Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thomas Dittmar | -- | 2333 | 2022-05-05 14:53:16 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2333 | 2022-05-06 04:35:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Dittmar, T. Cancer Stem/Initiating Cells. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22622 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

Dittmar T. Cancer Stem/Initiating Cells. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22622. Accessed January 15, 2026.

Dittmar, Thomas. "Cancer Stem/Initiating Cells" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22622 (accessed January 15, 2026).

Dittmar, T. (2022, May 05). Cancer Stem/Initiating Cells. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22622

Dittmar, Thomas. "Cancer Stem/Initiating Cells." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

CS/ICs have raised great expectations in cancer research and therapy, as eradication of this key cancer cell type is expected to lead to a complete cure. Unfortunately, the biology of CS/ICs is rather complex, since no common CS/IC marker has yet been identified. Certain surface markers or ALDH1 expression can be used for detection, but some studies indicated that cancer cells exhibit a certain plasticity, so CS/ICs can also arise from non-CS/ICs. Another problem is intratumoral heterogeneity, from which it can be inferred that different CS/IC subclones must be present in the tumor.

cell-cell fusion

cancer

cancer stem/initiating cells

1. Introduction

The concept of cell–cell fusion in cancer was already proposed more than a century ago by the German physician Otto Aichel [1]. He assumed (a) that the fusion of tumor cells and cancer infiltrating leukocytes could be an explanation for aneuploidy and (b) that the combination of different chromosomes and their qualitative differences could lead to a metastatic phenotype (for review, see [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]). Since then, the fusogenic capacity of cancer cells has been demonstrated in a variety of in vitro and in vivo studies. It was shown that cancer cells could either fuse with other cancer cells or normal cells, such as macrophages, fibroblasts, stromal cells, and stem cells, thereby generating tumor hybrid cells exhibiting an increased metastatogenic capacity, an enhanced resistance to chemo- and radiation therapy, and even properties of cancer stem/initiating cells (CS/ICs) (for review, see [3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]). Moreover, tumor hybrids have been clearly identified in human cancer patients with a former bone marrow transplantation (BMT) history [12][13][14][15][16][17]. For instance, tumor hybrid cells with overlapping donor and recipient alleles were found in the primary tumor, lymph node metastases, and brain metastases of melanoma patients [13][14][15]. Likewise, Y-chromosome positive tumor hybrid cells were found in the primary cancer and the circulation of female pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients, which received a BMT from a male donor [17]. Moreover, the presence of circulating tumor hybrid cells as compared to normal circulating tumor cells was correlated to a statistically significantly increased risk of death in pancreatic cancer patients [17], suggesting that the cancer cells’ malignancy was dramatically enhanced by fusion. Briefly, these human cancer data support the theory that (a) cell–cell fusion events really occur in human cancers and that (b) cell–cell fusion could give rise to tumor hybrid cells exhibiting an altered phenotype.

CS/ICs represent a small population of cancer cells exhibiting stem-cell properties (for review, see [18][19][20][21][22][23][24]) and prospective CS/ICs have been identified in leukemia [25][26] and various solid tumors, including breast, prostate, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, and glioblastoma [27][28][29][30][31][32]. In addition to their tumor initiating potential, CS/ICs may also induce metastases [33][34] and could be responsible for tumor relapse after therapy [35][36][37]. Hence, CS/ICs are of pivotal interest in cancer research and therapy, as their destruction would deprive the tumor of its source [35][38].

What sounds simple and promising on the one hand, is actually very complex. First, prospective CS/ICs are usually characterized by the expression of specific markers (for review, see [18][19][20][21][22][23][24]), but no common CS/IC marker has been identified so far. Moreover, a few studies suggest some plasticity of cancer cells, such that non-CS/ICs can become CS/ICs [39][40][41][42]. Second, the capacity of CS/ICs to induce tumor formation is studied in immunocompromised mice [43]. This is advantageous since defined mouse strains guarantee comparable and reliable results. In contrast, the murine tumor environment is barely comparable with the human tumor microenvironment. Thus, human CS/ICs will respond differently to murine cytokines, matrix components, or murine cells, which all have an impact on the cells’ tumorigenicity. Moreover, the tumorigenicity of CS/ICs is also influenced by co-implantation of, e.g., matrix components and stromal cells [19][44]. Third, the originally proposed CS/IC model cannot explain intra-tumoral heterogeneity, which is a hallmark of cancer [45]. Instead of a clone of more or less identical CS/ICs, which were derived from the initial CS/IC by symmetric division, it is currently assumed that the CS/IC pool within a tumor is more heterogeneous, suggesting that different CS/IC subclones co-exist and drive tumor progression [19][23].

