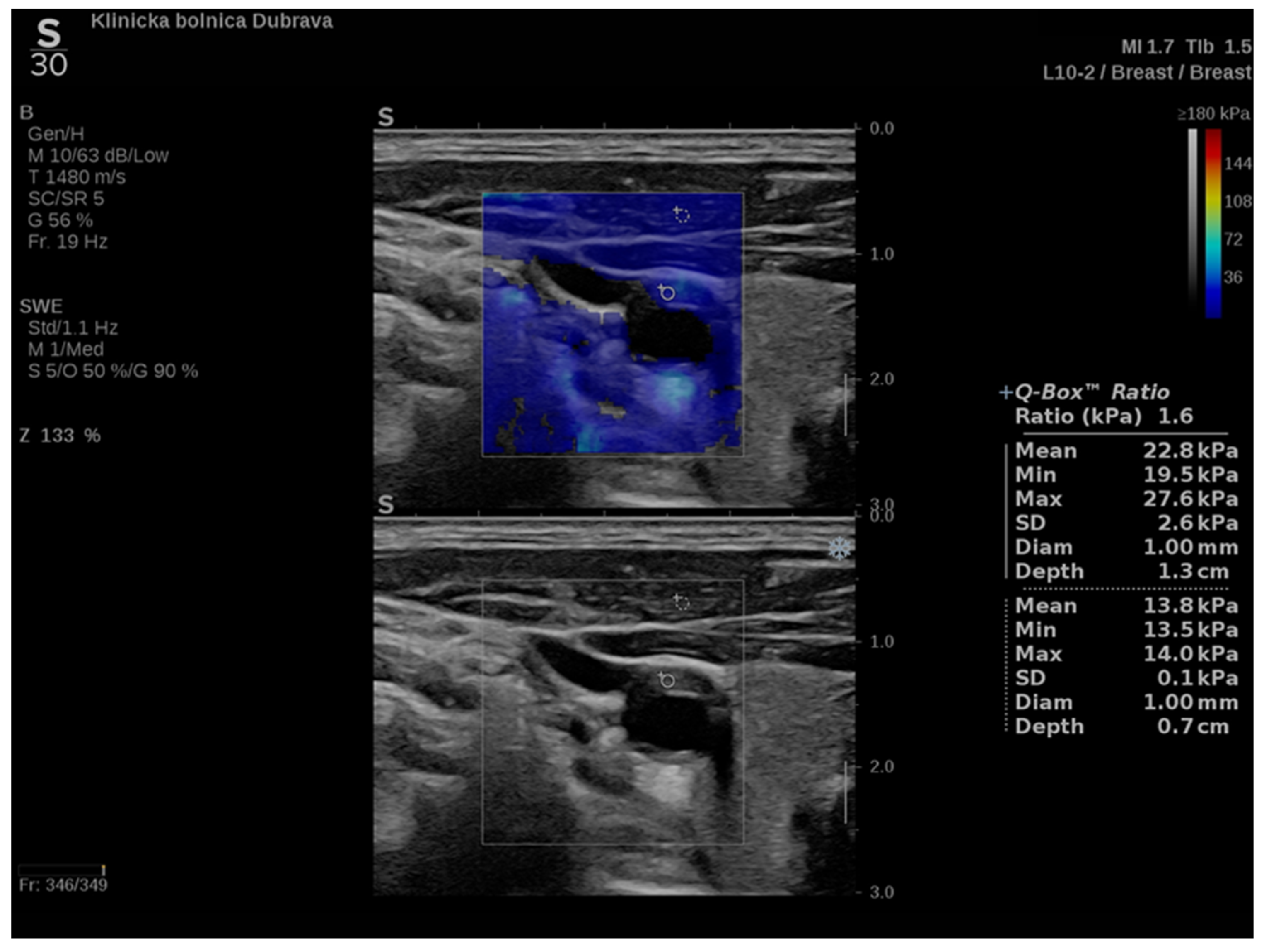

In addition to conventional, Doppler and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, elastography techniques are another area where ultrasound is being increasingly used, this time to assess the elastic properties of the insonated tissue. There are two types of ultrasound elastography: strain and shear wave elastography (SWE). Strain elastography is performed by manual compression using the transducer, which then produces an image based on the resulting displacement of the tissue caused by the compression. However, it is difficult to measure the exact amount of the applied force during compression, resulting in the method being difficult to standardize. Additionally, the absolute elasticity values cannot be calculated, and only qualitative results can be obtained. Unlike strain elastography, SWE is a type of ultrasound elastography where the elastic properties of the insonated tissues can be expressed both qualitatively and quantitatively (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [14].

Figure 1. An example of an ultrasound examination with shear wave elastography of a segment of the distal right CCA in the longitudinal view with B-mode ultrasound at bottom and shear wave elastography at the top where the elastic properties of the examined tissues (carotid artery wall and surrounding soft tissues) are displayed qualitatively by benign color-coded and superimposed on the B-mode image. Red color denotes the stiffest areas with the highest elastic modulus values.

Figure 2. Another example of an ultrasound examination with shear wave elastography of a segment of the CCA, this time in the transverse view. A carotid artery plaque is visible in the wall of the CCA and displayed with B-mode ultrasound at the bottom and shear wave elastography at the top. In this figure, the elastic properties of the examined tissues are displayed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Quantitative measures are visible on the right-hand side of the picture, measured using two regions of interest, one centered over the plaque and another over the adjoining soft tissues, and an elasticity ratio between the two is calculated by the ultrasound device.

In order to understand the principles of SWE elastography, the researchers have to remember that as the ultrasound pulse passes through tissues, it can be reflected, absorbed or it can create tissue displacement. The latter induces mechanical vibrations resulting in shear waves, which are perpendicular to the primary ultrasound wave and propagate through the tissues with measurable speed.

This technique allows the characterization of carotid plaque composition and stability. For example, areas with higher stiffness correspond to calcifications within the plaque, and areas with lower stiffness values to lipid deposits or intraplaque hemorrhage, both indicating characteristics of vulnerable plaques [15]. In addition to that, stiffness values were correlated with the Gray–Weale classification of plaques based on echogenicity and were proven to be statistically significantly lower in symptomatic compared to asymptomatic patients [16]. SWE has also already proven its clinical correlation with stiffness values of the carotid artery wall measured using SWE having a positive correlation with known risk factors of atherosclerosis [17].

In addition to the assessment of carotid arteries, SWE found its use in numerous branches of medicine, from hematology to breast imaging and thyroid mass identification, with promising results in gynecological, urological, neurological and dermatological uses [18][19][20][21].

4. UltraFast™ Doppler

One of the main abilities of ultrasound as a medical imaging modality is tracking blood flow dynamics in real time. Because of that Doppler based techniques of imaging are a mainstay on every modern medical ultrasound device, especially with the framework of cardiovascular imaging, which includes imaging of carotid artery disease. Conventional Doppler ultrasound imaging consists of two modes: Color flow imaging (CFI) and the Pulsed-wave Doppler (PW Doppler).

Tracking blood flow dynamics in CFI is achieved by estimating flow velocity. The flow velocity estimations are based on the use of a number of narrowband pulses which are transmitted at a constant pulse repetition frequency (PRF) in order to estimate the Doppler frequency. The main challenge of this method is how to separate the Doppler flow signals arriving at the probe from all the tissue echoes arriving at the same time and estimate the mean flow velocity. This was done mostly using correlation methods [22].

However, in order to quantify the Doppler signals acquainted via CFI PW Doppler is used. The quantification is achieved by performing an FFT type of spectral analysis which is used to deduce the distribution of Doppler velocities within a sample volume. The results are the displayed as a graph, with velocity as the y-axis and time at the x-axis [23].