2. Some Brief Facts about CS/ICs

Even though prospective CS/ICs have been characterized by expression of specific markers, such as CD24, CD44, CD90, CD133, and ALDH1 (for review, see [18][19][20][21][22][23][24]), no common CS/IC marker has been identified so far and, for some CS/ICs, different markers have been proposed (Table 1). For instance, CD133 has been suggested as a marker for glioblastoma, pancreatic, and prostate CS/ICs [46][47][48], while putative breast CS/ICs have been designated as CD44+/CD24−/low [27]. Interestingly, mouse mammary Brca1 tumors contained distinct CD44+/CD24− and CD133+ cells with CS/IC characteristics [49], whereas three distinct triple negative breast CS/IC populations (both CD44+/CD24− and CD44+/CD24+ in estrogen receptor α-negative breast tumors, and CD44+/CD49fhi/CD133/2hi) were tumorigenic in murine xenograft models [50]. Hermann and colleagues identified two distinct prospective CS/IC populations in pancreatic cancer. CD133+ CS/ICs were found in the center of the primary tumor, whereas CD133+ CXCR4+ CS/ICs were present in the invasive front of pancreatic cancer and determined the metastatic phenotype [48]. However, a contrastingly different CD44+CD24+ESA+ pancreatic CS/IC phenotype has been suggested by Li and colleagues [29]. Epithelial cell-adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and CD44 have been suggested as more robust colon CS/IC markers [31] than CD133 [51][52]. However, CD133+CD44+CD49high colon cancer cells were highly tumorigenic in a study of Haraguchi and colleagues [53].

Table 1. Prospective CS/IC marker.

| Cancer Type | CS/IC Marker | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | CD44+/CD24−/low | [27][49][50] |

| CD44+/CD24+ | [50] | |

| CD44+/CD49fhi/CD133/2hi | [50] | |

| CD133+ | [49] | |

| ALDH1 | [28] | |

| SP cells | [54] | |

| EMT | [55] | |

| Colon Cancer | CD44+EpCam+ | [31] |

| CD133+ | [51][52] | |

| CD133+CD44+CD49high | [53] | |

| Glioblastoma | CD133+ | [46] |

| CD133+/CD133− | [40][41] | |

| SP cells | [56] | |

| Lung Cancer | SP cells | [57] |

| Malignant Melanoma | CD271+ | [58] |

| CD271+/CD271− | [39] | |

| SP cells | [59] | |

| Osteosarcoma | SP cells | [60] |

| Pancreatic Cancer | CD44+CD24+ESA+ | [29] |

| CD133 | [48] | |

| SP cells | [61] |

In addition to the inconsistency of prospective CS/ICs markers, various studies revealed that non-CS/ICs could be as tumorigenic as CS/ICs and that CS/IC-related markers were reversibly expressed in non-CS/ICs and CS/ICs [39][40][41][42]. For instance, CD271 has been suggested as a marker for melanoma CS/ICs [58], but both CD271+ and CD271− melanoma cells were highly tumorigenic and metastatic in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) interleukin-2 receptor-gamma mice (NSG mice) [39]. CD133+ and CD133− glioblastoma CS/ICs showed differential growth characteristics and molecular profiles, but both subtypes were similarly tumorigenic in nude mice [41]. Interestingly, Wang et al. showed that CD133− glioma cells were tumorigenic in nude rats and could give rise to CD133+ cells [40], which have been suggested as glioblastoma CS/ICs [46]. While these findings point to a possible plasticity of cancer cells, these data again raise the reliability of certain markers in CS/IC research.

Side population cells (SP cells) represent another population of tumor initiating cancer cells [57][62][63][64][65]. They are characterized by expression of ATP binding cassette (ABC) membrane transporters and the efflux of fluorescent dyes, such as Hoechst blue and Hoechst red, which are usually used for detection and isolation [57][62][63][64][65]. SP cells have been identified in several tumor cell lines derived from, e.g., breast cancer [54], lung cancer [57], glioblastoma [56], and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [61], and human cancers, such as breast [54], melanoma [59], and osteosarcoma [60] (Table 1). While all these studies showed that SP cells were highly tumorigenic, it remains less clear whether SP cells are identical to the above-mentioned population of CS/ICs or represent a unique population of tumorigenic cancer cells. Studies on pancreatic cancer SP cells revealed that, at less than 1000 cells, tumor formation was initiated in nude mice, but that both non-SP cells and SP cells contained CD44+CD24+ and CD133+ cells [61]. As indicated above, CD44, CD24, and CD133 have been proposed as markers for prospective pancreatic CS/ICs [29][48]. Likewise, no correlation between breast cancer SP cells and the prospective breast CS/IC phenotype CD44+CD24−/low was observed [54]. About 3.4% SP cells were present in the population of MCF-7/HER2 breast cancer cells and only 100 of these MCF-7/HER2 SP cells sufficiently initiated tumor formation in NOD/SCID mice. However, solely 7.4% of MCF-7/HER2 breast cancer cells were CD44+/CD24−/low [54].