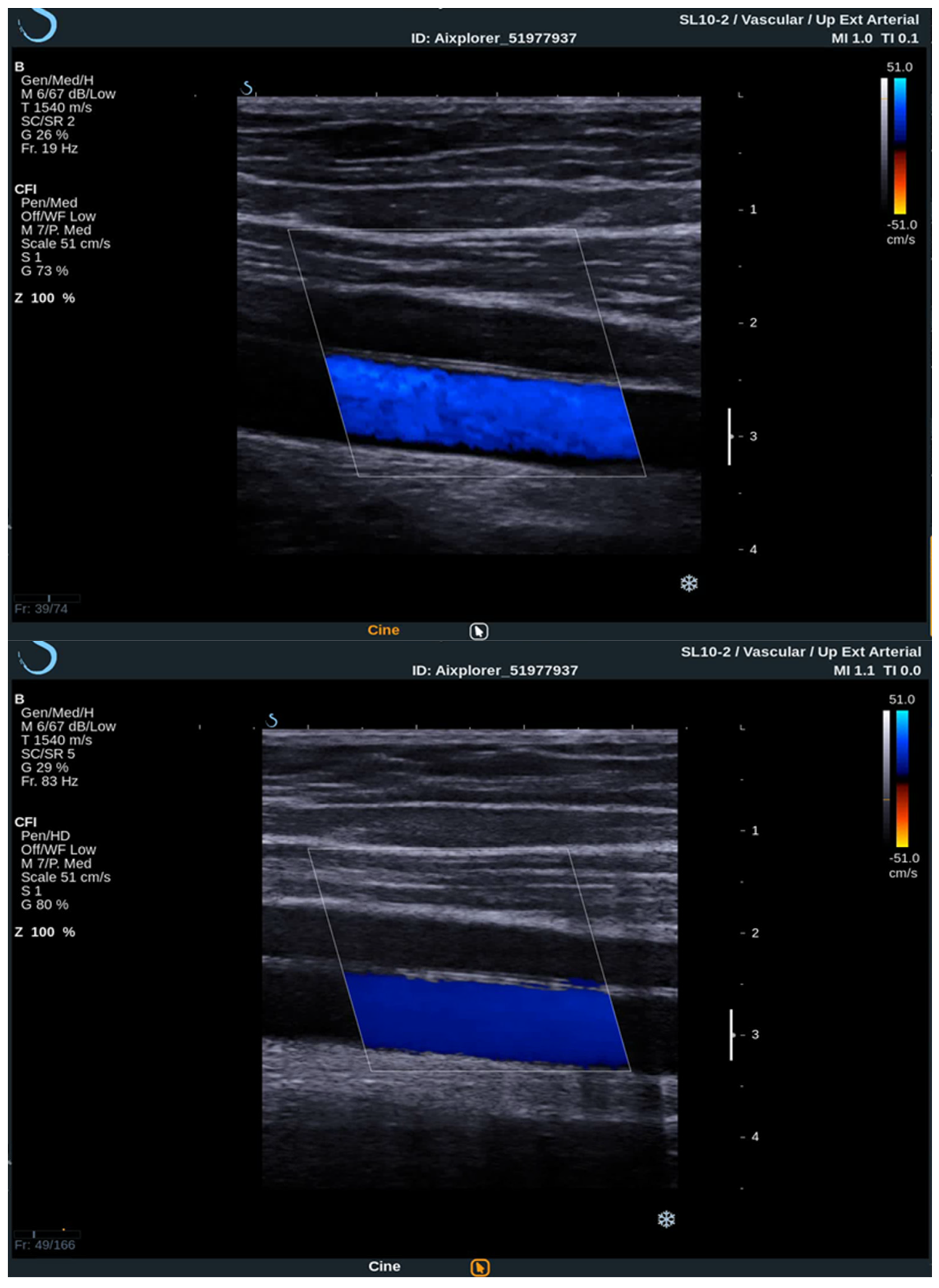

To acquire data from these modes, the practitioner switches between them analyzing the PW Doppler at the locations pinpointed by the color Doppler image. With the introduction of UltraFast™ Doppler (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix en Provence, France), quantitative data can be assessed in all pixels at the same time. Because it relies on plane waves and not focused beams in the image acquisition, there is no time lag at the sides of the image. On a conventional ultrasound device, such quantitative analysis is only possible by limiting the region of interest (ROI) to a single acoustic line. UltraFast™ Doppler allows the merging of CFI and PW Doppler mode in a single acquisition (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison between conventional CFI Doppler ultrasound at the top and UltraFast™ Doppler ultrasound at the bottom while examining a segment of the CCA in the longitudinal view. UltraFast™ Doppler demonstrated excellent flow sensibility and provides a framerate of more than 80 Hz.

High frame rates of UltraFast™ Doppler provide a high temporal resolution on CFI, which enables the visualization of more complex, as well as fast flows. Such flow patterns can be seen in more detail, consequently enabling the examiner to establish more accurate diagnosis. To better visualize the slow flows, high frame rates are traded for higher sensitivity and better spatial resolution. This way some small vessels can only be seen using UltraFast™ Doppler and without the need for intravenous contrast agents.

The high temporal resolution enables a consistent flow of information in the entire imaged area since the received Doppler signals of all the pixels in the image are acquired at the same time. In contrast, conventional color Doppler images are sequentially acquired, the Doppler signals on the edges of the color box arrive to the probe with a delay up to several hundreds of milliseconds in comparison to UltraFast™ Doppler [12].

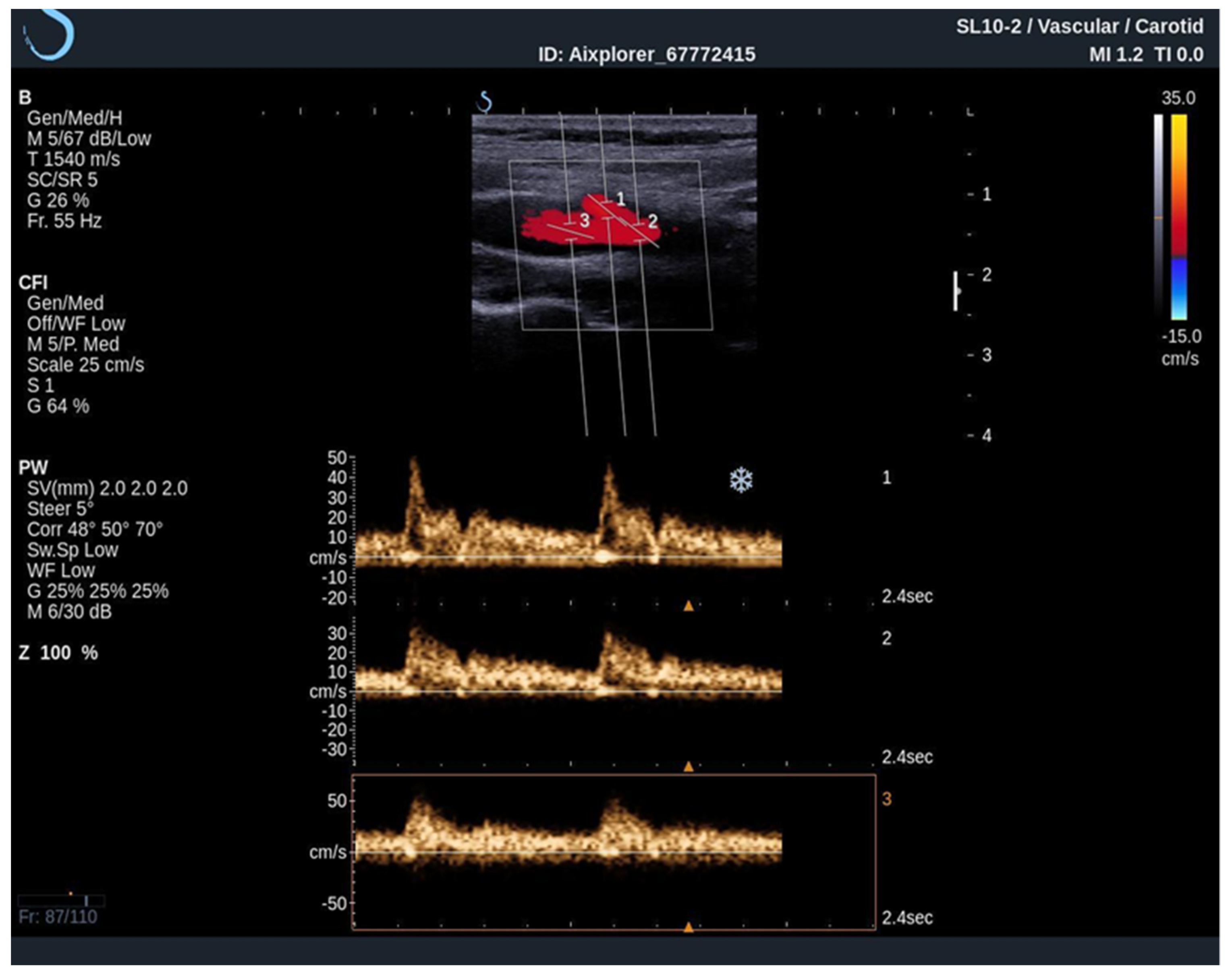

When performing an UltraFast Doppler examination, a single-shot acquisition mode is usually initiated from the conventional color Doppler imaging mode. After that, a range of UltraFast Doppler data is acquired (typically 2 to 4 s), and the picture is frozen. The examiner can then review the UltraFast color flow data, review a single or multiple frames offering the best image visualization of the flow characteristics of interest and simultaneously perform a retrospective spectral analysis of the color box. Furthermore, using UltraFast™ Doppler, a short clip of not only one, but multiple regions of interest can be obtained, providing a more precise comparison of both mean and peak flow velocity originating from the same cardiac cycle (Figure 4) [24].

Figure 4. An UltraFast™ Doppler examination of the bifurcation of the carotid artery. Several measurements can be performed independently of each other with a high degree of reliability since the acquisition is made during the same cardiac cycle. In this example, spectra from the ICA (3) and ECA (2) are analyzed simultaneously, one can differentiate the ICA from the ECA on the basis of spectral morphology with ECA demonstrating a high-resistance spectrum and the ICA demonstrating a low-resistance spectrum.

References

- Song, P.; Fang, Z.; Wang, H.; Cai, Y.; Rahimi, K.; Zhu, Y.; Fowkes, F.G.R.; Fowkes, F.J.I.; Rudan, I. Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, 721–729.

- Mortimer, R.; Nachiappan, S.; Howlett, D.C. Carotid artery stenosis screening: Where are we now? Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170380.

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021.

- Campbell, B.C.V.; De Silva, D.A.; Macleod, M.R.; Coutts, S.B.; Schwamm, L.H.; Davis, S.M.; Donnan, G.A. Ischaemic stroke. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 70.

- Fishman, S.L.; Sonmez, H.; Basman, C.; Singh, V.; Poretsky, L. The role of advanced glycation end-products in the development of coronary artery disease in patients with and without diabetes mellitus: A review. Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 59.

- Liang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Niu, H.; Lu, M.; Xue, L.; Sun, Q. Correlation of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and carotid plaques with coronary artery disease in elderly patients. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 275–278.

- Polak, J.F.; Pencina, M.J.; Pencina, K.M.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Wolf, P.A.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr. Carotid-wall intima-media thickness and cardiovascular events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 213–221.