In 2008, two different studies suggested a link between epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and generation of normal stem cells and CS/ICs [55][66] (Table 1). The transition of sessile epithelial cells into motile mesenchymal cells is usually associated with cancer metastasis [67][68][69][70], but, of course, is also mandatory for developmental processes during embryogenesis and wound healing [71]. EMT is a reversible process and, hence, cells that have undergone EMT could revert to an epithelial state via mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [70]. Several EMT-inducing triggers have been identified, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), WNT proteins, cytokines, growth factors, and hypoxia, which leads to the expression and functional activation of various master EMT regulators, specifically EMT-inducing transcription factors (EMT-TFs) and microRNAs [68][72]. In this context, two core EMT circuits/feedback loops have been identified, consisting of SNAIL-miR-34 and ZEB1-miR-200 [73], which are accompanied by additional EMT-TFs, including SLUG, TWIST, and YAP/TAZ, as well as post-translational modifications and splicing [71][72]. Interestingly, mathematical modeling of the two core EMT circuits revealed that cells could attain either an E, or an M or an E/M phenotype depending on their SNAIL expression levels [73]. It is this E/M phenotype, which has also been named hybrid E/M state [73][74][75] or quasi-mesenchymal [68], that likely possesses CS/ICs properties. For instance, single CD24+/CD44+ HMLER cells (human mammary epithelial cells immortalized and transformed with hTERT, SV40LT, and RAS oncogenes [76]) exhibited a hybrid E/M phenotype and possessed increased stem-like properties, such as an enhanced population of ALDH1+ cells and mammosphere formation capacity [74]. Likewise, tumorigenic cancer cells expressing both E- and M-specific markers have been found in xenografts isolated from breast [77] and ovarian tumors [78]. Data of Kroger and colleagues further indicated that the hybrid E/M phenotype in HMLER cells is likely controlled by SNAIL, whereas the M phenotype is driven by ZEB1 [79]. HMLER cells that were trapped in a hybrid E/M state (ZEB1 knock-out, SNAIL expression) produced much bigger tumors and displayed a 37-fold higher tumor-initiating frequency as compared to appropriate controls [79]. In this context, integrin-β4 (CD104) has been suggested as a marker for the hybrid E/M state in triple negative breast cancer. Indeed, human breast cancer cells with an intermediate level of integrin-β4 expression exhibited a hybrid E/M state and were more tumorigenic than breast cancer cells in the E-state or M-state, respectively [80].

Tumor initiation and self-renewal of prospective CS/ICs is usually studied in the so-called serial transplantation assay, which, however, is still imperfect, since human cancer cells are growing in a nonhuman environment, namely immunocompromised mice [43]. Hence, it remains unclear whether tumor formation was truly related to CS/ICs or to cancer cells, which adopted best to the foreign murine environment. Moreover, the tumor initiation capacity of prospective CS/ICs is strongly related to the used mouse model (detection of tumorigenic cells is several orders of magnitude higher in NSG mice than in NOD/SCID mice [81]) and co-implantation of matrix components and additional tumor propagating cells [82]. It is well known that the right composition of the tumor microenvironment and the CS/IC niche, including matrix components, stromal cells, immunocompetent cells, hypoxia, and cytokines, potentially contribute to stemness and an enhanced tumor initiation capacity [19][44]. In any case, CS/ICs were clearly identified in genetically engineered mouse models of brain, skin, and intestinal cancers [37][83][84], which are, to date, the strongest evidence that CS/ICs exist and initiate tumor growth.

In summary, the biology of CS/ICs is complex. Although various strategies and protocols have been developed over the past two decades to identify and characterize potential CS/ICs in human cancers, it is still not clear which method and which characterization is the best and most reliable. Moreover, the “classical CS/IC” model fails in intratumoral heterogeneity, which is a hallmark of cancer [45]. Based on the classical CS/IC model, there should be a population of CS/IC in the tumor that arose by self-renewal and should, therefore, be phenotypically similar. However, this is not the case. Instead, different subclones are likely found in the tumor, each of them most likely originating from one subclone-specific CS/IC [19][23].

However, how does this pool of subclone-specific CS/IC evolve? One possible mechanism could be the accumulation of genetic mutations in one CS/IC that could lead to the evolution of subclone-specific CS/ICs [23]. Likewise, it cannot be ruled out that subclone specific CS/ICs evolve independently of the original tumor-initiating CS/IC. As mentioned above, some cancer cells appear to exhibit some plasticity, so that non-CS/ICs can give rise to CS/ICs [39][40][41][42], which could be the result of a microenvironmental cue or a (epi-)genetic change [19]. The hybrid E/M state model assumes that cancer cells could acquire a CS/IC phenotype through EMT [68][73][74][75]. Since EMT is induced in several cancer cells it can be further assumed that a number of hybrid E/M state cancer cells will be generated exhibiting prospective CS/IC properties. Thus, the hybrid E/M state model suits better to intratumoral heterogeneity and the necessity of individual CS/IC subclones.

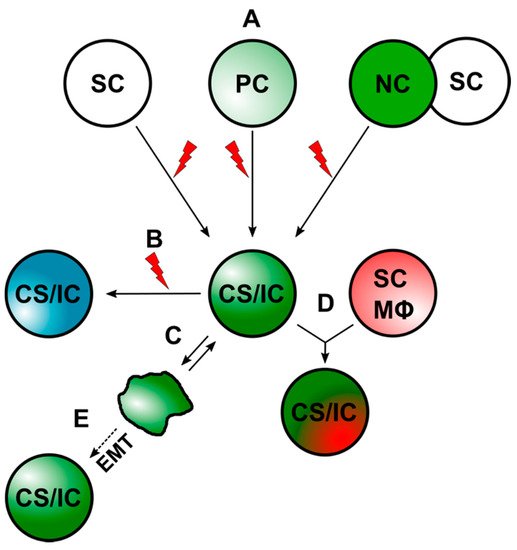

Cell–cell fusion has been suggested as another possible mechanism by which prospective CS/ICs may arise [10][36][85][86][87][88][89][90]. Thereby, CS/ICs might originate from the fusion between stem cells and somatic cells [90] or tumor cells and normal cells, such as macrophages and stem cells [10][36][85][86][87][88][89][90]. A summary of the different ways that CS/ICs could arise is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. CS/ICs can arise through different mechanisms. (A) CS/ICs could originate from normal stem cells (SCs), progenitor cells (PCs), or through cell–cell fusion. The red lightning should indicate mutational events, which drive malignant transformation. (B) Mutational events could lead to a new CS/IC subclone. (C) Differentiated cancer cells could convert into CS/ICs due to an inherent plasticity. (D). CS/ICs could fuse with normal somatic cells (NC), such as stem cells (SC) and macrophages (Mϕ). (E) Induction of EMT in cancer cells might also give to a CS/IC phenotype.

References

- Aichel, O. Über Zellverschmelzung mit quantitativ abnormer Chromosomenverteilung als Ursache der Geschwulstbildung. In Vorträge und Aufsätze über Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen; Roux, W., Ed.; Wilhelm Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1911; pp. 1–115.

- Pawelek, J.M.; Chakraborty, A.K. Fusion of tumour cells with bone marrow-derived cells: A unifying explanation for metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 377–386.

- Duelli, D.; Lazebnik, Y. Cell fusion: A hidden enemy? Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 445–448.

- Lu, X.; Kang, Y. Cell fusion as a hidden force in tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 8536–8539.

- Hass, R.; von der Ohe, J.; Dittmar, T. Hybrid Formation and Fusion of Cancer Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Cancers 2021, 13, 4496.

- Hass, R.; von der Ohe, J.; Dittmar, T. Cancer Cell Fusion and Post-Hybrid Selection Process (PHSP). Cancers 2021, 13, 4636.

- Dittmar, T.; Weiler, J.; Luo, T.; Hass, R. Cell-Cell Fusion Mediated by Viruses and HERV-Derived Fusogens in Cancer Initiation and Progression. Cancers 2021, 13, 5363.

- Zhang, H.; Ma, H.; Yang, X.; Fan, L.; Tian, S.; Niu, R.; Yan, M.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, S. Cell Fusion-Related Proteins and Signaling Pathways, and Their Roles in the Development and Progression of Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 809668.

- Pawelek, J.; Chakraborty, A.; Lazova, R.; Yilmaz, Y.; Cooper, D.; Brash, D.; Handerson, T. Co-opting macrophage traits in cancer progression: A consequence of tumor cell fusion? Contrib. Microbiol. 2006, 13, 138–155.

- Hass, R.; von der Ohe, J.; Ungefroren, H. Potential Role of MSC/Cancer Cell Fusion and EMT for Breast Cancer Stem Cell Formation. Cancers 2019, 11, 1432.