- Greenland, P.; Alpert, J.S.; Beller, G.A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Budoff, M.J.; Fayad, Z.A.; Foster, E.; Hlatky, M.A.; Hodgson, J.M.; Kushner, F.G.; et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 50–103.

- Cina, C.S.; Clase, C.M.; Haynes, R.B. Carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000, 2, CD001081.

- Halliday, A.; Mansfield, A.; Marro, J.; Peto, C.; Peto, R.; Potter, J.; Thomas, D.; MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative Group. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: Randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 363, 1491–1502.

- Naylor, A.R.; Ricco, J.B.; de Borst, G.J.; Debus, S.; de Haro, J.; Halliday, A.; Hamilton, G.; Kakisis, J.; Kakkos, S.; Lepidi, S.; et al. Editor’s choice—Management of atherosclerotic carotid and vertebral artery disease: 2017 clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 55, 3–81.

- Bercoff, J. Ultrafast Ultrasound Imaging; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011.

- Montaldo, G.; Tanter, M.; Bercoff, J.; Benech, N.; Fink, M. Coherent plane-wave compounding for very high frame rate ultrasonography and transient elastography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2009, 56, 489–506.

- Ozturk, A.; Grajo, J.R.; Dhyani, M.; Anthony, B.W.; Samir, A.E. Principles of ultrasound elastography. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 773–785.

- Goudot, G.; Khider, L.; Pedreira, O.; Poree, J.; Julia, P.; Alsac, J.M.; Amemiya, K.; Bruneval, P.; Messas, E.; Pernot, M.; et al. Innovative Multiparametric Characterization of Carotid Plaque Vulnerability by Ultrasound. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 157.

- Ramnarine, K.V.; Garrard, J.W.; Kanber, B.; Nduwayo, S.; Hartshorne, T.C.; Robinson, T.G. Shear wave elastography imaging of carotid plaques: Feasible, reproducible and of clinical potential. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2014, 12, 49.

- Marais, L.; Pernot, M.; Khettab, H.; Tanter, M.; Messas, E.; Zidi, M.; Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P. Arterial Stiffness Assessment by Shear Wave Elastography and Ultrafast Pulse Wave Imaging: Comparison with Reference Techniques in Normotensives and Hypertensives. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2019, 45, 758–772.

- Zhang, M.; Wasnik, A.P.; Masch, W.R.; Rubin, J.M.; Carlos, R.C.; Quint, E.H.; Maturen, K.E. Transvaginal Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography for the Evaluation of Benign Uterine Pathologies: A Prospective Pilot Study. J. Ultrasound Med. 2019, 38, 149–155.

- Cui, A.; Xu, L.; Mu, J.; Tong, M.; Peng, C.; Wu, T. The role of shear wave elastography on evaluation of the rigidity changes of corpus cavernosum penis in venogenic erectile dysfunction. Eur. J. Radiol. 2018, 103, 1–5.

- Liu, Y.L.; Liu, D.; Xu, L.; Su, C.; Li, G.Y.; Qian, L.X.; Cao, Y. In vivo and ex vivo elastic properties of brain tissues measured with ultrasound elastography. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 83, 120–125.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yan, F.; Xiang, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Qiu, L. Determination of Normal Skin Elasticity by Using Real-time Shear Wave Elastography. J. Ultrasound Med. 2018, 37, 2507–2516.

- Loupas, T.; Powers, J.T.; Gill, R.W. An axial velocity estimator for ultrasound blood flow imaging, based on a full evaluation of the Doppler equation by means of a two-dimensional autocorrelation approach. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 1995, 42, 672–688.

- Bercoff, J.; Montaldo, G.; Loupas, T.; Savery, D.; Mézière, F.; Fink, M.; Tanter, M. Ultrafast compound Doppler imaging: Providing full blood flow characterization. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2011, 58, 134–147.

- Tanter, M.; Fink, M. Ultrafast imaging in biomedical ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2014, 61, 102–119.

More

Information

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

698

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

12 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No