- Was, H.; Borkowska, A.; Olszewska, A.; Klemba, A.; Marciniak, M.; Synowiec, A.; Kieda, C. Polyploidy formation in cancer cells: How a Trojan horse is born. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 81, 24–36.

- Chakraborty, A.; Lazova, R.; Davies, S.; Backvall, H.; Ponten, F.; Brash, D.; Pawelek, J. Donor DNA in a renal cell carcinoma metastasis from a bone marrow transplant recipient. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004, 34, 183–186.

- LaBerge, G.S.; Duvall, E.; Grasmick, Z.; Haedicke, K.; Pawelek, J. A Melanoma Lymph Node Metastasis with a Donor-Patient Hybrid Genome following Bone Marrow Transplantation: A Second Case of Leucocyte-Tumor Cell Hybridization in Cancer Metastasis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168581.

- LaBerge, G.; Duvall, E.; Grasmick, Z.; Haedicke, K.; Galan, A.; Pawelek, J. A melanoma patient with macrophage-cancer cell hybrids in the primary tumor, a lymph node metastasis and a brain metastasis. Cancer Genet. 2021, 256–257, 162–164.

- Lazova, R.; Laberge, G.S.; Duvall, E.; Spoelstra, N.; Klump, V.; Sznol, M.; Cooper, D.; Spritz, R.A.; Chang, J.T.; Pawelek, J.M. A Melanoma Brain Metastasis with a Donor-Patient Hybrid Genome following Bone Marrow Transplantation: First Evidence for Fusion in Human Cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66731.

- Yilmaz, Y.; Lazova, R.; Qumsiyeh, M.; Cooper, D.; Pawelek, J. Donor Y chromosome in renal carcinoma cells of a female BMT recipient: Visualization of putative BMT-tumor hybrids by FISH. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005, 35, 1021–1024.

- Gast, C.E.; Silk, A.D.; Zarour, L.; Riegler, L.; Burkhart, J.G.; Gustafson, K.T.; Parappilly, M.S.; Roh-Johnson, M.; Goodman, J.R.; Olson, B.; et al. Cell fusion potentiates tumor heterogeneity and reveals circulating hybrid cells that correlate with stage and survival. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat7828.

- Bocci, F.; Gearhart-Serna, L.; Boareto, M.; Ribeiro, M.; Ben-Jacob, E.; Devi, G.R.; Levine, H.; Onuchic, J.N.; Jolly, M.K. Toward understanding cancer stem cell heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 148–157.

- Prasetyanti, P.R.; Medema, J.P. Intra-tumor heterogeneity from a cancer stem cell perspective. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 41.

- Walcher, L.; Kistenmacher, A.K.; Suo, H.; Kitte, R.; Dluczek, S.; Strauß, A.; Blaudszun, A.R.; Yevsa, T.; Fricke, S.; Kossatz-Boehlert, U. Cancer Stem Cells-Origins and Biomarkers: Perspectives for Targeted Personalized Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1280.

- Huang, T.; Song, X.; Xu, D.; Tiek, D.; Goenka, A.; Wu, B.; Sastry, N.; Hu, B.; Cheng, S.Y. Stem cell programs in cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8721–8743.

- Reddy, K.B. Stem Cells: Current Status and Therapeutic Implications. Genes 2020, 11, 1372.

- Kreso, A.; Dick, J.E. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 275–291.

- Medema, J.P. Cancer stem cells: The challenges ahead. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 338–344.

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 730–737.

- Lapidot, T.; Sirard, C.; Vormoor, J.; Murdoch, B.; Hoang, T.; Caceres-Cortes, J.; Minden, M.; Paterson, B.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Dick, J.E. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994, 367, 645–648.

- Al-Hajj, M.; Wicha, M.S.; Benito-Hernandez, A.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3983–3988.

- Ginestier, C.; Hur, M.H.; Charafe-Jauffret, E.; Monville, F.; Dutcher, J.; Brown, M.; Jacquemier, J.; Viens, P.; Kleer, C.G.; Liu, S.; et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 555–567.

- Li, C.; Heidt, D.G.; Dalerba, P.; Burant, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Adsay, V.; Wicha, M.; Clarke, M.F.; Simeone, D.M. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 1030–1037.

- Collins, A.T.; Berry, P.A.; Hyde, C.; Stower, M.J.; Maitland, N.J. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 10946–10951.

- Dalerba, P.; Dylla, S.J.; Park, I.K.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Cho, R.W.; Hoey, T.; Gurney, A.; Huang, E.H.; Simeone, D.M.; et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10158–10163.

- Singh, S.K.; Clarke, I.D.; Terasaki, M.; Bonn, V.E.; Hawkins, C.; Squire, J.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 5821–5828.

- Li, F.; Tiede, B.; Massague, J.; Kang, Y. Beyond tumorigenesis: Cancer stem cells in metastasis. Cell Res. 2007, 17, 3–14.

- Dieter, S.M.; Ball, C.R.; Hoffmann, C.M.; Nowrouzi, A.; Herbst, F.; Zavidij, O.; Abel, U.; Arens, A.; Weichert, W.; Brand, K.; et al. Distinct types of tumor-initiating cells form human colon cancer tumors and metastases. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 9, 357–365.

- Colak, S.; Medema, J.P. Cancer stem cells--important players in tumor therapy resistance. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 4779–4791.

- Dittmar, T.; Nagler, C.; Schwitalla, S.; Reith, G.; Niggemann, B.; Zanker, K.S. Recurrence cancer stem cells--made by cell fusion? Med. Hypotheses 2009, 73, 542–547.

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, T.S.; McKay, R.M.; Burns, D.K.; Kernie, S.G.; Parada, L.F. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature 2012, 488, 522–526.

- Hombach-Klonisch, S.; Paranjothy, T.; Wiechec, E.; Pocar, P.; Mustafa, T.; Seifert, A.; Zahl, C.; Gerlach, K.L.; Biermann, K.; Steger, K.; et al. Cancer stem cells as targets for cancer therapy: Selected cancers as examples. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2008, 56, 165–180.

- Quintana, E.; Shackleton, M.; Foster, H.R.; Fullen, D.R.; Sabel, M.S.; Johnson, T.M.; Morrison, S.J. Phenotypic heterogeneity among tumorigenic melanoma cells from patients that is reversible and not hierarchically organized. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 510–523.

- Wang, J.; Sakariassen, P.O.; Tsinkalovsky, O.; Immervoll, H.; Boe, S.O.; Svendsen, A.; Prestegarden, L.; Rosland, G.; Thorsen, F.; Stuhr, L.; et al. CD133 negative glioma cells form tumors in nude rats and give rise to CD133 positive cells. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 761–768.

- Beier, D.; Hau, P.; Proescholdt, M.; Lohmeier, A.; Wischhusen, J.; Oefner, P.J.; Aigner, L.; Brawanski, A.; Bogdahn, U.; Beier, C.P. CD133(+) and CD133(−) glioblastoma-derived cancer stem cells show differential growth characteristics and molecular profiles. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4010–4015.

- Shmelkov, S.V.; Butler, J.M.; Hooper, A.T.; Hormigo, A.; Kushner, J.; Milde, T.; St Clair, R.; Baljevic, M.; White, I.; Jin, D.K.; et al. CD133 expression is not restricted to stem cells, and both CD133+ and CD133− metastatic colon cancer cells initiate tumors. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2111–2120.

- Clarke, M.F.; Dick, J.E.; Dirks, P.B.; Eaves, C.J.; Jamieson, C.H.; Jones, D.L.; Visvader, J.; Weissman, I.L.; Wahl, G.M. Cancer stem cells--perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 9339–9344.

- Malanchi, I.; Santamaria-Martinez, A.; Susanto, E.; Peng, H.; Lehr, H.A.; Delaloye, J.F.; Huelsken, J. Interactions between cancer stem cells and their niche govern metastatic colonization. Nature 2012, 481, 85–89.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Liu, G.; Yuan, X.; Zeng, Z.; Tunici, P.; Ng, H.; Abdulkadir, I.R.; Lu, L.; Irvin, D.; Black, K.L.; Yu, J.S. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol. Cancer 2006, 5, 67.

- Miki, J.; Furusato, B.; Li, H.; Gu, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Egawa, S.; Sesterhenn, I.A.; McLeod, D.G.; Srivastava, S.; Rhim, J.S. Identification of putative stem cell markers, CD133 and CXCR4, in hTERT-immortalized primary nonmalignant and malignant tumor-derived human prostate epithelial cell lines and in prostate cancer specimens. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 3153–3161.

- Hermann, P.C.; Huber, S.L.; Herrler, T.; Aicher, A.; Ellwart, J.W.; Guba, M.; Bruns, C.J.; Heeschen, C. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 313–323.

- Wright, M.H.; Calcagno, A.M.; Salcido, C.D.; Carlson, M.D.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Varticovski, L. Brca1 breast tumors contain distinct CD44+/CD24- and CD133+ cells with cancer stem cell characteristics. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10, R10.

- Meyer, M.J.; Fleming, J.M.; Lin, A.F.; Hussnain, S.A.; Ginsburg, E.; Vonderhaar, B.K. CD44posCD49fhiCD133/2hi defines xenograft-initiating cells in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 4624–4633.

- O’Brien, C.A.; Pollett, A.; Gallinger, S.; Dick, J.E. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature 2007, 445, 106–110.

- Ricci-Vitiani, L.; Lombardi, D.G.; Pilozzi, E.; Biffoni, M.; Todaro, M.; Peschle, C.; De Maria, R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature 2007, 445, 111–115.

- Haraguchi, N.; Ishii, H.; Mimori, K.; Ohta, K.; Uemura, M.; Nishimura, J.; Hata, T.; Takemasa, I.; Mizushima, T.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. CD49f-positive cell population efficiently enriches colon cancer-initiating cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 425–430.

- Nakanishi, T.; Chumsri, S.; Khakpour, N.; Brodie, A.H.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Hamburger, A.W.; Ross, D.D.; Burger, A.M. Side-population cells in luminal-type breast cancer have tumour-initiating cell properties, and are regulated by HER2 expression and signalling. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 815–826.

- Morel, A.P.; Lievre, M.; Thomas, C.; Hinkal, G.; Ansieau, S.; Puisieux, A. Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2888.

- Fukaya, R.; Ohta, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Fujii, H.; Kawakami, Y.; Kawase, T.; Toda, M. Isolation of cancer stem-like cells from a side population of a human glioblastoma cell line, SK-MG-1. Cancer Lett. 2010, 291, 150–157.

- Shi, Y.; Fu, X.; Hua, Y.; Han, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. The side population in human lung cancer cell line NCI-H460 is enriched in stem-like cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33358.

- Boiko, A.D.; Razorenova, O.V.; van de Rijn, M.; Swetter, S.M.; Johnson, D.L.; Ly, D.P.; Butler, P.D.; Yang, G.P.; Joshua, B.; Kaplan, M.J.; et al. Human melanoma-initiating cells express neural crest nerve growth factor receptor CD271. Nature 2010, 466, 133–137.

- Luo, Y.; Ellis, L.Z.; Dallaglio, K.; Takeda, M.; Robinson, W.A.; Robinson, S.E.; Liu, W.; Lewis, K.D.; McCarter, M.D.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Side population cells from human melanoma tumors reveal diverse mechanisms for chemoresistance. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 2440–2450.

- Yang, M.; Yan, M.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Luo, Z. Side population cells isolated from human osteosarcoma are enriched with tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102, 1774–1781.

- Yao, J.; Cai, H.H.; Wei, J.S.; An, Y.; Ji, Z.L.; Lu, Z.P.; Wu, J.L.; Chen, P.; Jiang, K.R.; Dai, C.C.; et al. Side population in the pancreatic cancer cell lines SW1990 and CFPAC-1 is enriched with cancer stem-like cells. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 23, 1375–1382.

- Patrawala, L.; Calhoun, T.; Schneider-Broussard, R.; Zhou, J.; Claypool, K.; Tang, D.G. Side population is enriched in tumorigenic, stem-like cancer cells, whereas ABCG2+ and ABCG2− cancer cells are similarly tumorigenic. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6207–6219.

- Ho, M.M.; Ng, A.V.; Lam, S.; Hung, J.Y. Side population in human lung cancer cell lines and tumors is enriched with stem-like cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4827–4833.

- Baeten, J.T.; Waarts, M.R.; Pruitt, M.M.; Chan, W.C.; Andrade, J.; de Jong, J.L.O. The side population enriches for leukemia-propagating cell activity and Wnt pathway expression in zebrafish acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1388–1395.

- Xie, T.; Mo, L.; Li, L.; Mao, N.; Li, D.; Liu, D.; Zuo, C.; Huang, D.; Pan, Q.; Yang, L.; et al. Identification of side population cells in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell line and elucidation of the underlying roles in lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 4900–4906.

- Mani, S.A.; Guo, W.; Liao, M.J.; Eaton, E.N.; Ayyanan, A.; Zhou, A.Y.; Brooks, M.; Reinhard, F.; Zhang, C.C.; Shipitsin, M.; et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 2008, 133, 704–715.

- De Craene, B.; Berx, G. Regulatory networks defining EMT during cancer initiation and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 97–110.

- Lambert, A.W.; Weinberg, R.A. Linking EMT programmes to normal and neoplastic epithelial stem cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 325–338.

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1420–1428.

- Ksiazkiewicz, M.; Markiewicz, A.; Zaczek, A.J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: A hallmark in metastasis formation linking circulating tumor cells and cancer stem cells. Pathobiology 2012, 79, 195–208.

- Nieto, M.A.; Huang, R.Y.; Jackson, R.A.; Thiery, J.P. Emt: 2016. Cell 2016, 166, 21–45.

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196.

- Jolly, M.K.; Boareto, M.; Huang, B.; Jia, D.; Lu, M.; Ben-Jacob, E.; Onuchic, J.N.; Levine, H. Implications of the Hybrid Epithelial/Mesenchymal Phenotype in Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 155.

- Grosse-Wilde, A.; Fouquier d’Herouel, A.; McIntosh, E.; Ertaylan, G.; Skupin, A.; Kuestner, R.E.; del Sol, A.; Walters, K.A.; Huang, S. Stemness of the hybrid Epithelial/Mesenchymal State in Breast Cancer and Its Association with Poor Survival. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126522.

- Jolly, M.K.; Tripathi, S.C.; Jia, D.; Mooney, S.M.; Celiktas, M.; Hanash, S.M.; Mani, S.A.; Pienta, K.J.; Ben-Jacob, E.; Levine, H. Stability of the hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27067–27084.

- Elenbaas, B.; Spirio, L.; Koerner, F.; Fleming, M.D.; Zimonjic, D.B.; Donaher, J.L.; Popescu, N.C.; Hahn, W.C.; Weinberg, R.A. Human breast cancer cells generated by oncogenic transformation of primary mammary epithelial cells. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 50–65.

- Liu, S.; Cong, Y.; Wang, D.; Sun, Y.; Deng, L.; Liu, Y.; Martin-Trevino, R.; Shang, L.; McDermott, S.P.; Landis, M.D.; et al. Breast cancer stem cells transition between epithelial and mesenchymal states reflective of their normal counterparts. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 2, 78–91.

- Strauss, R.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Beyer, I.; Persson, J.; Sova, P.; Moller, T.; Pesonen, S.; Hemminki, A.; Hamerlik, P.; et al. Analysis of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in ovarian cancer reveals phenotypic heterogeneity and plasticity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16186.

- Kroger, C.; Afeyan, A.; Mraz, J.; Eaton, E.N.; Reinhardt, F.; Khodor, Y.L.; Thiru, P.; Bierie, B.; Ye, X.; Burge, C.B.; et al. Acquisition of a hybrid E/M state is essential for tumorigenicity of basal breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7353–7362.

- Bierie, B.; Pierce, S.E.; Kroeger, C.; Stover, D.G.; Pattabiraman, D.R.; Thiru, P.; Liu Donaher, J.; Reinhardt, F.; Chaffer, C.L.; Keckesova, Z.; et al. Integrin-beta4 identifies cancer stem cell-enriched populations of partially mesenchymal carcinoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2337–E2346.

- Quintana, E.; Shackleton, M.; Sabel, M.S.; Fullen, D.R.; Johnson, T.M.; Morrison, S.J. Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature 2008, 456, 593–598.

- Beck, B.; Blanpain, C. Unravelling cancer stem cell potential. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 727–738.

- Driessens, G.; Beck, B.; Caauwe, A.; Simons, B.D.; Blanpain, C. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature 2012, 488, 527–530.

- Schepers, A.G.; Snippert, H.J.; Stange, D.E.; van den Born, M.; van Es, J.H.; van de Wetering, M.; Clevers, H. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science 2012, 337, 730–735.

- He, X.; Li, B.; Shao, Y.; Zhao, N.; Hsu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. Cell fusion between gastric epithelial cells and mesenchymal stem cells results in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and malignant transformation. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 24.

- Merle, C.; Lagarde, P.; Lartigue, L.; Chibon, F. Acquisition of cancer stem cell capacities after spontaneous cell fusion. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 241.

- Ramakrishnan, M.; Mathur, S.R.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Fusion derived epithelial cancer cells express hematopoietic markers and contribute to stem cell and migratory phenotype in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 5360–5370.

- Uygur, B.; Leikina, E.; Melikov, K.; Villasmil, R.; Verma, S.K.; Vary, C.P.H.; Chernomordik, L.V. Interactions with Muscle Cells Boost Fusion, Stemness, and Drug Resistance of Prostate Cancer Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 806–820.

- Zeng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Park, S.C.; Eun, J.R.; Nguyen, N.T.; Tschudy-Seney, B.; Jung, Y.J.; Theise, N.D.; Zern, M.A.; Duan, Y. CD34 Liver Cancer Stem Cells Were Formed by Fusion of Hepatobiliary Stem/Progenitor Cells with Hematopoietic Precursor-Derived Myeloid Intermediates. Stem Cells Dev. 2015, 24, 2467–2478.

- Bjerkvig, R.; Tysnes, B.B.; Aboody, K.S.; Najbauer, J.; Terzis, A.J. Opinion: The origin of the cancer stem cell: Current controversies and new insights. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 899–904.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

698

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No